In 1906, Dr. Nikolai Kostiamin, a hygienist and professor at the Imperial Military Medical Academy in St. Petersburg, published a series of short sex education essays informing low-ranking military personnel how to protect themselves from venereal diseases (VD). One essay recounted the story of a sergeant whom Kostiamin had met at a hospital in 1905. The sergeant had contracted syphilis after a drunken evening at a brothel and Kostiamin narrated the moment that the man learned of his diagnosis with dramatic flair: “I can't tell you without tears in my eyes and pain in my heart, dear brothers, how he prayed on his knees with a deluge of tears dripping on the floor” before he allegedly attempted suicide multiple times.Footnote 1 According to Kostiamin, the sergeant's diagnosis had transformed him from a respected military man into “a cripple” who would forever be deprived of “family happiness and the peaceful life of a worker” and would go on to produce children who were “freaks” (urody-deti).Footnote 2 It is impossible to know whether Kostiamin's turn of events is based on reality, or whether the story was entirely fictional. Nevertheless, Kostiamin's essay—just like other sex education materials prepared for military personnel—provides insight into the relationship between military masculinity and sexuality. In failing to control his impulses by drinking and engaging in paid sex, the sergeant had allegedly inverted his status from military defender of the empire to a burden to society and his family.

This article examines how sexual health became an important component of ideal military masculinity in the final decades of the Russian empire. Tsarist officialdom had long perceived the military as an important institution for preserving the social order and molding the attitudes, behavior, and bodies of the empire's male population to meet the needs of the autocracy.Footnote 3 The military's role in defining appropriate male behavior significantly expanded from the mid nineteenth century onwards following the disastrous defeat of the Crimean War. As part of Alexander II's Great Reforms, the military underwent a series of reforms throughout the 1860s and 1870s under the direction of War Minister Dmitrii Miliutin, with the aim of producing a modernized, professionalized and competent institution.Footnote 4 The previously draconian term of twenty-five years of military service was reduced to six, and recruits were obliged to undergo intensive military skills training and compulsory schooling.Footnote 5 Following the introduction of “universal” military conscription in 1874, military service became a compulsory individual obligation of (certain) male subjects, rather than a communal burden endured by serf/peasant communities.Footnote 6 In subsequent decades, military officials oversaw the moral “upbringing” (vospitanie) and physical preparation of current and future recruits with the goal of creating an efficient and loyal fighting force.Footnote 7

Through educational initiatives, military officials attempted to construct a “single, militarized, form of masculinity” that would unite male subjects across the multilingual and multi-ethnic space of the empire.Footnote 8 This model of ideal military masculinity was shaped by the needs of the state and was comprised of a series of behaviors and attributes that were lauded by military officials in a plethora of other international contexts, such as valor, physical and mental discipline, and unquestioning obedience to superiors.Footnote 9 In the Russian empire, ideal military masculinity was associated with discipline, modernity, and progress, and therefore was positioned in contrast to “backwards” rural society and the “unrestrained” habits of the urban poor. The construction of ideal military masculinity was an expansive project involving not just military planners and political leaders, but also medical professionals, who produced educational materials targeting the health and habits of conscripts. Military doctors drew a binary between specific hygienic behaviors that they deemed to be “masculine” and “modern” on the one hand, and “feminizing” and “backwards” practices on the other. This was especially true in sex education materials, in which men were warned that failing to exercise discipline, restraint, and good hygiene would have disastrous consequences for their social standing and impair their ability to productively contribute to their family units and society more generally. Through sex education materials, military physicians attempted to mold what they saw as unhygienic and ignorant peasant recruits into modern, healthy men who practiced self-control and good hygiene for the sake of their own health and public health more generally.

Russian military officials’ concern about the sexual health of military personnel was part of a broader international trend. Around the turn of the twentieth century, concern about the impact of high rates of VD among military personnel on national security was a topic of intense official and medical discussion in a plethora of international contexts, including imperial Austria, the British and French empires, and the United States.Footnote 10 Various national and imperial governments introduced measures with the stated aim of curbing the spread of VD in military populations throughout the nineteenth century, including the medical-police surveillance of women selling sex in ports and garrison towns, periodic sanitary inspections for military personnel, and numerous therapeutic and educational measures targeted at soldiers and sailors.Footnote 11 In the Russian empire as elsewhere, the military was the “ideal terrain for the experimentation and implementation of new medical technologies,” especially in the rapidly developing fields of venereology and syphilology.Footnote 12

While the Russian case aligns with broader international trends, VD control in the Russian imperial military was shaped by the empire's specific social and cultural context. In the Russian empire, public health practitioners largely regarded the primary route of VD transmission to be the “backwards” customs of rural life, rather than sexual contact. While physicians generally accepted that venereal diseases were sexually-transmitted infections in urban spaces, VD patients in the countryside—where the vast majority of the empire's population resided—were presumed to have contracted their infections through poor hygiene and the communal customs of rural life, such as sharing spoons, beds, and bowls with infected people.Footnote 13 At the first All-Russian Syphilis Congress held in St. Petersburg in 1897, delegates agreed that over three quarters of syphilis patients were such “victims of ignorance and low levels of culture.”Footnote 14 Soldiers and sailors in the peasant-dominated Russian military were presumed to be one of the chief transmitters of venereal infection in rural space. After contracting VD during their period of compulsory service, military men were believed to carry their disease back to their home regions and infect their families or others living in their localities. In 1907, an article published in Russia's primary venereological journal branded soldiers “hotbeds” of infection for this very reason.Footnote 15 Therefore, physicians regarded stemming the tide of VD in the military as crucially important for protecting public health more generally. Compulsory military service offered physicians the opportunity to transform “ignorant” peasants into modern and healthy men who abandoned the “backwards” customs of rural life in favor of adopting specific hygienic standards.

In examining military officials’ and physicians’ efforts to delineate the boundaries of men's appropriate sexual behavior, this article builds upon scholarship exploring the construction of masculinities in late imperial Russia. Rebecca Friedman's work on the nineteenth century has provided valuable insight into how the empire's young elites engaged with and resisted official visions of ideal masculinity within educational institutions.Footnote 16 How individual men negotiated the various contradictory prescriptions for masculinity that were in circulation throughout the nineteenth century has also been astutely analyzed using visual culture.Footnote 17 Historians have also examined how traditional models of masculinity that marked the patriarch of the peasant household as the ultimate authority and expression of manliness became increasingly challenged when rapid industrialization, urbanization, and the development of consumer culture shook the patriarchal gender order to the core at the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 18

The military is particularly fruitful for studying masculinities in the Russian empire because the connections between masculinity and the military were continually reinforced by the state and civil society. Russian officialdom regarded military valor as a universal attribute of all men and considered the military to be a key arena for molding male subjects into disciplined and obedient servants of the tsar.Footnote 19 The various hazards of military service, such as trauma and physical disability, challenged representations of the physically dominant and hypermasculine military hero that permeated tsarist military-patriotic discourses.Footnote 20 Looking to the military can also provide insight into the relationship between masculinity and sexuality. Irina Roldugina's work on homosexuality in the tsarist navy has demonstrated how appropriate sexual behavior was defined along the lines of class and military rank.Footnote 21 Building upon this work, this article examines how sexual health became a key arena for defining appropriate male behavior at the turn of the twentieth century. The sex education materials prepared by military physicians articulated a vision of ideal military masculinity that was focused on health, hygiene, and discipline, which served their broader goal of transforming the habits of peasant recruits for the benefit of public health more generally.

The Drive for Sex Education in the Military

In the Russian empire, the drive to provide the military with information and sexual hygiene happened against a backdrop of rising official concern regarding the sexual health of military personnel. In 1880, the War Ministry commissioned Veniamin Tarnovskii, a prominent syphilologist and professor at the Imperial Military Medical Academy, to compile an extensive report on the reasons behind the high rates of VD within the military.Footnote 22 At a meeting of the St. Petersburg City Duma in December 1883, deputy Litvinov claimed that a “significant number” of recruits drafted from the city in the previous year had been infected with syphilis.Footnote 23 At the turn of the century, the empire's principal venereological research journal, the Russian Journal of Skin and Venereal Diseases, frequently published articles penned by military doctors bemoaning the increasing rates of VD among troops stationed all across the empire, from Kiev (Kyiv) to Tashkent.Footnote 24

The tsarist authorities worried deeply about the impact of VD on the empire's future military elite. In 1893, the General Directorate of Military-Educational Institutions wrote to the Ministry of Internal Affairs to report a worrying trend observed among pupils of military schools, which were institutions within which the empire's future officer corps were educated.Footnote 25 Medical reports from military schools revealed that the average number of pupils diagnosed with diseases of the genitourinary organs had increased by over 136 per cent between 1866 and 1890.Footnote 26 The General Directorate also reported that over 66 per cent of cadets transferred to military schools in 1892 were infected with a venereal disease.Footnote 27 It is impossible to know whether these increasing rates were due to better record keeping or more frequent infection, but the tsarist bureaucracy went with the latter explanation. According to the General Directorate, the “unfavorable conditions of social life in big cities” were to blame for rising rates of infection, particularly the increased opportunities for cadets to engage in so-called “debauched” entertainment pursuits and pay for sex.

To reduce infection rates amongst military pupils, the Directorate wrote to the Ministry of Internal Affairs in April 1893 to call for the introduction of a series of urgent measures, including banning boys enrolled at military schools from brothels and the homes of independent prostitutes (odinochki). If a pupil was found to be infected with a venereal disease after paying for sex, the woman was to be fined and expelled from the city. Pupils were also prohibited from entering taverns, clubs, and public bathhouses, and only allowed to visit hotels and furnished rooms with the express permission of the head of their educational institution.Footnote 28 When attending public concerts, pupils were forbidden from meeting with actors and musicians after the performance. These measures rested on the perception that venereal diseases were spread throughout engagement in the broader “debauched” culture of urban life in the modern city, an idea that was widespread amongst state bureaucrats and medical professionals in the late imperial period.Footnote 29 In June 1893, the Department of Police issued a circular instructing all provincial police across the empire to implement the measures outlined by the General Directorate of Military-Educational Institutions.Footnote 30 Here, the Russian imperial police assumed a key role in preventing the perceived moral—and by extension physical—corruption of the empire's future military elite by restricting their access to specific urban leisure spaces.

Officialdom's drive to shield military school pupils from the health hazards associated with urban leisure reflects the growing significance placed upon the moral and physical development of the empire's future military servitors throughout the nineteenth century. In the first half of the nineteenth century, Tsar Nicholas I (1825–1855) expanded the institutional base of military schools and took great pains to develop and enforce new regulations targeting the minds, bodies, and morals of the empire's military elites-in-training.Footnote 31 The Russian government regarded military schools as training grounds for molding boys and young men to fit a set of gendered norms that would ensure their utility and loyalty to the autocracy. In this context, the male body was seen as a canvas upon which discipline, obedience, and ideal masculinity could be drawn. Pupils in the empire's Cadet Corps were required to endure an intense program of physical training and exposure to extreme temperatures, adhere to a myriad of strict rules governing all aspects of diet, hygiene, and physical appearance, and practice verbal and emotional self-control.Footnote 32 Discipline in military schools, and especially in the Cadet Corps, remained strict, despite the intense military reform coordinated by War Minister Dmitri Miliutin throughout the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s.Footnote 33 Therefore, rising rates of VD in military schools in the final decades of the nineteenth century greatly concerned the War Ministry as they provided evidence that the military education system was failing to mold the minds and bodies of the future military elite to fit with masculine ideals of self-restraint and discipline.

While state officials and physicians were somewhat concerned about the prevalence of VD amongst the empire's future military elite, they directed most of their attention to the sexual health of rank-and-file military personnel. This topic was high on the agenda at the Congress for the Discussion of Measures against Syphilis and Venereal Diseases, held in St. Petersburg in January 1897. The event was convened by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and attended by more than 450 professors, state officials, and zemstvo, military, and factory physicians.Footnote 34 Across eight days, delegates drafted dozens of recommendations for preventative healthcare, as well as for improving the existing treatment and supervision of syphilitics across the empire. The policies proposed by congress delegates exclusively targeted lower-class populations, such as peasants, factory workers, and low-ranking soldiers and sailors, reflecting the broad consensus within the Russian medical community that VD was primarily a disease of the poor and uneducated.Footnote 35 Recommendations for the military solely focused on the bodies and minds of the lower ranks, who would ideally be subject to more frequent examination and restrictions upon their leisure time and activities. To combat supposed ignorance about sexual health and personal hygiene, the “wide dissemination of information about syphilis and VD in the form of popular brochures” was deemed an urgent necessity, as well as “mandatory regular lectures by doctors” in language “accessible and understandable for the common people.”Footnote 36

In the years following the Congress, medical experts in military garrisons and ports in various parts of the empire developed sex education materials with increased frequency. In autumn 1897, the Military Governor of Kronshtadt, Nikolai Kaznakov, formed a commission of military doctors and immediately tasked them with discussing the new measures outlined at the Syphilis Congress and deciding which of them could be implemented in Kronshtadt.Footnote 37 Doctors in Kronshtadt enthusiastically answered the call for sex education, and eight military physicians quickly committed to giving “popular and comprehensible” lectures on VD to low-ranking military personnel.Footnote 38 Naval doctors in the port city of Libava (Liepāja, Latvia) gave lectures for sailors throughout the early 1900s with titles such as “Beware and be afraid of venereal diseases” and “The prevention of VD.”Footnote 39

Military physicians prepared brochures, pamphlets, and other printed materials to disseminate information about the transmission, symptoms, and prevention of VD to military personnel. The drive for new printed sex education materials coincided with the emergence of a “medical marketplace” in the Russian imperial context.Footnote 40 At the turn of the twentieth century, many reforming physicians regarded the popularization of medical knowledge as an important component of preventing the spread of infectious diseases and developed advice literature and self-help guides designed for mass consumption.Footnote 41 Personal health became a commodity to be bought and sold in commercial culture, as adverts for medical services, medicines, and advice literature exploited fears about disease and promised good health and self-improvement.Footnote 42 The increasing emphasis placed on literacy by the military authorities, combined with the continued expansion of basic schooling across the empire, meant that a growing number of military personnel could engage with popular health literature by the early 1900s.Footnote 43 The Chief Medical Inspector of the Navy capitalized on these rising literacy rates and oversaw the distribution of thousands of anti-VD pamphlets and books to low-ranking sailors.Footnote 44

The development of sex education materials for military personnel occurred against the backdrop of increased concern about the impact of poor health and perceived immorality upon the empire's future and security. Experts and officials alike worried deeply about the physical and moral quality of recruits and increasingly directed their energies towards disciplining the minds and bodies of military personnel. When medical professionals prepared sex education materials, they addressed men both as individuals and members of imperial society who had specific responsibilities to fulfil to ensure the health of their families and the existence of future generations.

Sex Education as an Individual Project

Sex education pamphlets, brochures, and lectures prepared for military personnel outlined visions of sexual morality that overlapped with the model of ideal military masculinity that was constructed by military officials. Through their participation in the project to construct ideal military masculinity, medical professionals added an air of scientific objectivity to discussions about appropriate male sexual behavior. Military doctors borrowed from class-based ideas about masculinity that contrasted the civilized and rational man who exercised full control over his body and mind with the uncontrolled primitive peasant or worker. Sex education materials emphasized the importance of practicing restraint and ensuring good hygiene to protect not only personal health, but also the very future of the empire.

In 1898, Kronshtadt doctor Nikolai Bogoliubov compiled a short instructional brochure for sailors on preventing VD.Footnote 45 Almost immediately after publication, hundreds of copies were distributed to naval units and hospitals in Kronshtadt and beyond.Footnote 46 The Chief Commander of Kronshtadt Port ordered that every literate sailor read the brochure and instructed quartermasters to read it aloud to all illiterate sailors. Bogoliubov's brochure provided graphic and scaremongering information on the symptoms and consequences of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid, as well as details about how to prevent these infections. The brochure also included various arguments for sexual restraint and even called for abstinence:

In order to keep yourself clean and to avoid VD, you should remain chaste. After finishing your time in the Tsar's service, you can build a respectable family life for yourself. Do not listen to your comrades who want to seduce you into drunkenness, bad deeds, and sexual intercourse. Remember the Russian saying: “take care of your clothes when they are new, and of your honor while you are young” [beregi odezhdu snovu, a chest΄ smolodu]. Always remember that a person cannot live without water or bread, but can live for several years without satisfying lust and passion. For example, monks do this, and we also do this when we meet moral people of the opposite sex.Footnote 47

Additional materials prepared for military personnel likewise insisted that resisting sexual impulses was a laudable goal, an idea that gained traction amongst a number of European venereologists and military physicians at the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 48 A collection of essays that was widely distributed to soldiers and sailors in the early 1900s included a number of treatises on abstinence.Footnote 49 In a short essay entitled “Male Chastity,” Dr V. Okorokov drew on insights from “modern medicine” to correct the apparently common (and in his opinion “absurd”) idea that abstinence was somehow harmful for men's health.Footnote 50 Okorokov claimed that abstaining from sex actually strengthened and revitalized the human organism and improved a man's mental faculties, drawing evidence from the “extraordinary physical strength” of the temperate and abstinent athletes of the antique world, the work of international specialists, and his own experiences with patients.Footnote 51 Another essay in the collection entitled “Human or Animal” provided a bullet-point list for how to “fight your debauched desires” and retain full control over one's mind and body. According to the list, there were many enemies of the abstinent man insidiously lurking in the rituals of everyday life, such as meat, sugar, alcohol, tobacco, tea, coffee, a comfortable bed, sleeping in a warm room, washing with warm water, idleness, and exciting conversations, books, music, and other forms of entertainment.Footnote 52 The author explicitly connected abstinence with manliness, branding anything that awakened sexual desire as “the habits of effeminacy” (iznezhennost΄) and placing those who repeatedly gave in to lust as “below animals” on the civilizational scale.Footnote 53 These messages stood in direct contrast to representations and performances of masculinity in other contexts, such as the village, the tavern, and the factory, wherein men's professed sexual virility and prowess were presented as important markers of manliness, and boasting about sexual conquest was deemed to be a common ritual of male bonding.Footnote 54

The promotion of abstinence in sex education essays existed uneasily alongside the fact that commercial sex was deeply embedded in the fabric of military life. Men who served in the lower ranks of the army and navy were forbidden from marrying while they were engaged in active service unless they obtained permission from their regiment commander and were willing to jump through a series of bureaucratic hoops.Footnote 55 In the Navy, high command acknowledged that the marriage ban likely contributed to sailors’ reliance on paid sex.Footnote 56 Even if military personnel had wives or long-term sexual partners back home, the territorial recruitment system stationed them far from their home regions.Footnote 57 Brothel keepers were well aware of the profit to be yielded from single men or those isolated from their wives and partners and opened their businesses close to military barracks.Footnote 58

Sex education initiatives within the military presented the sexual energy of the lower ranks as an important resource that ought to be channeled elsewhere. Physicians and pedagogues condemned masturbation as a waste of physical and mental resources that depleted the individual's (and by extension, the empire's) energy supply.Footnote 59 Similar messages were repeated in literature aimed at military men. For example, one 1899 manual produced for military pedagogues classified masturbation as a “disorder of the whole body” that resulted in “weakness” (slabosilie), scurvy, and even tuberculosis among the lower ranks.Footnote 60

In connecting manliness and strength to exercising sexual restraint, these texts engaged with discourses on masculinity that characterized willpower as the ultimate marker of manhood. At the turn of the twentieth century, self-help brochures and exercise manuals poured into the Russian mass market press instructing men how to attain the physical and mental “steeliness” (zakal) required to thrive in modern life.Footnote 61 Such discussions of self-improvement connected men's exertion of individual willpower with the more general commitment to transforming the “backwardness” that educated elites believed was permeating Russian culture and late imperial society.Footnote 62 This emphasis on individual qualities reflected a shift away from models of masculinity that rested upon subordination and deference to superiors (like the patriarch of the household) and moved towards the celebration of the entrepreneurial “self-made man” who thrived in the capitalist workplace.Footnote 63 In detailing the apparent health benefits of abstinence, sex education materials invited military men to participate in the empire's broader modernization project through redirecting their sexual impulses towards optimizing their physical and mental condition.

Alcohol was presented as the chief antagonist of self-control in sex education materials directed at military personnel. Drunkenness was a major problem in the tsarist military, and excessive alcohol consumption routinely thwarted the standards of discipline and subordination that were expected of military personnel.Footnote 64 Bogoliubov's brochure explained how drinking alcohol left military personnel in a vulnerable position, as drinking vodka and large quantities of wine destroyed men's willpower and impaired their judgement, leaving them vulnerable and “exposed” to the advances of “clandestine” (tainye) prostitutes, who disguised themselves as respectable women by wearing “insidious masks.”Footnote 65 “Clandestine prostitute” was the label that tsarist officialdom ascribed to women who illegally sold sex without registering their details with the police and attending biweekly gynecological examinations, in line with the rules of the state regulation system. These women were demonized in official discourse as an insidious threat to public health and the imperial police dedicated time and resources to exposing and prosecuting women deemed to be “clandestines.”Footnote 66 According to Bogoliubov, alcohol also had potent physical consequences beyond destroying men's ability to exercise mental strength. He warned sailors that having sex in a state of intoxication was likely to delay orgasm, and therefore, the longer period of sexual intercourse posed greater risk of infection.Footnote 67

Another brochure prepared for soldiers in the form of four “conversations” (besedy) with a doctor also detailed the destructive impact of alcohol on a man's ability to make sensible decisions regarding his sexual health. After drinking alcohol “a man ceases to take care of himself, forgets himself . . . and goes wherever he pleases or where his drunken comrade drags him.”Footnote 68 Intoxicated men allegedly engaged in sex “in a semi-conscious state” (so unable to check whether their sexual partner is displaying symptoms of VD) and after “having sexual intercourse frenetically, several times in a row,” they forgot essential post-coital prophylactic care, such as washing their genitals and urinating.Footnote 69 Another sexual health “conversation” published in the same brochure began with an emotional appeal to soldiers to refrain from drinking by remembering the faces of their families as they left the village for military service: “the grey-haired father who saw you off with tears, your old, dying mother, and your young healthy wife crying with her crying babies.”Footnote 70 Those who failed to remember the “affectionate looks of [their] wives and mothers” were seduced by the sight of bottles of vodka on display in shops in the city and, after drinking “to the sounds of the rattling harmonica and the rumble of roaring comrades,” “rush into the arms of a street walker” and contract a venereal disease.Footnote 71 The brochure recommended complete abstinence to preserve physical strength, as “depleting the body with women and vodka” allegedly caused it to “shrivel, weaken, and wither like a tree with rotten roots and leaves that have been gnawed away by insects.”Footnote 72 Therefore, self-control was essential for preserving the physical and mental strength required of military men.

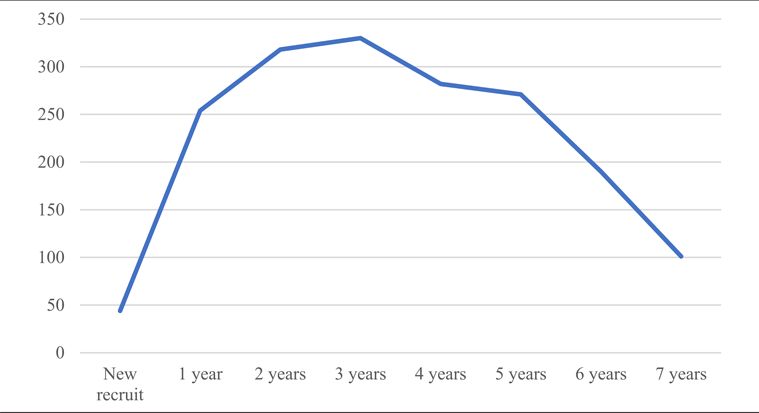

As well as drawing connections between alcohol, VD, and physical/mental weakness, sex education brochures also highlighted the apparent corrosive impact of military service upon men's health and morality. One brochure lamented that “healthy and rosy” young men entered military service and later became corrupted by the “dirty pleasures” of urban life.Footnote 73 Bogoliubov's brochure for sailors claimed that recruits entered service “innocent, chaste and righteous” but destroyed their health by learning to drink vodka and engaging in casual sex while in the navy.Footnote 74 Military doctors shared these concerns. In a May 1899 report, doctors at Kronshtadt's Nikolaev Naval Hospital claimed that lower infection rates for new recruits and men in their first year of service indicated that they had not yet become “acquainted with the charms of the city” and “spoiled” scenarios which they claimed became more likely throughout the next five years of their service.Footnote 75 The Kronshtadt doctors also reported that men in their final year of service were less likely to become infected because they were thinking about returning home and therefore, refrained from temptation. Similar trends were observed by naval doctors at Nikolaev Naval Hospital in Kronshtadt and the port of Nikolaev (Mykolaiv, Ukraine) in the early 1890s. Table 1 and 2 indicate that sailors in Kronshtadt and Nikolaev tended to become infected with syphilis, gonorrhea, or chancroid during the first half of their period of service, and were less likely to contract an infection shortly before returning home.

Table 1. Number of VD patients admitted to Nikolaev Naval Hospital in Kronshtadt by length of service, 1898.

Source: RGAVMF, f. 930, op. 5, d. 105, l. 5.

Table 2. Number of VD patients registered at Nikolaev port by length of service, 1889–1893.

Source: RGAVMF, f. 1094, op. 1, d. 269, l. 453.

Assessing the impact of military service on men's sexual health is challenging because the available data is fragmented and there is no comparable data capturing VD across the empire's male civilian population.Footnote 76 Tables 1 and 2 indicate a general trend in two specific ports, but the statistics presented must be treated with caution given the difficulties associated with diagnosing VD (especially syphilis in the latent stages of infection) in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 77 While finding statistical confirmation that the military had an adverse impact on men's sexual health might not be possible, it is likely that military men did experience significant rates of infection because many paid for sex, an activity that carried a high risk of contracting VD. It was very common for registered prostitutes to contract VD over the course of their working lives. In fact, 40 per cent of women registered on the police lists in the European portion of the Russian empire had a venereal disease in 1909, and women who sold sex without registering with the police likely experienced similar or even higher rates of infection.Footnote 78

Military officials were uncomfortable with prostitution, but often regarded state-licensed brothels as a healthier alternative to paying for sex with unregistered “clandestine” prostitutes. Brothel workers were (in theory) subject to biweekly gynecological examinations, which convinced military officials that having sex within the brothel was safer than elsewhere. For example, in November 1903, the Kronshtadt Military Governor wrote to Naval Ministry to protest the planned closure of several brothels that were located close to the town's naval barracks following complaints by local homeowners. “While I recognize that brothels are evil in moral terms, this evil must be tolerated in towns because it saves us from a greater evil: clandestine prostitution,” he warned, before outlining the potential detrimental impact of the brothel closures on the health of the lower ranks.Footnote 79 Sex education materials also acknowledged the fact that military men were likely to pay for sex and attempted to steer men towards state-licensed brothels. Bogoliubov's brochure for the lower ranks of the Navy instructed men who could not resist their sexual impulses to go to the brothel, or as he called it “the necessary evil of our society.”Footnote 80 For Bogoliubov, brothels were safer because women were subject to examinations and men were able wash their genitals after sex due to brothel keepers’ legal obligation to provide warm water and soap for customers. Another brochure told military personnel who “could not resist women's caresses and seductive talk” that the brothel was safer than the “dirty kennel of a cheap clandestine.”Footnote 81 Whether brothels were safer is questionable, because financial incentives often overrode brothel keepers’ legal obligations to ensure disease-free sexual intercourse for customers. Many brothel madams failed to pay for their workers’ medical examinations and prevent infected women from working, and, thanks to the well-established practice of bribing police patrolmen, faced no legal consequences.Footnote 82

While some commentators begrudgingly accepted that paying for sex was a common leisure activity for military men, others directed the lower ranks towards different ways to spend their free time. In response to rising rates of VD in the late 1890s, a commission of naval doctors in Kronshtadt recommended organizing activities for the lower ranks that were “very popular among common people,” such as crafts and folk dancing events in public gardens.Footnote 83 In Libava, the Society of Naval Physicians emphasized the “need to distract sailors from their desire to drink and engage in debauchery” by organizing more “appropriate” activities, such as gymnastics and drama clubs, as well as reading groups on history, geography, and hygiene.Footnote 84 Other naval physicians in Libava promoted “outdoor games,” reflecting the cultural elite's prescription of exercise and fresh air as key remedies for the physical and mental deterioration characteristic of life in overcrowded cities.Footnote 85 In September 1909, the Medical Inspector of Libava's military port and the chief doctor of Libava's naval hospital declared a “struggle against idleness” and called for “intensified mental and physical labor” for sailors.Footnote 86 They recommended that sailors be encouraged to engage in “rational entertainment,” namely improving their literacy, crafts, swimming and other sports. These recommendations were repeated in certain sex education brochures, wherein military personnel were instructed to practice gymnastics and “read useful books recommended to you by your superiors.”Footnote 87

Aimed exclusively at the lower ranks of the military, calls for “rational entertainment” reflected a European trend of attempts to “civilize” working-class men and women at the hands of their social superiors. For the educated public, this often involved guiding lower-class people away from their supposed uncivilized and “immoral” leisure activities towards more middle-class interests, such as classical art and literature.Footnote 88 In the context of the Russian empire, these recommendations were tinged with the hues of paternalism. The ideology of the tsarist autocracy outlined the ideal relationship between the tsar and his people as that of father and son: the tsar was obliged to protect his subjects and they were to obey him unquestioningly. Paternalism also permeated interactions between doctors and their lower-class patients, who they largely presumed to be ignorant and in need of direction from their social superiors. Educated elites approached the reduction of VD as a “‘civilizing’ and ‘disciplining’ mission,” to not only improve lower-class populations’ living conditions and access to healthcare, but also their physical and moral state.Footnote 89 Naval doctors who addressed rising rates of VD in the military advocated for the expansion of treatment facilities alongside the stricter supervision of recruits. For example, in the late 1890s naval doctors in Kronshtadt claimed that sailors could not be trusted to travel to the hospital for treatment and should be sent with “reliable escorts” to prevent them from “roaming around the town.”Footnote 90 Naval doctors in various ports called for the stricter supervision of lower ranks at night, to ensure that they remained in their barracks and were not left unsupervised.Footnote 91

For certain physicians, military service provided an opportunity to transform peasant recruits into healthy, modern men by instilling new hygienic norms and practices. In this respect, military physicians participated in the broader project to “nationalize” masculinity following the introduction of universal conscription, wherein military institutions endeavored to transfer the authority that defined the masculine ideal from local communities onto state representatives.Footnote 92 For military physicians, ideal military masculinity included specific standards of health and hygiene, and many doctors attempted to eradicate unhygienic practices that they believed to be prevalent within rural communities. While medical professionals generally regarded VD as a sexually transmitted disease in urban contexts, many believed that syphilis was primarily spread in the absence of sexual contact in the countryside through the “backwards” rituals of rural life, namely communal sleeping, infrequent washing of clothes and linen, and the sharing of eating utensils.Footnote 93 Delegates at the 1897 Syphilis Congress agreed that over three quarters of syphilis patients were such “victims of ignorance and low levels of culture”: peasants who caught the disease through poor hygiene.Footnote 94 As over 80 per cent of the empire's population were classified by the tsarist authorities as peasants, recruits from the countryside dominated the military's lower ranks.Footnote 95

Officials and physicians alike regarded instilling hygienic habits in the peasant-dominated military as an important endeavor that would have positive consequences for public health within the countryside in general. After learning how to keep themselves clean and prevent VD, military men could then share this knowledge within the village and enforce new hygienic norms. From the perspective of military physicians, equipping soldiers and sailors with hygienic knowledge would also prevent them from carrying their disease back to their home regions, which medical professionals believed to be one of the principal causes for syphilis outbreaks among rural populations.Footnote 96 In sex education brochures and public lectures, military personnel were constantly reminded of washing their bodies regularly with warm water and checking their genitals for signs of VD daily.Footnote 97 One anti-VD brochure called Quick, to the Doctor! that was distributed to low-ranking military personnel outlined the importance of cleanliness and explained that men had a responsibility to set the hygienic standards of the entire household. The author, county doctor (uezdnyi vrach) K. Dovodchikov, published several popular brochures intended for mass circulation in the late 1890s. In Quick, to the Doctor! he contrasted the baby (a derogatory term for peasant women) with the muzhiki (peasant men) to emphasize his point:

No, dear man, do not skimp on soap, buy it freely. The cost will always justify itself. Baby, after all, are much more stupid. You are the head of the household and family. Make it a rule that every morning everyone should wash their faces with soap . . . Some baby are reasonable, but muzhiki are more competent. That's why I am addressing this to muzhiki. Footnote 98

According to the Dovodchikov, indifference to cleanliness did not only indicate limited intelligence, but was also akin to feminization. Masculinity was defined by adherence to specific standards of health and hygiene, and by enforcing these standards on the subordinate members of the household. By delivering these messages to military personnel, physicians encouraged military men to participate in the broader modernization of the empire by eradicating the unhygienic habits that caused the spread of infectious diseases like syphilis and gonorrhea.

Sex Education as a Community Project

Sex education materials for military personnel articulated a clear vision of the appropriate place of men within society and the family. A brochure prepared by Dr. M. Tsatskin, a junior doctor serving in the Perevolochenskii regiment, warned men that “health is all your capital and getting sick spends it,” because with illness came the inability to work and earn a living.Footnote 99 Dr. A. Nedler's 1897 anti-syphilis pamphlet for the lower ranks of the military warned that leaving the disease untreated would have disastrous consequences for a man's social standing, as by extension, his masculinity: “not only is he no longer a worker, but he also distracts others from work as he must be looked after.”Footnote 100 According to Nedler, ignoring syphilis symptoms forced men into a passive role, inverting their status from providers to financial burdens to their families.

In the Russian empire as elsewhere, “forms of masculinity organized around wage-earning capacity” emerged in tandem with the acceleration of industrialization and the profound social consequences that accompanied it.Footnote 101 In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, millions of rural subjects of the empire left the countryside in search of wage labor, settling in provincial towns and cities on a temporary or more permanent basis.Footnote 102 Mass migration for wage labor began to undermine the economic underpinnings of generational patriarchy, as it provided young men (and to a lesser extent, young women) with greater economic independence and even the potential to permanently leave the patriarchal stronghold of the multi-generational peasant household. Therefore, warnings about the impact of VD on a man's ability to generate income reflect the increased importance placed upon wage labor in constructions of masculinity in the early twentieth century.

Sex education materials also reminded military men of their responsibility to produce healthy offspring and ensure the future of the empire. One sex education pamphlet warned military personnel that contracting syphilis would make them a “cripple (kaleka) for life” who would bear sick and suffering children.Footnote 103 Similarly, in another popular brochure, military personnel were repeatedly warned that contracting venereal infections, especially syphilis, would turn them into “cripples” whose children would be “freaks” who “suffer all their miserable lives” from a plethora of painful physical and mental illnesses.Footnote 104 Abstaining from both alcohol and sex during military service were presented as the only sure methods to “keep healthy and strong” and “serve the Tsar and the Fatherland reverently and honestly.”Footnote 105 In defining the duties of military service in hygienic terms, sex education materials facilitated the emergence of the “hygienic citizen,” whose good sexual health was of paramount importance to the present and future of the empire.Footnote 106 This “hygienic and reproductive imperative” placed limitations on the sexual lives of military personnel, who were encouraged to practice abstinence to ensure the future existence of the monogamous reproductive family.Footnote 107

In focusing on the impact of VD on future generations, sex education materials echoed transnational discussions regarding eugenics and degeneration theory. Influenced by ideas of social Darwinism, various medical professionals both within and beyond the Russian empire argued that the unprecedented social upheaval of mass urbanization and industrialization that occurred during the nineteenth century had caused humanity to regress. Like their counterparts abroad, Russian public health experts regarded increased VD as another manifestation of the dark side of modern life and indicative of the broader moral and physical degeneration perceived to be infecting humanity.Footnote 108 The vocabulary of degeneration was not merely confined to scientific discourse, and instead metaphors of sickness and infection permeated literature, art, and popular journalism in the Russian empire.Footnote 109 At the turn of the twentieth century, concern about the physical and moral impacts of industrialization and urbanization and the rapid expansion of the human and medical sciences meant that eugenic ideas started to filter into medical, criminological, and anthropological discourse.Footnote 110 The proliferation of these ideas encouraged public health experts to interpret the nation—or in the Russian case, the empire—as an object of scientific study and a “biological entity whose natality, longevity, morbidity, and mortality needed to be supervised.”Footnote 111 Within this context, keeping the male military body (and its offspring) healthy was deemed especially important, as poor health and hereditary illness had the potential to undermine future military strength and national efficiency. Therefore, the importance of men's sexual health was often cast in national or even civilizational terms.

The Impact of Sex Education Initiatives

Assessing how successful medical professionals were in inculcating hygienic norms and standards of behavior is incredibly difficult, namely because sources detailing the reactions of military personnel to sex education initiatives are not available. However, we can conclusively say that sex education brochures and lectures had little impact on rates of VD in the Russian imperial military, which continued to climb throughout the early 1900s. This is likely because sex education could not solve the structural problems causing high incidence of VD, such as the tsarist state's chronic underinvestment in treatment facilities and a lack of dedicated medical personnel specializing in venereology. The spread of knowledge about the treatment and prevention of VD—through sex education materials or otherwise—did have an impact in the military and influenced the kinds of treatments that military personnel sought when they became infected. Examining the (perhaps unintended) repercussions of experts’ attempts to construct military masculinity reveals the impact that the “inculcation of professional knowledge through broad military circles” had upon men's behavior.Footnote 112

The tsarist government had a poor track record when it came to funding civilian and military healthcare. The central government deemed zemstvo and municipal institutions responsible for civilian public health and medical assistance, but these organizations were frequently overburdened with an immense list of other administrative responsibilities and too poorly funded to organize adequate healthcare provision for the civilian population.Footnote 113 In contrast, healthcare for military personnel was centralized, and both the armed and naval forces had their own chief medical inspectors who operated under the supervision of the Ministers of the War and Navy, respectively.Footnote 114 However, administrative supervision did not guarantee adequate healthcare facilities for military personnel. A damning report on VD treatment facilities at military hospitals from 1880 concluded that the conditions in the Kiev, Vil΄na (Vilnius, Lithuania), and Moscow military hospitals were unhygienic and that patients were frequently discharged before the end of their treatment in order to save space.Footnote 115 The report also claimed that the equipment in most military hospitals “did not meet the most modest requirements of modern medicine,” which resulted in prolonged treatment times, overcrowded conditions, and frequent relapse following the patient's discharge from the hospital.Footnote 116 Military doctors were also poorly trained in syphilology and venereology, which led to frequent misdiagnoses and ineffective treatment.

Conditions in military hospitals likely did not drastically improve in the decades that followed the 1880 report, especially given the tsarist government's track record in underfunding healthcare. Articles in medical journals lamented the lack of trained personnel and adequate medical facilities for the treatment of military personnel.Footnote 117 Higher infection rates in specific areas of the empire suggest that medical facilities were even worse for soldiers and sailors stationed in regions that lacked large military hospitals. For example, in 1910, five per cent of military personnel were infected with VD across the entire Imperial Army and Navy, but the figures were lower in St. Petersburg and Warsaw (three per cent), as well as Kiev (four per cent). In contrast, fifteen per cent of soldiers stationed in the Omsk region of western Siberia had VD, as well as twelve per cent of those in the Don Cossack region and ten per cent in Irkutsk.Footnote 118

Military personnel were guaranteed free treatment for VD, but there were significant obstacles to delivering this in practice because of chronic underfunding and the inadequate supply of medication. The impact of this disastrous combination is evident by focusing on one specific anti-syphilis treatment. In 1909 the first effective cure for syphilis was developed at the laboratory of German immunologist Paul Ehrlich.Footnote 119 This would soon become an intravenous injection known as Salvarsan, 606, or the “magic bullet.” Salvarsan was a popular treatment with syphilis patients in the Russian empire because it was both effective and had fewer painful side effects than mercury therapies. In March 1911, the Navy's Chief Medical Inspector claimed that the treatment was now “known to every literate person” and that low-ranking sailors were demanding it in naval hospitals.Footnote 120 If the hospital was unable to provide the treatment because of issues with funding, the lower ranks were allegedly procuring it from “outsiders.” Even when naval physicians emphasized that Salvarsan was not a “complete and perfect cure” for syphilis, sailors kept demanding it.Footnote 121 To solve the problem, Kronshtadt naval hospital offered sailors the option to purchase an ampule from the hospital's pharmacy for 2 rubles and 86 kopecks, a price significantly cheaper than buying Salvarsan from a private pharmacist.Footnote 122 This angered the Navy's Chief Medical Inspector, who insisted that sailors paying for any treatment was “incompatible with the conditions of naval service” as military personnel were guaranteed free treatment for VD.Footnote 123

Complicating matters further was the fact that the Naval Ministry did not provide hospitals with enough funding for Salvarsan to meet patient demand. The Chief Medical Inspector of the Navy warned that the unavailability of Salvarsan in naval hospitals had the potential to bring about serious reputational damage, as it suggested that the medical care provided for the lower ranks was “unsatisfactory.”Footnote 124 In 1912, chief physicians at naval hospitals in the Baltic ports of St. Petersburg, Libava, Revel΄ (Tallinn, Estonia), Kronshtadt, and Vladivostok complained that the Navy's Medical Department did not provide adequate funding to purchase enough Salvarsan to keep up with demand.Footnote 125 In some regions of the empire, the treatment was completely unavailable. Sailors in the Caspian Flotilla (headquarters in Baku, now Azerbaijan) had to travel over 1500 km to Sevastopol΄ to receive the Salvarsan injection.Footnote 126

The case of Salvarsan reveals the complications and contradictions of the project to construct ideal military masculinity. Military personnel seeking treatment when they became infected with VD and demanding the most effective cures were exhibiting the kinds of values characteristic of the modern, hygienic man that was described in sex education materials. Rather than ignoring their symptoms, they understood the importance of personal health, and by extension, the health of the empire. The empire's inadequate health infrastructure and tsarist government's consistent underinvestment in treatment, however, made adherence to the hygienic standards of ideal military masculinity incredibly difficult, or even impossible. Things would become even worse as the Russian empire plunged into war in 1914, which shook the already inadequate foundations of the tsarist healthcare system to the core. Rates of VD among military personnel soared as disease ravaged the civilian population and doctors were drafted into the war effort.Footnote 127 Faced with a catastrophic situation, the military authorities attempted to stem the streams of VD patients in military hospitals. On January 16, 1915, the Military Medical Directorate Supreme Chief issued Order No. 28, a directive that forbade the admission of soldiers and sailors infected with VD to hospitals unless their disease was in its most severe form.Footnote 128 Because of this order, hundreds of thousands of military men with highly infectious venereal diseases were evicted from treatment facilities or simply left untreated. Order no. 28 was not cancelled until July 1917, when solving the problem of VD in the military and instilling hygienic norms within military and civilian populations became the new government's problem.Footnote 129

In the late Russian empire, state officials and medical professionals worked together to outline a vision of ideal military masculinity that served the broader goals of improving military and public health. Rising rates of VD in the military in the final years of the nineteenth century forced the Russian imperial state to increasingly turn their attention to the sexual health and hygienic habits of military personnel and enlist the help of military physicians to reduce rates of infection. Reform-minded physicians enthusiastically embraced the opportunity to communicate directly with low-ranking soldiers and sailors and approached the task as a civilizing mission. The sex education materials that they prepared encouraged recruits to abandon the habits and practices of rural life and embrace “modern” hygienic manhood. Physicians saw military personnel as an important link to the empire's vast lower-class population and regarded the inculcation of new norms of health and hygiene within military populations as a key method for improving public health more generally, especially in the countryside. If men could change their hygienic and sexual habits during military service, then perhaps they would continue to live healthy lives following their discharge from duty and go on to influence the behavior of their families and wider communities.

Studying sex education materials prepared for military personnel reveals the centrality of sexuality to conceptions of masculinity at the turn of the twentieth century. In sex education brochures and lectures, physicians presented men's ability to abstain from sexual intercourse and redirect one's sexual energies as the ultimate marker of manhood and a broader indication of their mental and physical strength. Physicians and pedagogues frequently referenced men's role as providers—both of income for families and offspring for the future of the empire—to stress the urgency of keeping oneself sexually healthy. Military doctors cast concern for personal hygiene and health as an endeavor that gave men the potential to climb the hierarchy of hegemonic masculinity. By frequently washing, engaging in post-coital prophylactic care, and visiting the doctor for treatment, military men could transcend the supposed ignorance and backwardness of their counterparts who they had left behind in the village. However, the conditions of military service and the Russian empire's inadequate health infrastructure placed limitations on how far men could live up to the ideals of the modern, hygienic man outlined in sex education.