Courts often have opportunities to affect the integrity of elections, even in authoritarian or semidemocratic settings. At times, these opportunities can be dramatic, as when the Ukrainian Supreme Court ordered a rerun of a vote in the 2004 presidential election following mass protests. Courts can influence election outcomes in more mundane ways as well. In civil cases, courts can register or deregister candidates for an election and adjudicate other claims of procedural unfairness (Bækken Reference Bækken2015; Popova Reference Popova2012); in criminal cases, they may apply fines or prison time to individuals caught engaging in illegal forms of electoral manipulation. For example, in June 2019 a Russian district court fined a member of a precinct election commission 40,000 rubles for the falsification of two ballots in favor of the ruling party, under pressure from the opposition.Footnote 1 Taken together, decisions by courts up and down the judicial hierarchy may be able to enhance electoral integrity or diminish it, depending on whether they tend to rule for or against the interests of the ruling party.

Within the large literature on the role of democratic institutions in nondemocratic contexts, the judiciary has increasingly become an object of study. A fruitful recent strand of research has challenged the conventional wisdom that independent courts are beneficial for democracy and democratization (Helmke and Rosenbluth Reference Helmke and Rosenbluth2009) by identifying a variety of benefits that ruling parties in authoritarian and hybrid regimes can reap by granting some measure of genuine independence to their courts (Ginsburg and Moustafa Reference Ginsburg and Moustafa2008). These benefits include monitoring of citizens and officials, securing investment and property rights, and regime legitimation, among others. As a result, many nondemocratic systems have adopted formal institutions of de jure judicial independence, yet we have conflicting theories of how such institutions affect another central institutional feature of modern nondemocracies—manipulated multiparty elections. One view holds that more independent courts will reduce manipulation during competitive elections due to protest risk (Chernykh and Svolik Reference Chernykh and Svolik2015); another view finds that high competitiveness drives ruling parties to intervene to secure favorable outcomes in election cases (Popova Reference Popova2012), implying favorable conditions for manipulation.

This paper offers a new theory of judicial independence and election manipulation—in the context of ordinary courts rather than high-profile decisions to uphold or annul elections—offering novel predictions that are supported by cross-national data. It argues that nondemocratic governments establish de jure independent courts in order to capture a variety of benefits, many of which have little to do with electoral competition directly. These reforms increase the likelihood of legal mobilization among opposition groups and parties, bringing more cases to the courts that allege pro-government electoral malfeasance (Aydın-Çakır Reference Aydın-Çakır2014; Dotan and Hofnung Reference Dotan and Hofnung2005; McCann Reference McCann1994). As a result, even if the rate at which courts rule against the government remains constant, the absolute number of unfavorable rulings for the government is liable to increase. Consequently, illegal election manipulation is likely to decrease following de jure reforms due to two complementary mechanisms. In some cases, the risk that adverse rulings may undermine the legitimacy of the ruling party (Berman, Shapiro, and Felter Reference Berman, Shapiro and Felter2011; von Soest and Grauvogel Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017) may cause it to voluntarily engage in less manipulation. At the same time, increased risk of legal exposure for low-level election-manipulating agents makes it more difficult for the ruling party to rely on them to manufacture votes (Rundlett and Svolik Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016).

Crucially, the size of this effect is responsive to strategic decisions by the ruling party to apply informal pressure on the courts. When elections are uncompetitive and the ruling party believes itself secure, it can tolerate adverse rulings from the courts more readily. As competition increases, the ruling party faces stronger incentives to use the tools at its disposal to pressure judges to rule favorably (Ellett Reference Ellett2013; Popova Reference Popova2012; VonDoepp Reference VonDoepp2009). As a result, de jure reforms are most likely to lead to reductions in election fraud in highly authoritarian settings with little political competition but have less influence in more open and competitive nondemocracies.

Though this study relies on observational data (Harvey Reference Harvey2022), the results are robust to different model specifications and preprocessing techniques that can mitigate concerns about selection effects and endogeneity. By weighting observations to better approximate unobserved counterfactuals, these techniques reduce the risk of misidentifying the nature of the relationship between the variables. The analysis draws on data from 1,009 election-year observations in 130 countries from 1945 to 2014 including a range of authoritarian regimes, hybrid regimes, and electoral (not liberal) democracies.

This article makes three main contributions. First, it offers a new theory of the relationship between judicial independence and election manipulation, a substantively important topic given the prevalence of electoral authoritarian regimes and de jure independent courts in nondemocracies (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Magaloni and Kricheli Reference Magaloni and Kricheli2010; Staton, Reenock, and Holsinger Reference Staton, Reenock and Holsinger2022). This theory makes different predictions than protest-oriented views of courts and election fraud (Chernykh and Svolik Reference Chernykh and Svolik2015), showing that formally independent courts can reduce fraud when political competition (and thus protest risk) is low. Likewise, this theory suggests a modification to a standard principal-agent model of fraud (Rundlett and Svolik Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016), which holds that election-manipulating agents only face risks if their patron is defeated and thus predicts that fraud diminishes as competitiveness increases. Instead, I argue that agents may fear legal risks even if their party wins. Notably, judicial reforms do not reduce the level of fraud when specialized election courts exist that can shield agents from legal consequences and regimes from negative publicity. Last, this project goes beyond the predictions of Popova’s (Reference Popova2012) strategic pressure theory by showing how institutional reforms, in combination with opposition incentives to litigate, can lead to improved election quality in low-competition environments.

Second, prior work on this subject, although path-breaking, has either been rooted in formal theory, with little empirical testing, or based on detailed case studies. To my knowledge, this is the first cross-national empirical study of the effect of de jure judicial independence on election fraud and related abuses outside liberal democracies.

Third, this project offers a framework for thinking about the empirically tangled relationship between courts’ de jure and behavioral independence (Herron and Randazzo Reference Herron and Randazzo2003; Melton and Ginsburg Reference Melton and Ginsburg2014). The scope conditions of this theory, focusing on nongovernment actors’ incentives to go to court and ruling parties’ shifting incentives to apply judicial pressure, offer predictions about the settings under which de jure reforms can translate into improved behavioral independence in nondemocracies in other case domains, suggesting a way forward in studies of judicial independence.

Judicial Independence and Electoral Manipulation

Judicial independence remains a somewhat contested concept, but at the core, it requires that courts be capable of acting as impartial decision makers, resolving disputes without undue pressure from other political actors (Burbank and Friedman Reference Burbank and Friedman2002; Linzer and Staton Reference Linzer and Staton2015). Researchers regularly draw a distinction between de jure judicial independence—“formal rules designed to insulate judges from undue pressure” (Ríos-Figueroa and Staton Reference Ríos-Figueroa and Staton2014, 106)—and behavioral, de facto independence.

Judicial independence is generally taken to be positive for democratic governance—though with the caveat that it may confound majority rule (Helmke and Rosenbluth Reference Helmke and Rosenbluth2009). An independent judiciary can protect civil and political rights (Crabtree and Nelson Reference Crabtree and Nelson2017; Larkins Reference Larkins1996; Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996), provide a focal point for citizen coordination (Weingast Reference Weingast1997), and help maintain the rule of law (Dahl Reference Dahl1957; Landes and Posner Reference Landes and Posner1975). Furthermore, established independent judiciaries can help prevent authoritarian backsliding in a crisis (Gibler and Randazzo Reference Gibler and Randazzo2011; Graham, Miller, and Strom Reference Graham, Miller and Strom2017).

However, recently it has become clear that some measure of judicial independence can benefit ruling parties in nondemocracies. Independent courts can help gather information on citizen grievances, monitor social discontent (Ríos-Figueroa and Aguilar Reference Ríos-Figueroa and Aguilar2018) and excessive abuses by lower-level agents of the regime (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg, Ginsburg and Moustafa2008), legitimate the regime through appeals to the rule of law (Moustafa Reference Moustafa, Ginsburg and Moustafa2008; Whiting Reference Whiting2017), protect investments (Moustafa Reference Moustafa, Ginsburg and Moustafa2008), reduce uncertainty and the risk of internal conflict (Sievert Reference Sievert2018), make postelection protest by opposition groups less likely (Eisenstadt Reference Eisenstadt2003), and police possible threats to the ruling party from other power centers in society (Ma Reference Ma2017). As a result, many authoritarian regimes have adopted one or more of the formal institutions that preserve judicial autonomy. Such de jure reforms can include lengthening judicial tenure, insulating judicial salaries from political interference, amending selection procedures to limit political pressures (e.g., through judicial councils), and restricting the conditions under which judges may be disciplined or dismissed (see Staton, Reenock, and Holsinger [Reference Staton, Reenock and Holsinger2022, 67–72] for a more detailed overview of these institutions). Crucially, regimes may adopt these reforms in order to capture the benefits listed above, which have little to do with liberalization or a desire to win elections.Footnote 2

Nevertheless, it is also clear that an independent judiciary can be a double-edged sword, creating “a uniquely independent institution with public access in the midst of an authoritarian state” (Ginsburg and Moustafa Reference Ginsburg and Moustafa2008, 13), allowing for opposition actors to challenge—and sometimes defeat—the state. After all, authoritarian governments only reap the benefits of enhanced investment, greater legitimacy, and more control over agents if independent courts do in fact constrain arbitrary uses of state power. It is also well established that governments in nondemocracies routinely use informal pressure techniques—such as threats, physical attacks, bribes, and social ties (Ledeneva Reference Ledeneva2008; Llanos et al. Reference Llanos, Weber, Heyl and Stroh2016; Solomon Reference Solomon2010)—to influence judges’ rulings in particular cases of high interest to the regime while allowing courts to rule more independently on other topics (Moustafa Reference Moustafa2003; Popova Reference Popova2012; Taylor Reference Taylor2014; Wang Reference Wang2020). In other words, it is possible for courts in nondemocracies to be allowed to rule independently in nonsensitive domains while facing pressure to fall in line in more sensitive cases. Moreover, it is possible for the same policy domain to be nonsensitive under some circumstances but to become sensitive—and subject to pressure—as circumstances change.

The conduct of an election is one such policy domain. There is no shortage of tools with which ruling parties may bias the outcomes of elections in nondemocracies (Norris Reference Norris2015; Schedler Reference Schedler2002). These include techniques that are almost always against the law such as ballot-stuffing or falsification (van Ham and Lindberg Reference van Ham and Lindberg2015), voter pressure (Frye, Reuter, and Szakonyi Reference Frye, Reuter and Szakonyi2014), or intimidation (Asunka et al. Reference Asunka, Brierley, Golden, Kramon and Ofosu2017; Mares and Zhu Reference Mares and Zhu2015). Severe election manipulation is not limited to competitive races but can occur in highly authoritarian states as a signal of dominance (Simpser Reference Simpser2013) or through a bandwagon effect by subordinates eager to be on the winning side (Rundlett and Svolik Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016).

Illegal forms of electoral malfeasance are regularly addressed by courts in response to complaints by citizens, candidates, or parties (Birch and Van Ham Reference Birch and Van Ham2017; Eisenstadt Reference Eisenstadt2003). When cases of illegal electoral misdeeds come before courts in nondemocracies—often through the work of election observers and opposition activists—there are multiple avenues through which judiciaries may exert influence (Orozco-Henríquez, Ayoub, and Ellis Reference Orozco-Henríquez, Ayoub and Ellis2010, 86, 138–9). As redress, courts can order recounts or nullify contested election results (Chernykh Reference Chernykh2014), but they may also apply criminal or administrative penalties for those who violate electoral law.Footnote 3

How might courts influence election integrity in nondemocracies? Two mechanisms are contemplated in prior work. First, Chernykh and Svolik (Reference Chernykh and Svolik2015) argue that more independent courts reveal more information about fraud, which raises the risk of postelection protest; fearing this, ruling parties perpetrate less fraud in competitive conditions. However, in some cases, information about election manipulation may actually reduce the risk of protest by signaling regime strength (Harvey and Mukherjee Reference Harvey and Mukherjee2020; Simpser Reference Simpser2013), calling this proposed mechanism into question. A second school of thought holds that increased competitiveness drives ruling parties to put increased pressure on the courts, allowing them to prevail in election-related cases (Popova Reference Popova2012). Thus, there are competing predictions for the role that competitiveness plays in allowing courts to restrain election manipulation.

Finally, alternative explanations for the severity of election manipulation rely on principal-agent and coordination problems among low-level election-manipulating agents. The classic account holds that agents fear punishment if their patron loses the election, which causes manipulation to fall as competitiveness increases (Rundlett and Svolik Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016). However, this formalization overlooks the possibility that agents may face legal risks even if their patrons remain in office. To date there is no systematic study of judicial proceedings against individuals accused of violating electoral law; however, they are well documented by journalists and election monitors. For example, in Russia the ruling party found over 1,000 of its agents subject to judicial penalties after the 2016 election (Tikhonova Reference Tikhonova2016)—an outcome that is all the more remarkable given that Russia is a relatively low-competition regime, with relatively low de facto judicial independence (Linzer and Staton Reference Linzer and Staton2015). This suggests that principal-agent problems may be intensified as agents bear greater risk of legal exposure—a point that existing theory overlooks.

Theory: De Jure Independence, Strategic Pressure, and Election Manipulation

As discussed above, creating the formal space for judicial independence in nondemocracies includes risks as well as benefits for ruling parties. In particular, greater de jure independence increases opportunities for opposition-oriented actors to press their case in court, even when they believe they are unlikely to win. Opposition groups may take cases to court to raise publicity around an issue (Dotan and Hofnung Reference Dotan and Hofnung2005; McCann Reference McCann1994), to protest against the authorities (Dor and Hofnung Reference Dor and Hofnung2006), or to push the incumbent to make concessions between elections (Chernykh Reference Chernykh2014). Such strategic litigation can be especially useful for imposing a cost on the regime when the policy domain is an issue—like election fraud, or corruption—that the government cannot defend on the merits (Aydın-Çakır Reference Aydın-Çakır2014). For individual candidates, casting doubt on an election result in court can be a way of retaining political credibility for future races (Kerr and Wahman Reference Kerr and Wahman2021). As a result, multiple actors can have incentives to take election-manipulation cases to court, even if they expect the case to fail.

Strategic litigation of this sort is more likely when potential litigants observe favorable laws and constitutional provisions (Epp Reference Epp1998), including a more de jure independent judiciary. For example, the expansion of de jure reforms in China (Peerenboom Reference Peerenboom2010) widened the political opportunity structure for rights-based legal mobilization there (Nesossi Reference Nesossi2015). Similarly, the establishment of a de jure independent constitutional court in Egypt paved the way for opposition and civil society groups to challenge the government in court, often successfully (Moustafa Reference Moustafa2003). Opposition-minded groups will be more likely to go to court when they perceive courts to be more independent and powerful and more attainable allies than the executive (Schaaf Reference Schaaf2021), a judgement that de jure reforms are likely to inform. In other words, a positive de jure reform is itself a theoretically significant driver of antiregime legal mobilization, not just an easily observable proxy for more obscure judicial behavior.Footnote 4

An expansion in opposition legal mobilization is likely to lead to an increase in the number—if not the rate—of unfavorable decisions for the government, so long as judges have some incentive to rule against the ruling party. Judges may choose to do so because ruling against the government can build public trust in the judiciary (Kerr and Wahman Reference Kerr and Wahman2021; Yadav and Mukherjee Reference Yadav and Mukherjee2014), a political resource that judges may wish to cultivate (Helmke Reference Helmke2010; Staton Reference Staton2010). Moreover, judges may rule against election-manipulation defendants due to their own ideas about democracy (Hilbink Reference Hilbink2012) or due to a desire to build a reputation with nonstate judicial audiences (Kureshi Reference Kureshi2021). Finally, judges in nondemocracies may feel confident in ruling against government agents in low-stakes election manipulation cases, as they can fulfill their regime-legitimation function only by occasionally handing small setbacks to the regime.

Taken together, then, increased legal mobilization by opposition actors should lead to an increase in antigovernment rulings, so long as the government does not intervene to prevent them. As the consequences of negative rulings rise, intervention by the government becomes more likely (Ellett Reference Ellett2013; VonDoepp Reference VonDoepp2009). As the cost of electoral defeat is steep in nondemocracies—defeated leaders may find their assets or lives at risk (Epperly Reference Epperly2017)—ruling parties are more likely to take measures that undermine judicial independence in election-related cases when competition, and thus the downside risk of adverse rulings, is high (Popova Reference Popova2012). Cross-national research supports the idea that courts’ behavioral independence declines as political competition increases outside liberal democracies (Aydin Reference Aydin2013; Wang Reference Wang2020).Footnote 5

Whether election-related cases are sensitive and likely to draw pressure is thus context dependent. If the costs of negative rulings are minor for the ruling party, they may be outweighed by the regime-sustaining benefits of independent rulings. However, as these costs increase, the ruling party’s incentive to apply pressure in that domain grows. This pressure can be informal and case-specific, helping to preserve some benefits of judicial independence and to avoid provoking a public clash that might damage the government (Helmke Reference Helmke2010).

In the absence of pressure, more independent rulings by courts in election-manipulation cases can deter manipulation in two ways. First, ruling parties may seek to deny opposition groups the benefits of strategic litigation discussed above—greater visibility, an opportunity to attack the regime on an unpopular valence issue, etc.—by choosing to reduce the level of manipulation in the election. Ruling parties may be concerned that negative publicity may damage their popular legitimacy (Berman et al. Reference Berman, Callen, Gibson and Long2019; Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013; Kailitz Reference Kailitz2013; Moehler Reference Moehler2009; von Soest and Grauvogel Reference von Soest and Grauvogel2017), even if such damage falls short of mass protest, and choose to pull back on manipulation in order to minimize strategic litigation by their opponents.

In addition, building on the work of Rundlett and Svolik (Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016), legal risks are likely to figure into the calculations that low-level actors make about participating in election manipulation. Although that formal model assumes that election-manipulating agents run no risk of penalty if their patron wins the election, I argue that a higher risk of legal exposure may deter agents from engaging in manipulation even when incumbents retain office. Courts can hear charges against election officials for a variety of positive acts of election tampering, and they can also hear cases against ordinary individuals for engaging in vote-buying or voter pressure, voter impersonation, and multiple voting (Orozco-Henríquez, Ayoub, and Ellis Reference Orozco-Henríquez, Ayoub and Ellis2010). And, as the foregoing discussion illustrates, courts in nondemocracies can generate regime-sustaining benefits by ruling against ruling party agents at times—and regularly do so. The risk of being caught up in court proceedings can be expected to increase as opposition actors turn to more de jure independent courts, serving to deter some agents. This expectation is also consistent with the finding that harder-to-detect manipulation is concentrated in places where the opposition is more active (Harvey Reference Harvey and Mukherjee2020). Following the logic of coordination problems in Rundlett and Svolik (Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016), an increased risk of court proceedings that deters some agents from engaging in election manipulation can induce others to stand down as well; if some low-level actors choose not to participate in election fraud due to legal risk, a larger number may also shirk due to uncertainty around the success of the effort, leading to a larger-scale improvement in election integrity.

This mechanism is only likely to operate when governments regularly enforce rulings against their own agents. Nondemocratic governments enforce unfavorable rulings against their agents when the stakes for the regime are low because courts’ various regime-sustaining functions depend “upon some measure of real judicial autonomy” (Ginsburg and Moustafa Reference Ginsburg and Moustafa2008, 8); if they did not, courts could not improve the regime’s legitimacy, resolve intra-elite disputes, or provide accurate information about citizen discontent. As a result, courts in nondemocracies regularly rule in citizens’ favor when the stakes are low (Popova Reference Popova2012). For example, Hendley (Reference Hendley2017, 150) finds that in 2009 and 2011, Russia’s justice of the peace courts ruled in favor of the state only 50% of the time when it brought tax cases against citizens and ruled in favor of citizens fully 80% of the time when they were the plaintiffs; Peerenboom (Reference Peerenboom2002) finds similar results in China. Rulings against election-manipulating agents are likely to be enforced in at least some cases, as a result, so long as doing so in individual cases does not threaten the core interests of the regime (Murison Reference Murison2013). Indeed, courts in Russia ruled in favor of 47% of plaintiffs who alleged improper behavior by election commissions (including fraud allegations) after the 1999 election (Solomon Reference Solomon2004).

The theoretical argument can be summarized as follows. Governments in authoritarian regimes and electoral democracies create more de jure independent courts in order to capture multiple benefits: legitimation, information-gathering, dispute resolution, and the promotion of investment, among others (Moustafa Reference Moustafa2014). Even when the chances of winning cases are low, opposition groups take advantage of this opening in the political opportunity structure to impose costs of the regime and to bolster their own organizational resources. Judges who enjoy greater formal protections are thus more likely to hear cases from the opposition, leading to an increase in the number—and possibly the rate—of negative rulings for the regime in the absence of informal pressure from the ruling party. In the domain of election manipulation, increased costs of strategic litigation to the regime and increased legal risk to election-manipulating agents are both likely to lead to cleaner elections. When political competition is low, this lost manipulation is bearable to the regime. However, as electoral uncertainty increases, ruling parties will be more likely to bring their informal tools to bear on courts to secure favorable decisions in election cases. This pressure will reduce the effect of de jure independence on manipulation as competition increases.

Hypothesis 1: An increase in de jure judicial independence is associated with reduced election fraud when political competition is low but not when it is high.

A further implication of the theory can be tested by exploiting the fact that nondemocratic governments sometimes create special courts to ensure that politically sensitive cases are handled according to the ruling party’s wishes while allowing mundane matters to proceed through (more independent) ordinary courts (Fraenkel Reference Fraenkel1941; Hilbink Reference Hilbink2007; Moustafa Reference Moustafa2003; Reference Moustafa2007; Peerenboom Reference Peerenboom2002; Toharia Reference Toharia1975). The theoretical mechanisms summarized above only operate if electoral cases are heard in the ordinary courts. If victims of electoral malfeasance lack access to the regular courts (due to their lack of jurisdiction in electoral cases), increased independence for those courts should not drive increased legal mobilization. Moreover, if alleged perpetrators of election manipulation face consequences only from pliant specialized courts, increases in de jure independence for the general courts should not lead to a more open legal opportunity structure for the opposition or to increased risk for agents or the party.

Hypothesis 2: The effect posited in H1 should only be observed in cases without specialized electoral courts.

Finally, an alternative hypothesis can be drawn from judicial insurance theory (Epperly Reference Epperly2017; Reference Epperly2019) and strategic defection theory (Helmke Reference Helmke2002). In these theories of judicial independence—for distinct reasons—greater political competition in nondemocracies is understood to result in higher levels of de facto judicial independence. Under insurance models of judicial independence, nondemocratic governments promote judicial independence under competitive conditions to insulate the courts from government pressure should the opposition come to power. In the strategic defection model, high-court judges are more likely to rule against nondemocratic governments that appear threatened in order to gain favor with an incoming opposition government. In either framework, it might be expected that judges will rule more autonomously in election-related cases under conditions of greater competition, leading to reduced election manipulation.

Hypothesis 3: An increase in de jure judicial independence is associated with increasingly large reductions in election manipulation as competitiveness increases.

It is important to be clear that these expectations refer to illegal manipulation—such as falsification, ballot stuffing, and intimidation—in which judges can find individuals criminally or administratively guilty of violating election law. These are a substantively important set of tools for election management in nondemocracies (Calingaert Reference Calingaert2006), which are frequently an object of study as a result (e.g., Rundlett and Svolik Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016). Because vote-buying and voter pressure can be harder to observe than election fraud (Harvey Reference Harvey and Mukherjee2020) and may exist in ethical and legal gray areas (Kramon Reference Kramon2016; Nichter Reference Nichter2018)—thus making them harder for courts to address—I focus here on election fraud specifically.Footnote 6 Forms of electoral manipulation that rely on the law itself—such as structuring the electoral system to benefit ruling parties—though important, are likewise not considered here. Similarly, this theory is not expected to apply to cases where high courts are making the determination to annul an election after allegations of fraud—the extremely high stakes and visibility of such decisions are likely to lead judges to follow the logic of strategic defection (Helmke Reference Helmke2002). Last, due to the limited availability of tools for informally pressuring courts in liberal democracies, longer time horizons for rational politicians, and other features of liberal democracies, this theory is not expected to apply in such cases (Popova Reference Popova2010).

Data and Methods

These hypotheses are difficult to test using observational data due to likely endogeneity among political competition, judicial reforms, and electoral manipulation. For example, it could be that governments are more willing to engage in reforms when they face reduced ability to commit fraud (perhaps due to resource constraints). Strictly observational analysis of data would make it difficult to tease out the direction of the causal arrow between judicial reforms and election integrity. The research design described below seeks to more accurately determine the relationship between courts and election quality through preanalysis balancing of control and treatment groups.

To test these propositions, I draw on Version 7.1 of the V-Dem project (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman and Andersson2017). Because the theory applies to cases that hold multiparty elections but are not liberal democracies, I exclude countries where the regime holds single-party elections or no elections at all, as well as liberal democracies at the time of the election. The latter criterion is operationalized by excluding country-years coded as “competitive” under the competitiveness of participation variable from Polity. Doing so excludes country-years where “ruling groups and coalitions regularly, voluntarily transfer central power to competing groups,” and “competition seldom involves coercion or disruption” (Marshall, Gurr, and Jaggers Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2017). The resulting dataset contains electoral authoritarian regimes, hybrid regimes, and unconsolidated or electoral democracies. At the higher range of competitiveness, the dataset includes cases like post-Soviet Georgia, the Philippines in the 1990s and 2000s, and Venezuela in the 1990s. The low end of the range includes cases like postwar Portugal and post-Soviet Uzbekistan. Altogether, the dataset includes election years from 1944 to 2014, though most observations are from the post-Cold War period.Footnote 7 The results are shown to be robust to the binary coding scheme for democracy developed by Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland (Reference Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland2010) in an appendix (Table B.5).

Dependent Variable and Controls

I measure illegal electoral manipulation using the variable intentional voting irregularities taken from V-Dem. This variable is a measure of vote fraud and related forms of manipulation including multiple voting, ballot-stuffing, and falsification of results. As with other variables drawn from V-Dem, values for voting irregularities reflect the judgements of five or more expert coders. I use the measurement model output version of the variable, which aggregates the country experts’ ratings, takes disagreement and measurement error into account, and converts the ordinal scale responses from experts to an interval scale (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman and Andersson2017).Footnote 8

Explanatory Variables and Controls

Reforms that improve de jure independence are operationalized as a binary variable from V-Dem that captures enhancements to courts’ ability to control the arbitrary use of state power in the year prior to an election.Footnote 9 To take a relatively recent example, several East European postcommunist states undertook reforms to limit the influence of the elected government over judicial careers by transferring powers over appointment and dismissal from ministries of justice to more autonomous judicial councils (Coman Reference Coman2014). Such preelection reforms are not uncommon in nondemocratic cases: a positive judicial reform is recorded prior to 165 of the 1,009 election-year observations in the dataset.

Measures of de jure judicial independence are also available from the Comparative Constitutions Project (Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2005). The CCP dataset benefits from clear rules that enable precise coding of changes to a country’s constitutional judicial institutions, and certain selection and removal procedures appear to be jointly associated with increased behavioral judicial independence in nondemocracies (Melton and Ginsburg Reference Melton and Ginsburg2014). However, positive, preelection reforms to de jure independence are rare at the constitutional level—only thirteenFootnote 10 are observed for the country-years studied here—leading to a lack of common support across some mediator variables. As a result, the CCP measures are not used in the main analysis, but are used as robustness checks in the appendix (Table A.6). These models are substantively similar to the main results.

Political competition is the second explanatory factor. Because the margin of victory in the election itself cannot be used as a measure of competition—being an effect rather than a cause of electoral manipulation—I use three alternative measures meant to capture the degree to which incumbents face some uncertainty around election outcomes. All are lagged one year, so that they are not influenced by the results of the election year and do not contain information on election fairness overall. The first is drawn from the polyarchy index in V-Dem and captures the degree to which the conditions for political competition are present; in raw form this variable is a multiplicative index of variables measuring freedom of association, freedom of expression, suffrage, the presence of national elections, and the integrity of elections. To avoid spurious correlation with the dependent variable, I divide out this latter component; I call this variable political openness.

Next, I use a measure of legislative oversight of the executive, also from V-Dem, which codes the degree to which opposition parties in the legislature are able to exercise oversight against the wishes of the governing party (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman and Andersson2017). Consequently, it captures both the size and oppositional character of opposition parties in the legislature; a larger and/or more assertive opposition represents greater risk to the government compared with cases where parliamentary parties are opposition in name only (Reuter and Robertson Reference Reuter and Robertson2015). This is similar in its logic to the measure of political constraint used by Epperly (Reference Epperly2017), which is the third measure I employ. This variable captures the number of executive and legislative veto points, legislative alignment with the executive, and party fractionalization within the legislature (Henisz Reference Henisz2002). Higher scores on this variable indicate greater degrees of constraint, such as when a unified opposition party in the legislature opposes the executive.

I also include control variables that may help account for the severity of electoral manipulation. A dummy variable is used to control for executive elections, which may lead to higher levels of manipulation (Simpser Reference Simpser2013). I also include logged GDP per capita as a measure of economic development (Simpser Reference Simpser2013). A binary measure of the ability of international election monitors to observe the election is also included, as observers may affect the reported quality of the election by either reducing the occurrence of electoral manipulation or exposing it (Hyde Reference Hyde2011; Roussias and Ruiz-Rufino Reference Roussias and Ruiz-Rufino2018). In addition, I add a categorical measure of the nature of the electoral system, as majoritarian systems may be more likely to provoke fraud (Birch Reference Birch2007).Footnote 11 Last, I control for attacks on the judiciary—court packing, judicial purges, and negative de jure reforms that reduce the ability of the judiciary to constrain arbitrary state power in the year before the election. Each of these variables is taken from the V-Dem dataset. After preprocessing, discussed below, the data are analyzed using weighted ordinary least squares with country fixed effects.

Preprocessing and the Selection Model

Using standard regression analysis to understand the relationship between judicial independence, courts, and electoral manipulation runs the risk of producing biased results due to endogeneity and confounding, as discussed above. Instead, I use preprocessing methods that weight observations to balance treatment and control groups along a set of covariates, making treatment conditionally independent of those variables. This allows researchers to better identify casual relationships (Hirano, Imbens, and Ridder Reference Hirano, Imbens and Ridder2003; Ho et al. Reference Ho, Imai, King and Stuart2007; Rosenbaum and Rubin Reference Rosenbaum and Rubin1985); however, they can also increase bias if the selection model is misspecified (Arceneaux, Gerber, and Green Reference Arceneaux, Gerber and Green2006). To reduce this risk, I make use of techniques that do not require iterative checking of the change in balance produced by different selection models (Hainmueller Reference Hainmueller2012; Imai and Ratkovic Reference Imai and Ratkovic2014)—thus avoiding cherry-picking—and by including measures of theoretically important predictors of the treatment in the models.

The primary method of preprocessing and analysis presented here is entropy balancing, which assigns weights to control observations such that the weighted means of covariates match across treatment and control groups while minimizing the distance between the individual weights and the default expectation of equal weighting (Hainmueller Reference Hainmueller2012). This method has been shown to be doubly robust to misspecifications of either the selection or outcome models (Zhao and Percival Reference Zhao and Percival2016). As an alternative preprocessing technique, discussed in the appendix, I also weight observations using covariate-balancing propensity scores (Imai and Ratkovic Reference Imai and Ratkovic2014), with similar results (Table A.3).

To balance treatment and control groups, it is important to correctly specify the covariates of the treatment variable. This is especially important in this setting, where the incumbent government has at least some control over selection into treatment—increasing de jure judicial independence—and over the integrity of its elections. First, I balance on the binary variable transitional election, which records whether the upcoming election is part of shift toward multiparty elections. This is an important step, as some positive reforms may occur as part of a broader regime change, whereas others may be adopted by authoritarian governments seeking to gain legitimation and other benefits. In particular, it is possible that at a moment of regime transition, an insurance logic will incentivize outgoing ruling parties to permit the creation of more formally dependent courts (Magalhães Reference Magalhães1999), at the same time that their manipulative capacity declines. Balancing on transitional election helps control for this possible source of confounding.

I also include variables that capture sources of judicial independence. All variables described below lag one year behind any preelection judicial reform. These are the age of the regime in years (Boix, Miller, and Rosato Reference Boix, Miller and Rosato2013) because younger democracies may be more prone to changes in judicial independence (Helmke and Rosenbluth Reference Helmke and Rosenbluth2009), the level of economic development (Helmke and Rosenbluth Reference Helmke and Rosenbluth2009), the openness of the media environment (Staton Reference Staton2010) and of the political system (Ramseyer Reference Ramseyer1994), the degree of concentration of power in the executive, and the extent of horizontal competition between the executive and the legislature (Epperly Reference Epperly2019; Helmke Reference Helmke2012; Randazzo, Gibler, and Reid Reference Randazzo, Gibler and Reid2016). I also include measures of high-court independence and low-court independence from V-Dem, as well as the latent judicial independence measure developed by Linzer and Staton (Reference Linzer and Staton2015). This allows the models to capture the estimated effect of a positive de jure reform, independent of the pre-reform level of de facto independence.

The preprocessing step also includes the relevant measure of political competition for each regression model, lagged by two years. Crucially, this helps reduce the risk of confounding based on competitiveness as a common cause of judicial reform and election fraud. By including these variables in the preprocessing phase, the treatment variable is made conditionally independent of political factors that might incline a government to empower its courts and also influence election manipulation, such as rising levels of political openness. Balance statistics are provided in the appendix (Table A.1).

Two other potential confounders are considered in the appendix (Tables A.8 and A.9), due to high missingness; both sets of models support the main findings. First is the preelection legislative seat share of the governing party (Cruz, Keefer, and Scartascini Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2017), as governing parties with a slimmer majority may increase the formal independence of the judiciary as an insurance policy should they enter the minority (Epperly Reference Epperly2019) or seek to intensify their control over the courts to forestall losing power (Aydin Reference Aydin2013; Popova Reference Popova2010). Similarly, more dominant parties are likely able to deliver higher levels of manipulation (Rundlett and Svolik Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016; Simpser Reference Simpser2013), though competitiveness has also been associated severe manipulation (Lehoucq Reference Lehoucq2003). Second, it could be that governments that are already ineffective at generating election manipulation are more likely to positively reform their judiciaries, leading to a spurious correlation between de jure reforms and reduced manipulation. To account for this, I add a lagged measure of manipulation to the selection model. Table 1 lists the variables used in the preprocessing phase, along with their sources.

Table 1. Variables Used in Preprocessing Stage

Note: All variables except preelection seat share and prior election fraud lagged by two years.

Results

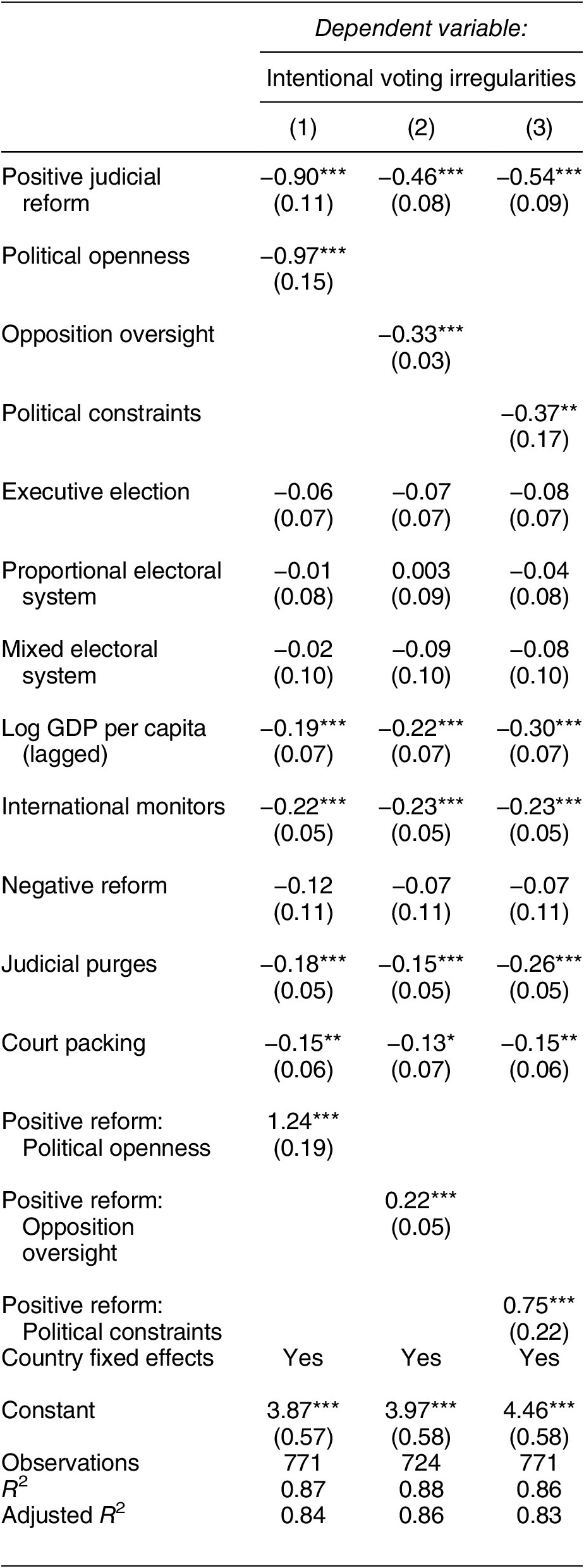

The results of these models are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1. As Figure 1 shows, an improvement in de jure judicial independence is associated with a reduction in intentional voting irregularities only at low levels of political competition, across all three measures. This is supportive of Hypothesis 1; Hypothesis 3, which predicts a negative slope for the marginal effects due to an insurance logic or strategic defection, is not supported.

Figure 1. Marginal Effects of a Positive Judicial Reform on Intentional Voting Irregularities (Models 1–3)

Note: Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2. Weighted Ordinary Least Squares Models of Election Fraud (Entropy Balanced Weights)

Note: All variables one-year lagged except executive election, proportional electoral system, mixed electoral system, and international observers. *p< 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

The size of the effect of a positive judicial reform is substantively large, even at modestly low levels of competitiveness. Using figures from Model 2 and holding opposition oversight constant at its first quartile—representing a typical more authoritarian case—a positive judicial reform results in a marginal decrease in intentional voting irregularities of -0.63—which amounts to roughly 12% of the overall range of the voting irregularities variable. A comparison with the marginal effect of opposition oversight using the same model shows the substantive significance of such a shift. Holding judicial reform constant at zero, an increase from the first quartile to the mean of oversight results in a smaller reduction in fraud: -0.21. That a positive judicial reform in the year before an election can have an effect size that is three times larger than that of a major shift in political competition (as measured by the size and assertiveness of the parliamentary opposition) is notable given the prevalence of competitiveness as a predictor of electoral fraud in earlier research (Lehoucq Reference Lehoucq2003).

Moreover, the models meet important tests of viability that have been identified in recent methodological work on interaction effects. Confidence intervals have been adjusted in Figure 1 to account for the greater false-positive rate that can occur when testing for significance multiple times (Esarey and Sumner Reference Esarey and Sumner2017), and the results are statistically significant using both the “crosses zero” heuristic and the “compare extremes” heuristic for interpreting marginal effects (Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2018).Footnote 13 In the appendix, I also demonstrate that the procedures advocated by Hainmueller, Mummolo, and Xu (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019) for checking the appropriateness of a linear multiplicative interaction model are satisfied in this case (Figure A.1).

Hypothesis 2 predicts that the relationships illustrated in Figure 1 will not occur in cases where there are specialized electoral courts. To test this, I replace the interaction terms in Models 1 through 3 with a three-way interaction, adding an indicator for the presence of an electoral court. Due to space constraints, Figure 2 presents these results; the full regression table is available in the appendix (Table A.7). In the figure, the left panels represent cases without electoral courts, whereas the right panels represent those that do. In all three models, there is a reduction in manipulation in cases after judicial reforms (dashed lines) where the general courts handle electoral issues and when competition is low (supporting H1). In settings with specialized electoral courts, there is no such reduction (supporting H2).

Figure 2. Marginal Effects of Judicial Reform on Intentional Voting Irregularities

Note: Dashed lines indicate preelection judicial reform; solid lines represent no reform. Panels marked 0 indicate no electoral court, panels marked 1 represent cases with electoral courts. Control variables held at the mean. See Appendix Table A.7.

Discussion

Greater de jure judicial independence appears to improve election integrity in the “toughest” cases, where competition is most limited. The results shown here are consistent with the theory that de jure reform creates greater opportunities for legal mobilization, resulting in reduced election manipulation when the ruling party has limited incentives to intervene—an effect which declines as competitiveness compels ruling parties to apply pressure to protect their election-manipulation efforts.

How confident can we be in this result given the tangled relationship between election fraud, competition, and the courts? There are both theoretical and model-based reasons to be confident that the level of pre-reform competition is not a confounder for the results here. First, prior work does not show that competition is associated with greater de jure independence in nondemocracies (Epperly Reference Epperly2019; Staton, Reenock, and Holsinger Reference Staton, Reenock and Holsinger2022). Second, balancing on pre-reform level of competition and transitional elections helps control for the possibility of such an effect. Additional robustness checks in the appendix show that the results are robust to different sampling frames and selection models. Finally, country fixed effects in all models help reduce the risk of omitted variable bias. Within the limits of observational data on interconnected political processes, the results of this research design provide strong evidence that greater de jure independence can reduce electoral fraud substantially in low-competition settings but have no effect in more competitive ones.

Although this theory specifically concerns election manipulation, it offers insights for the broader debate on the relationship between courts’ de jure and de facto independence. Studies in that literature often rely on general measures of de facto independence, like Linzer and Staton’s (Reference Linzer and Staton2015) measure of latent judicial independence. This approach can obscure the fact that courts may be permitted to rule independently on the economic issues captured by some indicators in latent judicial independence (for example), but come under pressure in more sensitive political cases captured by other indicators. Such patterns may help explain the mixed findings in the literature.

This model offers a framework for moving this debate forward by predicting which policy domains will allow for de facto independence to grow out of de jure reforms. For de jure reforms to be effective in a particular domain, as this article shows, four scope conditions must be met: (a) there must be access to the de jure independent courts in that domain; (b) there must be actors with incentives to go to court against the state, even if the odds of winning are low; (c) judges must have an incentive to rule against the government at times; and (d) the ruling party’s incentive to intervene must be low. In the electoral context, it is likely that conditions B and C hold generally: politicians and civil groups have multiple incentives to go to court, even when defeat is all but assured; judges have incentives to rule against the ruling party at times, if only to uphold courts’ broader regime-sustaining benefits. The first and fourth conditions are thus more likely to be decisive; they are met here when competitiveness is low and there are no special electoral courts; they fail when electoral cases are heard in special courts or as competitiveness increases.

In other policy domains, these scope conditions may apply differently. In the domain of human rights violations, for example, victims or their families may have no incentive to go to court, fearing further persecution. This failure of scope condition B could explain why most de jure institutions identified by Keith, Tate, and Poe (Reference Keith, Tate and Poe2009) are not associated with reductions in human rights abuses. Likewise, while competitiveness is a marker of the ruling party’s incentives to intervene (scope condition D) in electoral cases, it may not be relevant in other domains. For example, in economic domains courts could come under pressure due to fragmentation within the ruling elite (Bolkvadze Reference Bolkvadze2020) rather than outside it or if economic interests outside the regime are relatively powerful (Ma Reference Ma2017). This does not mean that variables like latent judicial independence should be avoided in empirical work; rather, that for the specific question of how de jure reforms translate into behavioral independence, more specific measures may be needed.

These findings also have implications for existing theories of electoral malfeasance. Chernykh and Svolik (Reference Chernykh and Svolik2015) argue in their formal model that independent courts can deter manipulation when political competition is high by exposing information about fraud and thus increasing the risk of protest. Protest risk is commonly posited as the primary deterrent to election manipulation, especially in formal work (Little Reference Little2012; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2010). However, these results do not lend support to that proposed causal mechanism for two reasons. First, the effect of a positive de jure reform is independent of alternative sources of information, a measure of which is included in the preprocessing phase. Second, they show that courts reduce the likelihood of fraud in settings of low partisan contestation and low political openness—settings where protest is also unlikely (Beaulieu Reference Beaulieu2014; Simpser Reference Simpser2013; Trejo Reference Trejo2014). Models presented in an appendix (Figure B.3) confirm that, if anything, judicial reforms make postelection protest less likely when fraud is high. As a result, the observed effect of positive judicial reforms on fraud is unlikely to be mediated by protest risk.

As an alternative to protest-risk theories of electoral manipulation, principal-agent theories highlight the risks faced by low-level agents who do the work of tampering with elections. The negative relationship between formal judicial independence and electoral manipulation in uncompetitive settings suggests that agents may have consequences to fear even if their patron remains in office. Agents fearful of punishment may refuse to engage in electoral manipulation even if their political patrons would benefit (Rundlett and Svolik Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016). By increasing the risk that individual election-manipulating agents will be exposed and punished—even following a ruling party victory—de jure reforms may worsen the principal-agent problem and make it harder for ruling parties to recruit willing agents. Support for H2 also bolsters this interpretation; dependent special courts shield agents from risk but should do little to reduce protest risk because opposition groups can still use the electoral courts to publicize their claims, even if such courts are not fully independent (Chernykh and Svolik Reference Chernykh and Svolik2015). This understanding of agent risk is a theoretically significant advancement on the model developed by Rundlett and Svolik (Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016), who assume that leaders will protect their agents if elected. Broadly speaking, it may help explain why seemingly strong ruling parties sometimes fail to deliver adequate election manipulation and how opposition groups try to raise the cost of manipulation for low-level actors, and it indicates that policy reforms can improve election integrity even in uncompetitive areas.

Other tests of the implications of this framework are provided in the appendix. Modeling effects over time shows that improvements in election quality in low-competition settings fade in subsequent elections (Figure B.1), in keeping with the prediction that increased competition will yield increased pressure on courts. On the one hand, this may appear to limit the general relevance of this finding. However, it confirms the general thesis that the relationship between judicial independence and election integrity is a dynamic one. Moreover, it points toward some practical implications of this research for rule-of-law promoters (Carothers Reference Carothers2006). In the electoral domain, de jure reforms can have limited payoff for democracy promotion in the short run—pressure from ruling parties, once applied, can weaken the democratizing effects of judicial reform. Instead, they show that democracy promoters and good-government advocates may wish to emphasize investments in capacity building for legal civil-society groups and raising legal consciousness, especially in noncompetitive cases. Given the increasing turn toward formal judicial independence in many nondemocratic countries—evidenced, in part, by the large number of preelection reforms identified here—policies that improve the capacity for legal mobilization in nondemocracies once the regime embarks on reforms have the potential to improve election integrity in places that may have been overlooked using prior models. Finally, models in the appendix show that de jure reforms increase the risk of a democratic transition substantially in the next election for low-competition cases (Figure B.2), consistent with the idea that reforms lead to reduced manipulation and surprisingly good outcomes for opposition groups—an example of democratization by incumbent miscalculation (Treisman Reference Treisman2020). In fact, the risk of democratic transition effectively doubles after de jure reform in such cases. Consequently, these results offer both broader theoretical insights on the relationship between de jure and de facto judicial independence, as well as practical implications for the cases at hand.

Conclusion

Nondemocratic regimes can generate a variety of benefits from granting their courts a degree of independence. To accomplish this, nondemocracies have adopted many of the same de jure institutions of judicial independence found in democracies, just as many nondemocracies have adopted the institutions of multiparty elections. Nevertheless, there are varying predictions about the effect of judicial independence on election manipulation in nondemocracies. This paper sets out a new theory of this relationship, which argues that by increasing the opportunities for legal mobilization by opposition actors, de jure reforms can lead to reduced election fraud in noncompetitive settings. This effect is attenuated as competition increases and governments face stronger incentives to pressure the courts. Support for these predictions is found using a large cross-national sample and preprocessing techniques to improve causal inference. The findings are contrary to the predictions of protest-oriented models of election fraud (Chernykh and Svolik Reference Chernykh and Svolik2015) and the standard principal-agent model of manipulation (Rundlett and Svolik Reference Rundlett and Svolik2016), and they go beyond the predictions of strategic pressure theory (Popova Reference Popova2012).

These results improve our understanding of illegal election manipulation by implying that election-manipulating agents can face risks even if their patrons win the election and remain in power and that these risks can be exacerbated by de jure institutions of judicial independence. They indicate that the risk of mass protest may be overemphasized as a deterrent to manipulation, relative to more broad-based explanations like the modified principal-agent model and ruling parties’ fear that manipulating elections may induce low-level reductions in regime legitimacy. Substantively, the results have implications for nondemocracies and democracies at risk of backsliding alike. For nondemocracies, they show that de jure reforms that make investigation and prosecution more likely can generate real improvements in election quality. For democracies at risk of backsliding, this finding highlights the importance of judicial independence in sustaining election integrity.

Finally, the scope conditions of this model may provide insights for future research on the connections between de jure and de facto judicial independence in nondemocracies. This model predicts that the effect of de jure reforms on judicial behavior is jointly contingent on the existence of constituencies with an incentive to turn to the courts (even when the odds of prevailing are low) and on low incentives for the government to apply selective pressure on the courts. The effect of de jure institutions on judicial behavior is thus likely to vary according to the issue domain as well as the surrounding context. This suggests that future research on this question may benefit from focusing on issue domains, legal constituencies, and ruling-party incentives rather than on general concepts and measures of de facto independence.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000090.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/9HXKRA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article was prepared in part while the author held a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Wisconsin-Madison with the Wisconsin Russia Project, sponsored by Carnegie Corporation of New York. The author would like to thank the participants of the Comparative Working Group at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Kathryn Hendley, Graeme Robertson, and several anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback on this project.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author affirms this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.