Introduction

In August 1941 an engineering worker at Fiat’s at Lingotto was denounced to the police headquarters by means of a signed letter as a ‘vile slanderer and propagator of false and tendentious stories against the PNF and especially against Benito Mussolini, whom he publicly accuses of high treason and responsibility, together with Rodolfo [sic] Hitler, for the current war’….the denunciation was resolved with a simple warning, because it became clear that it was dictated by ‘rancour and mean-minded vindictiveness’ … the plaintiff intended to drive away the engineering worker from his ex-lover … who had taken up with his rival.

This tale of sex, ideology, and the boundary between the two, appears in Luisa Passerini’s 1984 Fascism in Popular Memory (Reference Passerini1987: 147), alongside others of a similar ilk. Passerini’s book is a rare instance of an “everyday” history of Italian Fascism and is one of the only texts cited approvingly by R.J.B. Bosworth in a polemical 2005 essay entitled “Everyday Mussolinism” (Reference Bosworth2005; see also Arthurs, Ebner, and Ferris Reference Arthurs, Ebner and Ferris2017). The target of Bosworth’s polemic in that piece (as elsewhere Reference Bosworth1998; Reference Bosworth2002) is a form of cultural history in which totalitarian fascist ideology is thought to dominate or monopolize all forms of life. He calls instead for an Italianist version of Sheila Fitzpatrick’s “everyday Stalinism” (Reference Bosworth2005: 25), in which fascist ideology is revealed as fragile and relatively easily evaded, especially in the domain of what is called ordinary or everyday life. Though Bosworth notes that Passerini’s book makes little in the way of a conclusive argument, it is in this respect that he cites her as an exemplar of writing on “ordinary life” under Fascism.

Bosworth and Fitzpatrick’s claims about the everyday or the ordinary are part of a much broader family of historical writing that includes the Annales school in France (e.g., Braudel Reference Braudel1981), Alltagsgeschichte in Germany (e.g., Lüdtke Reference Lüdtke, Samuel and Stedman-Jones1982), and the microstoria of Italian scholars such as Carlo Ginzburg (Reference Ginzburg1980). None of these various movements are identical with one another, but they all share a concern with scaling down historical narratives away from “macrostructures” or “Events” and toward Braudel’s “realm of routine” and “ordinary experience.”

The links and crossovers between these various historical approaches and social and cultural anthropology are well known (e.g., Abélès Reference Abélès and Revel1996; Medick Reference Medick and Lüdtke1995; Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal and Revel1996). “The imponderabilia of actual life,” as Malinowski put it (Reference Malinowski1922: 17), have in some sense always been the basic bread and butter of anthropology given its ethnographic methodology and historical preference for “small-scale” societies. As Morgan Clarke has recently pointed out, “Sociocultural anthropology, with its characteristic emphasis on participant observation and hence lived practice, could be seen as having the complex skein of ‘everyday life’ as its normal subject matter” (Reference Clarke2016: 798).

Beyond this broad and longstanding disciplinary preference, a number of recent publications within the field of the anthropology of ethics have claimed “the ordinary” to be the proper domain of ethical life (e.g., Lambek Reference Lambek2010; Das Reference Das2007), and it is to the notion of “ordinary ethics” which Clarke is referring when he argues that in the sense anthropology has always been concerned with ordinariness: “ordinary ethics” surely amounts to “anthropology as usual” (Reference Clarke2016: 799). As an approach in anthropology, “ordinary ethics” also conjures up certain visions of scale: in opposition to the thought that ethics must reside in “transcendent powers of reason” or treat ‘big’ [sic] issues from abortion and doctor-assisted suicide to violent protest” (Sidnell, Meudec, and Lambek Reference Sidnell, Meudec and Lambek2019: 303–4), authors such as Michael Lambek and Veena Das argue that ethics inheres in everyday action and interaction, and that a “descent into the ordinary” (Das Reference Das and Fassin2012: 134) allows for a view of ethics as inherent to and immanent in “the everyday.”

Ordinary ethics is now a significant trend within the broader framework of the anthropology of ethics and morality and has generated a range of critical responses (e.g., Clarke Reference Clarke2014; Laidlaw and Mair Reference Laidlaw and Mair2019; Lempert Reference Lempert2013; Robbins Reference Robbins2016; Zigon Reference Zigon2014). Some of these critical responses argue persuasively for the importance of the transcendent as a location for ethical value (e.g., Robbins Reference Robbins2016); others seek to trouble this very distinction between “the ordinary” and the transcendent (e.g., Clarke Reference Clarke2014; Laidlaw and Mair Reference Laidlaw and Mair2019). As Clarke puts it, the risk of a normative focus on one subject matter to the exclusion of the rest is that “we will just end up arguing about what does and does not count, and for no good reason. We could perhaps more profitably be thinking about how such distinctions are constituted in differing ways in different contexts” (Reference Clarke2016: 798; see also Fadil and Fernando Reference Fadil and Fernando2015).

In this paper I share this interest in examining how “the everyday” and “the ordinary” are distinguished from other domains of life. More specifically, I describe a case in which “the ordinary” is an ethical achievement, rather than a state of affairs.

I do not mean this so much in Stanley Cavell’s sense of “achievement,” as when he describes Romanticism as the discovery of the exceptional nature of the “everyday” (Reference Cavell1979: 463). Rather, I mean it in the more straightforward sense in which Harvey Sacks famously described the work of “doing being ordinary” (Reference Sacks, Atkinson and Heritage1985). As Sacks puts it, “whatever you may think about what it is to be an ordinary person in the world, an initial shift is not think of ‘an ordinary person’ as some person, but as somebody having as one’s job, as one’s constant preoccupation, doing ‘being ordinary.’ It is not that someone is ordinary; it is perhaps that that is what one’s business is, and it takes work, as any other business does” (ibid.: 414). Similarly, I mean “work” in the manner in which other literature in the anthropology of ethics has pointed to the ways values and virtues require cultivation and ethical labour (e.g., Laidlaw Reference Laidlaw2002; Reference Laidlaw2014). In other words, where that literature on ethical reflection and cultivation has often been treated as in opposition to or incompatible with notions of “ordinary ethics,” here I discuss a case in which it is precisely a sense of ordinariness that people strive to cultivate in a more or less reflective fashion.

One of the ways in which anthropologists have described ethical labor performed in other contexts is in relation to moral exemplars (e.g., Humphrey Reference Humphrey and Howell1997; Robbins Reference Robbins, Laidlaw, Bodenhorn and Holbraad2018). Perhaps unsurprisingly, literature on “ordinary ethics” has not been put into sustained dialogue with that on moral exemplarity. Surely if exemplars are anything, they are far from ordinary. They are military or political leaders like Genghis Khan, or Melanesian big men; or like Hitler, Mussolini, Mosley, or Franco, as testified to by the personality cults that sprang up around them.

In her landmark essay on the subject, Caroline Humphrey argues that ethics and morality in Mongolia inhere primarily in the relationship between persons and exemplars and precedents, rather than in rules or customs (Reference Humphrey and Howell1997: 25). Part of her point in making this argument is that Mongolian exemplar-focused morality is immensely variable and changeable: moral subjects may have several different exemplars whom they follow, who may or may not be consistent, and who may be drawn upon for different purposes (ibid.: 39).

To return to Passerini’s vignette and the topic of ordinariness, just as Humphrey’s interlocutors can draw on the example of Genghis Khan in resolving marital problems as well as martial ones (Reference Humphrey and Howell1997: 25), Passerini’s lack of conclusiveness renders her the sort of exemplary historian from whom many different lessons can be learnt. Bosworth’s interest in everyday life as a domain separate and apart from the sphere of ideology and politics is one. She writes of “the original independence of everyday cultural forms” (Reference Passerini1987: 65), and other similar remarks scattered throughout her book suggest a special, ontologically distinct status for everdayness of the sort of which Bosworth approves.

But contrastingly, she also often describes the “shifting boundaries” between ordinary life and politics, as wonderfully encapsulated in the epigraph above. The most striking aspect of the story is that it involves neither the “colonization” of the domain of everyday life by politics, nor the preservation of that domain as a sphere of “resistance” to Fascism (as in Scott Reference Scott1985): instead, the boundary between the two itself is instantiated and policed by the historical actors themselves. The denouncer tries unsuccessfully to politicize his squabble with a love rival, and in response the police declare him “mean-minded” and “vindictive,” pushing his romantic problems back into the sphere of “ordinary life” and out of their political jurisdiction. In other words, neither ideology/politics nor everyday life is “original,” “independent,” or “totalizing” here: rather, it is, as Clarke suggests in the quotation above, precisely the boundary between the two which is at issue for the participants, as they construct both as distinct from one another.

The point the story makes is that “no situation, site, practice, or individual is ‘ordinary’ in itself” (Neveu Reference Neveu2015: 148). Moreover, I would argue, it takes active work—such as the boundary work in Passerini’s story—to produce a sense of ordinariness that can be opposed to other domains. This chimes with a broader point made in recent anthropological work on scale (Lempert Reference Lempert2012; Summerson Carr and Lempert Reference Summerson Carr and Lempert2016), namely that “scale-making” is a practice our interlocutors engage in all the time. The implication (drawn out critically with particular reference to “ordinary ethics” in Lempert Reference Lempert2013) is that we cannot rely on the givenness of the “small-scale,” the “micro,” or an ordinary into which we “descend,” any more than we can on the large scale and the macro. “Interaction” itself is a scale that requires work to construct (ibid.). As a scaling device, “the ordinary” may be as much a product of work by historical and cultural actors as is “the political,” as in Passerini’s story above (and see also Candea Reference Candea2010). One form such work may take, I will suggest here, is instantiating “ordinariness” in specific figures and individuals—think of “Joe the Plumber” (cf. Lempert and Silverstein Reference Lempert and Silverstein2012: 37), or the “uomo qualunque” movement—just as are other values in other sorts of exemplars (Robbins Reference Robbins, Laidlaw, Bodenhorn and Holbraad2018; and see Lempert Reference Lempert2013 for a comparable argument for ritualization as an instrument in constructing “the everyday”).

Indeed, one could also read the everyday men and women described in Bosworth’s article as performing precisely this scale-making work of exemplifying “the ordinary” in his analysis. As historians who have worried about the “representativity” of “everyday life history” have pointed out, the selection of particular cases of ordinary people about whom to write raises the issue of what such ordinary people are intended to be exemplary of, if anything. As Paul de Man has put it specifically with reference to examples: “Can any example ever truly fit a general proposition? Is not its particularity, to which it owes the illusion of its intelligibility, necessarily a betrayal of the general truth it is supposed to support and convey?” (de Man Reference de Man1984, quoted in Højer and Bandak Reference Højer and Bandak2015). In Bosworth’s case, in a sort of reverse version of the Italiani brava gente narrative one often hears in relation to Italian Fascism (in which Italians are too fundamentally good-natured to have ever been properly Fascist), he takes a number of instances of corruption and nepotism to represent or exemplify a sort of characteristic Italian graspingness that prevented them from ever fully succumbing to party ideology. But why should we be any more persuaded by these instances that this mean-mindedness is ordinary in Italy than we are persuaded that good-naturedness is ordinary there?

One of the instances of exemplary ordinariness I will treat in this paper is Mussolini himself, who looks far from ordinary in many ways, resembling more the sort of Genghis Khan-style great leader. Indeed, given the comprehensiveness of work on personality cults surrounding Mussolini (The Cult of the Duce project on Mussolini, for instance; see Gundle, Duggan, and Pieri Reference Gundle, Duggan and Pieri2013), it is not my intention here to add to its coverage of the general character of Mussolini as exemplar, though the exact relationship between “cult figure” and exemplar is no doubt worth exploring further. Instead, I want to focus more narrowly on one aspect of his and others’ exemplarity: that of imputed ordinariness.

For though it might seem axiomatic that exemplars be extraordinary or unusual in some way or another, my aim in this paper is to draw attention to those who are thought to exemplify the quality of ordinariness, whose very everydayness is itself taken to be exemplary.

My aim in drawing attention to such figures is to make both an empirical argument about the uses of ordinariness in one historical and ethnographic context, and a conceptual one about the analytical usage of ordinariness.

My empirical argument focuses on Predappio, the town in which Mussolini was born, which he reconstructed as a monument to his own biography, and which has played host to his remains since 1957. Both ordinariness and exemplarity have played a crucial role in Predappio’s recent history and current existence. As I will describe below, under Fascism Predappio was a vital part of the regime’s myth-making apparatus. It was held up as an exemplar in two key senses: firstly, its reconstruction and transformation from a hamlet of a few hundred people into a bustling small town of ten thousand, a gem of Fascist architecture and urban engineering, the first of the Fascist “New Towns,” made it worthy of exhibition as one of the marvels of Fascist modernism, alongside other new towns like those of the Pontine Marshes, and EUR in Rome. Secondly, however, this whole project of reconstruction was premised on the fact that this was the ordinary village in which the great Duce was born, and this ordinariness was crucial to the reconstruction itself. The myth-making focused on Predappio thus had two dimensions: It was intended to be seen as extraordinary, a modern Fascist cathedral in a desert of small medieval villages (Serenelli Reference Serenelli, Gundle, Duggan and Pieri2013: 99), but the regime’s determination to immortalize Mussolini’s poor peasant upbringing meant that it also had to be seen as fundamentally ordinary, an Italian town like any other, with which the tourists who came to see it could identify. Under Fascism, in other words, Predappio was exemplary of something very special (Fascist modernism) emerging from something very typical (an average peasant life in the Romagna).

I compare this historical instance of an “ordinary exemplar” with an ethnographic case. This component of my argument focuses on contemporary Predappio, in which I have been carrying out fieldwork since 2016. The town remains notorious for its association with Fascism and the presence of Mussolini’s remains still draws thousands of tourists every year, many of whom have far-right political sympathies (Heywood Reference Heywood2019; see also Gretel Cammelli Reference Gretel Cammelli2015; Holmes Reference Holmes2000; Reference Holmes2016). What has fallen away from Predappio’s exemplarity today as far as outsiders are concerned is the dimension of ordinariness. Without the regime’s insistence on Mussolini exemplifying the typical early life of any poor Italian peasant, what remains is Predappio’s spectacularly singular urban fabric and its status as a symbol of deeply felt political and ideological contestations over the afterlife of Fascism in Italy. To most people in Italy, in other words, Predappio is now anything but ordinary in any sense whatsoever. Yet, as I describe, “the ordinary” is exactly what its inhabitants reach for in contesting such readings of their home. Ordinariness is what they valorize and work toward, in contrast to their extraordinary status in the wider popular imaginary. I focus on one historical figure—Giuseppe Ferlini, the town’s first postwar Mayor—whom Predappiesi invoke regularly and often as an exemplar, in contrast with the man whom everyone else associates with their home, namely Mussolini. As with invocations of Mussolini in Predappio under the regime, Ferlini is valorized by contemporary Predappiesi for his ordinariness. Yet, unlike Mussolini’s ordinariness under Fascism, Ferlini’s ordinariness is not opposed to the extraordinariness of some other social class (the liberal bourgeoisie, for instance) or to his own later greatness. Instead, it is opposed to the extraordinary and highly politicized status of Mussolini himself as Predappio’s most famous son. In other words, Predappiesi valorize Ferlini’s ordinariness because it allows them to contest understandings of their home that make it emblematic of Italy’s Fascist past and the ongoing political tensions over this past.

In making this comparative argument, my intention is also to make a broader conceptual claim about the category of ordinariness. Again, I think it a mistake to treat “the ordinary” or “the everyday” as if they were purely substantive categories comprised of phenomena such as eating, sleeping, or having marital disputes. Instead, I argue, actors (and analysts) work to construct the meaning of ordinariness, and while in doing so they will often tie it to distinct substantive phenomena, they will also do so relationally and in opposition to other phenomena. I will describe this process at work in the case of Predappio, but I think it also occurs in our own scholarly usage of the terms. Hence a paradox: the concepts of “the ordinary” and “the everyday” are amongst the most portable in our analytical vocabulary: witness “everyday Stalinism” = “everyday Mussolinism” as a specific example. We regularly invoke them as categorical forms: so, in addition to the rather specific examples of “everyday Stalinism” and “everyday Mussolinism,” and the much more general “everyday life” or “ordinary life” (e.g., Schielke Reference Schielke2009) or the “ordinary ethics” we have met (Das Reference Das2007; Lambek Reference Lambek2010), we also have “everyday” resistance (e.g., Scott Reference Scott1985) “everyday” utopias (Cooper Reference Cooper2014); “everyday” religion (e.g., Ammerman Reference Ammerman2007); “everyday” politics (e.g., Boyte Reference Boyte2004); “everyday” shame (Probyn Reference Probyn2004); and “everyday” violence (e.g., Bourgois Reference Bourgois1998), to give just a few examples. Yet in subsuming such phenomena within the form of “the everyday,” our laudable intention is precisely to point to the ways in which such phenomena are actually lived, in all of their messy, contingent, complex, and distinct reality, to bring them “down” into the granularity of life, and away from the realms of formal, general categories. The paradox resides in the fact that “the everyday” and “the ordinary” are themselves formal, general categories. Perversely, then, “everyday life” is supposed to point to the most fine-grained particulars of existence (and of course the content of our actual descriptions does exactly this, when at their best); yet by describing such particulars with those simple two words, we imply it is always and everywhere the same “everyday life.”

I will aim to capture this ambiguity with the idea of the “ordinary exemplar.” I will describe two different versions of ordinary exemplarity at work: in one version, as in the case of Mussolini, apparently “typical,” “normal,” or “representative” traits can be deployed by populist movements in the production of exemplary figures (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017: 78). It was not that Mussolini acted as an exemplar of ordinariness as a virtue in itself, but that his ordinariness formed the backdrop to his exemplary traits (strength of will, masculinity, vision, etc.) that made him a cult figure, and thus made that exemplarity all the more striking. The temporality of this “ordinary exemplar” is from an imputed past ordinariness to an extraordinary present.

The other version is found in Ferlini, who is exemplary precisely because he is ordinary, because in contemporary Predappio ordinariness is itself extraordinary. The temporality in this case is reversed, and a present extraordinary status is contrasted with an aspiration for an ordinary future. Here the backdrop is Predappio’s extraordinary status as an emblem of Italy’s contested Fascist past, and so it is ordinariness itself that comes to seem exemplary. In this way, Ferlini functions for Predappiesi similarly to the “ordinary exemplars” of our historical and anthropological accounts, such as Bosworth’s: he concretizes the abstract value of ordinariness itself, in contrast to some other, perhaps putatively “more” abstract category, such as politics, ideology, or transcendence. Just as accounts such as Bosworth’s challenge what they allege to be a “typical” emphasis on the extraordinary power of, say, fascist ideology—“much of the rest of the recent historiography of the Fascist years” (Reference Bosworth2005: 26)—by means of exemplars of ordinary life, so Predappiesi contest the imbrication of their home in grand historical narratives of Fascism and anti-Fascism by means of their own “ordinary exemplar.”

New Predappio and Mussolini, “the man like you”

As in other totalitarian regimes, the Fascist party laid a great deal of emphasis on the exemplary qualities of its leader. Christopher Duggan, in a volume devoted to the “cult of the duce” (Reference Duggan, Gundle, Duggan and Pieri2013), noted that the notion of Mussolini as l’uomo della providenza (“the man of providence”) had been around since the birth of the Fascist movement in 1919. But it was in 1925, after the crisis brought on by the assassination of socialist parliamentarian Giacomo Matteotti, that its development began in earnest. Several failed attempts on Mussolini’s life led to his being compared to Christ in parliament, to Church bells ringing across Italy, and to the Pope reportedly suggesting he was being protected by God (ibid.: 37). Though this was pragmatically convenient at the time for a regime suffering from a lack of ideological coherence and buffeted by the Matteotti scandal, later essays in the same volume attest to the persistence of the cult of personality both throughout the ventennio and into the postwar period. That attempts were made to transform Mussolini into the ultimate moral exemplar for Fascism is very clear, in other words. Moreover, my specific ethnographic focus, the small town of Predappio, in Emilia-Romagna, had a special place in Mussolini’s personality cult from its very outset in 1925, and it retains that place today.

Predappio has existed, in some form or another, since Roman antiquity, and its name is alleged to derive from the original Latin title given to the hill fort at the foot of the Apennines: Praesidium Domini Appi. Until its transformation into Predappio Nuova (New Predappio) in the 1920s, Dovia, or Dvi, as it was known in dialect, was a tiny hamlet located about 3 kilometers down the hill from the original Predappio (now Predappio Alta), named for the two roads (due vie: Dovia) that it straddled, one to Predappio Alta and one over the Apennines, towards Tuscany and Florence. In 1894 there were 503 inhabitants in Predappio Alta, and 186 in Dovia (Proli Reference Proli2013: 61).

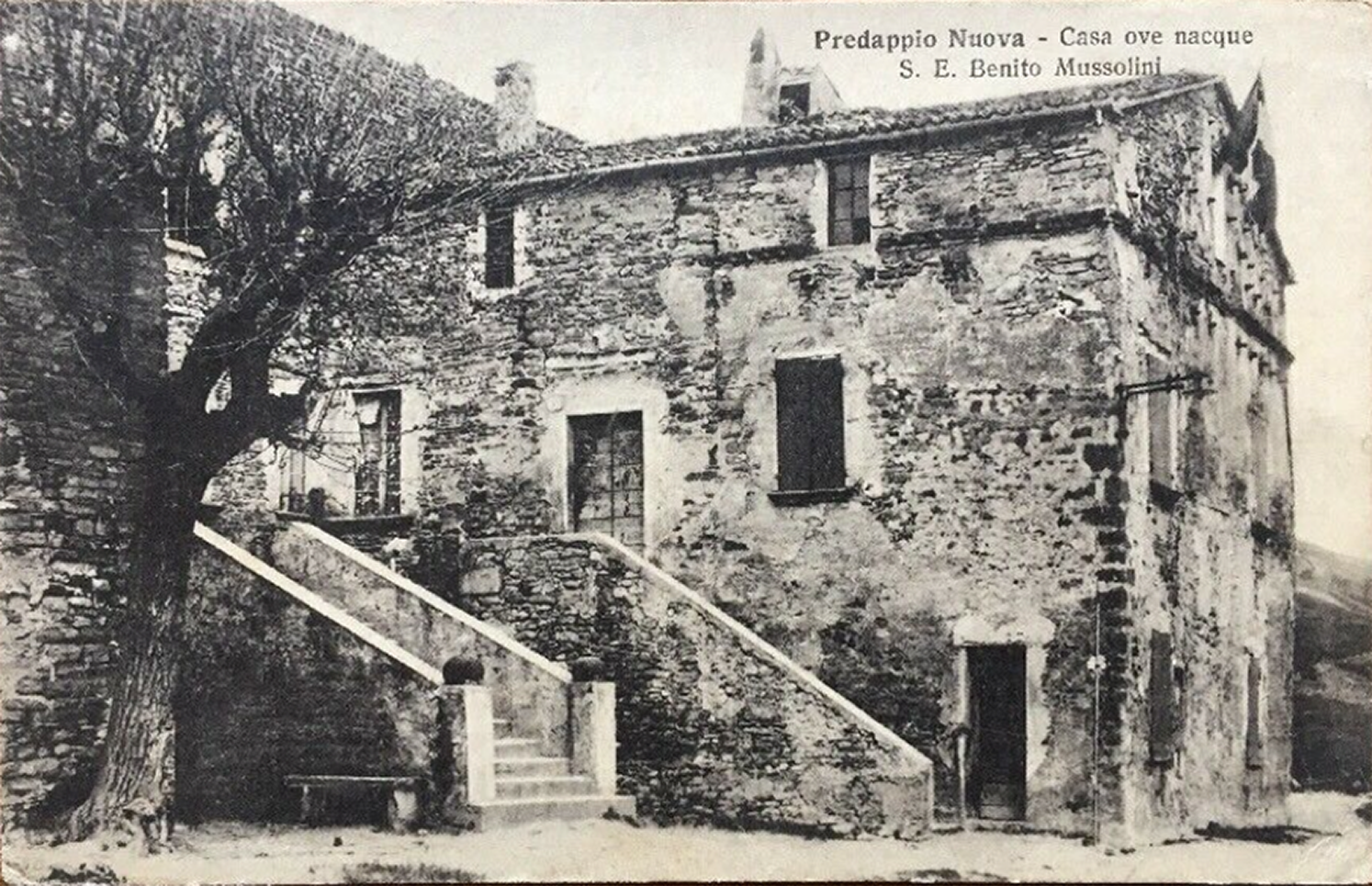

Mussolini was born in Dovia in 1883, and almost immediately after he took power in 1922, he began the process of transforming it into a major site of myth-making around his personality. He paid his first ceremonial visit there as head of government on 15 April 1923, accompanied by a selection of national dignitaries. For the occasion, the town’s main street was renamed in his honor (a name it would retain until the end of the war) and the house in which he was born was gifted to him, decorated with garlands and flags. Local and national newspapers celebrated the visit with extensive coverage and commemorative postcards were printed (see image 1). Within months reconstruction work had begun, and over the course of the next fifteen or so years Dovia was transformed from a hamlet of a few hundred people into an entirely new town of over ten thousand: New Predappio. Predappio as it exists today owes that existence to Mussolini, and to the accident of his birth there.

Image 1. Commemorative postcard depicting the birth house of Mussolini.

Source: Saffi Library, Piancastelli Collection.

Predappio’s reconstruction included a new municipal headquarters for the comune (in the schoolhouse in which Mussolini’s mother used to teach—see image 2); an impressively-sized church in the main square; a hospital; a carabinieri barracks; a post office; a primary and secondary school; the local headquarters of the Fascist youth movement and of its official trade union; a cinema; an airplane factory and flight-testing facility; extensive accommodation for associated workers; and a flagship party headquarters for the Italian Fascist Party, also designed to host visiting dignitaries (see Gatta Reference Gatta2018). The reconstruction process was attended by much pomp and circumstance throughout, usually focused, unsurprisingly, on Mussolini himself. In 1925, Fascist Party national secretary Roberto Farinacci and Quadrumvir Italo Balbo attended the laying of the foundation stone of a church named in honor of Mussolini’s mother in the town (an occasion filmed for propaganda purposes—see Proli Reference Proli2020), declaring its inauguration an occasion for a “renewed oath”: “Duce, we are always at your command, in both spirit and body” (Duggan Reference Duggan, Gundle, Duggan and Pieri2013: 35). The centerpiece of this visit was the inauguration of a commemorative plaque at the house Mussolini was born in, declaring him a great statesman and savior of the nation.

Image 2. Commemorative postcard depicting the newly built town hall in Predappio.

Source: Saffi Library, Piancastelli Collection.

The new town was constructed around two main squares, both of which were dominated by Mussolini’s heritage: the first framed the house in which he was born, and the second the former schoolhouse in which his mother taught, which became the town hall, in front of which a garden was laid out that included enormous fasces made of topiary. The local cemetery was also reconstructed around the tomb in which the bodies of his parents were placed (his father had died apart from his mother and had been buried in the nearby town of Forli, until his exhumation and transfer to Predappio).

As Sofia Serenelli has described, as early as 1919 Predappio had been a place of pilgrimage for Fascists (see also Proli Reference Proli2020; Baioni Reference Baioni and Isnenghi1996), but from around 1926 such pilgrimages took on a national character, regulated and organized by the state, and with a certain fixed form (Serenelli Reference Serenelli, Gundle, Duggan and Pieri2013: 94). Postcards depicting Predappio during and after the reconstruction process were mass produced and sold throughout Italy (see image 2; and D’Emilio and Gatta Reference D’Emilio and Gatta2017). A propaganda office was opened in the new and monumental party headquarters building in the town, tasked with organizing local tours and publishing guidebooks and photo albums (Proli Reference Proli2020). From the outset, then, Predappio was at the heart of the project of making Mussolini into a myth.

For all these reasons, Mussolini himself does not fit the picture of an “ordinary exemplar” very well, but my point is not that it was ordinariness, above any other characteristics, that made him a cult figure and exemplar to many Italians. Rather, as Simona Storchi points out in her analysis of one of the first biographies of Mussolini, written by his then-lover Margherita Sarfatti, his humble roots were an important part of the myth surrounding him (Reference Storchi, Gundle, Duggan and Pieri2013: 52). This was especially true when it came to Predappio.

Predappio was built around Mussolini’s own biography, then, as a sort of giant, open-air museum to his early life (and to the prowess of Fascist urban engineering). Given that this early life was spent as the son of the local blacksmith and schoolteacher in comparative poverty, it was ripe for exploitation in the service of constructing Mussolini, “the man like you, with your qualities and faults, with all that goes to make up the essential elements of that special human nature that is the nature of Italians” (Sarfatti, quoted in Storchi Reference Storchi, Gundle, Duggan and Pieri2013: 52). As Serenelli observes, some of the first items of propaganda based on Predappio were postcards depicting Mussolini visiting “the ‘humble’ grave of his mother, and surrounded by his ‘own people’ in front of the house in which he was born” (Reference Serenelli, Gundle, Duggan and Pieri2013: 95). In Farinacci’s speech at the inauguration of New Predappio, quoted earlier, he stressed “the social rank of Fascism … which is proletarian, and, above, all rural” (ibid.: 97). In 1935, Mussolini personally unveiled a plaque at the house in which his father Alessandro was born which claimed the site would explain “what is meant by austerity of life” (ibid.: 102). This was a comparatively rare instance of attention paid to Alessandro, however, since his life as a local socialist politician made him a less-than-straightforward figure for the regime to draw upon. Mussolini’s mother, though, an ordinary schoolteacher with no such political complications, was the focus of much attention, and she had a church and a nursery school named after her in Predappio.

Mussolini’s birth house is an interesting instance of the emphasis on his humble roots. It sits directly above the second of Predappio’s two large squares and is the central vista of an elaborate ceremonial arch. It was isolated from surrounding houses by the construction of a tree-lined avenue around it and was originally reachable from the square by walking through the arch and a gate decorated with the Fascist emblem. Serenelli describes how it was “refurbished with its reassembled ‘original’ furniture … (Mussolini’s only criticism was that the mattresses on the beds should have their wool stuffing replaced with more humble corn leaves),” and how, before the visit to Predappio of King Victor Emmanuel in 1938, Mussolini “ordered the removal of the huge arch over the access steps to the casa natale [birth house] from the market square below” because he considered it excessively ornate (ibid.: 97; see also Balzani Reference Balzani1998).

In other words, much of the specific role Predappio had to play in the creation of the myth of Mussolini highlighted his humble, ordinary origins and proletarian, anti-bourgeois characteristics, and Italians were encouraged to see these—literally, by coming to Predappio to look at the corn leaves in his bed—as part of his exemplary nature. This is clearly not an “original,” “independent” ordinariness—it is constructed, just as New Predappio was constructed as both the paradigmatically ordinary Apennine village home of Italy’s humble Duce and a “cathedral in the desert” (Serenelli Reference Serenelli, Gundle, Duggan and Pieri2013: 99), a spectacular monument to one man and to Fascist urban planning.

In this historical case, a sense of ordinariness is created that is both substantive and relational: on one hand, both Predappio and Mussolini are ordinary in the sense that they typify something more general than themselves: rural Italy, a peasant upbringing, and so forth. Yet their ordinary exemplarity is also relational, opposed to both the Italian urban liberal bourgeoisie and their own future temporality: to Predappio Nuova, the paese del Duce, and to Mussolini, the “man of providence.” Predappio’s status as exemplary of both ordinariness and extraordinariness remains striking today albeit in different ways, and it is to contemporary exemplars of the ordinary that I now turn.

The “Toxic Waste Dump” of History

Predappio was liberated by a Polish regiment fighting with the Allies on the 28th of October 1944 (ironically, also the anniversary of the Fascist “March on Rome”). Writing nine years later, fascist sympathizer Vittore Querel described it as “the poorest and most abandoned, the saddest and most wretched town in all Italy” (Bosworth Reference Bosworth2002: 338; Luzzatto Reference Luzzatto2014: 174). The Caproni airplane factory closed, and a great many jobs went with it. The flow of tourists dried up, and the comune’s population dropped from a peak of around eleven thousand down to its current levels of about six thousand. According to one local historian, however, archival reports from the local carabinieri suggest that already by 1946 flowers and other offerings were being left at the tomb of Mussolini’s parents in the cemetery of San Cassiano (M. Proli personal communication, 2017).

Then, in 1957, Adone Zoli of the dominant center-right Christian Democrats became Italy’s Prime Minister. He led a minority government which, it soon became clear, would for the first time have to rely on a “confidence and supply” agreement with the new incarnation of Italy’s Fascist Party, then called the Italian Social Movement (MSI). He also happened to be another native of Predappio, his family owning the estate on which Mussolini’s wife had been born. Though it would last little more than a year, one aspect of the agreement with the MSI was that Mussolini’s body—at that time hidden in a Capuchin convent—would be returned to the Mussolini family and interred in their crypt. Zoli is alleged to have telephoned the then mayor of Predappio to ask for his blessing. The response he received—constantly quoted by Predappiesi today—was, apparently: “Mussolini didn’t scare us when he was alive, and he won’t scare us now that he’s dead.”

The body was reburied in the cemetery of San Cassiano in Predappio on 31 August 1957. Accompanying it were 3,500 neofascists, and the very next weekend seven thousand more turned up to pay their respects. When told by the police that they were not allowed to wear fascist shirts they simply took them off, resulting in a cemetery full of semi-clothed men (Luzzatto Reference Luzzatto2014: 212–13). Since then, the town has tended to attract from around eighty thousand to one hundred thousand “black” tourists a year. There are three particular days that involve commemorative marches, speeches, and festivities: the anniversaries of Mussolini’s birth and death, and the anniversary of the March on Rome. Mussolini may or may not scare Predappiesi since his death, but he has certainly had a very profound effect on their lives.

Serenelli’s characterization of Predappio as a “cathedral in the desert” is highly apt. In its appearance it is strikingly distinct from all its surrounding neighbors in a manner that is impossible for the visitor not to notice, and obviously its inhabitants are highly cognizant of this distinction. Nearby villages are divided up by windy, cobbled lanes that make them hard to navigate for outsiders, while Predappio is built on a grid plan with wide, tarmacked avenues; most towns in the area, as in nearby Tuscany, are built of stone, while much of Predappio is made of marble, brick, or concrete.

Architecturally speaking, Predappio is still utterly dominated by the style of the ventennio (the twenty years under Fascism). The main square is overlooked by the imposing church of St Anthony, on whose façade is inscribed the date of completion in the “E. F.” or “Era Fascista.” The old hospital on its right-hand side still has a fasces—the symbol of the regime—embedded in one of two decorative orifices. Across the square is the former Casa del Fascio, topped by a monumental bell tower, and now desolate and in ruins (see image 3). The mayor sits at Mussolini’s old writing desk, salvaged from the nearby Rocca delle Caminate, while Mussolini’s summer residence looks over the town from its perch on a nearby hill.

Image 3. The abandoned Fascist Party Headquarters building on the day of an anniversary march. Author’s photo.

A walk in one direction down the former Corso Benito Mussolini—now renamed after the most famous victim of Fascism, Giacomo Matteotti—will lead you past three shops that sell what are euphemistically referred to as “souvenirs”: T-shirts and babies’ bibs with fascist slogans printed on them (“me ne frega”) or images of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, copies of Mein Kampf and busts of Mussolini, war medals, and even manganelli, the clubs with which Fascist squads would beat their opponents. One vendor insists that they will break if you try to hit anything (or anyone) with them. Across the street from the house in which Mussolini was born (now an exhibition space) is the osteria, which dates to the time of Dovia, in which one can purchase bottles of wine with Mussolini’s face printed on the labels.

Leaving the main square in the opposite direction will eventually take you to the cemetery of San Cassiano, which houses the remains of family members for many contemporary Predappiesi, as well as those of the Mussolini family. It is for the latter reason that one is likely to be asked for directions to it by visitors, however, and it is the Mussolini crypt that is the first thing one sees upon entering the cemetery, at the end of the path which begins at the cemetery gates. Descending a flight of stone stairs one emerges in a small subterranean chamber, in which the remains of Mussolini’s wife, children, and some affines are entombed in stone sarcophagi, in a number of cases topped by marble busts or photographs. In the center is a large bust of Mussolini himself, gazing out over a visitors’ book in which are inscribed—by my average count—thirty to forty new messages a day, most of which are variations on a theme of “come back to us Duce!” (see also Zoli and Moressa Reference Zoli and Moressa2007). Passing through the crypt and ascending by another staircase, one is faced with several walls covered almost entirely in plaques donated by neofascist organizations—formal or informal—commemorating a visit to the tomb, or the passing of a comrade. For its black-shirted visitors, Predappio is symbolic of a history Italy should remember with pride—“those who don’t respect the past cannot govern the present,” reads one large banner at an anniversary march I witnessed (see image 4).

Image 4. Marchers in fascist uniform before an October parade. Author’s photo.

It is not only Predappio’s architecture that marks it out as distinct: its very existence depends on its relationship to Mussolini, and both locals and outsiders are very aware of this fact. The first results returned in a Google image search for Predappio are pictures of men and women marching in black shirts through its streets, and Tripadvisor.com’s number one site recommendation is the cemetery in which Mussolini is buried (354 reviews, mostly five star). Every year, on the occasion of the fascist anniversaries, national and international newspapers splash across their pages images of black-shirted marchers striding through the town, or of one of the three “souvenir” shops that exist in the town to sell Mussolini-related paraphernalia to tourists. If outsiders are aware of the existence of Predappio, it is invariably because of this association with Fascism. Indeed, many Predappiesi have told me that they would often lie to outsiders when asked about their origins to save themselves from either embarrassment in the face of those on the left, or unwanted offers of friendship and fellowship from those on the right. To many Italians on the left, Predappio is a “toxic waste dump,” in the words of one notable commentator (Wu Ming Reference Ming2018). To many on the right, it is exemplary of a history worth remembering and valuing, the “paese del Duce,” and such is what they claim when they come to march on anniversary days.

Unlike their town’s visitors, contemporary Predappiesi spend very little time talking about Mussolini. Aside from the special case of the “souvenir” shops (most of which are not owned by locals), images or mention of him are hard to find in public discourse in the town. One or two small street signs point the way to the casa natale, but until recently it was an empty exhibition space. Nothing advertises the location of the family crypt, which is why one is very likely to be stopped on the street to be asked for directions to it by visiting tourists. The only person in town who regularly talks of Mussolini is the mayor, and that is, as the last incumbent of this position was wont to point out to me, because he is obligated to do so as the public face of “extraordinary” Predappio, the man to whom the news networks and journalists go for a quotation. When Mussolini does appear in public discourse—as in a temporary exhibition at the casa natale—it is “young Mussolini” who appears, the ordinary, “humble” (and socialist) Mussolini, rather than his later incarnations.

This perspective on Mussolini also appears in local historical narratives of the town. Much is made of the strong republican, socialist, and anticlerical tradition of the region, and Mussolini’s own father is frequently cited as exemplary of this tradition, as an erstwhile socialist member of Predappio’s town council. “He would be spinning in his grave if he could see who comes to visit it,” is the sort of sentiment one hears from Predappiesi about Mussolini padre. Whereas, for obvious reasons, the regime tended to downplay Alessandro’s significance, making use only of his “ordinary” status as a blacksmith.

But while Alessandro Mussolini’s politics are sometimes the subject of comment, it is not straightforwardly the case that local narratives pit an exemplary “socialist” Predappio against an exemplary “Fascist” one. Instead, it is Predappio as an ordinary, everyday place, and ordinary, everyday Predappiesi, that appear as counterparts to Predappio, “paese del Duce.”

“The White Poplar’s Leaf”

This is the case even though an alternatively politicized, socialist vision of Predappio is very much available to locals. Their town is in the heart of the Italian “red belt,” the most left-wing region of Italy. The town itself and its surrounding areas has an older tradition of socialism and republicanism than it does of Fascism, and as I say, both Mussolini and his father were prominent socialists when they actually lived in the region. Until the last mayoral elections, every postwar mayor of the town has been from the Italian Communist Party or one of its direct descendants.

In practical terms, there are also means by which Predappiesi could, if they wished, demonstrate their allegiance to this sort of narrative about their home. For example, the 28th of October is the anniversary of Mussolini’s “march on Rome,” and it is the largest of the three marching days for the pilgrims who come to Predappio. But it is also, by coincidence, the anniversary of Predappio’s liberation from the Nazis by Allied troops and partisans in 1944. In recent years, the National Association of Italian Partisans (ANPI, a powerful political lobby group in Italy) has taken to sending a delegation to Predappio to mark this anniversary with partisan music and song and a celebratory dinner. This is explicitly framed by the organizers as a response to the neofascist marches, and the speeches at such events invariably emphasize “taking back” Predappio from its modern-day fascist “occupiers,” and rescuing its inhabitants from the sad fate that has befallen them. I have been attending these events for three years, and the only locals usually present are a small group of town councilors who come out of a sense of obligation, and who spend most of the evening complaining quietly amongst themselves about outsiders who come and try to tell them how to run their home. “These people are like colonialists,” one whispered to me on one occasion, “they drop in once a year to lecture us about democracy and then they go home, but they have no idea what it means to live with this history on a daily basis.” A more common response to these events from Predappiesi was simply a circumspect shrug, and the assertion that the 28th of October was a day like any other, and people have other things to do than sing partisan songs or march around in silly uniforms.

Local narratives of the history of the town also tend to downplay Fascism and Mussolini. But, as in the above case, they do not do so in order to promote an alternative, socialist history of Predappio, but rather to focus on the hardships of war and the postwar period. An example of a local historical narrative that, unusually, explicitly sets out to treat Fascism in Predappio, is a collection of oral histories and narration published by three local residents (Capacci, Pasini, and Giunchi Reference Capacci, Pasini and Giunchi2014). The book is titled La fója de farfaraz, dialect for “The white poplar’s leaf,” which is alleged to change color according to the direction of the wind. The expression is used to denote a person who is similarly prone to change their allegiances depending on convenience, and the book itself is filled with descriptions of “voltagabbana,” or turncoats, who switched sides from socialist to Fascist in the interwar period, and sometimes back again afterward. Yet it is an affectionate rendering of the town’s history and treats this characteristic changeability not as a moral failing but as a kind of virtue.

For instance, it helps to depoliticize the extent to which Fascism permeated Predappio under the regime: “For reasons of economic benefit and for those of social and political control, everything should make one think that Predappio must have been the most Fascist place in Italy … the real surprise is that it was not.” Adherence to Fascism in Predappio did not, according to this narrative, stem from “political debates or ideology, but from normal citizens’ adjustment to the new regime. So, unlike in other areas, Fascism did not produce deep longstanding personal hatred” (ibid.: 55; all translations my own). On local Fascists, it claims that “local anti-Fascists agree that even the most visible Fascists in Predappio did not behave badly, all things considered. Some even behaved rather well considering their role … the cases of really hated Fascists are very few and are those who were informers. In such cases the odium is severe, because to political sins are added the betrayal of one’s own community, one’s own people” (ibid.: 53). As in the opening vignette from Passerini, here a division is drawn between “the ordinary” and the “political,” and while purely political crimes may be forgiven, those which cross the line into “the ordinary” cannot: “betraying one’s own community” is a more serious crime than the “political sin” of being a Fascist.

Later, discussing the cult of personality surrounding Mussolini, the book turns the standard narrative of Predappio, paese del Duce, on its head: “We believe that Fascists from the Romagna had to work particularly hard [at developing and sustaining the personality cult] because our region was not one of those in which Fascism found a natural home. They would have liked it to be an exemplar, but it never was … so it was necessary for them to valorize the only positive trait it had: the fact of being the terra del Duce.” In this narrative, Predappio becomes an unwilling exemplar partly by virtue of the accident of history by which Mussolini was born there, and partly because of its recalcitrantly non-Fascist nature (though not necessarily anti-Fascist, as the writers concede).

One striking aspect of the book is that much of it is devoted to an alternative hagiography of a local exemplar rather different to Mussolini, someone about whom Predappiesi speak much more often and more freely. Giuseppe Ferlini has the distinction of being the most notable partisan from Predappio (although there are other less famous instances). He was the commander of the partisan forces that liberated the town in October 1944, together with Allied troops (see image 5).

Image 5. Giuseppe Ferlini. Reproduced with kind permission of Nicoletta and Jara Valgiusti.

Like Mussolini’s father, Ferlini is very much available as a politicized exemplar, the communist equivalent to Mussolini. He came from a socialist family and became Predappio’s first communist mayor after its liberation, serving for a year before elections were held. As in the case of Predappio’s socialist heritage, or ANPI’s visits on the 28th of October, it would be easy to read local affection for Ferlini as an alternative politicization of Predappio, one from the left instead of the right, a hero and exemplar not for Fascists but for communists.

However, what is striking about Ferlini’s exemplary status is that it stems from more than just his military and political abilities and appeals across the political spectrum. Many Predappiesi with conservative and right-wing backgrounds happily declare Ferlini to be Predappio’s most meritorious son. They cite in evidence not his politics or his service in the partisans but his simplicity, humility, and lack of ideological fervor. They tell a range of stories of him. One favorite—also recounted in the local history book I have cited—involves him falling over while visiting Milanese notables in their palace, as his shoes were too poorly made to keep him upright on the slippery marble. Another favorite Predappiesi story about Ferlini is that after his retirement from political office he was often to be found on his knees washing the stone steps leading to the town hall. He is alleged by many to have retired from politics simply because he wished to return to being an ordinary citizen.

Moreover, his pragmatism and lack of ideological fervor are credited by many with keeping the peace in postwar Predappio. Stories are told of him rescuing arrested Fascists from execution, and of involving the former podestà (Fascist mayor) in civic business, and it is even said that another reason for his retirement from politics may have been disagreements with more senior communist figures in the region over his benevolence toward defeated servants of the regime. There is no such disagreement over his legacy today, and he remains an acclaimed figure on both the right and the left. Such acclamation focuses largely not on his actions as a partisan leader, but on his imputed ordinariness. Focused on this ordinariness, La fója de farfaraz comes to appear like a sort of inverted version of the De Casibus tradition’s use of the lives of famous men to illustrate a general moral principle.

In contrast to their reticence regarding Mussolini, Predappiesi enjoy recounting their own stories of Ferlini’s ordinariness. For example, Sergio, an acquaintance of mine in Predappio, was a very elderly man whose family ran a longstanding local business (unrelated to the souvenir trade). He was known in the town for his history in far-right politics, having been the founder of the local chapter of the Movimento Sociale Italiano (the immediate successor of the Fascist Party). He had also been a prisoner of war in the United States and had pointedly refused to take an oath to the King when Mussolini was deposed in 1943. Yet Sergio’s admiration for Ferlini, whom he had known personally and who had fought against his Fascist compatriots, was clear when we spoke of him: “He was a good guy, a good man, an honest man, honest indeed.” Sergio, despite his politics, kept his own collection of local partisan songs dedicated to Ferlini, and he, like other Predappiesi, also delighted in telling stories of Ferlini’s pragmatism:

One day, after the war and after he was ousted as Mayor, I was sitting there, and he called me. He says to me [in local dialect], “Sergio, come here, I want to tell you something—I’ve been to visit your friends!”

So I say, “My friends? Who are my friends?”

“Fascists, like you! I’m just coming back from there, I went to see them this morning.”

So, who were these guys? They were Repubblichini [soldiers of Mussolini’s post-1943 regime, the Italian Social Republic] and in the war they controlled the nearby mill, and the food that local people could access. So Ferlini had a deal with them to get food for people. He told me, “My problem was not fighting. They told you I fought against you and I freed Predappio, et cetera, but really my problem was to give food to people who needed it. So with the help of the priest and these guards, we brought flour to the town from the mill.”

This narrative is typical of many that one hears in Predappio from people on both the right and the left, as well as from the majority who do not identify very strongly with either. Ferlini is lauded in such stories not for his military valor or for his status as the liberator of Predappio, but for his down-to-earth qualities (note Sergio speaks in dialect when giving him voice), his pragmatism (feeding people is more important than fighting Fascism), and his disregard of ideology (after the war he still visits the Fascists who used to guard the mill and give him access to flour). All these qualities are also those which most Predappiesi like to see in themselves and are the opposite of those that the rest of the country sees in them when it sees the inhabitants of the birthplace of Benito Mussolini.

Unlike the careful management of the image of Mussolini’s humble roots by the Fascist regime, stories of Ferlini are not generally directed at a wider public. Almost nobody outside of the town will have heard of Giuseppe Ferlini, and indeed there is nothing in these stories of him that would make him of any serious relevance or interest to anyone outside Predappio. Precisely their point is that he was, all told, a thoroughly ordinary man. Rather than being exhibitions of ordinariness in the service of a broader political narrative then, these are, to paraphrase Geertz, stories Predappiesi tell themselves about how they would like to be.

Cultivating Ordinariness in “Ordinary Life”

Contemporary Predappio remains the “cathedral in the desert” that it was during the ventennio. It is marked out as special and extraordinary in relation to the surrounding area—and indeed to any ordinary Italian town—by a range of factors, most obviously its architecture, urban environment, history, and by the crowds of black-shirted tourists who parade through it. All of this comes down, in the end, to Predappio’s relationship to one man, its most famous native son.

In the first section of this paper, I argued that despite its extraordinary status, ordinariness was an important dimension of Predappio’s exemplarity under the Fascist regime: Mussolini’s putatively ordinary origins helped frame both him as an exemplary leader and Predappio as one of the jewels in the crown of Fascist urban engineering. While vestiges of this interest in ordinary Mussolini remain today—for instance in the focus on “young Mussolini,” when he appears in public discourse—for the most part, “ordinariness” has shifted in meaning and focus. What had made Predappio a positive exemplar under the regime is now what makes it a negative exemplar to many outsiders. Its spectacular appearance and extraordinary heritage are now deeply problematic, symptoms of Italy’s “difficult heritage” (Macdonald Reference Macdonald2009a), not objects of pride. It is this “extraordinariness” that is now the backdrop to “the ordinary” that Predappiesi reach for in contrast to it: stories of Ferlini’s pragmatism, poverty, and humility do not serve to set the stage for greatness; instead, they serve to scale the town down and away from grand ideological and historical narratives that focus on Predappio’s relationship to Mussolini. They do, in short, exactly what many historical and anthropological arguments about “the ordinary” and “the everyday” do. They concretize ordinariness in particular phenomena—nepotism, petty crime, marital disputes—or in figures such as Ferlini, so as to set them against some putatively “larger” class of phenomena—politics, ideology, great men, transcendence—or figures such as Mussolini.

Ferlini, by contrast to Mussolini, is thought to be ordinary because he is humble, he is pragmatic, because he lacks political ambition, because he washes the town staircase. But the reason he is exemplary is that these are anything but ordinary (in the sense of “typical”) characteristics in Predappio, in which ordinariness itself has come to take on a special salience. Predappio’s entire existence depends on its original mythical status as the ordinary town in which “humble” Mussolini was born, yet that same fact now marks its existence as quite “extraordinary”: it is a Fascist “cathedral” in a desert of medieval architecture, an island of black in the political sea of Romagnole red, and its inhabitants are habituated to outsiders defining them almost entirely with reference to the high politics and ideology of debates around fascism, for good or for ill. In an “extraordinary” place, whose very urban fabric seems to demand that one take a position on fascism, being thoroughly ordinary may itself be seen as extraordinary, and indeed exemplary for this reason. Ferlini is not exemplary despite his ordinariness, but because of it.

This treatment of Ferlini as an ordinary exemplar is in line with the attitude Predappiesi tend to adopt more generally towards their home and its contested status in the landscape of Italian history and heritage. The architecture and urban environment of the town is a similar case: there have been a range of debates over what to do with various significant Fascist buildings, including the Rocca delle Caminate and the former Fascist Party headquarters, debates which replicate those taking place on a national scale (see e.g., Malone Reference Malone2017). Often in Predappio the victors in such local debates are not projects aimed at narrating the historical importance of such buildings, nor those which seek to emphasize an alternative, anti-Fascist Predappio. They are those which put such buildings to banal, ordinary uses. The Rocca, for example, after a recent restoration project, is presently a venue for meetings and conferences, and plays host to several small regional technology companies. Almost the only reference to its history is a small and difficult to locate plaque near to what used to be the barracks of a Fascist militia unit, commemorating the partisans killed there. This is not anti-Fascist banalization of the sort that Sharon MacDonald describes as a conscious and explicit political strategy in contemporary Nuremberg, aimed at undermining Nazi architects’ visions of the glorious ruination of their buildings (Reference Macdonald2009b). If there is an aim to this treatment of architecture it is not to contest Fascist historical narratives, but to sidestep them inconspicuously as far as is possible.

The former party headquarters building is a rather special case. In line with this sidestepping of historical narrative, it has lain largely empty and in ruins since the end of the war, even though it dominates Predappio’s main square (Storchi Reference Storchi2019). Again, almost nothing marks its historical status, with the exception of another, lately added, small plaque on the building’s outside. However, it has recently come to contribute to Predappio’s international reputation, as plans were made to transform it into a sort of museum or documentation center on fascism. These plans have caused significant local and national controversy, however, since the plans for the content of the center are alleged by prominent critics to depoliticize Fascism and treat it as a neutral historical phenomenon (e.g., Fondazione Alfred Lewin 2016; Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg2016; Levis Sullam Reference Levis Sullam2016; Wu Ming Reference Ming2018). Moreover, even though over the course of my fieldwork in the town it is the plans for this center that have put Predappio back in the glare of international publicity, Predappiesi themselves have paid little attention to this new attempt to capitalize on their heritage. This is not because they are uninterested in political questions: at one point in the course of 2018 a substantial group of citizens became so agitated over a proposal to introduce a new recycling system that a violent altercation nearly broke out in a town council meeting. It is not politics in itself that they avoid, but the high politics of Fascism and its aftermath.

I have described the similar approach Predappiesi take to the black-shirted marchers who visit their town earlier in this paper and elsewhere (Heywood Reference Heywood2019). Again, there is no coordinated attempt to contest their presence, though legal instruments exist through which they could do so. Instead, the predominant local narrative about the marches is that they are a form of absurd nostalgia, akin to the carnivals that take place in other towns. Locals will complain about the marchers as an impediment to traffic, but nothing more; and while in the past, during the political tensions of the 1960s and 1970s, they might well have stayed inside with the doors locked on the anniversary days, today they will bustle through the crowds to do their shopping, interrupt neofascist singing in a bar to order their morning coffees, and stroll into the cemetery to tend the graves of relatives as marchers make their way to the Mussolini family crypt. In other words, the virtues of ordinariness exemplified by Ferlini are virtues many Predappiesi seek to exhibit in relation to their Fascist history. They neither celebrate this history, nor confront it, but rather ostentatiously pursue their ordinary lives around it, as if with the image of an ex-Mayor washing his town’s staircase in their minds.

Despite this widespread public disavowal of interest in Mussolini and his afterlife, in some senses and in some cases, we can see a sort of “cultural intimacy” (Herzfeld Reference Herzfeld2016[1997]) at work in Predappiesi attitudes to their most famous son. As I describe below, many Predappiesi have stories of personal encounters between Mussolini and their parents or grandparents, and they tell these—in private homes or in lowered tones in public amongst friends—with a degree of pride at their proximity to a man who shaped globally significant events. But there are rarely any nudges or winks here (ibid.: 6). Although some few on the extreme right, like Sergio, may feel pride in identification with the man himself, any sense most Predappiesi have of being held together by their unique relationship to Mussolini does not usually come with any form of identification with him. For the most part what is culturally intimate here is simply open acknowledgment of their home’s history, an acknowledgment most will usually make with only the greatest of reluctance to outsiders—as I have mentioned, many Predappiesi have tended to lie to outsiders about even the fact of being from Predappio. Neither, as we have seen, can stories of Ferlini’s ordinariness be understood as a performance for outsiders, given that most outsiders to Predappio have no idea who he was and that most of them are of course far more interested in Predappio’s much more famous historical product.

Most Predappiesi take no public pride in their town’s status as the birthplace of il Duce. Neither, however, do they contest this status, for example by inhabiting the opposite pole of political exemplarity: they do not trumpet their socialist heritage any more than they do their Fascist heritage. Instead, for the most part, they deal with this extraordinary heritage, and their equally extraordinary place in the Italian popular imaginary, by scaling themselves down, and out of history, in all the ways that they can. Ordinariness, as exemplified by Ferlini, is a prized virtue in this context.

Conclusion

The main claim I have made in this paper is that ordinariness and everydayness are not “original” or “independent” attributes or domains but require work to construct and sustain. More specifically, I have pointed to one form that this kind of ethical work might take, namely that of exemplification. The notion of exemplarity has been helpful to anthropologists in showing how particular values and virtues are concretized and instantiated in specific individuals, and thus rendered tangible (e.g., Humphrey Reference Humphrey and Howell1997; Robbins Reference Robbins, Laidlaw, Bodenhorn and Holbraad2018). In my account, however, what takes the place of a virtue like leadership, strength, or generosity is ordinariness, something we are more wont to think of as a given property of something or someone. Indeed, as I pointed out in my introduction, there is something unlikely about the category of the “ordinary exemplar,” in that one might well assume that ordinariness should require no exemplification.

I have argued, however, that it does, and sought to describe two different instances in relation to Italian Fascism in which the ordinary and the exemplary have intersected. In the first, more straightforward, case, both Mussolini’s putatively ordinary peasant upbringing and Predappio as an ordinary Italian town served to frame the work done by the regime to turn both into quite extraordinary objects of attention. Mussolini, of course, became il Duce, the object of a cult of personality. Predappio, meanwhile, was transubstantiated into “Predappio Nuova,” the paese del Duce, rebuilt as a monument to Mussolini and to the regime’s modernity.

In this first, historical case, Mussolini’s ordinariness was defined by its generic and retrospective nature. His upbringing exemplified the “ordinary” in the sense of a general, typical, type: “rural,” “impoverished,” “working-class,” et cetera. His “ordinariness” in this sense is quite distinct from his future exemplarity as a cult figure: his ordinariness is the background against which his status as l’uomo della providenza emerges, rather than the cause of it. An interesting consequent question is how distinctively “fascist” is this conjunction of “greatness” and ordinariness, in which the leader is both special and exemplary, but also average and typical.

In contemporary Predappio, however, things are somewhat different. It is impossible for locals or outsiders to take any putative ordinariness about Predappio for granted. Its place in the popular imaginary is completely founded upon its extraordinary status as the place of Mussolini’s birth and the site of his tomb, and this is constantly reinforced by its appearances in popular culture, in the press, and on television, which all tie it to this status, as do interactions Predappiesi have with outsiders, who make assumptions about them on the same basis. In this context, a sense of ordinariness takes a great deal of work to construct and sustain, and I would contend, with Sacks (Reference Sacks, Atkinson and Heritage1985), that it will take some degree of work in any context—that there is no scale of ordinariness that exists independently.

In Predappio, one form that work takes is exemplification through the figure of Ferlini. Unlike in the historical case of Mussolini, it is precisely Ferlini’s ordinariness that makes him exemplary. Here, ordinariness is a concrete value: it is not that Ferlini is exemplary because he “stands for” or is typical of some set of other things, but because—like Humphrey’s Mongolian exemplars—he is taken to exhibit certain specific (and unusual) characteristics of ordinariness that can be drawn on by those around him, used to concretize the idea that their home—despite its history, its architecture, and its place in contemporary political polemics—is really just another ordinary Italian town, filled with ordinary Italian people. He is, in a sense, a “scaling-device” (Summerson Carr and Lempert Reference Summerson Carr and Lempert2016), whom Predappiesi can deploy to scale their home and themselves “down” into “the everyday,” and out of the grand historical narratives of Fascism into which they have been unwillingly enmeshed.

One question that remains to be addressed is the precise nature of the relationship between these two variations. Is it the case, for example, that the ordinariness for which contemporary Predappiesi strive is the same ordinariness that the Fascist regime sought to conjure up in its propaganda? Does the former have its origins in the latter?

In some ways the answer to this latter question is “yes,” even though the answer to the former is “no.” The aura of ordinariness Mussolini tried to create around himself through Predappio was not one that was likely to take in Predappiesi themselves, who of course had an intimate (one might say ordinary) knowledge of their socialist-turned-Fascist compatriot.

“Historic turncoat number one in Predappio was Benito Mussolini, the Duce of Fascism, son of Alessandro Mussolini, anarchist socialist, and blacksmith of Dovia,” note the authors of La fója de farfaraz (Capacci, Pasini, and Giunchi Reference Capacci, Pasini and Giunchi2014: 212). Many in the cheering crowds in Piazza Cavour on the occasion of Mussolini’s 1923 visit, and the regular subsequent visits, would have known him personally. They would have remembered him as the firebrand socialist of his youth. They would also have known that he had had many of his old comrades from the left in the town arrested in advance of the visit so that they would not cause him any inconvenience. So, the “ordinary Mussolini” conjured up in Fascist propaganda did not just mean, to Predappiesi, proletarian, rural, anti-bourgeois, et cetera: he was also the first, and the greatest, of the turncoats who fill so many narratives of these years, and for whom La fója de farfaraz is entitled.

La fója de farfaraz contains a number of stories of locals making their feelings on this subject clear to Mussolini himself. They may or may not be apocryphal, but they illustrate the sense of intimacy with “ordinary Mussolini” to which Predappiesi feel they are entitled. In one story, Mussolini stops a local character, while visiting the town, whom he recognizes from his days in the socialist party to ask him what he thinks of the national political situation, and the man replies (in dialect), that he has never liked the white poplar leaf (“La fója de farfaraz”) and turns away (ibid.: 203). In another story, Mussolini, when he was a socialist, baptizes the son of a friend with the un-Christian name of “Rebel.” After the Lateran Pact with the Catholic Church, Mussolini tells the child’s father he must change his son’s name, and the father replies that since, after all, Mussolini gave him the first name, he’d better be the one to change it (ibid.: 214).

What these stories point to are not Mussolini’s failings as a socialist. They index a characteristic of Mussolini’s ordinariness that distinguishes him for Predappiesi from the unmarked ordinariness of Ferlini. Mussolini’s ordinariness is a deliberate, cultivated stance. Whereas Ferlini is simply, as La fója de farfaraz puts it, “a practical man of good sense” (ibid.: 145). He has no “theory” of ordinariness, he is simply ordinary. He is not, as it were, a “pragmatist,” he is just pragmatic. His ordinariness is described in a manner that leaves it unstudied; natural, rather than cultivated.

This, I would assert, is another reason why Ferlini is so easily cast as exemplary in contemporary Predappio: his ordinariness, unlike Mussolini’s propagandized ordinariness, and unlike the fragile semblance of “ordinary life” which contemporary Predappiesi reach for through him in studied and deliberate fashion, seems to take no work.

This is distinct from both the self-conscious work Mussolini and early Fascists had to do, and the self-conscious work many contemporary Predappiesi do, to pursue the form of ordinary life itself, in which the quality of ordinariness itself is at stake. In other words, and ironically, the very fact that Predappiesi require Ferlini as an exemplar of ordinariness is indicative of the chasm that separates him and them.

So, the kind of ordinariness at stake in Fascist visions of Mussolini and his hometown is a very different kind from that which contemporary Predappiesi reach for through Ferlini. Yet it is precisely in this need to “work” for a sense of the ordinary that the two kinds of projects resemble one another, and part of the reason contemporary Predappiesi need to do this work, and require exemplars of ordinariness, is because of the work Mussolini put into transforming Predappio, first into an exemplar of an ordinary Italian town, and then into a Fascist cathedral in a desert of medieval architecture and socialist politics.

In our own analytical usage, notions of ordinariness and everydayness are ambiguous. On the one hand, for instance, scholarly writing on “everyday Mussolinism” takes it to be commonplace, because it involves specific sorts of phenomena like sex, petty criminality, or nepotism that are in some sense thought to be “typical” of some basic human activities. On the other hand, “the ordinary” and “the everyday” are also relational, formal categories, exemplary and special insofar as they are not something else: they are opposed to the domain of high politics, and to ideology, or transcendence, for instance. We can see this ambivalence at work in the portability of the concept: behind “everyday Stalinism” and “everyday Mussolinism” is the same imputed everydayness: domesticity, low-level crime, friendship, food, and so forth. But at the same time such everyday activities are thought to be everyday precisely insofar as they are opposed to “larger-scale,” “macro” phenomena such as social structures or great men’s biographies. “Everyday Stalinism” and “Everyday Mussolinism” are “typical” in relation to one another, but “exemplary” in relation to the respective totalitarian contexts in which they exist.

As in the case of contemporary Predappio, I am suggesting, analytical usage of “the ordinary” has the effect of transforming the phenomena to which it is applied into exemplars, rendered distinctive by their opposition to some other class of phenomena. They help to scale a level of an analysis in relation to other such levels (so we “descend” into the ordinary from the “heights” of reason, law, or transcendence). But there is nothing in such levels themselves to provide them with scale, or exemplarity. There is no reason why doing the washing up, or eating, walking, or sleeping should be ordinary in and of themselves (Cook Reference Cookn.d.; Laidlaw and Mair Reference Laidlaw and Mair2019), or why eating lightbulbs should be extraordinary in and of itself (Clarke Reference Clarke2014).

As I have sought to illustrate in this paper, leaving this unrecognized risks missing the fact that we as analysts are not the only ones who engage in this process of “ordinarification” via exemplars. Predappiesi do so in an attempt to escape from the apparently intractable grasp the history of their home holds over them. So too, in different ways, do populist politicians, as illustrated by the historical case of Mussolini’s “ordinarification” by his regime (see also Langhammer Reference Langhammer2018 for an insightful analysis of a similar process in postwar Britain). It will be easier for us to examine such instances if, instead of treating “the ordinary” and “the everyday” as if they qualify anything about the phenomena to which they are attached, we look instead at what the phenomena in question reveal about what we and the people we study really mean by “ordinariness,” and how we and they create our sense of it. “The ordinary,” in other words, may be the object of ethical labour, rather than its site.