Introduction

For a long time, the European political space had been structured on a single dimension of conflict, generally synthesized in the left–right ideological dimension. In the past two decades, this one-dimensional interpretation of political conflict has been widely questioned. In a series of studies, Kriesi and colleagues (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019) posit that socio-economic and cultural transformations, triggered by the globalization process, have favoured the emergence of a new ‘demarcation’ vs. ‘integration’ cleavage in Western Europe.

Kriesi and colleagues are not the only ones supporting this thesis, and several scholars have put forth different definitions and conceptualizations of the new cleavage (e.g. see Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2010; Teney et al., Reference Teney, Lacewell and De Wilde2014; Häusermann and Kriesi, Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; De Vries, Reference De Vries2018; Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Strijbis et al., Reference Strijbis, Helmer and De Wilde2020). Despite these different definitions, most agree in deeming this new line of political conflict as articulated on an economic (free trade vs. protectionism), cultural (pro- vs. anti-immigration), and institutional [pro- vs. anti-European Union (EU) integration] dimensions (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008: 11).

Although these studies provide empirical evidence of the structuring of such new cleavage, they are often limited in their scope. In some cases, their analyses deal with a small number of countries. In others, instead, although the focus is on a relatively large number of countries, data cover a fairly short period. Finally, these studies do not adopt a consistent conceptualization of the demarcation conflict. Some of them explicitly refer to a full-fledged transnational cleavage (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018), others instead conceive it more as a conflict or a divide (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; De Vries, Reference De Vries2018).Footnote 1 Therefore, it is still debated whether the demarcation vs. integration conflict can be understood as a proper cleavage (requirements for the application of ‘cleavage’ terminology will be discussed in the next section).

This study aims at shedding light on the alleged structuring of what we will call the demarcation cleavage. In particular, we address three research questions (RQs): (1) Has a new demarcation cleavage emerged in Europe? (2) If this is the case, how has it evolved over time across the European countries? (3) And, more specifically, what role does it play within the broader structure of competition of each party system?

In answering these questions, we outline the extent to which the demarcation cleavage has spread across Europe (RQ1) and its evolution over time (RQ2). To address RQ2, we develop an innovative framework which allows us to the different stages of the lifecycle of a cleavage and, more specifically, which specific stage has been reached in European countries. To do so, we rely on an original dataset (Emanuele et al., Reference Emanuele, Angelucci, Marino, Puleo and Vegetti2019) providing data on electoral volatility and its internal components in the elections for the European Parliament (EP) in all EU countries since 1979 (or the date of their accession to the Union). Most importantly, the dataset also provides data about electoral volatility for the demarcation bloc (i.e. bloc volatility),Footnote 2 that is the group of political parties that, based on their policy positions, can be classified as demarcationist.

The concept of bloc volatility has been introduced in the 1980s, in the stream of studies following the seminal contribution by Pedersen (Reference Pedersen1979) on electoral volatility (e.g. see Borre, Reference Borre1980; Bartolini, Reference Bartolini, Daalder and Mair1983; Mair Reference Mair, Daalder and Mair1983). Then, it was organically developed by Bartolini and Mair (Reference Bartolini and Mair1990 [Reference Bartolini and Mair2007]) in their analysis of the stabilization of the European electorate between the 1880s and the 1980s. Traditionally, bloc volatility has been used to analyse the class cleavage, but it can also be implemented to cover other cleavages.

The relevance of bloc volatility as a tool for assessing a cleavage’ strength in a society was originally clarified by Bartolini and Mair (Reference Bartolini and Mair1990 [Reference Bartolini and Mair2007]: 45), who posit, given that a cleavage divides the society into two opposing groups, we should expect that ‘the stronger the cleavage, therefore the less frequent is the exchange of votes across the dividing line’. This is because ‘the stronger the hold of a cleavage, the more difficulty individual voters will experience in crossing the boundary, and hence the lower will be the level of bloc volatility’ (Bartolini and Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990 [Reference Bartolini and Mair2007]: 46). As a result, bloc volatility is useful to capture the strength of a cleavage, as it is a proxy for the degree of electoral mobility of a given group.Footnote 3

Looking at bloc volatility alone, however, is not sufficient to capture the relative importance of the cleavage in the party system. To address RQ2, we will also focus on the electoral strength of the parties politicizing the demarcation bloc, with the underlining assumption that the electorally stronger the bloc, the stronger the related cleavage.

Moreover, to reconnect bloc volatility and the structure of political competition in each country (RQ3) – consistently with the relevant literature (Bartolini and Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990 [Reference Bartolini and Mair2007]: 49) – data on electoral mobility across the cleavage will be used in combination with a measure of cleavage salience.

In this article, we reconstruct the evolution of the demarcation cleavage across the 28 EU member states over the past 40 years. More into detail, we show the demarcation cleavage has emerged in most European countries, mobilizing over time a growing number of voters. In particular, this long-term trend has reached its highest peak in the 2019 EP elections. However, although the cleavage has become an important (if not the main) dimension of electoral competition, it has not reached maturity yet. As we explain later in the text, a mature cleavage is one which mobilizes a substantial portion of the electorate, and the latter is fairly stable across time, as voters are clearly divided into the two opposite sides of the cleavage and hardly cross the cleavage line to switch from a party belonging to one side to another one belonging to the other side.

The article is structured as follows: in the next section, we discuss the formation of the new demarcation vs. integration bloc in light of the cleavage theory. Then, in the third section, we present our data, and we identify the political parties that can be classified as belonging to the demarcation bloc in the EU. Then we move to present our analyses and our empirical results (fourth and fifth sections). We conclude the article by discussing our findings and their implications for future research.

Theoretical framework

For a long time, the Rokkanian conception of cleavage (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967; Rokkan, Reference Rokkan1970) has been (and still is) of paramount importance in the study of party system formation and voting behaviour in Western Europe. The concept of cleavage indicates a social conflict rooted in the political community and originating from certain ‘critical junctures’, namely, processes of profound social transformations (such as the nation-state formation, the industrial revolution, globalization, and so forth).

These transformations lead to the formation of different societal interests and, therefore, to the formation of opposing social blocs. The mere formation of distinct social blocs does not have necessarily political implications. Indeed, the blocs become politically relevant – and are consequently able to structure political conflict – only when: (1) they configure as a domain of identification; and (2) when they are mobilized by an organization (i.e. a political party). This means that the simple fracture between divergent social interests is not enough to signal the formation of a new cleavage, that is, a politicized conflict capable of structuring stable political alignments and oppositions in a country. This is basically the definition of cleavage that has been elaborated by Bartolini and Mair (Reference Bartolini and Mair1990 [Reference Bartolini and Mair2007]: 199). According to them, a cleavage is crucially defined by three fundamental elements: a conflict dividing the society into two distinct social groups, such as the distinction between the working class and the bourgeoisie (empirical element); a set of values and beliefs providing the social group(s) with a sense of identity and self-consciousness (normative element); and, finally, a manifest organizational structure that coordinates and inspires the collective action of the social group of reference and brings its interests into the political system.

According to Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967), four cleavages have emerged as a consequence of two macro-processes, namely, the formation of the modern state and the industrial revolution. Among the four cleavages, the one that confronts a working class with a bourgeoisie is the last to have been formed; and, even today, the literature is divided on the enduring capacity of this cleavage to structure party systems and guide voting behaviour.Footnote 4 Although the strength of the class cleavage is now put into question (i.e. Franklin, Reference Franklin, Franklin, Mackie and Valen1992, Reference Franklin, Franklin, Mackie and Valen2009, Reference Franklin2010), what we know is that such cleavage is articulated on an economic dimension and finds a synthesis in the more general left/right ideological dimension, that is, the primary source of political conflict in Western European politics (Fuchs and Klingemann, Reference Fuchs, Klingemann, Jennings and Van Deth1990).

In recent times, however, a new emerging strand of the literature has increasingly questioned the idea of a mono-dimensional space of political conflict summarized by the left/right dimension. This literature, instead, has advanced new multidimensional approaches to political competition. A first two-dimensional model of European political space is advanced by Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt1994), who distinguishes a first dimension of conflict, opposing socialism and capitalism (a conflict substantially overlapping with the left–right dimension), from a second cultural dimension differentiating between libertarianism and authoritarianism on issues such as abortion, gay rights, and so on.

Similarly, European politics scholars variously discuss the existence of a European dimension, orthogonal to the traditional left–right axis, centred on the opposition/support to the process of supranational integration (Hix and Lord, Reference Hix and Lord1997; Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe, Marks, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999). This antagonism on European integration has been increasingly considered as constituting a new independent source of political conflict. Among the earlier studies on the matter, the one by Hooghe and Marks (Reference Hooghe, Marks, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999) shows how the left–right axis is able to structure positions and policies in the economic field (even at the European level), whereas positions regarding national sovereignty and European integration represent an autonomous dimension (i.e. pro-/anti-EU integration). Moreover, their study also cements the idea of an independent, cultural dimension rooted in the so-called ‘new politics’.

This latter has become relevant, especially since the so-called silent/postmaterialist revolution (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1977) and concerns cultural issues such as the environment, immigration, ethnic minority rights, and so on. The combination of the economic and cultural dimensions of conflict is conceptualized as the ‘GAL/TAN scale’, opposing ‘Green, Alternative, Liberal’ stances and ‘Traditional, Authoritarian, Nationalist’ ones (Hooghe, Marks and Wilson, Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). Finally, in their analysis of cleavage politics, Hooghe and Marks (Reference Hooghe and Marks2018) understand globalization as the external shock at the base of radical societal changes, leading to the formation of a new transnational cleavage concerning political opposition to European integration and immigration.

In a series of articles and books, Kriesi and colleagues (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019) have effectively summarized the previous studies, consolidating the view of a two-dimensional political space. Here, a new dimension of conflict is added to the traditional economic axis subsumed under the right/left axis and pitting the ‘losers’ and ‘winners’ of globalization against each other. ‘Likely winners of globalization include entrepreneurs and qualified employees in sectors open to international competition, as well as all cosmopolitan citizens […] Losers of globalization, by contrast, include entrepreneurs and qualified employees in traditionally protected sectors, all unqualified employees, and citizens who strongly identify themselves with their national community’ (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008: 8).

Kriesi and colleagues (Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2008), therefore, as much as Hooghe and Marks, identify globalization as the driving force of social and political changes in recent decades and a critical factor in producing new sources of differentiation and inequalities in national communities. Kriesi and colleagues' starting point is the two-dimensional space discussed by Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt1994) and based on the opposition of an economic dimension of political conflict (socialism vs. capitalism) with a cultural one (libertarianism vs. authoritarianism). Globalization has transformed and radicalized the differences in both dimensions. Indeed, economic globalization has further increased the differences between right and left from an economic point of view, exacerbating the differences between supporters of protectionist policies, on the one hand, and supporters of policies of international economic integration, on the other hand.

Meanwhile, the process of European integration and the growing importance of migratory phenomena in Europe have structured a new cultural dimension calling into question traditional conceptions of national identity (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; on the link between EU integration, migration, and identity see also De Vreese and Boomgaarden, Reference De Vreese and Boomgaarden2005; Van Elsas and Van der Brug, Reference Van Elsas and Van der Brug2015; Otjes and Katasanidou, Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017). This new cultural dimension pits supporters of European integration and supporters of more open migration policies against supporters of sovereigntist policies and immigration closures.

Overall, the combination of these three aspects (economic, cultural, and institutional) is at the basis of a new demarcation cleavage.Footnote 5 The demarcation would distinguish precisely the positions of parties and voters supporting policies of economic, cultural, and institutional integration from those that, instead, fight against it. It is worth noting here that the demarcation cleavage, as we defined it, is clearly distinct from other possible cleavages that are present in society. Indeed, the fact that the demarcation cleavage also includes an economic dimension does not imply an overlap with the traditional class cleavage. The latter is articulated on a distinction in positions concerning the state intervention in the economy and social protection by means of the welfare state, rather than in terms of pro-anti economic integration stances (i.e. globalization). Indeed, mainstream parties of both the left and the right are argued to differ not in relation to their positions on economic integration (given both are considered as converging towards a position that, in general, favours global economic integration), but rather in terms of state intervention in the economy (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006: 926).

Summarizing, from an economic perspective, the cleavage divides between positions supporting liberal and pro-market positions with protectionist stances (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). From the cultural viewpoint, ‘a universalist, multiculturalist or cosmopolitan position is opposing a position in favour of protecting the national culture and citizenship in its civic, political and social sense’ (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008: 11).

Despite the growing number of studies claiming the emergence of a new dimension of political competition, it is still a matter of discussion whether the demarcation vs. integration bloc can be fully understood as a new cleavage. Indeed, studies supporting the idea of the formation of this new cleavage suffer from several shortcomings. In particular, we see here three major problems: (1) Focus on a narrow period: Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002), for example, rely mainly on the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES), which covers only a limited time span (their first study dates back to 2002 and makes use of the first wave of the CHES data collected in 1999). Not differently, De Vries (Reference De Vries2018) makes use of the CHES data at the party level and only one wave (2014) of the EES at the individual level, whereas Teney et al. (Reference Teney, Lacewell and De Wilde2014) rely only on one wave of the Eurobarometer (2009). (2) Limited number of countries and lack of variance: Kriesi and colleagues (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019), for example, ground their findings on a content analysis of mass media in just six European countries. Moreover, as noted by Otjes and Katasanidou (Reference Otjes and Katsanidou2017), these are countries subject to very similar conditions (e.g. all are net immigration countries). This means that, at least concerning one fundamental dimension of the new demarcation cleavage (i.e. immigration), there is a lack of variance across countries that could return biased results. More recently, Hutter and Kriesi (Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019) have extended their analysis to 15 European countries, including also Central and Eastern Europe. However, as in previous studies, their focus is still concentrated on the supply side of politics, thus limiting their possibility to accurately assess the structuring of a proper cleavage. (3) Lack of conceptual and operational clarity: as previously observed, some scholars refer to the concept of political conflict to define the demarcation vs. integration contraposition; some others explicitly refer to the concept of cleavage; others, instead, use the concept of cleavage as a synonymous of political conflict. This lack of conceptual clarity is oftentimes reflected in a poor operationalization of cleavage politics.

Our study intends to overcome these shortcomings by relying on an original dataset of electoral volatility in the EP elections (Emanuele et al., Reference Emanuele, Angelucci, Marino, Puleo and Vegetti2019). The dataset includes data on electoral volatility in the EP elections since 1979 and covers, over time, all the European member states.Footnote 6 These data allow us to leverage both cross-time and cross-country variance, providing us with the opportunity to get a more systematic and structured analysis of the formation of the demarcation cleavage.

Measurement

It is now time to discuss the identification of the alleged new demarcation vs. integration cleavage in empirical terms. In this regard, one has to concretely identify which are the political parties (if any) aligned on the demarcation/integration cleavage. To do so, we have based our analysis on the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) data (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2018), since 1979 until today in all EU states. We use the CMP as the source to establish the overall composition of demarcation bloc independently from the specific EP election (meaning that the inclusion/exclusion from the demarcation bloc is not conditional to specific characteristics of the EP elections).

All this given, we preferred the CMP over other data sources for several reasons. First, compared to most data sources, it covers a relatively longer period of time, thus fitting our purpose to study the evolution of the demarcation cleavage over the past 40 years. Second, although the CMP records party positions in national (and not European) elections, it is reasonable to assume that these are the positions that are truly relevant for both parties and voters, and that therefore reflects more accurately the profile of a party. Indeed, parties (and voters as well) conceive EP elections in relation to national politics and are more likely to convey information about their positions and their profile based on their manifestos in general elections rather than on their euromanifestos, which are almost unknown to most voters. Third, compared to other data sources (e.g. the Euromanifesto Project), the CMP includes a larger number of political parties, thus providing us with the chance to map the composition of the demarcation bloc more extensively.Footnote 7

The CMP has content-analysed party manifestos over time to gauge the party's relative emphasis on several issues. For each political party, the dataset reports the proportion of sentences and quasi-sentences (both positive and negative mentions) dedicated to each specific coded issue.

The inclusion/exclusion of different parties in the demarcation/integration bloc has been established on the basis of the three aspects that potentially define the new cleavage: each party's position on free trade and open markets,Footnote 8 EU,Footnote 9 and multiculturalism.Footnote 10 For each item, the party's position is the difference between the positive and negative poles in each electoral year. Subsequently, the resulting value has been weighted by the overall issue salience of that item, calculated as the sum of positive and negative mentions on each item:Party Position = (Positive mentions − Negative mentions) × (Positive mentions + Negative mentions)

Thanks to this calculation, it has been possible to obtain an index ranging from negative to positive values: 0 indicates a neutral party position on a specific item, whereas negative (positive) values signal a party position close to (away from) the demarcation pole of the item. For each of these three items, a score has been assigned to all political parties in each election. Subsequently, an average score has been calculated for each item (separately) across the period under scrutiny (1979–2019). As a result, a unique value for each of the three items has been associated with each party. A measure of party position on the demarcation–integration cleavage has been finally obtained as a result of a mean – for the 1979–2019 period – of the means of party scores on each of the three items included in this study.Footnote 11 This operationalization is consistent with previous literature on cleavages (e.g. Bartolini and Mair Reference Bartolini and Mair1990 [Reference Bartolini and Mair2007]) where the belonging of a party to a given side of the cleavage does not change over time by definition. Therefore, in our study, the demarcation bloc is understood as a time-invariant dichotomous variable (parties either belong or not to the demarcation bloc).

After a summary score for each item has been calculated for all parties, we classified a party in the demarcation bloc only if the following conditions are met: (1) the mean party score on the three items is negative and (2) at least two items out of three (i.e. free trade, Europeanism, and multiculturalism) have a negative score.Footnote 12

The list of parties obtained through this procedure has been further subjected to a qualitative screening. Fifty-one political parties belonging to the demarcation bloc across the 28 EU countries have been finally identified (Table 1).Footnote 13

Table 1. List of parties in the demarcation bloc, EU (1979–2019)

Source: Codebook by Emanuele et al. (Reference Emanuele, Angelucci, Marino, Puleo and Vegetti2019).

The important element displayed in the table that positively addresses our first RQ about the existence of a new demarcation cleavage is not merely the number of parties politicizing the cleavage (51), but mostly the fact that as many as 20 out of 28 countries have at least one party included in the list. This means that, based on our classification of the demarcation bloc, the politicization of the cleavage has occurred widely throughout Europe.

Evidence: national and temporal variations in Europe

To address our second RQ about the evolution of a new demarcation cleavage, let us look at some key variables representing indicators of cleavage strength. To do so, it is useful to move from the party to the systemic level. In each country, all parties belonging to the same side of the cleavage, outlined in Table 1 above, shall be considered as a single bloc. The first indicator of interest is the electoral strength of the demarcation bloc. For each country in each EP election, we have collected the aggregate vote share of all parties belonging to the demarcation bloc. In this way, the higher the vote share of parties belonging to the bloc, the more relevant the cleavage, at least in electoral terms.

Then, the second indicator of interest is the degree of electoral mobility across the cleavage line. Here, it is necessary to resort to the concept – and measure – of bloc volatility. This latter refers to the net change in the aggregate vote share of all parties included in a bloc – in this case, the demarcation one – between two consecutive elections.

Empirically, Demarcation Bloc Volatility (DemBV), is an internal component of Total Volatility (TV). Although the latter is the net change in the aggregate vote share between two consecutive elections, the former measures the net aggregate vote switching between the two sides of a cleavage, in this case, the Demarcation Bloc.Footnote 14 As a consequence, DemBV can range between 0 and TV, but can never exceed it. If DemBV equals 0, it means that there are no net aggregate shifts between the two sides of the cleavage.Footnote 15 In other words, parties belonging to the demarcation bloc receive the same aggregate share of votes in two consecutive elections.Footnote 16 Conversely, just from a speculative viewpoint, if DemBV equals TV, it means that all net aggregate shifts between two consecutive elections occur between the two sides of the cleavage.Footnote 17

We are aware that net aggregate volatility may not perfectly correspond to individual, gross, volatility. This latter is the result of three different mechanisms: vote switching, turnout change – that is, demobilization and remobilization waves – and generational replacement – namely, old cohorts of voters passing away and being replaced by younger cohorts of voters. All else equal, the higher the turnout change compared to the previous election and the higher the generational replacement, the lower the accuracy of net volatility as a proxy for individual vote switching. However, Gomez (Reference Gomez2018) finds an almost perfect correlation (0.97) between party-level volatility, measured by the Pedersen index, and individual vote switching in general elections.Footnote 18 Overall, ‘research employing the Pedersen index can rest assured that volatility is by and large reflecting the net effect of party-switching’ (Gomez, Reference Gomez2018: 190).

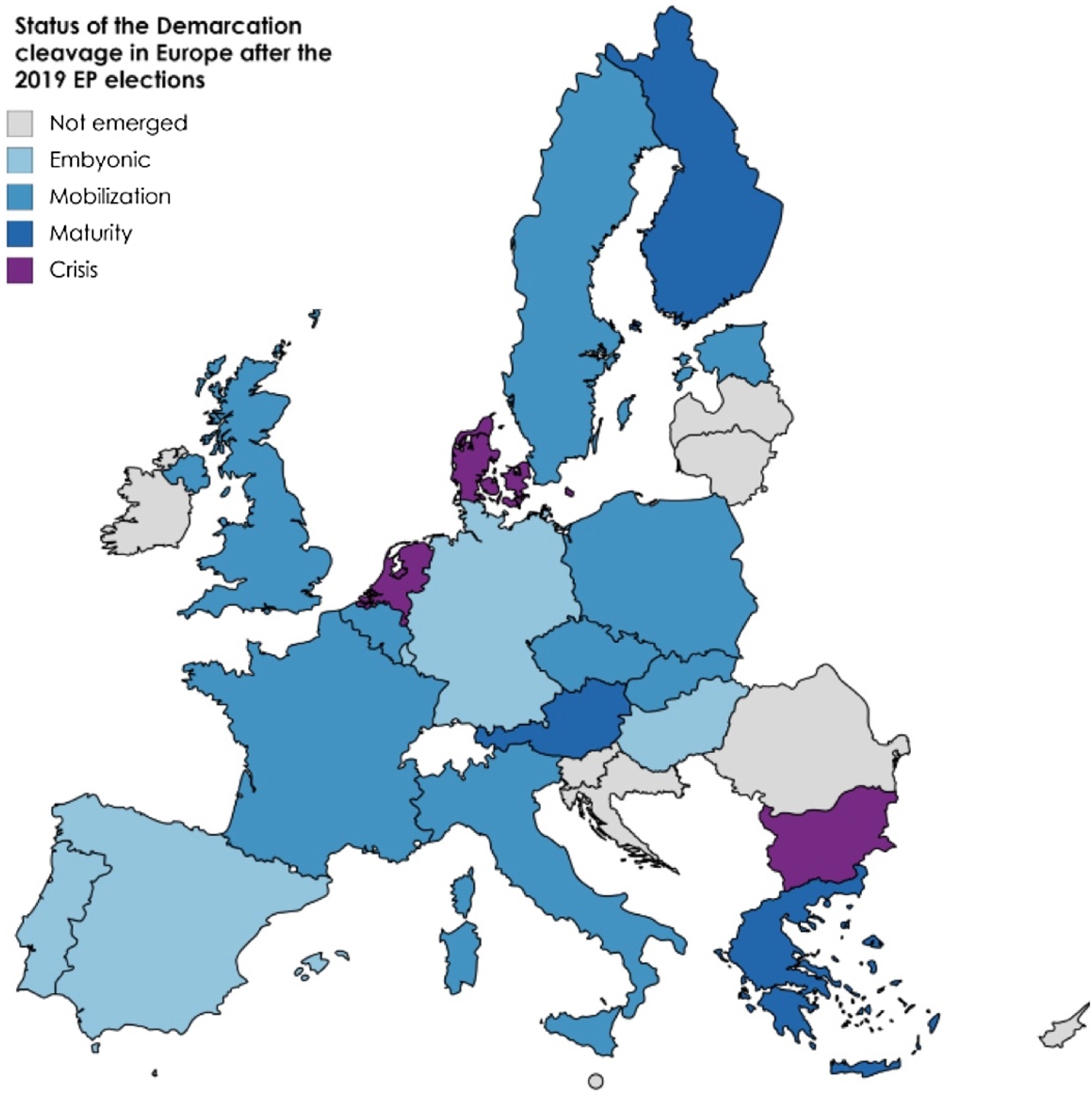

Although the use of the electoral strength as a proxy for the strength of the cleavage is evident, the interpretation of DemBV is a bit more complicated. The interpretation of this second indicator depends upon the degree of maturity of a given cleavage. Let us make this clearer by recurring to a graphical visualization in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The lifecycle of a cleavage.

As shown in Figure 1, each cleavage has a certain lifecycle, namely, it might reach certain stages of development. From an electoral viewpoint, a cleavage becomes politically relevant when a political entrepreneur exploits the political opportunity emerged in the society by creating a new party emphasizing the emerging conflict or by reorienting an existing party towards one side of the cleavage.

In the first stage of its lifecycle (Embryonic), the new cleavage has only limited relevance in a party system, as the party (or the parties) politicizing it receive(s) a tiny share of votes and, therefore, also the electoral volatility associated to the cleavage is very limited.

Then, in the second stage (Mobilization), the cleavage becomes more relevant by mobilizing an increasing share of the electorate. In this context, the electoral mobility across the cleavage line increases as well, as new voters abandon their former allegiances and move towards the parties emphasizing such new cleavage. This last process is exactly what occurred in the class cleavage at the turn of the First World War, as documented by Bartolini and Mair (Reference Bartolini and Mair1990 [Reference Bartolini and Mair2007]).

The subsequent stage is the stabilization of the cleavage (Maturity) and is reached when the cleavage mobilizes a relevant portion of the electorate that is stable across elections, namely, that shows a very limited electoral mobility across the cleavage line. In historical terms, this stage was experienced, for traditional cleavages, by the freezing of political alignments in Western Europe between the 1920s and the end of the 1960s (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967).

Finally, a cleavage may enter a process of Crisis when it experiences increasing electoral mobility due to an electoral decline compared to previous elections. In this case, high-electoral mobility across the cleavage line signals that voters do not consider that conflict as relevant anymore, as they move across the cleavage line frequently. This is what occurred to the class cleavage starting from the 1970s, when the traditional cleavage politics has progressively lost its ability to structure individual electoral choices in many Western countries (Franklin, Reference Franklin, Franklin, Mackie and Valen1992).

Of course, a cleavage might not pass through all these stages. For instance, there might be a cleavage that never reaches its Maturity by moving directly from a period of Mobilization to a subsequent Crisis.

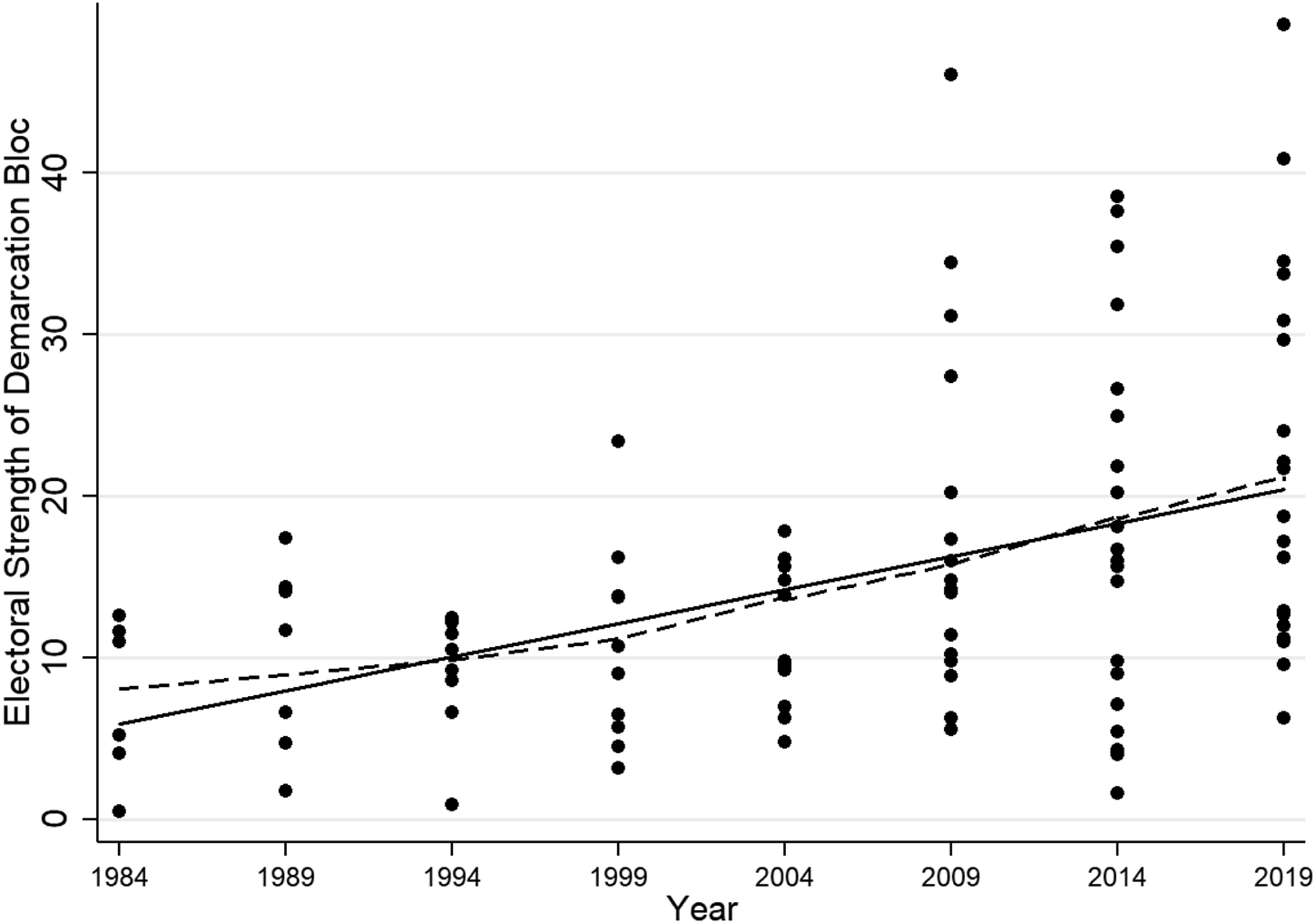

Moving from this theoretical scheme to the empirical results, Figure 2 plots the aggregate electoral strength of the demarcation bloc in all EP elections over time since 1984.Footnote 19

Figure 2. Electoral strength of the demarcation bloc in Europe over time.

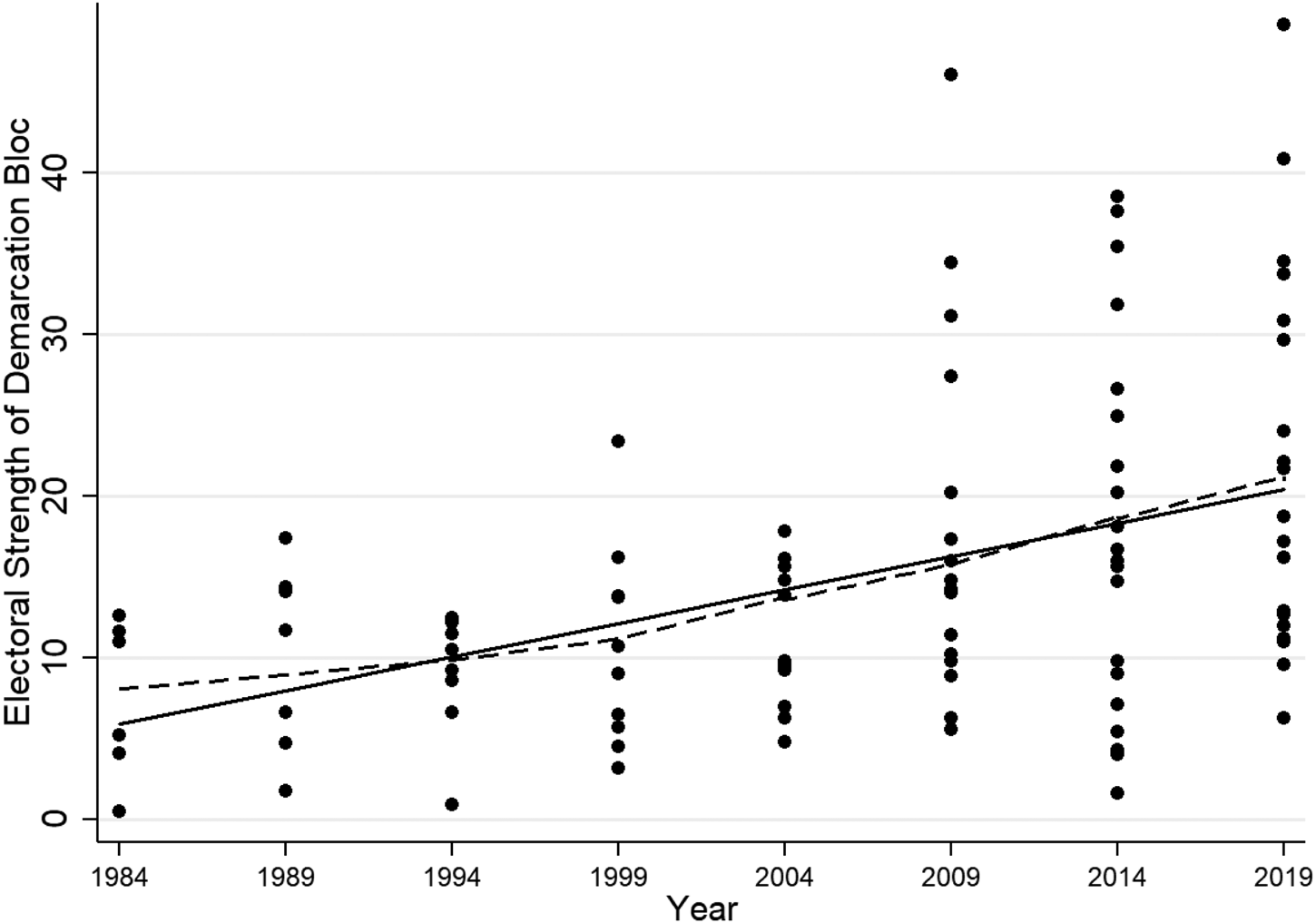

The striking evidence that we get from this figure is that the cleavage has experienced a process of growing electoral strength over time, particularly after 2004. The average support for the parties emphasizing demarcation was only 7.5% in 1984, then it ranged between 9 and 11.4 between 1989 and 2004, and since then it rocketed up to 21.2% in the 2019 EP election. The increase over time witnesses a rallying of voters who have moved towards demarcation parties. With specific reference to the most recent EP election, as displayed in Figure 3, the support for demarcation parties ranges from 6.3% in Spain – thanks to the rise of the new right-wing party Vox – to an astonishing 49.1% in Poland – given the electorally dominant Law and Justice and the newly emerged Kukiz’15. Just below Poland, the Western European country with the strongest support for demarcation parties is Italy, where the Northern League and the small right-wing Brothers of Italy collected almost 41% of the vote share in the 2019 EP election. The Italian result is even more surprising, given it is not a country experiencing a long-term relevance of the demarcation cleavage – unlike Austria, Denmark, and France – but, instead, a country where the support for parties emphasizing demarcation has skyrocketed in recent years (+31 percentage points between 2014 and 2019). Indeed, today, demarcation parties in Italy average twice the European mean (equal to 21.2).

Figure 3. Electoral strength of the demarcation bloc in Europe in 2019: national variations.

Over these 35 years, the demarcation bloc has experienced not only an increase in its electoral strength but also an increase in the electoral mobility of voters across the cleavage line. Figure 4 reports the trend over time of DemBV in Europe.

Figure 4. Electoral mobility of the demarcation bloc in Europe over time.

Similarly to the electoral strength, and not surprisingly given the trend in the former, the electoral mobility across the cleavage line has increased over time, moving from 3 to 7.9 between 1984 and 2019. Until the 1999 period, the cleavage was barely electorally relevant, and this might help explain the very low electoral mobility in that period. However, this latter was not a sign of consolidation, but a sign of the embryonic stage of the cleavage. An exception was France, where, in 1984, the emergence of the National Front mobilized, for the first time, French voters on this new dimension of competition and contributed to a DemBV equal to 11 in that EP election (the only visible outlier until the turn of the millennium).

Then, in the 2000s, the demarcation cleavage starts mobilizing increasingly relevant portions of the electorate, and this long-term trend reaches its highest peak in the 2019 EP election. However, such a noticeable upward trend in electoral mobility is still comparatively lower than the one observed in Figure 2 for the electoral strength of the cleavage. This is confirmed in Table 2, which reports the result of two regression analyses related to the effect of time on, respectively, the electoral strength (Model 1) and the electoral mobility (Model 2) of the demarcation cleavage. The models also control for countries' fixed effects.

Table 2. OLS regression analysis of time on electoral strength and electoral mobility of the demarcation cleavage

b coefficients and standard errors are reported. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The effect of time is significant on both indicators taken into account, but the level of confidence is higher in the case of electoral strength (P < 0.001 vs. P < 0.01). In particular, the electoral strength of the demarcation bloc has increased, on average, by some 0.55% each year since 1984,Footnote 20 whereas the level of bloc volatility has increased only by 0.20.

These findings bring us to an important conclusion in terms of the stage of development reached so far by the cleavage, our second RQ. The demarcation cleavage in Europe has been increasing its relevance over time and has been paired with a slow process of consolidation, given that the electoral mobility across the cleavage line has grown at a slower pace compared to the electoral strength.

Of course, this is just an overall picture, which hides important national variations across Europe. The map depicted in Figure 5 summarizes the status of the demarcation cleavage in the 28 EU countries after the 2019 EP election.

Figure 5. Status of the demarcation cleavage in Europe after the 2019 European Parliament (EP) election.

Beyond the eight countries where the demarcation bloc has never emerged yet (Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, and Slovenia), we find a group of five – mainly Western European – countries (Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Spain) where the cleavage is at an Embryonic stage. Therefore, in these countries, demarcation parties do exist (take Alternative for Germany, or Vox in Spain), but their electoral support is comparatively lower than the European average, and also the electoral mobility of voters is smaller than the European average. In these countries, it will be the next elections that will be decisive for assessing the evolution of the lifecycle of the cleavage. At that time, if an increase in the support by voters were paired with rising electoral mobility, this would witness a passage in these countries of the demarcation cleavage towards a Mobilization phase, that has not been reached yet.

By contrast, Figure 5 shows there are as many as nine European countries (Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Sweden, and United Kingdom) where the demarcation cleavage has already reached Mobilization. In these countries, a higher percentage of voters compared to the 2014 European election supports parties politicizing the demarcation cleavage, and there is also a high level of electoral mobility, above the European average of 5.14. This means that a growing portion of the electorate has been abandoning traditional parties competing on old lines of conflict and moving towards parties emphasizing demarcation. In this group, we find Italy, already mentioned above regarding the very high-electoral strength of demarcation parties in the 2019 EP election. Moreover, there are also other countries where demarcation parties have experienced a noticeable upsurge (the United Kingdom Independence Party and the Brexit Party in the UK, the French National Front and Unbowed France, Flemish Interest in Belgium, and so forth). All in all, in these countries, the demarcation cleavage has been transforming into an important line of conflict, at least as shown at EP elections.

There are also three Western European countries (Austria, Finland, and Greece) where the demarcation cleavage has reached a further stage, that of Maturity. Here, parties politicizing the cleavage are central actors of the party system and, in some cases, have also held governing positions (let us just mention the Freedom Party of Austria, the True Finns, and the Greek Syriza), confirming the importance and relevance of the demarcation cleavage in their party systems. The key feature of countries having reached the Maturity stage is that, despite the remarkable vote share received by the demarcation bloc (i.e. above the European average for the 2019 European elections), the electoral mobility across the cleavage line is limited (below the European average for 2019): in such situation, voters will hardly cross the cleavage boundary, as they perceive the cleavage itself as highly critical.

Finally, in three countries (Bulgaria, Denmark, and the Netherlands), we find the final possible stage of the lifecycle of a cleavage. Indeed, here, the demarcation cleavage has experienced a Crisis: not only is there a retrenchment of demarcation parties, who have received a lower share of votes compared to 2014, but we also observe a level of electoral mobility across the cleavage line higher than the 2019 European average, and it is not surprising to notice that, in 2019, the Danish People's Party and the Dutch Party for Freedom are two political formations that have experienced a marked decline in their electoral support.

It should be mentioned that this crisis in the demarcation cleavage, coming so fast upon its maturation in three countries, is somewhat surprising in light of our expectation that social cleavages should exhibit durability – indeed durability of social cleavages (so much that they used to be referred to as ‘frozen’) was once seen as their most salient feature. The absence of durability for the demarcation cleavage in three countries does raise questions (that cannot as yet be addressed with existing data) regarding their real status.Footnote 21 This must be a topic for future research.

Putting demarcation into context: a new dimension of competition?

In the previous section, we have seen that relative majority of European countries after the 2019 EP elections, including four out of the six biggest countries (France, Italy, Poland, and the UK) are experiencing a phase of Mobilization in the lifecycle of the demarcation cleavage. However, so far, we have just assessed the evolution of the demarcation cleavage within the theoretical framework of a cleavage's lifecycle. Indeed, we have outlined where the cleavage does not exist, where it is yet in an embryonic stage, where it has been mobilizing an increasing share of the electorate, and, finally, where it has reached noticeable stability and strength. Nonetheless, we still do not know how this cleavage is located within the broader structure of competition of each country.

Let us give an example. Imagine a country where the demarcation cleavage shows a high level of electoral mobility compared to other countries. Such amount of bloc volatility may represent just a tiny and negligible percentage of the total electoral interchange occurring between two given electoral periods. Or, instead, such bloc volatility may represent the total amount of volatility in a system. These two opposite situations imply that to gauge the relative importance of the cleavage within a given national context, looking only at the electoral mobility across the cleavage line is not sufficient.

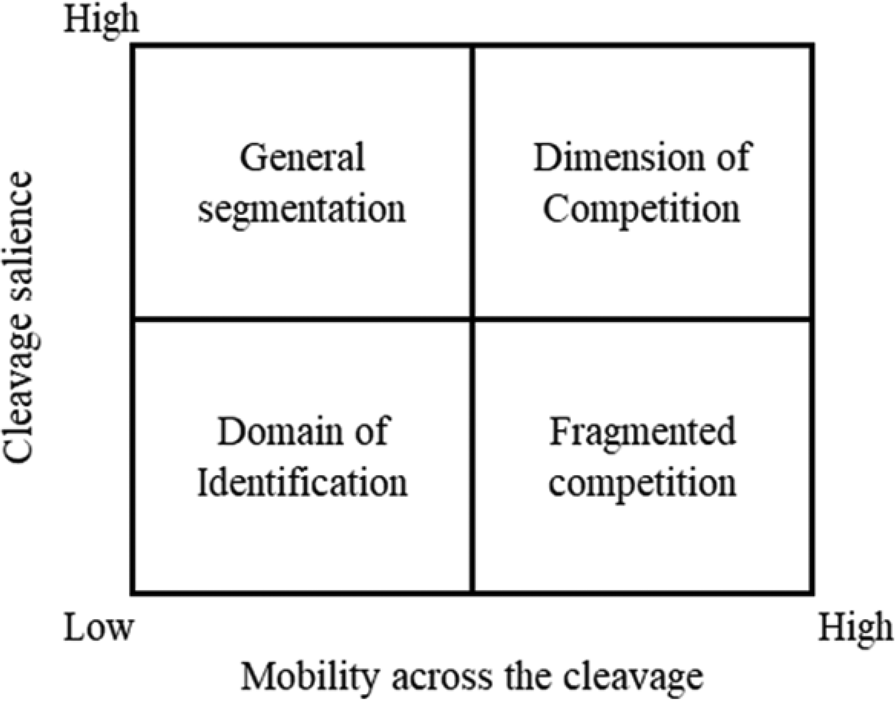

To put the demarcation cleavage into context, thus capturing its relative importance within the party system of each country (RQ3), we present the concept (and measure) of Cleavage Salience. This is simply the ratio between bloc volatility (in this case, DemBV) and TV. As reported by Bartolini and Mair (Reference Bartolini and Mair1990 [Reference Bartolini and Mair2007]: 49), who first introduced this concept regarding the class cleavage, cleavage salience is ‘a measure which does not tell us something about the cleavage itself, but rather about its relative weight within the broader cleavage structure of the system’. By combining the previously introduced measure of electoral mobility across the cleavage (DemBV) with cleavage salience, we can build a typology of the role played by the demarcation cleavage within the general structure of competition of each country.

Given the structure of the typology reproduced in Figure 6, we expect that most observations fall either in the lower left or in the upper right quadrants. This is because if the electoral mobility across the demarcation bloc is limited, all else equal, it is likely that also the salience of demarcation, within the broader context of competition, will be relatively low. Conversely, if such electoral mobility is high, we expect that, all else equal, this cleavage will be much salient in the national electoral competition. As a result, out of the four quadrants, two are particularly relevant and indicate two important potential roles played by a given cleavage within each country's electoral competition: a cleavage can, therefore, be a domain of identification or a dimension of competition.Footnote 22

Figure 6. Cleavage electoral mobility and salience: a typology.

The first situation means that the electoral change in a country is not significantly linked to the cleavage, as other dimensions of conflict contribute to TV. In this context, the votes for parties emphasizing the cleavage are ‘frozen’, in the sense that the electoral support for these parties barely changes over time. Of course, this situation can be achieved either when the cleavage is Embryonic – and the overall support for parties politicizing this cleavage is relatively lowFootnote 23 – or when such cleavage is in its Maturity – when the electoral support for these parties is relatively high. All in all, regardless of the relative electoral strength of a cleavage, what is important to underline here is that voters hardly cross the cleavage line from a comparative viewpoint.

Instead, the second situation (upper right quadrant) depicts a context where the cleavage is, instead, an important – if not the main – dimension of competition. Here, voters move across the cleavage line, and these shifts are salient, namely, they represent a high proportion of the total electoral interchange of the country.

The two residual (and less likely) situations are, instead, those represented in the upper left and lower right quadrants. In the first case, we are in a situation of general segmentation, given that, although the electoral mobility across the cleavage line is relatively low, this represents a comparatively high proportion of TV. This situation means that not just our cleavage of interest, but all cleavages are domains of identification, and so there is substantially no competition and an extremely low percentage of vote shifts.

Finally, the second residual case shows an opposite situation where, despite the high-electoral mobility across the cleavage line, this latter represents only a small proportion of TV, which means that we are in a situation of fragmented competition, where our cleavage of interest is only one dimension of competition among many.

Our analysis of the demarcation cleavage in EP elections across time clearly shows a consistent pattern towards increasing importance of the cleavage as a dimension of competition. Before 2014, the overwhelming majority of elections (82%, 49 out of 60) fell in the two left quadrants, namely, general segmentation (eight elections) and identification (41). In the EP elections of 2014 and 2019, the ratio between identification and competition has reversed: in 2014, the number of elections falling in the two right quadrants has moved from 18 to 40% (i.e. eight out of 20), and this proportion increases to 60% in 2019 (12 out of 20).

These numbers underline an important process that has been going on: let us not forget that, over the 1979–2019 period, electoral volatility has almost doubled (Emanuele and Marino, Reference Emanuele, Marino, De Sio, Franklin and Russo2019). However, our analysis tells us that, despite this increase in electoral volatility, the mobility of the demarcation bloc has significantly increased as well over the same years (see Figure 4). As a result, the salience of the demarcation bloc has increased over time, which means that the weight of DemBV in TV has become bigger and bigger.

All in all, over the past 40 years, the European political space has become more fluid, and increasing electoral opportunities have been offered to political entrepreneurs attempting to politicize new lines of conflict.Footnote 24 Within this changing context, out of all the possible outcomes, it is the demarcation cleavage that seems to have won the struggle for existence, by imposing itself as a more and more central dimension of competition.Footnote 25

The 2019 EP elections represent what is currently the latest stage of this long-term process. Figure 7 plots European countries in 2019 according to the typology introduced in Figure 6.Footnote 26 The chart excludes the eight countries where the demarcation bloc has not yet emerged. As mentioned earlier, out of the 20 countries where demarcation has been politicized, 12 fall in the right part of the figure, for the first time in European history. As explained above, the demarcation cleavage is a domain of identification both in countries where the cleavage is still only at an Embryonic stage, that is, Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Spain (see Figure 5), and also in countries where it has reached its Maturity, such as Finland, Greece, and Austria. This latter not only shows that demarcation is a domain of identification (the Freedom Party of Austria has remained relatively stable as a relevant actor in Austrian politics), but also other cleavages (i.e. class) are mainly domains of identification, so much so that the relatively low DemBV of the country is sufficient to be salient vis-à-vis TV, unlike what happens in all the countries in the Identification quadrant. This explains why Austria is the only one falling into the Segmentation quadrant.

Figure 7. Demarcation electoral mobility and salience in the 2019 EP elections.

As many as eight countries fall, instead, into the upper right quadrant: here, the demarcation cleavage is an important – if not the main – dimension of competition, given that DemBV is high and salient vis-à-vis TV. In this quadrant, we find countries that are in two different stages of the respective cleavage lifecycle: on the one hand, we have Belgium, France, Italy, Poland, and Sweden, that are experiencing a Mobilization phase, where voters have been so much mobilized by this new conflict that demarcation represents probably the main area of competition today. On the other hand, we find Bulgaria, Denmark, and the Netherlands, where demarcation is still an important dimension of competition, but it has recently entered a Crisis stage (see Figure 5). What strikingly emerges from this quadrant is the position of Italy as a real outlier: in the Belpaese, the mobility across the cleavage in 2019 has been impressive (31), and such electoral interchange represents almost the total amount of volatility recorded in the 2019 EP election in Italy (0.83). This finding patently tells us that the demarcation cleavage is the main – if not the sole – dimension of competition in the country.

Finally, in the remaining four countries (Czech Republic, Estonia, Slovakia, and the UK), the demarcation cleavage has indeed emerged as a dimension of competition, but not as the only one. Here, the cleavage has surfaced in a context of fragmented competition. This is because, notwithstanding the high voters' mobility across the cleavage line, the salience of such mobility is comparatively low, which means that other important dimensions of competition are at stake. Of course, these four countries have been faced with an extraordinarily fluid electoral environment (TV ranges from 33.05 in Estonia to 50.4 in the UK). In the UK, in particular, there have been further steps towards the mobilization of the demarcation cleavage (bloc volatility equals 7.1), but it has represented only a tiny fraction of the total electoral interchange in the country (with a salience equal to 0.14), where most of the electoral shifts have occurred within blocs and due to other dimensions of competition.Footnote 27

Conclusion

In this article, we have explored the evolution of the demarcation cleavage in the EP elections between 1979 and 2019. More and more studies have emphasized the increasing relevance of a new cleavage embracing the issue dimensions of globalization, European integration, and multiculturalism. Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, there is not a comprehensive study analysing the temporal evolution of the alleged demarcation cleavage in a comparative perspective.

To fill this gap, we have focused our attention on the structuring of such cleavage through a lifecycle perspective, thus presenting an innovative framework to understand the different stages of evolution of a given cleavage. More into detail, such framework has allowed us to detect which stage of the demarcation cleavage's lifecycle has been already reached in different EU countries. Moreover, we have also made a step forward by putting the new demarcation cleavage into the broader context of electoral competition in Europe. In this way, we have been able to grasp the role played by the demarcation cleavage in each country's party system vis-à-vis other potential dimensions of competition.

This article brings about three significant findings that may serve as the first steps for further empirical research. First, as our analysis was primarily devoted to understanding whether the alleged demarcation cleavage has been successfully politicized, our original classification shows the demarcation cleavage has actually emerged in 20 EU countries. The success of such politicization is variable, but significantly growing over time. Indeed, in recent decades and years, a larger number of voters have been abandoning traditional parties and moving towards political formations emphasizing demarcation issues.

This brings us to our second main finding, that refers to the stage of the lifecycle reached by the cleavage. Overall, and notwithstanding significant cross-country differences, the cleavage seems to be actually in a stage of mobilization, although it cannot be considered as a widespread stable and central line of division within each European party system yet.

Finally, the third finding emerges after putting the cleavage into the broader context of national electoral competitions. Over time, the demarcation cleavage has been evolving in many countries from a mere domain of identification for a tiny fraction of the electorate into an important – if not the main – dimension of competition. These dynamics have reached their peak so far in the 2019 EP elections.

Of course, we acknowledge that all the findings emerging from this article have its own inevitable limits as they result, on the one hand, from the fixed temporal scope of the classification and, on the other hand, from an empirical application that is exclusively related to the EP elections. As a result, our findings have not necessarily the ambition of being able to travel beyond the scope of this study. Nevertheless, this analysis may represent a first step for a new research agenda aimed at deepening our knowledge regarding this new cleavage.

This agenda should proceed along two different lines of research. The first concerns the use of individual-level data to assess the presence of collective beliefs and identity feelings among the members of the alleged social group of reference for the cleavage, that is, the ‘losers of globalisation’ (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). This development is not trivial, as the presence of common identity feelings among the members of the social group is a necessary element for the stabilization of the electorate across the cleavage line that we need to consider the demarcation cleavage as a mature one (Bartolini and Mair, Reference Bartolini and Mair1990 [Reference Bartolini and Mair2007]).

The second line of research is related to exploring the evolution of this cleavage over time, for instance also in the successive EP elections, to track the possible steps forward of the cleavage in its lifecycle. Then, a final point to be considered is a possible replication of this analysis with a focus on European national elections. Indeed, we are aware that, given the emphasis on European integration that characterizes the electoral campaigns before EP elections, these latter are a particularly favourable context for the politicization of the demarcation cleavage. In this way, general elections may represent a sort of robustness test to assess the structuring of such new cleavage properly, and they will also allow us to take into account a broader temporal perspective, by potentially including also general elections held before 1979.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2020.19

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this article has been presented at the SISE-SISP-ITANES Conference, Genoa, 4–5 July 2019; and at the XXXIII SISP Congress, Lecce, 11–14 September 2019. We warmly thank Mark Franklin, Luana Russo, Lorenzo De Sio, Alessandro Chiaramonte, Alessandro Pellegata, and Carolina Plescia for their comments and suggestion on earlier versions of this article. Moreover, we also thank Leonardo Puleo and Federico Vegetti for their help in data collection.