1. INTRODUCTION

Suppose Alice has decided to buy a new t-shirt. While shopping, she finds two stores selling t-shirts she likes. The shirts on offer are identical in their physical appearance, but differ significantly in their production history. The first store belongs to a brand whose entire production takes place in the US. Labelling its products as ‘sweatshop free’, the company prides itself on the fact that the workers producing its garments work under conditions that meet US health and safety standards and earn what, according to the company’s marketing, is a ‘fair wage’. The second store, in contrast, belongs to a retail clothing brand whose products are manufactured in Bangladesh, in factories that have been described as typical of ‘sweatshops’. Garment workers in these factories are exposed to significant health and safety risks and are employed at wages that have been widely criticized as unfairly low.

In addition to the difference in production history and, at least in part, as a reflection of it, the t-shirts also differ in their retail price. While the ‘fairly produced’ t-shirt has a price of $20, the ‘conventional’ t-shirt is being sold for $5. Both of these prices are within the limits of what Alice is generally prepared to pay – that is, we will assume Alice’s reservation price for a new shirt is at least $20. Of course, like other consumers, Alice has a ceteris paribus preference to pay less rather than more for her new t-shirt. At the same time, however, Alice is motivated to take into account moral considerations in deciding which shirt to buy. But how are the options available to Alice to be evaluated from a moral point of view? Assuming that Alice is going to purchase one or the other of the two products just described, what is the morally best course of action for her to pursue?

In this paper, we consider three salient responses to the choice faced by Alice and assess the normative force of these responses in different economic contexts. Section 2 introduces the three options, which we call the compensatory, instinctive and dismissive options and provides a rationale for thinking that the compensatory option is morally superior to the other alternatives. In Section 3, we consider four questions that have some bearing on which option is morally best. In Section 4, we consider the scope of Alice’s obligations as a consumer, the rights of workers, and discuss the implementation of the compensatory option. Finally, Section 5 concludes.

2. THREE OPTIONS

According to a common response, it is morally best for Alice to purchase the fairly produced t-shirt made in the US. Sweatshops, on this view, are morally objectionable because the wages paid to those who work in them are unfairly low. By purchasing the t-shirt made in the US, Alice avoids relying on the sweatshop labour used in Bangladesh to produce the conventional t-shirt and ensures that the workers who produced the shirt she buys have been fairly compensated. Call this course of action the ‘instinctive option’.

Some philosophers and many economists have dismissed this response, arguing that the case for the instinctive option fails to give adequate weight to the welfare interests of sweatshop workers (Krugman 2016). More specifically, opponents have pointed out that ‘sweatshop labor often represents the best option available for desperately poor workers to improve their lives and the lives of their family’ (Powell and Zwolinski Reference Powell and Zwolinski2011: 449). Empirical data support this assessment. To take a particular example, in 2000, annual per capita income in Nicaragua was ‘about $470’, yet at that time, garment workers at Chentex [a subcontracted garment firm] could earn between $700 and $900 per year, a significant difference in income that generated high demand for sweatshop jobs (Ross Reference Ross2004: 117). On a broader scale, the shift of manufacturing jobs from high income countries to developing and lower income countries has significantly reduced global poverty. For example, between 2010 and 2015, Chinese per capita disposable income increased 182% in rural regions and 166% in urban areas.Footnote 1 These considerations provide a basis for a second response, namely, that it is morally best for Alice to purchase the conventional t-shirt. Assuming that sweatshop wages are indeed unfair, this option, unlike the instinctive option, will fail to ensure that the workers who produced Alice’s t-shirt have been remunerated fairly. (As we discuss later, proponents of this option may question the assumption of unfair wages.) This, however, does not affect the rationale for this option which concerns the welfare effects associated with Alice’s choice. In particular, defenders of this option rely on the assumption that demand for the conventional t-shirt contributes to the availability of sweatshop jobs in Bangladesh. Workers there stand to gain a significantly greater amount of welfare from these jobs, compared to their next best option, and to be significantly worse off without them compared to the American garment workers manufacturing the fairly produced t-shirt. Furthermore, in addition to the immediate welfare gains for individual workers, the growth of the manufacturing sector in developing countries can have important economic ‘ripple effects’ leading to more widespread welfare gains across society. Call the purchase of the conventional t-shirt the ‘dismissive option’.

The justifications of these two responses appeal to two values that are opposed in Alice’s options. The first is a concern for fairness with regard to the remuneration of the workers that produced the t-shirts. The second is a concern for the welfare effects of Alice’s decision. Fairness and welfare both represent important values. Moral theories that place an absolute weight on either generate implausible prescriptions for many cases. Those that give some weight to each value nevertheless remain contentious, in part because they must justify these weights. Insofar as, along the lines just described, the choice between the instinctive and the dismissive options involves a trade-off between fairness and welfare, determining whether the instinctive option is morally better than the dismissive option, or vice versa, would require taking a position on the weighing of these two important values. There is a third course of action, however, that does not require taking a position on the relative importance of fairness and welfare. Like the instinctive option, this third option provides a way to ensure that the workers who produce Alice’s t-shirt receive a fair level of remuneration while also supporting the welfare-based considerations that provide the rationale for the dismissive response.

Choosing what we call the ‘compensatory option’, Alice could purchase the conventional t-shirt and, through separate channels, provide a monetary transfer to the workers involved in the production of the t-shirt that compensates them for the difference between their actual wage and a fair wage for the relevant unit of production. We call this difference δ. The transfer of δ would ensure that the concern for fairness that motivates the instinctive response is satisfied. At the same time, this course of action would send the same signal of demand for garment products made in Bangladesh as the dismissive option and would provide greater welfare to workers who are relatively poor than the dismissive option. It is thus weakly superior to the dismissive option in terms of its welfare effects.

There are, of course, further options available to Alice that are conceivable in this example. However, the dismissive and instinctive options represent the most salient actions for most consumers. Most consumers will either purchase one shirt or the other. The compensatory option provides a straightforward alternative within the domain of consumer behaviour that is, at least prima facie, morally superior to the two alternatives. However, the plausibility of its moral superiority depends on a number of assumptions, which we examine in the following section.

3. FOUR OBJECTIONS

Here we consider four threats to the claim that the compensatory option is morally better than the other alternatives: are sweatshop wages really unfair, can the transfer of δ fully compensate workers for the wrongs they experience in sweatshops, does the transfer of δ undermine existing wage levels, and finally, would the pursuit of the instinctive option as a form of boycott be more successful?

3.1. Are sweatshop wages unfair?

Advocates of the dismissive option may defend their position by challenging the assumption that the sweatshop wages in our scenario are unfair. If the wages were fair, then δ – the difference between the actual wage and the fair wage – would be $0 and the compensatory option would not represent a distinct course of action.Footnote 2 The purchase of the t-shirt made in Bangladesh and the purchase of the t-shirt made in the US would be equivalent in terms of fairness, but welfare-based considerations would seem to speak in favour of purchasing the t-shirt made in Bangladesh.

Our description of Alice’s choice is meant to represent a fictitious case, albeit one that does not depart too far from reality. Whether wages paid by existing sweatshops are unfair depends on the empirical facts that characterize individual cases and on the criterion that is assumed to determine whether a given wage is fair. Without wishing to defend any specific empirical claims about existing firms, we think that, insofar as there are theoretically sound fairness criteria, it is likely that some factories violate these criteria, while others may comply with them, as stipulated by the description of the Bangladesh and US based factories in our scenario. The more fundamental issue is whether there are plausible accounts of fairness that apply in the context of wage labour.

Transactions are bilateral exchanges in which cooperative behaviour generates a utility surplus to be distributed between the transactors, where utility is a measure of the transactors’ preferences. Suppose Alice wants Bob to clear snow from her property and Bob wants Alice’s money in exchange. The more Alice pays Bob, the less utility she receives and, at her reservation price (say $20) she gains no net utility from the shovelling. The less money Bob gets for the work, the less utility he receives. At his reservation price (say $10) he gains no net utility from the transaction. These price points define the range of mutually beneficial transactions that are possible between Alice and Bob. The set of all mutually beneficial transactions is called the contract curve.

The notion of fairness implicit in the instinctive response is one of distributive fairness. If a transaction is distributively unfair, then there must be some distribuendum that is maldistributed and a distributive criterion that specifies how the distribuendum should be distributed. We argue that any plausible account of fair transactions should employ a distribuendum and distributive criterion that pick out a fair price that lies on the contract curve. Suppose a particular theory picks out a fair price that lies off the curve – perhaps a fair price for Bob’s shovelling is $25. Since $20 is the most Alice is willing to pay, the transaction will not occur. This outcome is worse for both parties since there are a number of transactions (all on the contract curve) that both prefer to not transacting. Were Alice to pay Bob $25, the transaction would cease to be a mutually beneficial transaction and instead would be a form of exchange that makes Alice worse off and Bob better off (in terms of preference satisfaction) than the status quo. By locating the ‘fair’ price off the contract curve a theory would not provide an account of how a jointly generated surplus should be distributed, instead requiring a transfer to Bob at a net loss to Alice.

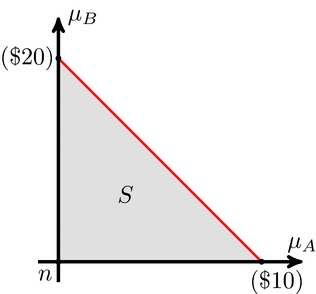

Figure 1. Alice and Bob’s bargaining problem.

Limiting candidates for a fair price to prices on the contract curve excludes many proposed accounts of fair transactions. For example, basic needs approaches claim that transactions are unfair if they fail to ensure that the parties’ basic needs are met (Sample Reference Sample2003; Snyder Reference Snyder2008). However, if the terms that would ensure the transactors’ basic needs are met lie beyond one transactor’s reservation price, then a fair transaction is infeasible (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2016). The same problem confronts accounts that conceive of fair prices in terms of costs of production, for example (Reiff Reference Reiff2013).

One approach to conceiving of fair transactions that respects the contract curve constraint is to model transactions as two person cooperative games, or bargaining problems. Bargaining problems are characterized by each agent’s status quo utility (n); the agents’ utility functions, which define a set S of Pareto improving points; and a solution concept, a function mapping the feasible set and status quo to a point in S. Figure I below models the snow shovelling case as a bargaining problem (assuming linear utilities, for the sake of simplicity) where Alice’s utility is on the horizontal axis, Bob’s is on the vertical axis, and n is the utility each receives if no transaction occurs. We know that Alice’s reservation price is $20 and Bob’s is $10. Thus, S is bounded by n and the utility each receives at these prices. The red frontier represents the contract curve.

There is a large literature of proposed solutions to bargaining problems between rational agents. The most prominent ones include the Nash (Reference Nash1950) solution, the Kalai and Smorodinsky (Reference Kalai and Smorodinsky1975) solution and the egalitarian solution (Kalai Reference Kalai1977). When interpreted as criteria of fair division, these solution concepts provide substantive accounts of fair transaction. According to these substantive accounts, whether a price is fair depends on whether it conforms to a particular bargaining outcome stipulated by a distribution criterion. For example, the egalitarian criterion claims that a transaction is fair when the minimum gains of both parties are maximized ($15 in the example above).

The substantive approach can be contrasted with procedural accounts that claim that any outcome can be fair, provided the way the outcome is reached is consistent with certain procedural conditions (Zwolinski and Wertheimer Reference Zwolinski, Wertheimer and Zalta2016). Such procedural accounts have been developed by Hillel Steiner (Reference Steiner1984, Reference Steiner and Reeve1987, Reference Steiner, Vint, Metcalfe, Kurz, Salvadori and Samuelson2010; Ferguson and Steiner Reference Ferguson, Steiner and Olsaretti2018) and John Roemer (Reference Roemer1982), for example. Steiner’s takes the form of an historical account, according to which a transaction is unfair if one party receives less and the other party more than they would have received otherwise, due to the occurrence of a prior injustice.

It is not our purpose here to provide a full account and defence of a particular theory of transactional fairness. Rather, we merely wish to point out that there are possible theories that satisfy the contract curve constraint and that may plausibly support the claim that sweatshop wages are unfair.

3.2. Can δ fully compensate sweatshops’ wrongs?

The second assumption is that the unfairness that characterizes the treatment of the workers producing the conventional t-shirt can be compensated by the transfer of δ. Our discussion so far has assumed that δ is to be conceived of as the difference between workers’ de facto wages and the wages they would receive under fair terms of employment. It may be objected that this interpretation ignores the working conditions under which the conventional t-shirt is produced.Footnote 3 Sweatshops may be bad in non-pecuniary respects. If this is so, and if pecuniary and non-pecuniary wrongs are incommensurable, then a transfer of money, via δ cannot compensate for these non-pecuniary wrongs. For example, Matt Zwolinski has argued that ‘the concept of exploitation is best understood in terms of actual or threatened rights-violation’, and that ‘the case can be made that sweatshops wrongfully exploit their workers in other [non-pecuniary] ways. Specifically, . . .various forms of psychological and/or physical abuse on the part of sweatshop managers’ (Zwolinski Reference Zwolinski2007: 710). These concerns raise two issues, the first is whether non-pecuniary and pecuniary forms of unfairness are commensurable; the second concerns the moral status of compensations for rights violations.

3.2.1. Commensurability

The existence of non-pecuniary wrongs threatens the moral superiority of the compensatory option. If the transfer of δ fails to compensate for these non-pecuniary deficiencies, there would at least be one respect in which the instinctive option was superior to the compensatory option. Let us assume that a plausible conception of fair terms of employment not only includes a certain level of wages, but, in addition, working conditions that comply with certain health and safety standards and other moral demands. If health and safety standards or other aspects of the working conditions in the factory that produces the conventional t-shirt fall short of what workers are entitled to, the transfer of δ, while making up for the shortfall in wages, would do nothing to address any of these other violations. Given that the t-shirt made in the US, by assumption, is produced under fair working conditions, it may be objected, the compensatory option would thus be inferior to the instinctive option as far as considerations of fairness in relation to the production of the t-shirt being purchased are concerned.

While this objection is initially attractive, it fundamentally turns on the question of whether violations of all kinds of workers’ entitlements can in principle be compensated through monetary transfers. If they can, the objection is easily dismissed by adjusting δ so as to include the relevant monetary amount required to compensate for any unfairness in working conditions, in addition to the amount that corrects for the shortfall in wages. This would ensure that the compensatory and the instinctive options are equivalent as far as all aspects of fairness in relation to the production of the t-shirt being purchased are concerned. If, in contrast, the working conditions in the production of the conventional t-shirt were characterized by deficiencies that are thought to be incommensurable with monetary benefits, this would indeed lead to the conclusion that the two options are not morally on a par. This conclusion would not necessarily undermine the view that the compensatory option is morally superior all things considered. Since the welfare effects associated with the compensatory option would remain unaffected, its ranking on the welfare dimension could outweigh the shortcomings as far as compensation for violations of fairness are concerned. However, determining the overall moral betterness relation between the two options would, in this case, require attaching moral weights to different values.

The issue of commensurability of working conditions and monetary benefits raises intricate questions (Ferguson Reference Ferguson, Heath, Kaldis and Marcoux2018). For example, it might be suggested that, at least when it comes to aspects of working conditions whose alteration involves costs to employers, these are best thought of as part of workers’ overall compensation package and that what matters, as far as fair terms of employment are concerned, is the monetary value of this overall package, regardless of the particular ‘mix’ of wages and working conditions that workers enjoy. Compensation for any form of unfairness through monetary transfers would be straightforward in this case. The relevant compensatory amount would simply be the difference between the actual wages plus the costs associated with actual working conditions on the one hand, and the monetary value of the overall compensation package to which workers are entitled.

In light of the possibility that large reductions in health and safety risks may come at comparatively low costs, however, the suggestion that fair terms of employment are defined by the monetary value of workers’ overall compensation package ultimately seems implausible. As an alternative, it may be suggested that at least on the condition that the mix reflected in a given compensation package is morally acceptable, any combination of monetary compensation and working conditions that falls on the same indifference curve as far as workers’ preferences are concerned should be considered morally equivalent. On this view, there would equally be no issue concerning the compensability of unfair working conditions through monetary transfers, although the cost of providing compensation for unfair working conditions may, depending on the shape of the indifference curve, differ significantly from the cost of providing fair working conditions directly.

Determining points of moral equivalence between working conditions and amounts of monetary compensation on the basis of workers’ preferences seems to have some plausibility for certain aspects of working conditions, such as the length of the working day, for example. Whether all possible combinations of working conditions and wages that lie on the same indifference curve can be considered morally equivalent, or whether there is any defensible alternative basis for trading off deficiencies in working conditions, is less clear. Extreme risks to life, for example, may be thought to be non-compensatable through monetary transfers.

Even if there are certain working conditions that are incommensurable with wages, there is at least a large range of cases in which it seems plausible to assume that full compensation could be achieved. In other cases, an all-things-considered ranking between the compensatory and the instinctive option will depend on the relative weight assigned to the avoidance of uncompensated violations of fairness in the treatment of the workers that produced Alice’s t-shirt on the one hand and the possible superiority of the welfare effects associated with the pursuit of the compensatory option.

3.2.2. Rights

There is a second worry about the ability of δ to compensate that arises even if working environments and wages are fully commensurable. Workers plausibly have rights to fair compensation packages and it seems unlikely that the violation of a right followed by compensation is morally equivalent to the non-violation of a right. For example, on most theories of rights, Alice’s right to bodily integrity not only gives her a moral claim against Bob’s hitting her without consent, it also makes it impermissible for him to do so while compensating Alice for the assault, even if the compensation leaves her as well off as she was before the assault. Similarly then, if workers have rights to particular compensation packages, the wrong of denying them these particular packages cannot be fully mitigated by the subsequent transfer of δ, even if it leaves them as well off as they would have been.Footnote 4 Despite the transfer of δ, at least within a rights-based framework, there will be a ‘moral remainder’.

The crucial question is whether this threatens our claim that the compensatory option is morally superior to either the instinctive or dismissive options. If sweatshops violate workers rights, then even if the transfer of δ leaves a moral remainder, compensation is surely morally better than non-compensation. Thus, the compensatory option remains better than the dismissive approach. Whether it is also morally superior to the instinctive approach depends on the weight of the moral remainder. If the degree to which δ mitigates the wrong of sweatshop labour is insignificant, then one might conclude that the instinctive option is morally better than the compensatory option. We think this conclusion is implausible.

First, there is at least one reason to think that the dismissive option is morally superior to the instinctive option, namely that sweatshop workers – those whose rights are being violated – would prefer Alice’s selection of the dismissive option to the instinctive option. If the dismissive option is better than the instinctive option, and the compensatory option is better than the dismissive option, then by transitivity, the compensatory option is also better than the instinctive option. Whether the dismissive option is all things considered better than the instinctive option is a position we do not wish to take a stand on here. We only note that for those who do believe it is, there is strong reason to think the moral remainder cannot undermine the superiority of the compensatory option.

There is a second reason to think that the moral remainder does not threaten the moral superiority of the compensatory option. At the point when Alice faces a choice between the three options, the violation of workers’ rights has already occurred. Although Alice is to some degree complicit in the plight of sweatshop workers (a point we discuss in Section 4), her ability as an individual consumer to stop firms from offering unfair compensation packages is limited. Given these two facts, the best she can do to remedy this wrong is to compensate workers by transferring δ.

In summary, it seems that in some cases δ cannot fully compensate for the unfairness experienced by sweatshop workers. However, the existence of a ‘moral remainder’ does not change the fact that the compensatory option is morally better than the dismissive option. And it is difficult to see how any ‘moral remainder’ left after compensating workers by δ can be sufficiently weighty to make the compensatory option less morally good than the instinctive option. The compensatory option remains the morally best course of action for consumers in most cases.

3.3. Does δ adversely affect wage levels?

Even if δ can fully compensate unfairness, the case for the compensatory option faces practical hurdles if its effect on agents’ economic incentives or firms’ responses to the transfer undermine its promised benefits. The third question is thus whether the compensatory option can actually deliver a benefit to sweatshop workers.

This question is similar to debates about minimum wage legislation, a policy option that has received a great deal of attention as a possible response to sweatshops. Yet, while similar in certain respects, the pursuit of the compensatory option differs in its implications from minimum wage legislation in important ways. Since the compensatory transfer δ is directly linked to workers’ labour, it functions as a subsidy to wages provided by the consumer. Thus δ can always reach workers regardless of firms’ behaviour.Footnote 5

Nevertheless, the transfer of δ may still affect wage rates. If workers were willing to provide labour at wage rates that did not include the transfer (call this rate ω), then they will also be willing to provide their labour if the firm reduces their contribution to workers’ take home pay to ω − δ. In such a case, the transfer would fail to provide workers with economic gains, since wages of ω − δ from the firm, plus δ from the consumer simply equal ω. If the compensatory transfer has no effect on worker income, consumers’ desire for ethically produced shirts will remain unsatisfied and they will stop making compensatory transfers. The equilibrium strategy would be for consumers to refrain from transferring δ.

However, there is an additional possibility: firms may capture a portion of δ, while allowing workers to retain some as well. The introduction of this strategy provides a new (and Pareto superior) subgame perfect equilibrium in repeated versions of the game shown below. The consumer’s choice to subsidize is represented by δ, firms’ choice to capture all of δ by A, none of δ by N, and to split ∂ by S. Let the payoffs represent proportions of δ. The payoff from splitting may take a range of values, with consumers’ proportion of δ represented by x, firms’ by 1 − x, where 0 > x > 1.

Figure 2. Subsidy capture.

Firms know that if they choose A in the first iteration (or enough early iterations) of the game, consumers will lose faith and will choose ¬δ in later iterations. Consequently, firms will not choose A. Firms also have no incentive to select N. Thus, firms will choose S. Knowing that firms will choose S, consumers will choose δ. But what value of x will firms select? If consumers cared only about the absolute value of δ that reaches workers, then the equilibrium value for x would be very low. Firms would only need to pass on more of δ than they would in consumers’ next best option, ¬δ, to make strategy S attractive. Yet, in the context of sweatshop compensation, it is plausible to assume consumers’ motivations are more nuanced.

The explicit goal of δ is to mitigate maldistributions between firms and workers. If consumers are also concerned about the proportional distribution of δ, then their threshold for x will be higher. One possibility is that consumers will only accept values of x that brings the distribution of total gains – that is the gains from employment and from δ – closer to the fair distribution. For example, suppose a fair distribution of the initial gains from employment would have been an equal distribution, but the actual distribution was a 70/30 split. Then firms’ capture of 70% or more of δ would fail to bring the distribution of total gains closer to the fair distribution. Thus, if the sole concern of consumers was that δ reduced the gap between the actual distribution of gains from employment and the distribution of gains from both that initial distribution and the transfer of δ, then consumers would only continue to provide δ when firms captured a proportion of δ that was closer to the fair distribution of initial gains than the actual distribution of initial gains was.

In practice, consumers’ motivations are likely mixed. They will care both about the proportion of δ that reaches workers and about workers’ total welfare. Repeated versions of the above game are very similar to ultimatum games. In an ultimatum game, player A offers B a particular split of a surplus which B can either accept or reject. If B accepts, both receive the payoffs proposed by A. If B rejects the offer, neither receives anything. Firms’ choice of x in the above capture game is analogous to A’s offer in an ultimatum game and consumers’ choice to either continue providing δ or stop is analogous to B’s choice to either accept or reject. A meta-analysis of studies involving ultimatum games found that, on average, A offered 40% of the gains to B and B accepted 84% of offers (Oosterbeek et al. Reference Oosterbeek, Sloof and van de Kuilen2004). Of course, the capture game differs somewhat from the ultimatum game. It is played in a more complicated context in which consumers’ interests are tied to a third party, workers; and, by paying unfair initial wages, firms have already demonstrated strong self-regarding behaviour. Nevertheless, we think it is reasonable to assume consumers’ tolerance for capture – the value of x that allows the game to continue – will be similar to values observed in ultimatum games.

This analysis assumes that a significant number of consumers choose the compensatory option. If Alice alone made a compensatory transfer, then the firm employing the worker receiving δ would be unlikely to know she had done so – and even if they did, unlikely to attempt to capture the single instance of δ. These informational asymmetries and efficiency considerations mean that firms will not capture δ below a certain uptake threshold. The lower the expected uptake of the compensatory approach, the lower the probability that firms will capture a portion of δ and the greater the expected efficacy of each individual transfer. The upshot is that if consumer demand for fairly remunerated labour is high, and if these motivations culminate in many compensatory transfers, then firms’ capture of these transfers will undermine their effect on the relative distribution of gains between firms and workers.

High demand not only erodes the efficacy of the compensatory option, it also increases the palatability of two other actions, one performed by firms, the other by consumers. First, if consumer demand for such goods is indeed high, then firms would have an incentive to increase wages, advertise this increase and pass the price of the wage hike on to consumers while also increasing profits by retaining a portion of these price increases.Footnote 6 If ‘ethical’ consumers are sufficiently price insensitive, firms may be able to profit more from this strategy than they would from subsidy capture. Second, if demand is high, consumers have an incentive to select the instinctive option as a form of boycott. If a boycott succeeds, the short-term welfare loss to workers from a boycott may be offset by subsequent wages that are higher and fairer. This brings us to the final objection.

3.4. What are the prospects for a boycott?

Here we assess what we think represents the most forceful argument for the instinctive option: the claim that Alice should purchase the US-produced t-shirt in order to signal a boycott of brands whose supplier factories pay unfair wages. To boycott, in this context, is to refrain from purchasing goods from suppliers who produce goods using sweatshop labour until these suppliers change their practices. There are two important questions to ask about this approach. The first is whether the suggested boycott strategy will be effective. The second is whether it is indeed morally superior to the compensatory option.

A successful boycott, like the compensatory option, is consistent with the concern of fairness while promising not to undermine the welfare gains at stake for workers in Bangladesh. If Alice purchases the US-made t-shirt as part of a boycott of brands that rely on unfairly remunerated labour, this ensures that the workers who produced her new t-shirt were paid a fair wage. At the same time, by claiming that her action is part of a boycott she signals that if the sweatshop producer increases wages to fair levels she will purchase their product. The goal is to provide an incentive for the brand with production in Bangladesh to ensure their suppliers pay fair wages and to opt for its products in the future as soon as it does.

While a boycott is similar to the compensatory option, the two differ in two important ways. The first difference is that the success or failure of a boycott does not depend on Alice’s actions alone. While Alice can be sure that she brings about both welfare increases and unfairness mitigation through the compensatory transfer, she cannot be sure that the boycott will be successful.

The second, and related difference is that the boycott takes a high-risk, high-reward approach to welfare gains. If Alice takes part in a boycott and the boycott is successful, it will increase wages for all workers, for all clothes they produce. The welfare gains from a compensatory transfer, in contrast, will be far lower. Suppose, as an illustrative example, that a sweatshop worker currently produces 100 shirts and is paid $3 per day, but that a fair wage would be $30 per day. The difference between the actual and fair compensation per shirt, δ, would then be ![]() $\frac{\$30}{100}-\frac{\$3}{100} = \$0.27$. The compensatory option would have Alice purchase the shirt produced in the sweatshop and transfer an additional $0.27 to the worker. This mitigates unfairness and results in welfare gain, though only about one tenth of a day’s wages – and this is under the assumptions that a fair wage is as high as $30 per day (and that the worker does not produce more than 100 shirts). In reality this point is rather unlikely as the fair wage, as it almost certainly lies beyond the reservation price of the firm. The aggregate welfare gains from a successful boycott would be far greater. If the boycott succeeded in raising wages to fair levels, then all workers would receive fair wages, not only for one shirt, but in perpetuity.

$\frac{\$30}{100}-\frac{\$3}{100} = \$0.27$. The compensatory option would have Alice purchase the shirt produced in the sweatshop and transfer an additional $0.27 to the worker. This mitigates unfairness and results in welfare gain, though only about one tenth of a day’s wages – and this is under the assumptions that a fair wage is as high as $30 per day (and that the worker does not produce more than 100 shirts). In reality this point is rather unlikely as the fair wage, as it almost certainly lies beyond the reservation price of the firm. The aggregate welfare gains from a successful boycott would be far greater. If the boycott succeeded in raising wages to fair levels, then all workers would receive fair wages, not only for one shirt, but in perpetuity.

On the other hand, the risks of a boycott are also substantial. While the boycott is ongoing, consumer demand for sweatshop products is reduced. If the boycott has any hope of succeeding, this reduction must negatively affect firms’ profits, with a potential decrease in their demand for labour for the duration of the boycott. If successful, boycotts, depending on how quickly the affected brands respond to them, are likely to have some temporary negative welfare effects in the originating country (in the form of reduced demand) that will be outweighed by far greater gains down the line. But if unsuccessful, these negative effects will not be offset by greater gains. The pressing question for Alice, if she is considering the instinctive option as a form of boycott, is what is the probability that the boycott will be successful? And relatedly, what is the probability that her action will contribute to the success of a boycott?

The answer to the second question, of course, depends on who exactly ‘Alice’ is. If Alice is a prominent public figure, her purchasing habits may have a greater influence than those of the average citizen. In general, though, we should assume Alice has a standard amount of influence over the behaviour of her fellow consumers, which is to say, not a great deal of influence. If there is nothing special about Alice’s influence, then the first question is more important: what are the odds of a successful boycott?

In general, the probability of a successful boycott is not high. Numerous studies have found that the market effects of boycotts are negligible (Ashenfelter et al. Reference Ashenfelter, Ciccarella and Shatz2007; King Reference King2008, Reference King2011; McDonnell and King Reference McDonnell and King2013) and even those generally perceived to have successfully impacted their target’s financial position, such as boycotts of apartheid South Africa, had little visible effect on the financial markets (Teoh et al. Reference Teoh, Welch and Wazzan1999). In general, the reasons seem to be that while some boycotts attract a great deal of media coverage, most have neither the amount of support nor the number of committed activists that the media attention suggests. Furthermore, as King notes, ‘There’s some research that suggests that even consumers that are ideologically supportive of the boycott . . . never bought the product in the first place’ (King Reference King2016). Thus, the financial pressure that their boycotting brings is minimal. McDonnell and King (Reference McDonnell and King2013) find that boycotts can be effective in altering firms’ reputations. However, they also find that ‘many of firms’ ostensibly responsible actions and investments may actually be defensive . . . impression management tactics, rather than concessions . . . [t]he Walmarts and Nikes of the corporate world have been so frequently targeted by activists that they have developed a fairly sophisticated prosocial performance repertoire to combat those negative claims’ (McDonnell and King Reference McDonnell and King2013: 411–412).

While boycotts are not likely to be successful, they may nevertheless represent a morally attractive option when the costs of a failed boycott are sufficiently low, the benefits of a successful boycott are sufficiently high, or the probability of a successful boycott is sufficiently great. These variables simply depend on the particulars of a given case. In most cases, however, choosing the instinctive option as a means of boycott will not represent a morally compelling option when compared to the compensatory approach. This conclusion should not be taken to extend to consumer activism in general. Social and political pressure can lead to real changes in labour laws. But consumers may find effective ways to exert this pressure while still pursuing the compensatory option.

In the previous section we indicated that if consumer demand for ‘ethical’ goods was high and if it led to a significant number of compensatory transfers, then the compensatory option would be prone to capture. The studies cited above indicate that such demand is low and/or that consumers have difficulty coordinating and committing to such behaviour.Footnote 7 While this spells trouble for boycotts, it also shows that it is unlikely that enough consumers will make compensatory transfers for the kind of capture discussed in the previous section to represent a real challenge to the strategy.

4. OBLIGATION AND IMPLEMENTATION

Our primary aim is to argue that the compensatory option is morally better than the alternative options. In showing that the four main challenges to this claim fail, we have established that, in most cases, the compensatory option is morally superior to the dismissive and instinctive options. This evaluative conclusion does not imply the stronger, deontic claim that consumers are obliged to provide compensation to workers. In this section we consider whether (and why) consumers might be obliged to transfer δ to workers. In the process we will also discuss how transfers of δ could be practically implemented.

4.1. Obligations

It seems plausible that consumer obligations in the context of sweatshop labour are conditional obligations. That is, while Alice is not obliged to purchase either shirt, if she does purchase the sweatshop shirt, then she is obliged to transfer δ to workers. There is a straightforward argument supporting this obligation. When the gains from a transaction are unfairly distributed between a firm and worker to the benefit of the firm, then the firm is obliged to relinquish those gains which rightfully belong to the worker. Furthermore, no transfer of the unfair gains from the firm to a third party can be valid, since the firm itself has no valid claim to them. Should the firm transfer these gains, the third party beneficiary has an obligation to return them to the worker who has a valid claim to them. In this sense, then, if a sweatshop underpays Bob by δ and passes this on to Alice in the form of a δ reduction in the cost of clothing, Alice is obliged to return δ to the worker. Unfortunately, this straightforward explanation is threatened by three problems.

The first is that when only some of the benefits of unfairness are passed on to consumers it is unclear why they are obliged to transfer the full value of δ. Suppose the δ benefit is fully transferred to Alice. While her return of δ to Bob mitigates the harm he experiences, it does not fully rectify the wrong involved in the situation. The firm, acting as a ‘middle man’ also commits a wrong by enabling the transfer. It seems plausible that, qua ‘enablers’, firms too have some obligation to ensure the return of δ to Bob – in the same way that both the recipient of stolen goods and the thief have an obligation to return the goods to their rightful owner.

Just as firms can be complicit in enabling wrongful behaviour, so too can consumers. Even if firms retain the full δ, their ability to extract this benefit from workers depends on and occurs because of consumer purchases. And just as firms qua enablers retain an obligation to ensure the return of δ to workers even after it is transferred to consumers, so too do consumers qua enablers retain an obligation when δ is retained as profit for the firm.Footnote 8 Of course, transferring δ on their own is not the only way for consumers to discharge this obligation – they may petition the firm to return it – but given the relatively low value of δ for each consumer, making the transfer themselves is the most frictionless course of action. Thus, consumers are obliged to ensure the return of δ not only when they receive unfair benefits, but also because they are complicit in enabling firms to unfairly profit.

The second problem concerns the identification of the wronged party. If Alice cannot identify the worker that produced her shirt, then can the transfer of δ to another worker fulfil her obligation? More generally, can compensating A mitigate a wrong to B? By the ‘straightforward’ and ‘complicity’ arguments provided above, Alice’s obligation is grounded in her complicity in the firms’ extraction of unfair gains and (when she receives them) the benefits that are illegitimately passed on to her by the company. Alice’s complicity creates the conditions in which non-specific members of a group are wronged and it seems that her obligations are thus to this group. Alice can discharge her complicity-based obligation by transferring δ to any member of this group (who has not already been compensated by δ).

However, the identification problem may seem more pressing in the case of obligations grounded in the benefits Alice receives. Consider a case of theft. Suppose Bob steals $5 from Carol and gives the money to Alice. Then by the ‘straightforward’ argument, since Alice has no right to the money she is obliged to return it to Carol. Furthermore, Alice cannot discharge the obligation to Carol by giving the money to a fourth, unrelated party, Dennis. So, it appears that just as compensating Dennis does not discharge Alice’s obligation to Carol, transferring δ to another sweatshop worker does not discharge Alice’s benefit-based obligation to the worker who made her shirt.

Now consider a second case in which both Carol and Dennis leave $5 bills on a table. Bob steals both bills and gives one to Alice. While Alice knows she should return $5 to either Carol or Dennis, she does not know whose money she received. Intuitively, in this variation, if Alice returns $5 to one of the parties, then she has discharged her obligation. Yet this conflicts with the prior conclusion that if the money was Carol’s, Alice cannot discharge her obligation by giving it to Dennis. What accounts for the difference?

First, in the second case, both Carol and Dennis suffer harms. Second, these harms are identical and are the result of the same action type (but not necessarily token) that produced a benefit for Alice. Third, none of the parties knows whose money Alice received. When these features are present in a context where Alice also has a complicity-based obligation towards a particular group and in which the benefit Alice receives is derived from a fungible good, Alice can discharge her benefit-based obligation by returning the good from which she benefits to any member of the group that has been harmed by actions of the type that benefitted her.

These factors mean that Alice does not need to identify and compensate the individual who produced her shirt in order to fulfil her obligations with respect to the purchase of the sweatshop-produced t-shirt. This conclusion eases the implementation of a compensatory transfer scheme. When all members of a group are underpaid and produce the same t-shirts, Alice need only identify and compensate the relevant group to whom she is obliged, presumably the workers employed by a particular factory.

4.2. Implementation

This brings us to the final issue we consider: the practical implementation of a compensatory transfer. There exist many ways to transfer δ from the consumer to the relevant group of workers. Here we discuss two methods: direct transfer and charitable donation. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages related to the cost of transfers, identification of beneficiaries and ease of uptake.

Direct transfers, albeit rare, are increasingly possible in developing and low-income countries through the use of mobile phone banking.Footnote 9 By directly transferring δ, consumers can transform any product into a ‘fair trade analogue’ without the need for external certification and they can do so independently of the behaviour of other consumers. The direct transfer approach provides greater choice for morally motivated consumers and enjoys the greatest ease of uptake – any interested consumer can simply directly transfer δ. Challenges for the direct transfer approach include the identification of beneficiaries and the cost of the transfer. Even if, as we argued above, consumers can fulfil their obligation to workers by transferring δ to a member of a group of affected workers, consumers must have some basic understanding of who produced their clothing. In some cases, the supply chain information that is available to consumers is simply insufficient for consumers to ensure that the beneficiaries of their transfer are those to whom they have a complicity-based obligation. Nevertheless, there is some indication that the garment industry is moving towards greater supply chain transparency, in part due to pressure from advocacy groups such as Fashion Revolution, which publishes a yearly ‘Fashion Transparency Index’. A second challenge for the direct transfer approach concerns the cost of transfer. High transfer costs may undermine consumers’ willingness to provide δ, though the development of mobile and international transfer platforms such as TransferWiseFootnote 10 significantly reduces these costs.

The second form of implementation involves donating δ to a charity or NGO working with persons involved in sweatshop labour. Transfer costs to charities are low, but overhead costs vary. Some organizations apply a high rate of donations to direct programming; others have less efficient rates of conversion of donations into recipients’ benefits. Such differences are important, since what matters, from the point of view of fair compensation, is that at least δ reaches workers. If charity overheads mean that amounts less than δ reach workers, there is a strong case for claiming that consumers should transfer an amount sufficient to ensure workers receive δ. As with direct transfers, this option depends on consumers’ own initiative, so ease of uptake is not a significant hurdle. However, the primary challenge for the charity approach is in matching the transfer of δ to affected groups.

5. CONCLUSION

We conclude that in most cases it is morally better for Alice to pursue the compensatory option than either of the other two options. The compensatory option promises to be superior to the dismissive option by ensuring that the workers who produced her new t-shirt have been compensated fairly; and superior to the instinctive option by contributing to the realization of the greater welfare benefits associated with garment jobs in Bangladesh. However, the compensatory option will not always be morally better.

As far as a defence of the dismissive option is concerned, if a case can be made for the claim that sweatshop workers are not paid unfairly, then the dismissive and compensatory options coincide. And if consumer demand for fairly produced goods is significant, then a portion of compensatory transfers is likely to be captured by firms. In such a scenario, the prospects for a boycott, and thus the instinctive option look much better. However, we hope to have shown above that neither of these scenarios is likely and for most consumers, in most cases, the compensatory option is superior to the dismissive option.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper was presented at two workshops on exploitation at Queen Mary University London, a Non-ideal Justice Workshop at the University of Amsterdam and the VU Amsterdam Practical Philosophy Colloquium. We thank those present for their comments. We also thank Brian Colgan, Martin van Hees, Alice Obrecht, Hillel Steiner, Roberto Veneziani, Gabriel Wollner and two anonymous referees for helpful suggestions.