Mystery, myth and legend has long obscured historical research on the Knights Templar, although recent studies have started to highlight the effectiveness of these warrior monks as rural landowners in England. Despite a growing literature on the role of monastic and religious orders in the development of medieval towns, relatively little attention has yet been paid to the Templars’ role in English towns. This article explores how the Order developed new urban settlements and markets, acquired property within existing towns and established residences and chapels for its brethren there. The Knights Templar existed in England for less than two centuries, from the visit of the Order's first grand master, Hugh de Payns, to England in 1128 to the suppression of the Order by the papacy in 1312, following the arrests of its brethren and their subsequent trial. Yet over this short period, the Knights Templar had a profound and lasting impact on several English towns.

As the diversity of religious provision in England increased during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the roles that religious houses played in towns became more varied, as they acted as landlords and consumers, providers of spiritual services and urban infrastructure. Many religious houses were urban landlords, even if they were not sited in a town themselves. These included the Benedictines, various orders of regular canons (clerics living in common and following a monastic rule) and even the Cistercians. While the last-mentioned order initially placed prohibitions on the establishment of urban communities or the maintenance of urban property, by 1134 the Cistercians conceded that their abbeys might acquire property within towns, and most eventually came to possess some. These monastic urban holdings fulfilled at least three functions: as a lodging place for brethren free from secular temptations; as a profitable source of rental income; and as a base for commercial and administrative activity, a sort of urban grange. The types of property varied reflecting the different functions of the urban holdings, and included hostels, shops and warehouses.Footnote 1 Larger and wealthier religious houses, particularly the Benedictine cathedral priories, were important urban consumers of foodstuffs, fuel, building materials and higher value goods, and employers of servants and building workers.Footnote 2 Some houses employed freelance scribes and established schools, stimulating wider education and literacy.Footnote 3 They might also provide infrastructure that benefited other urban residents as well as their own community, such as the water conduits constructed by friaries and other religious houses.Footnote 4 While the wider role of religious houses in medieval towns arguably still lacks the attention it deserves in relation to its importance within medieval English society, the particular role of the Order of the Knights Templar has been seriously understudied in relation to its impact.

The Knights of the Temple of Solomon of Jerusalem were established c. 1120 after the First Crusade to protect pilgrims journeying to Jerusalem. These knights, who were professed members of a religious order, soon became involved in defending the Crusader States, and later in the expansion of Christendom in the Iberian peninsula and central and eastern Europe. The Templars held extensive estates across western Europe that produced revenue and resources for their knights in the Holy Land. In addition to their possessions in cities in the Crusader States, the Templars had houses in key urban locations across western Europe, including most of the important Atlantic and Channel coast ports and in the Italian cities of Siena, Luca, Pisa, Florence and Venice.Footnote 5 A recent survey of the Order in northern Italy, the Iberian peninsula and southern France has found them to be heavily involved in urban society, shaping the material and physical features of cities as well as social, economic and legal practices.Footnote 6

Assessing the urban role of the Templars in England is made more difficult by the lack of sources relating to the Order. Surviving architectural and archaeological evidence is mostly to be found within a rural context, although there have been recent studies of the English headquarters of the Templars and Hospitallers in London.Footnote 7 Many of the administrative records generated by the Templars themselves, including their court records and accounts, have been lost, but one important survival is the Inquest of Lands made in 1185 at the request of Geoffrey FitzStephen, master of the Temple in England. Collected from sworn jurors and collated centrally, it records the donors of land, tenants and the rents and services owed.Footnote 8 The subsequent development of the Order's property holdings, notably royal grants of markets and fairs, can be traced in references in the Charter, Close and Patent Rolls of royal government as well as in urban rentals. Following the arrest of the brothers in 1308, the crown made inventories of the goods found in local houses and maintained detailed accounts of the produce and expenses of the estates, while evidence given at the Templars’ trial provides further details about the Order.Footnote 9

Historians have drawn on this evidence to demonstrate the influential role that the Knights Templar played as rural landowners in England.Footnote 10 They have calculated that the Templars owned over 300,000 sheep in 1308, producing about 39,000 lbs of wool a year, around 50 per cent of their entire income for England and Wales.Footnote 11 In Lincolnshire, the Templars were embracing the best of early fourteenth-century agricultural practice, including extensive use of manuring, multiple ploughing, weeding, leguminous crops, manipulation of the sowing rate and effective animal husbandry.Footnote 12 Recent studies have shown how the Templars’ estate centres, known as preceptories, formed the focal points for their agricultural holdings.Footnote 13 Far less attention has been paid to the Order's urban activities, although the only study to do so for the British Isles has noted their impact on urban life through their possessions, privileges, tenants and by offering some spiritual services, as well as their attempts to create new urban settlements.Footnote 14 Building on that initial survey, this article examines and evaluates the impact that the Order made in establishing new towns and through holding urban property and privileges, which were integral to the wider exploitation of their rural resources.

Town and market promoters

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, many monasteries and bishops founded new towns on their lordships, with such foundations peaking in the period 1180–1220. Benedictine monasteries created settlements at the gates of their abbeys, including early developments at St Albans, Bury St Edmunds, Peterborough and Ely, and speculative developments in the suburbs of existing urban centres, as at Bath, Durham and Worcester. They also laid out new urban developments on rural estates, particularly during the thirteenth century, like Ramsey Abbey's development of the river port of St Ives, and Worcester Priory's development of Shipston on Stour.Footnote 15 Although the Cistercian order did not generally settle in towns or encourage towns to develop immediately outside their precincts, they founded the particularly successful town of Wyke, subsequently acquired by the crown and known as Kingston upon Hull, as well as a handful of smaller settlements, including Kingsbridge (Devon) and Wavermouth (Cumberland).Footnote 16 Other religious houses capitalized on the growing importance of existing towns to convert part of their agricultural holdings to planned settlements, like the Cambridge priory of Augustinian canons at Barnwell and Chesterton.Footnote 17

The Templars’ efforts as town and market promoters in England, though, have not been seen as successful or significant. Urban historians have claimed that Baldock was the ‘only urban venture of the Templars in England’, or that they founded only a few new towns in England, several of which turned out to be unsuccessful ventures.Footnote 18 A closer analysis of the Templars’ urban foundations, though, reveals a different picture of modest success, as the example of Bristol illustrates. The Knights Templar joined the earls of Gloucester and the lords of Berkeley in creating a planned settlement that began with a grant from Robert earl of Gloucester of the eastern part of the area over the Avon, which became known as the Temple Fee. A degree of co-operation between the Templars and aristocratic investors in Bristol's infrastructure is shown by the construction of the Law Ditch, the boundary between land developed by the Order and the Fitzharding family, lords of Berkeley, who held the adjacent suburb of Redcliffe. This ditch was planned and dug to serve as a drain for the tenements on both sides. Three streets also connected the Templars’ suburb to Fitzharding's St Thomas Street.Footnote 19 In 1240, a writ instructed the men of Redcliffe and tenants of the Templars to construct a wall to the south of the suburb, using proceeds of tolls taken at gates. The Temple Fee quickly became a thriving urban area, with its own market; a borough was noted in 1306, and craftworkers including weavers established themselves there.Footnote 20 Creating an urban plantation alongside another urban settlement in an attempt to benefit from the convergence of economic activity occurred elsewhere, notably in Devon, where the Cistercian abbey of Buckfast founded Kingsbridge alongside Dodbrooke, and the Premonstratensian canons of Torre Abbey developed Newton Abbot alongside the rival borough of Newton Bushel, but unlike these examples, the Temple Fee complemented rather than competed with its larger neighbour.Footnote 21

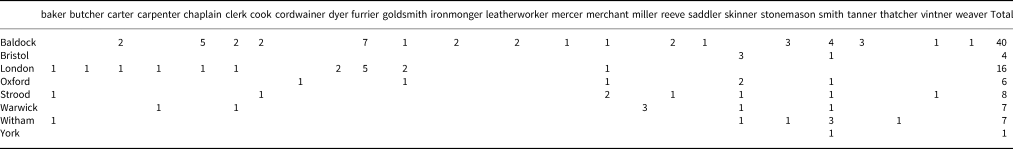

Baldock was another successful urban settlement established by the Templars, and one of a cluster of towns, along with Chelmsford, Braintree, Brentwood, Epping, Chipping Barnet and Royston, that were developed in the late twelfth century, mainly by ecclesiastical landlords, on roads leading north-eastwards from London.Footnote 22 Drawing on Baldock's location at the intersection of a main route from London and the Icknield Way, the Templars appear to have rearranged the roads to form a cross shape with two widened arms along the High Street and Whitehorse Street (formerly Broad Street) to create elongated triangular market places. The parish church overlooks the point where they meet. Burgage plots were laid out along the streets, with back lanes providing rear access. This cross plan may have been a deliberate use of Christian iconography but it could merely have been a practical consequence of diverting roads into the town.Footnote 23 The Templars may also have constructed a new church here. The church is dedicated to St Mary, a popular Templar dedication, although it was mostly rebuilt in the fourteenth century.Footnote 24 While some have suggested that the place-name is a corruption of the French word for the great Oriental city of Baghdad, known as ‘Baldac’ in western Europe, a derivation from Bald-oak or dead oak, seems more likely.Footnote 25 Baldock may not have been an entirely new settlement, as the size and wealth of the Domesday manor of Weston, with the large number of 75 households including two priests, suggests there was a late Saxon settlement, possibly already serving some urban function. Gilbert de Clare, earl of Pembroke (d. 1148) granted land to the Order from his manor of Weston, and by 1185 Baldock was a flourishing borough with 117 tenants holding 1½ acre plots, including a range of craftworkers and traders (Table 1). Rents from market stalls and shops totalled more than £6. The borough had been established with a licensed market during Henry II's reign, sometime before 1185, and this grant was confirmed in 1189 and 1199. As settlers came from Cambridge, Essex and London, it has been suggested that the Templars may have moved their tenants to new towns as well as attracting settlers by offering low rents and no labour services.Footnote 26 When the earl of Pembroke ratified the grant of his predecessors in the early thirteenth century, he noted how the Templars had ‘constructed a certain borough which is called Baldock and greatly improved the property beyond its value when acquired’.Footnote 27

Table 1. Occupational names recorded in the 1185 Inquest on the Templars’ urban estates

Source: Records.

Another urban settlement which grew from a village under Templar lordship was Witham (Essex). Acquired by the Order in 1147, the village was the site of a burh of Edward the Elder and may have been a centre of local trade before the Norman Conquest. The market, for which the Templars acquired confirmations in 1153, 1189 and 1199, was held by the parish church, at Chipping Hill, and in 1185 the market, comprising the tolls, and rents of stalls and shops, was farmed out for 60s.Footnote 28 More than a third of the tenants listed held fewer than 8 acres, suggesting that they did not rely solely on their own land for their living.Footnote 29 Around the beginning of the thirteenth century, the Templars decided to found a new town around half a mile from the market at Chipping Hill. A charter was obtained in 1212 for a market and fair ‘at our new vill of Wuluesford in the parish of Witham’, which became known as Newland. Around 44½ acres were set aside for building plots for the new town at a standard annual rent of 2s an acre. The total annual income from Newland, including the market, court dues and tolls, was between £8 and £9 at the end of the thirteenth century. This was probably only £7 a year more than the income that would have been received as agricultural land.Footnote 30

The acquisition of market privileges by the Templars at Wetherby in Yorkshire, as at Witham, seems to have been the catalyst for urban development. Just two years after receiving two large grants of land in Wetherby in 1238, the Order obtained a royal grant to transfer to Wetherby the Tuesday market and yearly fair on the Nativity of St John the Baptist that they had received in 1227 to hold at nearby Walshford, 4 miles further north. As well as moving location, the grant of 1240 changed the market day to a Thursday and the fair to the feast of St James the Apostle. In 1242, a neighbouring lord, Margery de Rivers, agreed that the knights could hold their market without hindrance from herself or her heirs, having previously claimed it had been to the injury of her manor of Harewood, 5 miles to the west of Wetherby.Footnote 31 By 1308, this small town was a profitable trading centre, with the Templars drawing income from the stallage of the marketplace, leased for 30s, fees and perquisites of the manorial court worth £2, two water mills valued at 10 marks and a salmon fishery.Footnote 32

Other markets established by the Templars, however, despite their proximity to preceptories, never developed into urban settlements like Witham or Wetherby. At South Cave (Yorks., E.R.), 2 miles from their preceptory at Weedley, the Templars were assigned the market and fair by Roger de Eyville in 1253 that Roger de Mowbray had held between c. 1170 and 1184. The Templars were operating this market a generation later when they were alleged to take excessive tolls during the Quo Warranto enquiries of 1279–81. The Templars obtained another grant at South Cave in 1291 of a Monday market and five-day fair around Trinity Sunday, although whether this created an additional market and fair, or merely formalized the Templars’ rights to the existing prescriptive market and fair, is unclear. A new settlement seems to have developed at South Cave around the marketplace, on the main road from Brough to York, about half a mile from the older part of the village around the church at West End. The market and fair continued to be held in the early modern period, suggesting that it was a relatively successful foundation.Footnote 33 Around their preceptory at Temple Balsall (Warw.), the Templars were granted in 1268 a Thursday market and two fairs, on the vigil, feast and morrow of St George the Martyr, and the vigil, feast and morrow of St Matthew.Footnote 34 There were also attempts to create a borough, providing freehold tenures without the obligations required by villain tenure. Evidence for burgage tenure survives in a survey of 1538–39 and a rental of 1648. Given the Templars’ efforts elsewhere, it seems likely that they were the original promoters of the borough at Temple Balsall, although there is no evidence to suggest that the markets and fairs were ever held.Footnote 35

Temple Bruer (Lincs.) was the site of another preceptory where the Templars were granted a market that failed to develop. In 1259, as the Thursday market granted during Henry II's reign had ‘hitherto not been made use of’, a change of market day to Wednesday was made, and at the same time, a three-day fair on the feast of St James the Apostle was granted.Footnote 36 In a relatively remote location, midway between roads from Lincoln to Stamford and to Sleaford, the Templars’ market and settlement does not seem to have been successful, and there is now only a single isolated farm, although the settlement established by the Templars is shown by soil marks to the south-east of the preceptory.Footnote 37 The Knights Hospitaller's abortive town plantation at New Eagle (Lincs.) lay in a similarly isolated location on the Foss Way between Lincoln and Newark, and failed to develop despite the grant of a market and two fairs in 1345 and the proximity of a Hospitaller commandery.Footnote 38 Despite their road links, both Temple Bruer and Eagle were in isolated locations, and the respective preceptories were too small to generate significant demand to sustain these urban foundations.

Another unsuccessful Templar market alongside a preceptory was at Rothley (Leics.). The Templars obtained a grant of a Monday market and fair on the feast of St Barnabas at Rothley in 1284, but in 1306 Edward I granted them a Wednesday market and fair on the feast of St Mary Magdalene in lieu, to be held at their manor of Gaddesby, where they had a grange. This market was not recorded in the sheriff's accounts of 1308, suggesting that it failed or never materialized.Footnote 39 There is a triangular marketplace at Cross Green, but the thirteenth-century custumal of the soke of Rothley includes only the occupational surnames of carpenters, millers, a forester and cleric in Rothley and Gaddesby.Footnote 40 The reason behind the change of location for the market is unclear. Perhaps Rothley, lying between the larger markets of Leicester and Loughborough, struggled to attract trade, or the Templars’ difficulties with their soke tenants there did not support the market, while the establishment of a market and fair at the neighbouring settlement of Mountsorrel in 1292 may also have created competition.Footnote 41

While the acquisition of market charters was not necessarily an indicator of urban development, as several of the examples above have shown, the extent of urbanization in the Templars’ foundations can be assessed by the occupational diversity of their residents. Small towns in medieval England usually had between 20 and 40 separate occupations.Footnote 42 The Templars’ survey of 1185 is an early date to make such a judgment, but Baldock already had 17 different occupations recorded including a goldsmith, mercer and merchant (Table 1). At Witham, there were several craft names among the tenants, including smiths, a baker, skinner and thatcher (Table 1). A further two tenants had an interest in the salt trade.Footnote 43 A survey of c. 1258 lists a variety of craftworkers in Witham including two chapmen, packman, porter, carpenter, miller, mason, potter, dyer and fuller. Around 1262, there may even have been an educational institution, as reference is made to ‘land of the Scolhus’.Footnote 44

Another measure of the success of these new towns is their wealth assessed in the 1334 lay subsidy. Temple Fee was not separately assessed, but included in the assessment for Bristol, which was the second wealthiest town in England. Baldock paid a subsidy of £132 in 1334, only £1 less than the 100th wealthiest town in the country, while Witham was assessed at £118, Gaddersby at £83, South Cave at £71, Temple Balsall at £60, Rothley at £46, Temple Bruer at £32 and Wetherby at only £14.Footnote 45 Beresford's survey of planted towns across England found that the average assessment was just over £44 and one third were assessed at less than £30, so on this basis, the Templars’ urban foundations, with the exception of Temple Bruer and Wetherby, were at least moderately successful. As with town plantations more generally, the oldest establishments, at Baldock and Witham, were the most successful.Footnote 46 The success of the Templars’ urban creations at Witham, Baldock and Wetherby is also demonstrated by the fact that all three settlements were sufficiently significant to be marked on the Gough map of the late fourteenth century.Footnote 47

The Templars’ more successful new town foundations shared similar characteristics. Each were within easy travelling distance of a preceptory: Witham lies 3 miles south-east of Cressing Temple; Baldock is 6½ miles north-east from Temple Dinsley; and Wetherby had both its own preceptory and another 5 miles south at Ribston. Each possessed a market, and the Templars were undoubtedly looking at opportunities to sell their own produce, particularly corn. Britnell has noted ‘the close association between the expansion of their demesnes during the thirteenth century and the creation and growth of local commercial communities’.Footnote 48 In 1185, the Templar tenants at Cowley (Oxon.) had carrying services to take corn to market, and at Temple Ewell (Kent), services included carrying grain to market, returning with salt, wheels and yokes from Canterbury.Footnote 49 Although these local markets probably handled few exports of wool, they offered the opportunity to purchase wool to supplement the stocks of the houses. The Templars’ markets and fairs also created an outlet for other local trade, increasing their income from tolls, stalls and court dues. More significantly, the most successful urban markets were at key crossing points of major roads and rivers or at the intersection of roads. Baldock was sited at the intersection of a route to London and Icknield Way, Witham where London Road crossed the River Brain and Wetherby where the Great North Road traversed the River Wharfe. Other religious orders chose to establish towns in geographically advantageous locations, such as St Ives, founded by Ramsey Abbey at the site of a new bridge.Footnote 50 The Templars did not, however, mirror the practice frequently found in towns planned by Benedictine monasteries, to locate marketplaces at monastic precinct gates.Footnote 51 This reflected the smaller size and less prestigious nature of Templar preceptories.

Templar residences: urban preceptories and camerae

Unlike many monastic orders, the Templars did not have large urban monasteries that provided major centres of consumption. The English houses of the Military Orders were more like the manorial complexes of minor lords than major monastic centres. The Templars’ estates were administered from preceptories, overseen by knights of the Order known as preceptors, and rarely housed more than a few brothers. They collected produce and revenues, provided bases at which members might be recruited and received into the Order and acted as spiritual centres where brothers said the daily offices and chaplains commemorated the souls of benefactors. Although only one English preceptory has been excavated completely, at South Witham in Lincolnshire, documentary, architectural and archaeological evidence from a range of sites has shown that most rural preceptories had the same core features: a hall, chapel, agricultural buildings, bakehouses, brewhouses, dairies and forges. Precincts could be enclosed by a wall, and occasionally there were towers or gatehouses.Footnote 52 A camera (literally a room or chamber) referred to a manor or estate that provided funds for the support of the Temple.

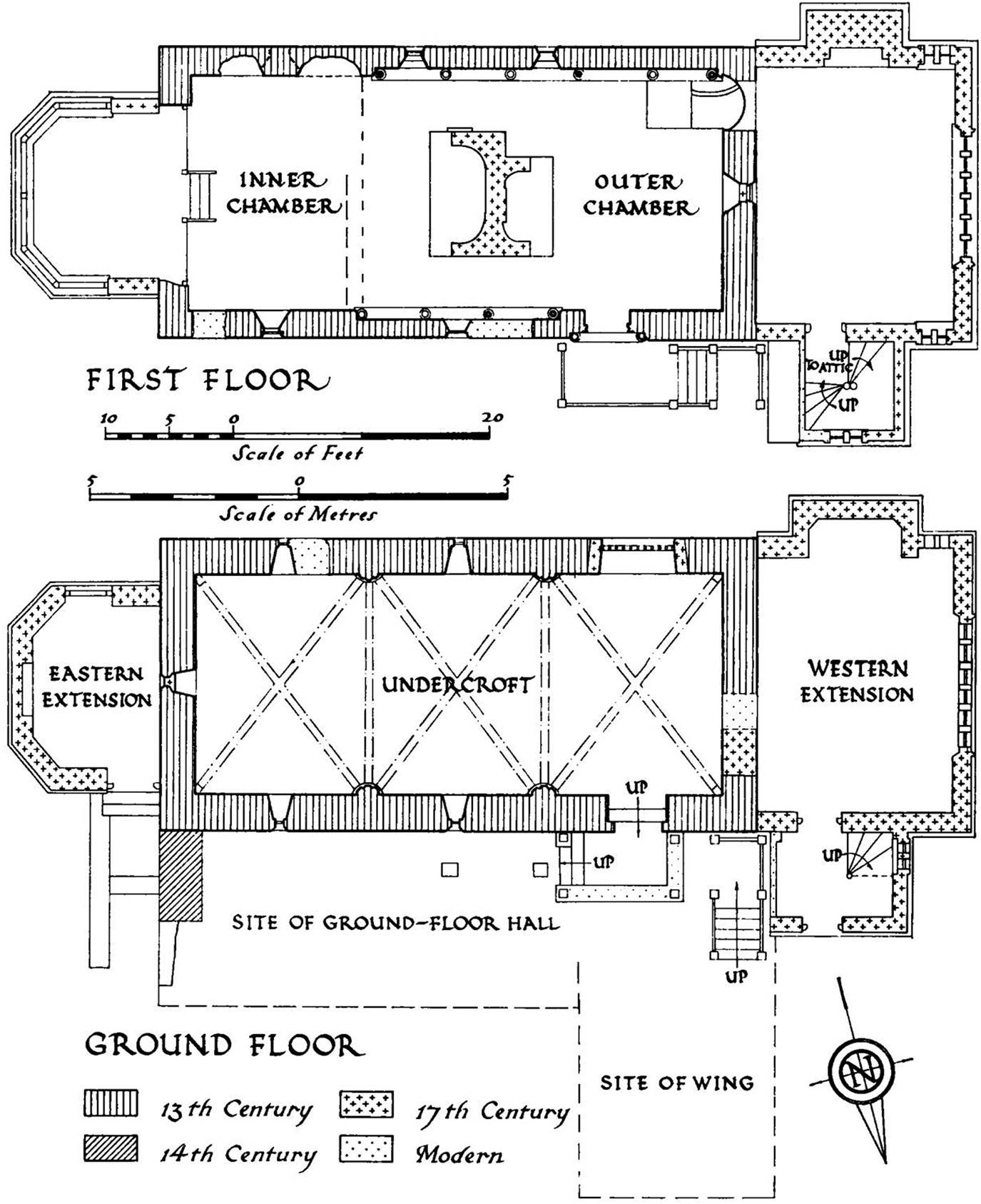

The Templars’ urban houses in England are even less well understood. They tended to be located in the more sparsely populated, semi-agricultural suburbs of towns. These included the London headquarters outside the city; at Dover, on an isolated position on the cliffs between the town and port; at York, outside the city walls beyond the castle; and at Warwick at Bridge End, on the south side of the Avon from the town centre. Physically, little now remains apart from the chapel for their head house, the Temple Church in London, together with the ruins of the Temple Church in Bristol and a surviving Templar camera at Strood in Kent. The camera is an early thirteenth-century building of ragstone and flint rubble with a first-floor hall divided into a high-status room to the west with a wall arcade on either side and a plainer room to the east, and an undercroft below with three bays of ribbed vaults (Figure 1). This camera may have been built for one of Henry III's Templar almoners who travelled the Dover road between 1228 and 1245.Footnote 53

Figure 1. Plan of Temple Manor, Strood. Reproduced from S. Rigold, ‘Two camerae of the military orders’, Archaeological Journal, 122 (1965), 90. © Royal Archaeological Institute, reprinted by permission of Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group, www.tandfonline.com on behalf of Royal Archaeological Institute.

The administrative role of the Templars’ urban bases in managing their surrounding rural estates generally declined over the two centuries in which the Order operated. In 1185, Bristol preceptory was the administrative centre of the Order's lands in Gloucestershire, Dorset, Somerset, Devon and Cornwall, but the lands were later divided between the preceptories of Temple Guiting (Glos.) and Templecombe (Som.). Warwick, founded by Roger, earl of Warwick (d. 1153), was one of the earliest Templar houses in the country, but Temple Balsall, where there was a house in 1185, developed into the more important base within the county, becoming a preceptory by around 1220.Footnote 54 By 1292, the Templar mills at York were being managed by the preceptor of Copmanthorpe, a few miles to the south-west. There were no Templars arrested from either house in 1308, or from Wetherby, although an account given at the trial suggests there had been brothers resident at the latter site 20 years before.Footnote 55 Several rural houses, though, also appear to have been controlled from other preceptories by 1308, as the Order probably tried to rationalize its administrative overheads.Footnote 56

While their wider estate management functions may have declined, the Templars’ urban houses continued to provide important services for the Order and the wider community, which was reflected in an enduring physical presence within these towns. Like many other religious orders, the Templars’ urban houses provided hospitality. Holders of corrodies received board and lodging, or other support, in return for previous service or making a substantial donation. William Dokesworth, for example, was granted a corrody providing board, lodging and 20s a year for life at the New Temple in 1292, for his good service and care of the Templars’ mills at Southwark.Footnote 57 This hospitality may also have extended to pilgrims and travellers, like several of the Templars’ rural houses on important communication routes appear to have offered.Footnote 58 As an Order whose raison d'être had been to protect pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem, their properties in England may have provided a similar function.

Monastic houses provided places of deposit for precious objects and documents, and could be asked to provide loans and mortgage pledges for pilgrimage and crusade. The Templars, with their network of houses across Europe, including their complexes at Paris and London, developed a range of banking and financial services.Footnote 59 The New Temple in London provided a place of safe deposit, issued and paid out on bills of exchange, loaned money to the king and nobles, and paid debts on their behalf, and by the 1270s housed legal and government records.Footnote 60 The Templars’ urban bases elsewhere did not, in the main, provide these functions, although Robert de Seffeld, parson of Brampton, had deposited over £111 with the Templars at Dunwich (Suff.) for safekeeping in 1308.Footnote 61

Several Templar chapels in English towns, like many within urban communities on the continent, appear to have been used by the Order as opportunities to engage with the wider public and create parishioners.Footnote 62 At the Templars’ trial, Brother Michael de Baskerville, former preceptor of the New Temple in London, said that any of the people could come to the early morning mass. Other witnesses spoke of servants of Templars and others entering preceptory chapels.Footnote 63 At Bristol, the town weavers’ company used a chapel attached to the Templars’ church from 1299, and by 1308 the church had a vicar, indicating that the area around the preceptory had become a parish.Footnote 64 Some urban chapels housed relics, like Dunwich, where in 1308 there was one small chest with saints’ relics and another small chest with other relics.Footnote 65 Templar chapels also commemorated deceased donors, ranging from the priests who celebrated mass in the church of the New Temple for the soul of King John, to the chaplain there endowed by Idonia de Veteri Ponte after the death of her husband in 1228.Footnote 66 At York, William de Appleby paid 48s yearly for the support of a chantry.Footnote 67 The Templars could experience resentment from other religious organizations when they provided these spiritual services in towns, as occurred in Shoreham. The abbot of Florent in Samur, who had been granted the parish church of Old Shoreham, complained that the Templars’ oratory, established by c. 1170, was contrary to his privilege. But as Pope Alexander III had granted the Templars licence to build the chapel, the abbot agreed that Templars should collect no tithes, and should not admit parishioners to daily services or burial, but after hearing mass in their own parish church, they were permitted on solemn days and Sundays to hear votive masses in the chapel. Only passengers and strangers were permitted to make offerings there.Footnote 68 The Templars’ engagement of urban communities through their chapels, and the resentment that this occasionally generated from established religious groups, prefigured the role of the mendicant friars in towns, which produced similar complaints. The Templars also resembled the friars in the extra-mural locations of their houses.Footnote 69 In England, the two groups had particular links, as evidence taken at the trial shows that the Templars were relying on friars to act as their priests, conducting services and hearing confessions, as the Templars had only 11 priests of their own in England at the time of their arrest.Footnote 70

As the physical bases for the spiritual services that they offered, the Templars invested significantly in many of their urban chapels, although the level of expenditure made in the New Temple Church in London, consecrated in 1185, which included the use of Purbeck marble, was not paralleled in other contemporary Templar houses in western Europe. The round nave was a distinctive architectural feature of several earlier Templar chapels, including those of the Old and New Temple in London, Bristol, Dover and at the rural preceptories of Temple Bruer and Garway (Heref.).Footnote 71 The rebuilding of the chancel of New Temple Church in 1240 as a three-aisled rectangular structure was also unique within the Order, and probably reflects royal involvement, notably the intention to use the choir as a tomb for Henry III. Although the king was interred in Westminster Abbey, the church was a place of burial for nobles who were probably patrons of the order, notably William Marshal, fourth earl of Pembroke (c. 1146–1219), laid under a military effigy in the nave.Footnote 72 Like the original layout of the New Temple Church, the early twelfth-century Templar church at Bristol comprised a round nave and a chancel terminating in a semi-circular apse, with a western porch. In the late thirteenth or early fourteenth centuries, the apsidal chancel was replaced with a longer rectangular chancel with a chapel on its north side, thought to be that dedicated to St Katherine, which was granted to Bristol's company of weavers by Edward I in 1299.Footnote 73 On Western Heights above Dover are the remains of a chapel with a circular nave of 33 feet in diameter and a rectangular chancel (Figure 2). This has been linked with the Templars, although other suggestions include a wayside shrine, or a cliff-top chapel built as a navigation marker for mariners.Footnote 74 Certainly the antiquary John Leland observed in the 1540s that on the top of the high cliffs in Dover there was a ruined tower, which had been a lighthouse or beacon for ships out at sea, ‘and thereby was a place of Templarys’.Footnote 75 At York, the Templars received the twelfth-century chapel built for York Castle, separated from the castle by a water-filled moat, when a royal chapel was built within the gatehouse of Clifford's Tower in 1246. There was a cleric described as chaplain of the Castle Mills in 1292, and in 1308 the chapel's furnishings included a gilt chalice worth 100s, nine service books and vestments and ornaments.Footnote 76 The Templars’ church at Dunwich was described in 1631 as having been a fine building, with a vaulted nave and lead-covered aisles. It was styled in wills as ‘the Temple of Our Lady in Dunwich’ and remained in use until the dissolution of the order of the Hospitallers in 1540.Footnote 77 In 1308, the furnishings included a pair of organs, vestments, two gilt chalices and service books.Footnote 78 The inventories compiled in 1308 show the Templars’ urban residences in England were very sparsely furnished, with only the chapels like those at Dunwich and York having items of any significant value.

Figure 2. Possible Templar chapel at Western Heights, Dover. © The author.

The enduring presence of the Templars’ physical infrastructure within the urban fabric is evident from the continued use of many of their chapels after the dissolution of the Order. At Dunwich and Warwick, the chapels were used by the Knights Hospitaller, a rival Military Order who gained many of the Templars’ former estates. The Templar chapel at York became a royal free chapel, known as ‘king's chapel’, and after a period of neglect it formed the base in 1447 for the guild of St Christopher and St George. When the guilds were suppressed in 1549, it was acquired by York corporation and the upper parts dismantled and had various later uses as a house of correction, a workhouse, a workshop for weaving and finally the Windmill Inn, before being demolished in 1856 (Figure 3).Footnote 79 At Bristol, the nave of Temple Church was rebuilt in the later fourteenth century and the tower was added around 1460. Provision was made for chantry priests, and burials of local parishioners in the church and cemetery became frequent. By the late fifteenth century, the mayor, sheriff and other members of the city council joined the company of weavers at the feast of St Katherine, attending services in their chapel, processing around the city and returning to the church for mass.Footnote 80 Temple Church continued to serve its parish until it suffered severe bomb damage in 1940.

Figure 3. Remains of the Templar chapel at St George's Field, York, early 1850s. The original stonework of the chapel used by the Templars incorporated into the Windmill Inn. Clifford's Tower of York Castle in the background. © City of York Council / Explore York Libraries and Archives Mutual Ltd.

Property holders

Recent research has highlighted the strength of the property market in medieval provincial towns, and how many religious institutions became involved in urban property markets, often as a result of their foundation endowments and property gifted by benefactors, but also through conscious investment decisions. In Cambridge, for example, in addition to the large portfolios held by the town's Benedictine nunnery of St Radegund and Augustinan canons of Barnwell, around 30 other religious houses held property in the town.Footnote 81 The one important exception was the mendicant friars, who could not own property and relied on alms and bequests for their subsistence. The 1185 Inquest shows that the Templars had landholding interests in towns stretching from Bristol to York, and had received gifts of urban property from the crown, local lords and townspeople. The Templar urban estates appear to have supported a range of economic activities, as tenants with occupational surnames were to be found on the Templar holdings at Bristol, London, Oxford, Strood and Warwick, as well as in the new towns of Baldock and Witham (see Table 1). Some of these inhabitants may have had multiple occupations: at Strood, 20 tenants paid a penny when they turned their houses into taverns.Footnote 82 Many of these urban estates grew over the following century as the Order obtained additional properties and privileges. In the small Lincolnshire town of Grantham, for example, the Templars held at least 5 tofts in 1185, but by 1275 they had acquired 14 tofts and the assize of bread and ale.Footnote 83 Nonetheless, in numerical and monetary terms, the urban estates remained a very small proportion of the Templars’ overall landholdings. In Lincolnshire in 1185, the Order held over 17,000 acres in 167 settlements, of which the urban holdings of Lincoln, Boston, Grimsby and Grantham formed only a very small part. In 1308, the income drawn from York amounted to less than 1 per cent of the total income drawn from estates in the county.Footnote 84

Among the varied sources of urban income, the most valuable for the Order were often their mills. Castle Mills at York were let for the exceptionally large sum of 15½ marks (£10 6s 8d) in 1185. Mills at Hackney and Leyton were each worth 26s 8d per annum in 1331, and Widefleet Manor in Southwark possessed four mills, which were tide-mills located on the Thames.Footnote 85 By 1308, though, these mills were often neglected. The London watermill on the Fleet was written off by the crown, and timbers dragged from the river to the New Temple to be sold, an operation that cost more than it raised from the proceeds. Three nearby sites were vacant, causing a loss of 30s 4d per annum. The Templars’ property in Southwark included one house so dilapidated and ruined that its upkeep would cost more than it was worth, as well as three cottages and six water mills, also mostly requiring repair.Footnote 86 The Templars’ fulling mill at Witham was also derelict in 1308 and royal officials spent 100s repairing this mill and providing new millstones for watermills there.Footnote 87 As these had been valuable assets despite their neglect, the crown, when it acquired these properties, often considered it worthwhile to invest in their repair. In 1309, the crown's official began repairing the mills at Southwark, and further works were carried out in 1311 and 1312. The mills at York had been reportedly in great need of repair when held by the Templars, and were subsequently neglected by some of the keepers, and the wheels were carried away by a great flood in 1316. The sheriff was ordered to repair them in 1320.Footnote 88 Nor was decaying property confined to the Templars’ urban properties. The windmill at Rothley produced no profit as it was so broken down, and buildings at Gislingham (Suff.) were so ruinous that they could not be repaired without great expense.Footnote 89 The value of the mills as assets to the Templars and their successors suggests that the Order may have concentrated its investment in acquiring these assets, even if they could not later afford to maintain them fully, and there may be parallels with the Cistercians who acquired property that had a productive element, including corn mills, fulling mills and saltpans, that could support the infrastructure of their houses.Footnote 90

The practical value of some urban property may have been more important to monastic orders than the income it generated, particularly property in port towns, from which produce could be exported and supplies procured. The export of wool to Flanders from east coast ports was a particularly valuable commodity for the Cistercians, notably at Boston, where Melrose Abbey in the Scottish borders, as well as many Lincolnshire and Yorkshire monasteries, acquired property.Footnote 91 The Templars contracted to supply wool from the Lincolnshire houses of Temple Bruer, Eagle and Willoughton to the Bardi and Portenare merchants in 1308, which may have been exported through Boston.Footnote 92 The Templars held two tofts in Boston in 1185, one in demesne, which, like the Cistercian property, may have served as a base to conduct business with merchants, particularly during the major fair that took place in the town.Footnote 93 The Templar property in the port towns of Dunwich, Shoreham and Dover may have served a similar function.

Urban lordship

Lordship within towns, through powers such as the control over entry and exit, the transfer of property and the issues of justice, was, like the lordship of rural manors, an important source of revenue for many monastic houses. There were 20 English boroughs owned by Benedictine houses, and 5 by Augustinian houses.Footnote 94 Like other religious orders, the Templars jealously guarded their jurisdictional rights within towns, as the example of Bristol highlights. At the Temple Fee, which was separately tallaged until 1305, there were ongoing disputes with the Bristol and county authorities. In 1221, the Templars claimed that they should answer before justices in Somerset rather than to Bristol, and in 1325 the mayor and commonalty of Bristol complained to parliament about this anomaly, which led to people from Bristol evading the sheriff of Gloucester by simply moving their goods across the river to the Temple Fee.Footnote 95 Additionally, the Templars claimed many liberties in the market of Bristol where they held tenements.Footnote 96 The Templars also benefited from rights granted by the crown. These included the right to have one man in each borough called a hospes or guest who was to be free from tallage and exactions.Footnote 97 At Temple Normanton near Chesterfield, the 1185 Inquest recorded 5s from ‘Our host of the King's fee’.Footnote 98

These jurisdictional privileges could outlive the Order. The existence of a sanctuary at the Templars’ former manor at Southwark, first recorded in 1420, presumably derived from a papal mandate protecting the Templars’ houses in 1200.Footnote 99 Although the Temple Fee came under Bristol's jurisdiction in 1373, a perception that it was not entirely part of the town persisted, as shown in the language used in a dispute in 1543–44 over the Candlemas Fair, which presented Redcliffe as separate from the rest of Bristol.Footnote 100 The Templars’ urban privileges could not always be obtained by their successors though. At Baldock, while the master of the Templars claimed in 1287 the view of frankpledge, freedom for all pleas, his own gaol and the assize of bread and ale,Footnote 101 when the custodian of the Templars’ lands, Geoffrey de la Lee, attempted in 1312 to hold the view of frankpledge, the weights and measures were forcibly taken from the bailiffs.Footnote 102 Henry II had granted the Order a mark every year from every sheriff in England, and a mark from every city, town or castle paying the king £100 or more annually, which in the 1320s the Hospitallers complained was being withheld from them.Footnote 103

Conclusion

The Knights Templar had a significant impact on urban life in medieval England, which has not received the scholarly attention that its social and economic significance merits. The Order had bases in the leading urban centres of London, Bristol and York, the county town of Warwick, the ports of Boston, Dunwich, Shoreham and possibly Dover and the small towns of Strood and Wetherby. Rents were also collected from property holdings in Chesterfield, Derby, Grantham, Lincoln, Newark, Nottingham and Oxford, although the Order's income overwhelmingly came from rural estates. A number of Templar chapels provided services for their wider urban communities, and the Order's urban lordships operated with jurisdictions independent from adjacent town governments. Although at the time of their arrest, some of the Order's urban estates seem to have been poorly maintained, this neglect was also apparent on some of the rural estates. The Templars’ urban interests should be seen in the wider context that fourteenth-century England remained a predominantly rural society, with more than three-quarters of the population living in the countryside.

The Templars’ urban foundation at Temple Fee grew to be an important part of Bristol, while Baldock, Witham and Wetherby developed as thriving market towns. The Templars obtained grants of markets and fairs at these and other locations. Although the settlements of South Cave, Temple Balsall, Temple Bruer and Rothley never developed significantly urban characteristics, this may not have been the Templars’ goal. Recent research has suggested that small boroughs like these should be regarded as adaptable economic zones where landowners could respond to commercial expansion or contraction.Footnote 104 They provided marketing outlets for agricultural produce from Templar demesne lands. Similarly, the acquisition of urban property in port towns may have reflected the Order's business interests, notably the export of wool. Like the Cistercian order, the Templars’ urban foundations were relatively limited, and more important was their acquisition of property in established centres to facilitate trade, provide temporary lodging and as a source of revenue. The small size of Templar preceptories meant that, unlike many larger urban monasteries, they never provided significant consumer demand within the town or its hinterland. Urban preceptories were generally located in extra-mural locations, like friaries, and the provision of spiritual services by the Templars resembled those of the mendicant friars, on whose priests they partially came to depend by the early fourteenth century.

The Order's legacy to the urban fabric was arguably their most significant impact within medieval English towns. Templar chapels at Bristol, Dunwich, Warwick and York continued in use after the Order's suppression. Templar lordships retained separate jurisdictions into the later medieval period in Warwick and Southwark. Even today, place-names and street-names continue to testify to the Order's presence, not least at two of London's Inns of Court and at Bristol's main railway station. While their presence may not have been as widespread as several other religious orders, notably the Benedictines, the English Templars deserve consideration as effective urban promoters and investors as well as productive rural landowners.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Dr Catherine Casson and the anonymous referees for their comments.