The Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 was implemented in October 2005. It introduced some changes to the process and principles of detaining patients in Scotland. The Act underlined ten principles which must guide everybody involved in the Act, including non-discrimination, equality, respect for diversity and reciprocity. Informal care should be used whenever possible and the patient's and carers’ past, present and future wishes should be considered. There must be respect for carers and child welfare. The least restrictive options should be used and the benefit to the service user must be demonstrable.

Prior to October 2005 the gateway section to hospital treatment was section 24 or 25 of the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984. This section could be completed by any registered medical practitioner and allowed for detention for up to 72 h without leave to appeal. It was hoped with the introduction of the new Act that the gateway section would be a 28-day section (section 44). This section requires the doctor applying for the section to be approved under section 22 of the Act as having special experience in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorder. With leave to appeal to a tribunal, much as in the English and Welsh systems, this section requires the consent of a mental health officer; family members can no longer consent. A new treatment option was introduced to allow compulsory treatment in the community.

In this study we audited the admissions to the general adult psychiatry wards in the Perth and Kinross area of Tayside prior to and after the introduction of the new Act to assess the impact of the change in mental health legislation.

Method

The study took place from December 2004 to July 2005 (sample 1) and then December 2005 to July 2006 (sample 2). The new Act came into force on 5 October 2005, which gave 2 months to allow some of the immediate problems to be resolved. The same months were chosen to reduce seasonal variations. The patients were admitted to the two single-gender wards in Murray Royal Hospital, Perth; the wards have 24 beds each and are open wards. The total population of the catchment area was 135 000. All admissions to the unit were included in the audit retrospectively.

A case-note review was undertaken. Simple demographic details were collected via a specially designed pro forma (available from authors on request). The admission and discharge diagnoses were recorded. The legal status on admission and discharge was collected and the patient's length of stay in hospital calculated. The number of days the patient remained under the Act was calculated for each admission.

The data were analysed using t-tests for continuous data and χ 2-tests for discrete variables.

Results

Sample 1 comprised 195 patients, but notes were missing for 15 patients leaving 180 for study analysis. Sample 2 comprised 176 patients, with 25 missing notes leaving 151 for analysis. In total data were missing for 10.8%.

Analysis of the combined sample

In the combined sample, 58.9% of patients were male and 41.9% were female. The mean age for the total population was 39.6 years (s.d.=11.4 years).

Most of the patients were admitted informally (71.9%). In the combined sample significantly more male patients were detained than female patients (P=0.01), but there was no significant difference in the mean age or previous number of admissions. Patients who were detained had symptoms at a significantly earlier age (24.97 years) compared with informal patients (30.27 years) (P=0.001).

Detained patients stayed in hospital much longer on average. The mean length of stay for informal patients was 15.9 days v. 63 days for detained patients (P<0.001). More patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were detained (P=0.001) than those with depression or primary substance misuse.

Detentions before and after the change in Act

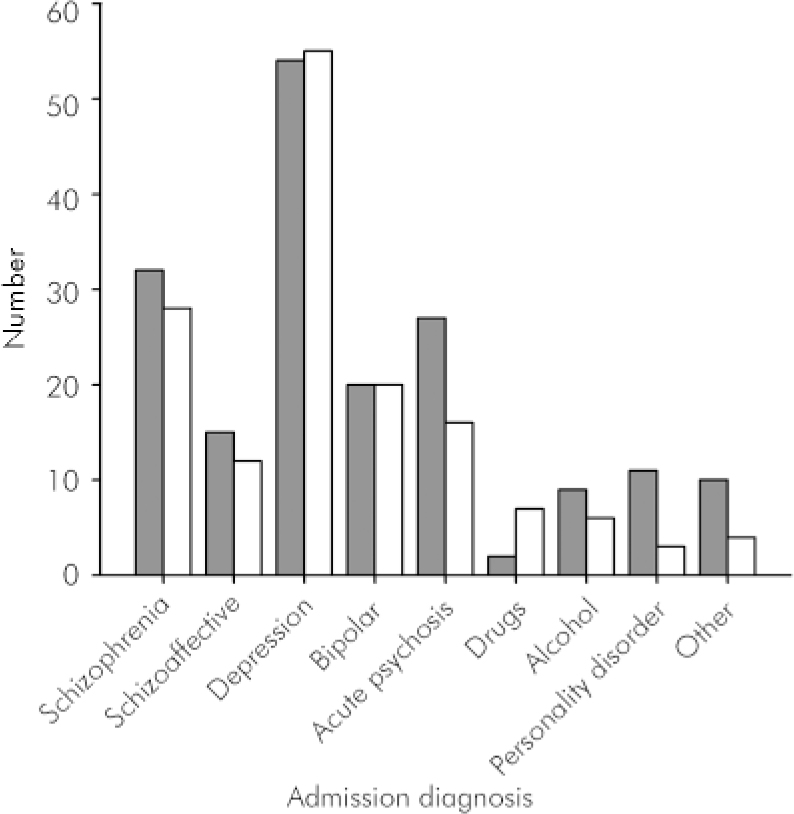

There were no differences in the populations admitted before and after the change of legislation in terms of gender, age, age at first symptoms or mean length of stay. Patients admitted before the Act changed did have significantly more previous admissions (P=0.001). The admission diagnoses are shown in Fig. 1. The diagnoses of those patients detained before and after the change did not differ.

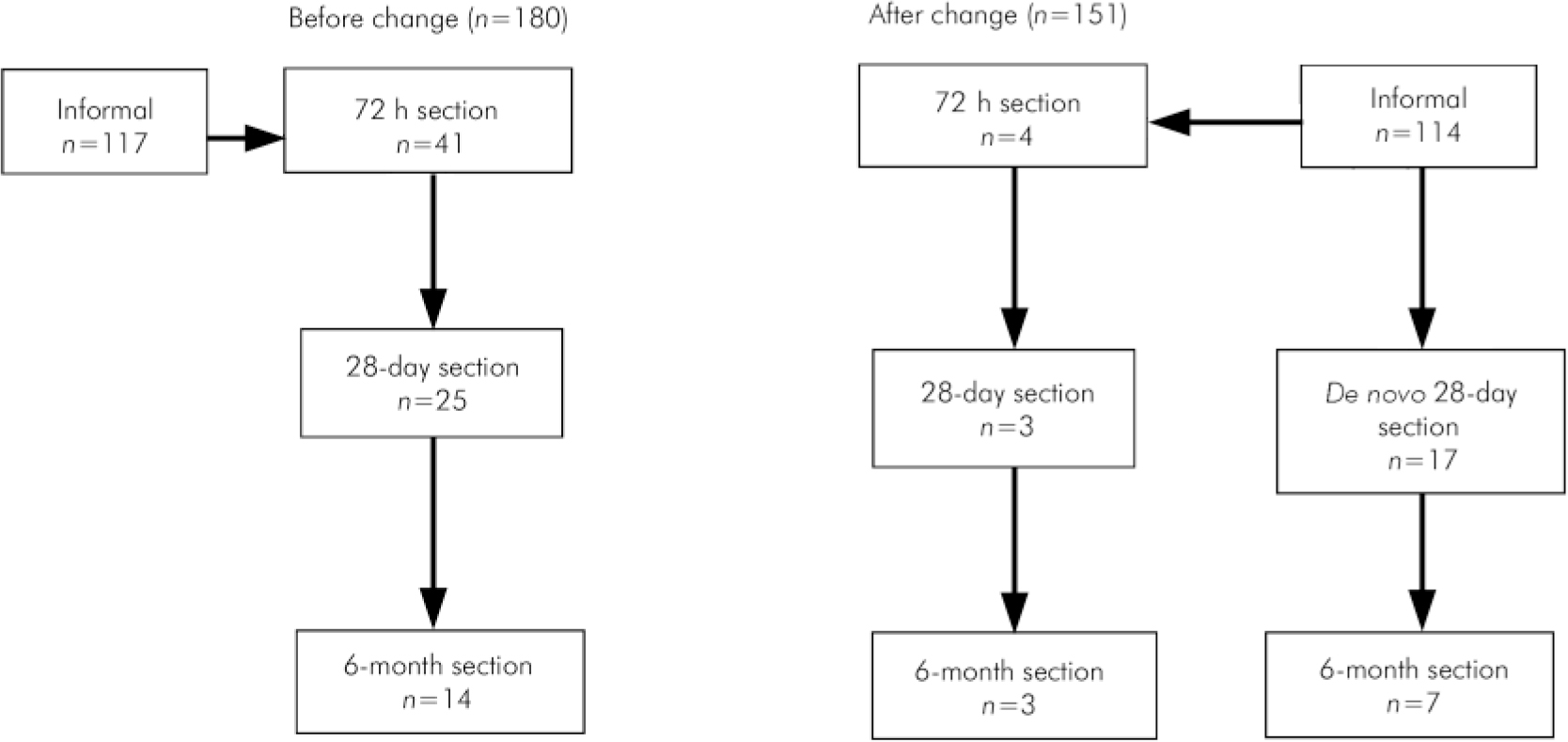

The legal status at admission of the two samples is shown in Table 1. Very few patients were detained under emergency (72 h) sections after the Act was introduced. The main gateway section was section 44 which requires an opinion by a section 22 approved doctor. Before the Act changed 36% of patients admitted were detained, afterwards this reduced to 25.7%. The progression of the various sections is shown in Fig. 2. Only 41% of patients admitted under the new gateway section progressed to further detention compared with 61% previously. Significantly more people were detained before the change in the Act (P=0.05), but there was no significant change in the number of people progressing to longer-term sections.

Table 1. Legal status of patients on admission

| Legal status | Sample 1 n (%) | Sample 2 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 72 h section | 41 (22.7) | 4 (2.6) |

| 28-day section | 0 (0) | 17 (9.4) |

| 6-month section | 16 (8.8) | 9 (6.5) |

| Criminal procedures | 6 (3.3) | 3 (2.0) |

| Informal | 117 (65.0) | 114 (75.5) |

Fig. 1. Admission diagnosis of patients admitted to the general adult psychiatric wards before and after the change in mental health legislation. ▪, before change; □, after change.

Fig. 2. Progression of sections before and after the change in legislation.

The average length of stay of detained patients before and after the introduction of the new Act is shown in Table 2. Although the mean length of detention for patients seems to be decreasing, it has increased for patients under the short-term section.

Table 2. Mean length of stay for detained and informal patients

| Type of section | Sample 1, days | Sample 2, days |

|---|---|---|

| Informal | 15.33 | 16.7 |

| Detained | 59.90* | 53.50* |

| Total | 32.27 | 28.02 |

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that fewer patients are being detained de novo than previously. This could be due to a threshold effect, as section 22 approved doctors (specialist registrars and consultants) as opposed to general medical practitioners are involved in making the decision regarding detainability. There were no differences in the diagnoses of patients detained before or after the implementation of the new Act. Patients were more likely to have their detentions extended but spent a shorter time in hospital, possibly because of the use of community-based compulsory treatment orders.

Under the old Act the Tayside area had one of the highest rates of use of emergency and short-term detentions (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, 2005). Tayside had between 100 and 120 detentions per 100 000 population compared with 60 per 100 000 in the Borders area. When the rates of application for 6-month sections under the old Act are examined, Perth and Kinross was third in the table, above the urban centres of Glasgow and Edinburgh (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, 2005). This has been a long-standing finding and no satisfactory explanation has ever been produced. However, after October 2005 Tayside no longer appeared to use the mental health legislation more than other areas.

The rate of progression to a longer-term detention under the new Act in Tayside was overall 46.7%. This compares favourably with the results produced by the Mental Health Tribunal for Scotland (2006a , b ). During the period of January to June 2006 the rate of progression in various health boards varied between 41.5 and 52.3%.

The introduction of the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 appears to have achieved in a relatively short period the aspirations of the Millan report (Scottish Executive, 2001). There has been increased scrutiny by more experienced practitioners before patients are deprived of their liberty in hospital. This has led to an increase in the amount of consultant time devoted to form-filling and attending tribunals which is placing added demands on services. There has been reduced variability in the geographical application of mental health legislation. The length of time that patients spend in hospital under detention has also been reduced, and this is in keeping with the principles of the Act to use the least restrictive option for treatment. The availability of community-based compulsory treatment orders may have contributed to this. It remains to be seen what long-term effects the introduction of the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 will have on patient care.

Declaration of interest

T.W. is a medical member of the Mental Health Tribunal for Scotland.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.