In this article, we examine how Americans’ attitudes about masculinity influenced their electoral behavior in 2016. Using data from PRRI's 2016 White Working Class Survey, we consider how views on whether American society has grown “too soft and feminine,” a concept we characterize as gendered nationalism, factored into the 2016 presidential vote choice. Past work on gender attitudes and political behavior has focused largely on sexist beliefs about gender relations (Cassese and Barnes Reference Cassese and Barnes2018; Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2019), on voters’ self-identified masculinity and femininity (Bittner and Goodyear-Grant Reference Bittner and Goodyear-Grant2017; McDermott Reference McDermott2016), and on voter preferences for masculine leadership in politics (Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2011; Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016). Collectively, this body of literature suggests that beliefs about gender play a significant role in candidate evaluation and vote choice. Our project diverges from this work by focusing on beliefs about the gendered nature of American society as a whole—a sense of whether society is “appropriately” masculine or has grown too soft and feminine. Our results illustrate that voters think about American society in gendered terms and that these beliefs shape their electoral behavior.

We analyze gendered nationalism in the context of the 2016 US presidential election. Although all political candidates, both male and female, must navigate gender in their campaigns to a certain extent (Dittmar Reference Dittmar2015), Trump's bid for the White House was notable given that he faced the first female major party nominee as his opponent. Moreover, Trump routinely chastised female reporters, mocked the appearance of his only woman primary opponent Carly Fiorina, and questioned whether Hillary Clinton had the “fortitude, strength, and stamina” to run the country in political ads. He also called her a “nasty woman” during one of their debates (Sexton Reference Sexton2016). Trump's own past behavior toward women was also a campaign issue: Trump both denied allegations that he made unwanted sexual advances to more than a dozen women accusers and apologized for his “locker room talk” in a leaked Access Hollywood audiotape in which he bragged about his ability to sexually assault women thanks to his fame. Rife with “alpha male” appeal (Deckman Reference Deckman2016b), Trump's campaign described then-president Barack Obama as weak and ineffectual, even to the point of praising Russian strongman President Vladimir Putin, who, according to Trump, was “far more of a leader than our president has been” (Friedman Reference Friedman2016). The salience of overtly chauvinistic language and behavior make this election an ideal one to study regarding how attitudes about masculinity shaped Americans’ voting decisions.

Our analysis of the origins of gendered nationalist beliefs in 2016 shows that party, gender, and class shaped the endorsement of gendered nationalism: Republicans, men, and members of the working class were more likely to support gendered nationalist views. Further, voters with a college degree were more likely to oppose gendered nationalism. Our analysis of vote choice shows that gendered nationalist attitudes were strongly and statistically linked to the probability of voting for Donald Trump, and that these attitudes also had implications for the gender gap in vote choice. Once we account for gendered nationalism attitudes, the gender gap in support for Donald Trump is no longer statistically significant. Our research adds to the growing scholarly evidence that gendered beliefs are likely to have a bigger impact on American political behavior than voter gender alone. It also demonstrates that beliefs about gender are multifaceted and complex, extending beyond conventional measures of sexism, traits, and stereotypes.

THE IMPACT OF MASCULINITY AND FEMININITY ON AMERICAN POLITICAL BEHAVIOR

Political scientists have long examined gender differences when it comes to American political behavior. These gender-gap studies have examined how and why women and men differ when it comes to vote choice (e.g., Box-Steffensmeier, De Boef, and Lin Reference Box-Steffensmeier, De Boef and Lin2004; Carroll Reference Carroll, Carroll and Fox2006), partisanship (Kaufmann and Petrocik Reference Kaufmann and Petrocik1999; Ondercin Reference Ondercin2017), public opinion (Barnes and Cassese Reference Barnes and Cassese2017; Norrander and Wilcox Reference Norrander and Wilcox2008; Schlesinger and Heldman Reference Schlesinger and Heldman2001), and political participation more generally (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001). Although studies consistently find that women are more likely to identify as Democrats and that men are more likely to identify as Republican, and concurrently, that women hold more liberal views than men on a variety of policy positions, American women are far from politically monolithic, and they vary considerably when it comes to how their own gender shapes their political thinking and behavior (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2016; Deckman Reference Deckman2016a). For instance, prior studies that focused more specifically on the impact of feminism as a factor in explaining political behavior have yielded inconsistent results. Although feminist consciousness is strongly correlated with liberal values and policy preferences, this correlation works similarly for women and men (Cook and Wilcox Reference Cook and Wilcox1991). Moreover, few studies have found that feminist attitudes are consistent in predicting men and women's vote choices (Kaufmann and Petrocik Reference Kaufmann and Petrocik1999). Thus, gender consciousness (i.e., the notion that women have similar views and outlooks based on their shared experiences) has never been a principle that unites women voters in the same way that racial consciousness has united voters of color (e.g., Burns and Kinder Reference Burns, Kinder and Berinsky2012).

How conceptions of masculinity and femininity, apart from one's basic identification as male or female, shape Americans’ political choices, however, is less well understood. In this area, Monika McDermott's work (Reference McDermott2016) is an important exception. Her book Masculinity, Femininity, and American Political Behavior considers how citizens’ gendered personalities shape their political predispositions. McDermott argues that “masculinity and femininity are distinct personality traits that influence individuals’ social attitudes and behavior” (4). Gendered personality traits differ from sex differences, which are biological, and stem more from societal expectations of men and women. She writes:

The masculine dimension encompasses traits that were once associated with the male role of family provider. Masculine individuals are those who are independent, aggressive, competitive, and willing to take risks, among other traits. Femininity, in contrast, is made up of the personality traits expected of the traditional role of mother and caretaker. Individuals with feminine personalities are tender, affectionate, and sympathetic (4).

Although gendered personality traits are cohesive concepts, they do not perfectly overlap with identification as male or female. In fact, significant portions of the population have gendered personality traits that are not linked to their biological sex. McDermott (Reference McDermott2016) finds that citizens with higher levels of masculine traits are more likely to identify with the Republican Party and vote for Republican candidates whereas femininity among Americans increases their propensity to identify with and vote for Democrats, regardless of their biological gender.

Bittner and Goodyear-Grant (Reference Bittner and Goodyear-Grant2017) uncover a less straightforward relationship between gendered traits and political thinking in a series of surveys of Canadian voters. Rather than relying on individuals’ responses to questions about where they rank on a variety of masculine or feminine traits, Bittner and Goodyear-Grant asked respondents to place themselves on a continuum from 100% masculine to 100% feminine. Roughly 38% of Canadian women rated themselves as 100% feminine, and staunchly feminine women held more conservative attitudes on a range of policy issues, especially social issues such as abortion or same-sex marriage, compared with women who identified themselves as mostly (but less than 100%) feminine. Both men who described themselves as 100% masculine or mostly masculine consistently expressed more conservative positions than women overall. The important takeaway of this study is that these traits are linked to historical “ideal” expectations of the sorts of traits that men and women should hold in society, and they continue to linger despite changes in the actual roles of men and women in society (Prentice and Carranza Reference Prentice and Carranza2002).

GENDER AND NATIONALISM

Rather than focus on voters’ sense of their own masculinity and femininity, we consider whether voters characterized American society as masculine or feminine and whether this macro-level gendering, or gendered nationalism as we call it, had political implications in the 2016 presidential election. As defined by Nagel, nationalism involves “beliefs about the nation—who we are, what we represent—[that] become the basis and justification for national actions” (Nagel Reference Nagel1998, 248). The relationship between gender norms, masculinity, and nationalism has often been overlooked historically because of the private/public domain that situated women's role in the family and away from public life (Pateman Reference Pateman1988) despite of course women playing crucial roles in what Yuval-Davis (Reference Yuval-Davis1993) calls the “biological, cultural, and political reproductions of national and other collectivities” (630). Others have gone further, however, to argue that masculinity and masculine ethos are critical to understanding nationalism (Nagel Reference Nagel1998), including Cynthia Enloe (Reference Enloe2014), who argues that nationalism has its roots in “masculinized memory, masculinized humiliation, and masculinized hope” (45). Despite the rhetoric prevalent in democracies that aspire to equality for all, many have argued that the concept of nation remains “emphatically, historically, and globally, the property of men” (Mayer Reference Mayer and Mayer2002, 1).

However, little research empirically demonstrates a linkage between masculine/feminine attitudes, nationalism, and political behavior in the United States. One exception is research conducted by Van Berkel, Molina, and Mukherjee (Reference Van Berkel, Molina and Mukherjee2017), who find that both men and women consider masculine traits as more prototypically American than female traits, and that men are more likely to report higher levels of nationalism than women. Women are also less likely to identify with the nation when nationalism is constructed in masculine terms, yet both men and women typically list men rather than women as exemplars of “true Americans,” which they argue may disadvantage women as political leaders. Moreover, gendered traits are applied not only to national identity but also to party identity, and in some ways the two might be reinforcing. For example, Winter's (Reference Winter2010) longitudinal analysis of ANES data shows that Americans are increasingly likely to link masculine traits with the GOP and feminine traits with the Democratic Party explicitly—a finding he replicated with experimental research that shows such linkages are also implicit. In this respect, rhetoric that speaks to national masculinity might be especially effective when it comes from Republican candidates and is consistent with Republican voters’ expectations about Republican leadership. Our work ties some of these threads together by considering how Americans’ views on masculinity in society affect political choices in a presidential election that was unusually rife with gendered themes. Using data from PRRI's 2016 White Working Class Survey, we consider their question that asks respondents the extent to which America has grown “too soft and feminine.” With respect to vote choice, we expect that in 2016 Americans who viewed the nation as becoming too soft and weak found overtly masculine campaign themes employed by Donald Trump appealing. At the same time, we suppose that those who rejected gendered nationalism were likely more inclined to vote for Hillary Clinton, who represented a nontraditional or less prototypical choice for president.

BELIEFS ABOUT GENDER AND VOTE CHOICE IN 2016

Existing scholarship on gendered themes in the 2016 presidential election has focused primarily on the role of sexism in shaping voters’ choices rather than gendered attitudes toward the nation as a whole, and our project addresses this oversight in the literature. The sexism literature suggests that voters who held traditional views about gender roles or explicitly endorsed hostile sexist views were more likely to vote for Donald Trump, even when controlling for party and sex (Bock and Byrd-Craven Reference Bock and Byrd-Craven2017; Cassese and Barnes Reference Cassese and Barnes2018; Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2019; Junn Reference Junn2017; Schaffner, McWilliams, and Nteta Reference Schaffner, MacWilliams and Nteta2018; Valentino, Wayne, and Oceno Reference Valentino, Wayne and Oceno2018).

Certain voter characteristics have been associated with whether voters endorsed hostile sexism, and these same factors might account for variation in gendered nationalism.Footnote 1 Class and education are major factors contributing to men and women's beliefs about gender, including hostile sexism. The tendency to endorse hostile sexism and to reject the idea that women face discrimination in American society is especially pronounced among white working-class women and is significantly less pronounced among women with a college degree (Cassese and Barnes Reference Cassese and Barnes2018). This finding is consistent with past research suggesting that low-income women are more economically dependent on men and that they tend to adopt traditional perspectives on gender roles that are very similar to those held by working-class men (Baxter and Kane Reference Baxter and Kane1995; Legerski and Cornwall Reference Legerski and Cornwall2010). By contrast, college-educated women hold more distinctively liberal views and diverge more from their male counterparts with college degrees.

Of course, class also played an important role in shaping men's political behavior in 2016. The notion that Donald Trump's hypermasculine campaign rhetoric resonated most with working-class men was a common explanation for his victory (e.g., Katz Reference Katz2016). This account of men's voting behavior fits research suggesting this group of men is distinctly wedded to masculine notions of leadership and strength. White working-class men often display a hypermasculine ethos that asserts their strength, stamina, and dominance over women (and other marginalized social groups) as a reaction to their own feelings of marginalization (Connell Reference Connell2001; Embrick, Walther and Wickens Reference Embrick, Walther and Wickens2007). This form of working-class masculinity is often linked to accounts of the group's alienation from the “new economy,” which is more service-based and adheres to a more feminine workplace culture (e.g., Nixon Reference Nixon2009).

In the analysis that follows, we have considered whether class and educational attainment shape men and women's endorsement of gendered nationalism, with implications for their vote choice in 2016. Specifically, we tested the following hypotheses:

H1:

Gendered nationalism is more common among men compared to women.

H2:

Gendered nationalism is more common among working-class men and women than among men and women with other socioeconomic class identifications.

H3:

Gendered nationalism is less common among men and particularly women with a college degree compared to men and women with lower levels of educational attainment.

In terms of the implications of these beliefs for political behavior, we pose two additional hypotheses:

H4:

Voters who endorsed gendered nationalism were more likely to vote for Donald Trump in 2016.

H5:

The gender gap in this vote choice will be largely explained by gender differences in gendered nationalism.

DATA AND METHOD

To examine the sociodemographic correlates of gendered nationalism and its impact on the presidential vote in 2016, we have analyzed the 2016 White Working Class Survey, a nationally representative survey of adult Americans conducted jointly by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) and The Atlantic right after the 2016 presidential election.Footnote 2 PRRI asked all voters whether they strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, or strongly agree that American society has become too soft and feminine. We use responses to this item as our measure of gendered nationalism.

We first consider how gendered nationalist beliefs are distributed among voters based on their gender, class, and levels of educational attainment to see whether these beliefs coincide with common campaign narratives about Donald Trump's bases of support. In doing so, we test H 1 through H 3. We then turn to multivariate analysis and test the hypothesis that gendered nationalist beliefs, above and beyond these demographic characteristics, predict support for Donald Trump (H 4). We then examine how gendered nationalist beliefs and voter gender jointly influence vote choice. Using mediational analysis, we test the hypothesis that gendered nationalism underlies the gender gap in vote choice (H 5).

WHO THINKS THE UNITED STATES IS TOO SOFT AND FEMININE?

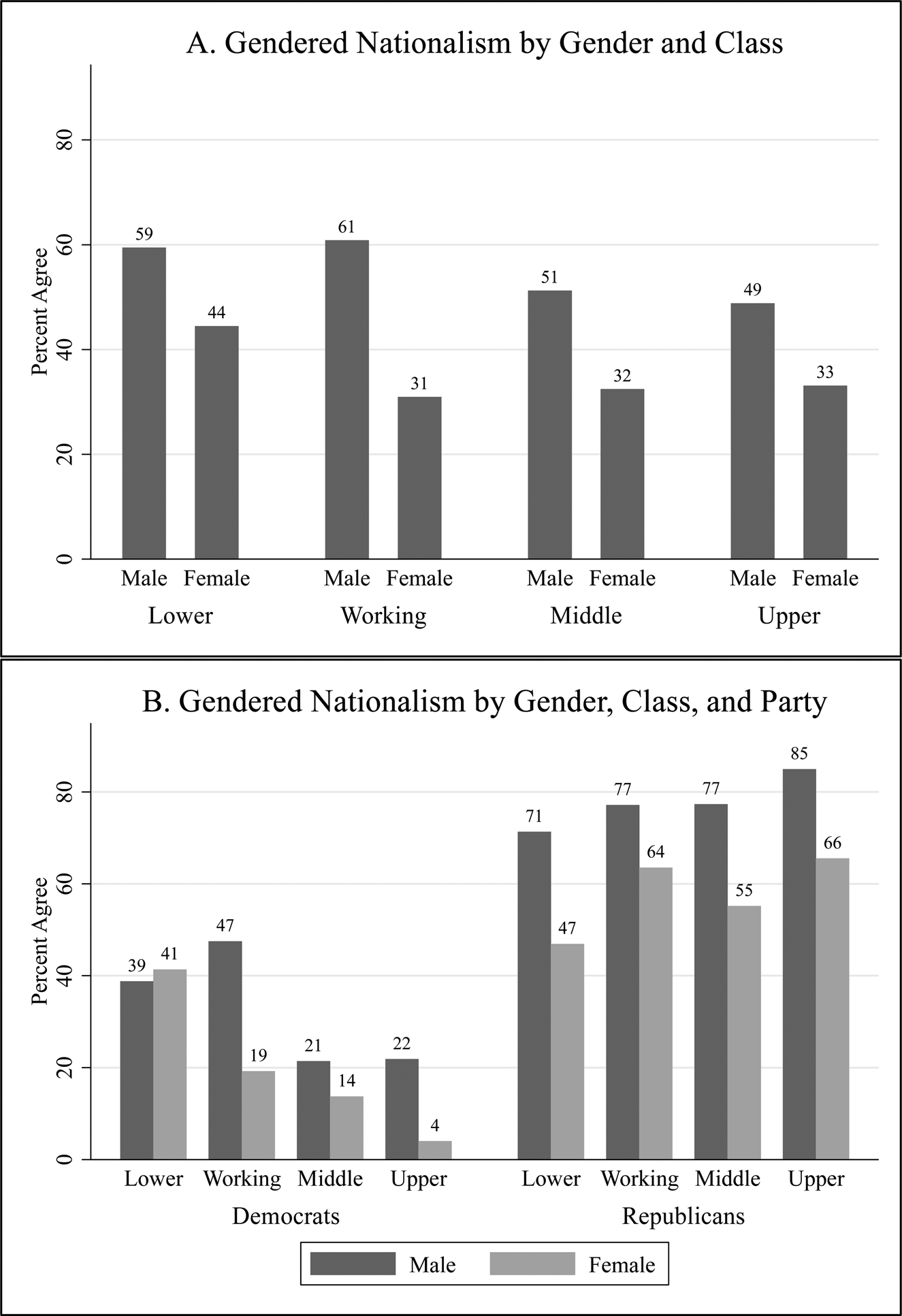

A substantial portion of American voters (45%) agrees that American society has grown too soft and feminine. To evaluate our expectations about the distribution of gendered nationalism beliefs across different kinds voters, we compare endorsement of the idea that the United States has become too soft and feminine across groups of survey respondents based on their gender, class, education, and party. We dichotomize responses to the “soft and feminine” question and compare the percentage of people in each group who provided “somewhat agree” or “strongly agree” responses to those who provided “somewhat disagree” or “strongly disagree” responses. Our first hypothesis is that gendered nationalism is more common among men relative to women. Overall, 56% of men agreed that the United States has grown too soft and feminine compared to only 34% of women—a difference that is statistically significant at the p < .001 level. Thus, H 1 is strongly supported. Of course, gender intersects with other social and demographic characteristics that create cross pressures on men and women's political thinking (e.g., Barnes and Cassese Reference Barnes and Cassese2017). Figure 1 illustrates support for gendered nationalism among men and women based on their self-identified economic classFootnote 3 (panel A) and party identification (panel B). We hypothesized that gendered nationalism is most common among working-class men and women (H 2). Panel A shows mixed support for H 2. Gendered nationalism beliefs were most common among working-class men (and nearly as common among lower-class men), with a gap of approximately 10% between these men and those identifying as middle or upper class. Across all class identifications, women were less likely to endorse gendered nationalism compared to men; but these beliefs were most common among women who self-identified as lower class, with no appreciable differences among women in the working, middle, or upper classes.

Figure 1. Relationships between class identification and gendered nationalism. Data are the percentage of respondents who somewhat agreed or strongly agreed with the “too soft and feminine question.” Survey weights have been applied.

Panel B elucidates the role of party identification, comparing survey respondents who identified as Democrats and Republicans based on their class and gender identifications. In the figure, the partisan divide in gendered nationalism is quite pronounced, with gender and class differences largely swamped by partisan ones. Among Democrats, working-class men stand out as the most supportive of the idea that the United States has grown too soft and feminine, consistent with H 2 and the narrative that this group has a distinctive orientation to masculinity. However, this is not matched by working-class women, among whom support for gendered nationalism was 28% lower than for working-class men. Among Republicans, by contrast, working-class men and women were not particularly distinctive in terms of their gendered nationalism beliefs. Support is high among Republican men regardless of their class identification and was highest among upper class men. Support was also high among Republican women, and significantly higher than their Democratic women counterparts for each class category. In these respects, support for H 2 is mixed in that the link between class and support for gendered nationalism depends on party and gender.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between gendered nationalism and educational attainment, also taking into account gender and party identification. Panel A shows agreement with the statement that the United States has grown too soft and feminine among men and women based on whether they have earned a 4-year college degree. Regardless of gender identification, a college degree corresponds to lower levels of gendered nationalism. There was an 18% difference among men based on their educational attainment, and a 22% difference among women. These results suggest that a college education had a similar effect on men and women, driving down levels of gendered nationalism, consistent with H 3.

Figure 2. Relationships between educational attainment and gendered nationalism. Data are the percentage of respondents who somewhat agreed or strongly agreed with the “too soft and feminine question.” Survey weights have been applied.

Differences based on party are included in panel B. Again, the differences across party are stark, with Republicans more likely to report gendered nationalism beliefs compared to Democrats regardless of education level and sex. For Democrats, support for gendered nationalism was quite low among those with a college education compared to those without a college degree. Educational differences among Republicans were notably more modest. Republican men without a college degree were more supportive of the idea that the United States has grown too soft and feminine by a 7% margin, but among Republican women, there was no difference in support for this idea among those with and without a college degree. Thus, we recognize qualified support for H 3, as in our findings regarding educational attainment, which depend to some extent on party and gender.

Taking into account the intersections between gender, class, and party, the relationships between voters’ various group memberships are complex and contingent. To more carefully examine these relationships, we estimated an ordered logit model predicting responses to the gendered nationalism question on the full four-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The model includes gender, class, party, and a host of other demographic control variables (see Table A1 in the Online Appendix for details). The results are presented in the first column of Table 1.

Table 1. Determinants of gendered nationalism beliefs

Entries are ordered logit coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. Survey weights have been applied. + p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Differences in endorsement of gendered nationalism based on gender, party, and class persist in a fully specified model. All else equal, women were significantly less likely than men to endorse the belief that the United States has grown too soft and feminine, consistent with H 1. The findings for class are somewhat more tempered in the multivariate analysis. Self-identified class is included as a series of dummy variables, with the middle-class serving as the baseline category. The upper- and lower-class respondents did not differ from middle-class respondents in their endorsement of gendered nationalism beliefs. However, people who identified as working class were significantly more likely to agree that the United States has grown too soft and feminine, though the effect was marginally significant (p = .09) in a two-tailed test. This finding supports the idea that working-class voters hold a distinctive set of beliefs about gender and responded to the gender dynamics in the campaign with heightened support for Donald Trump's candidacy, consistent with H 2.Footnote 4 In addition, our analysis reveals a negative and statistically significant relationship between earning a college degree and endorsement of gendered nationalism, consistent with H 3. This model includes controls for partisanship, and partisanship proves to be an important determinant of gendered nationalism as well. Party is a series of dummy variables and the coefficients for Independents and Republicans compare these groups to Democrats (the baseline category). Relative to Democrats, both Independents and Republicans were significantly more likely to endorse gendered nationalism beliefs. Notably, whether a respondent is an Evangelical Christian or whether he or she attends church regularly does not appear to have driven attitudes about gendered nationalism.

Given the role that partisanship played in moderating the effects of class and educational attainment in the analysis presented in Figures 1 and 2, we evaluated whether partisanship moderates the effect of these factors in the fully-controlled models presented in the second and third columns of Table 1. The model in the second column includes interactions between partisanship and class identifications. With these interactions in the model, the coefficients for the class dummy variables showed the effects of class among Democrats, relative to middle-class Democrats. Working-class Democrats were significantly more likely to agree that the United States has grown too soft and feminine, consistent with H 2. However, the same pattern did not emerge among Independents or Republicans. Although both Independents and Republicans were more likely to agree with the sentiment, support was not as variable across class. One exception occurred among upper-class Republicans, who scored higher than their counterparts on the gendered nationalism measure. Again, support for H 2 is mixed. Working-class identification did boost gendered nationalism, but only among Democratic Party identifiers.

The model in the third column includes interactions between partisanship and educational attainment. With the interactions between the party dummy variables and college dummy variable in the models, the coefficient for college is the effect of a college education among Democrats. It is negative and statistically significant, indicating that college-educated Democrats scored considerably lower on gendered nationalism. The nonsignificant coefficient on the interaction term for Independents suggests a similar effect among Independents. However, the coefficient on the interaction term for college-educated Republicans is statistically significant and positive, suggesting that the liberalizing effect of a college degree among Republicans was significantly smaller, and much closer to zero, than for Democrats. Based on this analysis, we conclude that gendered nationalism was less common among college-educated voters in 2016, but that the relationship between the two factors was conditional on party identification.

GENDERED NATIONALISM AND VOTE CHOICE

To assess the consequences of gendered nationalism for vote choice in 2016 (H 4) and to evaluate whether the gender gap in vote choice can be largely explained by gender differences in gendered nationalism (H 5), we estimate a series of logit models predicting whether or not a person voted for Donald Trump. We hypothesize a mediated relationship between gender and vote choice, namely that the effects of gender on vote choice are mediated by or funneled through gendered nationalism beliefs. We expect that when gendered nationalism is included in our vote choice model, the effect of voter gender would go to zero, because the effect of gender is indirect and is conveyed through gendered nationalism. Following the approach to evaluating mediation outlined by Baron and Kinney (Reference Baron and Kenny1986), we estimate our vote-choice model first without the hypothesized mediator (gendered nationalism) and then include the hypothesized mediator for comparison. The dependent variable is the two-party vote, coded one for a Trump vote and zero for a Clinton vote. The results are presented in the first and second columns of Table 2, respectively.

Table 2. The effect of gendered nationalism on vote choice in 2016

Entries are logit coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. Survey weights have been applied. + p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

In the first vote-choice model, which does not include the gendered nationalism variable, the coefficient for voter gender is statistically significant, indicating that women were much less likely than men to vote for Trump, all else equal. In the second vote-choice model, in which gendered nationalism is included as a predictor, the coefficient for gender is not statistically significant, suggesting no gender gap in support for Donald Trump. A post hoc Wald test comparing the size of the coefficients for respondent gender in models I and II suggests that the coefficient is significantly reduced by the inclusion of the mediator [F(1,678) = 10.19; p < .0015], consistent with a mediational process (Baron and Kinney Reference Baron and Kenny1986). Thus, in accordance with our mediation hypothesis (H 5), gender differences in beliefs that the United States has grown too soft and feminine largely account for the gender gap in support for Donald Trump in 2016. As we can see from the second model, gendered nationalism proves to be a significant predictor of voting for Donald Trump, consistent with H 4.Footnote 5

To illustrate how the gender gap is largely explained by gendered nationalism, we calculate the predicted probability of voting for Donald Trump among men and women in the two models described above. These predicted values, surrounded by 95% confidence intervals, are presented in Figure 3. On the left side of the figure is the gender difference in the model that does not include gendered nationalism. Men were significantly more likely to vote for Trump than women; the confidence intervals do not overlap. On the right-hand side of the figure, predicted values for men and women are derived from the model that included the gendered nationalism variable. Here again, men were slightly more likely to vote for Trump, but the difference between men and women is no longer statistically significant. The results show that gendered beliefs, rather than gender in and of itself, are at the heart of the gender gap in support for Donald Trump.

Figure 3. Comparison of gender differences in the mediated and unmediated vote choice models. Data are predicted probabilities of the likelihood of voting for Donald Trump for men and women surveyed, derived from models I and II in Table 2. Predicted values are calculated for men and women, holding all other covariates to their modal values. The probabilities are surrounded by 95% confidence intervals. The mediating variable is gendered nationalism beliefs.

As one would expect, party and ideology also influenced vote choice. Independents and Republicans were significantly more likely to vote for Trump than Democrats, and conservatism was also associated with a heightened likelihood of voting for Trump. But even when controlling for these factors, gendered nationalism emerged as a significant predictor of vote choice. Class differences proved relatively modest in the vote-choice models, with upper-class voters less likely to vote for Donald Trump relative to middle-class voters, but no evident differences among working-class voters.

The effect of college education on vote choice is different between the two models. In the initial model excluding gendered nationalism, college education is associated with a significant decline in the probability of voting for Donald Trump. However, when gendered nationalism is included in the model, the effect of college education is no longer statistically significant. A post hoc Wald test comparing the size of the coefficients between the two models suggests that the coefficient for college was significantly reduced by the inclusion of the mediator [F(1,678) = 7.25; p < .0072], consistent with a mediational process like the one we observed for voter gender. This result, coupled with the finding that the gender gap in vote choice stemmed from gendered nationalism beliefs, suggests that differences we commonly attribute to voter characteristics may have been more strongly linked to attitudes about whether the United States had become too soft and feminine.

CONCLUSIONS

Our analysis suggests that gendered nationalism is a relatively common belief that corresponded to support for Donald Trump's candidacy in 2016. This previously unexamined belief about gender and society helps to explain popular support for Trump and likely continues to shape reactions to his presidential rhetoric now that he is in office. Endorsement of gendered nationalism coincided with many of the campaign narratives tied to the intersections of gender, class, and educational attainment, suggesting that it underlies the behavior of several key voting blocs in the American electorate. In particular, the finding that working-class voters held distinctive views on gendered nationalism is compelling given that many accounts of voting behavior in 2016 emphasized support for Donald Trump among the (white) working class. Although past scholarship has argued that there is limited evidence of class consciousness among American voters, class consciousness did emerge as a dominant theme in the election and, thus, may have been more salient than in the past. Our results point to the need for further research investigating whether class-based appeals resonated particularly strongly with voters in 2016 and whether there is broader evidence of politicized working-class identities among voters to provide a more nuanced perspective on class and its implications for Americans’ political behavior.

Our results add to a growing body of literature that illustrates the important role that beliefs about gender played in the 2016 presidential contest (e.g., Junn Reference Junn2017). Although other studies have tended to emphasize factors like traditional gender roles, stereotypes, and hostile sexism (e.g., Bracic, Israel-Trummel, and Shortle Reference Bracic, Israel-Trummel and Shortle2018; Cassese and Barnes Reference Cassese and Barnes2018; Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2019; Schaffner, MacWilliams, and Nteta, Reference Schaffner, MacWilliams and Nteta2018; Valentino, Wayn and Oceno Reference Valentino, Wayne and Oceno2018), we find evidence that this related, but conceptually distinct belief about gender was also at play. Unfortunately, our dataset does not contain these other measures of beliefs about gender, so we are unable to determine how gendered nationalism relates to the broader constellation of gender attitudes. However, our results speak to the need for further research to explore the multidimensional and multilevel manifestations of gendered political thinking.

Donald Trump won the presidency with one of the largest gender gaps recorded in modern American presidential election history. Yet our mediation analysis shows that once we controlled for gendered beliefs, specifically support for the notion that America had become too soft and feminine, gender differences in vote choice were not significant. Instead, holding more nationalist views helped to shape voters’ decisions in 2016. Although our analysis supports the notion that Trump's overtly masculine, chauvinistic campaign style did appear to have an impact for many men, it likely held appeal for conservative women as well.

Our mediation analysis also shows that differences in vote choice between college-educated voters and those with less than a college degree were also linked to gendered nationalism. When gendered nationalism is included in our vote-choice model, the liberalizing effect of a college degree was eliminated. Previous research has demonstrated a relationship between educational attainment and other beliefs about gender, such as hostile sexism (e.g., Cassese and Barnes Reference Cassese and Barnes2018). This relationship between education, attitudes toward gender, and political behavior warrants further study, particularly in light of evidence that college-educated women were a distinctive voting bloc in the 2018 midterm elections (Tyson Reference Tyson2018). Of course, other factors may intersect with gender in ways that could be relevant for understanding gendered nationalism. Although our sample does not situate us to make robust comparisons across racial and ethnic groups,Footnote 6 prior research suggests that beliefs about gender can operate differently across voters based on their gender and race identifications (e.g., Frasure-Yorkley Reference Frasure-Yokley2018). Future research should more carefully interrogate these race–gender intersections.

We recognize the limitations of suggesting that mediating relationships explain gender differences with observational data and without probes of the hypothesized mediating process (Green, Ha, and Bullock, Reference Green, Ha and Bullock2010). Further research should more carefully evaluate the causal mechanism at work here using an experimental approach. For example, researchers might experimentally prime gendered nationalism by assigning participants to view video clips or newspapers stories where political candidates invoke themes related to gendered nationalism, and then evaluate the effects of the primes on candidate evaluations or policy attitudes. It seems plausible that gendered nationalism is bound up not only in preferences for male candidates who emphasize their masculine traits, as we find here, but also in policy preferences associated with strong nationalist postures in areas like immigration and national security.

The finding that attitudes about gendered nationalism have a bigger impact on vote for president in 2016 than biological sex is consistent with other research that finds, for example, that a voter's endorsement of hostile or benevolent sexism and their beliefs about gender-based inequality were more important factors in predicting whether someone voted for Trump rather than voter gender alone (Cassese and Barnes Reference Cassese and Barnes2018; Cassese and Holman 2018). Our findings join other scholarly work suggesting that gendered attitudes and personality traits have an independent and strong impact on different aspects of political behavior more broadly (McDermott Reference McDermott2016; Bittner and Goodyear-Grant Reference Bittner and Goodyear-Grant2017). Of course, whether the impact of attitudes concerning gendered nationalism is isolated to a unique presidential election in which the winner directly employed hypermasculine themes remains to be seen. Other scholars have noted that in previous political eras, a hypermasculine national mood pervaded American politics, such as during the McCarthy and Cold War periods (Storrs Reference Storrs2007), though we do not have the survey data necessary to evaluate its ties to political behavior. We suggest that more research is needed to examine whether gendered nationalistic attitudes are linked to voting behavior in other elections or to other aspects of political behavior more broadly. Finally, developing more thorough gendered nationalism measures is also warranted, as is consideration of how such attitudes are explicitly linked to attitudes about sexism.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X19000485.