9.1 Introduction

Special economic zones (SEZs) are widely used around the world. They go by many different names and come in many varieties. There is no universal definition for SEZs. The terminology used across countries – free zones, free trade zones, special economic zones, export-processing zones, industrial parks, regional development zones – varies wildly. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) World Investment Report 2019 defines SEZs as geographically delimited areas within which governments facilitate industrial activity through fiscal and regulatory incentives and infrastructure support.Footnote 1 This definition centers on three key criteria: a clearly demarcated geographical area, a regulatory regime distinct from the rest of the economy, and infrastructure support. This relatively narrow definition would exclude some types of economic zones that are normally associated with SEZs. For example, common industrial parks, especially in developed economies, occupy a defined area and enjoy infrastructure support, but they do not offer incentives or a special regulatory regime. The famous maquiladoras in Mexico is another example. Individual enterprises are provided the benefits of free zones. Such a free-point regime can be considered as a form of SEZs but would not be counted as zones under this definition.

Similarly, even though investment facilitation stands increasingly high in the global economic agenda, its concept remains fluid and up for debate. UNCTAD defines investment facilitation as the set of policies and actions aimed at making it easier for investors to establish and expand their investments, as well as to conduct their day-to-day business in host countries.Footnote 2

Previous studies on SEZs have focused on documenting success stories and failures, describing key characteristics of SEZs and analyzing their economic, social, environmental, and development impacts.Footnote 3 Discussions on investment facilitation have centered around its concept, its legal and policy implication, and the possibility of an international agreement in different forums.Footnote 4 Less discussed are the nexus between SEZs and investment facilitation, and whether and how they can be combined to maximize their benefits as investment policy instruments. In addition, the global crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the necessity and urgency on policy adjustments for a sustainable recovery and future development.

This chapter aims at identifying the interconnections between SEZs and investment facilitation. With a brief overview of the development of these two policy instruments, it shows that SEZs and investment facilitation can complement each other and be mutually supportive. By discussing the challenges brought by the COVID-19 pandemic, it analyzes how SEZs and investment facilitation need to transform and how countries can be better equipped to capture opportunities in the post-pandemic world.

9.2 SEZs: Universe and Trends

SEZs have a long history. The concept of freeports dates back many centuries, with traders moving cargoes and reexporting goods with little or no interference from local authorities. Modern customs-free zones, which tend to be adjacent to seaports, airports, or border corridors and usually are fenced to demarcate a separate custom area, appeared in the 1960s. They began multiplying in the 1980s, with the spread of export-oriented industrial development strategies in many countries and the increasing reliance on offshore production. The acceleration of international production in the late 1990s and 2000s and the rapid growth of global value chains (GVCs) have witnessed the expansion of export-processing zones (EPZs) and industrial parks/zones among developing economies, aiming to emulate the early success stories. The 2008 global financial crisis and deceleration in globalization have barely slowed the trend as governments respond to the increasing competition for global mobile investment with new types of SEZs, such as science/tech parks and services parks. The World Investment Report 2019 identified some 5,400 zones across 147 economies globally, more than 1,000 of which were established since 2014, and more than 500 new SEZs were expected to open in the coming years (see Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 Historical Trend in SEZs.

SEZs are widely used yet relatively concentrated. UNCTAD data show that developing Asia alone hosts 75 percent of the aforementioned 5,400 SEZs, where over 2,000 SEZs are in China, followed by the Philippines (528), India (373), and Turkey (102). Latin America has a long history with SEZs. Some of the free trade zones there were established as early as the early nineteenth century. Currently, the region has almost 500 SEZs. Developed economies have a relatively low density of SEZs, with the exception of the United States. Over 70 percent of the zones in developed economies are in the United States, most of which are foreign trade zones. Most European countries have either no SEZs or only customs-free zones. Economies with geographical challenges and/or insufficient resources, such as Small Island Developing States and the least developed countries, also have fewer SEZs.Footnote 5

SEZs differ substantially among economies at different levels of development. Most SEZs in developed economies are customs-free zones, focusing on supporting complex cross-borders supply chains with relief from tariffs and red tape. The rationale is the preference of an overall business-friendly environment to privileged area. In developing economies, in contrast, the bulk of SEZs are multi-activities zones aiming at building, diversifying, and upgrading industries by attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). Industry-specialized zones are more common in transition economies. This staged pattern of zone development is also apparent within economies. For example, in China, zones were initially designed to attract export-oriented manufacturing along its coastal regions and later diversified toward industrial upgrading and integration.

International and regional cooperation on SEZs have been on the rise. There are various models where zones can be developed with the cooperation of a foreign partner: zones developed by foreign developers or through joint ventures with local companies as private FDI, zones developed by host country governments through public–private partnerships with foreign developers, and zones developed as government-to-government partnership projects. The majority of such SEZs are the first two types of zones. The development of government-to-government partnership zones are encouraged by a mixture of development assistance, economic cooperation, and strategic considerations. Examples include industrial parks developed by France and Germany in the State of Palestine, the Caracol Industrial Park developed by the Inter-American Development Bank and the United States Government in Haiti as a relief effort after the devastating earthquake in 2010, China’s Overseas Economic Cooperation Zone program and Japan’s “Industrial Townships” project in India.

Deepening regional integration has also accelerated the development of border and cross-border SEZs. Zones have been developed along regional economic corridors. The development of the Greater Mekong Subregion corridors, a regional economic cooperation program that involves Cambodia, China, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, Thailand, and Viet Nam, has encouraged these countries to build SEZs in border areas to better utilize the improved connectivity along the corridors.Footnote 6 In Africa, The Musina/Makhado SEZ of South Africa is strategically located along a principal north–south route into the Southern African Development Community and close to the border between South Africa and Zimbabwe. The governments of Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali launched a cross-border zone encompassing all three countries to leverage the opportunities provided by regional integration.Footnote 7 However, global experience with SEZs is mixed. There are many examples of highly successful SEZs, especially in Asia, where economies have followed the export-oriented development strategies. SEZs have played a key role in industrialization of the so-called Four Asian Dragons and have long been praised for their experimental role in boosting China’s development following its “reform and opening-up” policy.Footnote 8 But not all SEZs are successful. Many zones, across all regions of the world, have failed to achieve their supposed economic benefits, either measures in terms of investment or export growth or job creation. Zones have been criticized for being enclaves, with few linkages to local economy and few spillovers. There are concerns over labor standards and working conditions in zones, including longer working hours, laxer health and safety standards, lack of training, and lower wage levels. Negative environmental impacts such as pollution and misuse of land have also been highlighted.Footnote 9

Yet the enthusiasm for SEZs has continued as governments respond to the increasing competition for global mobile investment with more zones. Over the past decade, global FDI has been stagnant. As a result, the competition between SEZs, both within and among countries, has become more severe. There are increasing doubts over SEZs’ effectiveness as an investment policy instrument. Governments are in need of targeted policies to attract, anchor, and upgrade FDI. With this backdrop, the discussion of investment facilitation measures, which focuses on alleviating ground-level obstacles to investment, has gained momentum internationally.

9.3 Investment Facilitation: Concept and Progress Achieved

Investment facilitation is high on the global economic agenda. Since UNCTAD initiated its policy dialogue on investment facilitation in 2015, discussions are taking place in various fora and contexts. International organizations including UNCTAD, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the World Bank have conducted in-depth research. More than a hundred members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) are participating in the formal negotiation for a multilateral agreement on investment facilitation for development. The Group of 20 (G20) adopted the G20 Guiding Principles for Global Investment in 2016, emphasizing importance of transparency and coherence of investment policies. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) has developed its Investment Facilitation Action Plan, which has served as a valuable reference tool for improvement of the APEC investment climate.

By far, there is no universally agreed definition of investment facilitation. UNCTAD defines investment facilitation as “the set of policies and actions aimed at making it easier for investors to establish and expand their investments, as well as to conduct their day-to-day business in host countries.” It focuses on alleviating ground-level obstacles to investment, for example, by introducing transparency and improving the availability of information, making administrative procedures more efficient and effective, and by enhancing predictability and stability of the investment policy environment.Footnote 10 WTO members have avoided this problem by giving a broad description in the scope of the agreement in negotiation, but the WTO secretariat has summarized a very similar concept: “in the context of the WTO, investment facilitation means the setting up of a more transparent, efficient and investment-friendly business climate by making it easier for domestic and foreign investors to invest, conduct their day-to-day business and expand their existing investments.”Footnote 11

Often closely associated with investment facilitation in investment policy discussions is investment promotion. In the wider investment policy context, investment facilitation and investment promotion work hand in hand. But they are two distinct concepts. Investment promotion is about promoting a location as an investment destination (e.g., through marketing and incentives) and is therefore often country-specific and competitive in nature (see Table 9.1).

Investment promotion “Marketing a location” | Investment facilitation “Making it easier to invest and do business” |

|---|---|

|

|

The confusion between investment facilitation and investment promotion or investment retention is attributed to a few factors. First and foremost, investment promotion, facilitation, and retention are a continuum, rather than a process of clear-cut phases. Another reason for this confusion is that some policy instruments can be used for all three phases, and some activities, whether under the name of investment promotion, facilitation, or retention, lead to improved trade and investment environment and enhanced ease of doing business. In addition, almost all investment promotion agencies (IPAs) have been tasked with both investment promotion and facilitation, as well as providing aftercare services. IPAs provide facilitation services throughout the whole process of investment realization.

9.4 Investment Facilitation and Trade Facilitation

Trade facilitation is another concept that is frequently mentioned together with investment facilitation. Besides the obvious similarities in name, there are clear parallels between trade and investment facilitation. UNCTAD’s Global Action Menu for Investment Facilitation introduced ten lines of action, most of which are of a similar nature as trade facilitation measures: promoting accessibility and transparency of policies and regulations, streamlining of regulation and administrative procedures, enhancing predictability and consistency in the application of policies and designation of a focal point or single window, to name a few.Footnote 12

Differences between investment facilitation and trade facilitation are apparent. Trade facilitation is aimed at border measures applying to goods. Investment facilitation goes well beyond border issues and relates to the pre- and post-establishment of investment, involving a wide range of regulatory issues across many areas and at many levels of government. It is a horizontal policy instrument, applying to all sectors and industries.

As discussed in the previous section, the increasing pressure on governments to compete for global FDI has encouraged the adoption of various investment policies worldwide, among which investment facilitation measures account for a growing proportion. The UNCTAD Investment Policy Monitor Database shows that in 2020, about 33 percent of 135 national investment laws from 130 countries and economies refer to investment facilitation-related elements, an increase from 20 percent in 2016.Footnote 13 Nevertheless, a significant gap remains in national and international investment policy regimes. Among the 135 national investment laws analyzed, transparency of laws and regulations, a key aspect of investment facilitation, is rarely referred to in investment laws. Only 11 percent of such laws stipulate that governments will make laws and regulations pertaining to investment publicly available (see Figure 9.2). The number of investment facilitation measures adopted by countries over the past four years remains relatively low compared with the numbers of other investment promotion measures. UNCTAD’s Investment Policy Hub shows that from 2016 to 2019, countries adopted almost 500 investment policy measures, among which 72 related to investment facilitation (less than 15 percent). Concrete investment facilitation provisions are still absent from the majority of some 3,300 existing international investment agreements (IIAs).

Figure 9.2 Presence of (or references to) key investment facilitation concepts (percent share in 135 national investment laws analyzed).

9.5 Combining SEZs and Investment Facilitation

SEZs and investment facilitation have a number of important distinctions and areas of divergence. SEZs are a part of industrial policy. Their purpose is much wider than investment facilitation, encompassing industrial development and economic diversification objectives. SEZs are competitive in nature. Many SEZs target cost-conscious investors in labor-intensive export-oriented industries, leading to highly competitive export promotion practices. In contrast, investment facilitation measures are generally applied horizontally. They are not investor targeting and are noncompetitive. SEZs tilt the playing field between firms inside and outside zones – the opposite of what investment facilitation aims to achieve. SEZs in many countries have been found to have relatively limited beneficial spillover effects to domestic firms outside the zones, while investment facilitation, despite having its origin in efforts to promote foreign investment, is equally beneficial for domestic investors. When acting as investment policy tools, SEZs and investment facilitation are usually taken as two distinct sets of investment policy. UNCTAD data show that from 2010 to 2019, SEZ programs and investment facilitation measures accounted for 21 and 30 percent of national policy measures, respectively, indicating the increasing importance of investment facilitation in national investment policy tool kit (see Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3 National policy measures related to investment promotion and facilitation, 2010–2019 (percent).

SEZs are often questioned over their possible distortion of competition as they provide preferential treatment to specific regions or sectors. They have been seen as a second-best solution compared with policies aiming at creating an investor-friendly environment in the wider economy. This explains the relatively low SEZ density in most developed countries as the business environment in these countries is considered sufficiently attractive. In contrast, developed countries adopt more investment facilitation measures than developing countries. The earlier version of the Investment Facilitation Index, which maps the adoption of investment facilitation measures at country level in eighty-six WTO members, shows that developing countries in general have fewer facilitation measures in place than developed countries. Among the top twenty WTO members in the Investment Facilitation Index ranking, sixteen are in the high-income group and four members are in the upper-middle-income group, namely, China, Mexico, Costa Rica, and Turkey.Footnote 14

SEZs and investment facilitation are also closely linked. They share a common purpose: to attract investment in order to create jobs, generate exports, and boost growth. They share a common tool kit: streamlined rules, regulations, and administrative procedures and other measures to create a stable and predictable climate for business. They are also mutually supportive: Investment facilitation measures are a fundamental part of the value proposition of SEZs, and SEZs often serve as a sandbox for such measures.

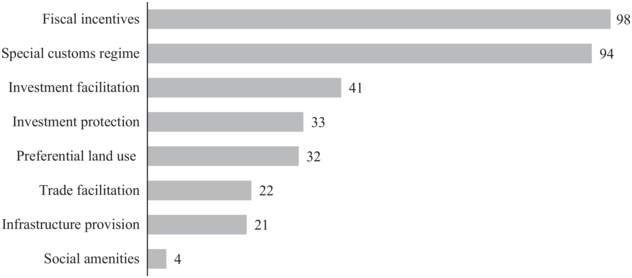

Investment facilitation has been an important investment attraction tool in SEZ laws. Approximately one-third of the SEZ laws include rules on investment facilitation (see Figure 9.4). One frequently used tool is the streamlining of registration procedures, for instance, by providing a list of documents required for admission or by setting deadlines for the completion of approval procedures. Some SEZ laws require zone operators to establish a single point of contact or a one-stop shop to deliver government services to businesses within SEZs (e.g., the Philippines, Special Economic Zone Act). Other laws provide for the creation of business incubators in zones to assist enterprises in their initial periods of operation by offering technical services and to ensure the availability of physical workspace (e.g., Kosovo, Law on Economic Zones). Some laws also eliminate restrictions on recruitment and employment of foreign personnel within the zones (e.g., Nigeria, Export Processing Zones Act).

Figure 9.4 Investment attraction tools in SEZ laws (number of laws, ![]() ).

).

Investment facilitation measures in SEZs add a winning edge to zones. In general, the value proposition of SEZs – the package of advantages that zones provide – is an important factor when investors make an investment decision. Along with incentives, locational advantages, infrastructure, services, and facilitation of administrative procedures are crucial elements in SEZs’ value proposition. Zone policymakers, developers, and IPAs have relied heavily on generous incentives to attract investors. However, recent analyses find no correlation between fiscal incentives offered to investors and zone growth in terms of jobs and exports.Footnote 15 This may partly be caused by the increasing convergence of zone investment incentives and the lack of differentiation. Researchers have also found that failed zone programs, such as in India, have generally been negatively affected by excessive bureaucracy.Footnote 16 To win the competition for global mobile investment, zone policymakers need to address specific concerns of potential investors and create an appealing business environment, where investment facilitation measures aiming at easing cumbersome administrative procedures and red tape are at the core of such an environment. An attractive business environment is the key to the success of an SEZ, and investment facilitation measures are at the core of such an environment.

The rationale for providing investment facilitation measures in SEZs but not the whole economy is similar to the rationale of establishing SEZs in most developing countries. First, there is the relative ease of implementing reforms through SEZs. In countries where governance is relatively weak and where the implementation of reforms nationwide is difficult, SEZs are often seen as the only feasible option or as a first step.Footnote 17 As enclaves of differential regulation, SEZs can reduce the pressure for governments to pursue difficult nationwide structural reforms. Early adopters of SEZ programs in Asia have deliberately used zones to introduce national reforms gradually in a dual-track approach that slowly exposed the rest of the economy. Even though investment facilitation measures are generally not as controversial as investment liberalization, the implementation of such measures may still meet resistance from current players. For example, introducing a fast-licensing process for certain category of investors planning to open business in SEZs would meet far less objection than enacting new national legislation to reduce the bureaucracy surrounding procedures for the admission of foreign investments.

Second, the perceived low cost of implementation. A key rationale for SEZs is their low cost in relative terms compared with that of building equivalent industrial infrastructure in the entire economy. Capital expenditures for the development of an SEZ – especially basic zones offering plots of land rather than hypermodern “plug-and-play” zones – are often limited to basic infrastructure connections to the zone perimeter. With SEZs, developing countries are able to ease the infrastructure challenges in the country and to concentrate public investment in infrastructure, such as reliable utilities, telecommunication, and water and waste management installations, in a limited geographical area. Facilitation of administrative procedures for business and investors in SEZs follows the same thinking. Take providing one-stop shop/single window for foreign investors as an example. As simple as it may sound, it requires a well-structured investment regime, effective interagency collaboration and coordination, thorough investment process analysis, data harmonization and documents simplification, as well as technical capacity in terms of IT infrastructure with necessary financial support. Nationwide implementation takes efforts not only at the central government level but also support from local governments at regional and subregional levels. Building a small-scale sector-specific single window in SEZs to serve investors in zones only is more practical and requires less inputs.

The role of investment facilitation measures in SEZs is increasingly valued by zone policymakers and investors. Less recognized is the role of SEZs for investment facilitation measures. SEZs are in a unique position to develop and implement investment facilitation measures. The role of SEZs in promoting investment facilitation can be seen in a number of ways. First, SEZs can be experimental fields of investment facilitation policies with timely monitor and review mechanism. Second, SEZs serve as a focal point with better accessibility, transparency, and predictability in investment policies and their implementations. Last, governance mechanism of zones provides enhanced coordination and collaboration within governments and among stakeholders.

First, SEZs can serve as a testing ground for investment facilitation polices. The function of SEZs as policy experimental field have long been acknowledged. China is well known for using SEZs to pilot economic policies, which later have been introduced across the country. In other regions, including South and West Asia, SEZs have been used to test the liberalization of foreign ownership restrictions. Governments can test different policies and new approaches within zones and evaluate policy impacts, institutional setup, and resource allocation to identify priority areas and best practices. With the confined area of SEZs, a timely policy review involving all stakeholders, in particular foreign investors who usually lack channels to participate in host country policy design, is easier to conduct. Improvements thus can be made to ensure that investment facilitation tools and policies are useful, up-to-date, and respond to investors’ needs. With first-hand experiences in zones, government officials will be able to share their expertise in the nationwide implementation with their peers.

Second, SEZs serve as focal points of investment facilitation measures. Investment facilitation measures can be relatively cheap compared to expensive promotion measures, but their implementation is no less difficult as they normally require enhanced coordination among government agencies. Providing clear and up-to-date information on investment regime can be as simple as a click on an upload button, but it can also be mission impossible to some countries, as it requires political willingness to endorse policy transparency, ready IT infrastructure, and human capital. The confined areas of zones make providing such services easier and cheaper, and the promotion measures of zones that are already in place can be converted or added to investment facilitation measures. For example, many governments have marketed their single-window service in SEZs as an investment attraction factor, which is also an important facilitation measure. It is more noticeable within zones when application of investment regulations policy is inconsistent or arbitrary, and suggestions or complaints by investors are much easier to be heard and addressed with zone authorities acting as the lead agency.

Last, governance mechanism of SEZs provides enhanced coordination and collaboration in implementing investment facilitation measures. As complex and different as the institutional setup of SEZs is globally, the broad institutional models of zones are similar among countries with regards to the general structure and the principal actors involved (governments, SEZ authorities, zone developers, operators, and users). Most countries have established an individual SEZ authority with the mandate to initiate and coordinate on investment attraction programs of SEZs. Such authority can coordinate with different agencies within governments and build constructive stakeholder relationships in investment practices. In addition to offering investors seamless access to public services, this designated authority helps to improve the country’s investment environment by communicating with relevant government institutions about recurrent problems faced by investors, which may require changes in investment legislation or procedures in general, the coordinated governance mechanism of SEZs. This coordinated mechanism ensures the equivalent of a whole-of-government approach to investment facilitation. The whole-of-government approach, emphasized by UNCTAD’s Global Action Menu for Investment Facilitation, ensures public services agencies working across portfolio boundaries to achieve a shared goal and an integrated government response to particular issues.Footnote 18

There have already been some efforts to combine investment facilitation together with SEZs. On the one hand, SEZ authorities, zone developers, and IPAs have put more emphasis on providing investment facilitation measures in zones as an attraction for investors. Such measures include simplified investment approval processes and expatriate work permits, removal of requirements for import and export licenses, accelerated customs inspection procedures, and automatic foreign exchange access. Besides such regular investment facilitation measures, targeted investment facilitation measures can also be developed based on the zone context, objectives, and investor profiles. For example, in zones specialized in the IT industry, simplifying the application process of connecting to high-quality digital infrastructure and minimizing the costs thereof can be appealing to potential investors.

On the other hand, national authorities are also trying to help SEZs benefit from their national investment facilitation efforts, with the support from international organizations. International organizations have provided dedicated capacity building and technical assistance programs in promoting investment facilitation, encouraging countries to participate in international dialogues on investment facilitation and help implement investment facilitation measures. For example, UNCTAD has developed three systems, eRegulations, eSimplification, and eRegistration,Footnote 19 under its Business Facilitation Programme, to assist governments in developing countries to document and simplify administrative rules and procedures, which are at the core of investment facilitation. For example, Viet Nam became the first country in Asia to implement eRegulation system in 2015, with a national portal and seven provincial eRegulations platforms dedicated to SEZs. After the implementation of these platforms, the process of registering companies has been significantly reduced, and forms required by different administrations were merged into one. The provincial systems have highlighted information of industrial zones and procedural guidance on operation in industrial zones, tech parks, and outside of zones. For a country with 326 industrial zones,Footnote 20 it is of vital importance for zones to be seen as the first step to win. These investment facilitation tools have played an irreplaceable role for SEZs to attract investment, and the experience learned from these SEZ single windows can be replicated and implemented nationwide as the feasibility of these measures is well proven.

9.6 Looking Ahead: Challenges and Opportunities

The full-scale impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the world economy cannot be underestimated. The disruption it has caused to economic globalization is profound. Global foreign direct investment collapsed in 2020 and there was a very fragile recovery in 2021.Footnote 21 It exacerbates the competitive pressure on SEZs for foreign investment as the pool of global mobile investment has shrank significantly. SEZs in developing countries are expected to be severely hit as a result of their reliance on investment in global value chains (GVCs) intensive and resource-processing industries. SEZs under construction or in planning could be suspended due to lack of funds from governments or shortage of investment. Existing SEZs also face pressure on attracting potential investors. In particular, FDI in manufacturing industries, which accounts for the majority of activities in SEZs in developing countries and is crucial for industrialization of developing countries, is likely to continue its decline. Many specialized SEZs that are developed on vertical specialization and value capture in GVCs will see diminishing returns and increasing divestment, relocations and investment diversion of foreign investors.

However, it does not necessarily lead to a halt in SEZ development. After the global financial crisis in 2008, governments have responded to the increasing competition for FDI with new types of SEZs with sizable financial incentives. SEZs will continue to play an important role in attracting FDI in the post-pandemic world. In addition, the pandemic has demonstrated the importance of a stable and resilient supply chain for global production. The effort of multinational enterprises and other investors to diversify supply bases and build redundancy and resilience will bring opportunities for SEZs. SEZs are ready industrial bases that can be transformed relatively easily to meet the needs of different investors. Zones that have focused on providing raw materials now have the opportunity to move up the value chain by attracting resilience-targeted processing industries. Zones aiming at regional markets and distributed manufacturing are also likely to benefit from more investment as regional market-seeking investment is likely to increase. This will give further impetus to the development of regional zones, cross-border zones, and other forms of international cooperation zones.

At the policy front, however, after the initial emergency investment policymaking that characterized the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2021 has witnessed the investment policymaking in developed and developing countries heading in contrasting directions. Developed countries expanded the protection of strategic companies from foreign takeovers, in a continuation of a trend toward tighter regulation of investment. Conversely, developing countries continued to adopt primarily measures to liberalize, promote or facilitate investment, confirming the important role that FDI plays in their economic recovery strategies. Investment facilitation measures constituted almost 40 percent of all measures more favorable to investment, followed by the opening of new activities to FDI (30 percent) and by new investment incentives (20 percent) in developing countries.Footnote 22 The global experience shows that apart from the short-term and context-specific investment policy responses to crises, some investment policy effects may persist for some time.

As the pandemic has made online service a must instead of an option, it has incentivized governments to accelerate the utilization of online tools and e-platforms. In some countries, online platforms become the only channel to register business, including the business establishments in SEZs. UNCTAD data show that the number of countries with digital information portals increased from 130 to 169 and those with digital single windows from 29 to 75 since 2016.Footnote 23 It significantly improves the accessibility and transparency in investment policies and regulations and procedures, echoing what UNCTAD Global Action Menu for Investment Facilitation calls for.

With the accelerated digitalization process, IPAs have also undergone a transformation to respond to the challenges brought by the pandemic. IPAs worldwide have actively transformed their on-site services to online virtual service, which also benefits investors as it helps save time and costs of investors for making site visits. The marketing activities of IPAs have focused more on reassuring investors of a welcoming investment climate and on specific sectors and investment opportunities emerging from renewed national priorities and a growing demand in sectors such as health, food, and agriculture and tech-related sectors.Footnote 24

Going forward, IPAs need to be involved more in the policymaking process as an important agency for investment facilitation. Traditionally, almost all countries have mandated their IPAs to both promote and facilitate investment, as well as providing aftercare services. In some countries, marketing SEZs rely mostly, if not solely, on IPAs. However, IPAs often find themselves to have relatively weak influence on investment policymaking, and their voice advocating complaints and concerns of investors goes unheard as they are more of the role of policy implementation than policymaking. Their firsthand experience from investor promotion and facilitation make them value assets in investment policy formulation and assessment (e.g., in the design of SEZ programs). Their capacity in providing post-investment or aftercare services also needs to be strengthened. By identifying issues during and after the realization of investment project, IPAs can bring concrete suggestions back to government agencies and promote a continuously open and investment friendly environment. In addition, effective aftercare services could help prevent and/or resolve any potential dispute by identifying issues at an early stage and avoiding further escalation to investor–state dispute settlement procedures.

Another factor that could have far-reaching impact on the development of SEZs and investment facilitation is the new industrial revolution, in particular the adoption of robotics-enabled automation, enhanced supply chain digitalization, and additive manufacturing. New types of SEZs and innovative investment facilitation strategies are inspired and developed by these new technologies. Technology-based SEZs such as high-tech, biotech, and 3D-printing zones have seen fast growth in recent years. Such zones emphasize the need of facilitation services in terms of access to skilled resources, labor training, high level of data connectivity, and digital platform and service providers.

The potential influence of the negotiation under the WTO for an investment facilitation for development agreement cannot be overlooked. On September 25, 2020, participants in the structured discussions on investment facilitation for development at the WTO began formal negotiations. Participating WTO members have mostly discussed the following four topics: improving the transparency and predictability of investment measures; simplifying and speeding up investment-related administrative procedures; strengthening the dialogue between governments and investors; and promoting the uptake by companies of responsible business conduct practices, as well as preventing and fighting corruption and ensuring special and differential treatment, technical assistance, and capacity building for developing and least developed countries.Footnote 25

The measures under discussion have shared features with many existing measures in SEZs, such as establishing online portal to promote accessibility and transparency in investment policies and procedures, single-window or one-stop shop to deliver government services to businesses within SEZs, and shortening application processing time and the use of time-bound approval processes. SEZs can become a tool for relatively fast implementation of investment facilitation commitments in countries where a nation-wide implementation may be difficult due to technical and/or financial reasons. SEZs can also serve as a test field for governments when they decide to unilaterally provide more favorable conditions to foreign investors or investors of a certain sector without violating their international obligations.

It is undeniable that a national investment facilitation program aiming at improving business environment as a whole may erode some of the advantages SEZs currently enjoy. However, SEZs are more than providing a business-friendly environment. Many benefits SEZs can offer the investors, as elaborated in previous sections, are beyond the scope of investment facilitation, for example, better infrastructure, cluster effect, and talent pools. SEZs can be the winning edge of one country’s attraction for foreign investment as an overall welcoming business environment with investment facilitation measure fully implemented serving as the ground.

9.7 Conclusion

SEZs and investment facilitation are key industrial and investment policy tools widely used around the world. They complement each other and can be mutually reinforcing. SEZs have a unique advantage in developing and implementing investment facilitation measures. Meanwhile, investment facilitation can be a key differentiator for SEZs. Some 500 SEZs are in the pipeline for development in the coming years, and countries are making considerable effort in investment facilitation. However, this is taking place in a shrinking pool of efficiency-seeking investment. Competition for global mobile investment will be more intense as incentive-based investment promotion activities are becoming increasingly homogeneous. Countries will rely more on investment facilitation and a friendly and enabling investment environment to win the competition.

The crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the transformation of international production in the next decade have brought new challenges and opportunities to investment policymakers. Confronting the challenges and capturing the opportunities require innovative thinking in SEZ development and investment facilitation. Efforts need to be made to combine SEZs and investment facilitation measures to maximize their contributions to countries’ economic growth. During this process, SEZs have the opportunity to transform to a new-generation SDG model zones with a strategic focus on SDG-oriented investment, the highest level of environmental, social, and governance standards and compliance, and promotion of inclusive growth through linkages and spillovers.Footnote 26 And investment facilitation measures can be more target-driven and benefit from their experimental tests in SEZs. International organizations, such as UNCTAD, outward investment agencies, and IPA association, can play an important role in facilitating this process. If international consensus on investment facilitation is to be reached, technical assistance will be essential in its implementation.