Introduction

Globally, mental disorders account for almost 20% of disease burden, with associated annual costs projected to be US$6 trillion by 2030 (Campion et al., Reference Campion, Javed, Lund, Sartorius, Saxena, Marmot and Udomratn2022). Accordingly, the United Nations (UN) has put forth the ambitious goal of achieving universal mental health care coverage by 2030 as a part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018; United Nations, 2015). However, in 2020, which marked the halfway point to the 2030 goal, only 2% of global government health expenditure was allocated to mental health, with significantly less in low-income countries (Campion et al., Reference Campion, Javed, Lund, Sartorius, Saxena, Marmot and Udomratn2022; WHO, 2021). This suggests that goals to increase access to mental health treatments alone are insufficient to reduce the burden of poor mental health globally (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018; Rose-Clarke et al., Reference Rose-Clarke, Gurung, Brooke-Sumner, Burgess, Burns, Kakuma and Lund2020).

The World Health Organization (WHO) argues that ‘the twin aims of improving mental health and lowering the personal and social costs of mental ill-health can only be achieved through a public health approach’ (Mehta, Croudace, & Davies, Reference Mehta, Croudace and Davies2015; WHO, 2005). Public mental health has become progressively prominent in international health policy. For example, prevention of mental disorders, promotion of mental wellbeing, and treatment of disorders are central to the WHO's Mental Health Action Plan (WHO, 2013). Similarly, the World Psychiatric Association made public mental health and intervention implementation a central part of its 2020–2023 action plan (World Psychiatric Association, 2020). However, for most nations, the majority of mental health investment still lay in psychiatric hospital care in 2020, with less than 20% of expenditure going towards primary care, mental disorder prevention, or well-being promotion (Campion et al., Reference Campion, Javed, Lund, Sartorius, Saxena, Marmot and Udomratn2022; WHO, 2021). In 2019, the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Research announced that one of their priorities was to identify the most effective interventions, outside of the National Health Service (NHS), aimed at enabling populations to achieve good mental health and to prevent mental health problems (National Institute for Health and Care Research, 2022).

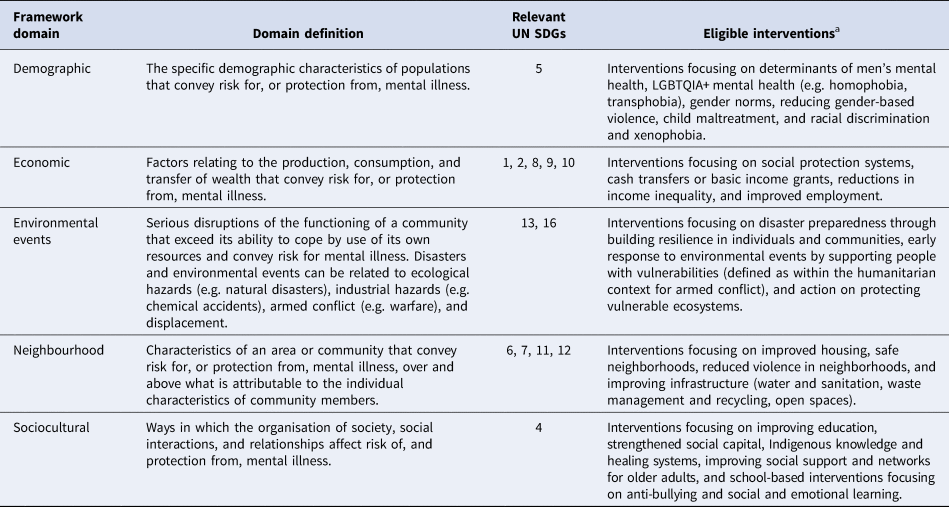

Mental disorders are strongly socially determined (Blas & Kurup, Reference Blas and Kurup2010; Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018; WHO, 2014), suggesting that approaches tackling social determinants may be effective (Rose-Clarke et al., Reference Rose-Clarke, Gurung, Brooke-Sumner, Burgess, Burns, Kakuma and Lund2020). Addressing the social determinants of mental disorders also aligns with the UN SDGs (Campion et al., Reference Campion, Javed, Lund, Sartorius, Saxena, Marmot and Udomratn2022; Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018). In 2018, Lund et al., developed a novel conceptual framework that summarized the major social determinants of mental disorders and linked them with the UN SDGs (see Fig. 1). This framework was applied through a large umbrella review, which primarily described observational data of mental health outcomes linked to social determinants (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018). The review highlighted the synergy between many social determinants of mental disorders and the SDGs. For example, across the literature, female gender was associated with increased risk of depression and anxiety, demonstrating the importance of SDG 5 – to ‘achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’ – for population-level mental health.

Figure 1. Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: a conceptual framework by Lund et al. (Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018).

There is now a need establish an evidence-base to determine the effectiveness of interventions which target the social determinants of mental health and the SDGs. In their review, Lund et al. (Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018) put forth a number of intervention candidates, and, following publication of the review, the UK Academy of Medical Sciences and the Inter-Academy Partnership for Health convened an international workshop in London to identify intervention priorities for each framework domain moving forward (Rose-Clarke et al., Reference Rose-Clarke, Gurung, Brooke-Sumner, Burgess, Burns, Kakuma and Lund2020). However, the effectiveness of these proposed interventions was not considered, and the evidence had not been synthesized.

While Lund's framework was previously used in a review of national-level interventions, evidence presented was mostly observational and from higher or upper-middle income countries (Shah et al., Reference Shah, Walker, Naik, Rajan, O'Hagan, Black and Stansfield2021). Using the same conceptual framework, we aimed to strengthen the evidence base by conducting a systematic review of reviews including Lund et al. (Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018) and Rose-Clarke et al. (Reference Rose-Clarke, Gurung, Brooke-Sumner, Burgess, Burns, Kakuma and Lund2020) et al.'s proposed intervention priorities, with evidence from community-level interventions, low-, middle-, and high-income country settings, and study designs with comparison groups.

Methods

A systematic review of reviews was conducted, in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Checklist (see Supplementary File 1). A protocol was pre-registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022361534).

Search strategy and selection criteria

PubMed, PsycInfo, and Scopus were searched from 01 January 2012 until 05 October 2022, to identify the most recent evidence. The search strategies (Supplementary File 2) were developed with input of an academic librarian. Citation follow-up and expert consultation were conducted. We contacted all authors of the Lund et al. review (Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018), and the corresponding author for each included review, to request additional studies.

Study designs

Reviews which utilized a systematic methodology, published in any language, were eligible for inclusion. Non-systematic reviews and primary data studies were excluded. Reviews from the grey literature were excluded as we aimed to gather peer-reviewed evidence only.

Participants

Participants of all ages from the general population were eligible, including participants with mental disorders/symptoms. Given the broader public mental health focus of the research, participant groups with little generalizability to wider populations (e.g. students at a specific College only), were excluded.

Interventions

Only the interventions suggested by Lund et al. (Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018), and the intervention priorities identified in the international workshop (Rose-Clarke et al., Reference Rose-Clarke, Gurung, Brooke-Sumner, Burgess, Burns, Kakuma and Lund2020), were eligible for inclusion. We reviewed these specified interventions (see Table 1) as they mapped onto the conceptual framework, aligned with the SDGs, and the evidence base for these recommended interventions had not been previously synthesized. Interventions focusing on direct treatment of mental disorders were excluded, except for psychosocial interventions aiming to support vulnerable people in response to environmental events.

Table 1. Eligible interventions by framework domain

UN SDGs, United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

a Eligible interventions based on Lund et al. (Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018) and Rose-Clarke et al. (Reference Rose-Clarke, Gurung, Brooke-Sumner, Burgess, Burns, Kakuma and Lund2020).

Comparisons

Reviews were included if more than half of the studies had a comparator/control group (active or inactive).

Outcomes

Reviews had to report on relevant mental health outcome data at baseline and post-intervention. Outcomes of interest were changes in the severity, course, or prevalence of mental disorders, and incidence of mental disorder onset. Mental disorders included depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, psychosis, child/adolescent behavioral/developmental disorders, childhood internalizing/externalizing disorders, suicide/suicidal behaviors, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and dementia. Mental health outcome measures needed to be obtained using valid and reliable scales suitable for the population under study, standardized interviews, or more direct measures of the mental disorder such as a clinician diagnosis or health records. Indicators of these mental disorders, such as psychological distress or cognitive functioning, were included. Aspects of general mental well-being were excluded (e.g. quality of life).

Study screening and selection

Study screening was conducted independently by two authors (TKO and MTN) using Covidence. Applying the selection criteria, the articles were included or excluded based on the title and abstract, or a consequent full-text review. Google Translate was used to assess the eligibility of articles not published in English (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Kuriyama, Anton, Choi, Fournier, Geier and Sun2019).

One author (TKO) screened the titles and abstracts of new references identified through reference lists of included reviews, as well as new articles provided by contacted experts. Two authors (TKO and MTN) then screened the full-text of these new articles.

The authors (TKO and MTN) resolved any eligibility discrepancies through discussion, only proceeding to next stages once 100% agreement was reached. A third author (JDM) was consulted where consensus could not be reached.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted in Excel, using a form designed and tested by the authors. Six authors (TKO, LM, MTN, GC, HGJ, and DA) independently extracted data from a sub-sample of the included studies (n = 5 reviews) ensuring agreement was achieved through checks and discussions. The remainder of the data extraction was divided and conducted independently by the six authors.

Quality assessments

The AMSTAR-2 checklist was used for quality assessments of included reviews. The 16-item checklist allows a rating of overall confidence in the results of the review to be made (high, moderate, low, or critically low). Assessments were conducted independently by five authors (TKO, LM, MTN, GC, and HGJ) on a sample of the included reviews (n = 5 reviews), ensuring agreement was achieved through checks and discussion. The remainder of the assessments were divided and conducted independently by the five authors. The seven critical items on the checklist were also independently rated for each review by a second author (TKO or LM), and the inter-rater reliability was 92%. A third author (JDM) was consulted to achieve consensus where there were discrepancies.

Synthesis

The populations, interventions, and outcome measures were heterogeneous across studies; therefore, we reported results in the form of a qualitative synthesis. We extracted magnitude of effect data and meta-analyses as provided by original authors in the studies reviewed.

Results

Database searches identified 20 864 articles; 5477 duplicates were removed and 14 751 did not meet the inclusion criteria based on information in the title or abstract. The full-text of 636 articles were assessed for eligibility; 82 met the inclusion criteria. Articles which were excluded by full-text (n = 554) are provided in Supplementary File 3. Seven eligible reviews were identified in the reference lists of the included reviews. After contacting experts and corresponding authors of included studies, 12 new suggestions were eligible for inclusion. A total of 101 reviews were included in the review (PRISMA flow diagram in Supplementary File 4). Table 2 presents a summary of the included reviews and detailed descriptions are provided in Supplementary File 5.

Table 2. Summary of included reviews (N = 101)

n, number of reviews.

Confidence in the review results

Of the 101 included reviews, 23 were rated as having high confidence, 14 as moderate, 24 as low, and 40 as critically low confidence, on the AMSTAR-2. The full AMSTAR-2 ratings are presented in Supplementary File 6.

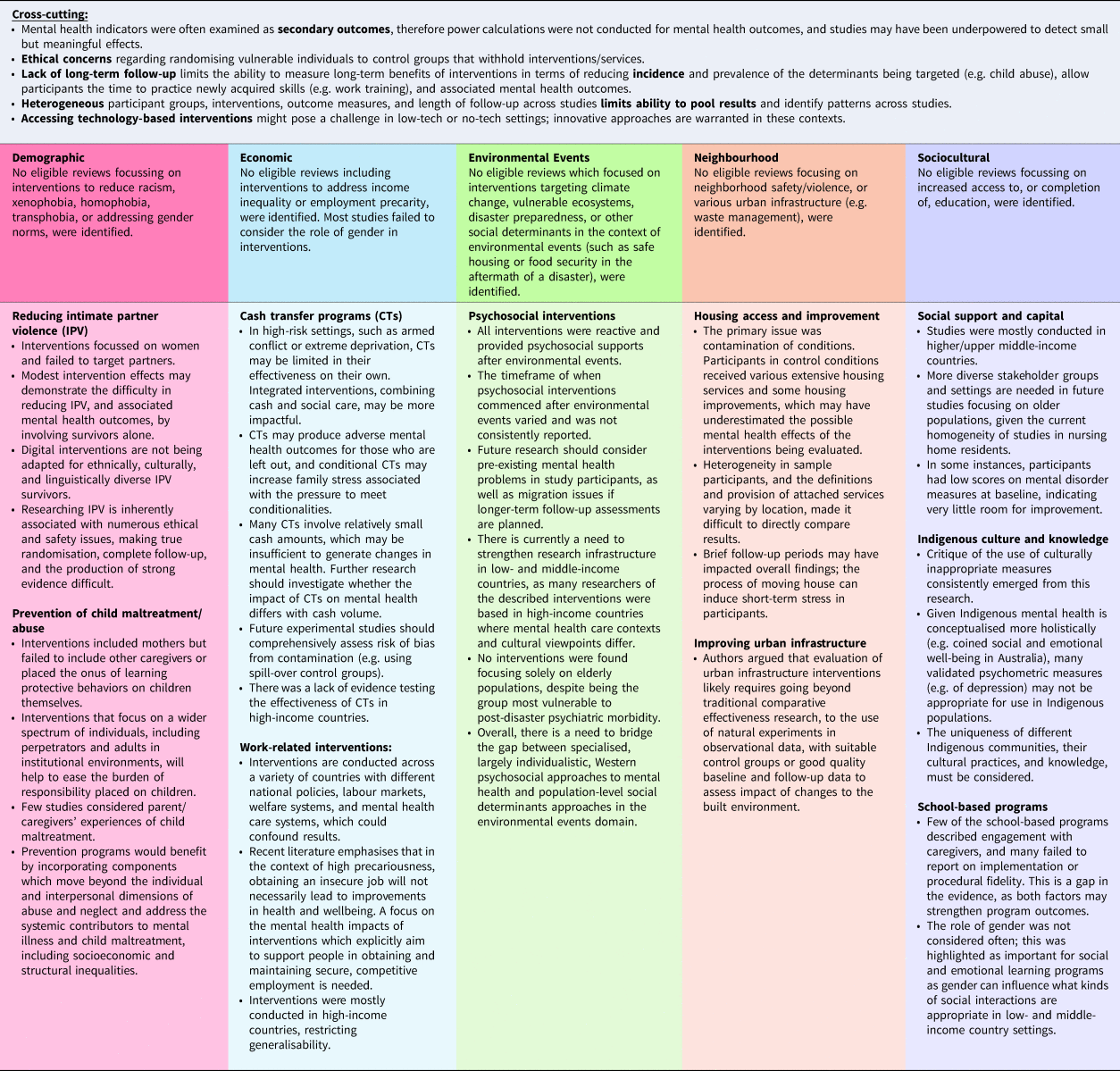

Findings from the moderate and high confidence reviews (n = 37) are the focus of the results section and are presented in Table 3. Key gaps, challenges, and methodological issues identified are outlined in Table 4.

Table 3. Key characteristics and findings from moderate and high confidence reviews

a CI = confidence interval; ES = effect size; MD = mean difference; OR = odds ratio; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; QEs = quasi-experiments; RCTs = randomized controlled trials; S.D. = standard deviation; S.E. = standard error; SMD = standard mean difference.

b Quality of the studies/evidence according to the original review authors.

Review author and publication year; relevant number of studies/total number of studies in the review; study designs.

Table 4. Cross-cutting, domain-specific, and intervention-specific gaps, challenges, and methodological issues

Demographic domain

Fifteen reviews with Demographic domain interventions were identified (Asgary, Emery, & Wong, Reference Asgary, Emery and Wong2013; Branco, Altafim, & Linhares, Reference Branco, Altafim and Linhares2021; Chen & Chan, Reference Chen and Chan2016; Drew, Morgan, Pollock, & Young, Reference Drew, Morgan, Pollock and Young2020; Efevbera, McCoy, Wuermli, & Betancourt, Reference Efevbera, McCoy, Wuermli and Betancourt2018; Emezue, Chase, Udmuangpia, & Bloom, Reference Emezue, Chase, Udmuangpia and Bloom2022; Fang, Barlow, & Zhang, Reference Fang, Barlow and Zhang2022; Goldstein, Rosen, Howlett, Anderson, & Herman, Reference Goldstein, Rosen, Howlett, Anderson and Herman2020; Linde et al., Reference Linde, Bakiewicz, Normann, Hansen, Lundh and Rasch2020; Rivas et al., Reference Rivas, Ramsay, Sadowski, Davidson, Dunne, Eldridge and Feder2015; Spencer, Stith, & King, Reference Spencer, Stith and King2021; Stephens-Lewis et al., Reference Stephens-Lewis, Johnson, Huntley, Gilchrist, McMurran, Henderson and Gilchrist2021; Van Parys, Verhamme, Temmerman, & Verstraelen, Reference Van Parys, Verhamme, Temmerman and Verstraelen2014; Waid, Cho, & Marsalis, Reference Waid, Cho and Marsalis2022; Walsh, Zwi, Woolfenden, & Shlonsky, Reference Walsh, Zwi, Woolfenden and Shlonsky2015). Examples of demographic determinants of mental health include age and gender. SDG 5 (achieving gender equality) is particularly relevant to this domain. Four reviews were given a moderate or high confidence rating.

Reducing intimate partner violence

Three reviews focused on reducing intimate partner violence (IPV). An earlier review (Linde et al., Reference Linde, Bakiewicz, Normann, Hansen, Lundh and Rasch2020) reported no evidence that eHealth interventions reduced depression or PTSD in women exposed to IPV, compared with use of control websites or standard care. A more recent review (Emezue et al., Reference Emezue, Chase, Udmuangpia and Bloom2022), including digital interventions for female IPV victims, reported small but statistically significant reductions in depression and anxiety symptoms, but not PTSD, at 3-month follow-up. A final review looking at one-on-one advocacy support interventions for women who have experienced IPV reported inconsistent evidence that advocacy has a beneficial impact on mental health outcomes for this population (Rivas et al., Reference Rivas, Ramsay, Sadowski, Davidson, Dunne, Eldridge and Feder2015). While no advocacy intervention effects were detected when measuring depression and physical abuse as continuous outcomes, studies which measured these as dichotomous outcomes reported that significantly fewer women developed depression, and were less likely to experience physical abuse, at the end of a brief advocacy intervention period. There was significant evidence that brief advocacy interventions reduced psychological distress at three-to-four months follow-up, but intensive advocacy interventions showed no statistically significant effect.

Prevention of child abuse

A review (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Zwi, Woolfenden and Shlonsky2015) of school-based sexual abuse education programs reported no evidence of changes in anxiety in intervention participants compared to control participants. Longer-term intervention effects on the prevention of sexual abuse and mental health outcomes could not be determined due to the collection of immediate program outcomes only.

Economic domain

Twenty-four reviews with Economic domain interventions were identified (Audhoe, Hoving, Sluiter, & Frings-Dresen, Reference Audhoe, Hoving, Sluiter and Frings-Dresen2010; Bond, Drake, & Pogue, Reference Bond, Drake and Pogue2019; Charzyńska, Kucharska, & Mortimer, Reference Charzyńska, Kucharska and Mortimer2015; Evans, Lund, Massazza, Weir, & Fuhr, Reference Evans, Lund, Massazza, Weir and Fuhr2022; Frederick & VanderWeele, Reference Frederick and VanderWeele2019; Gayed et al., Reference Gayed, Milligan-Saville, Nicholas, Bryan, LaMontagne, Milner and Harvey2018; Little et al., Reference Little, Roelen, Lange, Steinert, Yakubovich, Cluver and Humphreys2021; Lund et al., Reference Lund, De Silva, Plagerson, Cooper, Chisholm, Das and Patel2011; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Goldberg, Braude, Dougherty, Daniels, Ghose and Delphin-Rittmon2014; McGuire, Kaiser, & Bach-Mortensen, Reference McGuire, Kaiser and Bach-Mortensen2022; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Kapur, Hawton, Richards, Metcalfe and Gunnell2017; Nieuwenhuijsen et al., Reference Nieuwenhuijsen, Verbeek, Neumeyer-Gromen, Verhoeven, Bültmann and Faber2020; Pachito et al., Reference Pachito, Eckeli, Desouky, Corbett, Partonen, Rajaratnam and Riera2018; Pega et al., Reference Pega, Pabayo, Benny, Lee, Lhachimi and Liu2022; Puig-Barrachina et al., Reference Puig-Barrachina, Giró, Artazcoz, Bartoll, Cortés-Franch, Fernández and Borrell2020; Ridley, Rao, Schilbach, & Patel, Reference Ridley, Rao, Schilbach and Patel2020; Ruotsalainen, Verbeek, Mariné, & Serra, Reference Ruotsalainen, Verbeek, Mariné and Serra2014; Suijkerbuijk et al., Reference Suijkerbuijk, Schaafsma, van Mechelen, Ojajärvi, Corbière and Anema2017; Suto, Balogun, Dhungel, Kato, & Takehara, Reference Suto, Balogun, Dhungel, Kato and Takehara2022; van Rijn, Carlier, Schuring, & Burdorf, Reference van Rijn, Carlier, Schuring and Burdorf2016; Walton & Hall, Reference Walton and Hall2016; Wollburg, Steinert, Reeves, & Nye, Reference Wollburg, Steinert, Reeves and Nye2023; Zaneva, Guzman-Holst, Reeves, & Bowes, Reference Zaneva, Guzman-Holst, Reeves and Bowes2022; Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Garman, Avendano-Pabon, Araya, Evans-Lacko, McDaid and Lund2021). Examples of economic determinants of mental health include financial strain, unemployment, and relative deprivation. SDG 1 (no poverty) and 8 (decent work and economic growth) are examples of relevant SDGs for this domain. Thirteen reviews were given a moderate- or high-confidence rating.

Cash transfer programs

Six reviews assessed cash transfer interventions (CTs); three focused on children and young people (Little et al., Reference Little, Roelen, Lange, Steinert, Yakubovich, Cluver and Humphreys2021; Zaneva et al., Reference Zaneva, Guzman-Holst, Reeves and Bowes2022; Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Garman, Avendano-Pabon, Araya, Evans-Lacko, McDaid and Lund2021), and three on participants of all ages (McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Kaiser and Bach-Mortensen2022; Pega et al., Reference Pega, Pabayo, Benny, Lee, Lhachimi and Liu2022; Wollburg et al., Reference Wollburg, Steinert, Reeves and Nye2023), in low- and middle-income countries. Overall, CTs were associated with improved mental health outcomes, and unconditional CTs were reported to have a larger effect than conditional CTs which require participants to comply with certain conditions such as school attendance or healthcare visits (McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Kaiser and Bach-Mortensen2022; Wollburg et al., Reference Wollburg, Steinert, Reeves and Nye2023; Zaneva et al., Reference Zaneva, Guzman-Holst, Reeves and Bowes2022). One review noted that conditional CTs may be harmful for adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries, as they can increase responsibilities and create stress (Zaneva et al., Reference Zaneva, Guzman-Holst, Reeves and Bowes2022). The effect of CTs were reported to be moderated by their absolute size and their size relative to previous income, with larger amounts of money associated with more positive effects (McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Kaiser and Bach-Mortensen2022; Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Garman, Avendano-Pabon, Araya, Evans-Lacko, McDaid and Lund2021). One review reported that mental health improvements did not appear to be sustained at 2–9 years follow-up (Wollburg et al., Reference Wollburg, Steinert, Reeves and Nye2023).

Increasing or maintaining employment

Three reviews focused on interventions which aimed to increase or maintain employment. One review included adults who were unemployed due to severe mental illness (Suijkerbuijk et al., Reference Suijkerbuijk, Schaafsma, van Mechelen, Ojajärvi, Corbière and Anema2017) and reported reductions in negative symptoms and general psychopathology for people in prevocational training and supported employment compared to receiving psychiatric care only. Another review (Nieuwenhuijsen et al., Reference Nieuwenhuijsen, Verbeek, Neumeyer-Gromen, Verhoeven, Bültmann and Faber2020) assessed work-directed interventions which aim to ameliorate the consequences of depressive disorders on the ability to work, by modifying the job tasks or temporarily reducing working hours. Overall, the effectiveness of work-directed interventions on mental health outcomes was inconsistent. Another review assessing work-based programs in general populations (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Lund, Massazza, Weir and Fuhr2022) reported that interventions with a skill-based component showed promise for positive effect on depression and anxiety measures.

Improving working conditions

Three reviews focused on interventions which aimed to improve working conditions, mostly in high-income countries. Healthcare workers were the focus of one review (Ruotsalainen et al., Reference Ruotsalainen, Verbeek, Mariné and Serra2014); only interventions improving work schedules resulted in mental health benefits, with two studies reporting reduced stress levels for workers assigned shorter or interrupted work schedules.

Another review (Suto et al., Reference Suto, Balogun, Dhungel, Kato and Takehara2022) included workers from a variety of sectors. For interventions in which weekly working hours were reduced by 25%, intervention participants experienced decreased stress. For interventions which involved self-rostering and gave participants choice over their work activities, intervention participants experienced reduced somatic symptoms and mental distress at 12-month follow-up. In interventions focusing on supervisory/employee training designed to reduce work-family conflict, intervention participants experienced reduced negative affect. The Workplace Triple p program, which aimed to reduce work-family conflict and improve family functioning, was reported to reduce participant's work stress, parental distress, depression, and anxiety symptoms, and reduce their children's behavior problems, up to 4-months follow-up. Employee assistance programs, offering individualized counseling, did not significantly reduce workplace distress or at-risk alcohol use in participants, but led to reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety.

One review (Pachito et al., Reference Pachito, Eckeli, Desouky, Corbett, Partonen, Rajaratnam and Riera2018) assessed workplace lighting interventions in office and hospital workers. Only one lighting intervention showed positive effects; glasses with mounted light-emitting diodes providing blue-enriched light improved mood in indoor workers compared to no treatment.

Reducing the impact of job loss, debt, and financial difficulties

One review focused on interventions which aimed to reduce the impact of job loss, debt, and financial difficulties (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Kapur, Hawton, Richards, Metcalfe and Gunnell2017). There was consistent evidence that short, 1-to-2-week Job Club interventions involving job skills training seminars can reduce depressive symptoms in high-risk, unemployed people, for up to two years. Effects were small but strongest among those at increased risk of depression at baseline. There was some evidence that reduced depressive symptoms were associated with re-employment, reduction of financial strain, and job search preparedness.

Environmental Events domain

Nineteen reviews with Environmental Events interventions were identified (Al-Tamimi & Leavey, Reference Al-Tamimi and Leavey2022; Alzaghoul, McKinlay, & Archer, Reference Alzaghoul, McKinlay and Archer2022; Brown, de Graaff, Annan, & Betancourt, Reference Brown, de Graaff, Annan and Betancourt2017a; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Witt, Fegert, Keller, Rassenhofer and Plener2017b; Coombe et al., Reference Coombe, Mackenzie, Munro, Hazell, Perkins and Reddy2015; Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Benedetto, Harris, Boland, Christian, Hill and Clegg2021; Fu & Underwood, Reference Fu and Underwood2015; Gillespie et al., Reference Gillespie, Banegas, Maxwell, Chan, Darawshy, Wasil and Gewirtz2022; Gwozdziewycz & Mehl-Madrona, Reference Gwozdziewycz and Mehl-Madrona2013; Kiss et al., Reference Kiss, Quinlan-Davidson, Pasquero, Tejero, Hogg, Theis and Hossain2020; Le Roux & Cobham, Reference Le Roux and Cobham2022; Li et al., Reference Li, Shi, Gao, Shi, Feng, Liang and Hall2022; Lipinski, Liu, & Wong, Reference Lipinski, Liu and Wong2016; Lopes, Macedo, Coutinho, Figueira, & Ventura, Reference Lopes, Macedo, Coutinho, Figueira and Ventura2014; Natha & Daiches, Reference Natha and Daiches2014; O'Sullivan, Bosqui, & Shannon, Reference O'Sullivan, Bosqui and Shannon2016; Pfefferbaum, Nitiéma, & Newman, Reference Pfefferbaum, Nitiéma and Newman2019; Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2018a, Reference Purgato, Gross, Betancourt, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon and Barbui2018b). Examples of environmental determinants of mental health include natural disasters, industrial disasters, war or conflict, climate change, and forced migration. SDG 13 (climate action) and 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions) are examples of relevant SDGs in this domain. Six reviews were given a moderate or high confidence rating.

Group-based psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events in humanitarian settings

Two reviews focused on group-based psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents who had been exposed to traumatic events in humanitarian settings in low- and middle-income countries (Alzaghoul et al., Reference Alzaghoul, McKinlay and Archer2022; Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gross, Betancourt, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon and Barbui2018b). In one review, a skills-based program derived from trauma-focused CBT, was associated with statistically significant and clinically meaningful reductions in PTSD and depression scores compared to waitlist groups (Alzaghoul et al., Reference Alzaghoul, McKinlay and Archer2022). Meta-analysis of PTSD symptoms in another review showed a small, beneficial effect of focused psychosocial support interventions v. waiting list at four weeks post-intervention (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gross, Betancourt, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon and Barbui2018b). No difference in depressive and anxiety symptoms was found between treatment and control groups at four week follow-up (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gross, Betancourt, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon and Barbui2018b).

Psychosocial interventions for individuals of all ages exposed to environmental events

Two reviews focused on psychosocial interventions for individuals of all ages who had been exposed to a variety of environmental events. One of these reviews focused on events in China, including the Wenchuan earthquake and the COVID-19 pandemic, and considered a range of psychosocial and traditional Chinese interventions (Li et al., Reference Li, Shi, Gao, Shi, Feng, Liang and Hall2022). Overall, interventions led to improvement in all psychological outcomes assessed (e.g. anxiety, suicide risk, depression, and PTSD). Statistical significance and the magnitude of effects were not always reported, but the authors indicate that most effect sizes were not large.

Another review (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2018a) summarized a range of psychological interventions with common elements (e.g. psychoeducation and coping skills) following natural disasters and man-made disasters such as genocide, armed conflict, and war, in low- and middle-income countries. For adults, psychological therapies substantially reduced PTSD symptoms, depression symptoms, and moderately reduced anxiety, compared to control conditions. In children and adolescents, there was very low-quality evidence for lower PTSD symptoms scores in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) conditions compared to control conditions.

A final review summarized various psychological therapies following infectious disease outbreaks, with all but one study focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Benedetto, Harris, Boland, Christian, Hill and Clegg2021). Meta-analyses conducted suggested that different psychological support interventions have potential to reduce levels of anxiety and depression in those exposed to mass infectious disease, but not levels of stress.

Parenting programs for displaced families in humanitarian settings

Parenting programs for displaced families (Gillespie et al., Reference Gillespie, Banegas, Maxwell, Chan, Darawshy, Wasil and Gewirtz2022) were often implemented in refugee camps with small (underpowered) samples, and there was little consistency in intervention content and mental health outcomes reported. While some studies reported improvements in maternal mental health, child cognitive functioning, and child psychological well-being post-intervention, these improvements were not always statistically significant.

Neighbourhood domain

Eight reviews with Neighborhood domain interventions were identified (Baxter, Tweed, Katikireddi, & Thomson, Reference Baxter, Tweed, Katikireddi and Thomson2019; Benston, Reference Benston2015; Groton, Reference Groton2013; Krahn, Caine, Chaw-Kant, & Singh, Reference Krahn, Caine, Chaw-Kant and Singh2018; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Kesten, López-López, Ijaz, McAleenan, Richards and Audrey2018; Onapa et al., Reference Onapa, Sharpley, Bitsika, McMillan, MacLure, Smith and Agnew2022; O'Donnell et al., Reference O'Donnell, Hatzikiriakidis, Savaglio, Vicary, Fleming and Skouteris2022; Thomson, Thomas, Sellstrom, & Petticrew, Reference Thomson, Thomas, Sellstrom and Petticrew2013). Examples of neighborhood determinants of mental health include urban infrastructure, neighborhood deprivation, built environment, safety and security (violence), and housing access and quality. SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy) and 11 (sustainable cities and communities) are examples of SDGs relevant to this domain. Three reviews were given a moderate or high confidence rating.

Increasing access to housing

Two reviews focusing on access to housing for people experiencing homelessness included studies conducted in North America. One (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Tweed, Katikireddi and Thomson2019) reported on four Housing First studies, defined as ‘rapid provision of permanent, non-abstinence-contingent housing’. Control conditions varied considerably and often involved intensive service access. For mental health and substance use, no clear differences were seen between individuals in Housing First and control conditions. A more recent review (Onapa et al., Reference Onapa, Sharpley, Bitsika, McMillan, MacLure, Smith and Agnew2022) included four types of housing interventions: permanent supportive, transitional, social, and community housing. Again, control conditions varied considerably and involved access to a range of services. Overall, there were no clear significant differences in mental health outcomes between groups.

Improving the physical fabric of housing

One review assessed interventions to improve the physical fabric of housing in high-income countries, mostly in socioeconomically deprived areas (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Thomas, Sellstrom and Petticrew2013). Interventions involved rehousing or retrofitting of homes, with or without neighborhood renewal, and implementing warmth and energy efficiency improvements. Overall, few statistically significant changes in mental health outcomes were reported post-intervention.

Sociocultural domain

Thirty-one reviews with Sociocultural interventions were identified (Blewitt et al., Reference Blewitt, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, Nolan, Bergmeier, Vicary, Huang and Skouteris2018, Reference Blewitt, O'Connor, Morris, May, Mousa, Bergmeier and Skouteris2021; Boncu, Costea, & Minulescu, Reference Boncu, Costea and Minulescu2017; Cantone et al., Reference Cantone, Piras, Vellante, Preti, Daníelsdóttir, D'Aloja and Bhugra2015; Casanova, Zaccaria, Rolandi, & Guaita, Reference Casanova, Zaccaria, Rolandi and Guaita2021; Cheney, Schlosser, Nash, & Glover, Reference Cheney, Schlosser, Nash and Glover2014; Choi, Kong, & Jung, Reference Choi, Kong and Jung2012; Coll-Planas et al., Reference Coll-Planas, Nyqvist, Puig, Urrútia, Solà and Monteserín2017; Cordier et al., Reference Cordier, Speyer, Mahoney, Arnesen, Heidi Mjelve and Nyborg2021; Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, Reference Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor and Schellinger2011; Fenwick-Smith, Dahlberg, & Thompson, Reference Fenwick-Smith, Dahlberg and Thompson2018; Flores et al., Reference Flores, Fuhr, Bayer, Lescano, Thorogood and Simms2018; Franck, Molyneux, & Parkinson, Reference Franck, Molyneux and Parkinson2016; Ghiga et al., Reference Ghiga, Pitchforth, Lepetit, Miani, Ali and Meads2020; Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Sklad, Elfrink, Schreurs, Bohlmeijer and Clarke2019; Guzman-Holst, Zaneva, Chessell, Creswell, & Bowes, Reference Guzman-Holst, Zaneva, Chessell, Creswell and Bowes2022; Kuosmanen, Clarke, & Barry, Reference Kuosmanen, Clarke and Barry2019; Lee, Brown, Salih, & Benoit, Reference Lee, Brown, Salih and Benoit2022; Luo, Reichow, Snyder, Harrington, & Polignano, Reference Luo, Reichow, Snyder, Harrington and Polignano2022; Murano, Sawyer, & Lipnevich, Reference Murano, Sawyer and Lipnevich2020; Nagy & Moore, Reference Nagy and Moore2017; Noone et al., Reference Noone, McSharry, Smalle, Burns, Dwan, Devane and Morrissey2020; Pollok, van Agteren, Chong, Carson-Chahhoud, & Smith, Reference Pollok, van Agteren, Chong, Carson-Chahhoud and Smith2018; Ronzi, Orton, Pope, Valtorta, & Bruce, Reference Ronzi, Orton, Pope, Valtorta and Bruce2018; Schindler et al., Reference Schindler, Kholoptseva, Oh, Yoshikawa, Duncan, Magnuson and Shonkoff2015; Siette, Cassidy, & Priebe, Reference Siette, Cassidy and Priebe2017; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Waqas, Hamdani, Suleman, Zafar, Zill and Rahman2020; Ștefan, Dănilă, & Cristescu, Reference Ștefan, Dănilă and Cristescu2022; Taylor, Oberle, Durlak, & Weissberg, Reference Taylor, Oberle, Durlak and Weissberg2017; van de Sande et al., Reference van de Sande, Fekkes, Kocken, Diekstra, Reis and Gravesteijn2019; Yang, Datu, Lin, Lau, & Li, Reference Yang, Datu, Lin, Lau and Li2019). Examples of sociocultural determinants of mental health include social capital, participation, and support, education, and Indigenous knowledge and culture. SDG 4 (quality education) is an example of a relevant SDG in this domain. Nine reviews were given a moderate or high confidence rating.

Increasing social inclusion and capital in older adults

Three reviews assessed the mental health impacts of interventions which aimed to promote social inclusion and social capital in older adults. One review reported that social support and social activity interventions were ineffective in reducing depression or anxiety in this population (Coll-Planas et al., Reference Coll-Planas, Nyqvist, Puig, Urrútia, Solà and Monteserín2017), and another reported that the use of video calls to facilitate communication between nursing home residents and their families resulted in no difference in symptoms of depression (Noone et al., Reference Noone, McSharry, Smalle, Burns, Dwan, Devane and Morrissey2020). One review reported reduced depression and anxiety scores in older people participating in intergenerational, music/singing, art and culture, and multi-activity interventions, but not information and communication technology interventions (Ronzi et al., Reference Ronzi, Orton, Pope, Valtorta and Bruce2018).

Increasing social capital and community participation

One review (Flores et al., Reference Flores, Fuhr, Bayer, Lescano, Thorogood and Simms2018) summarized interventions aiming to improve social capital and participation in community networks across a range of groups. Three studies reported reduced depression and anxiety following a community engagement and educative program, a community-based singing group, and a sociotherapy intervention. Overall, the magnitude of intervention effects was unclear.

Indigenous knowledge and culture in mental health

Two reviews summarized interventions which incorporated Indigenous knowledge and culture in mental health solutions. One review (Pollok et al., Reference Pollok, van Agteren, Chong, Carson-Chahhoud and Smith2018) included culturally adapted CBT programs. The authors reported that the evidence is currently not sufficient to conclude that culturally adapted interventions targeting depression in Indigenous people are effective. They did however note that culturally adapted programs scored highly on participant satisfaction, consequently improving treatment uptake and adherence. Another review (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Brown, Salih and Benoit2022) assessed a range of different interventions with Indigenous populations, which included Indigenous involvement in the content development or delivery. The effectiveness of these interventions was mixed; some studies reported improvements in mental health outcomes such as depressive symptoms, psychological distress, PTSD symptoms, and stress post-intervention, but some studies did not report such improvements. The involvement of Indigenous peoples and organizations in the interventions was often unclear due to varied reporting.

School-based social and emotional learning programs

Two reviews reported on the effectiveness of social and emotional learning interventions in educational settings. A review (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Reichow, Snyder, Harrington and Polignano2022) of classroom-wide social-emotional interventions for preschool children, in mostly high-income countries, reported statistically significant and meaningful effects on the reduction of challenging behavior in preschool children. Interventions with a family component or delivered by non-classroom teachers (e.g. researchers), had statistically significantly larger effect sizes. Another review (Singla et al., Reference Singla, Waqas, Hamdani, Suleman, Zafar, Zill and Rahman2020) reported on social and emotional learning and life skills programs for adolescents aged 10-to-19-years in low- and middle-income countries. These interventions reported significant reductions in symptoms of anxiety, depression, PTSD, and aggression.

School-based anti-bullying programs

One review assessed anti-bullying interventions in schools (Guzman-Holst et al., Reference Guzman-Holst, Zaneva, Chessell, Creswell and Bowes2022), and reported a very small effect in reducing overall internalizing symptoms, anxiety, and depression post-intervention. The intervention component ‘working with peers’ was associated with a significant reduction in internalizing symptoms, and using CBT techniques was associated with a significant increase. Whole-school approaches were significantly more effective than usual school practice and had a larger effect size than targeted interventions, which were not significantly more effective than usual practice.

Multiple domains

In four instances, a review could be allocated to more than one domain and was assigned to a multiple domains category (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Steare, Dedat, Pilling, McCrone, Knapp and Lloyd-Evans2022; Moledina et al., Reference Moledina, Magwood, Agbata, Hung, Saad, Thavorn and Pottie2021; Sweet & Appelbaum, Reference Sweet and Appelbaum2004; Yakubovich, Bartsch, Metheny, Gesink, & O'Campo, Reference Yakubovich, Bartsch, Metheny, Gesink and ’'Campo2022). The studies within these reviews presented interventions delivered to specific populations, but the interventions did not necessarily target multiple determinants. Two of these reviews were given a moderate or high confidence rating.

One review included housing, income assistance, and social support interventions which aimed to improve the health and well-being of persons with lived experience of homelessness (Moledina et al., Reference Moledina, Magwood, Agbata, Hung, Saad, Thavorn and Pottie2021). Most studies found no benefit of permanent supportive housing on mental health or substance use outcomes compared to control groups in this population. Mental health impacts of income assistance interventions were mixed; while rental subsidies for individuals experiencing homelessness and AIDS, and homeless families with one child, demonstrated benefits on mental-health status, the same benefits were not shown for veterans experiencing homelessness. Programs in financial empowerment and compensated work-therapy did not show significant benefits on mental health status. Peer support programs for substance use had mixed outcomes, with one study reporting harms pertaining to depression and anxiety symptoms.

Another review presented interventions for women experiencing intimate partner violence, including housing interventions and programs focusing on aspects of education, advocacy, vocational training, counseling, and financial assistance (Yakubovich et al., Reference Yakubovich, Bartsch, Metheny, Gesink and ’'Campo2022). The majority of relevant studies reported significant intervention effects. Depressive symptoms, PTSD, psychological distress, anxiety, and substance use generally showed evidence of reductions following housing interventions, particularly in the form of shelters. The magnitude of reductions in these outcomes were not reported.

Discussion

This is the largest and most comprehensive review to date of interventions targeting the social determinants of mental disorders which align with the UN SDGs. We identified several promising interventions for the prevention of mental disorders, which had a good evidence base, and for the first time highlight synergies where acting on a range of UN SDGs can be beneficial for public mental health. This review is timely, given a recent meta-analysis of over 3000 scientific studies reported that action on the UN Sustainable Development Agenda has largely been discursive, rather than transformative, to date (Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Hickmann, Sénit, Beisheim, Bernstein, Chasek and Wicke2022). This review may serve as a useful resource for academics, clinicians, policymakers, and professionals working across a variety of fields which directly and indirectly impact public mental health, making it clearer which interventions should be invested in and providing directions for future research.

Recommendations for intervention investment and future development

Based on this synthesis, recommendations for intervention investment and development can be made. In the Demographic domain, digital and brief advocacy interventions were found to be beneficial for the mental health of female IPV survivors, but future interventions should test whether targeting partners increases the effectiveness of such approaches (Emezue et al., Reference Emezue, Chase, Udmuangpia and Bloom2022). In the Economic domain, cash transfer programs (CTs) were found to offer the greatest potential benefits for mental health in low- and middle-income countries, but some conditionalities may increase stress (McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Kaiser and Bach-Mortensen2022; Wollburg et al., Reference Wollburg, Steinert, Reeves and Nye2023; Zaneva et al., Reference Zaneva, Guzman-Holst, Reeves and Bowes2022; Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Garman, Avendano-Pabon, Araya, Evans-Lacko, McDaid and Lund2021). Future research should look at implementing CTs in high-income countries and pay close attention to the impact of cash amounts and conditionalities on outcomes (Lund et al., Reference Lund, De Silva, Plagerson, Cooper, Chisholm, Das and Patel2011). In high-income countries, improved work schedules for healthcare workers (Ruotsalainen et al., Reference Ruotsalainen, Verbeek, Mariné and Serra2014), the Workplace Triple P Program for working parents (Suto et al., Reference Suto, Balogun, Dhungel, Kato and Takehara2022), and Job Clubs for unemployed individuals (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Kapur, Hawton, Richards, Metcalfe and Gunnell2017) offer mental health benefits, although may not generalize, given diverse national policies, labor markets, and welfare systems (Audhoe et al., Reference Audhoe, Hoving, Sluiter and Frings-Dresen2010). Investment in psychosocial support for vulnerable individuals following environmental events results in better mental health outcomes than not providing any support (Alzaghoul et al., Reference Alzaghoul, McKinlay and Archer2022; Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Benedetto, Harris, Boland, Christian, Hill and Clegg2021; Li et al., Reference Li, Shi, Gao, Shi, Feng, Liang and Hall2022; Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2018a, Reference Purgato, Gross, Betancourt, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon and Barbui2018b). There is a need to move away from reactive Western psychosocial approaches, to approaches which aim to prevent environmental events (e.g. climate action) or which address other social determinants (e.g. food security) in the context of disasters (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018; Shah et al., Reference Shah, Walker, Naik, Rajan, O'Hagan, Black and Stansfield2021). In the Sociocultural domain, school-based social and emotional learning (SEL) programs showed the greatest promise for improved mental health (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Reichow, Snyder, Harrington and Polignano2022; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Waqas, Hamdani, Suleman, Zafar, Zill and Rahman2020). Future SEL programs should work toward ensuring home components are incorporated, procedural fidelity is monitored, and that curricula are gender sensitive (Blewitt et al., Reference Blewitt, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, Nolan, Bergmeier, Vicary, Huang and Skouteris2018; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Reichow, Snyder, Harrington and Polignano2022; Murano et al., Reference Murano, Sawyer and Lipnevich2020; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Waqas, Hamdani, Suleman, Zafar, Zill and Rahman2020; Ștefan et al., Reference Ștefan, Dănilă and Cristescu2022; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Datu, Lin, Lau and Li2019). Few effective Neighborhood domain interventions were identified; this is consistent with a previous review of national-level interventions (Shah et al., Reference Shah, Walker, Naik, Rajan, O'Hagan, Black and Stansfield2021). Notable differences in the interventions implemented in low-, middle-, and high-income countries were observed. Interventions in high-income countries tended to be more targeted (e.g. workplace lighting interventions) compared to low- and middle-income countries where interventions were more often universal (e.g. cash transfer programs).

Challenges and potential solutions

Assessments of review quality on the AMSTAR-2 indicated most reviews were of low or critically low quality. This is possibly because the AMSTAR-2 is conceptually framed/weighted towards a hierarchy of evidence that assumes randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analytic methods should be prioritized (Shah et al., Reference Shah, Walker, Naik, Rajan, O'Hagan, Black and Stansfield2021). Rigidity around hierarchy of evidence presents a challenge when designing, implementing, and evaluating interventions focused on social determinants of mental health. Although RCTs are the ‘gold standard’ for identifying causal effects and are commonly relied upon in evidence-based policy development (Cairney, Reference Cairney2019), concerns regarding the use of RCTs consistently emerged in the studies reviewed. Withholding interventions from vulnerable individuals was seen as unethical and, at times, it was not practically or operationally feasible to conduct RCTs. While smaller-scale controlled interventions have good internal validity, they can have limited generalizability to larger contexts due to implementation challenges at scale and confounding factors (Victora, Habicht, & Bryce, Reference Victora, Habicht and Bryce2004). The assumption that internally valid RCTs can be replicated under real-world conditions may be appropriate when evaluating interventions with short and simple causal pathways (e.g. individual-level vaccine interventions), but these assumptions are often inappropriate when evaluating population-level interventions that are distal to the outcome, have complex pathways to impact, and are affected by numerous socio-ecological characteristics (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018; Shah et al., Reference Shah, Walker, Naik, Rajan, O'Hagan, Black and Stansfield2021; Victora et al., Reference Victora, Habicht and Bryce2004).

A range of study designs are required to develop evidence for social determinants interventions, and alternative quantitative methods could be utilized where social determinants are not readily amenable to randomization. For example, with the growing availability of routinely collected data (Petticrew et al., Reference Petticrew, Cummins, Ferrell, Findlay, Higgins, Hoy and Sparks2005), quasi-experimental/‘natural experiment' designs may be especially useful to assess the effects of policies related to social determinants, as well as area-level interventions like changes to built environments (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Kesten, López-López, Ijaz, McAleenan, Richards and Audrey2018). These types of research designs would be particularly useful for determinants of mental disorders in the Neighborhood domain, for which a dearth of evidence currently exists. Natural experiments have greater external validity, as they provide assessments of effectiveness rather than efficacy, but their generalizability across varying contexts must be considered and multisite evaluations are likely necessary (Petticrew et al., Reference Petticrew, Cummins, Ferrell, Findlay, Higgins, Hoy and Sparks2005). In addition to novel quantitative and practice-based methods, evidence could be triangulated with qualitative research and mixed-methods implementation science approaches to address questions of mechanisms, context, and culture, to inform the development of interventions and to assess their uptake, acceptability, and scalability (Crable, Lengnick-Hall, Stadnick, Moullin, & Aarons, Reference Crable, Lengnick-Hall, Stadnick, Moullin and Aarons2022; Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018).

The interventions reviewed almost exclusively targeted singular determinants of mental disorders and did not consider the complexity of co-occurring determinants, or the intersection of adversities, which can create cumulative stress across generations (Alegría, NeMoyer, Falgàs Bagué, Wang, & Alvarez, Reference Alegría, NeMoyer, Falgàs Bagué, Wang and Alvarez2018; Allen, Balfour, Bell, & Marmot, Reference Allen, Balfour, Bell and Marmot2014). There is a need to properly account for this in intervention design and evaluation. For example, beyond addressing individual and interpersonal dimensions of child abuse, prevention programs could benefit by addressing systemic contributors, such as cultural or organizational norms, socioeconomic, and structural inequalities (Waid et al., Reference Waid, Cho and Marsalis2022).

Despite targeting singular determinants, significant heterogeneity was noted with respect to interventions within each domain, participant groups included, outcomes measured, and duration of follow-up. While this limits the ability to comment on patterns and reflect on the strongest interventions for public mental health, it also highlights the tension between standardizing intervention designs and the importance of appropriately tailoring interventions to particular groups and contexts (Beidas et al., Reference Beidas, Dorsey, Lewis, Lyon, Powell, Purtle and Lane-Fall2022). Co-produced, interdisciplinary approaches are required to ensure greatest impact (Pérez Jolles et al., Reference Pérez Jolles, Willging, Stadnick, Crable, Lengnick-Hall, Hawkins and Aarons2022), and special attention should be paid to ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches which may widen social and mental health inequalities (Frohlich & Potvin, Reference Frohlich and Potvin2008).

Investment in research with longer follow-up periods is required to allow participants to practice and master newly acquired skills (e.g. workplace training) or adjust to new conditions (e.g. after moving house) and more accurately capture longer-term intervention impacts on mental health (Gayed et al., Reference Gayed, Milligan-Saville, Nicholas, Bryan, LaMontagne, Milner and Harvey2018; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Thomas, Sellstrom and Petticrew2013). Mental health indicators were often examined as secondary outcomes of interventions across studies, which meant that in many cases studies may have been underpowered to detect effects. Although the mental health effects of some social determinants interventions may be small, at a population-level these effects have the potential for producing a greater net benefit than large changes in smaller segments of populations (Ogilvie et al., Reference Ogilvie, Adams, Bauman, Gregg, Panter, Siegel and White2020; Zaneva et al., Reference Zaneva, Guzman-Holst, Reeves and Bowes2022). Investment is required to enable studies with larger sample sizes to ensure adequate statistical power is achieved. Intervention effectiveness may also be improved if interventions are designed with the improvement of culturally valid mental health outcomes in mind (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Brooke-Sumner, Baingana, Baron, Breuer, Chandra and Kieling2018). Cost-benefit or return-on-investment analyses should be a standard part of evaluations to demonstrate the economic benefits of prevention and to explore the cost-effectiveness of integrated interventions over siloed programming (Efevbera et al., Reference Efevbera, McCoy, Wuermli and Betancourt2018).

Despite the array of challenges presented in the available literature, we were able to make some recommendations for which interventions with a good evidence base currently warrant investment, and how alternative research designs may be considered to continue to improve the evidence base moving forward. Overall, improving major social determinants of mental disorders may ultimately be considered a political question rather than one of scientific evidence; however, calls for scientific evidence or expertise are a regular part of informing government strategies or policy-making, and political action is more likely to occur with the pressure of building scientific evidence. This has been seen in other public health examples, such as smoking and lung cancer (Berridge, Reference Berridge1999). While smoking is a public health issue which may be viewed as having a simpler causal pathway in contemporary society, the progressive generation of scientific evidence about the harmful effects of smoking eventually led to policy changes, such as the introduction of taxes on cigarettes in some countries, with major improvements in tobacco-related mortality (Nagelhout et al., Reference Nagelhout, Levy, Blackman, Currie, Clancy and Willemsen2012). In line with the precautionary principle (Kreuter, De Rosa, Howze, & Baldwin, Reference Kreuter, De Rosa, Howze and Baldwin2004), we do not believe that we should wait for perfect evidence on interventions before demanding action to improve the social determinants of mental health but rather view the process of generating scientific evidence as a progressive agent for political action. A challenge which remains is the time it takes to build this evidence and to see the benefits of these complex, intergenerational preventive interventions, against the tension of short-term funding and political cycles, where there is pressure to demonstrate more immediate success.

Strengths and limitations of the review

A strength of the review is the robust systematic methodology which prioritized higher quality evidence. Despite the broad heterogeneity of the described reviews, the synthesis of these reviews allowed us to identify key similarities and gaps across the international research, which would not be possible when considering the single reviews in isolation.

The findings from this systematic review should be interpreted with some limitations in mind. First, more recently published original research may not have been included in reviews, and a degree of overlap in the primary studies presented in the reviews is also possible. The exclusion of reviews not published in peer-reviewed journals may have omitted some evidence. This review focused on mental disorders only, but future work could explore indicators of mental wellbeing, which may be more amenable to social determinants interventions (McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Kaiser and Bach-Mortensen2022).

While our systematic review of reviews provides important leads and an overview of a complex landscape, there is an inherent lack of control over the primary research conducted and the reviews of primary research presented. Further in-depth analysis in each area is required, particularly pertaining to the opportunities and feasibility of utilizing alternative research designs to explore complex interventions, to continue building useful evidence to encourage political action.

Conclusion

Addressing the UN SDGs, which align with known social determinants of mental disorders, presents an opportunity to reduce the burden of poor mental health globally. This review demonstrates opportunities for interventions that target social determinants across demographic, economic, environmental events, neighborhood, and sociocultural domains. Interdisciplinary and novel approaches to intervention design, implementation, and evaluation are required to expand the current evidence base, encourage political action, and improve the social circumstances and mental health experienced by individuals, communities, and populations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724000333.

Author contributions

TKO, JDM, and MH conceived the study. JDM and MH were responsible for acquisition of funding. TKO developed review methods and study design with supervision from JDM. TKO led the development and registration of the review protocol, and led review design, delivery, and analysis. TKO and MTN conducted study search, screening, and selection. TKO, MTN, LM, HGJ, GC, and DA conducted data extraction and quality appraisals. TKO led the initial drafting of the manuscript, with input from JDM, MH, and CL. All authors contributed to the interpretation of findings. All authors were involved in drafting the work or revising it critically prior to submission. All authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding statement

This work and TKO were supported by the King's Together Multi and Interdisciplinary Research Scheme (Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund (grant reference: 204823/Z/16/Z)). JDM is part supported by the ESRC Centre for Society and Mental Health at King's College London (ESRC Reference: ES/S012567/1) and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London (NIHR ARC South London) at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the author[s] and not necessarily those of the ESRC, NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or King's College London. KD is supported by a National Health & Medical Research Council, Australia (Investigator Grant). The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of NHMRC. CL is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (using the UK's Official Development Assistance (ODA) Funding) and Wellcome Trust (grant number: 221940/Z/20/Z) under the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC)-Wellcome Partnership for Global Health Research through the ‘Improving adolescent mental health by reducing the impact of poverty (ALIVE)’ study. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Wellcome Trust, NIHR or the DHSC. GC is supported by an NIHR funded Academic Clinical Fellowship.

Competing interests

The authors do not report any conflicts of interest.