The politics of Vietnam was born in the early Cold War when Republicans made a concerted effort to undercut the national security advantage that Democrats had enjoyed since a decisive US victory in World War II. The years after the war are often remembered as a period when politics stopped at the water’s edge. Nothing could be further from the truth. Although there were a number of factors that moved the United States military deep into the jungles of Vietnam, including a “domino theory” positing that if one country fell to communism everything around it would follow, partisan politics was a driving force behind this disastrous strategy. The same political logic and prowess that led President Lyndon Johnson to strengthen the legislative coalition behind his Great Society simultaneously pushed him into a hawkish posture in Southeast Asia.

Politics at the Water’s Edge in the Early Cold War, 1946–1952

The contentious partisan debates that unfolded between 1946 and 1952 profoundly shaped the way that Representative and then Senator Lyndon Johnson and an entire generation of Democrats came to think about national security, a way that constricted the political space they felt to challenge a hawkish agenda overseas. Coming out of the victory against Germany, Italy, and Japan, the Democrats and Republicans grew deeply divided in the public arena about their relative strength in handling the issue of war and peace. During the 1946 midterm elections, Republicans were increasingly comfortable criticizing the direction of foreign policy under Franklin D. Roosevelt and his successor Harry Truman. Senator Robert Taft, Sr. (R-Ohio), who harbored great doubts about the expansion of the national security state, sounded pretty comfortable as a hawk when he said that Democrats had “pursued a policy of appeasing Russia, a policy which has sacrificed throughout Eastern Europe and Asia the freedom of many nations and millions of people.”Footnote 1 When Republicans won control of the House and the Senate for the first time since 1932, the attacks on national security were seen as part of the winning mix.

The new Republican chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Michigan’s Arthur Vandenberg, emerged as a model for bipartisanship despite the bitter feelings from the elections. In 1947 and 1948, when Republicans controlled Congress, Vandenberg worked closely with Harry Truman’s Democratic administration to create the infrastructure of the Cold War state. Indeed, the notion that politics should stop at the water’s edge grew out of the historic relationship between these two men. But the relationship between Vandenberg and Truman was more of an exception than the norm.Footnote 2

The other side of national security politics in the early Cold War revolved around fierce partisan conflict. Most Republicans realized that they were in a difficult position politically. Franklin Roosevelt and the Democrats had built a robust political coalition around domestic programs such as Social Security and the Wagner Act. Many Republicans had been on the wrong side of history during World War II, with FDR championing the US need to intervene overseas to prevent the spread of fascism. The outcome of the war had been decisive, at least with regard to fascism. Then Republicans faced the problem that there remained many colleagues, including Senator Taft, who, outside the midterm elections, were still critics of excessive intervention overseas and who warned of creating a “Garrison State.”Footnote 3 For more and more Republicans the answer was to give greater weight to the hawkish elements in their party and to take on the Democrats by focusing on the expansion of communism. The template of the 1946 elections seemed appealing.

Though Democrats retook control of Congress in the 1948 elections, the year Johnson won a seat in the upper chamber, a pivotal moment in the partisan battles took place one year later when the Chinese Communist Party took power. Republicans in Congress blasted the Truman administration for having “lost China” to the communists. They argued that Secretary of State Dean Acheson and President Truman had failed to provide sufficient support to the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek. As a result, there were now two major communist powers. Democrats were shaken by the outcome, unclear about how they should respond. In 1950, California Republican senator William Knowland pounded away at the theme. He delivered 115 floor speeches about China. Knowland said that Truman’s policies had “accelerated the spread of communism in Asia” and the “gains for communism there have far more than offset the losses suffered by communism in Europe.” The senator argued that the “debacle solely and exclusively rests upon the administration which initiated and tolerated it.” Charging Truman and Secretary Acheson with “appeasement,” he told the public that the two of them were guilty of “aiding, abetting and giving support to the spread of communism in Asia.”Footnote 4

Republicans coupled the criticism about “who lost China?” with incessant attacks on Democrats for failing to take seriously the threat of communist spies within the United States. Nobody had been better at these attacks than Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy, a fiery Republican who unleashed blistering attacks on Democrats, jumbling and making up facts, which the media repeated in their effort to remain objective. While most Senate Republicans distanced themselves from McCarthy in public, they were more than willing to let him continue with his attacks on Democrats, and they echoed his broader arguments albeit in a somewhat more restrained fashion.

As Republicans ramped up their attacks on the Democrats, the Truman administration sent the nation’s military forces in 1950, without a declaration of war, into Korea. Truman dispatched troops to provide support to the South Koreans in their effort to push back against the North Korean troops who had crossed the 38th parallel. The war, though drawing initial enthusiastic public support for a hawkish Truman, quickly turned into a political problem for his party. But the midterm elections fostered division over the issue. In July, Senator Taft wrote to a friend that “the only way we can beat the Democrats is to go after their mistakes … There is no alternative except to support the war, but certainly we can point out that it has resulted from a bungling of the Democratic administration.” During the campaign, congressional Republicans followed through on Taft’s advice and became critical of how the president was handling the war. One Republican said: “We’ll man the pumps and unroll the hose, but damned if we’ll sing, ‘Hail to the Fire Chief.’”Footnote 5 The criticism merged with the McCarthyite arguments about the number of communist spies that existed within the US government. While the Democrats retained control of Congress, Republicans gained twenty-eight seats in the House and five Senate seats. The conservative coalition of Southern Democrats and Republicans increased significantly in size. Johnson initially hesitated when asked about running to become the Senate Democratic Whip. “You’ll destroy me, because I can’t afford to be identified with the Democratic Party right now.”Footnote 6 He ran anyway and won.

The war in Korea dragged on. Truman kept expanding the size of the military commitment, yet the war between the South and North seemed to become more bogged down every month. By early 1952, there appeared no hope for a decisive victory in the region. US troops remained tied down, with thousands of troops dead or injured, while it did not look as if communists would be falling any time soon. Thousands of Americans waited for their family members to come home. Meanwhile, in Vietnam, the Việt Minh were holding their ground against the French.

These politically charged years culminated with the presidential and congressional elections of 1952. “It is true that in Europe we have never reversed the appeasement policy of Yalta and Potsdam that was approved by Mr. Truman,” said Senator Taft. “No, Mr. Truman has not stopped the advance of Communism all over the globe.”Footnote 7 Sensing that he had little chance to win reelection, Truman, whose approval ratings had fallen to a stunning 23 percent, decided that he would not run.

Republicans took a different approach in 1952, one that highlighted their national security theme. The party nominated the World War II hero Dwight Eisenhower, who identified as a Republican for the first time and ran a campaign that revolved around the Democratic failures on national security. His running mate, California senator Richard Nixon, served as an attack dog and reiterated these themes in the kind of rhetoric that was not fit for the major nominee. Nixon accused the Democrats of having “lost 600,000,000 people to the Communists” and allowing them to “honeycomb our secret agencies with treachery.”Footnote 8 Nixon had cut his teeth in the new conservative national security politics of the post–World War II period and played his role to perfection. Eisenhower did not get quite so ugly in his attacks, though he did make clear his agreement. During his most famous speech on the subject on October 25, 1952, he said, “It has been a sign – a warning sign – of the way the Administration has conducted our world affairs. It has been a measure – a damning measure – of the quality of leadership we have given.” The reason for the Korean War was simple, he said, dismissing claims it was “inevitable.” “We failed to read and to outwit the totalitarian mind.” Eisenhower famously promised that “I shall go to Korea,” with the implicit meaning that as a soldier he would be able to end the war.Footnote 9

Republicans enjoyed a major electoral success, one that a young Lyndon Johnson would never forget. Eisenhower won with 442 electoral votes and 55.1 percent of the popular vote while Republicans once again retook control of the House and Senate, proving that the outcome in 1946 had not been a total fluke. New York governor Thomas Dewey, who in 1948 had run mimicking Harry Truman’s hardline anticommunist stance, now said, “Whenever anybody mentions the words Truman and Democrat to you, for the rest of your lives remember that those words are synonymous with Americans dying, thousands of miles from home, because they did not have the ammunition to defend themselves … Remember that the words Truman and Democrat mean diplomatic failure, military failure, death and tragedy.”Footnote 10

For Democrats like Johnson, the election of 1952 had been devastating. He and his colleagues were taken aback by how strong the forces of conservatism had proven to be in the electorate and how the Republicans, who had been marginalized as isolationists in the early 1940s, now found a way to use national security as a partisan cudgel. The political battles that culminated with Eisenhower’s election and a Republican Congress proved to him just how far national security could be used to undercut Democrats and open the door for Republican success at the ballot box. Johnson, who like others in the South had a naturally hawkish disposition and was inclined to support the use of force to contain communism, came to believe that his party needed to maintain a hawkish stance or Republicans would tear them apart in elections.

Fearing Looking “Weak” on Defense, 1961–1964

The political dynamics of the early Cold War period continued to shape Johnson’s outlook for decades to come, as well as that of other Democrats he worked with. As president, John F. Kennedy constantly considered the threat that he faced from the Republican right on these sorts of issues. As he tried to navigate through difficult military problems like the US presence in Vietnam he often came back to the kinds of domestic political pressures he faced to avoid, especially as a Northern Democrat, seeming to be too liberal on Vietnam. Though Kennedy did demonstrate more predilections to push back against some of these rightwing forces with his emphasis on diplomacy and military restraint, it remains unclear what he would have done with Vietnam. The forces of conservatism remained strong, as did the domino theory, in the highest levels of international policymaking. The problem was not just Republicans but Southern Democrats, still the base of the party, who tended to be extremely hawkish on foreign policy. Democratic senators such as Richard Russell of Georgia could be counted to be some of the most rightward-leaning voices when it came to questions of war.

Vice President Lyndon Johnson became president as a result of Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963, in the city of Dallas, Texas, where conservative activists had lined the streets with signs railing against the president’s weak national security positions. LBJ was immediately cognizant of the risks that national security posed to his domestic agenda in the coming years. From his very first day in office, Johnson displayed massive ambitions about what he would do on the domestic front. He intended to extend the New Deal into new areas such as race relations and urban poverty, while solidifying an electoral coalition composed of labor, farmers, African Americans, poor Americans, liberal intellectuals, and urban Democratic machines who all retained a deep commitment to the federal government.Footnote 11 But to do so, Johnson believed, he needed to protect his flank on national security. He remembered what had happened to his party in 1952 and was determined not to let it happen again. This line of thinking guided how he approached the politics of Vietnam.

Early in Johnson’s presidency, Vietnam was not a very prominent issue outside the White House. Polls showed that only a small number of Americans knew about the war taking place in the region and even that Kennedy had increased the number of military advisors helping the South Vietnamese.Footnote 12 Two-thirds of the population reported that they were not paying attention to the situation there.Footnote 13 Florida Democrat George Smathers, one of Johnson’s closest friends and advisors, reported that he was having trouble finding any legislators who believed that “we ought to fight a war in that area of the world.”Footnote 14

Understanding that support or interest for military intervention remained shaky within his own party, Johnson nonetheless realized that Vietnam had the potential to become a major operation that would consume his presidency. He had seen this at first hand with Truman and Korea. What caused him even greater concern was that many of his colleagues, including the hawks, warned that this could, and probably would, be a losing war. Senator Russell, a Southern hawk, outlined the many reasons why the war would likely be disastrous and unwinnable. Referring to the conflict as the “Vietnam thing,” Russell called the situation the “damn worst mess I ever saw.” He warned the president that the more the United States tried to do, the “less they are willing to do for themselves,” speaking of the South Vietnamese government. Russell said that if it was up to him, and he had the option of getting out or fighting, “I’d get out.” Russell said that the territory was not worth a “damn bit,” and he feared that Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara did not understand the “history or background” of the people in the region. Russell felt that Senator Wayne Morse (D-Oregon), a top opponent of the war, reflected public opinion.Footnote 15

Johnson understood all of these concerns but did not really know how he could get out. Military risks were one factor behind his concerns, but so too were political considerations. In a subsequent telephone conversation, Johnson said to Russell that voters in places like Georgia would “forgive you for everything except being weak,” especially as Republicans raised hell about this issue. He needed to stand firm. He believed that, as soon as the public did start paying attention to the war, “The Republicans are going to make a political issue out of it, every one of them.” “I’m not going to lose Vietnam,” Johnson told Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., his Republican ambassador to Vietnam, “I am not going to be the president who saw Southeast Asia go the way that China went.”Footnote 16

During the 1964 reelection campaign, Johnson faced off against Arizona Republican Barry Goldwater, a rightwing conservative who had entered the Senate in 1952 and had picked up on the national security themes that had loomed large since then. Goldwater attacked Johnson for being both too weak and too strong. When he was on the campaign trail, Goldwater spent much of the summer months warning that Johnson was weak when fighting against communism in Eastern Europe and Asia. At the same time, he warned that the president would involve US forces in the wrong kinds of wars without the willingness to do whatever it took to achieve victory. Goldwater claimed that Johnson was planning to vastly escalate the ground war in Vietnam if he was reelected, despite all his claims to be the peace candidate. At the same time, Goldwater argued, the president was scared to use the air power and bombing arsenal that the United States had available in the brutal way that would actually be necessary to defeat the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong. Goldwater’s speeches in July 1964 centered on these themes. He warned that Johnson would go to war “recklessly” and called Vietnam “Johnson’s War.” In his acceptance speech in July at the Republican convention in San Francisco, Goldwater said that “failures infest the jungle of Vietnam.” Other Republicans agreed. Everett Dirksen of Illinois and Charles Halleck of Indiana had said earlier in the month that “Johnson’s indecision” on the war had made it a campaign issue. Halleck said that Johnson’s “lack of definite, vigorous policy” left the nation in limbo, while Senator Bourke Hickenlooper (R-Iowa) warned that “It is not time for equivocation and vacillation.”Footnote 17

Johnson took the threat from Goldwater seriously even if many Democrats and political pundits dismissed the notion that the far-right Arizonian could ever pose a credible threat. Johnson was the kind of politician who never took anything lightly. He believed in assuming the worst possible outcome and conducting the kind of campaign that devastated his opponent. Johnson, who feared that many Americans did not believe his presidency was legitimate given how he had come into office, wanted a convincing landslide victory that would create the perception of a mandate.

Johnson went after Goldwater on national security in two different and contradictory directions. The first was to demonstrate to voters that he was tough on defense. Just a few weeks before the Democratic convention in Atlantic City, NJ, Johnson had sent US Navy ships into the Gulf of Tonkin to ramp up their operations and try to intimidate the North Vietnamese. When there were reports of an attack on US ships on August 2, Johnson decided to downplay the incident and rejected any kind of military response. Although he backed away from military action, Johnson told McNamara that they needed to be “firm as hell” without making any dangerous statements that could provoke a war. Johnson explained that he had spoken with a friend, a banker on Wall Street as well as a friend of Texas, who warned that he needed to be “damned sure I don’t pull ’em out and run, and they want to be damned sure that we’re firm. That’s what all the country wants because Goldwater’s raising so much hell about how he’s gonna blow ’em off the moon, and they say that we oughtn’t to do anything that the national interest doesn’t require. But we sure oughta always leave the impression that if you shoot at us, you’re going to get hit.”Footnote 18

When McNamara reported that there might have been another attack in the early hours of August 4, though the evidence remained shaky at best, Johnson decided to be tough. During a discussion with advisor Kenneth O’Donnell, a Kennedy holdover, he and Johnson concurred that the administration was being “tested” and that they had to show they were willing to use force. Although there was almost no evidence that the attacks had been real, Johnson used them to approach Congress to pass the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which granted him authority to use force in the region. Politics was front and center in why he wanted to obtain this power. Senator William Fulbright (D-Arkansas) made it clear to Senate Democrats, who were asking why they should grant this authority, that they needed to understand the political importance. If Johnson appeared weak, Goldwater and the Republicans would use this against the Democrats. If anyone feared that Johnson was going too far in using military force, they should just imagine what Goldwater would do. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which Johnson claimed was as broad as “grandma’s nightshirt” since it gave him so much authority, passed both houses by decisive margins.Footnote 19 There were only two opposing votes in the Senate, including Senator Morse. On August 10, just three days after Congress passed the resolution, Johnson’s spirits were lifted when pollster Lou Harris found that the number of Americans supporting him over Goldwater to handle Vietnam had gone up from 59 to 71 percent.

At the same time, Johnson simultaneously wanted to argue that handing Senator Goldwater the keys to the White House would greatly increase the chances of a nuclear war. Goldwater had made a number of controversial statements, including his openness to use low-level tactical nuclear weapons in Vietnam as a way to end the war quickly without ground troops. Johnson pounced on these kinds of statements, and the fears they stimulated, to tell Americans that Goldwater would escalate the dangers that all Americans faced.

The centerpiece of the strategy came when the campaign broadcast the “Daisy” ad on September 7, a blistering television commercial where viewers saw a girl counting the petals as she pulled them off a flower. As she got closer to ten, she stopped counting. The camera zoomed in on her eyes and viewers listened to a countdown from ten to one in an ominous official voice, which was followed by the image of a nuclear explosion that could be seen in her pupils. The spot ended with Johnson explaining to voters that “These are the stakes – to make a world in which all of God’s children can live, or to go into the dark. We must either love each other, or we must die. Vote for President Johnson on November 3. The stakes are too high for you to stay home.” The Republican National Committee asked for the commercial to be removed, calling it one of the lowest moments in political campaigns as well as a violation of the Fair Campaign Practices Code, which prohibited vilifying opponents through unfair accusations. Republican Dean Burch filed a complaint, calling on the campaign to “halt this smear attack” on the US senator.Footnote 20 The Johnson team was fine with that. They pulled the ad. But the intense media scrutiny that the spot received was better than any paid advertisement could ever deliver. Everyone in the media and politics was talking about the ad, to the dismay of Goldwater and his supporters.Footnote 21 Moreover, Johnson would continue to talk about this theme, albeit in a toned-down fashion, as he tried to foster what he called a “Republican Frontlash” of voters who would leave their party given that the person at the top of the ticket was too reckless and extreme.

Johnson won the election by huge margins, 61.1 percent of the popular vote and 486 Electoral College votes. Democrats came out with sizable margins in Congress, 295 in the House and 68 in the Senate.

Ignoring Humphrey, 1965–1967

It seemed that Johnson had decisively put down any electoral threat that he faced and could now shape the political agenda around the issues that mattered to him. His vice president, Hubert Humphrey, sent him a memo making this point. He warned the president that the war in Vietnam needed to come to an end. “In Vietnam, as in Korea,” he wrote, “the Republicans have attacked the Democrats either for failure to use our military power to ‘win’ a total victory, or alternatively for losing the country to the Communists.” Continued involvement in this battle would put his domestic agenda in peril. Most importantly, the election gave Johnson a clear playing field since the Republican right had been neutralized. Humphrey wrote that 1965 was “the first year when we can face the Vietnam problem without being preoccupied with the political repercussions from the Republican right.” Humphrey warned that if “we find ourselves leading from frustration to escalation, and end up short of a war with China but embroiled deeper in fighting with Vietnam over the next few months, political opposition will steadily mount. It will underwrite all the negativism and disillusionment which we already have about foreign policy generally.”Footnote 22

Rather than taking Humphrey’s advice, Johnson isolated him from the inner circle of advisors on foreign policy. “We don’t need all these memos!” Johnson wrote the vice president.Footnote 23 Johnson still believed that communism had to be contained and that a hawkish approach to North Vietnam was in the best interests of the nation. Politically, standing firm also made the most sense so that weakness on national security would not become a problem for his administration. A liberal Democrat could survive only by being tough on defense. Johnson formed a bipartisan coalition with Senator Everett Dirksen who ensured that the Republicans would support his policy of escalation.

Johnson was savvy enough to understand the limits of presidential power. He assumed that he only had a short window for legislating. He recalled that Congress got the best out of most presidents, and they would do the same with him. The 1966 midterms would certainly see a resurgence of power for the conservative coalition that ruled Capitol Hill, and they would clearly include national security issues in their campaign. The party of the president almost always lost seats in midterm elections. Given the landslide victory he had enjoyed, the losses would probably be more severe than usual, as FDR had experienced in 1938 and Eisenhower in 1958. With this political calculation in mind, as the pressure to escalate in Vietnam increased in the mid-1960s, Johnson did not resist calls for more militarism.

Johnson pushed back against critics in his administration such as Humphrey and ignored the growing antiwar movement that was taking form on college campuses. Instead, in the spring of 1965, he accelerated the war by launching a massive bombing campaign against North Vietnam and deploying ground troops to South Vietnam. None of these decisions meant that his doubts about the war had gone away. “If we let Communist aggression succeed in taking over South Vietnam,” he later reflected, “there would follow in this country an endless national debate – a mean and destructive debate – that would shatter my presidency, kill my administration, and damage our democracy. I knew that Harry Truman and Dean Acheson [Truman’s secretary of state] had lost their effectiveness the day that the Communists took over China.”Footnote 24 Though in public he stood firm as a resolute hawk, in private he continued to share his reservations and fears with friends like Richard Russell.

The opposition to the war kept growing. Liberals started to move into open rebellion against the Democratic administration. In 1965, there were peace rallies in New York and Washington that drew an impressive 25,000 people each. In March, student members of the Students for a Democratic Society started to conduct “teach-ins” that mobilized opposition to Vietnam. An antiwar movement also took strong hold at the grass roots. Protests started to break out all over the country as younger liberals turned decisively against the Johnson administration. All of his accomplishments on the domestic front started to be overshadowed by the controversies over the war.

Some of the opposition took form in the halls of Congress. Senator William Fulbright conducted blistering hearings into the war, dragging members of the administration in front of the television cameras to ask tough questions about the justification for this war. Fred Friendly, who headed CBS News, convinced his fellow executives to cover some of the hearings on television, which would require preempting popular shows such as Captain Kangaroo. The hearings gave Americans a look at administration officials including Secretary of State Dean Rusk, former diplomat George Kennan, and former ambassador to South Vietnam General Maxwell Taylor being asked tough and hard-hitting questions about the war. When Rusk said that the “prospect for peace disappears” if the United States did not confront the communist threat, Fulbright tore apart everything that he said, arguing that Vietnam did not involve any vital US interests and could be a “trigger for world war.” Johnson came to hate Fulbright, whom he mocked privately as “Senator Halfbright.” But the hearings were damaging. As the historian Randall Woods has argued, the hearings “opened a psychological door for the great American middle class … If the administration intended to wage the war in Vietnam from the political center in America, the 1966 hearings were indeed a blow to that effort.” Advisor Joseph Califano told the president that speechwriter “Dick Goodwin called yesterday to say that everywhere he speaks, he runs into deep concern about the situation in Vietnam. He said he is personally and firmly convinced that you are pursuing the correct course, but that the Fulbright hearings particularly are doing a tremendous amount to confuse the American people.”Footnote 25 The network executives allowed Friendly to broadcast only some of the hearings and ultimately turned back to more lucrative shows.

Others on Capitol Hill, such as Idaho’s Democratic senator Frank Church, started to speak out openly against the war. He called for an immediate bombing halt. The administration’s “worst problem,” Johnson told Dirksen, was not military but the “speeches that are made about negotiation … and about pulling out … They use those, the communists take them and print them up in pamphlets and circularize them in newspapers … They keep all the government fearful.”Footnote 26 The liberal opposition was not all partisan. There were more voices in the Republican Party, such as the New York congressman Jacob Javits, who started to express similar concerns.

Yet Johnson’s fears of the right greatly overshadowed any concerns about liberals or the left who were criticizing the war. “Don’t pay any attention to what those little shits on the campuses do,” Johnson told Undersecretary of State George Ball. “The great beast is the reactionary element in the country.”Footnote 27 National Security Advisor William Bundy recalled that everyone in the administration feared that to make a “‘soft’ move” would be politically devastating. And Johnson was not making things up.Footnote 28 Even as Dirksen and the Senate Republicans backed his policies, House Republicans were extremely critical of the administration for being too timid.

As Johnson predicted, Republicans stressed national security as a major issue in the midterm campaigns. None other than Richard Nixon, seeking to revive his political image after losing the presidential election in 1960 and the California gubernatorial election two years later, stumped for Republican congressional candidates across the country. He made national security and Vietnam central themes. He criticized the administration for a policy of “retreat and defeat” in Vietnam. With college students protesting the war from the left, Nixon and other Republicans claimed that Johnson was unwilling to use enough force to bring the conflict to an end. Sounding like Goldwater in 1964, Nixon insisted that the president had to use more air power and unleash more bombs to end this ground war. This, combined with attacks on rising deficits and disorder in the cities, allowed the conservative coalition to vastly increase its numbers. Republicans gained forty-seven seats in the House.

When Johnson analyzed the results, he was worried about the direction his party seemed to be moving, one that was in contrast to public opinion and Congress. Polls showed that the war had been important to the Republican victories. Many of the new Republicans were more hawkish than the people they replaced. Polls consistently showed that, even though Americans were unhappy with the situation in Vietnam, they opposed withdrawal by sizable majorities and wanted more military intervention, not less. This was why conservatives like the new governor of California, Ronald Reagan, were demanding that Johnson authorize a full escalation of the war. Nixon, who could not have been more pleased with the election, called it a rejection of Johnson’s policies. The election was the “sharpest rebuff of a president in a generation,” and Vietnam was the main issue. He warned “our friends and enemies abroad” that the election meant “more support, rather than less, for the principle of no reward for aggression.”Footnote 29

With the conservative coalition back in control of Congress, they started to put pressure on Johnson in 1967 to restrain domestic spending. Johnson understood from all of his economists that, to continue financing the war in Vietnam while maintaining funding for his social programs, he would have to request a tax surcharge from Congress to pay for everything. The surcharge was also essential to restraining the growing inflationary pressures that the economy was facing as a result of so much government spending. When the president sent his request to Congress in August 1967, the conservatives said no. Wilbur Mills (D-Arkansas), the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, insisted that if the president wanted his tax he would have to agree to steep cuts in social spending: he would have to choose between guns and butter.

Johnson’s advisors urged him to stand firm. They warned that the kinds of cuts that the conservatives were calling for would be disastrous to his domestic agenda. The spending reductions would cripple the programs that he already passed and prevent him from doing anything more. The possibility of achieving a Great Society would disappear.

As the White House and Congress faced off in this budgetary battle, the antiwar movement exploded all over the country, and “Johnson’s War” became the new term through which activists discussed what was going on in Vietnam. In April 1967 the civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr., rocked the White House when he publicly came out against the war. He had expressed criticism of the war in earlier settings, but always with caution and at lower-level events. This marked his formal embrace of an antiwar movement that still had lukewarm support in much of the country, including among many prominent civil rights leaders. Speaking at the historic Riverside Church in New York City, King told the 3,000 people in attendance that “my conscience leaves me no other choice” but to speak out against the war.Footnote 30 The president’s daughter, Luci Johnson, remembers that the last words she would hear before going to bed every night were: “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” The student protestors on Pennsylvania Avenue, standing near the walls of her bedroom, made their message loud and clear. She and her sister woke up to the same chants.Footnote 31

One of the reasons that the war took on such urgency was that the nation had a peacetime draft in place, which meant that millions of Americans had friends or family members who felt the impact of the war. Even in middle-class families where college education protected many younger members from going to war because of exemptions and deferments, the threat remained very real and they knew others who were not so fortunate. The movement took to the streets and commanded immense attention within the media, bringing daily coverage to the problems of Vietnam. In late October 1967, the antiwar movement staged one of the most important weeks up to then with “Stop the Draft Week.” Thousands of demonstrators all over the country turned in their draft cards or burned them. At the University of Wisconsin, demonstrators confronted Dow Chemical Company that was there to recruit students. The company notoriously made napalm, the gasoline-based gel used to defoliate the jungles of Vietnam. Tens of thousands of younger Americans flooded into Washington, DC, and marched on the Pentagon.

Administration officials were struggling to maintain their confidence as they watched the protests on their television screens and read about them on the front pages of newspapers. Many had children who were directly or indirectly involved in the protests, bringing the criticism right to their home. They went to work in the White House or Pentagon, only to come home and find antiwar material plastered all over their children’s walls and pacifist music of the counterculture blaring from their stereos.

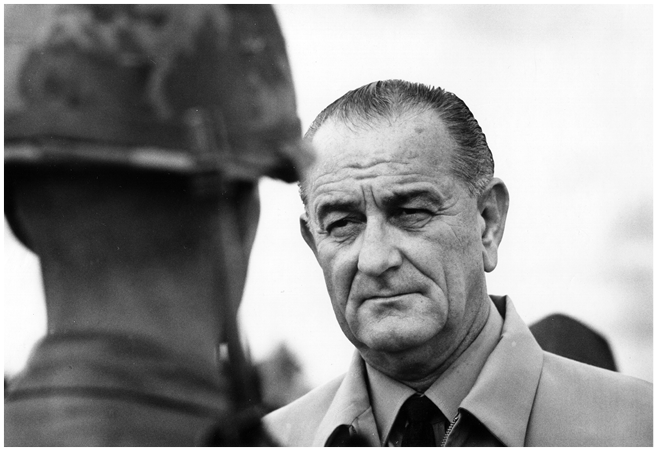

Figure 15.1 President Lyndon B. Johnson inspects a marine at Cam Ranh Bay Air Force Base (October 26, 1966).

The news media had also become more critical of the administration’s Vietnam policies. It took the press a long time to start broadcasting and publishing negative coverage of the war. During the first few years, most reporters relied on military officials for their information. Their accounts were still generally supportive of the policy. Starting in late 1966, that slowly started to change. Writing for the New York Times (starting with a story in late December), Harrison Salisbury was the first reporter to actually go to North Vietnam and start producing reports of what he was seeing, unfiltered by the military officials. His emphasis was on the civilian damage being caused by American force. Others followed him in 1967. Reporters in print and television were bringing Americans stories from what they were seeing on the frontlines, sharing a narrative that looked very different from what Johnson was saying. The stories ranged from the failures of US military efforts to atrocities committed against civilians.Footnote 32

1968

On January 31, 1968, any remaining faith that Americans had about the war soon coming to an end disappeared. The National Liberation Front launched a surprise attack, the Tet Offensive, on the US Embassy in Saigon and other key South Vietnamese military installations. While the United States eventually did repulse the attacks, the severity of the incident left many people in the country doubting all claims coming from Johnson and General William Westmoreland that the war would soon come to an end. When Westmoreland requested 206,000 more troops for the war, the domestic conflict intensified.

CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite, one of the most respected sources of news in that generation, broke with the veneer of objectivity when he closed his show by saying: “We have been too often disappointed by the optimism of the American leaders, both in Vietnam and Washington, to have faith any longer in the silver linings they find in the darkest clouds … For it seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate … To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past … To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion. On the off chance that military and political analysts are right, in the next few months we must test the enemy’s intentions, in case this is indeed his last big gasp before negotiations.” Looking at the camera with a somber face, he said: “But it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could. This is Walter Cronkite. Good night.”Footnote 33

With the next presidential election looming, Johnson watched as his political coalition unraveled while his opponents gained momentum. The fears that he had developed about conservatives early in his career seemed to be coming true. He had underestimated just how deep the opposition to the war would become among liberals, and he seemed to have little response to the antiwar movement. A president who had been determined upon taking office not to let the politics of national security swamp his domestic agenda watched as this happened as a result of his own actions.

Going into the election the situation seemed increasingly dire. The Republican nominee would be Richard Nixon, marking how politics had come full circle since 1952. Vietnam was at the very top of Nixon’s agenda as the Republican nominee asserted that this war marked the complete failure of the Johnson administration to handle the communist threat. Nixon argued that he would bring the war to an end, though he remained vague about how he intended to do this. He alluded to his willingness to use force but also hinted that diplomacy would be on the table again. At the same time, Nixon appealed to his supporters – those he called the “Silent Majority” – as the Americans who were not causing disruptions on the street by protesting, but who still believed in the values of their country. He hoped to separate core working- and middle-class Democratic voters from their party by tying Johnson to the antiwar movement which, ironically, did not like Johnson either.

During the Democratic primaries, Johnson faced a challenge from Minnesota senator Eugene McCarthy, who ran as the antiwar candidate, framing his campaign around a rejection of involvement in Vietnam. McCarthy appealed directly to the antiwar movement and hoped that the arguments about what had gone wrong in anticommunist policy would appeal to a wide spectrum of voters. He attracted huge numbers of younger Democrats who found him to be the only reasonable voice in a party they saw as having become corrupt. McCarthy enjoyed a very strong and unexpected second-place finish in New Hampshire.

Tired and broken down, fearing that he might lose, the president decided to withdraw from the campaign. Johnson made a dramatic announcement on March 31 before a national televised audience who had been expecting to hear another standard address about the war. “With America’s sons in the fields far away,” he told a stunned audience on television, “with America’s future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world’s hopes for peace in the balance every day, I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office – the presidency of your country.”Footnote 34 He concluded by saying that he would not run for the nomination. Following the announcement, he turned his attention to diplomacy and the budget. In April, Johnson reached a deal with Congress, one his liberal advisors did not like, that included a 10 percent tax surcharge in exchange for $6 billion in cuts in discretionary domestic spending. In the parlance of the times, he cut butter to finance the guns.

But the politics of Vietnam continued to bog down the Democrats. The Democrats splintered in many directions. With McCarthy doing well, Senator Robert Kennedy of New York, who had an extraordinarily tense relationship with Johnson, neither trusting the other, entered the contest. Like McCarthy, whose supporters resented the senator for coming into the campaign only after the Minnesotan had proved how vulnerable the president was, Kennedy likewise came down hard against the war after entering the race, including the inequitable way that the draft worked by falling hardest on the most disadvantaged, though his campaign came to an abrupt end when he was assassinated in June following his victory in the California primary.

The candidate who paid the highest political price for Vietnam was Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who gained the Democratic nomination and had to run as the heir to Johnson. Once a maverick young Democrat who had shaken the party in 1948 by calling on his colleagues to embrace civil rights, Humphrey was now the face of a broken establishment. The antiwar movement refused to get on board with Humphrey’s candidacy, as became evident with protests that took place outside the convention in Chicago. Antiwar activists inside and outside the convention hall demanded a strong antiwar plank in the party platform, but they were denied. When police clashed with the protestors in front of the convention, the chaos that unfolded over the war made the Democrats look divided and weak. McCarthy was deeply disillusioned with Humphrey and would refuse to endorse him until late in October. Humphrey left Chicago with the nomination, but without robust support.

Richard Nixon, though vague on what he would actually do, kept promising that it would be very different from what the nation was seeing and hearing from Johnson. “When the strongest nation in the world can be tied up for four years in a war in Vietnam,” he said upon accepting the nomination, “with no end in sight, when the richest nation in the world can’t manage its own economy, when the nation with the greatest tradition of rule of law is plagued by unprecedented lawlessness … it’s time for new leadership for the United States of America.”Footnote 35

Humphrey struggled over how to handle the war. Fearing Johnson’s wrath and appearing to be disloyal, he resisted coming out too strongly against his own leader. In late September, with his polls suffering, Humphrey finally made a speech in which he promised to move forward with a bombing halt should he be elected to the presidency. The speech, though timid, was sufficient to convince antiwar activists that he had finally seen the light. His polls improved as more liberals finally started to come out in favor of the campaign. On October 31, just days before the election, Johnson himself went on television to announce a temporary bombing halt. The announcement boosted Humphrey’s standing in the poll once again, but it was too late.

The negotiations themselves were subject to the political battles. Johnson got word that people connected to the Nixon campaign were secretly talking to the South Vietnamese government, urging them to reject any deals that emerged on the grounds that a Nixon administration would give them much better terms for agreement. Fearing that the bombing halt would greatly boost the chances of Humphrey’s victory, the Republican activist Anna Chennault, who worked for Nixon’s national security advisor Henry Kissinger and had deep ties to the government in Saigon, had passed the message to the South Vietnamese. Kissinger had informed Nixon that Johnson was working on a deal. In exchange for the bombing halt, the Soviets were pressuring Hanoi into ending the war. According to notes that were taken by Nixon’s top aide H. R. Haldeman, the Republican candidate understood what was happening as he told his future chief of staff that their friends should keep “working on” efforts to sway the South Vietnamese and stifle the peace talks that could swing the election toward Humphrey. “Keep Anna Chennault working on” South Vietnam, his notation about Nixon’s order said; “Any other way to monkey wrench it? Anything RN can do.”Footnote 36 Johnson learned of the operation through wiretaps that he was conducting on the Republicans.

Johnson called Senator Dirksen on the telephone to complain about what Nixon was doing. “I think that we’re skirting on dangerous ground,” Johnson said to his old friend. “This is treason.” Johnson said he did not know exactly who was behind the operation, but “I know this: that they’re contacting a foreign power in the middle of a war.” When Dirksen agreed “That’s a mistake!” Johnson said, “And it’s a damn bad mistake.”Footnote 37 The president also complained to Senator Russell that the South Vietnamese did not understand how the American system worked. If Nixon was elected, liberal Democrats who were against the war would have even more influence. “They don’t realize they’ll have you and Fulbright and all the Congress that I’ve had. And they think that [if] they get Nixon they get all of Nixon’s policies. Now, they’re not going to, Nixon’s not going to be able to be much harder than I have been.”Footnote 38 In the end he decided that he would not reveal this plan since it would disclose that he had authorized surveillance on the South Vietnamese ambassador and other communications with Saigon. Johnson also feared that if Nixon won it would undermine his legacy.Footnote 39

None of this was sufficient to save Humphrey’s election, Johnson’s coalition, or liberalism in the short term. By a narrow margin, lowered in part by the third-party candidacy of the racist Alabama governor George Wallace, Nixon won the presidency. Nixon won 43.42 percent of the popular vote and 301 Electoral College votes. Humphrey gained 191 Electoral College votes and 42.72 percent of the popular vote. The Democrats retained control of both houses of Congress, with 58 seats in the Senate and 243 seats in the House. Within the new Congress, liberals were much more powerful and much more vociferous in threatening to cut funding for the war.

The politics of the war in Vietnam played out exactly in the way that Johnson had feared most. The pressure from the right remained unyielding throughout his presidency, creating a powerful force that helped keep Johnson on a hawkish track. Political fears converged with his understanding of foreign policy to lead the president, and the nation, deeper and deeper into Vietnam.

Johnson famously pitted Vietnam against the Great Society. He told his biographer, Doris Kearns Goodwin, “That bitch of a war killed the lady I really loved – the Great Society.” The war, however, was of his own making. And the same political calculations that he used on domestic issues shaped his decision to ignore critics, including his own vice president, and double down on the battle.

But the way that the war unfolded did not give Johnson much political benefit for standing firm. The Democratic Party ended his term deeply divided, while Republicans were able to rally around a candidate who set the terms for national security debate for decades to come. Nixon, who had believed since the late 1940s that attacking Democrats as weak on defense offered a winning formula for the Republicans, entered into the White House determined to bring an end to the Vietnam War while continuing to disparage the incompetence of his opposition on questions of war and peace. Though sidetracked by Watergate, the coalition that Nixon put into place would prove to be robust in the coming decades, particularly when Ronald Reagan won election to the White House in 1980. Republicans prevented major expansions of Johnson’s domestic agenda, pushed for sharp reversals in the direction of other policies – such as taxation – and gained great support for a hawkish military agenda that left Democrats constantly playing defense – that is, until Republicans in 2003 started a Vietnam War of their own in Iraq.