Health care and social services practitioners providing care to older adults who are mistreated in their homes by family caregivers play a crucial role in ensuring quality care and quality of life for these clients (Anetzberger, Reference Anetzberger and Anetzberger2005). A dementia diagnosis further complicates these cases (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2010a) and may contribute to the hidden nature of mistreatment (Selwood, Cooper, & Livingston, Reference Selwood, Cooper and Livingston2007). Previous research has shown that older adult mistreatment (OAM), without intervention by the practitioners who can access the home, can result in a worsening of health if not a hastening of death (Ortmann, Fechner, Bajanowski, & Brinkmann, Reference Ortmann, Fechner, Bajanowski and Brinkmann2001). However, practitioners’ disempowerment in OAM cases has been reported in various socio-legal and political contexts (Beaulieu & Leclerc, Reference Beaulieu and Leclerc2006; Omote, Saeki, & Sakai, Reference Omote, Saeki and Sakai2007; Wilson, Reference Wilson2002). Further impacting this experience are contextual influences stemming from the health care and social services institutions, the geographical environment, and the socio-political contexts which dictate societal and legal expectations with OAM (Bergeron, Reference Bergeron1999; Erlingsson, Carlson, & Saveman, Reference Erlingsson, Carlson and Saveman2006; Lithwick, Beaulieu, Gravel, & Straka, Reference Lithwick, Beaulieu, Gravel and Straka1999). Understanding the professional agency of practitioners, their ability to control outcomes and act in a meaningful way (Frie, Reference Frie2011), and the contextual influences that are required to support them in this work, are essential, as both the experience and the contexts ultimately influence case outcomes for mistreated older adults.

To address this issue, the first author undertook a critical inquiry underpinned by Critical social theory (Habermas, Reference Habermas and Shapiro1971, Reference Habermas and McCarthy1976, Reference Habermas and McCarthey1984), and the concepts of critical consciousness (Freire, Reference Freire1972), and professional agency (Frie, Reference Frie2011). The study aimed to understand how health care and social service practitioners experience professional agency when encountering mistreatment of older adults with dementia perpetrated by a family caregiver; explain how health care, socio-political, and geographical contexts influence the experience; and encourage practitioners to critically reflect on this reality, a first step to empowerment and improving practice, policy, and outcomes. Findings pertaining to the two first aims reveal a distressing experience, and within oppressive contexts, are foundational to this article and have been described in two other articles (Lindenbach, Larocque, Morgan, & Jacklin, Reference Lindenbach, Larocque, Morgan and Jacklin2019; Lindenbach, Morgan, Larocque, & Jacklin, Reference Lindenbach, Morgan, Larocque and Jacklin2020). This article focuses on the important issue of the need for empowerment and reports, from the perspective of practitioner participants, on specific barriers to performing their role in OAM management within the care context of dementia cases in Northeastern Ontario. Participants also proposed action projects to address these barriers which are described elsewhere (Lindenbach, Reference Lindenbach2019).

Background

OAM is defined as “actions and/or behaviours, or lack (thereof), that cause harm or risk of harm within a trusting relationship” (McDonald, Reference McDonald2015, p. 6). This definition mirrors the focus of this study: OAM cases occurring, either in the form of abuse or neglect, between the family caregiver/older adult with dementia, within the home, where there is a societal expectation of trust, but where this trust sometimes results in abuses of power and control (Choi & Mayer, Reference Choi and Mayer2000; Lowenstein, Reference Lowenstein2010). The negative impacts of OAM can be far reaching, including a downward spiral of isolation, increased morbidity, and mortality (Lachs, Williams, O’Brien, Pillemer, & Charlson, Reference Lachs, Williams, O’Brien, Pillemer and Charlson1998).

The most recent Canadian prevalence study concluded that 8.2 per cent of older adults without cognitive impairment were mistreated whereas international rates varied from 0.8 per cent to 36.2 per cent (McDonald, Reference McDonald2015). However, in the handful of studies conducted specifically with older adults with dementia, cared for at home by their family caregiver, OAM prevalence rates increase dramatically to 34.9 per cent (Sasaki et al., Reference Sasaki, Arai, Kumamoto, Abe, Arai and Mizuno2007), 47.3 per cent (Wiglesworth et al., Reference Wiglesworth, Mosqueda, Mulnard, Liao, Gibbs and Fitzgerald2010), 52 per cent (Cooney, Howard, & Lawlor, Reference Cooney, Howard and Lawlor2006), and 62.3 per cent (Yan & Kwok, Reference Yan and Kwok2011). The Alzheimer Society of Canada (2010a) offers a comprehensive review of studies that have assisted in clarifying the risk factors that contribute to this alarming prevalence when dementia and mistreatment coexist. Furthermore, the projected rise in dementia prevalence in Canada (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2010b), aging demographics, and the rise of police-reported family violence against older adults between 2009 and 2017 (Statistics Canada, 2018), demand focused attention on mistreatment of older adults with dementia by their family caregivers.

We can gain knowledge of what occurs behind closed doors by asking those with access: the health care and social service practitioners who visit the home. These data are limited in the current literature, which tends to have focused on prevalence, characteristics of the mistreated older adult and mistreating caregiver, risk factors, and indicators of OAM. Nevertheless, what is recognized is that the experience is complex, that fear and powerlessness may exist, that the burden of responsibility can be overwhelming, and that case outcomes are frequently unfavourable (Beaulieu & Leclerc, Reference Beaulieu and Leclerc2006; Bergeron, Reference Bergeron1999; Omote et al., Reference Omote, Saeki and Sakai2007).

Little attention has been given to the influences of home health, social services, geography, and socio-legal contexts within which this experience occurs. In Canada, as one in six (17%) older adults receiving home care has dementia with high impairment, experiencing moderate to severe difficulty with basic cognitive and self-care functions (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2010), both the informal care provided by family and the formal care provided by the structures of home health and social services greatly influence case outcomes. Next, given rural and northern service inequities and challenges (Health Quality Ontario, 2017), we do not know how rural and northern practitioners experience these cases and what influence geography has on cases.

Finally, in the province of Ontario, Canada, protective legislation currently only exists for victims of intimate partner violence, at-risk adults with developmental disabilities (since birth), older adults in long-term and residential care institutions, and children (Government of Ontario, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c, 2018d, 2019). Limiting legislation to these contexts ignores the fact that many older adults living in their homes are at risk and might need protection from mistreatment.

Methods

This study consisted of two phases: a phase of understanding in which interviews, reflective journals, and inquiry focus groups sought to understand the experience of encountering cases of mistreatment of an older adult with dementia within the home and the contextual influences on this experience, and a phase of empowerment in which action focus groups aimed to awaken a critical consciousness of practitioners’ reality. In this article, data from both phases are combined and presented.

Theoretical Underpinnings

Critical social theory (CST) (Habermas, Reference Habermas and Shapiro1971) provided the theoretical lens for this study. Based on historical realism, CST proposes that current reality is shaped by past social, political, cultural, and economic values (Fontana, Reference Fontana2004). It is concerned with issues of power and control, freedom and oppression, and dominant ideologies and social structures (Harden, Reference Harden1996). It is precisely in the belief that societal circumstances are historically created and therefore alterable, that the goals of CST are grounded: to discover this reality, to challenge it, and to move from “what is” to “what could be” (Mohammed, Reference Mohammed2006, p. 68).

Habermas’s (Reference Habermas and McCarthy1976) concept of moral consciousness also underpinned this study. Defined as the “interactive competence for consciously dealing with morally relevant conflict” (p. xxi), methods were designed to understand participant beliefs, values, and motives related to the complex and sensitive cases of OAM and dementia.

This theoretical framework was also guided by Habermas’s (Reference Habermas and McCarthey1984) theory of communicative action. When understanding is reached by meaningful interaction in an environment free of oppression, communicative reason is reached (Spratt & Houston, Reference Spratt and Houston1999) and collaborative actions are facilitated (Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Treacy, Scott, Butler, Drennan and Irving2005).

The work of Freire (Reference Freire1972) on critical consciousness, the acquisition of critical knowledge about one’s reality, and emancipation, the freedom from the influence of dominant structures and ideologies (Mooney & Nolan, Reference Mooney and Nolan2006), are both philosophically and methodologically congruent with CST notions of ideology critique and empowerment (Fontana, Reference Fontana2004). Critical consciousness, in turn, is required for emancipation, the understanding of one’s experience and gaining the power to control outcomes. All of these concepts are congruent with the concept of professional agency (Frie, Reference Frie2011). Freire (Reference Freire1972) also believed that humans could only actualize themselves collectively. Therefore, the study, designed in two phases, facilitated individual reflection, group dialogue, and collective empowerment.

Phase I: Understanding

To encourage reflection on their experiences in the current contexts, the first author conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with practitioners who visited mistreated older adults in their homes. We asked participants to share a past case of OAM and dementia and to speak freely of their thoughts, feelings, and actions during their involvement with the case. The researcher followed up with questions that would encourage participants to explain the factors that influenced this experience as well as their thoughts on perceived meaningful interventions and ability to control outcomes in order to explore notions of professional agency.

Then, as interviews might only reveal “public accounts”, a reflective journal was added to encourage sharing of “private accounts” including true feelings and beliefs (Bowling, Reference Bowling2009, p. 409). Journal questions were individualized to encourage reflection on practitioners’ unique experience of meaningful intervention, control, and power in these cases.

Third, inquiry focus groups were conducted to reach an inter-subjective understanding, defined as a socio-historical construct and collective reality (Comstock, Reference Comstock, Bredo and Feinberg1982). As dialogue and empowerment are inherent to CST, the focus-group method created a synergy, producing data facilitated by group dynamics (Choudhry et al., Reference Choudhry, Jandu, Mahal, Singh, Sohi-Pabla and Mutta2002). Held in the urban hub of each region, teleconferencing permitted rural participants to join. A hypothetical vignette encouraged sharing of beliefs, understandings, and attitudes related to sensitive matter (Donovan & Sanders, Reference Donovan, Sanders, Bowling and Ebrahim2005). Dialectic reasoning was incorporated in the discussion guide to examine social contradictions and unquestioned rules, habits, and traditions resulting from dominant ideologies and social structures (Duffy & Scott, Reference Duffy and Scott1998). Together, interprofessional practitioners explored existing constraints on their collaboration, communication, and action. Facilitation approaches were used to create communicative spaces where a collaborative reinterpretation of each other’s experiences could occur (Bevan, Reference Bevan2013).

A preliminary descriptive analysis of the data gathered in these first three methods resulted in the production of an interim report. Dissemination of this report prior to the empowerment phase enhanced thematic analysis, ensured credibility of the initial analysis from participant validation, and facilitated communicative action from shared meanings and interpretations amongst participants as they recognized their own experiences in those of others (Habermas, Reference Habermas and McCarthy1976).

Phase II: Empowerment

The second phase of the study, the empowerment phase, aimed to bring about new understandings and change (Comstock, Reference Comstock, Bredo and Feinberg1982). All participants from the interviews or inquiry focus groups were invited to join action focus groups in their region. This method brought together practitioners who, ideally, would collaborate to manage cases of OAM. The goals were to achieve more complex and collaborative understanding (Choudhry et al., Reference Choudhry, Jandu, Mahal, Singh, Sohi-Pabla and Mutta2002) leading to emancipatory knowledge as participants’ critical consciousness of their shared experiences and collective potential increased (Freire, Reference Freire1972). These focus groups concluded with the proposition of action projects to address barriers identified in practice and policy. These projects are reported elsewhere (Lindenbach, Reference Lindenbach2019).

Ethical approval was obtained from the Laurentian University Research Ethics Board and the ethics committees of all participating organizations. The names of these organizations are not disclosed, both to protect participant confidentiality, as those in small rural regions might be the sole representative of an organization, and to address the concerns of some organizations that policies regarding OAM would be revealed and critiqued.

Sampling

Purposive sampling sought practitioners including health and social care providers, community supports, and police officers who had experienced a past case of OAM in the home by a caregiver, and dementia. Participants from five Northeastern Ontario geographical regions were invited. Rurality was defined using the rural small-town definition: “towns or municipalities outside the commuting zone of larger urban centres (with 10,000 or more population)” (du Plessis, Beshiri, Bollman, & Clemenson, Reference du Plessis, Beshiri, Bollman and Clemenson2001). Using data from the 2011 Canadian Census, regions were classified as either rural or urban. Next, although all areas of Northeastern Ontario can be considered “northern” (Health Quality Ontario, 2017), regions were only considered “northern” if winter closures of principal highways prevented access to these communities. Practitioners stressed the importance of this factor in their ability to care for the older adults/caregivers in their care.

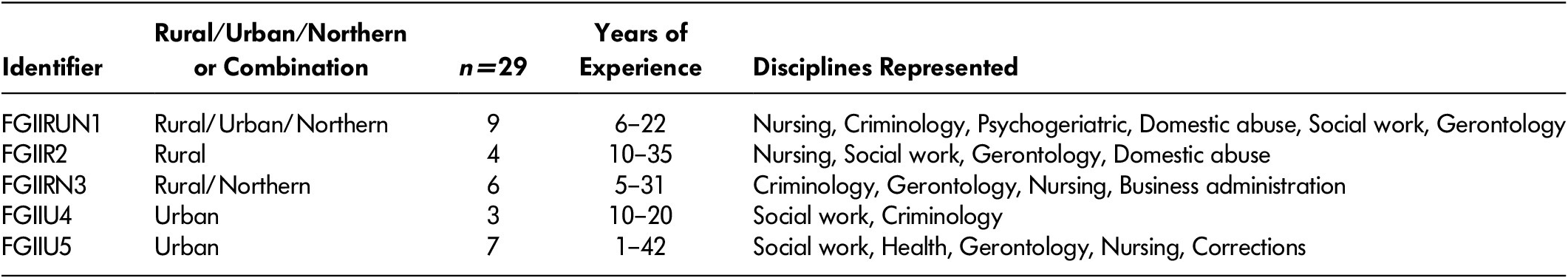

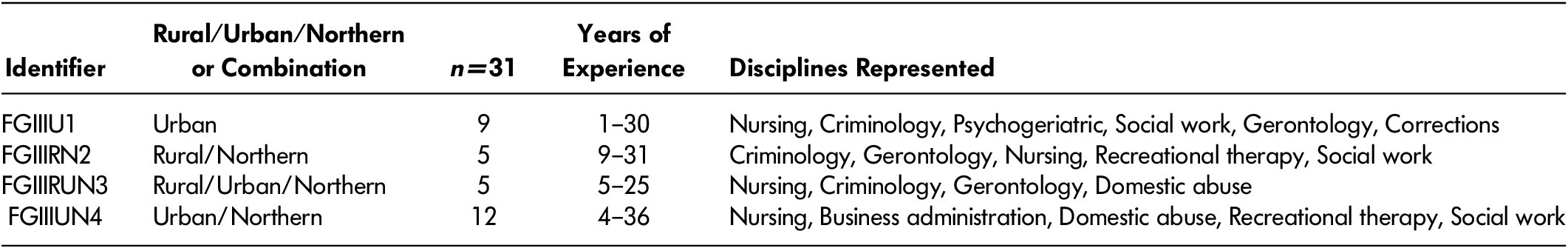

Table 1 describes the interview (n = 28) and journal (n = 19 of the 28) participants. Twenty-nine participants (six of whom had also participated in the interviews) then joined inquiry focus groups, described in Table 2. In the empowerment phase, 31 participants (who had either participated in the interview or inquiry focus groups, or both) joined action focus groups, as described in Table 3. Participants came from various backgrounds and had worked primarily with older adults for between 1 and 42 years. Overall, 51 practitioners participated and 23 Ontario organizations were included.

Table 1: Interview participants

Table 2: Inquiry focus groups

Table 3: Action focus groups

Theoretical Thematic Analysis

The primary researcher (first author) conducted a theoretical thematic analysis on all of the data collected. An iterative process was used throughout data collection to ensure that the final themes represented collective meanings shared by all participants (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Following data immersion, and guided by the research sub-questions, the theoretical framework, and the researcher’s analytic preconceptions, the primary researcher formed initial coding frameworks and began placing data extracts into these coding frameworks using NVivo 11. Revisions of these frameworks continued throughout data analysis of interviews, reflective journals, and inquiry and action focus groups until three final coding frameworks emerged revealing three key themes in the overall study: the experience of professional agency, the contextual influences on this experience, and the need for empowerment. This article describes the analysis of the third key theme: the need for empowerment. An interpretive analysis was then conducted resulting in the identification of candidate sub-themes, which were then repeatedly refined as data extracts were further analyzed, resulting in thick and rich themes.

Results

Findings pertaining to this key theme revealed three sub-themes: assumptions of power and support, collective experiences, and imperative legislation and infrastructure. Having historically struggled with these cases and contexts, participants began by emphasizing an urgent need for empowerment within the current context. Then, recognizing that participants in other Northeastern Ontario regions shared their experiences, they demonstrated an appreciation of each other’s barriers. Finally, participants from all regions unequivocally were adamant that empowerment could not occur without the development of legislation and infrastructure. To support this thematic analysis, verbatim excerpts are offered followed by an acronym identifying the discipline and geographical region of each participant. Readers may refer to the tables provided to reference the excerpts to these identifiers.

Assumptions of Power and Support

Participants described a perpetual cycle of non-resolution, within which they or families unsuccessfully reached out to all available services listed as possible OAM resources: “It discouraged me. You call the elder abuse hot line and they tell you to call the police. And you call the police and they tell you to call the hot line” (SWRN16). Ultimately, case responsibility returned to rest with the individual practitioners. Powerlessness led to hopelessness: “They would call me and I knew I didn’t have an answer” (FGIIIRN2). This admission was reiterated in other focus groups: “Sometimes my blinders go up to be honest because I know that nothing much is going to get done” (FGIIIRUN3). This hopelessness was seen as an erosion resulting from longstanding unsuccessful efforts: “…just being disenfranchised” (FGIIIRN2); “disappointing …people don’t find the responses that they feel are appropriate for what they’re seeing” (FGIIIUN4).

Participants described a lack of positional power accompanied by a sense of responsibility: “We all have innovative ideas but no one is in a position to implement them. As I am putting these feelings on paper, I know that someone out there is being neglected and abused and we are not doing enough to help them” (FGIIIRN2).

As participants from different backgrounds shared their obstacles, previously held assumptions of positional power were replaced with a new understanding that all were powerless within the existing contexts: “She [police officer] had huge concerns but there wasn’t much they could do…she [older adult with dementia] was agreeable for them [mistreating sons] to be there” (NurRN15). Participants who had maintained hope for provincial legislation permitting them to resolve cases described the public’s expectations of protection:

• We are a fluff…[the expectation is] that we’re going to come in as a group and go walk into that and take care of it?

• A lot of people think that too when they call.

• That’s what we were hoping to accomplish.

• 25 years later, there’s nothing in place. (FGIIIRN2)

Participants were adamant that provincial efforts needed to change from their current focus on education to one of intervention: “I’m sick of being told… I can tell you verbatim everything about abuse. I could tell you the sexual abuse, emotional, all that, but ask me what to do about it and I go blank. I don’t know what the hell you do about it, I just know it exists” (FGIIIU1).

There was no provincial supportive legislative to address complex cases of dementia: “This is what we always say, it’s great that it’s on everybody’s radar. But when your hands are tied, there’s not a whole lot you can do about it… with people with dementia, [it’s] not so easy” (FGIIIUN4).

Some participants had recently attended a provincial program, again focused on education about OAM. Given their vast knowledge and experiences with challenging OAM cases, many were frustrated by this focus, which they viewed as repetitive and stagnant: “Did we not feel that when we were at that? [title of provincial training] It just hit us like a ton of bricks that we’ve gotten nowhere and we’re still nowhere… [agreements from group] …Sad eh? That was awful. I walked away from that going this was the worst experience I’ve had” (FGIIIRN2).

Not only did practitioners want to be empowered and supported, they also voiced a responsibility to advocate for caregiver support in cases in which lack of respite contributed to OAM: “The caregiver becomes at risk of potentially harming… we try to avoid hospital admissions but sometimes, the risk is too high because of the limitations of [in-home] services” (FGIIIU1). Again, participants witnessed the impending crisis: “I had one son say to me: I’m on the brink… I’m going to, something bad is going to happen” (NurRUN20). Participants felt that important research and policy documents promising increased caregiver support, which should inform home care decisions, seemed to be ignored: “there’s a sense of apathy in spite of all the reports like the Rising Tide Report. We know that tsunami’s already here, it’s not coming, it’s here. The system just doesn’t recognize it” (FGIIIUN4).

Participants pressed for the system to recognize the caregiver: “We’re saying to 84-year-old mom … that’s your husband with Alzheimer’s, good luck, we’ll see you to bathe him twice a week for half an hour! Really, they need more support!” (FGIIIRN2). Although the current system provided some support and educational programs, in-home respite hours and day programs were insufficient; caregivers needed “so much more than what we can provide” (FGIIIUN4).

This participant explains the precarious situation created for caregivers coming to her support group, caused by insufficient in-home respite: “When people come to our group, do you know the stress that they go through? …they’re checking the clock. A lady, when she got back home to her husband, the worker had left, …she was 10 minutes late. He had diarrhea all over … so, is she excited about coming next week without worrying about him?” (SWRN16)

Collective Experiences

The study design, in particular the dissemination of the interim report describing the experiences of all participants and the focus-group methods, facilitated a process of sharing in which participants realized that they were not alone. This focus-group participant reflects on her realizations as she read the interim report: “I thought, all these people are saying what I’ve been through…all these years…it’s never really been down on paper in such a reality… all these things that you’ve already been through and felt helpless” (FGIIIRN2). Although this shared experience was reassuring, reading the report was also distressing: “There’s nothing we can do, we might as well… just what are we going to do? Just turn our eyes away? It was awful. I felt that way, reading everybody’s scenarios” (FGIIIRN2).

Progressively, as comfort increased within the focus group, participants felt at ease sharing challenges related to their professional roles that other practitioners in the focus groups may not have understood. A police participant spoke of others’ possible perceptions of his lack of action: “If we couldn’t get in the house to verify, it’s sometimes interpreted as if the police didn’t do anything… there’s very limited legislation when it comes to trespassing into someone’s home without prior judicial authorization, without warrant or otherwise” (FGIIRUN1).

This obstacle was also evidenced after a case study was presented to the focus group. In it, a neighbor had called police after hearing screaming from the home: “Police action is very evidence-based so the neighbor hearing a scream the night before, it’s not evidence to allow us to take further action” (FGIIIRUN3). Different understandings of the concept of evidence highlighted the complexity of working in interprofessional teams where practitioners are socialized in their own language and are guided by different legislation.

Participants discussed a second obstacle to teamwork: long-standing interorganizational and interprofessional conflict. Inquiry focus-group discussions revealed frustrations and the underlying belief that some organizations ignored OAM: “How often do we hear that from the [name of organization] saying, it’s not our mandate” (FGIIU5).

As focus groups progressed, and comfort in sharing increased, participants openly voiced these conflicts revealing lateral conflict as evidenced in this action focus-group exchange:

• -Well that ends my job right there, I can’t do anything… I can’t force you [to accept services for the patient with dementia where mistreatment is suspected].

• (other) I know but it wouldn’t trigger any alarms like for you?

• (other) But you would take it one step further?

• (other) Yes, but I can’t, you can’t force your way in anybody’s house.

• (other) Yes, I guess I’m just hoping that you know as a professional…. That you would say, something’s wrong here and ….” (FGIIIU1).

With ongoing discussion, participants shared their own organizational limitations, including specific eligibility criteria, strict service allotments, and legislation to be respected within their roles. As new understandings occurred, participants developed a new appreciation of others’ challenges and inability to intervene in these cases. This social worker verbalized empathy as she reinterpreted the inaction by a colleague not as a choice to disregard the OAM but rather as fear: “She said, well I thought there may be [OAM] but I wasn’t sure … she was afraid of what might potentially come of it all, and didn’t have the comfort level to deal with it. So, when I stepped in, she was relieved” (SWRUN17).

Despite this recognition, factors such as workload impeded teamwork: “I feel bad saying that but, especially up here, the caseloads, the work that we have; I don’t find it’s practical…” (FGIIIRUN3). The lack of tangible outcomes was also a barrier: “It’s discouraging for us, as a group to sit at round tables, always come up with the same issues and never a resolution” (FGIIIU1). Again, there was the notion that practitioners were powerless to effect change until a crisis surfaced: “You can guarantee that everyone here …We tried this, we did this, now what? And then we wait [for the crisis]” (FGIIIRUN3).

The success of teamwork sometimes entailed breaking/bending the rules: “People can be very creative… in terms of how to get people services that they don’t really qualify for. There are people willing to go above and beyond that rhetoric” (FGIIIU1). However, bending the rules was risky: “I thought, I’ll likely get called on that but this is patient focused and is going to work…and it did” (NurU27). Although participants were uncomfortable with rule bending/breaking, it was justified “when you’re worried that somebody’s safety is at risk” (FGIIIU1); it’s “being there for that senior” (FGIIIU1).

Next, participants wanted to abide by privacy legislation when working together, a root cause of past failed attempts to teamwork: “We did have a case review team, but we were breaking rules…everybody knew who you were talking about” (FGIIIRUN3). Unable to disclose information with those outside the health and social services team, practitioners wanted to be able to share concerns legally: “…significant weight loss, bruising, multiple falls…you start questioning, like with children…constant emerg visits… Why are they always in a delirium? What’s going on? An officer’s not going to be able to identify that” (FGIIIUN4).

Some suggested a non-specific disclosure to police but others expressed caution:

• I may not be able to say to him [police], it showed on Meditech that this person has broken their arm x times …I could say, ok there’s really something going on, I can’t specify, but …

• (other) You’d have to be very careful. (FGIIIRUN3)

A final barrier to collaboration was the lack of a shared interprofessional language: “We are credible but yet…. we need to be comfortable with what terms they [police, lawyers] use…that give us credibility” (FGIIIU1); “Knowing the legal jargon…so I’m not completely overwhelmed and fearful…What do I need to empower myself?” (FGIIIUN4).

Interestingly, two factors facilitating collaboration were identified. In northern urban hubs, where practitioners also serviced the smaller surrounding rural communities, participants described advantages to teamwork. They described a tight network in which collegial relationships prevailed: “Knowing who to contact and already having that relationship built with the service providers. I was able to call in key people that I knew could help me…and they knew to call me” (GerRUN5). The ability to trust other members of the team was key: “There is also the element of trust …you know that they are good…you trust their judgement …they are doing is in the best interests” (SWRUN17). This positive team environment contributed to a safety net: “In Northern Ontario, people, once they’re in the system, there’s less chance they will fall through the cracks… we catch them to do a follow up or make sure someone else is doing a follow up. It’s because there is just more relationship between services and fewer people working” (RtRUN7).

Second, despite the long-standing challenges in this field, participants remained committed: “I’ve been in this position for 31 years, and I’ve seen people come and go … all have that sense of commitment and investment … never throwing up our hands” (FGIIIRUN3). The shared experiences they had within their communities, and within the five regions of the study, inspired a collective strength. Participants were hopeful “to obtain a voice in effecting change to improve quality of life for persons identified in this study” (FGIIIUN4).

Imperative Legislation and Infrastructure

Despite attempts to work together and good will, the lack of specific OAM legislation was an overwhelming obstacle to entering a home and intervening. Comparisons were made with legislation for the protection of children, as participants reiterated that mistreatment was unacceptable, regardless of age: “A parent can’t abuse their child, a child should not be able to abuse their parents. I don’t think it’s that complicated” (FGIIU5). This police participant explained how specific legislation for children supports interprofessional practice and entry into the home: “With CAS [Children’s Aid Society], there’s a legislative authority, that’s the difference…we rely on their [CAS social workers] information to establish our grounds to believe there’s a child in need of protection …that authority kicks in under the Child Family Services Act” (FGIIRUN1).

Overwhelmingly, participants felt that they, like CAS workers, should also be “relied upon”. Discussion continued regarding suspicion versus evidence: “Unlike children, where suspicion is sufficient to warrant police investigation, here, we need proof that that fracture is due to OAM before involving police” (FGIIIRUN3). Participants longed for similar supportive infrastructure: “They have legal counsel, they are guided, they have supervisors, they have guidelines, we have none of that…this system isn’t built that way. In fact, it’s not built at all” (FGIIRUN1).

Ultimately, participants wanted the ability to protect mistreated older adults. Aware that this entailed a possible connotation of ageism, caution prevailed: “We need to systemically move a little bit more to that end…if in my professional opinion, this person has cognitive impairment and is not able to make informed decisions… I will ethically do my due diligence to protect this person” (FGIIU4).

Borrowing legislation from other at-risk groups was a strategy used when applicable. This police officer describes applying domestic violence legislation with mistreated older women, where an intimate partner relationship existed: “If that person’s intimate partner is the culprit, we can pursue that person because it falls under the domestic violence say criteria. [But] if that person’s son, daughter or caregiver [is the perpetrator], where there’s no intimate relationship or never has been, then the domestic violence process does not apply” (FGIIRUN1).

Nevertheless, borrowing interventions from domestic abuse was problematic. For example, placing someone with dementia in a women’s shelter, a frequently cited intervention in provincial handouts, was deemed inappropriate: “We cannot force her to come to the shelter…and when you take somebody with dementia out of their routine and area … there’s so many risks” (FGIIIRUN3). These shelters would fail to meet the needs of these older adults: “I’m not going to put a dementia patient in the shelter. [They need] people who are trained in dementia, twenty-four-hour care” (GerRUN5).

When domestic legislation was not applicable, and the Criminal Code of Canada was the only legislation supporting legal intervention, evidence of crime and capacity had to be considered: “Information from the victim…it all boils down to that…disclosing what happened and reporting it for criminal investigation… if the victim, being of sound mind, does not want it pursued, ultimately our hands are tied yet again” (FGIIU4).

The need for OAM protective legislation was the strongest conviction linking participants from all regions. They shared their frustrations freely, although difficult to hear: “If we were kicking a dog or a child, [moans from group], exactly, it’s prescribed. But you kick an elderly person, and she says, no I’m okay with being kicked, nothing … It’s just so frustrating to work in this field!” (FGIIU5).

Participants could not understand why older adults could not be addressed in their own legislation when dementia created risk: “There is no adult protective services act, unless it’s for the developmentally handicapped. It’s just a sort of a sense of well, why isn’t there?” (FGIIU4). Overwhelmingly, it was felt that this province failed mistreated older adults with dementia. Some spoke of the resistance to recognize dementia as a risk: “They changed the laws around domestic abuse so that you no longer had to have the consent of the victim to press charges …You don’t ask for consent in a child abuse situation. But sometimes, we almost have to treat adults as if they are eight years old, because we have to be where that person is [in their dementia]” (FGIIIUN4).

Participants were cautious in this discussion, verbalizing that rights to autonomy for capable older adults had to be maintained. Others verbalized frustration with a system that frowned upon the protection of the older adult at risk where outcomes were unfavorable. They believed the current context failed to ensure their right to protection: “It’s a tough balancing act but our laws currently sway in the wrong direction. We need to strive towards a society where we recognize [that] people with dementia, that have limited or no capacity, have the right to protective services” (FGIIIU1).

Although initially cautious with such statements, they eventually expressed this with conviction: “We’re told: my dad has rights! But he has a right to be protected; he doesn’t have a right to be abused” (FGIIIRN2).

Participants clearly perceived a responsibility to protect those at risk: “I have to act; I feel it’s our duty to each other and [our] human responsibility to not turn away” (FGIIIRN2). However, they did not believe that society acknowledged this responsibility: “We’re a backwards society, let’s face it. You could abuse your kids but you couldn’t abuse your dog before. There were laws created to protect animals before children. That legislation existed in the late 1800s however the Child Protection Act didn’t come to be until the 1980s” (FGIIU4).

Legislation and infrastructure were believed to be essential to unequivocally recognizing the protection of older adults at risk as being someone’s responsibility. Until OAM had its own specific legislation and infrastructure, it would remain unrecognized by society and unaddressed by government: “It’s [management of OAM cases] not part of our mandate, so it’s being picked up in fragments… There’s no data” (FGIIIUN4).

Discussion

The design of this study, supported by the theoretical foundation of CST, critical consciousness, and professional agency, led to understanding the need for empowerment in contexts in which individual and interprofessional efforts were challenged by the absence of legislative and infrastructure supports. Practitioners came to understand, by learning of others’ challenges, that they were not alone. Together, they realized that although all were committed, insufficient contextual supports rendered case resolution an unrealistic outcome. The discussion will now address the themes of current contradictions, the realization of a collective experience, and the urgent need for supports as proposed by participants for those older adults with dementia who cannot choose to end the mistreatment.

Contradictions

The first theme, assumptions of power and support, reveals a societal contradiction: the expectation that practitioners have the power to resolve cases of OAM as opposed to the inability that participants described to protect mistreated older adults with dementia in their care, in a perpetual cycle that they were powerless to break. Although guidelines are offered in provincial handouts, it is in their application that flagrant flaws were revealed by participants. One commonly recommended intervention in the grey literature was reporting concerns to police, some even adding that an anonymous report was acceptable (Community Legal Education Ontario, 2018; Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility, 2016). However, this strategy would not be helpful in the home context because of the required threshold of reasonable grounds to warrant access (Skolnik, Reference Skolnik2016). Furthermore, as the only means of laying charges was the Criminal Code of Canada (Government of Canada, 2018), evidence that a crime was committed was required. Beaulieu, Côté, & Diaz (Reference Beaulieu, Côté and Diaz2017), in an action research project with police in Montreal, Quebec, a legal context also without adult protective legislation, described the scarcity of research on police roles, needs, and contributions to interprofessional OAM efforts. Without this evidence, there is no understanding of their practice challenges. A second recommended source of assistance, contacting the provincial seniors safety line, frequently led to a problematic provincial cycle of perpetual ineffective referrals, as no one entity had the power to stop the OAM. Participants in this study were therefore limited to interventions to mitigate risk, a finding previously reported by Lithwick et al. (Reference Lithwick, Beaulieu, Gravel and Straka1999) with their practitioners in a similar socio-legal context in the province of Quebec, Canada.

Since 2002, the provincial system’s patterned response has been to repeatedly provide education on what OAM is, as well as its forms, indicators, and risk factors. This drive surely stems from research conclusions that practitioners require more knowledge on OAM and education to shift their attitudes (Harbison, Reference Harbison1999; Stones & Bédard, Reference Stones and Bédard2002; Vandsburger, Curtis, & Imbody, Reference Vandsburger, Curtis and Imbody2012). However, in a study conducted in the United States (where adult protective legislation exists) looking at variables predictive of appropriate clinical decision making, years of experience and applied knowledge, rather than education, significantly influenced OAM recognition and intervention (Meeks-Sjostrom, Reference Meeks-Sjostrom2013). When considering the high level of knowledge held by these study participants, the assumption of lack of knowledge is misguided, and has the effect of devaluing their struggles with these cases. Nonetheless, those without power to change the legislation and create the corresponding infrastructure cannot be faulted for repeatedly delivering this education. The public certainly requires education about OAM, and new practitioners require this sensitization, as it is seldom addressed in post-secondary education. However, participants in this study, fully invested in OAM efforts, pleaded for the province of Ontario to finally push beyond the envelope of education towards that of intervention, legislation, and infrastructure. As per the broad social view of CST, which insists that for a phenomenon to change, the context in which it occurs must first change (Fontana, Reference Fontana2004), participants urged for the socio-legal context of OAM in the home to be transformed. Without contextual change, they knew, from their historical efforts, that OAM would persist.

Practitioners also pleaded for reform to the home care system to properly support caregivers who may mistreat the older adult with dementia in their care. Current respite provisions were deemed inadequate in a system that was primarily focused on patient needs. Although support groups were available and participation resulted in positive outcomes, insufficient home care respite resulted in increased stressors for caregivers leaving the older adult. It is hoped that the newly adopted federal dementia strategy (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019) can influence the home care system to provide proper supports for caregivers with the goal of preventing OAM. There are two mentions of mistreatment (abuse) in the document addressing gender-based violence and improvements in the federal criminal justice system. The document also refers to strategies specific to the province of Ontario: “the expansion and enhancement of community dementia programs and in-home respite” (p. 70) and the “Enhancing Care program, which provides therapeutic skills training to family or other care partners who provide care to individuals living with dementia” (p. 70). Participants in the current study were skeptical that this or any new government policy document would result in concrete assistance for caregivers, and voiced disapproval that the new program would download further responsibility of care onto caregivers.

Realization of a Collective Experience

The guiding concepts of professional agency, empowerment, and emancipation are all communal activities that require collective action by communities or groups experiencing the same limits to their actions (Halman, Baker, & Ng, 2017). The study resulted in understanding that individual practitioners shared a collective experience of powerlessness.

Participants reached a critical understanding of lateral conflict as a characteristic of oppression (Freire, Reference Freire1972). They described feeling oppressed in the current socio-legal context of OAM in the home. As the study progressed, they realized that the lack of contextual supports, rather than each other, was the source of lateral conflict and of their lack of professional agency. Literature on conflicts among practitioners in OAM cases could not be located, although this has been studied with child abuse (Newman & Dannenfelser, Reference Newman and Dannenfelser2005) and with nurses who experienced oppression (Roberts, Demarco, & Griffin, Reference Roberts, Demarco and Griffin2009).

By discussing challenges to teamwork, participants shared how bending/breaking the rules regarding service limits, eligibility criteria, and confidentiality occurred. Such rule bending has been described with other health care practitioners as a coping mechanism when experiencing moral distress in a situation that they cannot control (Corley, Reference Corley2002; Kontos, Miller, Mitchell, & Cott, Reference Kontos, Miller, Mitchell and Cott2010). Although possibly bringing about positive outcomes in an OAM case, the professional risks that some practitioners were willing to take to protect the mistreated older adult also resulted in corroding future collaboration when rule bending/breaking was expected but ceased to occur.

Furthermore, privacy legislation, although facilitating the sharing of information in cases of imminent and serious harm (Solomon, Reference Solomon2019; Wahl, Reference Wahl2013), was an impediment to addressing cases before they reached that severity. Although Ontario practitioners have been reproached for not understanding privacy legislation thus legitimizing inaction (Wahl, Reference Wahl2013), information disclosure and confidentiality have been reported as critical limitations by practitioners in similar legal contexts (Beaulieu et al., Reference Beaulieu, Côté and Diaz2017). The ethical implications of being prevented from disclosing concerns of mistreatment, prior to a crisis, demand to be addressed.

Differences in linguistic conventions between practitioners and those with decision-making power outside of the home (i.e., supervisors, police, and lawyers) contributed to practitioners’ feelings that they lacked credibility, and undermined their confidence. This is in keeping with Habermas’s (Reference Habermas and McCarthey1984) notion of communicative reason, whereby front-line practitioners did not feel able to engage with legal institutions on an equal footing within a dominant context of legal complexity. Participants felt that shared linguistic conventions by all practitioners, police enforcement, and legal representatives, would lead to desirable outcomes of credibility, lateral conflict resolution, reliability of assessment, shared understanding, and collaboration.

Despite these barriers, a contributor to successful collaboration was discovered with those practitioners and teams that were a combination of rural, urban, and northern who described tighter knit teams, where practitioners spoke of trust, a necessity to rely on each other because of scarce resources, and knowing whom they could call upon for assistance, as well as serving as a safety net to catch older adults when OAM reached its inevitable crisis. These findings echo those of others who have described positive working relationships in Northern Ontario as a “northern advantage” (Health Quality Ontario, 2017). However, in strictly rural regions, resources were insufficient to create this local team, and practitioners struggled with this sole burden.

Urgent Need for Supports

As OAM does not rest on its own legislation and infrastructure in this province, practitioners are expected to have knowledge of, and be correct in the application of, numerous pieces of applicable legislation, complex legal knowledge that falls outside their scope of practice. Participants pressed for protective legislation for older adults rendered at risk by dementia living in their homes, as it currently exists for older adults in Ontario long-term care and residential care (Government of Ontario, 2018b, 2018c; Hall, Reference Hall2009). Participants argued that providing intervention in cases of OAM is justified, similarly to domestic violence and child protection legislation. This position has been adopted in the United States, where adult protective legislation efforts date from decades ago (Bergeron, Reference Bergeron1999). More recently, in the United Kingdom, legal reform is recognizing that duty to address mistreatment is “owed” to older adults (Spencer-Lane, Reference Spencer-Lane2010, p. 45), placing it “on par with child protection” (Williams, Reference Williams2017, p. 180).

Participants viewed an older adult’s right to safety as a basic human right currently not being ensured for at-risk older adults remaining in their homes. This is in keeping with the position of the Ontario Human Rights Commission (2001) and with the Canadian Association for the Fifty-Plus that “elder abuse and neglect should be identified as abuses of human rights” (p. 67) and recommendation that “mechanisms currently in place to address other forms of familial abuse should be extended to apply to elder abuse” (p. 72). However, in some Canadian grey and scientific literature, advocating for older adult protective legislation has historically been considered ageist (Advocacy Centre for the Elderly, 2008; Harbison, Reference Harbison1999).

Working within this dominant narrative, practitioners who sought older adult protective legislation described oppression. Their efforts were stifled. They viewed the lack of protection offered to older adults, compared with that offered to other groups, as systemic ageism that perpetuated a lack of societal value for older adults. Given the legitimacy of concerns regarding past legislative abuses of older adults’ autonomy (Harbison, Reference Harbison1999), this tension between ageism and protectionism reveals important practice/research/policy gaps that must be addressed.

In provincial guidelines, an ethical delineation must be drawn between principles of care for two starkly different populations that are seldom considered apart: upholding the autonomy of those older adults who are capable of choosing to remain in a situation of mistreatment, and providing protection for older adults with cognitive impairment who cannot choose to accept the mistreatment. This difference has been addressed in the United States, as Anetzberger (Reference Anetzberger2000) explains that although an empowerment approach is appropriate with independent victims of OAM, a protective approach is needed when cognitive capacity is challenged. Others have proposed that the predominant victim empowerment model in many Canadian provinces is missing those older adults that are most at risk of OAM (MacKay-Barr & Csiernik, Reference MacKay-Barr and Csiernik2012).

Two aspects were especially problematic for practitioners in these cases: having their concerns about vulnerability, impaired capacity, and risk validated within a context in which they were powerless; and being unable to stop the mistreatment until cases reached a crisis (Lindenbach et al., Reference Lindenbach, Morgan, Larocque and Jacklin2020; Lindenbach et al., Reference Lindenbach2019). Practitioners explained that currently, in Ontario homes, the mistreatment of older adults with dementia remains hidden from public scrutiny within a home care system where fiscal restraint impacts care, society fails to recognize the risks of OAM and dementia, and a legal system cannot support intervention. To bring OAM out of these shadows, it must be legally recognized as unacceptable. Again, in the United Kingdom, Cooper and Bruin (Reference Cooper and Bruin2017) have cited that placing adult safeguarding on a statutory footing resulted in the doubling of referrals to 100,000 in the first 6 months following the enactment of legislation. It is essential that the province of Ontario recognize the need to introduce adult protective legislation and infrastructure to support practitioners in their efforts.

Currently, without legislation or infrastructure, involvement in OAM efforts is self-driven, based on personal beliefs and values of dignity and protection. This represents Habermas’s (Reference Habermas and McCarthy1976) concept of moral consciousness as participants questioned policies, advocated for older adults, and persisted despite the lack of supports (Sumner, Reference Sumner2010). However, they felt alone in this battle. The lack of organizational mandate of OAM case responsibility in Ontario and resulting self-driven efforts by practitioners must be addressed.

Limitations and Conclusion

These study findings contribute to our knowledge in the field of OAM. These include: a perpetual cycle of non-resolution and self-driven efforts related to the lack of a legal mandate assigning responsibility and authority to an organization or discipline to address OAM occurring in the home in this province, the problematic assumption of practitioner lack of knowledge, the bending/breaking of rules occurring when unable to resolve the OAM, the unrealistic knowledge demands on practitioners to be competent with numerous pieces of legislation, and practitioners’ perception of lack of adult protective legislation as a form of systemic ageism. These findings merit further investigation and discussion.

This two-phase study was fruitful because of the time shared with participants in face-to-face interviews, inquiry focus groups, and action focus groups, and repeated travel throughout Northeastern Ontario. However, this extensive travel and data collection resulted in insufficient time to accompany groups with their action projects. As per Choudhry et al. (Reference Choudhry, Jandu, Mahal, Singh, Sohi-Pabla and Mutta2002), in addressing empowerment, ongoing support and energy are required to ensure and sustain action for change. The primary researcher will therefore continue to assist with the action projects outside of this study.

Attempts were made to have participation from all geographical areas in the target Northeastern regions, and from all pertinent home care, social services, and police enforcement. However, recruitment was challenging, especially in some rural and northern communities with limited human resources and because of workload challenges in all communities. Despite this limitation, this is the first Ontario study to ask front-line practitioners about their experience with OAM and dementia.

Although focus groups were designed to serve as communicative spaces, some obstacles served as deterrents: workload obligations which resulted in last-minute cancellations and smaller size focus groups; urgent caseload issues which interrupted some participants during the focus-group time; and long-standing lateral conflict with some organizations resulting from the oppressive legal and home care contexts. The latter resulted in argumentation, which in itself, is actually welcomed (Habermas, Reference Habermas and McCarthey1984), as it can lead to uncovering layers of understanding otherwise unavailable. Although transcription of audiotapes was challenged by these passionate discussions, and participants were fatigued by the end of the 3-hour focus group, overwhelmingly, participants’ comments suggest that they were grateful to have had the opportunity to share their experiences and have their voices heard.

At the conclusion of the study, participants saw possibilities beyond their limited situation and felt empowered. According to Lincoln, Lynham, and Guba (Reference Lincoln, Lynham, Guba, Denzin and Lincoln2011), therein lies evidence of the validity of CST research. However, participants remained doubtful, having been devalued in the past in a provincial context where their efforts could not protect the at-risk mistreated older adults whom they cared for in their homes.

In conclusion, in Ontario, multiple efforts are made by dedicated practitioners at the provincial level to address OAM. This study does not negate those efforts; it instead asks us to consider that any action, without changing the contexts in which these actions occur, will result in the same outcomes. Therefore, continuing to provide education in Ontario, without addressing the non-legislative approach to OAM, and not recognizing the risk for older adults with progressive dementia, will maintain the current stagnation in this field. There are important policy-research-practice gaps in OAM and dementia in this province. The experience of front-line practitioners in Ontario has never been compared with what practitioners experience in other Canadian provinces that have adult protective legislation. This type of research is warranted. Organizations are expected to provide policy guidelines for their employees, but they do not have provincial government guidance. Front-line practitioners in this province, who have the distressing privilege of witnessing OAM behind the closed doors of the home, and struggle unsuccessfully to eradicate it in the current provincial contexts, urge us all to consider their realities as an incipient point for policy change. The cases of OAM shared by these practitioner participants have thus far been invisible to policy makers: they have not progressed enough to be captured in police statistics on reported crime, and are not reflected in national prevalence studies from which older adults with cognitive impairment are excluded. These cases of OAM can therefore only be revealed by understanding the experiences of practitioners in the home, and how dedicated they are to the older adults they serve.