Introduction

During the organizational socialization period, newcomers experience a major adjustment of their cognitive schemes and develop an understanding of the mutual obligations that link them to the organization (De Vos, Buyens, & Schalk, Reference De Vos, Buyens and Schalk2003; Payne, Culbertson, Lopez, Boswell, & Barger, Reference Payne, Culbertson, Lopez, Boswell and Barger2015; Tekleab, Orvis, & Taylor, Reference Tekleab, Orvis and Taylor2013; see also Saks & Ashforth, Reference Saks and Ashforth1997). In this context, a perception of psychological contract breach whereby the organization is seen to have failed to fulfill its obligations toward newcomers is likely to have deleterious consequences (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997; Zhao, Wayne, Glibkowski, & Bravo, Reference Zhao, Wayne, Glibkowski and Bravo2007). Previous work suggested that breaches to the psychological contract occurring in the first few months after organizational entry may impede newcomer adjustment (Woodrow & Guest, Reference Woodrow and Guest2020). Theoretical explanations for the negative effects of psychological contract breach have focused on the key mediating role of employees' affective reactions (Cassar & Briner, Reference Cassar and Briner2011; Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wayne, Glibkowski and Bravo2007). More precisely, the perception of a breach to the psychological contract would trigger a negative emotional experience (e.g., anger, frustration or, more broadly, feelings of violation or mistrust) which would influence how newcomers think and act in the workplace. Although focusing on employees' affective reactions as mediators is worthwhile, as shown in a recent meta-analysis (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wayne, Glibkowski and Bravo2007), we argue that it does not fully capture newcomers' experience of psychological contract breach and that other approaches are worth considering.

Indeed, by directly focusing on employees' affective reactions as a mediating mechanism, researchers might overlook significant, overarching cognitive processes that could explain the relationship between psychological contract breach and work outcomes. In this regard, attributional processes (Heider, Reference Heider1958; Martinko, Harvey, & Dasborough, Reference Martinko, Harvey and Dasborough2011) appear particularly interesting. Indeed, individuals naturally make attributions regarding the causes of what they experience, and these attributions are known to have a substantial influence over their attitudes and behaviors (Martinko, Harvey, & Dasborough, Reference Martinko, Harvey and Dasborough2011). As Heider (Reference Heider1958) mentioned in his classical work, individuals tend to behave as naïve psychologists and seek to explain what they experience to better understand and adjust to their environment. Previous theoretical work on psychological contracts (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997; Rousseau, Reference Rousseau1995; Turnley & Feldman, Reference Turnley and Feldman1999) suggests, in this regard, that employees try to make sense of the reasons why psychological contract breach has occurred. For example, Morrison and Robinson (Reference Morrison and Robinson1997; see also Lester, Turnley, Bloodgood, & Bolino, Reference Lester, Turnley, Bloodgood and Bolino2002) suggested that different attributions possibly lead to different outcomes, with employees reacting more negatively to intentional contract breach. Building on this work, Ng, Feldman, and Butts (Reference Ng, Feldman and Butts2014) suggested that supervisors may be seen, to some extent, as responsible for contract breach. However, this possibility has yet to be empirically examined.

The present study aims to fill this gap. We seek to contribute to the literature on psychological contracts by testing the premises of an attributional perspective of psychological contract breach. We argue that newcomers cognitively attribute psychological contract breach to a lack of trustworthiness of their supervisor (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995), which is defined as the attributes or characteristics of the supervisor, including ability, benevolence, and integrity, that inspire trust (Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Reference Colquitt, Scott and LePine2007). Indeed, supervisors are likely to be central targets of newcomers' attributions given their role as salient socialization agents (Nifadkar, Reference Nifadkar2020; Saks & Ashforth, Reference Saks and Ashforth1997; Zou, Tian, & Liu, Reference Zou, Tian and Liu2015) and given that, as proximal representatives of the organization, they are gatekeepers of the organization's promises (Dabos & Rousseau, Reference Dabos and Rousseau2004; Solberg, Lapointe, & Dysvik, Reference Solberg, Lapointe and Dysvik2020; Welander, Blomberg, & Isaksson, Reference Welander, Blomberg and Isaksson2020; Woodrow & Guest, Reference Woodrow and Guest2020). Supervisors are also directly accountable for some aspects of the realization of the psychological contract, including the arrangement of promised obligations on behalf of the organization (Coyle-Shapiro & Shore, Reference Coyle-Shapiro and Shore2007; Dabos & Rousseau, Reference Dabos and Rousseau2004; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Turnley, Bloodgood and Bolino2002; Solberg, Lapointe, & Dysvik, Reference Solberg, Lapointe and Dysvik2020; Welander, Blomberg, & Isaksson, Reference Welander, Blomberg and Isaksson2020; Woodrow & Guest, Reference Woodrow and Guest2020). Thus, the extent to which they are perceived to fulfill their roles in a trustful manner might explain the breach's effect on newcomer voluntary turnover. Specifically, we contend that the benevolence (i.e., a willingness to ‘do good’ to the employee) and integrity (i.e., adherence to acceptable principles and values) dimensions of trustworthiness, but not the ability (i.e., competence and skills) dimension (Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Reference Colquitt, Scott and LePine2007; Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995), will play a mediating role between contract breach and outcomes due to them implying a responsibility of the supervisor for contract breach (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997). We specifically focus on voluntary turnover as the key outcome because the intermediate paths between contract breach and voluntary turnover are debated in the recent literature (Clinton & Guest, Reference Clinton and Guest2014; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wayne, Glibkowski and Bravo2007) and supervisor trustworthiness remains a neglected mechanism in this process that bears implications for employees' future in the organization (Dirks & Ferrin, Reference Dirks and Ferrin2002).

Moreover, in light of recent psychological contract research emphasizing the key role of individual dispositions (e.g., Gardner, Huang, Niu, Pierce, & Lee, Reference Gardner, Huang, Niu, Pierce and Lee2015; Shih & Chuang, Reference Shih and Chuang2013; see also Rousseau, Hansen, & Tomprou, Reference Rousseau, Hansen and Tomprou2018), we argue that the aforementioned attributional process is moderated by newcomers' level of negative affectivity (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988). Indeed, as newcomers do not have developed yet a clear frame of reference to understand their environment, their experiences are likely to be affected by their dispositions (Eberl, Ute, & Möller, Reference Eberl, Ute and Möller2012; Saks & Ashforth, Reference Saks and Ashforth1997). This is because dispositions may play a more salient role in explaining how individuals make sense of situations and respond to them in times of uncertainty (Saks & Ashforth, Reference Saks and Ashforth1997). We specifically focus on negative affectivity (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988), which has been largely overlooked in organizational socialization research (for a recent exception, see Vandenberghe, Panaccio, Bentein, Mignonac, Roussel, & Ben Ayed, Reference Vandenberghe, Panaccio, Bentein, Mignonac, Roussel and Ben Ayed2019). Yet, research in other domains (e.g., pay satisfaction; Begley & Lee, Reference Begley and Lee2005) has demonstrated that negative affectivity involves a pessimistic view of the world. Employees with high levels of negative affectivity tend to expect negative fallouts and get prepared for negative situations (Judge & Larsen, Reference Judge and Larsen2001). Consequently, when they experience something negative, they are less surprised and react less negatively (Begley & Lee, Reference Begley and Lee2005; Judge & Larsen, Reference Judge and Larsen2001). We argue that the specific way of thinking and behaving that is associated with negative affectivity is important in connection with psychological contract breach. Thus, we aim to contribute to the literature by examining its role. More specifically, we contend, in line with the met expectations hypothesis (Begley & Lee, Reference Begley and Lee2005), that newcomers with high negative affectivity will be less likely to question their supervisor's trustworthiness after having experienced contract breach and will ultimately be less likely to leave as a result. In other words, we hypothesize that the impact of breach on supervisor trustworthiness and, indirectly, on voluntary turnover will be reduced among newcomers with high negative affectivity.

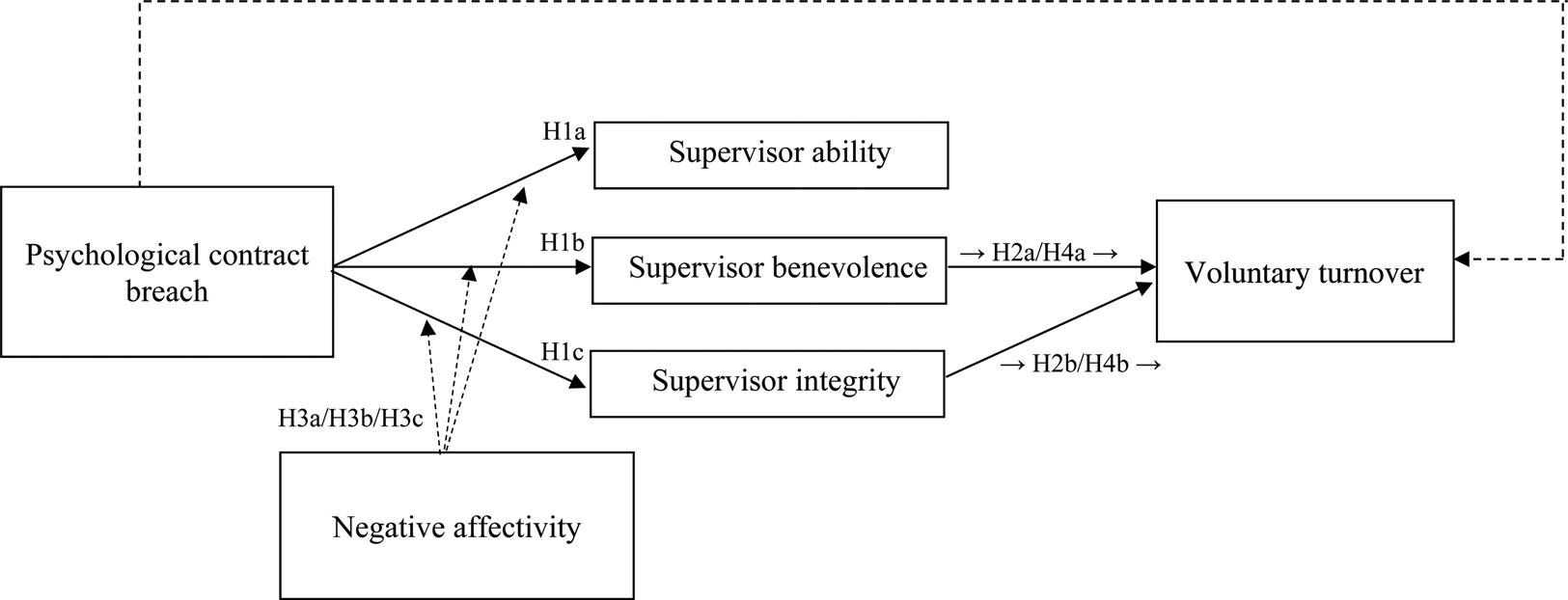

Adopting an alternative, attributional perspective to examine psychological contract breach's effects is a worthwhile research endeavor as contract breach is experienced by a high proportion of employees and its effects can be long-lasting and difficult to repair (Conway & Briner, Reference Conway and Briner2002; Conway, Guest, & Trenberth, Reference Conway, Guest and Trenberth2011; Robinson & Rousseau, Reference Robinson and Rousseau1994). It is also particularly important among newcomers, who, following organizational entry, actively seek to understand the terms of the psychological contract and assess whether and why it has been breached (De Vos, Buyens, & Schalk, Reference De Vos, Buyens and Schalk2003; Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997; Payne et al., Reference Payne, Culbertson, Lopez, Boswell and Barger2015; see also Rousseau, Hansen, & Tomprou, Reference Rousseau, Hansen and Tomprou2018). Organizations may also benefit from ensuring that they begin their relationship with employees on a positive note (Woodrow & Guest, Reference Woodrow and Guest2020). Considering that trustworthiness dimensions are distinguishable from, and more specific than, trust, and incrementally predict work outcomes over and above trust (Colquitt & Rodell, Reference Colquitt and Rodell2011; Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Reference Colquitt, Scott and LePine2007; Legood, Thomas, & Sacramento, Reference Legood, Thomas and Sacramento2016), this study is also timely and relevant as it will help determine which facets of trustworthiness are critical to newcomers' experience. Finally, examining the moderating role of negative affectivity is worthwhile as it will help to test the viability of the met expectations hypothesis (Begley & Lee, Reference Begley and Lee2005) in the context of attitudinal and behavioral reactions to contract breach, which, to our knowledge, has not been done to date. Doing so contributes to expand research on the role of trait affectivity during organizational socialization (Vandenberghe et al., Reference Vandenberghe, Panaccio, Bentein, Mignonac, Roussel and Ben Ayed2019). It also contributes to answer calls (Rousseau, Hansen, & Tomprou, Reference Rousseau, Hansen and Tomprou2018) to improve understanding of the role played by individual dispositions in the psychological contract breach process. Our research model is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research model and hypotheses for the study.

Theoretical background and hypothesis development

Psychological contract and psychological contract breach

The psychological contract is an implicit agreement between employees and their organization (Robinson, Reference Robinson1996; Rousseau, Reference Rousseau1995, Reference Rousseau2001). More specifically, the psychological contract captures employees' beliefs about the organization's obligations toward them as well as their beliefs about their own obligations toward the organization (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997; Robinson & Morrison, Reference Robinson and Morrison2000; Rousseau, Hansen, & Tomprou, Reference Rousseau, Hansen and Tomprou2018). These beliefs may concern salary and benefits or training and development opportunities, among other possibilities, and often reflect promises that employees perceive were being made to them (Herriot, Manning, & Kidd, Reference Herriot, Manning and Kidd1997; Rousseau, Hansen, & Tomprou, Reference Rousseau, Hansen and Tomprou2018; Solberg, Lapointe, & Dysvik, Reference Solberg, Lapointe and Dysvik2020). When employees perceive that the organization has failed to fulfil its obligations toward them, the psychological contract is said to be breached (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997). Thus, psychological contract breach is a subjective experience (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997; Robinson, Reference Robinson1996). It reflects employees' perception of what the organization delivered versus did not deliver but not necessarily what the organization actually delivered or not (Robinson, Reference Robinson1996). Psychological contract breach can hinder newcomers' adjustment to the organization and, as suggested by Woodrow and Guest (Reference Woodrow and Guest2020: 114), has ‘the potential to damage the developing employment relationship, leading to negative attitudes and behaviour, poorer social relationships, inhibited learning, and, potentially, turnover.’

Psychological contract breach and supervisor trustworthiness

Rooted in social psychology, attribution theories explore how individuals make attributions about the causes of what they experience and how this process affects their attitudes and behaviors (Kelley, Reference Kelley1973; Kelley & Michela, Reference Kelley and Michela1980; Martinko, Harvey, & Dasborough, Reference Martinko, Harvey and Dasborough2011; Weiner, Reference Weiner1986; see also Tomlinson & Mayer, Reference Tomlinson and Mayer2009). Of importance, research suggests that the nature of the attributions individuals make is critical to determine their responses (Kelley, Reference Kelley1973; Zapata, Olsen, & Martins, Reference Zapata, Olsen and Martins2013; see also Little, Roberts, Jones, & DeBruine, Reference Little, Roberts, Jones and DeBruine2012; Rule, Krendl, Ivcevic, & Ambady, Reference Rule, Krendl, Ivcevic and Ambady2013). Attributional theories have been used in recent research to explain how individuals respond to actions by organizations (Munyon, Jenkins, Crook, Edwards, & Harvey, Reference Munyon, Jenkins, Crook, Edwards and Harvey2019), supervisors (e.g., Lapointe, Vandenberghe, Ben Ayed, Schwarz, Tremblay, & Chenevert, Reference Lapointe, Vandenberghe, Ben Ayed, Schwarz, Tremblay and Chenevert2020; Matta, Sabey, Scott, Lin, & Koopman, Reference Matta, Sabey, Scott, Lin and Koopman2020), and coworkers (Puranik, Koopman, Vough, & Gamache, Reference Puranik, Koopman, Vough and Gamache2019), among other referents. Building on these recent research developments, we suggest that, in the organizational context, newcomers seek to attribute the plausible causes of contract breach to supervisor behaviors demonstrating a lack of trustworthiness.

Trustworthiness (which should not be confounded with trust itself; Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Reference Colquitt, Scott and LePine2007) refers to the personal characteristics of a party that foster trust from another party (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995). Following Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman (Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995), these separate yet related characteristics are ability, benevolence, and integrity. Ability is that group of skills, competencies, and characteristics that enable a trustee to have influence within some specific domain. It captures the ‘can-do’ dimension of trustworthiness (Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Reference Colquitt, Scott and LePine2007). Benevolence is the extent to which a trustee is believed to wish the good of the trustor, excluding egocentric motives. Integrity is defined as the perception that the trustee adheres to a set of principles that the trustor finds acceptable and acts in accordance with these principles. By describing whether the trustee will be willing to use his or her abilities to act in ways that favor the trustor, benevolence and integrity capture the ‘will-do’ aspects of trustworthiness (Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Reference Colquitt, Scott and LePine2007). Thus, our reasoning is that supervisor behaviors may be viewed as indicating a lack of ability, benevolence, and integrity, when employees experience psychological contract breach.

First, psychological contract breach could be attributed to a lack of ability of the supervisor. For example, failing to help a deserving newcomer benefit from organizational policies (e.g., training and development) or failing to master important aspects of one's supervisory role refers to lack of supervisor ability (Searle & Dietz, Reference Searle and Dietz2012; Treadway et al., Reference Treadway, Hochwarter, Ferris, Kacmar, Douglas, Ammeter and Buckley2004). Psychological contract breach could also be attributed to a lack of benevolence of the supervisor. A negative or cynical orientation of the supervisor toward newcomers, whereby the best interests of newcomers are left behind, could, for instance, be an explanation for contract breach (Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Reference Colquitt, Scott and LePine2007; Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995). Finally, psychological contract breach could be attributed to a lack of integrity of the supervisor. This would happen when supervisors fail to follow up on particular promises they made in the name of the organization because they do not endorse them anymore or because these promises do not match their own interests (Coyle-Shapiro & Shore, Reference Coyle-Shapiro and Shore2007; Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997). Thus, the three dimensions of trustworthiness are likely to be affected by breach. Our reasoning is supported by previous research suggesting that employees' perception of being treated unfairly (which is closely related to contract breach perceptions; Rosen, Chang, Johnson, & Levy, Reference Rosen, Chang, Johnson and Levy2009) influences the extent to which the supervisor is viewed as being trustworthy (Colquitt & Rodell, Reference Colquitt and Rodell2011; Frazier, Johnson, Gavin, Gooty, & Snow, Reference Frazier, Johnson, Gavin, Gooty and Snow2010). Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1a: Psychological contract breach will be negatively related to perceived supervisor ability.

Hypothesis 1b: Psychological contract breach will be negatively related to perceived supervisor benevolence.

Hypothesis 1c: Psychological contract breach will be negatively related to perceived supervisor integrity.

Relationship between contract breach and voluntary turnover: supervisor benevolence and integrity as mediators

As suggested in previous research (e.g., Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Reference Colquitt, Scott and LePine2007; see also Legood, Thomas, & Sacramento, Reference Legood, Thomas and Sacramento2016), trustworthiness dimensions are likely to exert differential effects on employee outcomes such as voluntary turnover. One key issue for supervisor trustworthiness acting as a mediator between contract breach and voluntary turnover is whether a lack of trustworthiness suggests that breach was intentional (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Turnley, Bloodgood and Bolino2002; Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997). This is because, according to attribution theories and related social psychology research (Kelley, Reference Kelley1973; Little et al., Reference Little, Roberts, Jones and DeBruine2012; Rule et al., Reference Rule, Krendl, Ivcevic and Ambady2013; Zapata, Olsen, & Martins, Reference Zapata, Olsen and Martins2013), individuals take actions that are consistent with the meaning associated with their attributions. Thus, trustworthiness dimensions that indicate a voluntary contribution (i.e., a responsibility) of the supervisor for contract breach should lead to voluntary turnover while those that do not should not have the same deleterious effect.

We expect low supervisor benevolence and integrity (i.e., ‘will do’ factors), but not low ability (i.e., a ‘can do’ factor), to indicate intentional contract breach (Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Reference Colquitt, Scott and LePine2007). These predictions are consistent with previous work in the field of betrayal and trust repair (Elangovan & Shapiro, Reference Elangovan and Shapiro1998; Tomlinson & Mayer, Reference Tomlinson and Mayer2009) that suggests that low benevolence and integrity, but not low ability, are associated with perceptions that trustees are responsible for their actions and willingly break their promises toward trustors. In effect, newcomers generally perceive supervisors as purposely deciding whether they care about subordinates' well-being, value their relationship with them, and demonstrate goodwill toward them (Elangovan & Shapiro, Reference Elangovan and Shapiro1998; Tomlinson & Mayer, Reference Tomlinson and Mayer2009). Thus, they should perceive benevolence as being intentional in nature. Similarly, newcomers should consider that supervisors have the power to decide whether they act in accordance with principles acceptable to them and respect their rights (Elangovan & Shapiro, Reference Elangovan and Shapiro1998; Tomlinson & Mayer, Reference Tomlinson and Mayer2009). As a result, they should also interpret supervisor integrity as reflecting purposeful or intentional behavior.

Taken together, these arguments suggest that, when newcomers experience contract breach, they may come to think that this has occurred due to a lack of benevolence and integrity on the part of their supervisor, as being low on these dimensions implies that one has willingly failed to fulfill one's obligations toward newcomers. As it is known that newcomers are liable to quick voluntary turnover decisions (e.g., Boswell, Boudreau, & Tichy, Reference Boswell, Boudreau and Tichy2005; Farber, Reference Farber1994), it is thus likely that contract breach will result in voluntary turnover through perceptions of low supervisor benevolence and integrity. In contrast, supervisor ability should not act as a mediator since it is generally associated with involuntary contract breach (Elangovan & Shapiro, Reference Elangovan and Shapiro1998). Thus, we propose the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 2a: Supervisor benevolence will mediate a positive relationship between psychological contract breach and voluntary turnover.

Hypothesis 2b: Supervisor integrity will mediate a positive relationship between psychological contract breach and voluntary turnover.

Negative affectivity as a moderator

Although the above discussion underlines the important role of attributions in explaining the role of supervisor trustworthiness dimensions in the psychological contract breach process, this process is also likely shaped by newcomers' dispositions (Martinko, Harvey, & Dasborough, Reference Martinko, Harvey and Dasborough2011; Saks & Ashforth, Reference Saks and Ashforth1997). Negative affectivity, which represents the tendency to experience negative emotions such as distress, fear, irritation, or guilt (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988), is particularly relevant to consider as a moderator of contract breach's effects.

Indeed, high-negative affectivity individuals are more vigilant than their low-negative affectivity counterparts to signs of impending punishment or frustration (Judge & Larsen, Reference Judge and Larsen2001). Essentially, individuals high in negative affectivity are thus more likely to view their new environment as hostile and threatening (Bowling, Hendricks, & Wagner, Reference Bowling, Hendricks and Wagner2008; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988). They would expect negative things to happen and develop pessimistic views of the organization (Thoresen, Kaplan, Barsky, Warren, & de Chermont, Reference Thoresen, Kaplan, Barsky, Warren and de Chermont2003). They are also more likely to ascribe ‘malicious motives’ to others (Penney & Spector, Reference Penney and Spector2005: 781). Similarly, high-negative affectivity individuals have been reported to perceive greater injustice (Thoresen et al., Reference Thoresen, Kaplan, Barsky, Warren and de Chermont2003). Thus, as they tend to prepare for the worst, newcomers with high negative affectivity may be less sensitive to the occurrence of negative events, such as psychological contract breach. As contract breach is consistent with their negative expectations, they should be less likely to seek explanations when it occurs and to attribute breach to low supervisor trustworthiness. Relatedly, supervisors' level of benevolence and integrity should not constitute major drivers of the decision to leave the organization among newcomers with high negative affectivity. Therefore, negative affectivity is expected to act as a ‘reducer’ of the relationship between breach and supervisor trustworthiness dimensions and of the indirect relationship between breach and voluntary turnover via supervisor benevolence and integrity.

In support of our reasoning, evidence from related domains suggests that high-negative affectivity individuals react less strongly to negative events or situations. For example, Begley and Lee (Reference Begley and Lee2005) found that high-negative affectivity individuals reacted less strongly to negative changes in bonus awards, which these authors attributed to their negative expectations. Similarly, Fisher and Locke (Reference Fisher, Locke, Cranny, Smith and Stone1992) demonstrated that high-negative affectivity individuals were less likely to react to job dissatisfaction, whereas Lopina, Rogelberg, and Howell (Reference Lopina, Rogelberg and Howell2012) found these individuals to be less likely to re-evaluate the negative aspects of their job and leave the organization as a result. Our reasoning is also aligned with the fact that high-negative affectivity individuals tend to inhibit their behavior, especially in new environments, which is typical of newcomers' situation (Judge & Larsen, Reference Judge and Larsen2001; Saks & Ashforth, Reference Saks and Ashforth1997). Thus, based on a met expectations hypothesis (Begley & Lee, Reference Begley and Lee2005; Wanous, Poland, Premack, & Davis, Reference Wanous, Poland, Premack and Davis1992), high-negative affectivity newcomers should expect contract breaches to occur, hence should be less likely to question their supervisor's trustworthiness for these events, and ultimately leave the organization as a result. This leads to our remaining hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3a: Negative affectivity moderates the negative relationship between psychological contract breach and supervisor ability, such that this relationship is weaker at high levels of negative affectivity (vs. stronger at low levels of negative affectivity).

Hypothesis 3b: Negative affectivity moderates the negative relationship between psychological contract breach and supervisor benevolence, such that this relationship is weaker at high levels of negative affectivity (vs. stronger at low levels of negative affectivity).

Hypothesis 3c: Negative affectivity moderates the negative relationship between psychological contract breach and supervisor integrity, such that this relationship is weaker at high levels of negative affectivity (vs. stronger at low levels of negative affectivity).

Hypothesis 4a: Negative affectivity moderates the indirect relationship between psychological contract breach and voluntary turnover through supervisor benevolence such that this indirect relationship is weaker at high levels of negative affectivity (vs. stronger at low levels of negative affectivity).

Hypothesis 4b: Negative affectivity moderates the indirect relationship between psychological contract breach and voluntary turnover through supervisor integrity such that this indirect relationship is weaker at high levels of negative affectivity (vs. stronger at low levels of negative affectivity).

Method

Sample and procedure

We contacted organizations and professional or alumni associations in Canada likely to have newcomers among their members. Five organizations and associations, representing an overall number of 26,553 individuals, agreed to participate in the study. More specifically, these organizations and associations agreed that we contact their employees/members to invite them to complete the study's questionnaires on a voluntary basis. Prospective participants were contacted through emails that described the study's purpose and the target population (i.e., newcomers). Emails also specified that responses would remain confidential. The Time 1 questionnaire included, among others, measures of psychological contract breach, negative affectivity, supervisor trustworthiness, and demographics. In total, 935 individuals responded to the Time 1 questionnaire on a voluntary basis. Among them, 272 were excluded because they reported having more than 1 year of tenure, which is the conventional cut-off for being considered as a newcomer (see Bauer, Bodner, Erdogan, Truxillo, & Tucker, Reference Bauer, Bodner, Erdogan, Truxillo and Tucker2007). Eight months after Time 1, the same participants who had completed the Time 1 questionnaire were surveyed about their organizational membership status (i.e., voluntary turnover). A total of 243 individuals provided information related to voluntary turnover. In the final sample (N = 243), most respondents were women (79%) and the average age was 27.9 years (SD = 6.4). Respondents mostly worked full-time (58%) and most held a university degree (76%). About half (53%) of them have been graduated since less than 1 year. The most common types of occupations/jobs in the sample were healthcare jobs, including nurses, nurse assistants, physiotherapists, physicians, medical technologists, and medical archivists (26.3%), and law-related occupations, including lawyers (18.1%). Most participants (97%) responded to the French version of the questionnaires.

We checked whether sample attrition led to non-random sampling across time (Goodman & Blum, Reference Goodman and Blum1996). Using logistic regression, we tested whether the probability of answering the follow-up questionnaire was predicted by Time 1 psychological contract breach, supervisor trustworthiness dimensions, negative affectivity, and demographics (gender, age, tenure, type of newcomer [recent graduate vs. seasoned worker], language, and dummy-coded organization/association membership variables). The result of the regression model predicting the probability of remaining in the sample at Time 2 was significant (ΔNagelkerke R 2 = .07, p < .01). Three individual predictors, psychological contract breach, supervisor ability, and language, were significant (B = –.28, p < .01; B = –.37, p < .05; B = 1.05, p < .05). This suggests that sample attrition was not entirely random. We later discuss this as a limitation.

Measures

Participants recruited for the study completed all the measures. Well-established, validated scales were used to measure the study's variables. We translated English-language measures into French using a standard translation-back-translation procedure (Brislin, Reference Brislin, Triandis and Berry1980). A 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) was used for all measures, except for the negative affectivity measure, for which items were answered on a scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Psychological contract breach

Robinson and Morrison's (Reference Robinson and Morrison2000) 5-item scale was used to measure contract breach (e.g., ‘I have not received everything promised to me in exchange for my contributions’). In this study, this scale displayed excellent reliability (α = .96). The reliability obtained in this study is similar to the reliability reported in Robinson and Morrison's study (α = .92) and in recent studies using this scale (e.g., Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Chang, Johnson and Levy2009; α = .91).

Supervisor trustworthiness

Supervisor trustworthiness dimensions were measured using Mayer and Davis's (Reference Mayer and Davis1999) 17-item scale (e.g., ability: ‘My supervisor is well qualified’; 6 items, α = .89; benevolence: ‘My supervisor is very concerned about my welfare’; 5 items, α = .90; integrity: ‘My supervisor has a strong sense of justice’; 6 items, α = .86). The very good reliabilities obtained for the three trustworthiness dimensions in this study are similar to those reported by Mayer and Davis (Reference Mayer and Davis1999; αs = .85 and .88 for ability, αs = .87 and .89 for benevolence, and αs = .82 and .88 for integrity) and in recent research using the same scales (e.g., Holtz, De Cremer, Hu, Kim, & Giacalone, Reference Holtz, De Cremer, Hu, Kim and Giacalone2020: αs = .94, .96, and .96 for ability, αs = .92, .94, and .93 for benevolence, and αs = .96, .97, and .97 for integrity).

Negative affectivity

We used a 10-item scale from Watson, Clark, and Tellegen (Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988) to assess negative affectivity (e.g., ‘upset’). These items were preceded by the phrase ‘In general, I feel…’. The scale displayed strong reliability in this study (α = .84). The reliability obtained in this study is comparable to the reliability reported by Watson, Clark, and Tellegen (Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988) when using similar time instructions (i.e., ‘In general’; α = .87). It is also similar to the reliability reported in recent research using Watson, Clark, and Tellegen's (Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988) scale and same ‘In general’ time instruction (e.g., Vandenberghe et al., Reference Vandenberghe, Panaccio, Bentein, Mignonac, Roussel and Ben Ayed2019; α = .85).

Voluntary turnover

Voluntary turnover was defined as a dichotomous outcome classifying any respondent either as a stayer (0) or a voluntary leaver (1) at Time 2. This treatment of the voluntary turnover variable is consistent with research practices (e.g., Arnold, Van Iddekinge, Campion, Bauer, & Campion, Reference Arnold, Van Iddekinge, Campion, Bauer and Campion2020; Clinton & Guest, Reference Clinton and Guest2014; Lopina, Rogelberg, & Howell, Reference Lopina, Rogelberg and Howell2012). Excluding cases of involuntary turnover (n = 7), the voluntary turnover rate was 15.2% in our sample.

Control variables

We controlled for age, gender, type of newcomer, and organizational tenure because these variables were previously found to be related to the study's variables or were found to be relevant in socialization contexts (Dirks & Ferrin, Reference Dirks and Ferrin2002; Grant & Sumanth, Reference Grant and Sumanth2009; Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, Reference Griffeth, Hom and Gaertner2000; Saks, Uggerslev, & Fassina, Reference Saks, Uggerslev and Fassina2007).

Results

Confirmatory factor analyses

The dimensionality of our data was examined through confirmatory factor analysis using LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, Reference Jöreskog and Sörbom2006) and the maximum likelihood method of estimation with a variance/covariance matrix as input. We compared our hypothesized model to more parsimonious models using χ2 difference tests (Bentler & Bonnett, Reference Bentler and Bonnett1980). The hypothesized five-factor model yielded a good fit to the data, χ2 (454) = 1,009.98, p < .001, RMSEA = .071, CFI = .96, NNFI = .96, SRMR = .074, and also improved significantly over more parsimonious four-factor models (Δχ2 = 140.76–801.83, Δdf = 4, p < .001) (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). Our constructs were thus distinguishable.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations are presented in Table 1. All variables displayed good internal consistency (αs > .70). Contract breach was negatively related to supervisor ability (r = –.37, p < .001), benevolence (r = –.50, p < .001), and integrity (r = –.55, p < .001). Contract breach was also positively related to voluntary turnover (r = .16, p < .05). Supervisor benevolence and integrity were both negatively related to voluntary turnover (r = –.15, p < .05, and r = –.19, p < .01, respectively). Finally, negative affectivity was negatively related to supervisor benevolence (r = –.13, p < .05) and integrity (r = –.12, p < .05), and positively related to voluntary turnover (r = .10, p < .05).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among study variables

Ns = 240–243. For voluntary turnover, 1 = voluntary leavers, 0 = stayers; for gender, 1 = female, 0 = male; for type of newcomer: 1 = recent graduate, 0 = seasoned worker. α coefficients are reported in parentheses along the diagonal.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Hypothesis tests

Hypotheses 1a–c

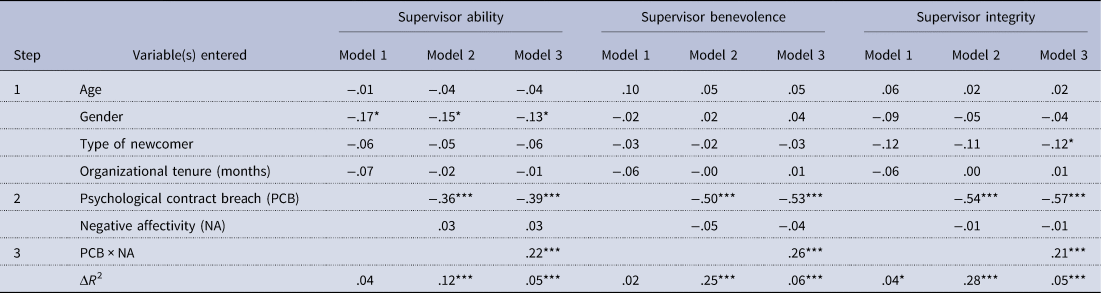

Multiple regression, with controls entered at Step 1, was used to test Hypotheses 1a–c. As can be seen from Table 2 (Model 2s), contract breach significantly and negatively predicted supervisor ability (β = –.36, p < .001), benevolence (β = –.50, p < .001), and integrity (β = –.54, p < .001). Therefore, Hypotheses 1a–c are supported.

Table 2. Results of moderated multiple regression analyses for supervisor trustworthiness dimensions

For gender: 1 = female, 0 = male; for type of newcomer: 1 = recent graduate, 0 = seasoned worker. Except for the ΔR 2 row, entries are standardized regression coefficients. Final model statistics: for supervisor ability: F (7, 232) = 8.64, p < .001, R 2 = .21; for supervisor benevolence: F (7, 232) = 16.16, p < .001, R 2 = .33; for supervisor integrity: F (7, 232) = 19.36, p < .001, R 2 = .37.

*p < .05; ***p < .001.

Hypotheses 2a–b

As a preliminary step before testing Hypotheses 2a–b, we used logistic regression to examine if supervisor integrity and supervisor benevolence predicted voluntary turnover, over and above control variables (Step 1) and contract breach (Step 2) (see Table 3) (Jaccard, Reference Jaccard2001; Liao, Reference Liao1994; Menard, Reference Menard2002). In Step 3, supervisor integrity significantly and negatively predicted voluntary turnover (B = –.68, p < .05) while supervisor benevolence did not (B = –.38, ns) (see Table 3, Model 3s). As we already know that contract breach is negatively related to supervisor integrity (β = –.54, p < .001; Table 2), we can now examine whether its indirect effect on voluntary turnover through supervisor integrity is significant. Consistent with Preacher and Hayes (Reference Preacher and Hayes2008), we used a bootstrap approach to test this indirect effect. The bias-corrected confidence interval (CI), as obtained from 5,000 bootstrap estimates, for the indirect effect of contract breach on voluntary turnover through supervisor integrity excluded zero (.27, 95% CI .02–.56), indicating a significant indirect effect. In contrast, the bias-corrected CI for the indirect effect of contract breach on voluntary turnover through supervisor benevolence did not exclude zero (.16, 95% CI –.06 to .43), indicating a non-significant indirect effect. Therefore, Hypothesis 2a is not supported while Hypothesis 2b is supported.

Table 3. Results of logistic regression analyses for voluntary turnover using supervisor benevolence and integrity as mediators

For gender: 1 = female, 0 = male; for type of newcomer: 1 = recent graduate, 0 = seasoned worker. The ΔR 2 row includes Nagelkerke ΔR 2 values. Model statistics for supervisor benevolence: Model 1: χ2 (4, N = 240) = .05, ns, −2LL = 206.92, constant = −1.48; Model 2: χ2 (5, N = 240) = 5.70, p < .05, −2LL = 200.60, constant = −2.38; Model 3: χ2 (6, N = 240) = 7.68, ns, −2LL = 198.66, constant = −.75. Model statistics for supervisor integrity: Model 1: χ2 (4, N = 240) = .05, ns, −2LL = 206.92, constant = −1.48; Model 2: χ2 (5, N = 240) = 5.70, p < .05, −2LL = 200.60, constant = −2.38, Model 3: χ2 (6, N = 240) = 10.11, p < .05, −2LL = 196.23, constant = .86.

*p < .05.

Hypotheses 3a–c

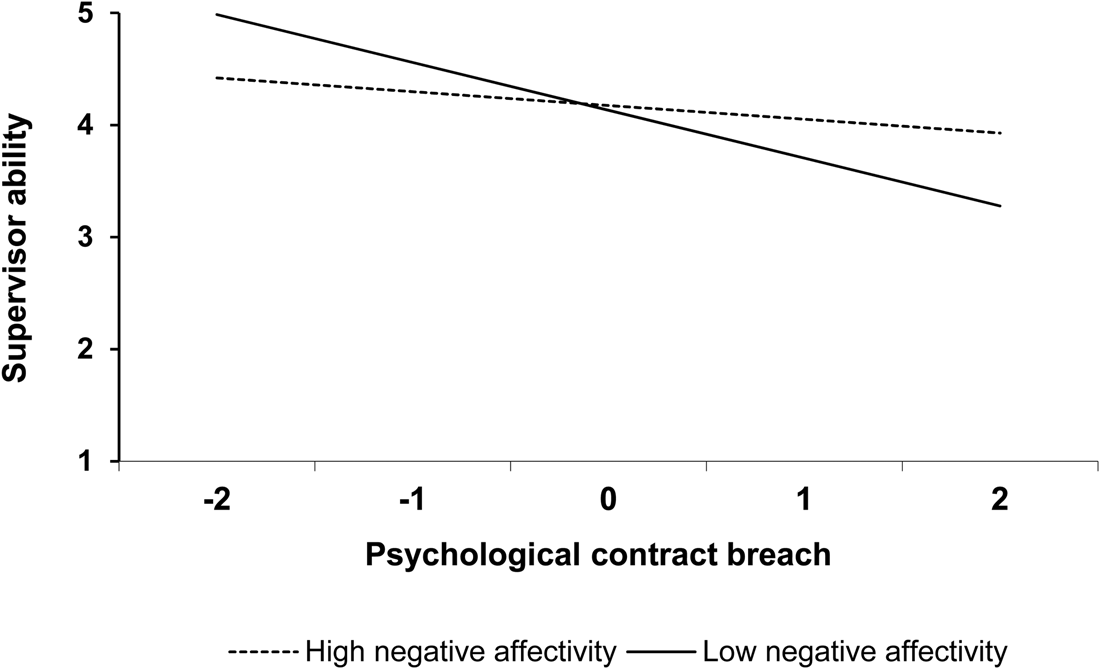

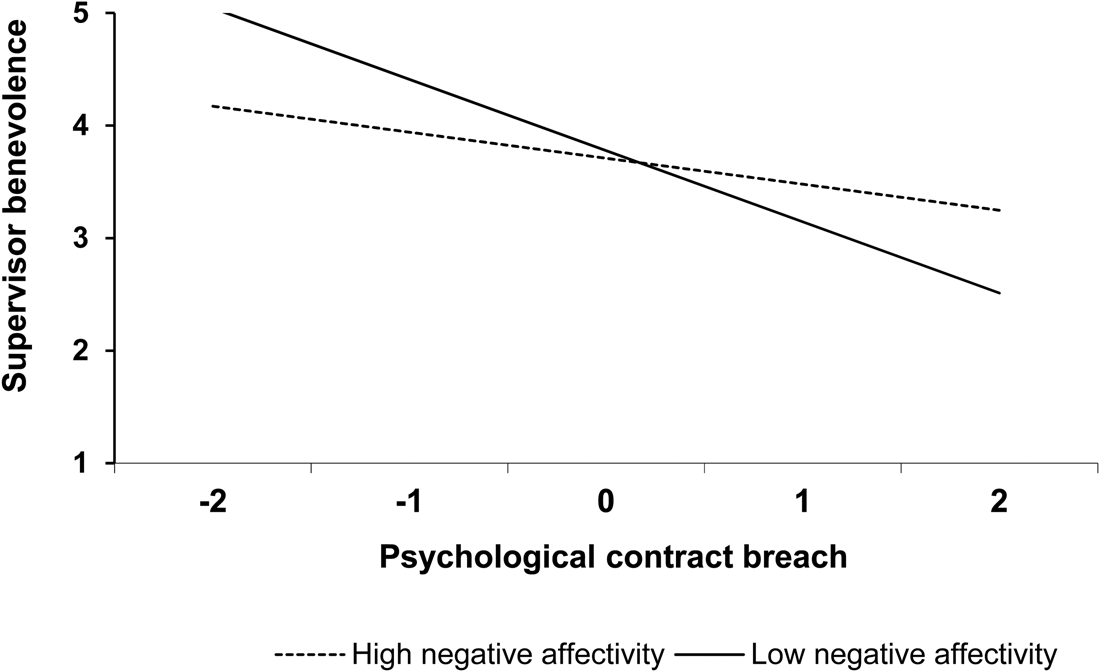

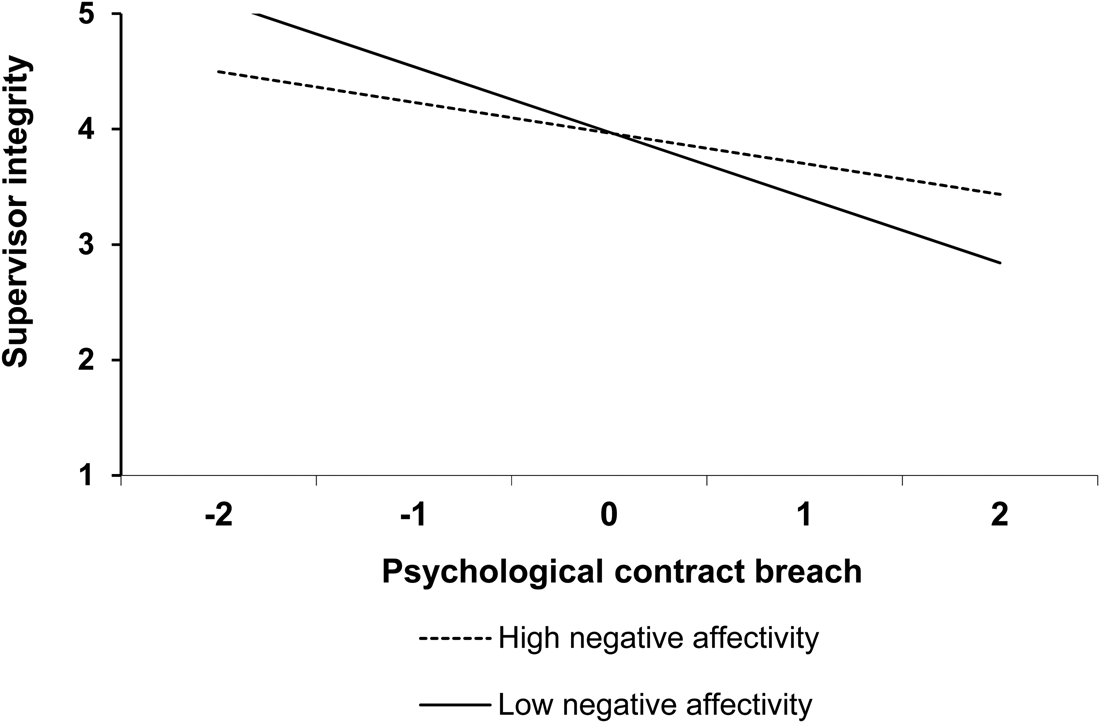

We used moderated multiple regression to examine Hypotheses 3a–c. Following Aiken and West (Reference Aiken and West1991), Aguinis and Gottfredson (Reference Aguinis and Gottfredson2010), and Jaccard and Turrisi (Reference Jaccard and Turrisi2003), contract breach and negative affectivity were centered prior to the calculation of their interaction term. Results reported in Table 2 (Model 3s) show that contract breach and negative affectivity interacted in the prediction of supervisor ability (β = .22, p < .001, ΔR 2 = .05), benevolence (β = .26, p < .001, ΔR 2 = .06), and integrity (β = .21, p < .001, ΔR 2 = .05). To illustrate these interactions (Aguinis & Gottfredson, Reference Aguinis and Gottfredson2010), we plotted the regression line of trustworthiness dimensions on contract breach at 1 SD below and 1 SD above the mean of negative affectivity (see Figures 2–4). Simple slope analyses showed that contract breach was significantly and negatively related to supervisor ability, benevolence, and integrity at both high (t [232] = –2.03, p < .001, t [232] = –3.81, p < .001, and t [232] = –4.60, p < .001, respectively) and low (t [232] = –7.05, p < .001, t [232] = –10.44, p < .001, and t [232] = –9.80, p < .001, respectively) levels of negative affectivity. However, these relationships were significantly weaker at high levels of negative affectivity (t [232] = 3.72, p < .05, t [232] = 4.91, p < .05, and t [232] = 4.11, p < .001, respectively). Therefore, Hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 3c are supported.

Figure 2. Interaction between psychological contract breach and negative affectivity in predicting supervisor ability.

Figure 3. Interaction between psychological contract breach and negative affectivity in predicting supervisor benevolence.

Figure 4. Interaction between psychological contract breach and negative affectivity in predicting supervisor integrity.

Hypotheses 4a–b

We followed Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes's (Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007; see also Hayes, Reference Hayes2015) moderated mediation analytical procedure to examine Hypotheses 4a–b. Negative affectivity did not moderate the indirect effect of contract breach on voluntary turnover through supervisor benevolence (–.13, 95% CI –.43 to .05), this indirect effect being non-significant at both high (.09, 95% CI –.04 to .28) and low (.24, 95% CI –.11 to .66) levels of negative affectivity. Hypothesis 4a is thus not supported. In contrast, the indirect effect of contract breach on voluntary turnover through supervisor integrity was significantly moderated by negative affectivity (–.18, 95% CI –.46 to –.02), this indirect effect being weaker at high (.18, 95% CI .01 to .47) than at low (.38, 95% CI .002 to .77) levels of negative affectivity. Hypothesis 4b is thus supported.Footnote 1

Discussion

Aiming to offer new insights into the psychological contract breach–voluntary turnover relationship, this study found a negative relationship between contract breach and the three dimensions of supervisor trustworthiness, i.e., ability, benevolence, and integrity, and further demonstrated that contract breach was positively related to voluntary turnover through lower supervisor integrity. In addition, these relationships were found to be weaker at high levels of negative affectivity. These findings bear important implications for theory and practice which are outlined below.

Theoretical implications and directions for future research

First, our study suggests that psychological contract breach is likely to undermine newcomers' perception that they can count on their supervisor's ability, benevolence, and integrity. Consistent with an attributional perspective, these negative relationships suggest that newcomers attribute, at least in part, breaches to a lack of trustworthiness on the part of the supervisor. As such, results reinforce the key role played by supervisors in the breach process (Ng, Feldman, & Butts, Reference Ng, Feldman and Butts2014). Besides, just as breach is a subjective phenomenon (Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997; Robinson, Reference Robinson1996), judgments of trustworthiness reflect subjective impressions (Rule et al., Reference Rule, Krendl, Ivcevic and Ambady2013). Considering this and as individuals may attribute different causes to breach depending on their past experiences (Kelley & Michela, Reference Kelley and Michela1980), an interesting extension to this study would be to assess how newcomers' history of breaches with former employers affects the attributions they make following breaches to the psychological contract, and the role they see supervisors playing in the breach process (Robinson & Morrison, Reference Robinson and Morrison2000).

Second, this study identified supervisor integrity as a key mediator of the breach–voluntary turnover relationship. This finding suggests that a lack of integrity of the supervisor is interpreted by newcomers as a voluntary contribution to breach (Lester et al., Reference Lester, Turnley, Bloodgood and Bolino2002; Morrison & Robinson, Reference Morrison and Robinson1997). Such attribute of the supervisor would mean that he or she has knowingly broken the psychological contract, and, as this is perceived as a form of betrayal (Elangovan & Shapiro, Reference Elangovan and Shapiro1998), it makes newcomers more inclined to leave the organization. Furthermore, newcomers who come to think that their supervisor's words and actions are inconsistent or unpredictable (i.e., low integrity) probably experience heightened uncertainty and more readily question the value of maintaining organizational membership following breach events. Considering that reducing uncertainty is a major driver of newcomers' behavior, such experiences likely lead to premature voluntary turnover (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Bodner, Erdogan, Truxillo and Tucker2007).

In contrast, we did not find support for a mediating effect of supervisor benevolence. It might be that the assessment of supervisor's benevolence, because it is mainly established through repeated interactions (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995), takes more time to develop and show effects on outcome variables. Therefore, newcomers who do not feel cared about by their supervisor (i.e., benevolence) may not feel threatened and would not question their organizational membership in the short-term, which would explain the absence of a relationship between supervisor benevolence and voluntary turnover in this study. On the contrary, in the course of organizational socialization, newcomers are likely to indirectly learn more about supervisors' integrity (e.g., through informal networks; Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, Reference Mayer, Davis and Schoorman1995), which is consistent with the significant relationship between integrity and voluntary turnover. In this regard, our study also emphasizes the importance of distinguishing the three trustworthiness dimensions (Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, Reference Colquitt, Scott and LePine2007; Legood, Thomas, & Sacramento, Reference Legood, Thomas and Sacramento2016; see also Weiss, Michels, Burgmer, Mussweiler, Ockenfels, & Hofmann, Reference Weiss, Michels, Burgmer, Mussweiler, Ockenfels and Hofmann2020). As a future study, it would be worth testing the mediating effect of supervisor integrity in samples of regular employees, as it is unclear whether and how relationship duration influences the results (Dirks & Ferrin, Reference Dirks and Ferrin2002; Frazier, Tupper, & Fainshmidt, Reference Frazier, Tupper and Fainshmidt2016; Pate, Morgan-Thomas, & Beaumont, Reference Pate, Morgan-Thomas and Beaumont2012).

Third, the moderating effect of negative affectivity found in this study is consistent with the premise that individuals with high levels of negative affectivity, as they tend to get prepared for negative fallouts (Begley & Lee, Reference Begley and Lee2005; Judge & Larsen, Reference Judge and Larsen2001), are less reactive to negative events compared to individuals with low negative affectivity. In doing so, this study helps clarify the role of trait affect in attributional processes (Douglas & Martinko, Reference Douglas and Martinko2001). Specifically, high-negative affectivity newcomers were found to be less inclined to attribute breaches to a lack of supervisor trustworthiness and less likely to leave as a result. This reverse-buffering effect is consistent with a met expectations account of negative affectivity's workings (Wanous et al., Reference Wanous, Poland, Premack and Davis1992). Indeed, high-negative affectivity individuals do not have their expectations violated when they experience contract breaches, hence react less negatively to these events. Note however that although they are less likely to act following a negative event (e.g., Lopina, Rogelberg, & Howell, Reference Lopina, Rogelberg and Howell2012), these individuals are not necessarily committed to their organization or less likely to think about quitting (Cropanzano, James, & Konovsky, Reference Cropanzano, James and Konovsky1993). Given this, future studies should examine the multiple mechanisms through which negative affectivity intervenes in the withdrawal process.

Although our findings are consistent with a met expectations interpretation of negative affectivity's effects, other research has suggested that ‘negative affectivity may act as a vulnerability factor’ (Lazuras, Rodafinos, Matsiggos, & Stamatoulakis, Reference Lazuras, Rodafinos, Matsiggos and Stamatoulakis2009: 1076). That is, high-negative affectivity individuals may perceive job stressors (e.g., psychological contract breach) more intensely and subsequently develop more negative reactions to stress (Spector, Zapf, Chen, & Frese, Reference Spector, Zapf, Chen and Frese2000; see also Penney & Spector, Reference Penney and Spector2005; Walker, Van Jaarsveld, & Skarlicki, Reference Walker, Van Jaarsveld and Skarlicki2014). Meta-analytic reviews have indeed reported negative affectivity to be positively related to strain and other stress responses (Alarcon, Eschleman, & Bowling, Reference Alarcon, Eschleman and Bowling2009; Ng & Sorensen, Reference Ng and Sorensen2009). Yet, our results do not support the idea that negative affectivity would act as a vulnerability factor in the context of the relationship between contract breach and supervisor trustworthiness. Indeed, the correlation between negative affectivity and contract breach was rather weak in absolute terms (r = .12, p < .05; see Table 1) and the effects of negative affectivity on supervisor trustworthiness dimensions were non-significant (see Table 2). This may be because perceptions of supervisor trustworthiness are more cognitive in nature and do not represent stress reactions per se. Such perceptions may be more influenced by the extent to which contract breach comes as a surprise in the eyes of employees. Further research is required to elucidate this question.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, although the variety of occupations represented in our sample is desirable for generalization purposes, we do not know if participants were representative of the organization/association they belonged to. Second, even if our 1-year or less of tenure criterion was similar to previous studies (see Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Bodner, Erdogan, Truxillo and Tucker2007), the time period during which someone is a ‘newcomer’ is probably variable and context-specific. Third, sample attrition between measurement times was not entirely random. Newcomers experiencing low psychological contract breach were more likely to drop from the study. This may be due to individuals experiencing high levels of breach leaving their organization sooner, making our study rather conservative regarding the effects of breach. Fourth, all variables except voluntary turnover were measured at the same point in time, which raises common method variance concerns. However, tests of interaction effects, such as those involving negative affectivity, are not positively biased by method variance (Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, Reference Siemsen, Roth and Oliveira2010). Fifth, the fact that data on psychological contract breach and supervisor trustworthiness were collected at the same time limits our ability to draw causal inferences. Although the theoretical framework used in this study suggests the opposite, it remains possible for supervisor trustworthiness to influence psychological contract breach, rather than the reverse. More sophisticated longitudinal designs would be required in the future to palliate to this limitation and draw firmer conclusions about the direction of the relationships between the study's variables.

Sixth, trustworthiness dimensions were highly correlated (rs = .57‒.80). However, this study's results indicate that these dimensions were distinguishable and not interchangeable predictors of voluntary turnover. Moreover, there is reason to distinguish these dimensions from a theoretical perspective because they evoke distinct attributions regarding the role played by supervisors in breach events. Finally, it should be noted that, as the study was conducted among a sample of Canadian newcomers recruited via the organization or association they belonged to, it is unclear whether the results would generalize across samples and settings. We invite researchers to seek to replicate this study's findings in different cultural contexts (e.g., China; Lo & Aryee, Reference Lo and Aryee2003) and industries (e.g., the public sector; Welander, Blomberg, & Isaksson, Reference Welander, Blomberg and Isaksson2020) to examine their generalizability.

Practical implications

This study's findings recall that supervisors should examine the promises they have knowingly or unknowingly conveyed to newcomers and try to fulfill these as much as possible (Morsch, Dijk, & Kodden, Reference Morsch, Dijk and Kodden2020; Solberg, Lapointe, & Dysvik, Reference Solberg, Lapointe and Dysvik2020; Welander, Blomberg, & Isaksson, Reference Welander, Blomberg and Isaksson2020; Woodrow & Guest, Reference Woodrow and Guest2020). Since supervisor integrity is particularly critical, policies to encourage the integrity of supervisors and training activities supporting the enactment of fair and ethical human resource practices seem warranted (Byrne, Pitts, Chiaburu, & Steiner, Reference Byrne, Pitts, Chiaburu and Steiner2011; Pate, Morgan-Thomas, & Beaumont, Reference Pate, Morgan-Thomas and Beaumont2012; see also Breuer, Hüffmeier, Hibben, & Hertel, Reference Breuer, Hüffmeier, Hibben and Hertel2020; Holtz et al., Reference Holtz, De Cremer, Hu, Kim and Giacalone2020; Nedkovski, Guerci, De Battisti, & Siletti, Reference Nedkovski, Guerci, De Battisti and Siletti2017). The establishment of effective communication channels and practices fostering supervisor–subordinate interactions could also help to avoid false impressions of low integrity (Rule et al., Reference Rule, Krendl, Ivcevic and Ambady2013; see also Holtz et al., Reference Holtz, De Cremer, Hu, Kim and Giacalone2020). Regarding the influence of negative affectivity, Holtom, Burton, and Crossley (Reference Holtom, Burton and Crossley2012) state that individual dispositions inform how supervisors might interact with specific employees. Supervisors should try to anticipate and, where appropriate, strategically manage the interpretation of certain events to maintain positive attitudes among employees. Supervisors may also seek to involve high-negative affectivity newcomers in developing solutions to potential contract breaches in order to make them, not just employees that stay in the organization, but good organizational citizens (Holtom, Burton, & Crossley, Reference Holtom, Burton and Crossley2012).

Émilie Lapointe is an Associate Professor in the Department of Leadership and Organizational Behavior, BI Norwegian Business School. Her current research is in the areas of organizational socialization, employee–supervisor relationships, employee–organization relationships, and international organizational behavior and human resource management. She has published academic articles in journals such as Human Relations, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, and International Journal of Human Resource Management, and international conference papers.

Christian Vandenberghe is a Professor of Organizational Behavior at HEC Montreal and holder of the Research Chair in the management of employee commitment and performance. His research interests include organizational commitment, turnover and performance, and attitude change. His work has been published in a variety of journals, including Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Management, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Human Relations, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Human Resource Management, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Journal of Vocational Behavior, and Group & Organization Management.