There is growing consensus that cognitive impairment is a key feature of bipolar disorder (BD), visible even before the first manifestation of the disease and in both acute and remitted phases (Bora et al., Reference Bora, Yücel and Pantelis2010a; Bora and Pantelis, Reference Bora and Pantelis2015). Cognitive deficits of bipolar patients primarily affect long-term verbal and visual memory skills, working memory, attention and psychomotor speed, executive functions and language (Kurtz and Gerraty, Reference Kurtz and Gerraty2009; Baune et al., Reference Baune, Li and Beblo2013). Most importantly, these deficits slow down the recovery and worsen educational and occupational attainment (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Thompson, Gallagher, Goswami, Young, Ferrier and Moore2006; Baune et al., Reference Baune, Li and Beblo2013), resulting in poorer psychosocial functioning and lower quality of life for the patients (Baune et al., Reference Baune, Li and Beblo2013). Current evidence highlights the need to systematically implement neuropsychological assessment in the clinical management of BD as an essential component for planning tailored interventions. Consistently, increasing efforts have been made to develop standardised and validated instruments for assessing cognition in BD, although a gold standard tool has not been established yet(Bakkour et al., Reference Bakkour, Samp, Akhras, El Hammi, Soussi, Zahra, Duru, Kooli and Toumi2014).

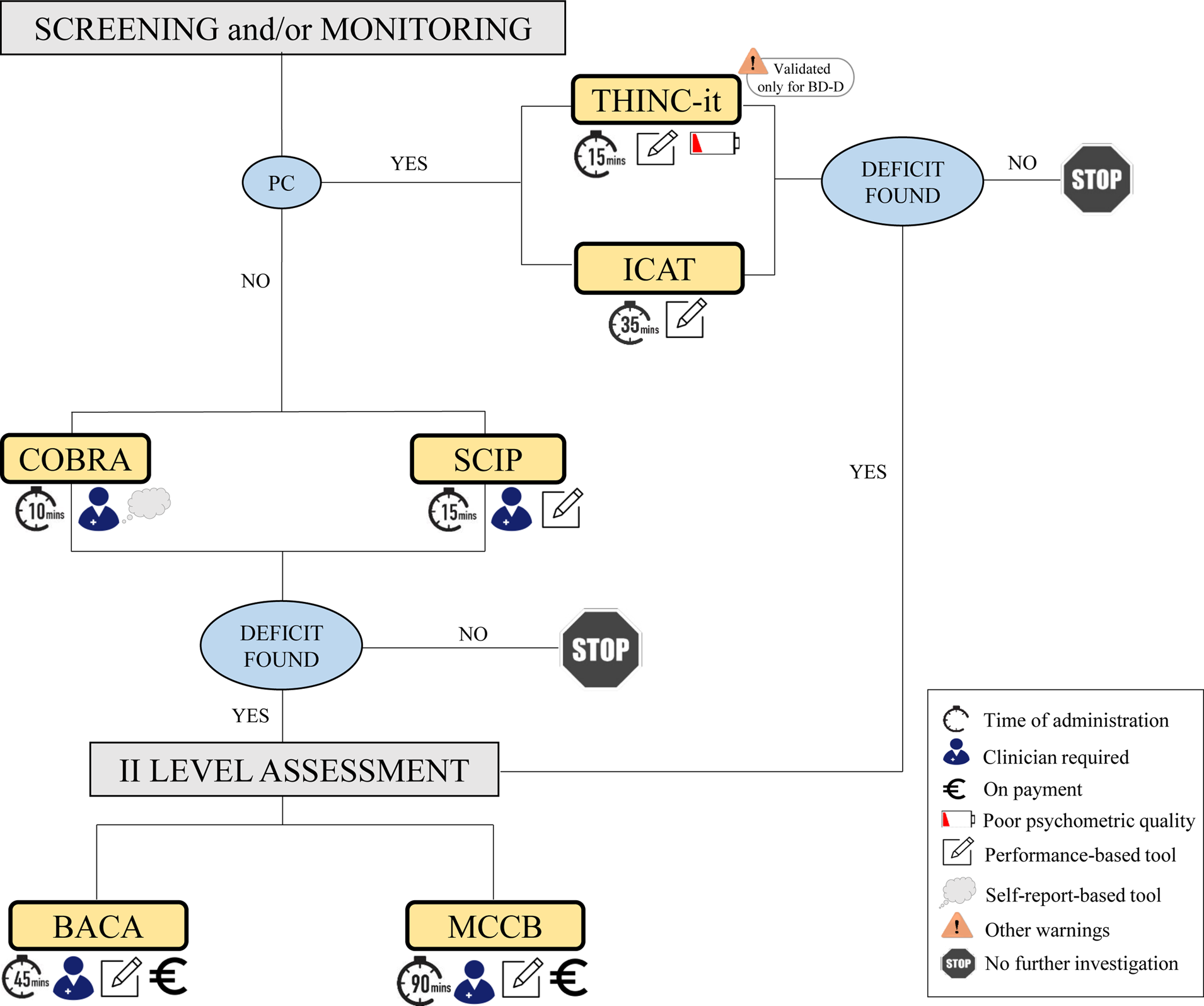

In this commentary, we critically appraised the strengths and limitations of the tools most commonly used to assess cognition in BD, both for screening purposes or to detect cognitive impairment Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. A diagram to help healthcare professionals to make the best use of tools commonly used to assess cognition in BD.

In 2018 the task force targeting cognition of the International Society for Bipolar Disorder (ISBD) published consensus-based recommendations on how to assess and manage cognitive impairment in BD (Miskowiak et al., Reference Miskowiak, Burdick, Martinez-Aran, Bonnin, Bowie, Carvalho, Gallagher, Lafer, López-Jaramillo and Sumiyoshi2018). The key recommendations were that mental health professionals formally screen cognition of bipolar patients whenever possible, by means of brief, cost-effective and easy-to-administer tools, and refer patients for extensive neuropsychological evaluation when clinically required. Specifically, the task force indicated the Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment (COBRA) and the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP) as the most feasible tools for the screening of subjective and objective cognition, respectively (Miskowiak et al., Reference Miskowiak, Burdick, Martinez-Aran, Bonnin, Bowie, Carvalho, Gallagher, Lafer, López-Jaramillo and Sumiyoshi2018). Both instruments are free of charge, brief, and do not require specific training for their administration.

The COBRA is a self-report rating scale specifically developed to test subjective cognition in BD. The instrument has high practical utility but has shown only small-to-moderate sensitivity and specificity for detecting objective cognitive impairment (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Støttrup, Nayberg, Knorr, Ullum, Purdon, Kessing and Miskowiak2015). Therefore, its use is recommended only in combination with other screeners for objective cognition (Miskowiak et al., Reference Miskowiak, Burdick, Martinez-Aran, Bonnin, Bowie, Carvalho, Gallagher, Lafer, López-Jaramillo and Sumiyoshi2018).

The SCIP is the pencil-and-paper tool most commonly used for screening objective cognition in psychiatric disorders (Guilera et al., Reference Guilera, Pino, Gómez-Benito, Rojo, Vieta, Tabarés-Seisdedos, Segarra, Martínez-Arán, Franco and Cuesta2009; Rojo et al., Reference Rojo, Pino, Guilera, Gómez-Benito, Purdon, Crespo-Facorro, Cuesta, Franco, Martínez-Arán and Segarra2010; Schmid et al., Reference Schmid, Czekaj, Frick, Steinert, Purdon and Uhlmann2021). The test has three parallel versions making it suitable for monitoring performance over time. The SCIP has been validated in BD, showing good sensitivity and specificity for detecting objective cognitive impairment (Guilera et al., Reference Guilera, Pino, Gómez-Benito, Rojo, Vieta, Tabarés-Seisdedos, Segarra, Martínez-Arán, Franco and Cuesta2009; Rojo et al., Reference Rojo, Pino, Guilera, Gómez-Benito, Purdon, Crespo-Facorro, Cuesta, Franco, Martínez-Arán and Segarra2010; Cuesta et al., Reference Cuesta, Pino, Guilera, Rojo, Gómez-Benito, Purdon, Franco, Martínez-Arán, Segarra and Tabarés-Seisdedos2011; Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Støttrup, Nayberg, Knorr, Ullum, Purdon, Kessing and Miskowiak2015). However, for this tool (as for other prospective cognitive screening tests), there is still a lack of normative data to determine clinically significant change over time at the individual level (Purdon and Psych, Reference Purdon and Psych2005).

A modified web-based version of the SCIP was developed in 2019, i.e. the Internet-Based Cognitive Assessment Tool (ICAT) (Hafiz et al., Reference Hafiz, Miskowiak, Kessing, Jespersen, Obenhausen, Gulyas, Żukowska and Bardram2019; Miskowiak et al., Reference Miskowiak, Jespersen, Obenhausen, Hafiz, Hestbæk, Gulyas, Kessing and Bardram2021). The ICAT is a patient-administered test that allows the screening of objective cognitive deficits online, using gold-standard, performance-based cognitive tasks. The ICAT has shown good sensitivity to cognitive impairment of bipolar patients and high concurrent validity with the SCIP (Miskowiak et al., Reference Miskowiak, Jespersen, Obenhausen, Hafiz, Hestbæk, Gulyas, Kessing and Bardram2021). Overall, ICAT allows assessment and monitoring of patients' cognition at a much larger scale and at a reduced cost than paper-and-pencil tests. Nonetheless, the ability to operate computers/tablets independently and the presence of an internet connection are essential prerequisites for using this instrument.

Another web-based, patient-administered cognitive screening tool that can be potentially applied to bipolar patients is the THINC-IT. This test was released prior to ICAT but was originally designed for patients with unipolar depression (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Best, Bowie, Carmona, Cha, Lee, Subramaniapillai, Mansur, Barry and Baune2017). THINC-it employs gamified cognitive tasks to engage patients in taking the tests. Similar to ICAT, THINC-IT is free of charge, brief, and user-friendly; however, it lacks an assessment of verbal learning and memory, which (ideally) should always be present in screening tools for BD since impairments in this domain represent a core feature of the disorder that is common also during remitted states (Arts et al., Reference Arts, Jabben, Krabbendam and Van Os2008; Bora et al., Reference Bora, Yücel and Pantelis2010b) and contributes to poor occupational and daily functioning (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Thompson, Gallagher, Goswami, Young, Ferrier and Moore2006; Baune et al., Reference Baune, Li and Beblo2013). Of note, THIC-IT was tested on patients with BD-II only (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhu, Lai, Liu, Ng, Chen, Qian, Du, Hu and Chen2020). Therefore, further studies including both BD-I and BD-II are needed to verify the suitability and sensitivity of this battery for cognitive assessment in BD.

Overall, cognitive screeners for use in BD take little time to administer, are easy to use and cost-effective and appear feasible in the clinical management of BD. However, they do not measure real-life functions and cannot replace a thorough neuropsychological evaluation (Miskowiak et al., Reference Miskowiak, Burdick, Martinez-Aran, Bonnin, Bowie, Carvalho, Gallagher, Lafer, López-Jaramillo and Sumiyoshi2018).

As for comprehensive neuropsychological assessments, the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) and the Brief Assessment of Cognition In Affective Disorders (BAC-A) are among the most commonly used tools with bipolar patients (Yatham et al., Reference Yatham, Torres, Malhi, Frangou, Glahn, Bearden, Burdick, Martínez-Arán, Dittmann and Goldberg2010; Van Rheenen and Rossell, Reference Van Rheenen and Rossell2014).

The MCCB was developed originally for schizophrenia (Nuechterlein et al., Reference Nuechterlein, Green, Kern, Baade, Barch, Cohen, Essock, Fenton, Frese, Frederick and Gold2008). Then, the cognition task force of the ISBD endorsed the applicability and clinical utility of most MCCB subtests for use in BD, further recommending the inclusion of more complex measures of verbal learning or executive function (Yatham et al., Reference Yatham, Torres, Malhi, Frangou, Glahn, Bearden, Burdick, Martínez-Arán, Dittmann and Goldberg2010). Preliminary evidence has shown good sensitivity of the MCCB in distinguishing between the cognitive functioning of bipolar and control groups and a need for a more thorough evaluation of specific domains as suggested by the ISBD (Van Rheenen and Rossell, Reference Van Rheenen and Rossell2014).

The BAC-A has been designed specifically for use in affective disorders (Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Fox, Davis, Kennel, Walker, Burdick and Harvey2014). The battery includes eight subtests measuring both non-affective and affective cognition. Moreover, it is suitable for test-retest evaluations as the verbal tests include alternative forms. Recent studies have demonstrated that the BAC-A is sensitive to the cognitive impairments of patients with BD in both affective and non-affective cognitive domains and has good test-retest reliability (Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Fox, Davis, Kennel, Walker, Burdick and Harvey2014; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Keefe, Sanches, Suchting, Green and Soares2015; Barbosa et al., Reference Barbosa, Ferreira, Rocha, Mol, da Mata Chiaccjio Leite, Bauer and Teixeira2018; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Wang, Lee, Hung, Huang, Lee and Lee2018; Rossetti et al., Reference Rossetti, Perlini, Abbiati, Bonivento, Caletti, Fanelli, Lanfredi, Lazzaretti, Pedrini, Piccin, Porcelli, Sala, Serretti, Bellani and Brambilla2022).

Overall, evidence suggests that both the MCCB and the BAC-A have proved sensitive to the cognitive impairment of bipolar patients and may be used for diagnostic purposes. However, these tools are expensive, time-consuming and require extensive training for their administration. Such factors limit their applicability in clinical practice.

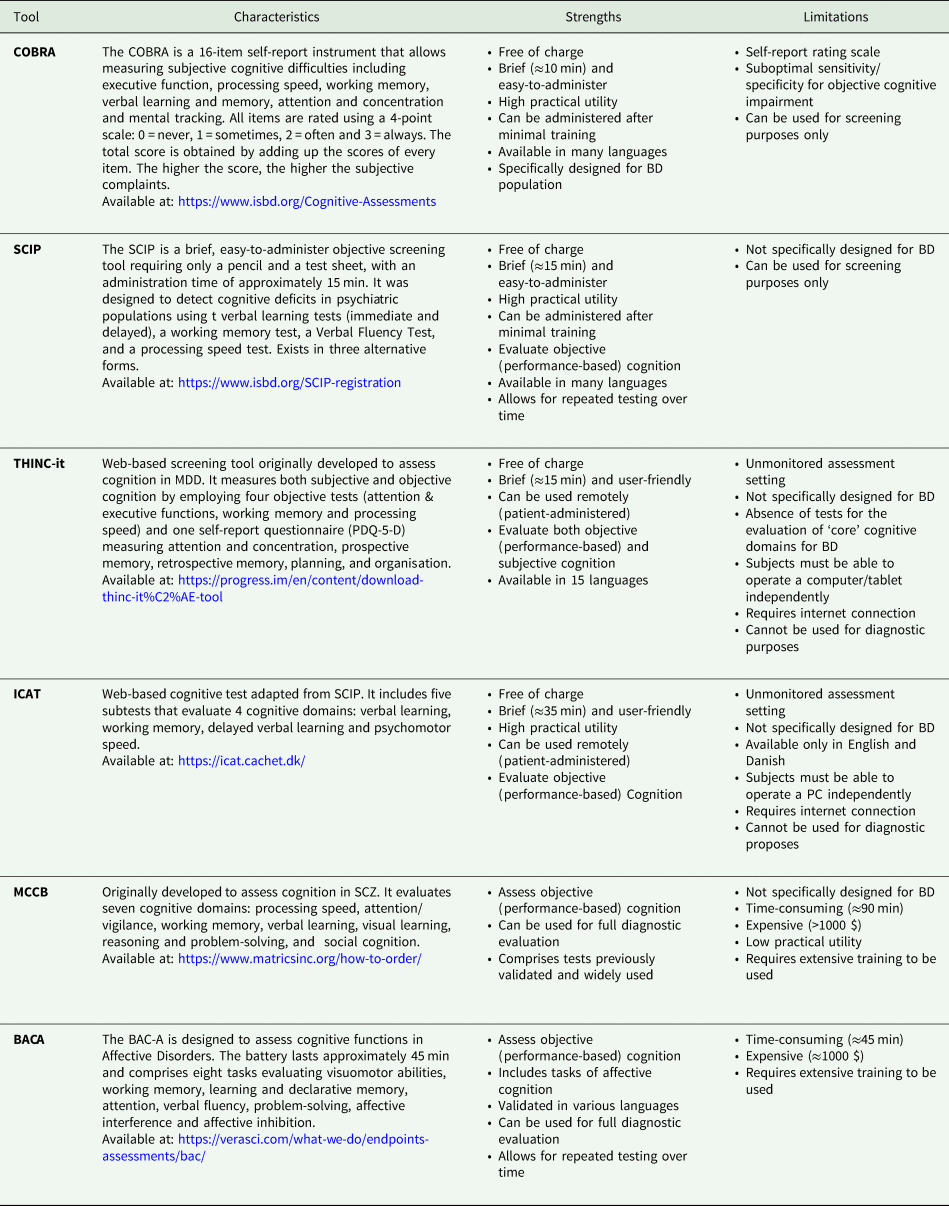

In this commentary, we critically appraised the strengths and limitations of the tools most commonly used to assess cognition in BD (Table 1). What emerges is that there are no tools more appropriate than others per se, as the suitability and clinical applicability of these instruments may depend on multiple factors. Among others, the target population (e.g. young vs elderly patients; people able vs not able to operate a computer); the purpose of the evaluation (e.g. cognitive screening vs exhaustive diagnostic evaluation; single evaluation vs monitoring over time); the characteristics of the tool itself (e.g., self-report vs performance-based; paper-and-pencil vs computerized; free of charge vs on payment); (iv) the clinical setting (e.g., presence of qualified vs unqualified staff; time and space resources). Based on these factors, we propose a diagram that may help healthcare professionals to make the best use of the instruments described above. The diagram visually summarises both the characteristics of each tool and the cognitive assessment process. As regards the properties of the tools, we used icons under each tool name (and listed in the caption) which refer to administration time, the need for the clinician, the psychometric property of the instrument, whether the tool is performance- or self-report-based and, finally, if it is on payment. As for the assessment process, the clinician is first asked to screen and/or monitor (“screening and/or monitoring” in the upper part of the schema) the patient's cognitive performance using one of four instruments (THINC-it, ICAT and COBRA and SCIP) based on the need for a computer (i.e., PC yes/no). If deficits are found at this point, the healthcare professional can proceed to a II-level assessment, choosing between BACA and MCCB. Otherwise, a stop icon warns the clinician to interrupt the evaluation. We acknowledge that this diagram is a preliminary proposal deriving from our clinical and research experience with BD patients. Thus, it would need to be further studied and possibly endorsed by other research groups.

Table 1. Characteristics, strengths and limitations of tools commonly used for cognitive assessment in BD

BACA, Brief Assessment of Cognition in Affective Disorder; BD, Bipolar Disorder; COBRA, Cognitive Complaints in Bipolar Disorder Rating Assessment; ICAT, Internet Based Cognitive Assessment Tool; MCCB, MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery; PDQ-5-D, Perceived Deficits Questionnaire for Depression; SCIP, Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry; SCZ, Schizophrenia; THINC-it, THINC-integrated tool.

Data

All data used to write this paper is in the reference list.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This study was partially supported by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Health (GR-2016-02361283 to CP).

Conflicts of interest

None.