Soya is a product of the Asian plant Glycine max, and it has been part of human nutrition in different parts of the world for more than 2000 years. Soya-based infant formulas (SIF) are products derived from soya, which also have a long history of use around the world( Reference Ruhrah 1 ). They were used for the first time in the USA in 1909 as food alternatives for infants who had allergy or intolerance to cows' milk-based formulas (CMF). Since that report and until 1960s, these infant formulas have been products entirely derived from soya flour, with different protein availability, digestibility, fibres, phytates and protease inhibitors( Reference Hill and Stuart 2 ). The limitations of formulas based on soya flour spurred the development of SIF, in which proteins isolated from soya replaced soya flour during the 1960s. Soya protein isolate (SPI) was extracted from the flake using a slightly alkaline solution and was precipitated at the isoelectric point. The resulting isolate had a purity ≥ 90 %, a high protein digestibility and a balanced high concentration of essential amino acids( Reference Henley and Kuster 3 ).

During the 1970s, SIF were updated and fortified with l-methionine, l-carnitine and taurine. l-Methionine improved the biological quality of the protein (one of the major criticisms on soya formulas). Other criticisms on SIF are the high levels of aluminium (500–2500 μ/l v. 15–400 and 4–65 μg/l in CMF and human milk (HM)) and the presence of phytates (SIF contain approximately 1·5 % of phytates), which may impair the absorption of minerals and trace elements( 4 ). Modern SIF contain P and Ca at concentrations that are about 20 % higher than those present in CMF. These formulas are supplemented with Fe and Zn, and the protease inhibitor activity has been removed by up to 90 %. In fact, a soyabean protease inhibitor with the properties of an antitrypsin, antichymotrypsin and antielastin as heated for infant formulas removes majority of this protease inhibitor activity and renders it nutritionally irrelevant.( 4 , 5 )

SIF have been indicated for use in children with cows' milk protein allergy and post-infectious diarrhoea due to lactose intolerance and galactosaemia, for use as a vegan HM substitute, and for the treatment of common feeding problems, such as fussiness, gas and spit-up. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) supports the use of SPI-based formulas as safe and effective alternatives to provide appropriate nutrition for the normal growth and development of term infants whose nutritional needs are not being met by HM or formulas based on cows' milk( 6 ).

Another important topic of discussion is phyto-oestrogens (isoflavones) present in SIF. Commercially, SIF contain 32–47 mg/l of isoflavones, while mother's milk contains only 1–10 μg/l. The three main aglycones found in SIF are genistein, daidzein and, to a smaller extent, glycitein. Concerns have been raised about the genistein content of soya formulas because of its potential negative effects on sexual development and reproduction, neurobehavioural development, immune function and thyroid function( 7 , 8 ).

However, soya formulas and other soya-based foods contain many components, of which genistein is only one. Chen & Rogan( Reference Chen and Rogan 9 ) reported that only 3·2–5·8 % of total isoflavones in soya formulas consist of unconjugated genistein and daidzein and that amounts can vary by batch. The majority (>65 %) of isoflavones detected in soya formulas are conjugated to sugar molecules to form glycosides( Reference Setchell, Zimmer-Nechemias and Cai 10 ). The levels of isoflavones in cord blood, amniotic fluid, HM, and infant plasma and urine have been measured, providing evidence that isoflavones pass from the mother to the infant and that they are absorbed from infant formulas( Reference Chen and Rogan 9 – Reference Essex 12 ). An international group of paediatricians and statisticians decided to conduct a meticulous review of available evidence to determine whether there is solid scientific evidence that SIF are not safe for infants. Therefore, the aims of the present study were to search for and evaluate all the available publications on the safety profile of SIF in children, with emphasis on the potentially negative effects on anthropometric growth, bone health, reproductive, endocrine and immune functions, and behaviour. The present review does not include an analysis of the safety of SIF in patients with cows' milk protein allergy. That topic will be discussed in a different publication.

Materials and methods

Studies included and their characteristics

Cross-sectional, case–control, cohort studies or clinical trials were included in the present systematic review if they were carried out in newborns, infants or children aged up to 18 years, independent of country of origin, language or clinical condition. For inclusion, papers were required to (1) be published in English or Spanish, (2) include the use of any type of SIF in at least one arm and (3) include a comparison with another type of infant formula for feeding purposes and measure/compare the effects of SIF on one or more of the following parameters: weight or height changes; Ca metabolism and/or bone mineral density; phyto-oestrogen levels in blood or urine (genistein, daidzein or equol); the effects of phyto-oestrogens on reproductive or endocrine functions (thyroid parameters); the effects on cognition and/or behaviour. We also included papers that analysed the health effects of phytates and aluminium.

Search strategies

Highly sensitive evidence search strategies were employed as described by Wilczynski et al.( Reference Wilczynski and Haynes 13 ) for the identification of observational studies and by Atkins et al.( Reference Atkins, Best and Briss 14 ) for clinical trials, adding the keywords ‘(soy or soy and infant and formula) or (weight gain) or (height gain) or (hemoglobin changes) or (total and protein changes) or (albumin or globulin levels) or (zinc or calcium values) or (bone and mineral and content) or (genistein or daidzein; or equol levels) or (precocious and puberty) or (breast and bud) or (breast and tissue) or (breast and enlargement) or (thelarche or menarche) or (menstrual and cycle and length) or (pregnancy) or (abortion or miscarriage) or (ectopic and pregnancy) or (preterm and birth) or (antibodies) or (lymphocytes) or (infectious and episodes) or (thyroid) or (cancer)’. We limited the search strategy to studies conducted in human beings. Mostly as a result of research in animal models, concerns have been expressed regarding the safety of isoflavones in SIF. However, application to human populations is limited by differences in isoflavone metabolism among animal species. In fact, multiple studies have shown that there is no conclusive evidence from animals that indicates that dietary isoflavones may adversely affect the health of children. That is why we focused only on studies carried out in human subjects. The search was carried out electronically and manually in the following databases: PubMed (1909 to July 2013); Embase (1988 to May 2013); LILACS (1990 to May 2011); ARTEMISA (13th edition to December 2012); Cochrane controlled trials register; Bandolier; DARE.

Evidence quality evaluation

We used the standardised methods described by the Cochrane Collaboration for preparing the protocol, applying the criteria of inclusion, evaluating the quality of publications and extracting information. The quality of publications was determined using the GRADE system( Reference Atkins, Best and Briss 14 ). The GRADE approach specifies four levels of quality of the evidence: HIGH (randomised trials or double-upgraded observational studies); MODERATE (downgraded randomised trials or upgraded observational studies); LOW (double-downgraded randomised trials or observational studies); VERY LOW (triple-downgraded randomised trials or downgraded observational studies or case series/case reports)( Reference Atkins, Best and Briss 14 ). Using a double-blind and independent strategy, two authors extracted and evaluated the quality of relevant information in formats designed a priori for this purpose. Any disagreement in data collated was resolved by discussion and analysis of the information.

Synthesis and analysis of information

According to the GRADE system( Reference Atkins, Best and Briss 14 ), evidence obtained is presented in tables that report limitations in design, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, summary of findings and recommendations. The effects of soya on growth and development, reproductive and endocrinological functions, and immunity were meta-analysed using a Mantel–Haenszel fixed-effects model, and they are presented graphically by a forest plot. For all the estimates, a CI of 95 % was calculated. A heterogeneity test was carried out in all cases using the I 2 test, with a significant value of P< 0·05. In the case of suspected bias of publication, a funnel plot is presented. A sensitivity analysis was carried out, where necessary.

Results

Description and quality of studies

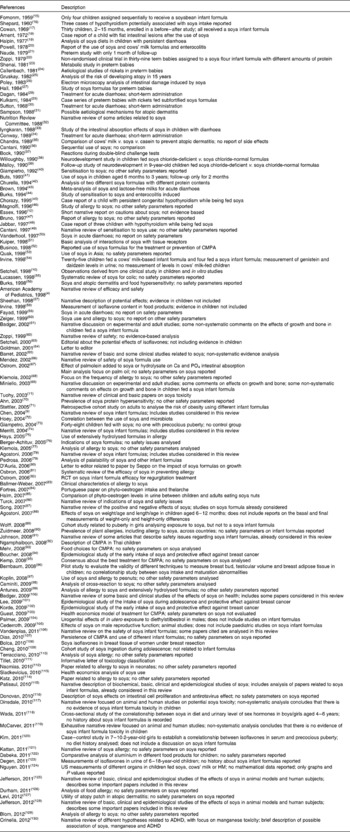

The initial search strategy yielded 156 potential studies( 4 , Reference Chen and Rogan 9 – Reference Essex 12 , Reference Fomon 15 – Reference Messina and Redmond 165 ) to be included. Upon careful review of the abstracts of each article, 121( 4 , Reference Chen and Rogan 9 – Reference Essex 12 , Reference Fomon 15 – Reference Crinella 130 ) were eliminated (Table 1), leaving a total of thirty-five articles for further analysis( Reference Kay, Daeschner and Desmond 131 – Reference Messina and Redmond 165 ). The articles were eliminated because they covered topics not related to our safety analysis, were narrative reviews of the evidence, lacked sufficient congruence between what was described in the objectives and what was reported in the analysis, and/or did not contain sufficient extractable information to contribute to the goals of the present review.

Table 1 Studies excluded from the review

CMPA, cows' milk protein allergy; RCT, randomised controlled trial; HM, human milk; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Quantitative synthesis of results

Growth and development

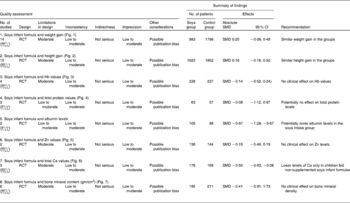

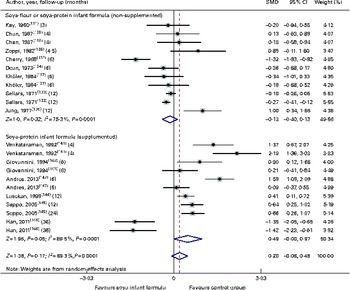

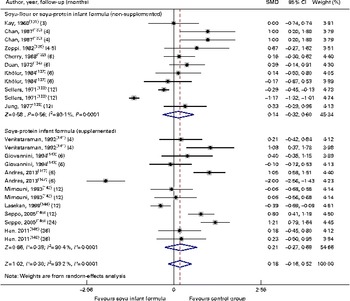

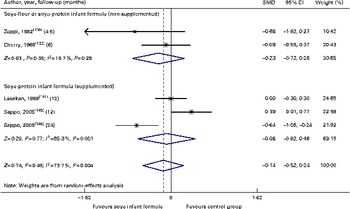

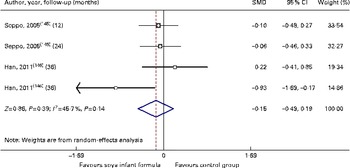

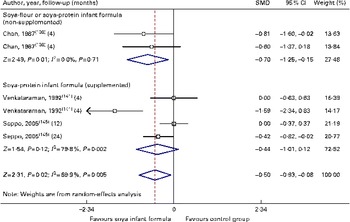

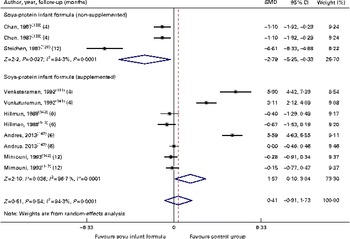

Through the present systematic review, we identified fourteen randomised controlled trials( Reference Kay, Daeschner and Desmond 131 – Reference Chan, Leeper and Boo 138 , Reference Venkataraman, Luhar and Neylan 141 , Reference Giovannini, Agostoni and Fiocchi 143 – Reference Andres, Casey and Cleves 147 ), which led us to identify the nutritional equivalence of SIF compared with that of HM and CMF regarding weight gain (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0·13, 95 % CI − 0·15, 0·41, P= NS) and length gain (SMD 0·24, 95 % CI − 0·10, 0·57, P= NS) during the first year of life. At the same time, through this evidence analysis, we found no effects of these formulas on the levels of Hb (SMD 0·14, 95 % CI − 0·52, 0·24, P= NS), total protein (SMD − 0·08, 95 % CI − 1·12, 0·97, P= NS) and Zn (SMD 0·13, 95 % CI − 0·15, 0·41, P= NS). The analysis of total Ca levels led us to establish a negative effect of old soya formulas (non-supplemented) on this mineral (SMD − 0·50, 95 % CI − 0·93, 0·08, P 0·01). This effect disappeared with the use of improved and supplemented SIF (SMD − 0·44, 95 % CI − 1·01, 0·12, P= NS). Moreover, six randomised controlled trials( Reference Chan, Leeper and Boo 138 – Reference Mimouni, Campaigne and Neylan 142 , Reference Andres, Casey and Cleves 147 ) allowed us to establish a safe profile for modern supplemented formulas with regard to bone mineral density (SMD − 0·12, 95 % CI − 1·46, 1·22, P= NS; Table 2; Figs. 1–7).

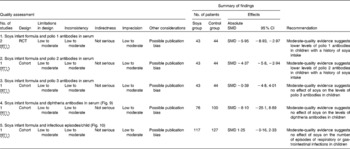

Table 2 Evidence from studies included in the review (weight, length, bone health and other nutritional parameters) (Standardised mean difference (SMD) values and 95 % confidence intervals)

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Fig. 1 Effect of soya infant formula on weight gain. SMD, standardised mean difference. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Fig. 2 Effect of soya infant formula on height gain. SMD, standardised mean difference. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Fig. 3 Effect of soya infant formula on Hb values. SMD, standardised mean difference. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Fig. 4 Effect of soya infant formula on serum total proteins. SMD, standardised mean difference. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Fig. 5 Effect of soya infant formula on serum zinc values. SMD, standardised mean difference. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Fig. 6 Effect of soya infant formula on total calcium values. SMD, standardised mean difference. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Fig. 7 Effect of soya infant formula on bone mineral content (gm/cm2). SMD, standardised mean difference. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

With regard to the potential negative effects of SIF on neurodevelopment, a study with an acceptable quality of evidence was conducted in 9- to 10-year-old children who were fed either SIF or HM during their first year of life. After adjusting for covariates, including ingestion of a chloride-deficient SIF, the authors did not find differences in intelligence quotient, behavioural problems, learning impairment or emotional problems( Reference Malloy and Berendes 148 ). Another study was conducted in 1999 among adults aged 20–34 years, who, as infants, participated in controlled feeding studies from 1965 to 1978. The percentage of men or women who achieved some level of college or trade school education, whether fed SIF or CMF, did not differ( Reference Strom, Shinnar and Ziegler 149 ). A more recently published prospective cohort study compared the developmental status (i.e. mental, motor and language) of breast-fed (HM), CMF-fed and SIF-fed infants during the first year of life. A total of 391 healthy infants were assessed longitudinally at ages 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Development was evaluated using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development and the Preschool Language Scale-3. Mixed-effects models were used while adjusting for socio-economic status, mother's age and intelligence quotient, gestational age, sex, birth weight, head circumference, race, age and diet history. No differences were found between the CMF-fed and SIF-fed infants. The HM-fed babies had a small benefit in cognitive development compared with the formula-fed infants( Reference Andres, Cleves and Bellando 150 ).

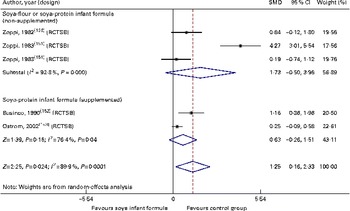

With regard to immune function and the risk of respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, we identified two randomised controlled trials( Reference Zoppi, Gasparini and Mantovanelli 151 , Reference Ostrom, Cordle and Schaller 153 , Reference Cordle, Winship and Schaller 154 ) and one cohort study( Reference Businco, Bruno and Grandolfo 152 ) with a low-to-moderate quality of evidence of similar behaviour between HM-fed, CMF-fed and SIF-fed children in relation to the percentage of B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes or natural killer cells, levels of IgA, IgG and IgM, and titration of antibodies against polio virus (SMD − 0·39, 95 % CI − 4·8, 4·01), diphtheria (SMD − 8·10, 95 % CI − 25·1, 8·89) or Haemophilus influenzae. We also found that the number of episodes/child of respiratory infections or acute diarrhoea was similar between the groups (SMD 1·25, 95 % CI − 0·16, 2·33; Table 3; Figs. 8–10).

Table 3 Evidence from studies included in the review (immunity and infection risk) (Standardised mean difference (SMD) values and 95 % confidence intervals)

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Fig. 8 Effect of soya infant formula on polio antibodies. SMD, standardised mean difference; RCTSB, randomised controlled trial, single blind. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Fig. 9 Effect of soya infant formula on diphtheria antibodies. SMD, standardised mean difference; RCTSB, randomised controlled trial, single blind. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Fig. 10 Effect of soya infant formula on infectious episodes/child. SMD, standardised mean difference; RCTSB, randomised controlled trial, single blind. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Phytate and aluminium toxicity

It is known that phytates can interfere with the intestinal absorption of Zn, Ca, Fe and P. None of the studies that we reviewed showed any negative impact of the content of phytates in SIF on anthropometric growth, Hb levels, and Ca and Zn serum levels in SIF-fed, CMF-fed children or breast-fed infants( Reference Cherry, Cooper and Stewart 132 , Reference Zoppi, Gerosa and Pezzini 136 – Reference Chan, Leeper and Boo 138 , Reference Venkataraman, Luhar and Neylan 141 , Reference Lasekan, Ostrom and Jacobs 144 – Reference Han, Yon and Han 146 ) (Figs. 1–7).

As has been described above, SIF contain higher levels of aluminium than CMF and HM. However, daily aluminium intake does not exceed 1 mg/kg, which is considered to be a tolerable level by the FAO/WHO( Reference Agostoni, Axelsson and Goulet 78 ). Before the present systematic review, no published evidence has shown a negative health effect of aluminium in full-term infants fed modern SIF. In 2008, the AAP concluded that aluminium in SIF is not a safety issue, except when fed to preterm infants or infants with renal failure( Reference Bhatia and Greer 155 ).

Reproductive and endocrine functions

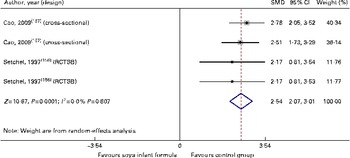

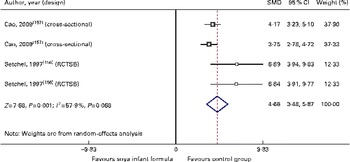

We identified one randomised controlled trial and one cross-sectional study that demonstrated with a very low quality of evidence that there is an association of SIF intake with higher serum and urine levels of genistein (SMD 2·54, 95 % CI 2·07, 3·01, P 0·0001) and daidzein (SMD 4·68, 95 % CI 3·48, 5·87, P 0·0001) v. other feedings, but with similar equol levels (SMD 0·24, 95 % CI − 9·34, 9·38, P= NS). These authors did not find significant correlations between the concentrations of isoflavones and the levels of certain hormones in children fed soya formulas( Reference Setchell, Zimmer-Nechemias and Cai 156 , Reference Cao, Calafat and Doerge 157 ). Despite convincing evidence of relatively high exposures, whether the isoflavones in SIF are biologically active in infants is an open question. If genistein, daidzein and equol are all oestrogenic in cell receptors and animals, the question appears to be primarily one of dose( Reference Cao, Calafat and Doerge 157 ). It is not conclusive what levels are biologically active and can produce organic effects. Importantly, some authors demonstrated that most of the phyto-oestrogens present in the plasma of SIF-fed infants are in a conjugated form and are therefore unable to exert hormonal effects. Our analysis of clinical evidence also produced inconclusive results( Reference Hugget, Pridmore and Malnoe 158 ) (Table 4; Figs. 11 and 12).

Table 4 Evidence from studies included in the review (reproductive and endocrine functions). (Odds ratios, risk ratios (RR) or standardised mean difference (SMD), weighted mean difference (WMD) values and 95 % confidence intervals)

Fig. 11 Effect of soya infant formula on genistein levels in serum. SMD, standardised mean difference; RCTSB, randomised controlled trial, single blind. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

Fig. 12 Effect of soya infant formula on daidzein levels in serum. SMD, standardised mean difference; RCTSB, randomised controlled trial, single blind. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

From a clinical point of view, we identified two cohort studies( Reference Strom, Shinnar and Ziegler 149 , Reference Ostrom, Cordle and Schaller 153 ) with a moderate quality of evidence of marginal unfavourable effects of SIF on early menarche (SMD − 0·36, 95 % CI − 0·69, − 0·02, P 0·04) and two studies with a very low quality of evidence (one cross-sectional study and one case–control study) where SIF seemed to be a risk factor for the presence of breast tissue during the second year of life (OR 2·44, 95 % CI 1·11, 5·39, P 0·01)( Reference Zung, Glaser and Kerem 160 , Reference Lambertina, Freni-Titulaer and Cordero 161 ). Additionally, in one of the cohort studies( Reference Strom, Shinnar and Ziegler 149 ), the authors identified an association of SIF intake with 9 h (95 % CI 1·5, 16 h) of more menstrual bleeding and more discomfort during menstrual periods (risk ratio 1·77, 95 % CI 1·04, 3·0, P 0·001). In other words, this study found only subtle effects including slight increases in the duration of women's menstrual cycles and the level of discomfort during menstruation. However, this study showed no statistically significant differences between groups in either women or men for more than thirty outcomes (e.g. precocious puberty, early thelarche, modification of cycle length, duration of menstrual bleeding, irregular menstrual periods, heavy menstrual flow, missed menstrual periods, spotting in the middle of a menstrual period, breast tenderness, frequency of pregnancies, and miscarriages or preterm deliveries) (Table 4; Fig. 13).

Fig. 13 Effect of soya infant formula on age of menarche. SMD, standardised mean difference. (A colour version of this figure can be found online at http://www.journals.cambridge.org/bjn).

In 2010, a report about the possible association between uterine fibroids and SIF intake was published. In this cohort study with a low-to-moderate quality of evidence, the authors identified a risk ratio of 1·25, but with a CI of 0·97–1·61, associated with a non-significant P value( Reference D'Aloisio, Baird and DeRoo 162 ). With regard to SIF intake and potential association with endocrine dysfunction, interestingly, we found that most of these publications were published as case reports( Reference Brown, Peerson and Fontaine 43 , Reference Conrad, Chiu and Silverman 163 , Reference Mousavi, Tavakoli and Mardan 164 ). Messina et al. ( Reference Messina and Redmond 165 ) reported no association between SIF intake and thyroid function disturbances in healthy infants with euthyroidism. These investigators identified fourteen trials in which the effects of soya foods or isoflavones on at least one measure of thyroid function were evaluated in healthy subjects: eight included only women; four involved only men; two included both men and women. With only one exception, either no effects or only very limited changes were observed in these trials. Thus together, the findings provide little evidence that in euthyroid, iodine-replete subjects, soya foods or isoflavones adversely affect thyroid function( Reference Messina and Redmond 165 ).

Discussion

Soya has been used as food throughout the world for thousands of years. Ruhräh( Reference Ruhrah 1 ) published the first report on the use of a soyabean-based formula for infants in 1909. Early SIF contained soya flour, a constituent with a poorer protein digestibility and a reduced protein content when compared with the SPI used in modern SIF. SPI replaced soya flour in infant formulas during the early 1960s. In the 1970s, methionine, iodine, carnitine, taurine, choline and inositol were added to standard SIF. Modern SIF meet the AAP recommendations and the Infant Formula Act (1980 and subsequent amendments in 1986) requirements for term infants( Reference Ruhrah 1 – 4 ).

Approximately 25 % of infants in the USA are fed SIF at some point in their first year of life (AAP, 2008)( Reference Bhatia and Greer 155 ). Recently, some findings generated in animal models or human observations have challenged the use of these formulas in infants and children because of concerns about potential negative effects on growth, bone health, immunity, cognition, and reproductive or endocrine functions( Reference Merritt and Jenks 74 , Reference Vandenplas, De Greef and Devreker 106 ). The first review about soya was a narrative review published in 1988 that focused on growth and bone mineralisation. It was a result of concerns regarding adequate bone mineralisation when rickets was observed in very-low-birth-weight infants receiving soya-based feedings. This review concluded that children fed a soya isolate formula (old composition) had a pattern of growth similar to that of children fed a CMF and that infants fed a soya isolated formula had significantly lower bone mineral content and bone width at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months of age than those fed CMF, but that their values were similar to those of previously studied infants fed HM with vitamin D supplementation( 32 ). After the publication of this paper, at least eighteen additional narrative reviews on different aspects of safety and/or efficacy of SIF were published, most of them demonstrating a safety profile for use in children( 4 , Reference Chen and Rogan 9 , Reference Cantani and Lucenti 49 , Reference Zoppi and Guandalini 62 , Reference Mendez, Anthony and Arab 66 , Reference Miniello, Morol and Tarantino 69 , Reference Merritt and Jenks 74 , Reference Agostoni, Axelsson and Goulet 78 , Reference Turck 86 , Reference Song, Chun and Hwang 87 , Reference Johnson, Loomis and Flake 91 , Reference Badger, Gilchrist and Terry Pivik 100 , Reference Vandenplas, De Greef and Devreker 106 , Reference Dinsdale and Ward 117 , Reference Kattan, Cocco and Järvinen 121 , Reference Jefferson and Williams 125 , Reference Jefferson, Patisaul and Williams 128 , Reference Crinella 130 ). In addition to these publications, only three systematic reviews with a meta-analysis were published about the efficacy of soya as an adjuvant in acute diarrhoea, infantile colic or cows' milk protein allergy prevention. In these publications, Brown et al. ( Reference Brown, Peerson and Fontaine 43 ) assessed the effects of continued feeding of non-HM or formulas to infants during acute diarrhoea on their treatment failure rates, stool frequency and amount, diarrhoeal duration and body-weight change. They concluded that the vast majority of young children with acute diarrhoea can be successfully managed with continued feeding of undiluted non-HM. Lucassen et al. ( Reference Lucassen, Assendelft and Gubbels 55 ) concluded that in infants with infantile colic, the effectiveness of substitution with soya formula milks is unclear when only trials of good methodological quality are considered. Finally, Osborn & Sinn( Reference Ostrom, Jacobs and Merritt 82 ) concluded that soya formula feeding cannot be recommended for the prevention of allergy or food intolerance in infants at a high risk of allergy or food intolerance.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review with a meta-analysis published with the focus mainly on SIF and safety in infants and children. It has the advantage of covering evidence analysis from 1909 to July 2013 (104 years), including papers published on SIF, non-enriched SIF and supplemented/enriched SIF. This extensive analysis objectively showed that SIF intake in normal full-term infants – even during the most rapid phase of growth – is associated with normal anthropometric growth, adequate protein status, bone mineralisation and normal immune development. The importance of the meta-analysis reported herein is that data demonstrate the negative effects of the ‘old/unsupplemented soya formulas’ on Ca metabolism and bone mineral content. For example, Chan et al. ( Reference Chan, Leeper and Boo 138 ) studied the mineral metabolism in healthy term infants fed the old soya formula containing different sources of carbohydrates. Exclusively breast-fed infants served as controls. These investigators found that at 2 and 4 months of age, the breast-fed infants had higher bone mineral content and bone density. On the contrary, more recent studies using modern/supplemented SIF have shown growth patterns, Ca levels, bone mineral content, serum Hb levels, total protein levels, immune factors, and upper respiratory or diarrhoeic infection risk similar to those found with other types of feedings.

Few studies have evaluated the impact of SIF on neurodevelopment. For example, a study carried out by Malloy & Berendes( Reference Malloy and Berendes 148 ), in school-aged children who were fed either SIF or HM during their first year of life, showed no differences in intelligence quotient, behavioural problems, learning impairment or emotional problems. Strom et al. ( Reference Strom, Shinnar and Ziegler 149 ) conducted a study among adults aged 20–34 years who, as infants, participated in controlled feeding studies. Results indicated no differences in men or women with regard to the achievements of the level of college or trade school education, whether they were fed SIF or CMF. Andres et al. ( Reference Andres, Cleves and Bellando 150 ), in a more recent study in healthy infants, assessed the Bayley Scales of Infant Development and the Preschool Language Scale-3 during the first year of life. No differences were found between the CMF-fed and SIF-fed infants. We are aware of the debate about differences in behaviour (mental, psychomotor and language) in breast-fed infants and formula-fed infants, which are not necessarily related only to the type of feedings.

SPI contains 1–2 % of phytates, which may impair the absorption of minerals and trace elements. Modern SIF contain higher levels of micronutrients (Ca, Zn, Fe, etc.) when compared with CMF or HM. We found that feeding SIF to young infants did not result in any negative impact on the levels of Hb, Zn, Ca and overall growth (Figs. 1–3 5). Similarly, we also found that SIF contain significantly higher levels of aluminium than CMF and HM (SIF 500–2500 μg/l, CMF 15–400 μg/l and HM 4–65 μg/l). This systematic review did not find any evidence of a negative health effect of this metal in children. SIF should not be fed to preterm infants or infants with renal failure. Studies have concluded that in term infants with normal renal function, there is no risk of aluminium toxicity from SIF.

Finally, it is known that phyto-oestrogens represent a broad group of plant-derived compounds of non-steroidal structure that are abundant within the plant kingdom, including soya, and have a weak oestrogenic activity. Minimum data are available on the potential effects of exposure to phyto-oestrogens in young children on later sexual and reproductive development. SIF-fed infants may have higher serum and urine levels of genistein and daidzein. As has been mentioned earlier, it seems that most of the phyto-oestrogens present in the plasma of SIF-fed infants are in a conjugated form and are therefore unable to exert hormonal effects( Reference Hugget, Pridmore and Malnoe 158 ). The exhaustive analysis that we conducted in the present systematic review produced inconclusive results. We identified two cohort studies with a moderate quality of evidence of marginal adverse effects of SIF on early menarche. Furthermore, two other studies with a very low quality of evidence (one cross-sectional study and one case–control study) showed that SIF would be a risk factor for the presence of breast tissue during the second year of life. Additionally, one cohort study identified an association of SIF intake with a significant increase in the duration of women's menstrual cycles and more discomfort during menstrual periods. However, the same study did not show any statistical difference between the groups for more than thirty additional outcomes, such as presence of puberty, early thelarche, modification of cycle length, severity of menstrual flow, irregular menstrual periods, heavy menstrual flow, missed menstrual periods, spotting in the middle of a menstrual period, breast tenderness, frequency of pregnancies, and miscarriages or preterm deliveries.

This evidence analysis led us to establish that there is no significant effect of soya on important reproductive functions in human beings. The AAP has emphasised that literature reviews and clinical studies of infants fed SIF raise no clinical concerns with respect to nutritional adequacy, sexual development, thyroid disease, immune function or neurodevelopment. Additional studies confirm that SIF do not interfere with normal immune responses. The US Food and Drug Administration has also approved these formulas to be safe for use in infants.

Acknowledgements

The present study did not receive funding from any agency.

Y. V. is a consultant for United Pharmaceuticals and Biocodex. P. A. was a former employee of Abbott Nutrition (now retired). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.