Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder which is characterised by abdominal pain and changes in bowel habits especially in defaecation in the absence of any organic aetiologies(Reference Esmaillzadeh, Keshteli and Hajishafiee1). IBS with constipation, IBS with diarrhoea, mixed IBS and un-subtyped IBS are four divisions of the disorder based on defaecation pattern(Reference Roohafza, Bidaki and Hasanzadeh-Keshteli2). Although the exact mechanism has not yet been known, genetic problems, psychological factors, gut hypersensitivity, enteric nervous system dysregulation, neurotransmitter imbalance, previous GI infection and low-grade mucosal inflammation are the some suggested possibilities(Reference Jahangiri, Jazi and Keshteli3,Reference Guo, Zhuang and Kuang4) .

IBS is more common in females rather than males, and the age of onset is often before 50 years(Reference Khademolhosseini, Mehrabani and Nejabat5). The prevalence of this disease is different in various regions due to several diagnostic criteria or study design and ranged from 1·1 to 22 % worldwide(Reference Sorouri, Pourhoseingholi and Vahedi6–Reference Rey and Talley8). In Iran, the reported prevalence differed from as low as 1·1 % to as high as 25 %(Reference Jahangiri, Jazi and Keshteli3). This syndrome can severely impair patients’ quality of life and can cause a great burden on the patient and on healthcare resources. Total cost for people seeking IBS treatment in the USA was annually between $US 1·7 and $US 10 billion(Reference Shaheen, Hansen and Morgan9,Reference Sandler, Everhart and Donowitz10) . Economic burden caused by IBS in Iranian population was estimated to be $US 2·8 million/year(Reference Roshandel, Rezailashkajani and Shafaee11).

Multiple studies investigating different factors involved in the exacerbation or improvement of IBS symptoms have been performed. For example, diet in low amount of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols had been shown to be useful in alleviating symptoms(Reference Cozma-Petruţ, Loghin and Miere12). On the other hand, physical inactivity and insufficient sleep time were reported to play roles in symptom aggravation(Reference Sadeghian, Sadeghi and Keshteli13–Reference Baniasadi, Dehesh and Mohebbi15). Eating pattern is one of the most effective parts of dietary behaviours. Several previous investigations have reported the linkage between IBS and dietary habits such as rapid food intake, intra-meal fluid consumption and regularity/irregularity of eating(Reference Chirila, Petrariu and Ciortescu16–Reference Miwa18).

Meal frequency is one of the dietary habits that less investigated its relation with functional GI disorders(Reference Vakhshoori, Keshteli and Saneei19). Chirila et al.(Reference Chirila, Petrariu and Ciortescu16) have investigated a random sample of 193 Romanian subjects and reported that IBS patients had less meals and snacks than the control group, but this association was not statistically significant. Omagari et al.(Reference Omagari, Murayama and Tanaka20) found that among 245 young Japanese women, IBS patients in comparison with healthy individuals skipped their breakfast more often, but this finding was also insignificant. Inadequate sample size and controversial results were some limitations of previous investigations. Also, cultural differences among different populations and diversity in eating behaviours in different countries make us unable to generalise the results of previous investigations to other communities. In the current study, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between meal and snack frequency with IBS symptoms and its subtypes among a large group of Iranian adults.

Methods and materials

Participants

This cross-sectional study was done in the context of Study on the Epidemiology of Psychological, Alimentary Health and Nutrition(Reference Adibi, Keshteli and Esmaillzadeh21). The main aim of Study on the Epidemiology of Psychological, Alimentary Health and Nutrition was investigating lifestyle factors with functional GI disorders among general adult population in Isfahan province, Iran. Briefly, the study population consisted of a medical university non-academic staff, including service staff, employees and managers. The socio-economic status of the study population was representative of general Iranian population. As shown in Fig. 1, this project had two phases. In the first phase, self-administered questionnaire on lifestyle, demographic and anthropometric factors was sent to 10 087 subjects, and 8691 of them returned the completed questionnaires. In the second phase, 6236 participants filled questions about their GI profiles. The response rate in these two phases was 86·1 and 61·8 %, respectively. After merging the information of two phases, the complete information of 4669 subjects was available for the current analysis. Data of 1567 individuals could not be used in the analysis, because of incompleteness of questionnaires or identification code in phase 1 or 2 or having missing data in our pre-defined variables.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of study population

Assessment of meal frequency

For evaluation of meal frequency, participants were asked to report the numbers of their main meals (one, two or three) and snacks (none, 1–2, 3–5 or >5) consumed per day. Data of total meal and snack frequency were gathered by adding up the total number of main meals and snacks (<3, 3–5, 6–7 or ≥8 per day).

Assessment of irritable bowel syndrome

A modified Persian version of Rome Ш criteria was used to assess IBS symptoms(Reference Sorouri, Pourhoseingholi and Vahedi6). Due to the inability of participants to distinguish between measurement scaling of original questionnaire (never, <1 d a month, 1 d a month, 2–3 d a month, 1 d a week, more than 1 d a week and every day), a four-item rating scale was introduced (never or rarely, sometimes, often and always). In addition, 6 months’ duration of symptoms was substituted with a period of 3 months(Reference Sorouri, Pourhoseingholi and Vahedi6,Reference Adibi, Keshteli and Esmaillzadeh21) . IBS was assessed as having abdominal discomfort or pain at least sometimes in the last 3 months prior to the initiation of study along with at least two of the following symptoms: improvement with defaecation and changing in stool form or frequency. Constipation-predominant IBS was defined as having IBS with hard stools and lack of having any watery ones, at least sometimes. Diarrhoea-predominant IBS was defined as having IBS with watery stools at least sometimes and lack of any hard ones. Mixed IBS was defined as having IBS with both of watery and hard stools periodically. Un-subtyped IBS was defined as having IBS with lack of hard or lumpy, loose, mushy or watery stools.

Assessment of other variables

A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect information about age, sex, education level, marital status, smoking and diabetes mellitus. Data of weight (kg) and height (cm) were collected through a self-reported questionnaire. BMI was measured by dividing of weight in kg by height in square of metre (kg/m2). A validation study in a pilot study on 200 participants from the same population was done and showed that self-reported values of anthropometric measures provide reasonable data of these indices. The correlation coefficient for weight, height and computed BMI from self-reported values and the one from measured values was 0·95 (P < 0·001), 0·83 (P < 0·001) and 0·70 (P < 0·001), respectively(Reference Aminianfar, Saneei and Nouri22). Participants were also asked to report the status of consuming dietary supplements (including the intake of Fe, Ca, vitamins and other dietary supplements) (yes/no), oral contraceptives pill (yes/no) and presence/absence of colitis. GI symptoms including abdominal pain, bloating, belching or diarrhoea after milk consumption were considered as lactose intolerance. Moreover, dental status was determined through a question ‘how many teeth have you lost’, and answer choices were the following: fully dentate, lost 1–5 teeth or more than five teeth. Data of tea, chocolate and coffee consumption were also collected through a validated 106-item FFQ(Reference Keshteli, Esmaillzadeh and Rajaie23). With regard to tea consumption, subjects could select one of these options: never or <1 cup/month, 1–3 cups/month, 1–3 cups/week, 4–6 cups/week, 1 cup/d, 2–4 cups/d, 5–7 cups/d, 8–11 cups/d or at least 12 cups/d.

For determining physical activity levels, General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire was utilised. Individuals with at least 1 h/week of physical activity were categorised as the active group, and the other ones were considered as the inactive ones. Meal regularity was distinguished through choosing one answer from the four-item scale (never, occasionally, often and always). For efficacy of food chewing, participants were asked to answer the question of how thoroughly do you chew food, and the possible answers were ‘not very well, well or very well’. Participants were asked about the speed of their eating with this question: ‘how much time do you spend eating lunch or dinner?’, and the answer options were never eat lunch/dinner, <10, 10–20 and more than 20 min. Breakfast consumption information was obtained through a two-item scale (<5 and ≥5 times/week). Individuals were also asked about intra-meal fluid intake by the question of ‘how often do you drink liquids before, with or after meals?’, and the answers could be never, sometimes, often and always. The amount of beverage intake with meals was also assessed (≤1, 2–3, 3–4 and >4 glasses). Subjects have also reported the number of fried and spicy food intake per week.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA and χ 2 test were used to compare continuous and categorical variables among different groups of main meal and snack frequency. In order to assess the normal distribution of variables, we used Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; all variables were normally distributed. Logistic regression in different models was used to investigate the relation between IBS symptoms and meal or snack frequency. We constructed crude and multivariable-adjusted models controlling for potential covariates. In the first model, age (continuous) and gender (categorical) were adjusted. Further adjustments in the second model were performed for physical activity (≥1 and <1 h/week), smoking status (current smoker, ex-smoker and non-smoker), marital status, education level, self-reported diabetes mellitus (yes, no), oral contraceptives pill usage (yes, no), supplement intake (yes, no), dental status, colitis (yes, no) and lactose intolerance (yes, no). Furthermore, we controlled for other variables like meal consumption regularity (regular, irregular), eating rate (<10, 10–20 and >20 min), weekly breakfast consumption (<5 and ≥5 times), intra-meal fluid intake (never or sometimes, often and always), weekly spicy food intake (never, 1–3, 4–6 and ≥7 times), fried food consumption (<4 and ≥4 times/week), quality of chewing (not well, well) and chocolate, tea and coffee consumption in the third model. BMI (kg/m2) was also considered in the fourth model. Stratified analyses by gender and BMI status were performed, and further appropriate adjustments in subgroups were done. Individuals in the first category of main meals, snacks or both of them were assumed as the reference group. All analyses were performed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 18.0; SPSS Inc.), and P-values <0·05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

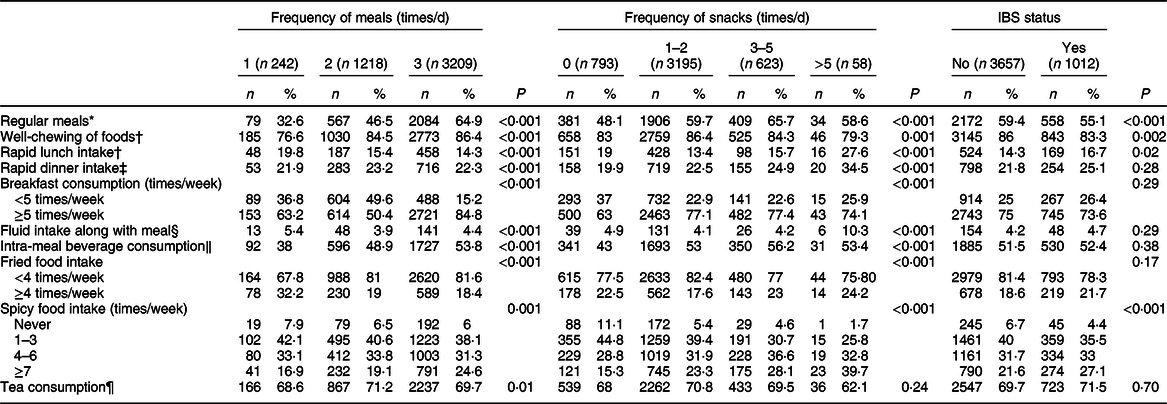

Mean age and weight of the study population were 36·5 (sd 8) years and 68·8 (sd 13·4) kg, respectively. A total of 2063 (44·2 %) males and 2606 (55·8 %) females aged 19–70 years were included in the analysis. Table 1 provides information about general characteristics of study participants in terms of meal or snack frequency as well as IBS status. In comparison with individuals consuming one main meal per day, participants who ate three meals per day were mostly young, and more than half of them were males and had lower percentages of smoking. They also had higher education levels and better dental status rather than aforementioned reference group. Individuals consuming more than five daily snacks were mostly younger, single, females, having higher education levels, taking more supplemental agents and having lower weight, BMI and smoking prevalence compared with participants without any snack consumption per each day. In comparison with healthy individuals, those with IBS were mostly females, had lower physical activity and had more colitis symptoms and lactose intolerance. IBS individuals had more intakes of supplement pills and more dental loss than healthy subjects. The distribution of participants based on different dietary habits across categories of meal or snack frequency and IBS is presented in Table 2. Compared with subjects eating one main meal, individuals with three daily main ones had better chewing, more regularly eating breakfasts, had more consumption of spicy and fried foods and consumed more intra-meal fluids. All eating-related habits except tea consumption were significantly different between different categories of snack frequency. IBS patients, in comparison with healthy subjects, took their lunch fast, ate their foods with less regularity, chewed the food less and had more consumption of spicy foods.

Table 1 General characteristics of study participants across categories of meal or snack frequency as well as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) status (n 4669)

OCP, oral contraceptives pill.

* Physically active: ≥1 h/week.

† Supplement intake including consumption of Fe, Ca, vitamins and other dietary supplements.

‡ Individuals who reported having abdominal pain, bloating, belching or diarrhoea after milk ingestion.

Table 2 Distribution of participants in terms of diet-related behaviours across categories of meal or snack frequency as well as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) status (n 4669)

* Individuals who reported regular meal consumption, often or always.

† Individuals who reported chewing foods, moderately or very well.

‡ Individuals who spent <10 min for meal consumption.

§ Individuals who reported ≥3 glasses of beverages with meals.

‖ Individuals who reported drinking fluids often or always.

¶ Individuals who reported drinking tea at least two glasses daily.

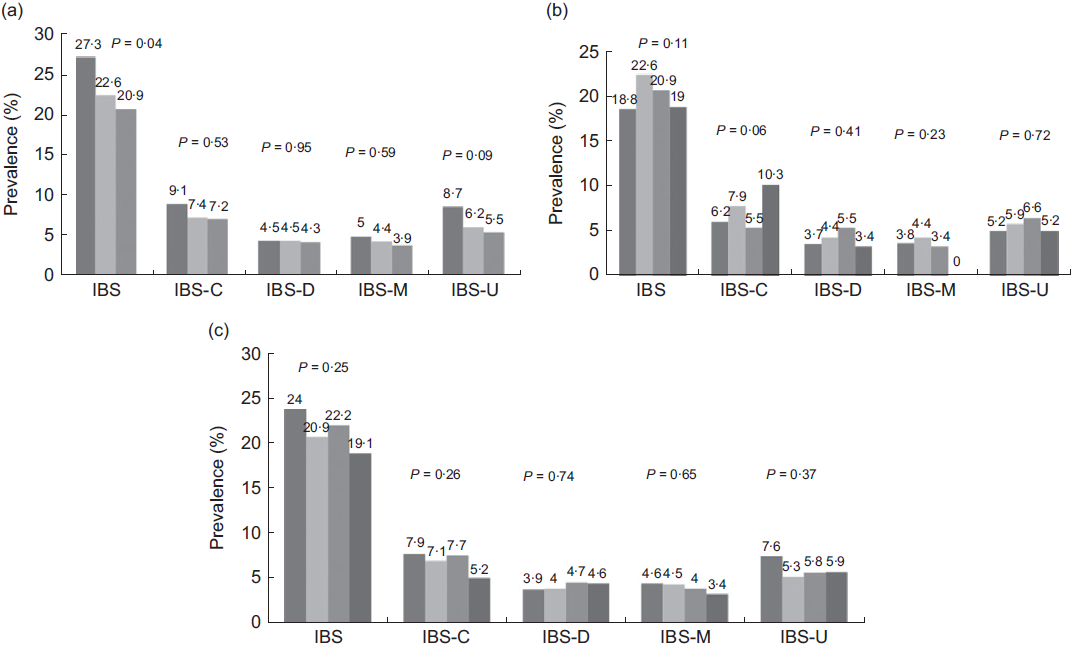

The prevalence of IBS among study subjects was 21·7 % (18·6 % in males and 24·1 % in females). The prevalence of IBS with constipation, IBS with diarrhoea, mixed IBS and un-subtyped IBS in our study was, respectively, 7·3, 4·4, 4·1 and 5·8 %. The prevalence across different categories of meal and snack consumption is shown in Fig. 2. Individuals eating three main meals every day had significantly lower prevalence of IBS compared with one or two main meals consumers (P = 0·04). The prevalence of other IBS subtypes was not statistically significant in terms of main meal or snack frequency or both of them.

Fig. 2 Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and its subtypes across categories of meal and snack frequency. (a) Main meal frequency (times/d); ![]() , 1;

, 1; ![]() , 2;

, 2; ![]() , 3. (b) Snack frequency (times/d);

, 3. (b) Snack frequency (times/d); ![]() , 0;

, 0; ![]() , 1–2;

, 1–2; ![]() , 3–5;

, 3–5; ![]() , >5. (c) Total meal and snacks (times/d) ;

, >5. (c) Total meal and snacks (times/d) ; ![]() , <3;

, <3; ![]() , 3–5;

, 3–5; ![]() , 6–7;

, 6–7; ![]() , ≥8. IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation, IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea, IBS-M, mixed irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-U, un-subtyped irritable bowel syndrome(a) Main meal frequency (times/d);

, ≥8. IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation, IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea, IBS-M, mixed irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-U, un-subtyped irritable bowel syndrome(a) Main meal frequency (times/d); ![]() , 1;

, 1; ![]() , 2;

, 2; ![]() , 3. (b) Snack frequency (times/d);

, 3. (b) Snack frequency (times/d); ![]() , 0;

, 0; ![]() , 1–2;

, 1–2; ![]() , 3–5;

, 3–5; ![]() , >5. (c) Total meal and snacks (times/d) ;

, >5. (c) Total meal and snacks (times/d) ; ![]() , <3;

, <3; ![]() , 3–5;

, 3–5; ![]() , 6–7;

, 6–7; ![]() , ≥8. IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation, IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea, IBS-M, mixed irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-U, un-subtyped irritable bowel syndrome

, ≥8. IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation, IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea, IBS-M, mixed irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-U, un-subtyped irritable bowel syndrome

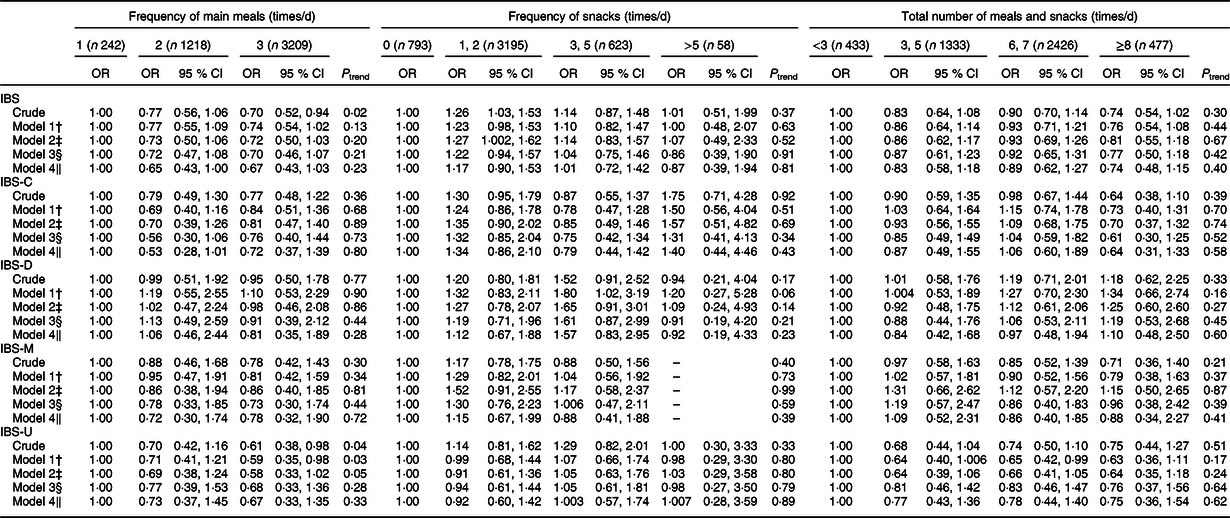

Multivariable-adjusted OR for IBS and its subtypes across different groups of meal and snack frequency are reported in Table 3. Individuals consuming three main meals had 30 % reduced risk of IBS (OR 0·70, 95 % CI 0·52, 0·94), compared to those with one main meal, in the crude model. After adjustments for all potential confounders this relation disappeared (OR 0·67, 95 % CI 0·43, 1·03). There was no other significant relation between IBS or its subtypes and different classes of meal, snack or total main meal and snack frequency, after taking all potential confounders into account.

Table 3 Multivariable-adjusted OR for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and IBS subtypes across categories of meal or/and snack frequency* (n 4669)

* IBS was assessed as having abdominal discomfort or pain at least sometimes in the last 3 months prior to the initiation of study with association of at least two of the followings: improvement with defaecation and changing in stool form or frequency.

† Model 1: adjusted for age and gender.

‡ Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, physical activity, smoking, marital status, education level, self-reported diabetes, oral contraceptives pill usage, supplement intake, dental status, colitis and lactose intolerance.

§ Model 3: further adjusted for meal regularity (non-regular, regular), eating rate (non-quick, quick or <10 min), breakfast consumption, intra-meal fluid intake (never or sometimes, often or always), spicy food intake (never, 1–3, 4–6 or ≥7 times/week), fried food intake (ordinal), frequency of fluid intake (ordinal), chewing efficiency (not well, well), chocolate consumption, tea consumption and coffee consumption.

‖ Model 4: further adjusted for BMI.

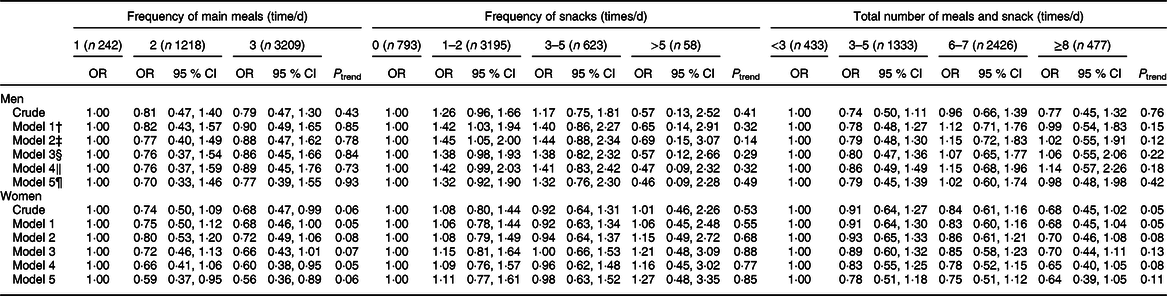

As depicted in Table 4, further gender-specified analysis revealed that women consuming three main meals per day had 32 % decreased likelihood of having IBS symptoms compared with one daily main meal takers (OR 0·68, 95 % CI 0·47, 0·99). This relation remained significant after adjustment for potential confounders (OR 0·56, 95 % CI 0·36, 0·89). No considerable association was found among male subjects. Dental status and presence of colitis were two confounders that made the relation statistically non-significant. Therefore, we performed stratified analysis according to the dental status among females, after excluding those with colitis (n 29) (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S1). Among women who lost one or more teeth, those who consumed three main meals per day had 44 % decreased likelihood of IBS symptoms (OR 0·56, 95 % CI 0·32, 0·98), compared with those with one main meal per day.

Table 4 Multivariable-adjusted OR for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) across categories of meal f or/and snack frequency separated by gender* (n 4669)

* IBS was assessed as having abdominal discomfort or pain at least sometimes in the last 3 months prior to the initiation of study with association of at least two of the followings: improvement with defaecation and changing in stool form or frequency.

† Model 1: adjusted for age.

‡ Model 2: adjusted for age, dental status and colitis.

§ Model 3: adjusted for age, physical activity, smoking, marital status, education level, self-reported diabetes, oral contraceptives pill usage, supplement intake, dental status, colitis and lactose intolerance.

‖ Model 4: further adjusted for meal regularity (non-regular, regular), eating rate (non-quick, quick or <10 min), breakfast consumption, intra-meal fluid intake (never or sometimes, often or always), spicy food intake (never, 1–3, 4–6 or ≥7 times/week), fried food intake (ordinal), frequency of fluid intake (ordinal), chewing efficiency (not well, well), chocolate consumption, tea consumption and coffee consumption.

¶ Model 5: further adjusted for BMI.

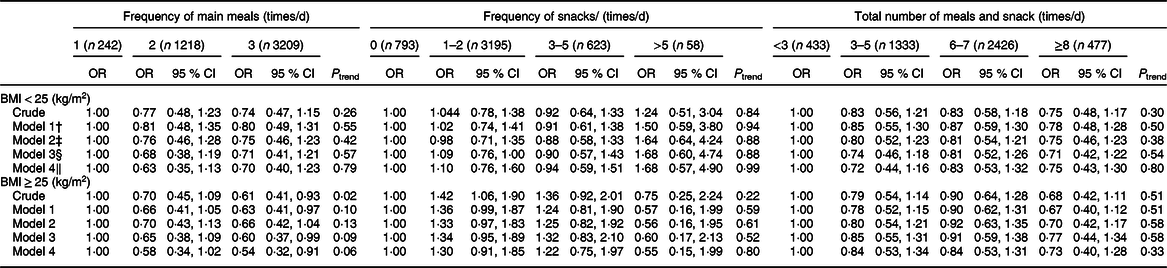

Multivariable-adjusted OR for IBS prevalence across different categories of meal/snack frequency, separated by BMI status, are shown in Table 5. In obese or overweight subjects (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), a 39 % (OR 0·61, 95 % CI 0·41, 0·93) decreased likelihood of IBS was found in the highest category of main meal consumption compared with the reference group (one main meal per day). After making adjustment for age and gender, this association was still significant (OR 0·63, 95 % CI 0·41, 0·97). Adjustment for other confounding variables revealed that overweight and obese individuals who consumed three main meals had 46 % (OR 0·54, 95 % CI 0·32, 0·91) decreased likelihood of IBS symptoms in comparison with those who ate one main meal. Adjustment for marital status made the relation insignificant. So, we stratified the analysis by marital status among overweight and obese individuals (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S2). Among married overweight and obese participants, those who consumed three main meals per day had a 43 % reduced likelihood of IBS in comparison with those taking one main meal daily (OR 0·57, 95 % CI 0·33, 0·98). When we performed stratified analysis by gender, we observed that the number of main meals was not significantly associated with IBS among married overweight and obese males or females, neither in crude nor in adjusted models (as shown in online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S3).

Table 5 Multivariable-adjusted OR for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) across categories of meal or/and snack frequency separated by BMI status* (n 4669)

* IBS was assessed as having abdominal discomfort or pain at least sometimes in the last 3 months prior to the initiation of study with association of at least two of the followings: improvement with defaecation and changing in stool form or frequency.

† Model 1: adjusted for age and gender.

‡ Model 2: adjusted for age, gender and marital status.

§ Model 3: adjusted for age, gender, physical activity, smoking, marital status, education level, self-reported diabetes, oral contraceptives pill usage, supplement intake, dental status, colitis and lactose intolerance.

‖ Model 4: further adjusted for meal regularity (non-regular, regular), eating rate (non-quick, quick or <10 min), breakfast consumption, intra-meal fluid intake (never or sometimes, often or always), spicy food intake (never, 1–3, 4–6 or ≥7 times/week), fried food intake (ordinal), frequency of fluid intake (ordinal), chewing efficiency (not well, well), chocolate consumption, tea consumption and coffee consumption.

Discussion

We evaluated the relation of meal and snack frequency with IBS and its subtypes in a large group of Iranian adults and found that there was no significant relation between the frequency of main meals or snacks with IBS symptoms. However, a declined risk of IBS symptoms was found among female participants consuming three main meals each day based on the gender-stratified analysis. In overweight or obese participants, having more main meals was also associated with decreased odds of IBS. Moreover, we observed that among female individuals with colitis and few teeth, the number of meals was low and the prevalence of IBS was high. So, inflammation of the teeth and colon might be associated with meal frequency and IBS. It would be possible that they had fewer meals because they had fewer teeth or because of colitis symptoms; this point should be considered while interpreting our findings. We used Rome III diagnostic criteria in order to estimate the prevalence of IBS as 21·7 %. However, it must be taken into account that this prevalence could be considerably lower in terms of recently released Rome IV criteria for IBS definition. Since IBS is one of the most common GI disorders with high prevalence and considerable economic burden(Reference Jahangiri, Jazi and Keshteli3,Reference Roshandel, Rezailashkajani and Shafaee11) , it might be advisable for populations to have more meals in order to decrease the prevalence of IBS symptoms, especially in female individuals. Findings of several previous investigations were consistent with the current study(Reference Khademolhosseini, Mehrabani and Nejabat5,Reference Kim and Ban24,Reference Okami, Kato and Nin25) . For instance, in a cross-sectional study among 1717 Korean students, Kim & Ban(Reference Kim and Ban24) reported that individuals suffering from IBS missed their daily meals more frequently compared with healthy subjects. Also, skipping meals was significantly more prevalent in IBS middle-aged patients rather than normal individuals in another cross-sectional investigation(Reference Khademolhosseini, Mehrabani and Nejabat5). Okami et al.(Reference Okami, Kato and Nin25) reported the same finding from nursing and medical school students in Japan. In contrast, several studies failed to prove any significant association(Reference Chirila, Petrariu and Ciortescu16,Reference Khayyatzadeh, Kazemi-Bajestani and Mirmousavi17,Reference Omagari, Murayama and Tanaka20) . In a cross-sectional study among 193 urban Romanian adults, meal or snack frequency was not associated with IBS. However, the small number of sample size and not considering all potential confounders might influence this finding(Reference Chirila, Petrariu and Ciortescu16). Khayyatzadeh et al.(Reference Khayyatzadeh, Kazemi-Bajestani and Mirmousavi17) have studied 988 Iranian adolescent girls aged 12–18 years and found that neither main meals nor snack frequency was a significant association with IBS symptoms in crude or adjusted models. Moreover, in a cross-sectional study among 245 Japanese females aged 18–32 years, skipping meals had no significant association with IBS. Again, small sample size should be taken into account while interpreting this finding(Reference Omagari, Murayama and Tanaka20).

The observed gender disparity in the associations in the current study might be related to higher prevalence of IBS among women. Another reason might be the difference in accuracy of reporting dietary habits among females and males; women might report dietary behaviours more accurately than men.

The exact pathophysiological mechanisms explaining inverse relations between meal or snack frequency and IBS symptoms have yet to be explored. One possible theory would be related to GI motility. It has been suggested that skipping meal consumption was associated with the loss of gastro-colonic reflex and impacted faeces(Reference Hosoda26). By increasing frequency of main meal taking, this reflex might be improved and would lead to decreased symptoms of IBS. Further prospective studies are necessary to prove a causal relation.

Investigating a large sample size of adults and considering several potential confounders were the strengths of our study. Also, we recruited participants from different job categories and excluded faculty members of teaching hospitals or research institutes to decrease probable conflict of interests. However, the current investigation had some limitations. Cross-sectional design of the study was the most important limitation which prevented us to have a causal relationship. Furthermore, the possibility of reverse causality should be considered in such kind of studies in a way that individuals with IBS might reduce the frequency of their meals or snacks in order to attenuate the symptoms. Recall bias is an inevitable disadvantage in any researches which recall of events is required. We tried our best to consider all potential confounders, but some other factors might negatively affect our findings. Almost all Iranians are muslims and have religious prohibitions that preclude the use of alcohol. Therefore, alcohol consumption, an important covariate for IBS, in our study population was very low, and data in this regard were not collected in the current study. Since this investigation was conducted among Iranian population, generalisation of results to other nations must be cautiously done.

In conclusion, our findings suggested that although there was no significant association between the numbers of main meals and snacks with IBS symptoms, a small inverse relation was found in terms of main meal and IBS in females and overweight or obese individuals. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these associations.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments: The authors wish to thank all staff of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences who kindly participated in our study and staff of Public Relations Unit, and other authorities of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for their excellent cooperation. Financial support: The financial support for conception, design, data analysis and manuscript drafting comes from Food Security Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. Conflict of interest: None of the authors had any personal or financial conflicts of interest. Authorship: Study concept and design: M.V., P.S., A.E. and P.A; acquisition of data: P. S. and M.V.; analysis and interpretation of data: M.V., P.S. and A.K; drafting of the manuscript: P.S. and M.V.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: M.V., P.S., A.K., H.D., A.E. and P.A.; statistical analysis: M.V. and P.S.; administrative, technical and material support: P.S., P.A., A.E. and H.D.; supervision: P.S., A.E., H.D., A.K. and P.A. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Regional Bioethics Committee, affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Consent for publication: Consent form was obtained from each participant. Availability of data and materials: The data sets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due confidential issues but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002967