“Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being, or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it. It is nevertheless the map that precedes the territory—precession of simulacra—that engenders the territory…”

- Jean BaudrillardFootnote 1Cartography anticipates and creates jurisdiction. By circumscribing the limit of the law of the land, what common law renders as the legem terrae, cartography inaugurates the modern form of jurisdiction through the visual creation of territory. From the Treaty of Tordesillas to the Boundary Commissions in India, from the Berlin Conference to the Irish Boundary line, it was a stroke on a parchment, a textual notation, that ultimately divided land, gradually distinguished territories, and created jurisdictions. Although investigations of the role of cartography in legal claims-making, in the creation of jurisdictions, and in visually appropriating land as territory have burgeoned in the recent past, such examinations are yet to receive sustained attention in legal scholarship. There does, however, exist a slowly growing interest in cartography from a legal perspective, although it remains in the main ignored in the Indian context.Footnote 2 This paper will engage with the early colonial maps of the British East India Company to analyze its representative, as well as creative, functions, delineating how maps represent existing legal relations, entrench hierarchies, and visually transmit projected, and aspired, notions of legal authority and sovereignty. In this way, this paper will contribute, from an Indian context, to the literature on cartography's role in jurisdictional ordering, societal reordering, and legal claims-making of territorial sovereignty.

There exists a significant history to lines inaugurating legal territories, which have played a constitutive role in the longue durée of many legal systems. In the words of Cornelia Vismann, the “primordial scene of the nomos opens with a drawing of a line in the soil. This very act initiates a specific concept of law, which derives order from the notion of space.”Footnote 3 For a long time now, however, the drawing on the soil has followed, if not been subsumed by, a drawing on a paper.Footnote 4 Whether it is an inscription on the surface of the earth, drawn on the soil, for cartography literally means “to write the Earth,”Footnote 5 or whether it is a line across a text, as on a map, both drawings institute order.Footnote 6 As the first constitutive act of drawing and imaging the territory, cartography inscribes the terrestrial limits of a rule, and provides the parchment basis for law's territorial authority. In many historical contexts, it was maps that visually established the law and affixed it with a material basis and tellurian justification. Such a primeval performance can be traced back at least to the bronze age, as witnessed in the networks of petroglyphs inscribed on the Bedolina rock in the Val Camonica valley during the Neolithic revolution. As Christian Jacob has argued, what such a protohistoric instance demonstrates is the use of a primitive method of cartography—delineating ownership, title, and possession—as an “instrument of management,” as a visual means to order “collective life,” providing a public presentation of title to land and ownership, and resolving disputes regarding them.Footnote 7 The Bedolina Map, Jacob asserts, “is the law. In dissolving the particularity of individual points of view and of territorial practices in a mechanism pertaining to an abstract and impersonal gaze, in going beyond the conflicts of local interests and the limits of property and by creating a collective order in which syntax prevails over singular entities, the map is clearly a political instrument.”Footnote 8 This ancient map, this petroglyph situated at a distant height overlooking the valley, necessitating a ritualistic climbing of the hill to view and read the oracular law, provides an early indication, if not a genealogical basis, of the legal operations of a map.Footnote 9

In ordering space, place and legal relations, a map is an ignored facet of legal studies, a precursor to institutional performances, and an artifact that lays down a visual groundwork for social order and lawful conduct. This paper studies the constitutive role of cartography, apropos law, territory, and social order, in a specific historical context, by examining the crucial political role played by the British East India Company's cartographic practices and maps in aspiring and imagining the transplantation and establishment of English sovereignty in the Indian subcontinent. This paper will also show how British maps visually entrenched and supplemented unique forms of social hierarchy and marginalization, and legal categories and stratifications, in Indian cities. By analyzing maps, memoirs, cartouches, dedications, ornaments, plans, prospects, and historical manuscripts appertaining to the eighteenth and early nineteenth century operations of the Company, this paper will demonstrate, firstly, that cartography preceded, visually imagined, and set the stage for the coalescence of British sovereignty and the expansion of its law in the Indian subcontinent; secondly, that cartography provided the visual support for social ordering; and thirdly, that maps do not have a singular function. Maps are capable of not just representing territory, what Shaunnagh Dorsett and Shaun McVeigh have characterized as a legal “technology of representation,” but also of anticipating territory and providing legitimacy ex ante to governance and rule, orienting and ordering a space in order to convene law and authority.Footnote 10 In other words, what the cartographic operations of the Company demonstrate is that law is preceded by a jurisdictional politics of spatial ordering, encompassing a complex network of visual processes, which have been predominantly neglected in Indian legal history. As Matthew Edney has claimed, the British East India Company's “maps came to define the empire itself, to give it territorial integrity and its basic existence. The empire exists because it can be mapped; the meaning of empire is inscribed into each map.”Footnote 11 This paper will exhibit how maps, as relevant jurisdictional texts, preceded legislations in making claims for British sovereignty, how cartographic practices imagined and expanded juridical institutions, how cartographic plans of cities reproduced and visually entrenched social hierarchy, stratification and division, and how cartography performed, to venture in a neologism, a cartojuridism that de-exoticized a foreign and threatening land and enabled a unifying juristic vision to take hold. The notion of cartojuridism signifies the diverse ways in which maps are related to legal functioning: such as distantly making legal claims of sovereignty (as in the contexts of Tordesillas, the Australian hinterlands, or the early colonial charters of the American mainland), anticipating and creating territory (such as the mapping of Siam),Footnote 12 visually aspiring for the inauguration of sovereignty in possessed territories (as in the case of Bengal), or in pictorially representing, entrenching, and reconstituting social hierarchy and order (as in Madras and Calcutta).

Nations, in the sense of imagined communities, can coalesce and enforce territorial rights, through which a supposed collective will can dominate within a bounded space, only on the basis of maps.Footnote 13 It is cartography that defines where one rule ends, and another begins. In the history of the British Empire in India, it was on the basis of maps that a uniquely British India—a British understanding of their India—developed, through which their regulations and law could be uniformly applied upon the visually unified territory.Footnote 14 As Dorsett has adduced, it was the kind of territoriality that developed through post-Enlightenment mapping practices that enabled the uniform imposition of the same institutional and administrative arrangements across swathes of territory, whether contiguous or non-contiguous.Footnote 15 In the Indian context, as will be elaborated below, it was the surveys and early maps that provided the first images of a continuous and visually unified territory, at least within the presidencies. Maps are capable of both establishing and accentuating differences, and also attenuating and obviating diversity. If the city plans of Madras and Calcutta highlighted and visually codified new forms of social difference and hierarchical stratification, the imperial survey maps obviated diversity and diminished differences between communities, localities, regions, and provinces, and represented the land, or at least the Company's possessions of land, as a socially flat, politically uniform, and geographically stable entity, encompassing a singularity that in reality it neither possessed nor desired.

Take for instance two major projects led by the first surveyor general of the Fort William Presidency (in Bengal), Major James Rennell,—A Bengal Atlas (1781) and the Map of Hindoostan (1782)—which exemplifies how a distant land was first appropriated and made palatable to the people of the British Nation through maps, how a claim of sovereignty was increasingly represented through cartography, and how the right to pass laws were visually justified through a history of possession and ownership as represented on cartouches, dedications, ornaments and marginalia on maps.

Company Possession, Sovereign Projection, and Britannia's Benediction

James Rennell first arrived in Calcutta in 1764, and soon took up the position of Surveyor General of Bengal, a position that appears to have been created for him.Footnote 16 He began the survey of Bengal in the autumn of 1764, which would ultimately culminate in A Bengal Atlas in 1781.Footnote 17 Although appointed by Henry Vansittart, who was then the Governor of the Fort William/Bengal Presidency, it was Robert Clive, in his second tenure as Governor of the Bengal Presidency, and Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of Bengal (an expanded office), that played a critical role, along with a few others, in contributing to a visual lineage of British possession and sovereignty over Bengal.Footnote 18

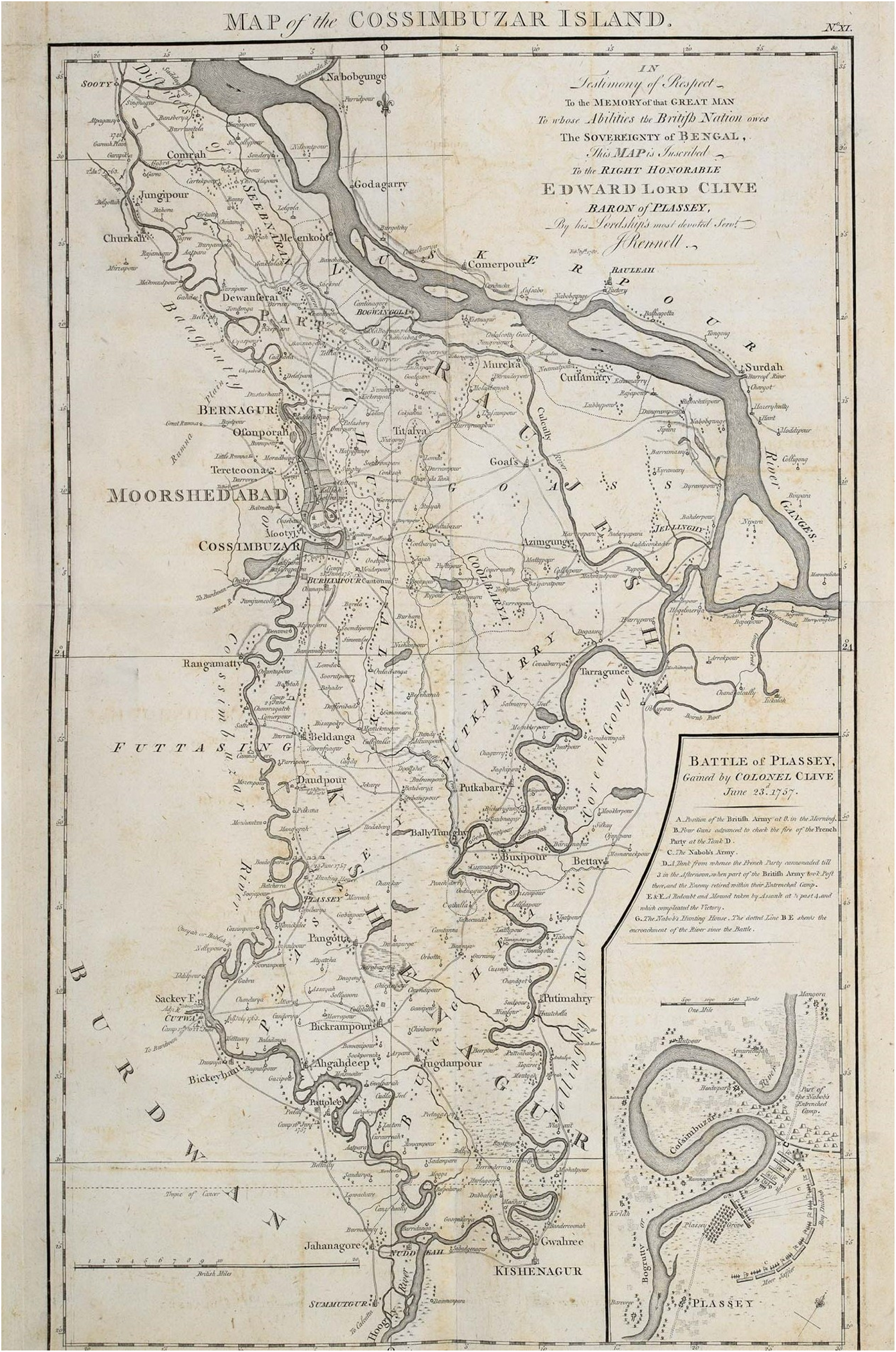

In viewing the plates of the Bengal Atlas, the viewer is also invited to follow a narrative of increasing territorial sovereignty, as the cartographic gesture of the Atlas aims to depict “a history of possession.”Footnote 19 The Atlas contains twelve plates, with each plate being dedicated through an ornamental cartouche to a high-ranking official of the Company (for instance, as on Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. “A Map of Bengal and Bahar” Plate IX, James Rennell, An Atlas of Bengal (1781). The Dedication in the top right corner reads as follows: “To The Honorable Warren Hastings Esq. Governor General of the British Possessions in Asia; This Map of Bengal and Bahar (Comprehending a Tract more extensive and populous than the British Islands) Is respectfully Inscribed. In Testimony of his Distinguished Abilities; And in Gratitude for Favours Received….” [In public domain]

Figure 2. “Map of the Cossimbuzar Island,” Plate XI, James Rennell, An Atlas of Bengal (1781). [In public domain]

In addition to the inundation of crisscrossing lines indicating provisional boundaries, the maps in the Atlas are also littered with the names of provinces, cities, towns, and villages in distinct hierarchical fonts. Rennell's elaborate surveying and cartographic practices marked a rupture, as Kapil Raj has highlighted, insofar as they made possible new forms of cartographic representations with excessively populated geographical information and even served “as a model for the future mapping of Britain itself.”Footnote 20 More significantly, for the jurisdictional context of India, they also provided a visual justification for the British assertion that “no other political entity in the past had…woven together a newly acquired territory into a continuous and conclusive image.”Footnote 21 The allure of the Atlas, for the viewer, rested on the idea that Rennell's survey was so exhaustive so as to comprehensively capture and succinctly replicate all geographical information of the land, what Sudipta Sen has referred to as “the panoptic gaze,” but it is the emblematic and ornamental features wherein the aspirational desires and ideational claims are most powerfully inscribed and directly visible.Footnote 22

Plate XI (Figure 2) is particularly unique among all the plates that comprise the Atlas given its visual depiction of an important event that marked the beginning of nearly 200 years of British control of Indian territory. The Battle of Plassey, as inscribed and depicted in detail on Plate XI (Figure 2), led to the British East India Company's decisive victory over the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud Daulah, and his allies in the French East India Company. The dedication on the same Plate credits “the Right Honorable Edward Robert Clive,” who led the army of the British East India Company against the Nawab, for “the Sovereignty of Bengal,” a sovereignty that is depicted as already secured according to this cartographic narrative. It is not the East India Company that owes to the “Abilities” of Clive in securing Bengal's sovereignty, but the “British Nation” itself, which supposedly enjoys the sovereignty, that is enjoined to revere Clive's success. The inset of the Battle depicts the chronological events of June 23, 1757—when the Nawab surrendered the Fort to Clive—by showing where the British Army stood in the morning, the position of the Nawab's artilleries, the artilleries of the French Company, and the position of the British Army in the afternoon. The viewer is invited to relive the battle through the strokes on the map that connect the British Army to the armies of the Nawab and the French Company, indicating the exchange of gunfire. In depicting this active battle, the viewer is transported back to the scene and coaxed to remember the violent founding moment of British sovereignty in India, the hard work of Britain's noble sons, and the massive victory despite all adversaries. It is pertinent to note that Bengal was not yet under the absolute sovereignty of the Crown, but it is “the British Nation” nevertheless that is motivated to celebrate the expansion of its sovereignty.Footnote 23 Although the Regulating Act of 1773, and more directly the East India Company Act, or the Pitt's India Act, of 1784, brought the Company under the supervisory control of the British Government (including all its political affairs),Footnote 24 it was not until the Charter Act of 1813 was passed that an “undoubted sovereignty” was formally ascribed to the Crown, and only in 1858, through the Government of India Act, that the East India Company was liquidated, after which Queen Victoria was legally designated as Empress of India in 1876.Footnote 25 What the viewer witnesses in Rennell's Atlas in 1781, therefore, much before Pitt's India Act of 1784 or The Charter Act of 1813 is a cartographic predecessor of the legal changes to come, as if it were visually anticipating, auguring, and awaiting the arrival of the law.

Hector Munro had won for the Company, from Shah Alam II, after the Battle of Buxar in 1764, only the right to collect revenues in Bengal, the diwani rights, and to administer related civil justice.Footnote 26 What is depicted in the cartographic narrative, however, is not just the de facto status-quo but also the de jure status that was yet to legally come. As Ian Barrow has accurately noted, although the Company “only had legal rights to the collection of revenue and the dispensation of justice…[t]he dedications [in the Atlas] created the semblance though of the Company as indeed the possessor, the rightful owner, of the territory of Bengal.”Footnote 27 The cartographic depiction here performs the function of emotively and pictorially bestowing on Britain a longer and more expansive title of ownership and control than actually existed. In cartographically endowing the British Nation with the sovereignty of India, and visually recording a violent inaugural moment in all its glory and detail, Plate XI is a crucial key to deciphering the cartojuridical operation of the Atlas, especially as it conflates the past, present and the future, rendering as already-present those legal regulations that are yet to come, and vesting the (as-yet unavailable) sovereignty of India not merely in the (as of then) monopolistic British East India company, but firmly in the hands of the British Nation in toto.Footnote 28

Viewed along with Plate IX (Figure 1), and the dedication to the “Distinguished Abilities” of the first Governor-General of Bengal, the viewer is invited to participate in the grand visual narrative of Britain's (not just the Company's) continued and unhindered possession, ownership, and sovereignty of Bengal, depicted as an uninterrupted sovereignty all the way from Robert Clive, traversing the tenures of Hector Munro (Plate III) and Harry Verelst (Plate VIII), up to the contemporaneous Warren Hastings. The dedication in Plate IX subtly performs another avaricious gesture as well. It designates Warren Hastings as the Governor-General not just of the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal, which was the office he occupied when the Atlas was created, but of the “British Possessions in Asia,” cartographically betraying an imperial desire and augurating forthcoming conquests, possessions, and expansions, and indicating that the land represented on the Plate is only a fragment of a larger (fictive) colonial holding. For in reality, as of 1781, there were not many “British Possessions in Asia,” apart from the three Presidencies in India, given that many territories were acquired later, including Ceylon (1795), Malaya (1824), Singapore (1824), and Hong Kong (1841).Footnote 29 What the viewer is informed through Plate IX, well in advance to it actually happening, is that the British Nation has aggrandized and increased its territorial foothold in Asia. The Office of the Governor-General is here cartojuridically expanded through the medium of the map in assigning to the office a fictional jurisdiction larger than what was juridically circumscribed.Footnote 30 Bengal, or India, in this visual representation, is only a metaphor for the extending and expanding sovereignty of Britain, whether factual or imagined. The inscription of “Bootan” in Plate IX is arguably part of this desire to indicate the ever-expanding reach of British sovereignty.

There is also a justification given for why Hastings possessed “Distinguished Abilities.” He was responsible for the governance of a “Tract” of land which was “more extensive and populous than the British Islands.” As such, the Atlas conveys that he possessed a jurisdictional right over an area of the earth much larger than what the Crown-in-Parliament held. What these plates, insets, dedications, and ornamentations in the Atlas indicate is that, as J. B. Harley claimed, “[i]nsofar as maps were used in colonial promotion, and lands claimed on paper before they were effectively occupied, maps anticipated empire…”Footnote 31 These plates were more than mere geographic representations. They were, as adumbrated, parchment and cartographic manifestations of larger territorial aspirations, imperial desires, and legal premonitions. It is true that at the time of the Atlas's creation the East India Company occupied and held the diwani rights to collect revenues in Bengal and engage in associated civil administration, but the sovereignty was still not under the Company, much less under the Crown or the British Nation, and legally still remained with the Mughal Emperor.Footnote 32 The Atlas here overrides existing legal arrangements to proliferate and project juridical realities of its own, beckoning the law to take heed and follow. It is such a self-contained, and independent, even opposing, juridical potentiality recorded within a map that this paper designates as a cartojuridism. Through such an overriding gesture, insofar as the map's immanent legal projections are concerned, the Atlas becomes an early colonial instance of cartojuridism in India, through which maps visually enact and imaginally perform juridical actions of its own. The Atlas, in overriding existing juridical relations and preceding the actual sovereign charter, looks forward to the extensive British Raj-to-come in Asia, beyond just India, anticipating the empire and its expansion of sovereignty, and providing a graphic and spectral legitimation, through the narrative of uninterrupted possession, to what the English Common law renders as adverse possession.

Barrow offers two speculative reasons for Rennell's expansive dedications to Company officials and the bestowal of sovereignty on the entire British Nation. First, these could well be hyperbolic representations to enjoin the people of Britain to participate in the Company's ongoing territorial conquests in India, thereby “…viewers [of the Atlas] could well indulge in a sentimental conquest of Bengal. Rennell's maps were an invitation to participate in the enjoyment of a possession…”Footnote 33 Second, the Atlas emerged at a time when the Company was facing several controversies back in the Metropole, and “…Rennell's atlas was a timely political statement” vindicating the noble work of the Company against its critics.Footnote 34 It does not seem plausible, however, that Rennell's dedications or his gesture of appropriating for the British Nation the sovereignty of Bengal, and the supposed possession of Asia, was merely a tactical or strategical gesture on behalf of the Company, given his reflections and reiterations in his Memoir, that it is “[t]he British nation [that] possesses, in full sovereignty, the whole soubah of Bengal, and the greatest part of Bahar…”Footnote 35 This assessment is retained in multiple editions of the Memoir, including the latest 1793 edition, indicating that this is a sentiment that Rennell continued to believe in and portrayed, partaking, perhaps, in the larger culture of belief and reliance, even if expectantly, in British sovereignty of Bengal. Rennell also subsequently reflected that his maps crucially contributed to understanding British “political connections” in India, providing the viewer with an explanation of “local circumstances” and the “present critical state of affairs.”Footnote 36 The maps of the Atlas, even in Rennell's own understanding, embodied a political role beyond the merely topographic, and “became synonymous,” as Sen has buttressed, “with an imperial view of political space.”Footnote 37 Furthermore, the Atlas, which preceded the legal charters and parliamentary statutes in (visually) usurping possession and sovereignty for the British nation, and coaxing the formation of the empire in Asia, was just the beginning of an incremental cartojuridical process.

The laying claim to sovereignty is a gradual process even in the visual modality of the cartograph, and such was the case even in the chronological sequence of Rennell's projects. This becomes clearer if one were to view the Atlas along with his subsequent project, titled Map of Hindoostan (Figure 3), published one year after the Atlas, wherein Britannia, the personification of the British Nation as a divine female warrior, makes a visible appearance on a cartouche (Figure 4), and is depicted as receiving into her possession a Hindu religious code (“Shaster” or shastra) in order to syncretize and revamp it as a rationally ordered systematic codification of indigenous religious laws.

Figure 3. Map of Hindoostan, by James Rennell (1782). [In public domain]

Figure 4. A closeup of the Cartouche of Britannia receiving the “shaster” from genuflecting Pundits, in James Rennell's Map of Hindoostan (1782). [In public domain]

The cartouche signifies the glory and power of the British Empire, with the British lion's foot atop the globe. Britannia's spear rests not on barren land but on “a bolt of cotton cloth,” the main Indian export to Europe.Footnote 38 The cartouche is situated in the white space of the Bay of Bengal, signifying the territoriality of the British demesne in the Indian subcontinent. The presence of the cartouche—with a list of Britain's military conquests inscribed on the pedestal, with opium poppies in its wreath above (itself next to a sword and a caduceus), the Company's ship made visible in the background, and Britannia herself appearing as a “humane Interposition,” all of which is inscribed within the confines of a cartographic depiction—signifies that there is a political and ideological argument being made through the cartographic representation, of commercial, military, spiritual and civilizational superiority.

First, in the Atlas, individual officers of the British East India Company are represented as the possessors and rightful owners of a vast territory, akin to the estate landlords in Britain.Footnote 39 Through them, the British Nation is prematurely bequeathed with the sovereignty of Bengal, and the Governor-General of Bengal is endowed with a larger jurisdictional mandate. Subsequently, in the 1782 Map of Hindoostan, it is no more the Company but Britannia herself, the prosopopoeial and mythical embodiment of the British nation, who appears as a divine manifestation and law-giving authority, with benediction and reverence, and who is cartographically represented as legitimate law-giver for the native populace, and the sovereign of “Hindoostan.”Footnote 40 Although the use of colors in the Map of Hindoostan (Figure 3) distinguishes British Possessions in India from other powers, it is only Britannia that makes a visually regal and imperial appearance on the Map, indicating at the obvious pre-eminence and superintendence that is hoped to be accorded to the British Nation.Footnote 41 As Sen has observed, “there is little in the description or depiction of British India that invokes the sovereignty of the Mughals or the marking of the passage between a Mughal and a British India.”Footnote 42 In continuity with the Atlas, what this spectral appearance of Britannia also demonstrates is a cartographic desire for an expanding and ever-increasing sovereignty of the British Nation, its civilizational superiority in being able to offer rational and systematic laws, and its military and fiscal acumen in conducting good governance and trade. Once again, on the map, there is a legal premonition of a larger system of governance. Through Britannia, the map visually engages in a rhetoric of British supremacy, enlightenment, and strength, supporting Harley's claim that maps are “inherently rhetorical images.”Footnote 43 Rennell's explanation to this emblematic frontispiece, among other details, states that Britannia's appearance is “in Allusion to the humane Interposition of the British Legislature in Favor of the Natives of Bengal.”Footnote 44 The British Legislature is cartographically accorded direct law-making power for India even before it can be granted that power by law. Yet again, the map performs a cartojuridical function in overriding existing juridical arrangements and legal powers by projecting its own orders and realities of legal relations as cartographic truth. More concretely, the map also preceded the law in the fixing of boundaries. To be accurate, it was the map which fixed the boundaries and not the law. Michael Mann informs us that it was in the Map of Hindoostan that red was used for the first time to depict British territories, a practice which Britain will uniformly develop in all of its subsequent cartographs.Footnote 45 Mann asserts that “Rennell went furthest when establishing the border colors,” as no rigid delineation of the boundaries existed as yet.Footnote 46 The red coloring on the map depicting the territories of British possessions was used by Rennell to roughly delineate the provincial borders. The juridical power of the cartograph, however, led to the gradual entrenchment of these very lines as the boundaries,Footnote 47 creating law out of image, regulation out of notation, and nomos from the line, such that the cartographic boundary “now gained the function of defining the British position and slowly became the “exact” definition.”Footnote 48

What is textually inscribed on the Atlas, that it is the British Nation that possesses sovereignty in Bengal, is now transferred visually to a divine and mythical being that represents the British Nation viscerally. Crucial in this cartographic transition, this sovereign expansion, is a cartojuridical sleight of hand wherein the sovereignty that the British Nation now apparently holds, by virtue of Britannia, is no more just of Bengal, but of the whole territory of India, graphically demonstrating that Britain is gradually, but surely, inching towards establishing sovereignty over other parts of Asia, if not the entirety of it. Like the Atlas, the viewer of the Map is visually invited to revere Britain's military prowess, for the cartouche displays Britannia standing over a pedestal, on which is inscribed a list of Britain's military victories, presumably beginning with Plassey and Buxar, pointed out by a sepoy to his colleague. Insofar as cartographic narratives can be discerned, the Atlas of Bengal and the Map of Hindoostan work together to proliferate a sustained view of continued British possession of land, sovereign power, and law-giving authority in India.

What makes this cartouche particularly intriguing is that such ornamental and elaborately decorative cartouches—which emerged as strategical ways to cover over empty spaces and conceal geographical ignorance of an area—began to wane out of popularity in the eighteenth century, and were rapidly discontinued as a practice, especially in its final decades.Footnote 49 There are varying opinions for this decline. Mary Pedley believes that it was an effect of the French Revolution, due to which royal and noble patronage to géographes du roi (royal geographers) ceased.Footnote 50 George Kish has argued that the decline was more a result of the Napoleonic Wars, as maps became more functional and utilitarian.Footnote 51 Matthew Edney diverges from such emphases on revolutions and wars and argues that the decline was brewing for the most part of the century, culminating towards the turn of century as a result of increased enlightenment based cartography.Footnote 52 In any case, whichever diagnosis the reader finds compelling, what remains true of cartouches in the latter part of the eighteenth century is that, in the words of Duzer, “…if a cartographer placed an elaborate cartouche on a map it was either for a very specific purpose, or else he or she was indulging a somewhat archaic style.”Footnote 53 Rennell's cartouche, in stepping out of the contemporaneous cultural milieu of cartography, is not just indulgent in an archaic style but intended for the specific purpose of renewing and expanding the cartojuridism of the Atlas. The crucial indication arises from the fact that the cartouche is laid over the empty space of the Bay of Bengal, and as such is not concealing any topographic information of land, which was the conventional purpose of cartouches. In other words, it takes on an avowedly political—not merely a utilitarian—role, and as Harley has exhaustively shown, “decorative title pages, lettering, cartouches, vignettes, dedications, compass roses, and borders, all of which may incorporate motifs from the wider vocabulary of artistic expression, helped to strengthen and focus the political meanings of the maps on which they appeared.”Footnote 54 In fact, Britannia's receipt of the “shaster” was directly related to contemporaneous developments of the Company's legal policy in India.

Warren Hastings, in the preceding decade, enacted the Judicial Reforms Plan of 1772 that ushered in some of the first codifications in India over the next couple of years.Footnote 55 Hastings's Plan called for translations and codifications of Hindu and Muslim personal laws for the benefit of the colonial administrators and judges in resolving civil disputes in Bengal. This was an ongoing project at the time of Rennell's survey, with the first such codified text, translated from Sanskrit to English, A Code of Gentoo Laws; or, Ordinations of the Pundits by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, being published in 1776. More notably, this systematic effort at translations and codifications, which led to the agglomeration of a corpus of “laws of the Hindoos,” received legal recognition for Court procedures through The Administration of Justice Regulation passed by Hastings in 1780, two years before the Map was published.Footnote 56 As such, Rennell's cartouche remarkably illustrates how cartography engages with and implicates contemporary legal processes. Moreover, by actively participating in concurrent legal developments—for the codification of the “Shaster” and its use in the colonial judiciary were contemporaneous with the cartouche—the map instils itself as a juridical text that not just anticipates sovereignty and law but also provides visual support in the sustenance and proliferation of legislations and regulations. Rennell's Map and Atlas get firmly entrenched as parts of the cultural representations of colonial law and policy, in addition to its constitutive function of jurisdictional ordering and juridical restructuring. “Rather than being inconsequential marginalia,” as Harley noted, “the emblems in cartouches and decorative title pages can be regarded as basic to the way they [maps] convey their cultural [and political] meaning[s], and they help to demolish the claim of cartography to produce an impartial graphic science.”Footnote 57 Harley's claim is evinced in the cartographic operations of the Company. For, in acclaiming sovereignty, instituting territorial boundaries, expanding juridical offices, depicting an uninterrupted possession of territory, visually appropriating more territorial possessions, and supplementing juridical developments, the Company's cartographic practices and representations played an integral part in its concomitant legal and political affairs.

Lines of Color, Colorful Lines, and the Cartographic Creation of the Other

Early British maps also functioned as visual means of ordering space hierarchically, recreating and sustaining specific forms of social relations, and instituting new forms of nomos. In another presidency of the Company, one further south, maps were created in the early eighteenth century which, for the first time anywhere in the world, depicted the colored division of a city into “White Town” and “Black Town.” As Carl Nightingale has argued, The Presidency of Fort St. George, in Madras, contained “the first instance in world history of an officially designated urban residential color line.”Footnote 58 The 1726 Plan of Fort St. George and the City of Madras (Figure 5), commissioned by the former Governor of Madras, Thomas Pitt, is the earliest surviving map that depicts this colored division of the city, much before its insidious parallel across the Atlantic. The viewer is introduced to the southern Fort of the British East India Company and its surrounding city, divided by bulwarks, fences, and parapets. There is a wall running across White Town, and a relatively smaller wall that also runs across Black Town, both walls having long and tenebrous histories.

Figure 5. A Plan of Fort St. George and the City of Madras (1726), commissioned by Governor-General of the Presidency, Thomas Pitt. [In public domain]

The White Town in the Plan, also referred to in the records as the “Christian Town” or the European Town, depicts the most important government and judicial buildings of the city, including the Governor's House and the Choultry (courthouse), multiple churches, and the residences of the officers of the Company as well as of other European settlers. The Black Town, also referred to as the “Gentue Town” in the records, depicts the living quarters, business houses, and other establishments of the much larger native population of Madras.Footnote 59 Eponymically, the city was divided according to color, but also according to religion (Christian vs Gentue), which was an originary theme of western racism and colonialism here represented as a cartographic mark of civilizational difference.Footnote 60 The map becomes the parchment site on which the complex “race-religion constellation,” as Anya Topolski has framed it, gets a second reality on text, which visually entrenches and essentializes artificial attributes of civilizational, colored, racial, and religious difference as innate and seemingly permanent.Footnote 61 The “Mutial Peta,” or the “The New Black Town” comprised a number of gardens and establishments by urban artists, and the Comer Pete Town encompassed the main trade market and commercial street, The Great Buzar and The Buzar Street.Footnote 62 The icons on the Plan exemplify well Harley's understanding that cartography's guiding “rule seems to be ‘the more powerful, the more prominent,’” as can be discerned from a comparison of the two prominent churches.Footnote 63 St. Mary's Church (characterized as “The English Church”), receives a notation of a much larger spire than St. Andrew's Church (inscribed as “The Portuguese Church”), although the spire that substantially increased the height of the former was introduced only towards the end of the century. A clear visual representation of the pre-eminence accorded to the first Anglican Church in Asia, and arguably in the East of the Suez, what was referred to as “The Westminster Abbey of the East,” and where Robert Clive and Elihu Yale held their wedding ceremonies. Two, out of the three, Pagodas depicted on the map, which do not have any corresponding entries in the Remarks, are two courtyard structures in the Comer Pete Town, calligraphically stylized as “Allingals Pagoda” and “Loraines Pagoda,” referring to the extant and famous Ekambareswarar Temple and Bairagimadam Temple, respectively, in Chennai. It is perhaps indicative that in visually representing these particular pagodas, of the numerous that existed in Madras, historically dubbed as “The City of Temples,” what is being signified is that loyalty to the Company will be well recognized, and favors returned, given that the founder of the Ekambareswarar Temple, Allanganathan Pillai, was a chief merchant of the Company's Madras Factory, and was a loyal ally and a trusted subsidiary.Footnote 64 Similarly, the founder of the Bairagimadam Temple, Ketti Narayan, belonged to a family of chief merchants to the East India Company, and whose father, Beri Thimappa, was a chief merchant and dubash (agent) for the Company.Footnote 65 The pagodas that are considered worthy of representation in the Plan are, among many others, mainly those that can be linked and considered to be beneficial to British commercial interests.

Another function of the map is to visually endow a hierarchy of places of burial. It appears that the cartograph establishes stratified orders of social reality pertaining not just to birth and life, but also to death, constituting an idiosyncratic form of spectral politics in the cartograph, as can be discerned from the Remarks apropos the places of burial. The map depicts, and the Remarks indicate, the various sites of burials, including the “Pagans Burying Place” and the “Jewish Burying Place” in Comer Pete Town, the “English Burying Place” in the Black Town, and the “Armenian Burying Place,” the “Portuguese Burying Place,” and the “Moors Burying Place” in the Mutial Pete. Pertinent to note that the term “place of burial” is inaccurate, insofar as the native population is concerned, given that most native castes engaged in cremation as funerary ritual. The Plan, however, rectifies the error in the Remarks by correctly inscribing “The Place where the Indians burn their Dead” on the site corresponding to the remark. An error, perhaps, resulting from an overlooking of those things considered as not as important relatively. In any case, what the map intends to perform is a social othering and reconstitution of hierarchy. For while European identities are neatly classified based on country of origin, English or Portuguese, the natives are lumped together and designated with the all-too-familiar classification as the “Pagan” other. This should not come across as particularly surprising, for the Black Town, or “Gentue Town,” was also subject to the other famous othering strategy of designating people as “genteel,” but what is remarkable about the map is that it visually lays down claims of first priority and superiority. In depicting a single place of burial as the place of cremation of all the “pagans” in the city, the map dilutes the demographic differences that existed and which ordered indigenous social and cultural traditions. For in reality, Madras, and South India in general, was a highly stratified society in the early eighteenth century, divided on the basis of caste. People of the Left-hand castes, (idangai) were often in an antagonistic, rather than agonistic, relationship with the people of the right-hand castes (valangai).Footnote 66 The dual classification, however, as Arjun Appadurai has argued, blurs the further sub-stratifications and nuances that comprised the caste system of the early eighteenth century.Footnote 67 In any case, as Vikram Harijan notes, the precise place to cremate the dead were one of the sources of considerable conflict between various castes in the early eighteenth century, indicating the multiplicity of burial, or cremation, grounds for the native population.Footnote 68 In reducing the actual geographical distribution, flattening the cornucopia of places into a few, and emphasizing personal predilections on a Plan, whether of Churches or places of burial, the map becomes the nomoscapic medium of instituting a new nomosphere for the city, impressing alternative desires and realities of social ordering, and cartographically ushering in and establishing preferred ideologies.Footnote 69 Intriguingly, the White Town contains no place of burial, for the English Burying Place is situated within the Black Town, outside the fortified confines of the White Town. There might be a specific reason for this urban design, intended to mark a radically visible social distinction between the White and the Black Towns.

As can be glimpsed from the stark variation in the fencing and boundary of the White Town vis-à-vis the Black Town in the Plan, the two areas were intended to be perceived in starkly contrasting ways. It appears that the walls were predominantly similar in both the towns at least until the mid-seventeenth century. It was in the mid-1650s that a second, stronger, bulwark was erected around the White Town, “which formed a much larger trapezoidal perimeter around the whole European settlement, enclosing what was then called ‘Christian town.’”Footnote 70 The White Town contains no place of burial considering that the intended affect of the architectural and urban layout of the White Town was to elicit a perception of English, or European, might and “commanding superiority.”Footnote 71 As Nightingale has elaborated, “[t]he architecture of the European section radiated might: parapets and cannons festooned the roofs of the walls, gates, and houses. By the eighteenth century, most buildings in White Town were plastered with chunam, a substance made from the crushed shells of a local mollusk, which gave exteriors a marble-like appearance and from out at sea made White Town shine whiter—literally—than Black Town.”Footnote 72 In this drive to architecturally depict purity and a might of superiority, to literally whitewash a part of the city, a place of burial is a black stain on the otherwise white aspiration. When one entered the City of Madras, especially by sea, one was to be subjected to nothing but grandiosity and greatness, pompous palatial buildings and eclectic European architecture, inoculated by bulwarks and canons, replicating the finest of British tastes, Victorian predilections, and European military power in a faraway land, perhaps motivated by what Barrow has identified as “the nostalgia for ‘home’” among the British in India.Footnote 73 This intended first impression, the primordial affect, the inaugural gaze, is captured well in an early eighteenth century oil canvas portrait of the White Town (Figure 6).

Figure 6. “Fort of St. George on the Coromandel Coast, Madras, belonging to the East India Company of England,” Date estimated: (1712–1760). [Reproduced with permission from the British Library]

The White Town in Madras is conventionally depicted, as on Figure 6, as a stronghold of British power, with the Union Jack flying high, and canons on parapets lined up on the top of strong bulwarks. Merchant ships, with smoke puffing and flags hoisted, sail towards this flourishing port of trade. The intended alluring effect of the White Town is assiduously captured in this portrait, with towers, spires, and palatial houses set against a backdrop of a scenic vista of rolling hills. The Proclamations of the Governor were traditionally issued to the sound of canon shots from the towering walls of the White Town.Footnote 74 The Black Town is hidden from sight, as intended, in portraits, and when portrayed (as on Figure 7), it is depicted as the place outside the legitimate city, from where the natives look up to the soaring domes and towers of the White Town.

Figure 7. Black Town, as depicted in Plate 8 from the second set of Thomas and William Daniell's “Oriental Scenery” (1797). [Reproduced with permission from the British Library]

As stated earlier, the cartojuridical operation as manifested in the 1726 Plan—quite differently from the other instances examined so far—is one of representing and establishing social hierarchy, which needs to be understood as related to nomos.Footnote 75 In a crucial sense, the neologism of cartojuridism aspires to delineate the affects of the map not just on law and legality positively understood, such as in chartering and claims-making, sovereignty and possession, and jurisdiction and territoriality, but also in the establishing or entrenching of social conventions, customary rules, and spatial regimentations, as exemplified in the Madras Plan. For before the publication of the map, the term “White Town” was found in only one other “isolated incident” in 1693.Footnote 76 The town occupied by the Europeans was predominantly referred to as the “Christian Town” and everything surrounding it as the “Gentue” town. It was Thomas Pitt's map that cemented the division as one based on color, “after which ‘White Town’ took over as the most widely used designation.”Footnote 77 In visually entrenching nomospheric attributes to the city, the Plan becomes a stellar instance of how maps not just anticipate sovereignty, expansion of territory, and legal relations, as witnessed in Bengal, but also how they visually (re)produce and entrench social orders and categories of division.

The Plan of Madras also inaugurated a tradition of representational politics, for another map in Calcutta, the 1842 SDUK Map (Figure 8), seems to have carried on the tradition of representing only those places of British interests, visually rendering cities as absolutely British in character and structure. The Map was published by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (S.D.U.K), a London based foundation intended to diffuse information and knowledge to British working and middle classed citizens who could not afford or access formal teaching and education. It is worth scrutiny as to what cartographically passes for useful, and what is neglected as useless. In a more extreme manifestation of the Madras Plan, the List accompanying the SDUK Map provides a tabulation of important Government and Public Institutions, Churches and Chapels, but not of temples, mosques, or Pagodas whatsoever. Viewers are informed, through the tabulation, on what streets one could find The Supreme Court and the Town Hall, The St. James Church and the St. John's Cathedral, The Police Office and the General Treasury. In listing the streets where “useful” buildings are located, the viewer is invited to enter the map and navigate the British streets of Calcutta, cartographically transporting the London viewer across the continent to witness the exuberance of the Company's Fort William. The Fort itself is visibly humungous, jumping out of the map as a pinkish lotus-like structure, consisting of the Governor's House, the Grand Jail, and the royal Esplanade. If the Madras Plan of 1726 at least depicted some temples and pagodas, the Calcutta Map of 1842 does away with that requirement entirely. Indians are no more native inhabitants of the city, for as the vignettes of the Government Building, Writers’ House, and the Esplanade Row at the bottom of the map portray, they are domestic servants and city workers, at best, who are marginalized and banished to the outskirts of the city, much like Madras, from where they look inwards to the magnificence and marvel of British architecture, accoutrements, and appurtenances.

Figure 8. Map of Calcutta, published by S.D.U.K (1842). [In public domain]

In the colored division of Madras, with its accompanying icons and remarks, and the portraits of White and Black Towns, as well as more directly in the SDUK Map of Calcutta, and its accompanying listings and vignettes, the maps play a function of visually and radically recreating and re-establishing the cities as monolithically British, Christian, and Victorian. As Barrow has argued apropos the SDUK Map, but which is equally fitting in the Madras context, the cartographic gesture in operation here is the “extrusion of indigenous peoples from colonial maps…Apart from the depiction of Indians as porters and peasants, there is little indication in the map that Calcutta was an Indian city inhabited by Indians.”Footnote 78 The legal subject is cartographically rendered as primarily, if not only, British, who administer, operate, and utilize the government and judiciary, the recreational parks and theaters, the markets and bazaars, and the churches and chapels. This invisibilization is also a cartojuridical technique of creating subjectivity in particular manifestations and forms. If James Rennell's cartouche in the Map of Hindoostan depicted the native subject as a genuflecting subjectivity, anticipating and praying for Britannia's legal acumen and the British Legislature's rationality, the SDUK Map and the Madras Plan have banished the native subject outside the functional space of the city, which the Indian can access only as servant and not as a rights-bearing subject.

A Concluding Note on Cartojuridism

This paper has attempted to demonstrate how maps are related to law, broadly construed, in myriad ways. While similar relations are gradually being explored in other jurisdictional contexts, this paper's primary focus was on the early cartographic practices of the East India Company, which have been predominantly neglected from a legal perspective. The Bengal Atlas and the Map of Hindoostan proliferated their own expectations of British sovereignty and augured laws yet-to-come. The Plan of Madras and the SDUK Map of Calcutta depicted and ordered aspirational realities, thereby imaging and paving the way for the entrenchment of ideologies of color, religion and race on social space. What is revealed in these instances is that a map ought not to be considered as just an innocuous geographical representation of a stable and objective reality “out there,” because it can also be, and has historically been, an agent of change and transformation, affecting and transmogrifying the reality. To return to the epigraph that this paper began from, the simulacra precedes the simulation. Baudrillard's thesis also works to radically shift the fulcrum that moves Jorge Louis Borges's narrative in On Exactitude of Science (1946), where the imperial map spread like a carpet over the earth, covering every inch of land. Contrary to the Borgesian perfect map that is laid over the territory, it is the territory that is modeled according to the Baudrillardian map. The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it. It is nevertheless the map that precedes the territory. As Bernhard Siegert has elaborated, maps are not merely “representations of space” but are “spaces of representation,” where the representation becomes the model for the reality “out there.”Footnote 79 In the context of India, this is most directly evinced in the colored lines of Rennell, where the tentative inscription of boundary lines, as opposed to being representations, fueled the juridical institution of the boundaries, continuing the tradition that Cornelia Vismann hinted at when she claimed that the drawing of the line inaugurates a new nomos. In a crucial way, these colored lines on the Map, the dedications of the Atlas, the visibilities and invisibilities of the Madras Plan and the SDUK Map, the cartouche of Britannia, the Battle of Plassey, and the colored segregation of cities, all point to the varying jurisdictional, juridical, and sociolegal functions of a map. The map, as a legal text in its own right, becomes the preceding simulacra that assiduously converts land into territory, based on unificatory images that visually depict the coalescence of sovereignty, and upon which jurisdictional claims of right and recht and interminably sanctioned. As Peter Goodrich has argued, “For lawyers, historically, the map is…an expression of sovereignty, a specific and particular aesthetic of hierarchy and governance whereby the measured space and chorographic description of place is a manner of imposing political power onto the land… The map as legal device is a charter that both inscribes the name of the sovereign or nation on the imperium, the parchment empire, and in doing so indicates a measured correspondence of the cartograph to lex terrae—the law of nature, custom, and use, inscribed in the very matter of the earth.”Footnote 80

Legal scholarship has not sufficiently engaged with maps, although historically it was cartography that circumscribed territory and made possible a jurisdictional ordering in different historical contexts: whether in the creation of Roman boundaries, the Bedolina distributions, in the delimitation of a Northern Ireland, the carving of a new Siamese geo-body, the distant legal claims-making on the American mainland, the jurisdictional authorization of the Australian hinterlands, the divisions of Africa according to the Berlin Conference, the unification of an imperial territorial image in Bengal, the division of the world according to the Treaties of Tordesillas and Saragossa, or in the distinction between slave-owning states and free states through the Mason-Daxon line. It is this idiosyncratic potential for creation, and the visual performance of substitution, that is designated with the term cartojuridism. It is a juridism that is cartographic, a cartography that is juridical in method and affect, and as such cartojuridism is the means by which maps accomplish a number of easily overlooked operations including imagining and creating territory and jurisdiction, anticipating sovereignty, instituting boundaries and auguring laws yet to come, conceptualizing and/or entrenching specific forms of social hierarchy and political relations, substituting itself for the reality out-there, and producing a visually unified, pacified, and stabilized space upon which law can assert its dominance and fuse with the land.

Acknowledgements

Peter Goodrich, who read earlier versions of this work and provided incredible encouragement, inspired my interest in cartography. Piyel Haldar's advice at multiple stages greatly refined and sharpened the argument. Epistolary exchanges with Ian Barrow, who kindly sent across his book, were of tremendous help in navigating the archives. Swethaa Ballakrishnen, Fabian Steinhauer, Simon Stern, Adeel Hussain and Peter Rush read earlier versions of the manuscript and shared constructive feedback on revisions. Lucy Chester shared excellent comments and cartographic insights. This research was first supported by the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory and then by the National University of Singapore's Faculty of Law. At MPI, Stefan Vogenauer and other researchers on “Legal Transfer in the Common Law World” provided a hospitable and highly conducive home for research. Conversations with fellow visiting postdocs revealed new sites of inquiry. At NUS, Benjamin Goh's and Kevin Tan's astute observations were invaluable in revising the work. This research was presented at MPI's Common Law Seminar, Cambridge University's Legal and Social History Workshop, and a workshop on “Writing the History of Empires” at the Phillips University of Marburg, and I thank everyone who attended and engaged with earlier drafts. Gautham Rao provided excellent editorial advice and I thank the three anonymous reviewers for their comments. All mistakes and omissions remain mine.

Competing interests

None.