Chapter 6 empirically demonstrates the benefits to judges of denying first-attempt divorce petitions. In this chapter, we will see the full extent to which hell-bent judges did not let anything – not even domestic violence – stand in their way of reaping those benefits. Their rulings were often legally preposterous but institutionally sensible. They were legally preposterous because they so flagrantly flouted basic tenets of Chinese family law (Chapter 2). At the same time, however, they were institutionally sensible owing to countervailing institutional forces reviewed in Chapter 3: a political ideology that ascribes the realization of social harmony and stability maintenance to the strength and health of the family; performance evaluation systems that reward judicial efficiency and punish social unrest; and the cultural logic of patriarchy that diminishes the moral worth of women and the credibility of their legal claims. Preceding chapters lead us to expect that law is not the sole or most important influence on Chinese judicial decision-making in general and in divorce trials in particular. Qualitative findings I present in this chapter bear out our expectation that the institutional logics driving judges’ divorce decisions have at least as much to do with extralegal forces as with the law itself.

Studies of intimate partner violence and policy responses focus not only on the direct perpetrators, primarily husbands and boyfriends, but also on the judges who discount and thereby enable it (Reference Epstein and GoodmanEpstein and Goodman 2019; Reference Lazarus-BlackLazarus-Black 2007). The empirical focus of this chapter is judges’ holdings in adjudicated divorce cases. A holding (理由) refers to the section of a written court decision containing the court’s grounds or rationale for its verdict (判决).

I have two tasks in this chapter. First, I establish the pervasiveness of domestic violence allegations in divorce trials. Second, I qualitatively document the strategies judges deployed to circumvent fault-based divorce standards and reap the professional benefits of the divorce twofer. Judges downplayed the seriousness of abuse. They denied that spousal battery rose to the level of domestic violence. They tried to convince women of their abusers’ love and remorse. They portrayed abuse as isolated incidents from which regretful perpetrators grew to be better people. They negated the legal culpability of abusers. They recast domestic violence as ordinary family disagreements caused by poor communication skills. And they offered relationship advice to abuse victims.

In their divorce petitions, plaintiffs often supported with evidence their fault-based claims that marital affection had already broken down beyond repair owing to domestic violence. Judges overwhelmingly quashed such claims, responding along the lines of, “Oh, he didn’t break the law, he just got a little upset. You’re overreacting. You may think your marriage is dead, but it is merely wounded. You can rebuild a happy marriage if you just try a little harder.” Holdings such as these – universally issued by every basic-level court in Henan and Zhejiang – are equal parts farce and travesty.

Judges’ rhetorical strategies were the very essence of gaslighting (Reference SweetSweet 2019). Abusers commonly turned the tables on their victims. They reframed and redefined domestic violence as just a normal part of marriage. They claimed their victims’ injuries were deliberately staged or accidentally self-inflicted. By supporting abusers’ (mis)representations of reality, “institutional authorities sometimes become unknowing colluders in gaslighting tactics, setting women up for further violence and loss of credibility” (Reference SweetSweet 2019:867). Profoundly at odds with the legal meaning of domestic violence and female abuse victims’ own understandings of what brought them to court were the revisionist, gaslighting narratives of their husbands, their family members, and judges.

Judges Commonly Faced Domestic Violence Allegations and Routinely Ignored Them

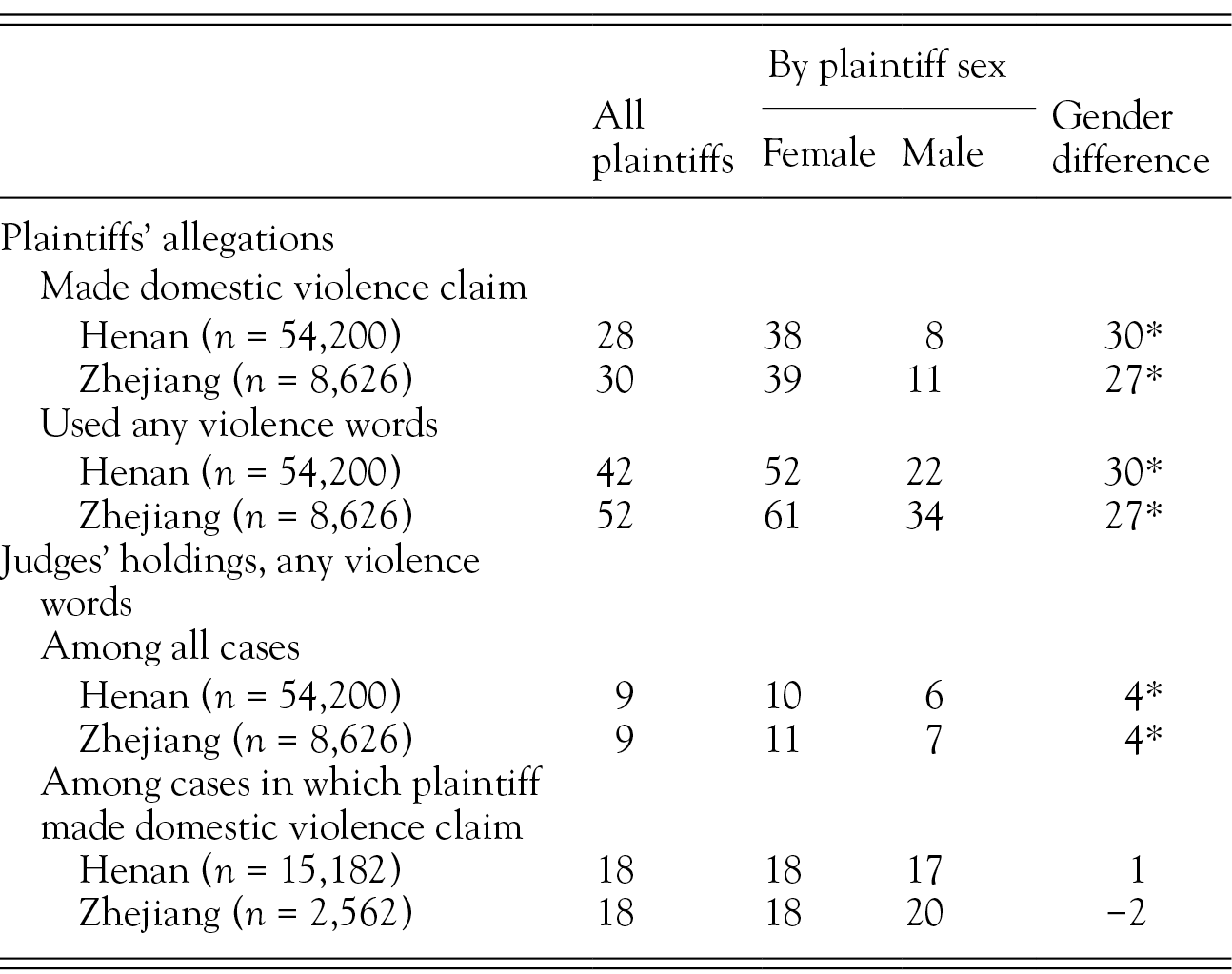

Let me first establish the sheer prevalence of domestic violence allegations before demonstrating their unimportance to judges. My measure of domestic violence claims detailed in Chapter 4 is consistent with previous estimates cited in Chapter 1: about 30% of all plaintiffs (most of whom were women) and almost 40% of female plaintiffs alleged domestic violence. As Figure 7.1 shows, rates at which female plaintiffs in my samples made claims of domestic violence – 38% in Henan and 39% in Zhejiang – are consistent with previously published estimates. Figure 7.1 also shows that allegations of abuse were consistent across rural and urban courts, although male plaintiffs’ likelihood of making abuse claims appeared to increase slightly with urbanization. Given that women accounted for two-thirds of all plaintiffs in both samples, these estimates, if accurate, mean that a full one-quarter of all first-attempt divorce petitions were filed by women making domestic violence allegations.

Figure 7.1 Proportion of plaintiffs (%) making domestic violence allegations

Note: n = 54,200 and n = 8,626 first-attempt adjudicated decisions (granted or denied) from Henan and Zhejiang, respectively. All sex differences are statistically significant (χ2, P < .001). Panels A and B are smoothed with moving averages. For more information on scatterplot points, see the note under Figure 4.5.

Also consistent with previously published estimates, 90% and 87% of plaintiffs in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively, who made abuse claims were women (Reference Chen and DuanChen and Duan 2012:29–30; Reference Htun and Laurel WeldonHtun and Weldon 2018:49; Reference LiLi 2015b:168, 171; Reference Runge, Goel and GoodmarkRunge 2015:32; Reference ZhangZhao and Zhang 2017:193–94). My estimates of roughly 10% of domestic violence claims made by male plaintiffs in both samples were probably inflated owing to at least two sources of false-positives. First, my measure undoubtedly captured some domestic violence allegations made by female defendants in cases filed by men. Second, my measure also captured some instances of male plaintiffs alleging that they had been beaten by in-laws (e.g., Decision #270158, Shangqiu Municipal Liangyuan District People’s Court, Henan Province, July 10, 2009, and Decision #107262, Shangcheng County People’s Court, Henan Province, August 6, 2009).Footnote 1 Estimates of the incidence of domestic violence claims among female plaintiffs were self-evidently less prone to such false-positives.

My next task was to compare how plaintiffs and judges talked about domestic violence. Female divorce-seekers presented allegations of domestic violence in gruesome detail and meticulously documented them with evidence. They reported all manner of weapons used against them, including cleavers, fruit knives, daggers, single-blade knives, folding knives, switchblade knives, long knives, machetes, scissors, sickles, hatchets, axes, pickaxes, trowels, hammers, shovels, pipes, rods, benches, folding stools, and so on. They reported getting stabbed, cut, and hacked. They reported being choked, strangled, suffocated, and burned. They reported bone fractures, ruptured eardrums, broken noses, and concussions. They reported sexual violence. Women rarely used the word for “rape” (强奸), much less the terms “sexual violence” (性暴力) and “sexual maltreatment” (性虐待). They more often used various euphemisms for unwanted sexual intercourse (强迫性交, 强行发生性关系) or even euphemistic references to sex (e.g., “marital life,” 夫妻生活) in which duress must be inferred by context. Copious alcohol consumption emerged as a perennial theme in domestic violence allegations. They recounted thoughts of suicide and failed suicide attempts, and even instances of being goaded by their husbands to commit suicide. Beyond reporting the occurrence of physical violence, they also reported threats of violence and even of murder, not just against themselves but also against their family members. And they documented their allegations with police reports, hospital records, photographs, transcripts of text messages, and apology letters.

Table 7.1 contains the same estimates of the incidence of plaintiffs’ domestic violence allegations (“made domestic violence claim”) that we already saw in Figure 7.1. I also considered a more extended set of words and terms that plaintiffs used in association with allegations of domestic violence. In Table 7.1, “any violence words” refers to the incidence of selected words and terms used by plaintiffs in divorce petitions containing allegations of domestic violence. They are not limited to words and terms with overt meanings of violence but also include those with bearings on and connotations of violence. “Violence words” consist of the following 57 Chinese words and terms: “battery” (暴力, 家暴, 殴打, 动手, 打骂, 非打即骂, 毒打, 大打出手, 拳打脚踢, 拳脚, 暴躁, 粗暴); “maltreatment” (虐待); “injury,” “contusion,” “bruises,” “bone fracture,” “choke,” “knife” (打伤, 受伤, 骨折, 挫伤, 遍体鳞伤, 掐, 脖子, 刀); “torture,” “suffering” (折磨); “temper” (脾气); “verbal abuse” (谩骂, 辱骂, 侮辱); “threats” (扬言, 威胁); “suicide” (自杀); “aggravation,” “intensification,” “escalation” (变本加厉); “forced” (被迫, 强行); “alcohol intoxication” (喝酒, 酒后, 酗酒, 嗜酒); “odious habits,” “incorrigible” (恶习, 恶劣, 屡教); “terror” (恐惧, 恐吓); “endure,” “intolerable” (忍让, 忍受, 忍气吞声, 忍无可忍); “medical treatment” (住院, 医院, 治疗, 医疗费, 医药费); “sought police help” (报警, 派出所, 公安局); “machismo,” “patriarchal” (大男子, 重男轻女); and “promised to change” (保证书, 承诺). The first nine words and terms on this list are those that are also used in my measure of domestic violence allegations (see Chapter 4). In the Henan and Zhejiang samples, 42% and 52%, respectively, of plaintiffs’ petitions contained at least one of these violence words. Gender gaps in both the incidence of violence words and the incidence of domestic violence allegations were identical.

Table 7.1 Proportion of plaintiffs’ petitions and judges’ holdings (%) containing domestic violence language

| All plaintiffs | By plaintiff sex | Gender difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||

| Plaintiffs’ allegations | ||||

| Made domestic violence claim | ||||

| Henan (n = 54,200) | 28 | 38 | 8 | 30* |

| Zhejiang (n = 8,626) | 30 | 39 | 11 | 27* |

| Used any violence words | ||||

| Henan (n = 54,200) | 42 | 52 | 22 | 30* |

| Zhejiang (n = 8,626) | 52 | 61 | 34 | 27* |

| Judges’ holdings, any violence words | ||||

| Among all cases | ||||

| Henan (n = 54,200) | 9 | 10 | 6 | 4* |

| Zhejiang (n = 8,626) | 9 | 11 | 7 | 4* |

| Among cases in which plaintiff made domestic violence claim | ||||

| Henan (n = 15,182) | 18 | 18 | 17 | 1 |

| Zhejiang (n = 2,562) | 18 | 18 | 20 | −2 |

Note: Limited to first-attempt adjudications. Slight discrepancies between numbers in the “gender difference” columns and numbers from which they were derived in the “by plaintiff sex” are due to rounding error.

Despite the prevalence of violence words in plaintiffs’ legal complaints petitions, they were conspicuously scarce in judges’ holdings. Violence words appeared in 52% and 61% of female plaintiffs’ divorce petitions in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively. At the same time, they appeared in only 10% and 11% of judges’ holdings in cases filed by women in the two respective samples. Even when plaintiffs made domestic violence claims, judges refrained from using violence words in their holdings. Among all cases in which plaintiffs made allegations of domestic violence (100% of which, by definition, contain violence words), judges used violence words in only 18% of their holdings. In short, judges seldom acknowledged, much less validated, plaintiffs’ claims of domestic violence. They addressed violence in fewer than one in five domestic violence cases. Of all first-attempt divorce petitions containing domestic violence claims, judges granted fewer than 2% on this basis.Footnote 2 As we will see, when judges did address domestic violence claims, they invalidated them. If everything we knew about domestic violence in China came from judges’ divorce holdings, we would come away with the impression that it was exceedingly rare, even among China’s most acrimonious marriages, and that marital discord was largely a matter of ordinary misunderstandings between well-intentioned spouses who were capable of reconciling and whose marriages should therefore be preserved. Silence and misrepresentations of domestic violence were central judicial gaslighting strategies.

Plaintiffs in divorce trials generally did not fit the profile of hapless, passive victim (Reference LiLi 2015a:147). On the contrary, initiating divorce proceedings reflects self-advocacy and agency. Many litigants knew and asserted their legal rights. Undoubtedly, some litigants acquired legal knowledge from “little experts” – divorcees who shared knowledge gained from experience (Reference GallagherGallagher 2006).Footnote 3 In particular, plaintiffs frequently invoked language from the SPC’s 1989 Fourteen Articles, which calls on judges to “conduct a comprehensive analysis of the marriage’s foundation, postmarital affection, grounds for divorce, the current state of marital relations, reconciliation potential, and other aspects when determining whether marital affection has indeed broken down.” Many plaintiffs, even those without legal representation, cited chapter and verse of the Fourteen Articles by claiming a weak “marital foundation” and a lack of “reconciliation potential” in their efforts to persuade judges that mutual affection had broken down. The term “marital foundation” (婚姻基础) in the Fourteen Articles refers to how well the couple knew each other and to the strength of their relationship before marrying. Plaintiffs commonly used this term when claiming they “did not know each other well before marrying” (婚前缺乏了解), “married in haste” (草率结婚), came to know the true nature of their spouses only after it was too late, and thus “failed to build marital affection after marriage” (婚后未建立起夫妻感情), which in turn made it “difficult to live together” (难以共同生活). Each one of these expressions appears in Article 2 as grounds for affirming the breakdown of mutual affection. “Reconciliation potential” (和好的可能) refers to the future possibility of repairing marital damage and restoring marital harmony. To underscore the futility of reconciliation, plaintiffs often asserted that their marriage “existed in name only and was dead in reality” (名存实亡). Plaintiffs also made claims of specific durations of marital separation in their efforts to persuade judges that they satisfied the physical separation test stipulated by the Fourteen Articles (Article 7). Most notably, plaintiffs claimed to have met the breakdownism standard insofar as reconciliation potential had been shattered by the defendant’s domestic violence. Plaintiffs spoke the language of faultism in their efforts to establish the breakdown of mutual affection. Their claims that mutual affection had broken down were often grounded in defendant wrongdoing.

We will see in this chapter that plaintiffs’ legal knowledge and agency were largely for naught. Defendants and judges invoked the same legal language in the Fourteen Articles to support the opposite conclusion: a “relatively good marital foundation” and the existence of “reconciliation potential.” While plaintiffs also frequently referred to various types of wrongdoing stipulated in Article 32 of the 2001 Marriage Law (infidelity tantamount to unlawful cohabitation or even bigamy, gambling, domestic violence) and submitted appropriate evidence in support of their fault-based claims, judges were fixated on the breakdownism standard. As we saw in Chapter 2, legally speaking, statutory wrongdoing automatically establishes the breakdown of mutual affection: the SPC, in a 2001 judicial interpretation that carries the force of law, declared that “a divorce request should not be denied when a litigant has committed wrongdoing” (Reference JiangJiang 2009b:18). Practically speaking, however, judges overwhelmingly privileged their analysis of the quality of the marital foundation and reconciliation potential over domestic violence allegations. The Fourteen Articles, by requiring judges to analyze the reasons for marital discord and the potential for reconciliation, calls on judges to act like marriage counselors. We will see that judges went beyond making diagnostic assessments by routinely offering marital advice when they denied divorce petitions.

In the remainder of this chapter I present qualitative case examples showcasing judges’ repertoire of gaslighting strategies. I organize into seven sections the various discursive strategies deployed to sideline and neutralize domestic violence allegations.

Judges Almost Uniformly Applied the Breakdownism Standard

Ultimately, the breakdown of mutual affection is the standard that mattered most to judges. The following represents tens of thousands of court decisions in my samples containing nearly identical language: “Mutual affection is the foundation of marriage, and the statutory standard by which the People’s Court grants and denies divorces is whether or not mutual affection has indeed broken down” (Decision #939023, Xingyang Municipal People’s Court, Henan Province, January 13, 2013).Footnote 4 Some judges even proclaimed in their holdings that breakdownism is the only relevant legal test: “The court holds that whether or not marital affection has completely broken down is the sole standard by which to weigh the decision to grant or deny a divorce” (Decision #2393036, Zhuji Municipal People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, October 14, 2011).Footnote 5

Supplementary case examples set #7–1 is online at: https://decoupling-book.org/.

A key task for judges, then, was to reconcile an irreconcilable legal contradiction: the presence of domestic violence in the absence of the breakdown of mutual affection. A defendant’s lack of consent was often the only evidence judges needed to deny divorce petitions according to the breakdownism standard (Reference XuXu 2007:204). Holdings such as this were commonplace: “The defendant’s unwillingness to divorce shows that marital relations between the plaintiff and defendant have not completely broken down” (Decision #1644365, Zhongmu County People’s Court, Henan Province, August 7, 2015).Footnote 6 Judges sometimes even used procreation as evidence of mutual affection. A holding that “the couple has been married for X years and has a child” was the common basis of an adjudicated denial.

The plaintiff and defendant have lawful marital relations that should be protected by law. After marrying they had two children, which shows that they built definite mutual affection when living together. At this time the plaintiff requests a divorce, but she did not submit evidence proving that mutual affection has indeed broken down. For this reason, the court denies support of her petition.

Even in cases involving compelling allegations of domestic violence, judges frequently justified denying petitions for the sake of the children, as if prolonged exposure to violence somehow promoted “the healthy upbringing of children,” a common refrain in judges’ holdings.

Even when judges did not use the specific term “mutual affection,” such as in the following examples of adjudicated denials, they nonetheless applied the breakdownism test using a similar language.

Plaintiff Fang and Defendant Wang freely and willingly registered their marriage and had a son. Their marital foundation is relatively good. Post-marital conflict between husband and wife is minor. Their disagreements are over trivial matters. Defendant Wang pledged to correct his violent temper. Husband and wife have the potential to reconcile provided they improve their communication and show mutual understanding, forgiveness, and tolerance.

Supplementary case examples set #7–2 is online at: https://decoupling-book.org/.

When judges were hard-pressed to hold that marital affection had not broken down, they could always deny a divorce petition on the basis of political ideology and socialist morality. This was another strategy they deployed to square the legal circle.

Judges Privileged Political Ideology and Socialist Morality over the Law

On the rare occasions that judges invoked fault-based language in their holdings, it was almost always to invalidate plaintiffs’ claims of wrongdoing. Judges often avoided addressing plaintiffs’ fault-based claims altogether by couching their adjudicated denials in ideologically resonant words and terms such as “harmony,” “stability,” “civilized,” and “frivolous divorce” (also see Reference AhlAhl 2020:178). The following examples are excerpts from holdings in cases involving plaintiffs’ allegations of wrongdoing.

Family is the cell of society, and family harmony is a precondition of social harmony. Although the freedom of marriage in the Marriage Law includes the freedom of divorce, once marriage is established family obligations must be assumed. For this reason, the law does not permit frivolous divorce.

The court holds that the family is the cell of society, and that marital and family stability have a direct bearing on social stability as a whole.

In order to preserve the stability of socialist marriage and family, the court denies support of the plaintiff’s request.

The defendant does not consent to divorce and still desires to preserve the marriage, which proves that there is still reconciliation potential. For this reason, in order to protect family harmony and stability, and in consideration of the healthy upbringing of minors, the court denies support of the plaintiff’s divorce petition.

The last example illustrates not only the salience of political ideology but also judges’ tendency to use of defendants’ unwillingness to divorce as evidence that mutual affection had not broken down.

Supplementary case examples set #7–3 is online at: https://decoupling-book.org/

As we saw in Chapter 6 (Table 6.5), judges denied the majority of divorce petitions on the first attempt but granted the majority of subsequent divorce petitions. Sometimes, however, plaintiffs required three or four attempts – as we saw at the beginning of Chapter 1 – or even five attempts – as we saw with the case of Ning Shunhua in Chapter 3 – before judges finally granted their divorce petitions. Indeed, sometimes judges will deny petitions seemingly without limits. In its decision to deny a plaintiff’s fifth divorce petition, Henan’s Qingfeng County People’s Court wrote that “the number of divorce petitions filed is not a measure of whether or not mutual affection has broken down. Defendant Yao X has believed all along that marital affection is very good and that husband and wife can continue to live together. For this reason, marital affection has not reached the point that it has indeed broken down” (Decision #987756, May 16, 2013).Footnote 13

As they heeded the political call to preserve marriages, judges sometimes made moral arguments of no legal relevance. On her second divorce attempt, the plaintiff, just as she had done the first time, claimed her husband frequently “beat her black and blue” (打得青紫不断). In particular, she alleged that on May 28, 2014, her husband beat her ruthlessly (死命打), after which she called 110 for help (the equivalent of 911 in the United States) and the next day sought assistance from the All-China Women’s Federation. She went on to claim that on July 8, 2014, the defendant almost choked her to death, and that he released her throat only when she bit his hand. She submitted medical documentation as evidence. The defendant challenged the evidence by arguing that it failed to prove he caused the injury in question, and that she was the one who started it in the first place when she rubbed food in his face. Similar to the contents of the “notice of cooling-off period” cited in Chapter 3, the court’s holding in this case invoked a moralistic appeal of no legal relevance intended persuade the litigants to stay together.

There is an old saying: Each marriage is the destiny of a union in this life formed over three previous lifetimes [凡为夫妻之因, 前世三生结缘, 始配今生夫妇]. Husband and wife, affectionately face to face, inseparable lovers and friends, beautifully united, with profound conjugal love, are of two bodies and one heart. … And yet you came to court to divorce while others look on and sigh with lament! … Life is not a dress rehearsal; every day is a live broadcast. If life were like a video game that you can lose and restart from the beginning, what do you think life would become? Time that passes is never returned. Each day that goes by cannot be recovered. For this reason, you must cherish every moment. You must also treasure each other, communicate with sincerity, love each other, and jointly nourish with care this precious gift of a family.

Judges Gave More Credence to Defendants’ Denials than to Plaintiffs’ Allegations

As we saw in Chapter 2, SPC rules allow judges to apply a “preponderance of evidence” standard when adjudicating between two versions of events. In my sample of tens of thousands of divorce cases involving claims of domestic violence, however, one judge did so. In this solitary case, the litigants made typical statements. The plaintiff alleged that her husband had beaten her, covered her body in bruises, bitten her arm, and kicked her stomach when she was pregnant. In addition to petitioning for marital dissolution, she also claimed civil damages for emotional distress. As evidence, she submitted a copy of a “pledge letter” in which her husband admitted beating her as well as six photographs documenting the injuries she sustained. To support his denial of her allegations, the defendant argued that the events precipitating her calls for emergency police assistance were not domestic violence but “merely mutual acts of domestic quarreling,” and submitted police reports from two such calls in support of his version of events. Applying the “preponderance of evidence” standard (Chapter 2), the court held:

In this case, although the defendant denied carrying out domestic violence and denied causing the injuries in the photographs submitted by the plaintiff, police reports of the plaintiff’s emergency calls establish that physical conflict occurred on September 28, 2013 and that the defendant both beat the plaintiff causing a head injury and bit and injured the plaintiff’s right arm on June 16, 2014. In light of the hidden nature of domestic violence, the unwillingness of outsiders to intervene, and a desire to prevent others from finding out, these events are consistent with the informal ways domestic conflicts are handled after they are reported to the police. The court holds that the probability is relatively high that the injuries depicted in the photographs submitted by the plaintiff were caused by the defendant. Moreover, the defendant’s pledge letter shows that he beat the plaintiff once again on October 23, 2013 and admitted inflicting all kinds of suffering on the plaintiff when she was pregnant, resulting in serious physical and psychological harm.

Although the litigants’ statements were typical, the court’s ruling was atypical in several respects. First, the court granted the divorce on the first attempt, albeit perhaps in part because the defendant consented to divorce. Second, the court awarded civil damages. Wrongdoing is a precondition of civil damages, and judges rarely affirmed the occurrence of domestic violence (which would privilege faultism standards for granting divorce over their preferred breakdownism standards for denying divorce). Judges can only grant civil damages according to Article 46 of the Marriage Law if they first affirm the occurrence of one of four faults: (1) bigamy, (2) cohabitation with a third party, (3) domestic violence, and (4) maltreatment or desertion of a family member.

Rarely, however, did litigants request “compensation for emotional distress” (精神损害抚慰金, 精神损害赔偿金, and similar terms) or other types of damages despite their legal right to do so. In the full Henan sample, I found only 3,247 requests for civil damages from plaintiffs and 1,545 from defendants (4.5% and 2.1% of all 72,102 adjudications, respectively). In the full Zhejiang sample, I found only 1,003 requests from plaintiffs and 687 from defendants (1.4% and 1.0% of all 72,048 adjudications, respectively). Of all of these 6,482 claims for civil damages I was able to identify in both samples (4.5% of all 144,150 adjudications), only 294 were awarded with some amount of compensation (4.5% of all requests, and 0.2% of all adjudications). Moreover, only between one-third and one-half of plaintiffs’ requests for civil damages were associated with domestic violence allegations. Even when courts granted divorces, they were exceedingly unlikely to recognize the few claims of plaintiffs who both made allegations of domestic violence and requested civil damages: they awarded civil damages in only 5.8% and 14.9% of such cases in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively. The rarity of both claims for and awards of civil damages in my samples mirrors findings in previous research (Reference Bu, Xiaoting and LinBu, Li, and Lin 2015:13; Reference Chen, Shi and ZhangChen, Shi, and Zhang 2016; Reference DengDeng 2017:111–12; Reference LiLi 2015b; Reference LiLin, Bu, and Li 2015:125). Plaintiffs are reluctant to claim civil damages in part because they know that, owing to the divorce twofer, they will likely leave court without a divorce and face the possibility of retaliation from their abusive husbands (Reference DengDeng 2017:113).

Third, the judge in this case, by ruling that the evidence favored the plaintiff’s claims more than the defendant’s claims, chose to believe the plaintiff’s claims. From the standpoint of the law, judges are supposed to give women the benefit of the doubt in “he said, she said” scenarios. In domestic violence cases, they are supposed to relax ordinary evidentiary standards by applying the “preponderance of evidence” rule – precisely as this judge did. Judges typically ignored plaintiffs’ allegations, however, even when they were supported by evidence. Chinese courts have seemingly limitless discretion with respect both to admitting and excluding evidence and to affirming and disaffirming litigants’ claims. Judges could and did deny divorces willy-nilly regardless of the quantity and quality of evidence supporting claims of defendant wrongdoing.

One court decision in the Zhejiang sample provides an example of a widespread phenomenon of judges’ misusing or ignoring the applicable laws and SPC interpretations (including opinions and guidelines) I reviewed in Chapter 2. The plaintiff’s allegations in this case were as follows. During an argument over their daughter’s school tuition in August 2009, the defendant beat the plaintiff, causing her to suffer a dislocated atlanto-axial joint (between the first and second cervical vertebrae of the neck) and as a result to spend eight days in the hospital. On November 13, 2009, the defendant intimidated the plaintiff by threatening in text messages, among other things, to use sulfuric acid to mutilate her. On March 1, 2010, the defendant beat the plaintiff at her workplace before a crowd. To support these claims, the plaintiff submitted two photographs documenting the March 1, 2010, injury; two sets of hospital records; an incident report from the local police substation documenting the threatening text messages; a “pledge letter” dated March 3, 2010, written under the urging of the local police substation and the villagers’ committee in which the defendant promised to stop beating the plaintiff; and a statement from the village mediation committee documenting multiple mediation efforts that were precipitated by marital tensions, conducted over the previous few years, and ultimately proved unsuccessful. The defendant simply stated, “I do not consent to divorce, the plaintiff’s statements are false, and I wish to reconcile with the plaintiff.” In response to the plaintiff’s evidence, the defendant confirmed writing the pledge letter but disavowed its contents (“I wrote what the village leader told me to write”); had no objections to the police incident report and one set of hospital records; professed ignorance about the second set of hospital records; and denied causing the injury in the photographs. In its holding, the court affirmed every piece of evidence, even stating that the photographs showed bruising on the plaintiff’s right hand and that the hospital records dated March 1, 2010 established that the plaintiff’s left shoulder had been injured by a forcible blow inflicted by “another person’s fist” within one hour of the medical examination. Although the court did not exclude any of the submitted evidence, it nonetheless did not explicitly state that the documented injuries had been caused by the defendant. The court stated that the plaintiff’s evidence only proved “the occurrence of several incidents of conflict” and poor results of mediation conducted by the police substation and villagers’ committee, but failed to prove the breakdown of mutual affection, particularly in light of the defendant’s opposition to the divorce request and hope for reconciliation. Declaring that reconciliation remained possible, the court denied the plaintiff’s divorce petition (Decision #2333373, Anji County People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, April 16, 2010).Footnote 16

Another woman alleged that her husband frequently raped her. She told the court that for several years she had slept in a separate room, and that, under his mother’s urging, her husband had on many occasions broken in and forced himself on her while his mother watched. She recounted another time when her mother-in-law and sister-in-law attacked and choked her. She testified that on one morning, her husband and mother-in-law broke into her room, at which point he held her down on the bed, forcibly removed her clothes, beat her, and “committed a brutal act” that left bruises on her body and for which there was forensic documentation. In support of her allegations, she submitted a copy of a “pledge letter” written by the defendant proving that he beat her. In his defense, her husband denied all her allegations, arguing that she fabricated them in an effort to get away with her unspecified “betrayal.” Without pursuing additional evidence, the court ruled as follows:

Husband and wife should be mutually loyal and respectful. Although plaintiff and defendant were not acquainted for long before marrying, no fundamental conflicts have arisen after marrying. Moreover, they have already given birth to a son and a daughter, and have retroactively registered their marriage. In the past two years, the defendant has been unable to deal correctly with marital affection and family conflict. Both sides have fought over trifles, bringing harm to their marital affection. Both sides should diligently reflect on and learn from their experiences, and, taking the interests of family harmony and the physical and psychological health of their children as the starting point, forgive, accommodate, and respect each other, and together build a harmonious, happy family. In the course of the trial, the plaintiff failed to submit evidence that mutual affection has broken down, the defendant did not consent to divorce, and the defendant expressed his hope to live happily with the plaintiff. The court is therefore unable to affirm the breakdown of mutual affection. In order to protect the stability of marriage and the physical and psychological wellbeing of children, the court, in accordance with Article 32 of the Marriage Law, hereby denies to grant a divorce between plaintiff Luo X and defendant Ding X.

A defendant was likely to deny a plaintiff’s claim that he caused her injury, and the court was likely to side with him by ruling that the plaintiff’s evidence proved only that an injury occurred but not who caused it. When plaintiffs supported their allegations of domestic violence with photographic evidence of injuries, courts often supported defendants’ objections that the submitted evidence failed to establish the cause of an injury. As a typical example, a plaintiff described an incident in which the defendant battered her to the point that “my body was covered in blood and sustained soft tissue injuries in several places.” She supported her claim with a diagnostic report from a local hospital, a letter from the local police substation, and a photograph. To support his counterclaim that the plaintiff caused her own injuries by hitting herself, the defendant submitted a CD (光盘), the contents of which were undisclosed. The court held that

although marital affection has been harmed by conflicts, anger, and physical and verbal fighting over trifling matters, the breakdown of mutual affection has not reached the level stipulated by the Marriage Law. Furthermore, because the defendant is unwilling to divorce and strongly desires reconciliation, the plaintiff and defendant should have an opportunity to reconcile. The court therefore denies the plaintiff’s divorce petition.

Supplementary case examples set #7–4 is online at: https://decoupling-book.org/.

Defendants often counterclaimed that the alleged injuries were self-inflicted (Reference FincherFincher 2014:152). In the following example, the court affirmed that an injury had in fact occurred, but, after the defendant denied causing it, failed to affirm the defendant’s responsibility for the injury, and ultimately denied the plaintiff’s divorce petition. It illustrates judges’ tendency to support defendants’ denials of domestic violence allegations.

In support of her claims, the plaintiff provided five photographs showing injuries to prove the defendant’s frequent violence. Defendant’s statement: Mutual affection with the plaintiff is very good and I do not consent to divorce. Only two of the five photographs provided by the plaintiff depict the plaintiff, and the other three are of someone else. Furthermore, I did not cause the plaintiff’s injuries. Rather, she caused them herself by falling down the stairs.

Supplementary case examples set #7–5 is online at: https://decoupling-book.org/.

On her third attempt to divorce in court, a female plaintiff testified that her husband’s violence intensified after she withdrew her first divorce petition following a court-mediated reconciliation. As she explained, she had given him an opportunity to fulfill his promise to stop beating her for six months, at which point she would be eligible to file a new divorce petition. She described how he choked her; how he dragged her out of bed by her feet and down the stairs; how he attacked her with a knife; how she called the police after he smashed a new bed she bought; and how, in front of the police, he declared his intention to murder her entire family. To support her claims, she submitted six photographs. He objected to all of them for different reasons. He said one photograph depicted an injury that was the result not of his beating her but rather of getting struck by the bed when – as he admitted – he flipped it over. Because it found that the photographs “cannot prove the defendant carried out domestic violence against the plaintiff,” the court excluded them from evidence. As Chinese courts so often did in similar cases, the court denied the plaintiff’s petition on the grounds that the couple’s relatively long acquaintanceship before marriage and their relatively solid marital foundation made reconciliation still possible, provided they put family and child first, strengthened understanding and trust, and paid attention to managing and controlling their emotions. In this case, the total duration of time from her first divorce attempt to the actual divorce was two-and-a-half years (Decision #4521359, Hangzhou Municipal Yuhang District People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, June 17, 2016).Footnote 20

Another plaintiff, like so many subjected to the divorce twofer, testified that marital affection did not improve after the court denied her first divorce petition. She specifically alleged that her husband had beaten her and that she had reported him to the police on more than one occasion in the time since the previous trial. She had filed her first divorce petition the year before, and claimed to have suffered a broken rib during one of her husband’s many instances of abuse. To support her claims, she submitted a copy of a police report. The defendant counterclaimed that her injury was not the result of his beating but rather the result of his pulling her back to safety when she rushed up to the fourth floor to jump off the building. The court denied the plaintiff’s petition for divorce after holding that the litigants had built significant marital affection through their over ten years of marriage and birth of a son, and after insisting that they could reconcile – if only they corrected their shortcomings, empathized with and trusted each other, and gave greater consideration to family and child. In this case, the total duration of time from her first divorce attempt to the actual divorce was over one-and-a-half years (Decision #4643900, Yongkang Municipal People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, August 8, 2016).Footnote 21

Judges Denied the Validity of Plaintiffs’ Evidence on Behalf of Absentee Defendants

Even when defendants did not deny plaintiffs’ allegations of domestic violence, judges sometimes did so on their behalf. In both of the following examples, the defendant failed to participate in trial proceedings. Luckily for them, the judges acted – in a manner of speaking – as their advocates.

[The defendant] often beats me without provocation. Domestic violence is a constant. In recent years the defendant’s beatings have intensified, and the defendant has tried to desert me by forcing me out of the home. When drunk, the defendant becomes wild and curses and beats me, and has even wielded a knife to kill me. At around 7 pm on the lunar calendar’s 20th day of the 12th month of 2009 … the defendant went after me with a knife to my parents’ home and tried to hack me to death. Thankfully someone pulled me away and I escaped injury. At around 11 pm on August 8, 2010 the defendant refused my offer of ¥20,000 in exchange for a divorce and held a knife to my neck. The blade cut my skin leaving a wound 2 cm in length. For this reason, living together is impossible, and mutual affection has completely broken down. … The plaintiff submitted the following pieces of evidence: … (4) photographs proving the fact of the injury caused by the defendant’s attempt to kill the plaintiff. … The defendant made no statement of defense and submitted no evidence. … The court holds that … the plaintiff’s fourth item of evidence shows only that the plaintiff was injured but cannot prove that the defendant caused the injury, and the court therefore considers it inadmissible. … Although in recent years trifles of life have caused some conflict and impacted marital affection, mutual affection has not broken down. Furthermore, the plaintiff failed to submit evidence proving that marital affection has indeed broken down.

The next example illustrates how judges even denied the validity of evidence supporting plaintiffs’ claims of physical separation. It also foreshadows my discussion in Chapter 9 of the relationship between domestic violence and labor migration.

In the beginning of 2011, the defendant suspected I was carrying on with another man. Holding a knife, he threatened and beat me. I had no choice but to leave home and go to [the city of] Xinxiang to work. After a while I missed my children and returned to visit them. At that time the defendant beat me again. He also prohibited our children from calling me mother. Later on someone introduced me to a job in [the provincial capital of] Zhengzhou. The defendant’s actions have caused tremendous physical and psychological harm to me. … The defendant did not make a statement. In support of her claims, the plaintiff submitted the following pieces of evidence: … (2) a housing rental lease signed by the plaintiff and Yin X on May 30, 2011 and an affidavit signed by Yin X on April 20, 2013, both for the purpose of proving that marital relations have broken down according to the defendant and plaintiff’s continuous physical separation since May 30, 2011, which meets the two-year requirement. … The defendant submitted no evidence. … From its review of the evidence, the court finds that … the plaintiff’s second set of evidence proves only that a tenant-landlord relationship exists between the plaintiff and Yin X, but proves neither that the plaintiff and defendant are living apart nor that mutual affection has broken down. Furthermore, Yin X did not testify in court. These pieces of evidence are therefore inadmissible. … The court holds that if both sides let bygones be bygones and mutually respect one another, they can certainly form a harmonious and civilized family. For this reason, the court denies support of the plaintiff’s petition.

Supplementary case examples set #7–6 is online at: https://decoupling-book.org/.

Judges Trivialized Violence

Trivializing abuse as “failing to rise to the level of domestic violence” allowed judges to reconcile invoking breakdownism to deny a divorce request after affirming the occurrence of physical abuse. Remarkably, they did so even when defendants openly admitted to beating their wives. In one case, the female plaintiff provided photographs and medical records of seven days of inpatient hospital treatment for an injury sustained by the defendant’s domestic violence. The defendant admitted beating her and causing the injury, but after adding that “the incident happened for a reason,” he said he did not consent to the divorce. The court concluded that “although in the course of living together husband and wife have become angry about household chores and other minor life matters, and beatings have occurred as a result, they have been rare and do not constitute domestic violence, and therefore do not prove that mutual affection has indeed broken down” (Decision #952495, Nanzhao County People’s Court, Henan Province, February 28, 2013).Footnote 24

In her statement to the court, a plaintiff claimed that “the defendant on many occasions physically injured me. For the sake of my son, I repeatedly tolerated his abuse, but endured serious domestic violence as a consequence.” Although the defendant admitted beating and cursing the plaintiff, he denied committing domestic violence. Moreover, he said he beat her because she played too much mahjong and was unfaithful. In its holding, the court wrote:

Although the defendant occasionally beat and cursed the plaintiff, there is no evidence that his acts of beating and berating the plaintiff were frequent and persistent or that they caused serious consequences, and they therefore do not constitute domestic violence. Furthermore, the plaintiff failed to provide evidence of other statutory conditions of the breakdown of mutual affection. The court therefore denies support of the plaintiff’s petition to divorce the defendant.

The foregoing case illustrates judges’ discretionary application of an SPC judicial interpretation that includes “frequency and persistence” in its definition of domestic violence (Chapter 2). Judges even denied divorce petitions after affirming the occurrence of domestic battery. In one case, the court denied the plaintiff’s second divorce petition even though it affirmed her claim that her husband injured her head when he beat her in 2010, three years after it denied her first divorce petition. In light of the defendant’s continued unwillingness to divorce, his repeated pleas for forgiveness, and “considering that marital conflict caused by everyday domestic issues is unavoidable, the court is unable to establish the existence of the odious habit of recurrent domestic violence” (Decision #824784, Zhengzhou Municipal Zhongyuan District People’s Court, Henan Province, July 11, 2012).Footnote 26

Another plaintiff recounted the following history of injuries. In 2008, she was hospitalized after the defendant caused a concussion and chest hemorrhaging. In 2012, she was hospitalized again after the defendant cut her with the glass lining of a hot water thermos and smashed a beer bottle over her head, causing a cerebral hematoma. In 2013, she was hospitalized for 13 days with a broken nose, a fractured eye socket, an ear contusion, and head and chest wounds. To support her allegations, she submitted as evidence police and hospital documentation. In his defense, the defendant stated: “I do not consent to divorce, marital relations are good. Both sides occasionally argue and fight, but afterwards we’re as good as new.” The court, in an epic understatement, held: “In recent years, some conflict has emerged over family trifles. Last year the defendant was on the extreme side of contentious, but mutual affection has not declined to the level of complete breakdown” (Decision #2859679, Longquan Municipal People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, March 5, 2014).Footnote 27

In hundreds of decisions in my samples, courts trivialized claims of physical abuse, often supported by medical and police documentation, by reducing it to “unavoidable friction” (variations of 有些摩擦在所难免). My samples are replete with examples of courts’ normalization of abuse. In one case, the plaintiff claimed that the defendant ruptured both of her eardrums and threatened to stab her and her whole family to death, and that she reported him to the police, who “took him away.” In his statement, the defendant simply said, “I do not consent to divorce, affection between me and the plaintiff has not declined to the point of breaking down.” In its holding, the court stated that “squabbling over family trifles is unavoidable in marriage” (Decision #1194815, Miyang County People’s Court, Henan Province, June 23, 2014).Footnote 28

Similar to judges elsewhere in the world (Reference JeffriesJeffries 2016:8), Chinese judges reframed and redefined domestic violence as mere “pushing and shoving” and as mutual fighting (Reference FincherFincher 2014:145) in order to undermine plaintiffs’ efforts to establish fault-based grounds for the breakdown of mutual affection.

Plaintiff’s statement: … moreover the defendant has committed severe domestic violence, which I have reported to the police numerous times. However, the defendant has not changed one bit. Despite writing countless pledge letters, the defendant has never respected any of the promises they contain. At the end of 2012, I filed for divorce in court, and the case was concluded by mediated reconciliation. However, the defendant failed to atone for past mistakes. On the contrary, domestic violence against me intensified. … In September 2015 I filed for divorce again in court, and for various reasons the court denied my petition. But the current situation has not improved the least bit. The defendant carries out even more domestic violence against me. For this reason, I am filing for divorce. … The plaintiff submitted the following supporting evidence: … (2) 18 text messages proving that the defendant committed domestic violence; (3) one pledge letter proving that mutual affection has broken down and that the defendant has committed domestic violence; (4) one court mediation decision and one court adjudication decision proving that the plaintiff had already filed two divorce petitions in court and that this is the third time filing for divorce, which also proves that mutual affection has broken down; … (6) one personal safety protection order application proving that I am a domestic violence victim; (7) 20 WeChat messages proving that the defendant’s threatening behavior constitutes domestic violence; and (8) police visit receipts and appraisal notices proving the defendant’s actions against me and my family constitute domestic violence. Defendant’s statement: … I object to the plaintiff’s allegations of domestic violence. I believe that knocking and bumping [磕磕碰碰] into each other is a normal part of marital life. … The court holds that whether mutual affection has broken down is the basis of deciding whether to grant a divorce. Quarrels over family trifles are a normal phenomenon in marital life and difficult to avoid. The plaintiff filed for divorce once again after the court denied the plaintiff’s previous petition on November 11, 2015, but the plaintiff has still failed to provide evidence sufficient to prove that mutual affection has broken down, that the defendant committed domestic violence, gambled, used drugs, or has another odious habit, or that the plaintiff and defendant have been physically separated for at least two years.

Supplementary case examples set #7–7 is online at: https://decoupling-book.org/.

Courts often affirmed plaintiffs’ evidence of domestic violence while simultaneously denying the breakdown of mutual affection. In her legal complaint, a plaintiff described her husband as “petty” (小心眼) and then claimed he frequently read her cell phone messages and forbade her from interacting with other men. According to the plaintiff’s statement, her loss of personal freedom was the reason for their many fights, including one after which she was hospitalized with a broken nose and bruised right eye. On the basis of medical documentation submitted by the plaintiff and witness testimony, the court affirmed her claim of domestic violence as factual. The defendant failed to appear in court or to submit a written defense statement. In its ruling to deny the plaintiff’s divorce petition, the court wrote:

The plaintiff believes that... the defendant committed domestic violence against the plaintiff, causing the complete breakdown of mutual affection. Although the court holds as factual the defendant’s injury of the plaintiff on April 27, 2010, it also holds that it was an occasional act of violence caused by trifles of life, does not constitute an act of recurrent violence, and therefore does not fall within the scope of domestic violence as stipulated by the Marriage Law. (Decision #2348792, Sanmen County People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, June 17, 2010)Footnote 30

Judges also held that marital affection and reconciliation potential persisted owing to abusive defendants’ love for their wives and commitment to rectifying their errors. Judges discursively transformed what plaintiffs understood as intolerable and unlawful abuse constituting grounds for divorce into innocent misunderstandings and mistakes on the part of caring husbands, and in so doing gaslighted plaintiffs by calling into question their sense of reality (Reference SweetSweet 2019). In response to a plaintiff’s request for a divorce on the grounds of “the defendant’s ceaseless physical abuse and domestic violence,” the defendant responded by stating, “I was not calm enough, truly did beat her, and regret what I did; no matter what, it is wrong to hit people, and I admit my mistake.” In its holding, the court declared: “The defendant is sincere about repenting, mending his ways, and putting an absolute end to heated behavior. … The plaintiff’s grounds for divorce do not meet the statutory requirement stipulated by the Marriage Law that mutual affection has broken down, and the court therefore denies support of the plaintiff’s petition” (Decision #1575160, Luohe Municipal Shaoling District People’s Court, Henan Province, July 28, 2015).Footnote 31

Supplementary case examples set #7–8 is online at: https://decoupling-book.org/.

Judges Ignored Police Warnings

With respect to legal responses to domestic violence, Zhejiang’s city of Wenzhou was an early bird in a couple of respects. First, according to one report, in 2006, it issued China’s first anti-domestic violence government order, the Provisions of the Municipality of Wenzhou on Preventing and Combatting Domestic Violence. Second, at the end of 2013 it created a domestic violence warning system governed by the Measures of the Municipality of Wenzhou for the Implementation of a Domestic Violence Warning System (Reference ZhouZhou 2013).Footnote 32 Jiangsu had already taken the lead on domestic violence warning systems earlier in the same year (Reference Tan and TanTan 2016). Zhejiang’s cities of Jiaxing and Lin’an followed suit within a few years (https://perma.cc/6XTQ-AY8A; https://perma.cc/XTV6-AXP7). Under these systems, police authorities issue written warnings (家庭暴力告诫书) for “minor incidents, such as face slapping, that do not constitute criminal battery.” These written warnings were also intended to serve as evidence in divorce trials (Reference ZhouZhou 2013). Indeed, they were incorporated into the 2015 Anti-Domestic Violence Law, which stipulates that judges can use them to affirm the occurrence of domestic violence (Article 20). In the first two years of this system, Wenzhou issued 471 domestic violence warnings (Reference LiuJ. Liu 2016). In 2017, these systems went province-wide with the Measures of the Province of Zhejiang for the Implementation of a Domestic Violence Warning System. Article 13 in both versions is clear: “In divorce trials involving domestic violence, people’s courts may use domestic violence warnings as evidence to affirm domestic violence as a factual occurrence.”

In practice, however, very few domestic violence warnings ended up as evidence in trials – either civil or criminal. Even when divorce-seekers did submit domestic violence warnings in support of their fault-based claims, judges still found ways to deny their divorce petitions. Forced to accept occurrences of domestic violence as facts, judges would (mis)characterize them as insufficiently serious or too “minor” to satisfy statutory faultism standards.

One plaintiff submitted a domestic violence warning documenting a head injury with red swelling caused by the defendant. The husband challenged the evidence by stating, “it was because of a dispute that occurred when the plaintiff insulted me.” Despite affirming the admissibility of the evidence, the court denied the plaintiff’s petition for divorce under the pretext of insufficient evidence of the breakdown of mutual affection. In its holding, the court wrote: “Although the defendant carried out a minor act of domestic violence, he did not commit another such act after the Public Security Bureau issued its warning” (Decision #3936527, Wenzhou Municipal Longwan District People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, November 17, 2015).Footnote 33

Another judge, before denying the plaintiff’s petition for divorce, held that the evidence was inadmissible for the following reason:

The domestic violence warning simply recorded a fight between the two sides that led to an injury to the plaintiff’s scalp, which, according to the plaintiff’s testimony, required only three stitches. Moreover, because the plaintiff was unable to provide additional corroborating evidence, the allegations could not be affirmed as factual. … The plaintiff claimed that the defendant committed a serious instance of domestic violence but failed to submit evidence proving it.

In each of these cases, the presiding judge recast what should have been a legally unambiguous occurrence of domestic violence as, respectively, “a minor act” and “a fight between the two sides” falling short of “a serious incident of domestic violence.” By redefining domestic violence as relatively harmless and/or mutual fighting, judges denied divorces to plaintiffs legally deserving of divorce.

One court even went so far as to hold that a domestic violence warning “could not fully and effectively prove the occurrence of domestic violence as a factual matter,” and that it therefore “did not affirm a link between this piece of evidence and the plaintiff’s claim of domestic violence.” For these reasons, the court denied the plaintiff’s divorce petition (Decision #4554804, Tiantai County People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, June 17, 2016).Footnote 35

On June 19, 2016, less than a month after a plaintiff withdrew her divorce petition on May 23, 2016, her husband received a domestic violence warning. She filed for divorce once again two days later, on June 21, 2016. Recall that the Civil Procedure Law provides for an exception to the six-month statutory waiting period on the basis of “new developments” or “new reasons” (Chapter 3). Although the plaintiff claimed that the incident precipitating the domestic violence warning constituted a “new development,” the court disagreed, holding that domestic fights had long been a fixture of their marriage, and refused to hear the case. Whereas domestic violence claims are usually an inconvenient obstacle courts ignore or clear out of the way in order to deny divorce petitions, in this case the court used recurrent violence to its advantage as an expedient means of making the case go away for at least a few more months (Decision #4591750, Chun’an County People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, July 21, 2016).Footnote 36

Supplementary case examples set #7–9 is online at: https://decoupling-book.org/.

As we have seen, defendants’ unwillingness to divorce provides the ideal pretext for courts to deny the breakdown of mutual affection. Instead of granting divorce petitions on the grounds of fault-based evidence of domestic violence, judges routinely swept aside domestic violence allegations when defendants were unwilling to divorce or affirmatively expressed their desire to reconcile. By privileging breakdownism over faultism, judges took abusive defendants’ contrition and wish to stay together as evidence of reconciliation potential and therefore as grounds for denying divorce petitions.

Judges Misused Pledge Letters

Abusers, sometimes at the behest of authorities, made written apologies for beating their spouses and written promises to stop their wrongdoing. They often broke those promises. A court decision granting a woman’s application for a personal protection order against her husband documents an incident in which, under the belief that she was at her older sister’s home, he attacked her brother-in-law with a knife only six days after promising in a pledge letter never to beat her again (Decision #4545264, Qingtian County People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, June 1, 2016).Footnote 37

In divorce trials, judges’ regularly misused defendants’ promises and apologies. Judges even turned such evidence against plaintiffs, in violation of the 2008 Guidelines. When plaintiffs submitted pledge letters as evidence of the breakdown of mutual affection, judges sometimes treated them as evidence of the existence of mutual affection. Hundreds of decisions in my samples contain court holdings with language such as: “After getting married, the defendant physically abused the plaintiff. However, the defendant issued a pledge letter, which the plaintiff accepted, expressing the defendant’s enthusiastic commitment to drug rehabilitation. This shows the defendant’s recognition of his mistakes and desire to restore this marriage” (Decision #2874358, Anji County People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, May 6, 2014).Footnote 38 Although the 2008 Guidelines clearly stipulate that courts should accept pledge letters containing relevant content as evidence of domestic violence, they often failed to do so (e.g., Decision #4865420, Lanxi Municipal People’s Court, Zhejiang Province, October 24, 2016).Footnote 39

My final qualitative example in this chapter brings together a number of themes. First, despite an abundance of evidence documenting the defendant’s history of domestic violence, including a personal protection order, a public security administrative punishment decision, a pledge letter, and the defendant’s self-incriminating testimony, the judge ruled against the plaintiff. Second, the court misused the defendant’s pledge letter. Rather than using it for the plaintiff’s intended purpose of proving domestic violence and establishing grounds for divorce, the court used it as evidence of the defendant’s contrition, the possibility of marital reconciliation, and the absence of the breakdown of mutual affection. Third, the court appeared to apply the criteria of frequent and persistent to the definition of domestic violence in its holding to disaffirm the plaintiff’s allegations.

After the plaintiff initially filed for divorce in 2005, the court’s attempt to achieve mediated reconciliation succeeded when she withdrew her petition in order to give him a second chance. She filed again in December 2015. In March 2016, the court once again attempted to mediate, this time unsuccessfully. The court then approved the plaintiff’s request for a personal protection order. In response to the plaintiff’s harrowing and thoroughly documented testimony of chronic abuse causing “serious injuries,” “tremendous anxiety and psychological darkness,” and “psychological trauma,” the defendant admitted to his violence. “I admit smashing the window on the front door of the plaintiff’s family home, but I did it because I couldn’t get in. On November 16, 2015, at about 6:00 pm I slapped the plaintiff four times.” Regarding the medical documentation and photos the plaintiff submitted, the defendant stated, “I do not object to their authenticity. The photos are from when I hit her on the evening of November 22, 2015. The situation as described is factual. However, I did not beat her more than once. Only multiple beatings qualify as domestic violence.” The defendant added,

I only hit the plaintiff once on November 22, 2015, because she pulled a disappearing act, and even transferred her cell phone number. I told her that since she came home we should try to get along. But she refused to talk to me. All she said was that she had already filed for divorce, and that if I had any questions I should ask her lawyer. I asked her eight times if she was sure she wanted to do this. When she said she was sure, I hit her. This is the best way to deal with her.

In its holding, the court even affirmed that

the defendant slapped the plaintiff five times and punched her head once. The plaintiff reported the incident to the police. On November 23 the plaintiff admitted herself to the Hangzhou X Hospital for treatment. The hospital diagnosed an internal head injury and multiple external head contusions. … On January 19, 2016, the Yuhang District Branch of the Hangzhou Municipal Public Security Bureau issued an administrative punishment decision to the defendant stating that … the defendant had beaten the plaintiff with an open hand and closed fist, causing a minor injury to the right side of the plaintiff’s face.

And yet the court denied her second-attempt petition. Judges appeared to be willing to affirm the occurrence of domestic battery, which did not legally imply the breakdown of mutual affection, while being careful not to affirm the occurrence of domestic violence, which would have legally implied the breakdown of mutual affection.

Although the plaintiff believes the defendant repeatedly beat her and her family members, the evidence she submitted as well as the evidence the court collected on her behalf only proves that the defendant beat her on November 22, 2015. Regarding the alleged incidents of January 19, February 5, and February 14, 2016, there are corresponding police reports and notes. Because the police did not resolve these incidents, the evidence only proves that the plaintiff and her parents, owing to altercations with the defendant, repeatedly sought police help, but not that the defendant repeatedly beat and abused them. Because the evidence at hand does not prove that marital affection has indeed broken down, there is insufficient evidence to support the plaintiff’s petition, and the court denies support of it. The defendant stated that the reason he beat the plaintiff on November 22, 2015 was because he wanted to talk things over with the plaintiff. However, the plaintiff had already filed for divorce and did not want to talk things over. Even if the defendant beat the plaintiff because he did not want to divorce, the use of violent means to save a marriage is not rational, appropriate, or lawful. On the contrary, it is detrimental to the improvement of marital affection. In his pledge letter, the defendant addressed this by promising never again to beat the plaintiff, and that he would work hard and take care of his family. From this day forward the defendant should avoid the occurrence of events like these, control his feelings, and show greater care and concern for the plaintiff and her family. If the plaintiff and defendant strengthen understanding and trust, are more considerate and tolerant of each other, put the interests of their family and children first, their marriage can still be reconciled.

Supplementary case examples set #7–10 is online at: https://decoupling-book.org/.

To judges, pledge letters were simply one more tool to support the pretense that reconciliation was possible, and were thus a convenient pretext for denying divorce petitions.

Summary and Conclusions

In this chapter, I have let plaintiffs and judges do most of the talking. I provided qualitative examples illustrating judges’ highly discretionary application of China’s legal standards for divorce. They reveal judges’ seemingly boundless determination to deny divorce petitions, regardless of the facts presented to them. According to China’s own laws and judicial interpretations, judges had a solid legal basis for granting the plaintiff’s divorce request in most if not all of the case examples I presented. In each case, they could have granted the divorce according to China’s faultism standards by affirming the plaintiff’s evidence of domestic abuse or according to China’s breakdownism standards by affirming the plaintiff’s claim that mutual affection had indeed broken down. In the context of domestic violence, these competing standards overlap insofar as establishing fault automatically establishes the breakdown of mutual affection. According to China’s Law on Judges, their formal professional duties and responsibilities include upholding the law and protecting the due process rights of litigants. Judges, however, are also tasked with protecting state interests (Article 10, Item 4 in tReference Hehe 2019 version). Judges’ routine denial of divorce petitions reflects their greater loyalty to prevailing political priorities such as marital preservation and social stability – and their responsiveness to institutional incentives intended to maintain this loyalty – than to the legal needs of vulnerable women. Judges are also required to maintain neutrality vis-à-vis litigants (Reference ZhuZhu 2016:223). As we have seen, however, they tended to support husbands’ denials of domestic violence allegations despite ironclad evidence and despite sources of law calling on them to give abuse victims the benefit of the doubt in cases with inconclusive evidence.

This chapter has shown how judges constructed an alternate reality in which domestic violence was merely run-of-the-mill bickering common to healthy marriages. By ignoring, downplaying, and turning on its head evidence of domestic violence, judges’ rhetorical strategies bear the quintessential hallmarks of gaslighting (Reference SweetSweet 2019). Judges discursively transformed domestic violence into ordinary tensions that can be overcome with a modicum of determination on the part of both husband and wife. In so doing, judges represented domestic violence victims as irrational, hotheaded, and overly emotional, blind to their loving husbands’ hopes for a future together; as irresponsible mothers dead set on depriving their children of the intact families necessary for their healthy upbringing; as obstacles to marital reconciliation; and thus as unpatriotic for failing to do their part to strengthen the nation by strengthening family relations.

In this chapter, I have zoomed in on selected case examples illuminating the role of domestic violence (or more precisely, the lack thereof) on judges’ holdings and verdicts. In the next chapter, I will zoom out to a view of all the first-attempt divorce adjudications in my samples.