Introduction

Here we report the first record of the Dorantes longtail, Thorybes dorantes = Urbanus dorantes (Stoll, 1790) (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae), in Canada. We found a single adult (Fig. 1) on 16 April 2023, along the northwest shore of Lake Ontario, resting and flying along the beach of Marie Curtis Park (43.58235, –79.54295), in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Figure 1. Dorantes longtail, Thorybes dorantes, found on a lakeside beach in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Photo credit: M. Johnson.

The individual was a fresh adult with little wear, and it exhibited active behaviour. The lack of wear suggests the individual likely emerged from its pupa shortly before being observed. We first spotted the individual resting on the sand of a beach near the water’s edge, and shortly thereafter, it flew a short distance when approached. While we were photographing it, it flew a longer distance, heading west across the beach parallel to the water, and it was not seen again.

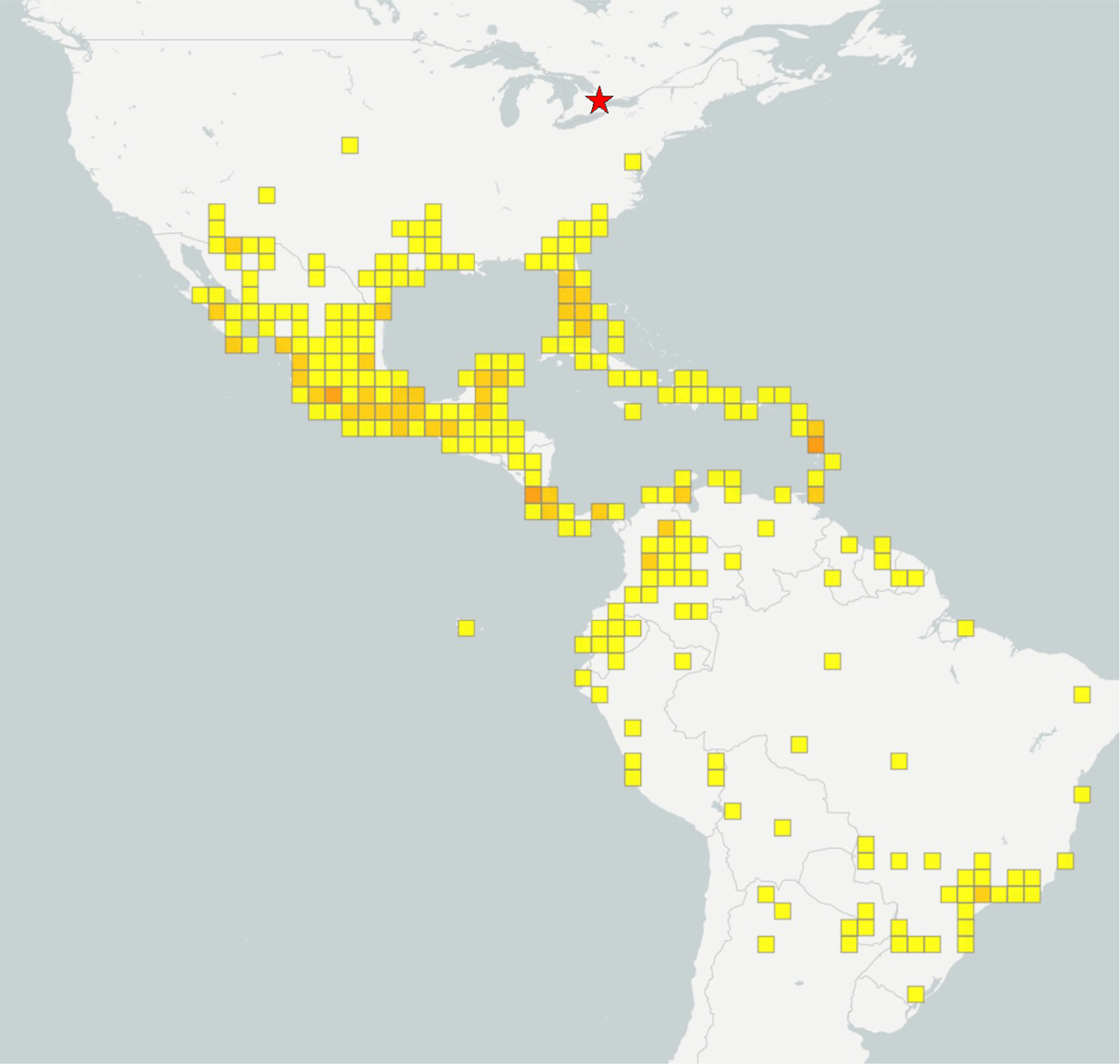

Our observation occurred far outside of the normal range of the Dorantes longtail. The species has a broad distribution in tropical and hot temperate climates, from northern Argentina and southern Brazil through Central America, the Caribbean islands, and the southern United States of America, primarily within southern Arizona, southern Texas, and Florida (Fig. 2). Before our observation, the most northerly sightings were recorded from Maryland and Missouri (Global Biodiversity Information Facility Secretariat 2024; Lotts et al. Reference Lotts and Naberhaus2024). Both the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (https://www.gbif.org) and iNaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?taxon_id=1245921) databases list occasional vagaries closer to the northern edge of the species’ North American range, including reports from Arkansas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Oklahoma, United States of America. Most vagaries are reported in September but occasionally also in July. The observation of the Dorantes longtail in April from Toronto is approximately 1500 km from the northern Florida population and 2000 km from the easternmost population in Texas. In short, our observation reported here is without precedent for this species.

Figure 2. Global distribution of Dorantes longtail, Thorybes dorantes. Darker squares indicate more observations in that region. Location of new Canadian record shown as red star. Map adapted from gbif.org.

The Dorantes longtail is a fairly large tropical to subtropical skipper (Lotts et al. Reference Lotts and Naberhaus2024). It typically has 3–4 generations per year, feeding on various wild (e.g., Desmodium spp.), cultivated (e.g., Phaseolus), and horticultural (e.g., Clitoria) legumes (Fabaceae). As an adult, the butterfly feeds on nectar from a variety of plants, including Lantana (Verbenaceae), Trilisa (Asteraceae), Vernonia (Asteraceae), and Bougainvillea (Nyctaginaceae), among others. Adult abundance peaks between August and November and is least abundant from February to June. The species is typically found in open fields and roadsides.

The obvious question that arises is, how did this individual come to be in Canada, given that it represents a major disjunction from its core range and all previous reports of vagaries? We propose six possible scenarios of how the observed individual came to Toronto: (1) it was brought in on produce; (2) it came in through the horticultural trade; (3) it escaped from a local indoor tropical butterfly conservatory; (4) it escaped from the private trade in butterflies or from a butterfly collector; (5) it flew up from southern populations during a preceding unusual warm period with strong southerly winds; or (6) it is a member of a nearby undiscovered resident population. We discuss each of these scenarios and their likelihoods below.

We believe scenario 1 is most likely – that the observed individual was accidentally brought to Toronto on produce. In this scenario, larvae or pupae were transported to Canada, possibly on their food plant, and emerged from their pupae, and we found the individual soon after its emergence during unseasonably warm weather. This scenario seems especially likely given that the Ontario Food Terminal (Etobicoke, Ontario, Canada; https://www.oftb.com) is just 6.75 km NE of the location where we found the individual. The terminal is the largest wholesale fruit and vegetable distributor in Canada, distributing more than 2.5 million kilograms of produce daily. Growers from all over the world ship to the terminal. Given the prominent role of hubs of distribution for invasive species (Morel-Journel et al. Reference Morel-Journel, Assa, Mailleret and Vercken2019), it is highly likely that many insects are introduced to the Toronto area via this route, and it is plausible the individual we observed came in on its food plants as either a larva or pupa, emerged from its pupa, flew to the lake, and followed the shoreline to the point where we observed it. The freshness of scales, which showed almost no wear, supports a recent emergence and little active flying before our observation.

It is possible but unlikely that the individual came in via the horticultural trade (scenario 2) or escaped from the commercial butterfly trade (scenarios 3 and 4). Relatively few horticultural Fabaceae (ornamental or vegetable garden species) are actively grown in April because most horticultural planting in Ontario begins in mid- to late-May. Moreover, most sources of these materials are local, as opposed to being imported. Two butterfly conservatories are located within 70 km of Toronto; however, these living collections do not import or rear T. dorantes because it is small butterfly, exhibits fast erratic flight, and is not brightly coloured – features that make it less desirable for public exhibitions of living collections (Adrienne Brewster, Cambridge Butterfly Conservatory, Cambridge, Ontario, personal communication; Sean Dunn, Niagara Parks, Niagara Falls, Ontario, personal communication). Similarly, it is unlikely that the observed individual had escaped from the lawful commercial insect trade because the status and importation of T. dorantes is regulated by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (Ottawa, Ontario) under the Plant Protection Act (https://inspection.canada.ca/en), the species is not listed as a species traded by major suppliers of tropical butterflies (e.g., https://www.butterflyfarm.co.cr/our-species; https://www.elbosquenuevo.org; https://www.butterflydans.com/species-list), and it is not highly sought after as an exhibit species due to its small size, lack of bright colours, and cryptic appearance (Corrianne Brons, Butterfly Wings ’n’ Wishes Laboratories, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, personal communication).

An intriguing possibility is that the Dorantes longtail individual migrated to Canada as a long-distance vagary (scenario 5). The week we observed the individual was unusually warm, with daily highs ranging from 29 °C on 13 April to 24 °C on 16 April, when we observed the butterfly in Toronto. The daily low temperatures were similarly warm, ranging from 12 to 14 °C. The winds were also from the south throughout this period, and maximum wind speeds ranged between 17 km/hour and 39 km/hour. This heatwave with southerly winds was widespread along possible routes of migration from both Texas and Florida, with temperatures at or above 23 °C starting around 13 April for cities south of Toronto in the United States of America, including Memphis, Tennessee, Indianapolis, Ohio, Charlotte, North Carolina, Roanoke, Virginia, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Detroit, Michigan (https://www.wunderground.com/history). Winds were typically from the south or southwest for most of these cities during this time. Despite the weather aligning with a possible northwards migrant-butterfly trajectory on brisk warm winds, we still see scenario 5 as less likely than a local introduction via the Ontario Food Terminal. Such a long flight would likely cause considerable loss of scales and wing damage, which is inconsistent with the freshness of the individual we observed. Moreover, Dorantes longtail adults are most active in August–September in North America, with March, April, and May being months with the lowest abundance. Therefore, although the observed individual could be a long, northwards vagrant migrant, we see this scenario as being much less likely than scenario 1.

The last and least likely explanation posits the existence of undetected nearby populations of Dorantes longtail (scenario 6). The Dorantes longtail has extended its range in the past six decades. For example, the species is thought to have been absent from Florida before 1970 (Clench Reference Clench1970; Knudson Reference Knudson1974) but has since extended its range throughout much of Florida, with multiple additional records in southern Georgia. However, no known self-sustaining populations are known between Georgia and Canada, and it is highly unlikely that a population has remained undetected, given the popularity of amateur butterfly observations and the distinctive appearance of this species. For example, more than 41 300 observations of butterflies were reported in 2023 in Ontario alone, with the highest density of observations occurring around Toronto. The Dorantes longtail’s largely tropical–subtropical distribution also makes a north-temperate population expansion implausible. For these reasons, we see scenario 6 as less likely than the other scenarios noted.

Human-assisted introductions explain other new and unusual records of butterflies in Canada, some of which have led to established populations. For example, Aglais io, the European peacock butterfly (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), was first discovered in Montréal, Quebec, in 1997 and is now well established there (Nazari et al. Reference Nazari, Handfield and Handfield2018), with isolated occurrences outside of Quebec (https://www.gbif.org/species/4535827). Similarly, Polyommatus icarus, the common blue butterfly (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae), was observed in Montréal, Quebec, in 2005 (Hall Reference Hall2007) and is now common in Montréal, Toronto, Belleville (Ontario), and northern Vermont, United States of America, and has been found in other scattered locations in North America (https://www.gbif.org/species/1933268). Pieris rapae, the cabbage white (Lepidoptera: Pieridae), and Thymelicus lineola, the Essex or European skipper (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae), were accidentally introduced in Canada around 1860 (Scudder Reference Scudder1887) and 1910 (Hall Reference Hall2007), respectively, and have become some of North America’s most common butterfly species. However, other introductions result in no established populations, such as the single Papilio memnon (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae) male that was reported in Toronto in 2017 (https://inaturalist.ca/observations/13501251); this observation is particularly remarkable because this species is native to tropical Asia and Oceania. All of these are examples of human-assisted introductions, although the exact means by which the species came here may vary on a case-by-case basis.

In conclusion, our observation of Dorantes longtail in Toronto represents the species’ first record in Canada. The individual likely arrived on produce via the nearby Ontario Food Terminal. Although the Dorantes longtail is unlikely to establish a population in Canada, its observation here is a significant example of the constant pressure and threat of introduced species to the region and of the importance of hubs for introduced species (Morel-Journel et al. Reference Morel-Journel, Assa, Mailleret and Vercken2019). Although most introduced insects perish soon after being introduced into new territories, some establish populations and become invasive.

Acknowledgements

We thank Peter DeGennaro for assistance with the initial identification of our observation. Some of the ideas for explaining how the observed Dorantes longtail individual came to Toronto were stimulated by an online conversation with P. DeGennaro, Rick Cavasin, and Colin Jones as part of our original iNaturalist observation (https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/155196976). We also thank Laura Timms for editing the paper and two anonymous reviewers who helped expand our thinking on the possible origins of Dorantes longtail in Canada. This work was supported by an NSERC Discovery Grant to M.T.J. Johnson.