Introduction

There is a substantial variation in national suicide rates, which has been attributed to socio-economic factors (Lorant et al. Reference Lorant, Kunst, Huisman, Costa and Mackenbach2005; Stuckler et al. Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and Mckee2009; Yur'yev et al. Reference Yur'yev, Varnik, Sisask, Leppik, Lumiste and Varnik2013) and genetic predispositions (Marušič & Farmer, Reference Marušič and Farmer2001), as well as to religious or cultural influences that vary between countries (Knox et al. Reference Knox, Conwell and Caine2004). So far, a few studies have investigated the relationship between the population attitude and the suicide rates, examining for example the permissive attitude towards suicide in a country with higher suicide rates (Stack & Kposowa, Reference Stack and Kposowa2008). A recent comparative study of two neighbouring European regions (Flanders and The Netherlands) showed more self-stigma, shame and negative attitude towards help-seeking in Flanders, the region with considerably higher suicide rates (Reynders et al. in press). This finding raises the question whether mental illness stigma could play a role in explaining differences in suicide rates across several countries. Mental illness stigma has been shown to reduce the perceived need for help (Schomerus et al. Reference Schomerus, Auer, Rhode, Luppa, Freyberger and Schmidt2012), impair adherence to treatment (Sirey et al. Reference Sirey, Bruce, Alexopoulos, Perlick, Raue, Friedmann and Meyers2001), decrease self-esteem and hope (Corrigan et al. Reference Corrigan, Rafacz and Rüsch2011) and increase social isolation and withdrawal (Link et al. Reference Link, Struening, Rahav, Phelan and Nuttbrock1997; Angermeyer et al. Reference Angermeyer, Beck, Dietrich and Holzinger2004; Thornicroft et al. Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius and Leese2009; Lasalvia et al. Reference Lasalvia, Zoppei, Van Bortel, Bonetto, Cristofalo, Wahlbeck, Bacle, Van Audenhove, Van Weeghel, Reneses, Germanavicius, Economou, Lanfredi, Ando, Sartorius, Lopez-Ibor and Thornicroft2013) – factors that could contribute to higher suicide rates.

Stigma is a collective phenomenon, mirroring the cultural significance of having mental illness in a society. Recent cross-national studies link variations in population levels of stigma to individual outcomes such as self-stigma, help-seeking preferences or unemployment (Mojtabai, Reference Mojtabai2010; Evans-Lacko et al. Reference Evans-Lacko, Brohan, Mojtabai and Thornicroft2012, Reference Evans-Lacko, Knapp, Mccrone, Thornicroft and Mojtabai2013), demonstrating that the degree of stigma in a country has implications for the way mental illness is experienced in that country.

In this study, we examine the relationship between the desire for social distance from persons with mental illness and the national suicide rates. Specifically, we use the percentage of respondents in a country stating that they are comfortable talking to a person with mental health problems as an indicator of a low desire for social distance, or of social acceptance. We hypothesise that higher levels of social acceptance are associated with lower suicide rates, even after controlling known socio-economic predictors of suicide.

Methods

Eurobarometer survey

We examined the data on the prevalence of stigma in a country from the Eurobarometer survey 2010 (European Union, 2010). Eurobarometer survey data were collected via face-to-face interviews among European Union citizens (n = 26 800 in 2010, approximately 1000 individuals per country per year). Multi-stage random (probability) sampling was used in each country. For our analysis, we included all 25 countries which also had data on suicide rates as compiled by Eurostat (European Commission, 2013): Greece, Cyprus, Italy, Spain, Malta, United Kingdom, Netherlands, Sweden, Bulgaria, Germany, Luxembourg, Romania, Ireland, France, Austria, Portugal, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Finland, Slovakia, Estonia, Poland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania.

As an indicator of public stigma, we used an item on social distance from persons with mental health problems from the Eurobarometer 2010 survey. The item asks individuals: ‘Which of the following two statements best describe how you feel: (1) You would find it difficult talking to someone with a significant mental health problem? or (2) You would have no problem talking to someone with a significant mental health problem?’ Respondents were required to select either statement (1) or (2), a third answer possibility was ‘(3) don't know’. Those who endorsed the second statement were categorised as feeling comfortable talking to someone with a mental health problem, indicating a low desire for social distance. For reasons of simplicity, we use the term ‘social acceptance’ instead of ‘low desire for social distance’. Using population weights for each country, the country level of social acceptance was computed as a weighted average (%).

Socio-economic indicators

Several studies have linked worsening economic conditions such as higher unemployment rates and lower gross domestic product (GDP) to higher suicide rates (Lundin et al. Reference Lundin, Lundberg, Allebeck and Hemmingsson2012; Wahlbeck & McDaid, Reference Wahlbeck and Mcdaid2012; Yur'yev et al. Reference Yur'yev, Varnik, Sisask, Leppik, Lumiste and Varnik2013). Widening economic inequalities may increase exclusion of vulnerable groups and has also been linked to increased suicide rates (Hong et al. Reference Hong, Knapp and Mcguire2011). As potential country-level socio-economic determinants of suicide rates, we thus investigated three socio-economic indicators in 2010: national unemployment rate (in % of the labour force), the Gini-index as an indicator of inequality (range, 0–1, higher values indicate greater inequality) and decline of the GDP per capita since 2008 (in %, reflecting the economic consequences of the economic crisis) (European Commission, 2013).

Suicide rates

National suicide rates for 2010 were taken from the Eurostat database (European Commission, 2013). The figures represent the age standardised death rate per 100 000 people from suicide and intentional self-harm (ICD-10 codes X60-X84, Y87.0). Although the reporting of deaths by suicide follows different procedures in each country, it is generally agreed that these differences do not introduce a systematic bias (Stuckler et al. Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and Mckee2009). To account for potential differences in under-reporting suicides in a country, however, we repeated our analyses including deaths due to ‘events of undetermined intent’, which is commonly assumed to contain a certain proportion of undetected suicides (Värnik et al. Reference Värnik, Sisask, Värnik, Arensman, Van Audenhove, Van Der Feltz-Cornelis and Hegerl2012). We thus generated a new variable with a combined rate of suicides and undetermined deaths for each country. Suicide rates and combined death rates did correlate highly (r = 0.93, p < 0.001).

Statistical analysis

We used a stepwise approach to determine the relationship between country-level stigma and suicide rates. First, we examined pairwise correlations between all variables. Second, we performed a series of linear regression analyses with suicide rates as the dependent variable, entering country-level stigma first and then adding the economic indicators. Examination of a scatter-plot relating suicide rates to stigma prevalence showed particularly high suicide rates and stigma for Lithuania. To reduce the impact of this outlier, we excluded Lithuania from our final model. All analyses were conducted with STATA, version 12.1 (StataCorp, 2011).

Results

Table 1 shows pairwise correlations between suicide rates, stigma and economic indicators. Higher suicide rates significantly correlated with lower social acceptance of persons with mental illness and with GDP decline between 2008 and 2010. Economic indicators showed the expected inter-correlations: greater decline in GDP was correlated with higher inequality and higher unemployment rates, and greater levels of inequality were correlated with higher unemployment rates.

Table 1. Pairwise correlation of country-level suicide rate, stigma, economic indicators and country-level psychological distress in 25 European countries in 2010

Note: MHP, mental health problems; GDP, gross domestic product.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

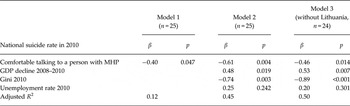

Table 2 shows the results of our regression analyses. The negative relationship between national suicide rates and country-level social acceptance of persons with MHP persisted when economic indicators were entered into the equation, resulting in a standardised coefficient of −0.46 (p = 0.014) in the final model (excluding Lithuania). This model explained 50% of the variance of national suicide rates (Table 2). Repeating these analyses with combined rates of suicide and undetermined death as the dependent variable yielded similar results: comfortably talking to persons with MHP was negatively related to the combined death rate (all 25 countries: β = −0.62, p = 0.004; excluding Lithuania: β = −0.51, p = 0.011, adjusted R2: 44 and 42%, respectively).

Table 2. Aggregate predictors of national suicide rates in 2010. Linear regression analysis; standardised coefficients (β)

Note: MHP, mental health problems; GDP, gross domestic product per capita.

Discussion

We found a significant inverse relationship between national suicide rates and social acceptance of persons with mental health problems in a cross-sectional analysis using country-level data from 25 European countries. This relationship also held true when including rates of undetermined deaths per country. This is the first study linking national levels of stigma towards persons with mental illness to national suicide rates, lending support to the hypothesis that stigma is associated with higher prevalence of suicide. Before discussing hypotheses on potential mechanisms behind this link, however, it is important to consider the limitations of this study.

Limitations

Looking at stigma and suicide rates as collective phenomena, we used cross-sectional, aggregate-level data as both dependent and independent variables. Our results thus cannot prove that there is a relationship between country-level stigma and individual suicidal behaviour (‘ecological fallacy’), but rather encourage further research following this hypothesis. We did not examine the role of individual risk factors for suicidal behaviour nor individual reactions to stigma. Previous studies combining individual-level data on stigma experience and country levels of stigma have, however, shown that aggregate stigma levels have a negative impact on individual experiences of mental illness (Mojtabai, Reference Mojtabai2010; Evans-Lacko et al. Reference Evans-Lacko, Brohan, Mojtabai and Thornicroft2012, 2013). The role of stigma in individual suicidal behaviour has only just started to be examined, and, for pragmatic reasons, has been restricted to retrospective analyses of attempted suicides (Bruffaerts et al. Reference Bruffaerts, Demyttenaere, Hwang, Chiu, Sampson, Kessler, Alonso, Borges, De Girolamo, De Graaf, Florescu, Gureje, Hu, Karam, Kawakami, Kostyuchenko, Kovess-Masfety, Lee, Levinson, Matschinger, Posada-Villa, Sagar, Scott, Stein, Tomov, Viana and Nock2011). Although suicide rates across Europe have been regarded as a relatively unbiased outcome measure (Stuckler et al. Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and Mckee2009), we accounted for potential differences in suicide recording in a country by repeating our analyses including deaths of undetermined intent. Nevertheless, the validity of our single-item stigma indicator could be questioned. Its relation to individual stigma experience in multilevel analysis (Evans-Lacko et al. Reference Evans-Lacko, Brohan, Mojtabai and Thornicroft2012) however indicates that it is indeed reflective of the degree of openness towards persons with mental illness in a country. It is a particular strength of this study that prevalence of stigma within countries was elicited using large nationally representative samples of approximately 1000 respondents per country.

As in all cross-sectional studies, we cannot exclude the possibility that ‘reverse causality’ contributed at least in part to the observed relationships. Theoretically, high-suicide rates could frame negative public attitudes towards mental health problems, because more persons have negative, suicide-related experiences with mental illness. In contrast to this assumption, however, a recent study in Australia found that exposure to suicide was associated with better suicide literacy, and was unrelated to stigmatising attitudes (Batterham et al. Reference Batterham, Calear and Christensen2013). In their study, Batterham and co-workers investigated the stigma of suicide rather than the stigma of mental illness, and future research is warranted to explore potential differences between these two types of stigma and their influence on suicide rates. Finally, our study included European countries only. Investigation of a possible relationship between stigma and suicide in more diverse geographical regions and using different study designs is warranted.

Potential mechanisms linking stigma to suicide rates

Being aware that this ecological study does not permit conclusions about the relationship between the experience of stigma and suicide on an individual level, we hypothesise three mechanisms of how stigma could potentially increase the suicide rates. First, according to the stress–diathesis model of suicidal behaviour, psychosocial stressors can increase the suicidality (Van Heeringen, Reference Van Heeringen and Dwivedi2012). Stress-coping models of stigma frame stigma as a social stressor that in turn can lead to negative emotional reactions, social withdrawal and hopelessness among people with mental illness, especially if the perceived threat of stigma and social rejection exceeds the coping resources of the individual (Rüsch et al. Reference Rüsch, Corrigan, Powell, Rajah, Olschewski, Wilkniss and Batia2009).

Second, stigma contributes to the social isolation of a person experiencing a severe mental health problem (Link et al. Reference Link, Cullen, Struening, Shrout and Dohrenwend1989). Social isolation has long been recognised as a risk factor for suicide (Trout, Reference Trout1980). The item on comfort/reluctance in talking to a person with a mental health problem used in this study directly addresses social isolation of affected persons. Barriers to discussing one's mental health status can have particularly serious consequences in a person considering suicide. A more open cultural climate regarding psychological and emotional health problems likely facilitates self-disclosure and help-seeking and could thus prevent suicides, which is in line with the recent findings comparing attitudes towards help-seeking and stigma in a low- and a high-suicide region in Europe (Reynders et al. in press).

Third, collective levels of stigma are predictive of individual stigmatising attitudes in a population (Mojtabai, Reference Mojtabai2010) and of individual self-stigma (Evans-Lacko et al. Reference Evans-Lacko, Brohan, Mojtabai and Thornicroft2012). Studies on predictors of help-seeking have shown that both individual stigmatizsing attitudes and self-stigma are associated with lower willingness to seek help for mental health problems (Vogel et al. Reference Vogel, Wade and Haake2006; Schomerus et al. Reference Schomerus, Matschinger and Angermeyer2009), which could, in turn, increase the individual risk for suicide. Studies combining data on collective levels of stigma and individual level attitudes, help-seeking and suicidal behaviour are needed to establish this hypothetical link.

Of note, we observed significant correlations between social acceptance of persons with mental illness and population level economic distress as measured by GDP decline and a high Gini-index. Higher levels of stigma thus seem to be partly reflective of the level of economic stress in a country (Angermeyer et al. Reference Angermeyer, Matschinger and Schomerus2013).

In conclusion, this study found that country-level stigma surrounding mental illness is related to national suicide rates. More research is needed to establish a link between stigma and suicidal risk at the individual level and to investigate and test potential causal mechanisms. Suicide prevention initiatives should address population-level attitudes and reactions to people with mental illness.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

SEL and RM report personal fees from Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.