North-Eastern North America, 1779: The Sullivan–Clinton Expedition and a War of Households

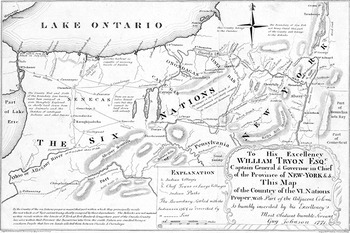

In 1779, at the height of the American Revolution, the American high command decided to destroy the power of the Six Nations in north-eastern North America. The contiguous territories of six allied Haudenosaunee nations, the Seneca, whose lands lay furthest from European settlement, the Onondaga, the Tuscarora, the Cayuga, the Oneida and the Kanyen’kehà:ka (Mohawk; Kanienke’há:ka), ‘keepers of the Eastern door’, whose territories were closest to those of Europeans and indeed overlapped with them, lay in the western and northern regions of what is today in American terms the state of New York. In 1771, before what he would come to see as the great disasters of the American Revolution, Guy Johnson, son-in-law of local magnate and Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern district of the Indian Department, Sir William Johnson, drew a map (Map I.1).

Map I.1 Guy Johnson, ‘Map of the Country of the VI Nations’ (1771).

Commanded by Major General John Sullivan and Brigadier General James Clinton, the American forces aimed to destroy the homes and food supplies of the hitherto more insulated western Six Nations in order to drive them from their homelands and to neutralize the Six Nations as a whole as a military threat to frontier settlements. This was part of the bitter frontier warfare of the opening years of the Revolution in New York and in Six Nations lands, which had included attacks on settlements and on civilians, and in which both sides committed human rights abuses. Nonetheless, the Sullivan campaign was of a different order of magnitude. It was consonant with American removal policy elsewhere during the Revolution, and with the settler quest to gain more land.Footnote 1 The campaign drove into the lands of the Senecas, Cayugas and Onondagas.Footnote 2 At least forty settlements were destroyed. The invaders killed domestic animals and burned all the crops they could find, including at least 160,000 bushels of corn.Footnote 3

The campaign was not merely another raid but a major engineering effort. It required building roads in order to move supplies, horses and several thousand troops into densely forested regions. It also demanded the construction of a fort and of dams to facilitate the large-scale movement of shipping.Footnote 4 This was a slow-motion invasion, pioneered by engineers. As such, the expedition could be and was seen by many white observers as a movement of ‘civilization’ into the ‘wilderness’.Footnote 5 It was the construction of roads and forts, and not only the ethnic cleansing of the campaign, that opened Iroquoia to white settlement, and eventually facilitated the subsequent westward movement of the nascent American republic after the end of the war, even if it was British betrayal at the negotiating table that sealed the fate of the lands of the Haudenosaunee.Footnote 6

Despite the ideas many held about civilization and wilderness, the soldiers were surprised to find that the Six Nations had built many houses that blended Haudenosaunee and European styles, that their dwellings were often wealthier than those of frontier settlers, and that they had well-stocked orchards and rich fields of corn and vegetables. ‘Their houses are large and elegant; some beautifully painted; their tombs likewise, especially of their chief warriors, are beautifully painted boxes, which they build over the grave, of planks hewn out of timber’, Lieutenant Charles Neukerk observed about the ‘fine town’ of Kandaia on 5 September 1779, for example.Footnote 7 The Haudenosaunee were fighting on both sides of the revolution, so this invasion was also an attack on the British and on joint white-Haudenosaunee forces; guides included some American-allied members of the Six Nations, and armies on both sides adopted some Indigenous fighting techniques.Footnote 8 Distinctions between groups were hardened by warfare, and yet also at times more blurred both culturally and politically than the racialized ideology of civilization against wilderness would suggest.

Neukerk described in bureaucratic detail the burning of towns and food. On 15 September 1779, for example:

[t]his morning the whole army paraded, at 6 o’clock to destroy the corn &c about this place, which could be done no other way but by gathering the corn in the houses & setting fire to them. Here we likewise found a great quantity of corn gathered in houses by the savages. At 3 o’clock in the afternoon we completed the destruction of this place […].Footnote 9

American lawyer and amateur historian W.W. Campbell reprinted Neukerk’s journal in his own 1833 history Annals of Tryon County. ‘To a person reading the foregoing journal,’ he remarked with some evident discomfort, ‘it may seem that too much severity was exercised in the burning of the Indian towns, and that corn, &c was wantonly destroyed.’Footnote 10 Such actions were, however, he argued, necessary to bring an end to a war that had become a war of households: ‘their towns were their retreats, and from thence they made incursions into the settlements’.Footnote 11 The New York/Iroquoia campaigns of the American Revolution were in part about different groups trying to destroy each other's homes in a bitter contestation over land ownership. Their impact would be long-lasting: the campaigns resulted in a Six Nations exodus to British-held territory, turning the Haudenosaunee into refugees, while ironically opening the door for British negotiators to abandon Six Nations country to the Americans in 1783.Footnote 12

The invasion might, then, be seen as part of a war of households, triggered by the outbreak of the Revolution, in which tropes of difference needed to be mobilized to justify dispossession and in which ideas about families and domesticity played an important role. The ethnic cleansing of the Sullivan campaign sought to eradicate Haudenosaunee dwellings from the landscape and to destroy the traces of Haudenosaunee cultivation of the land. It stands, however, as only one example among many of the way in which warfare entrenched divisions between ‘white’ and ‘Indian’ in colonial New York during the frontier wars of the Revolution, in part through creating a sense of each as constituting incompatible households that needed to be destroyed. The white states that emerged on both sides of the new border from the ashes of conflict would frequently imagine whites and Indians as racially distinct and as at different levels of development. Difference was nonetheless fragile and needed to be constantly reinvented.

***

The Sullivan campaign was a small element, if a particularly brutal one, of a much larger process that lies at the heart of this book. From the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, settlers under the aegis of the British empire (or, in the case of the Americans, escaping the British empire) laid claim to what they often described as undeveloped ‘wastelands’ that would be transformed by settler colonialism. In the process, they steadily displaced people who have come to be referred to as ‘Indigenous’ – a term that contains within it a prior claim to invaded lands. These groups included numerous North American Indigenous peoples such as the Haudenosaunee; Australian Aboriginal peoples, including (to name just some whose members bore the early brunt of invasion and who will be discussed in this book) the Noongar of Western Australia, the Eora and Wiradjuri of New South Wales, or the Palawa of Van Diemen’s Land; the San and Khoekhoe in southern Africa; and the Maori in New Zealand. As this brief list suggests, groups were highly diverse, and their relative degrees of power varied. Nonetheless, the British often claimed that they had common characteristics, such as relying on hunting for subsistence or vulnerability in the face of ‘civilization’, and frequently described them as ‘aborigines’. Many descendants of these groups would by the twentieth century embrace a common identity as Indigenous. This book examines the entangled history of the conquest of Indigenous lands and the development of linkages between these very diverse peoples through the experience of colonialism between the 1770s and the 1830s.

How, however, to analyse such complicated processes? A key focus of this book is on family and kinship. More particularly, I trace the entangled lives and imperial careers of three families whose members played important roles, from a variety of subject positions, in the forging of new colonies and in interaction between Indigenous people and settlers in the British empire from the 1770s to the 1840s, particularly on colonial borderlands. One was a prominent North American Six Nations family, the Brants, who supported the British during the Revolution and later spearheaded migration to Upper Canada. Another was a British family, the Bannisters, a group of restlessly mobile siblings closely involved in colonial administration and settler expansion as well as in documenting violent abuse in the 1820s. A third, the Buxtons, were a prominent British political family who, in addition to fighting for the abolition of slavery, tried to reform the settler empire from its centre before supporting a form of colonialism in West Africa in the name of humanitarianism in the 1830s and early 1840s. I use evidence from the lives of family members to illuminate the entrenchment of settler colonialism, examining themes such as violence, the changing politics of kinship, the role of family networks in empire, debates about land and sovereignty, the relationship of humanitarianism to colonialism, and the emerging conception of ‘aboriginal’ as a transnational identity. The lives of individuals are also ways into closer examination of particular territories, as I follow family members from revolutionary America, to Upper Canada, Australia, southern Africa, Sierra Leone and Britain.

The Sullivan campaign was not only a turning point in this history in its own right, but also raises a number of themes pertinent to the period as a whole. First, the violence of the Sullivan campaign was typical of the wider history of settler colonialism over this period, not least in its attacks on civilians, including driving civilians from their land. We will see a significant repetition of such tactics, particularly by the police and the military, as we follow the empire through time and from one frontier to another. In all of the places covered by this study, from colonial North America to Australia to southern Africa, there was warfare as well as more quotidian conflict over land between commercial farmers and those prior occupants of the land who depended on hunting, pastoralism and/or subsistence farming. And in all places the line between civilians and combatants would be blurred.

At the same time, the British military also often either had Indigenous allies or hired Indigenous soldiers and policemen once the earliest phase of conflict was past. This is not to argue that there was consent to the occupation of land. On the contrary, the British empire’s appetite for soldiers and the lengths to which the empire went to obtain ‘loyal’ marksmen were part of wider patterns of violence. In the case of the Sullivan campaign, for example, Six Nations fighting on the side of the British were punished for a war that almost none of them wanted and in which they fought mostly to protect their own lands – and, as Barbara Graymont points out, the empire was not able to defend the lands of the Six Nations that alliance had put at risk.Footnote 13 Furthermore, loyalists might not remain loyal when pushed too far.Footnote 14 The painful complexity of loyalty and military allegiance will also be a key theme in this book, despite its difficulty.

Second, the exile of many of the Six Nations to Lachine or to Niagara, as well as the flight of many settlers from rural New York during the war, were part of wider patterns of disruption and mobility that scattered people like migrating birds across newly desolate landscapes.Footnote 15 There are many ironies in terms such as ‘settler’ and ‘Indigenous’, as settlers moved restlessly and Indigenous people were subject to removal. There is a further irony that the fluid ways in which many Indigenous societies moved over land, formed new groups and sought to incorporate outsiders would all be rendered difficult by the later intrusions of colonial states, the bureaucratic requirements of which came to require fixity and an imagined statistical precision. The themes of mobility, disruption and struggle over land will recur throughout this book.

A third crucial issue highlighted by the Sullivan campaign is that of economic transformation and associated ideological claims. Lands from which the Six Nations were displaced were commodified and turned into cash and credit in a growing capitalist economy. At the same time, these were already farmed and clearly embedded in an existing regional economy, and many houses were legible to western eyes as European-style dwellings. We will see that at least some among the Haudenosaunee wanted (however controversially) to invest in the London stock market, to get the best possible price for their lands and to derive rental income from former hunting grounds. They were often blocked from doing so. The colonial economy was racialized and marked by a drive to racial exclusion in most parts of the world examined by this study. It cannot, however, completely be understood in binary terms.

This does not mean, however, that the liberal responses to a racialized economy that we shall examine throughout this book, as colonial violence and racial discrimination were heatedly debated, were innocent of imperial intent. Several key figures in this study, including the former Attorney-General of New South Wales Saxe Bannister and the reformist MP Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, vigorously argued that the only way to have a moral colonialism without the warfare and ethnic cleansing typical of the American Revolution was to manage a consensual and non-violent transfer of sovereignty and to extend the benefits of a liberal state to all its inhabitants, including equal economic access. This was, I will argue, a key part of a blueprint for ‘moral colonialism’ that emerged by the end of the period under study in this book, and that would in turn become an important part of the justification for late nineteenth-century imperial expansion.

Family, Place and Settler Colonialism

How then does this book seek to accomplish its objectives? I structure the book both by family and by place, with some areas of overlap. The book is divided into three sections, turning around the three families studied. In turn, different chapters explore different locations within each section. The book moves across North America, Australia and Africa before turning in its final chapter to Britain.

We begin in the borderlands of New York/Iroquoia in the late eighteenth century before and after the Revolution. In starting in colonial America, I hope to bring the United States into conversation with other British settler colonies while also acknowledging the artificiality of national boundaries for North American Indigenous communities.Footnote 16 Joseph Brant (Thayendenaga) and his sister Mary or Molly (Konwatsi’tsiaiénni) were part of a Kanyen’kehà:ka or Mohawk community that was, not without significant internal controversy, in a military alliance with the British. The Brant family included white members. Most importantly, Molly Brant and her partner, Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of Indians for the northern district of the Indian Department of the British military, had eight children. Johnson used household power to control the frontier; this was, however, a type of power that would be rejected by settlers during the Revolution. Although many of the Six Nations fought on the British side during the American Revolution, others, particularly the Oneida and some Seneca, supported the Americans, with great costs in both cases, including the shattering of the Confederacy.

Joseph and Molly Brant and William Johnson are all well-known and indeed controversial historical figures. Their lives have been extensively studied, as has the complex role of the Haudenosaunee in the American Revolution.Footnote 17 I am not trying to write new biographies. Nonetheless, this work serves as a springboard for what follows, particularly given the importance for later events of competing historical memories of the Brants, of the Six Nations alliance with the British, and of Six Nations’ conceptions of sovereignty. A key contrast with later borderlands is the different nature of kinship relationships in a context in which Indigenous groups held greater power and were in closer diplomatic contact with the British than would be the case elsewhere. This analysis also requires asking about Haudenosaunee family structures, concepts of relationality and ways to incorporate new people, reflecting the stress on kinship placed by many scholars coming from an Indigenous studies perspective.

Although I am looking at elite and well-studied figures, I use sources such as oral histories recorded in the nineteenth century, wartime memoirs and local gossip in order to try to place them into the wider context of an uneasy borderland. I use family stories, for example, to argue that while on the one hand Joseph Brant’s participation in attacks on border settlements was taken as justification for ethnic cleansing and as proof of the impossibility of Indigenous-white coexistence, on the other hand other family memories from the New York borderlands suggest closer ties and imply that Brant himself may have tried to play to multiple audiences.Footnote 18

In Chapter 3, the book moves to Upper Canada. This follows the post-war movement of many Haudenosaunee to Upper Canada after the British Empire rewarded their allies by trading their lands to the new-born United States of America. Molly Brant’s daughters married prominent white men, as ‘white’ and ‘Indian’ increasingly became identities perceived as incompatible, despite the persistence of intermarriage. Joseph Brant, and later his son John, tried to negotiate what they saw as more ‘modern’ economic solutions for the Six Nations, although they were also entangled in a corrupt economic environment and were embroiled in community debates over the best path forward, including how far to engage with the white state. It may be telling that one of Joseph Brant’s other sons, Isaac, passionately opposed his father’s policies, tried to kill Joseph and was himself killed in the struggle. Through these vicissitudes, the Brants remained relatively elite. They were not typical, but many of the dilemmas and difficulties they confronted were, including the declining viability of strategies oriented to incorporation and management of colonists and the loss of Indigenous sovereignty. In Chapter 4, I analyse how Brant family members John Brant and Robert Kerr took their claims for land in Grand River directly to London in the early 1820s, strategically performing an identity as Mohawk warriors despite the fact that Kerr in other contexts presented himself as a Scottish businessman.

In making land claims, Brant and Kerr were assisted in Upper Canada and in London by two members of the Bannister family. In the second section of the book, I shift gears and move to focus on the imperial activities of three Bannister brothers and to a lesser extent of their sisters. Originally from Sussex, the Bannister siblings were dedicated to the pursuit of colonial fortune overseas throughout the early nineteenth century. Saxe, John William and Thomas Bannister, three restlessly mobile brothers, carried out colonial activity of one kind or another in the 1820s and 1830s in Upper Canada, New South Wales, Van Diemen’s Land, Victoria, Western Australia, southern Africa, and Sierra Leone; Harriet and Mary Anne accompanied Saxe to New South Wales and then settled in Van Diemen’s Land. The Bannisters had their own conceptions of kinship as a gentry family in financial peril: they believed they should collectively have more status than they actually did, and they looked to the new opportunities opened up by settler colonialism to make up the gap. In doing so, Saxe and John William tried to claim authority as men who knew and could help Indigenous peoples. The siblings chased financial advantage across the far-flung imperial world even as the eldest, Saxe, penned important attacks on British policy towards Indigenous peoples. He uncovered abuses in New South Wales and South Africa, not least the murder of an Indigenous man in police custody that locals tried to cover up. The Bannisters sought to ride the waves both of settler colonialism and of liberal reform, not seeing them as incommensurate. In that sense, they provide a case study of the interaction between liberalism and empire, which, as my work suggests and as others have argued, proved eminently compatible in the early nineteenth century.Footnote 19 We will see that Saxe Bannister in particular hoped that new and better versions of empire could end the genocidal tendencies of settler colonialism, even as he actively and fervently promoted the annexation and colonization of Natal.

In the third and final section of the book, I turn to the Buxtons, a more securely elite British family involved in reformist politics in the late 1820s and 1830s. The family patriarch, Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, was a Whig MP and a key advocate for the abolition of slavery. Most crucially, he piloted the bill for the abolition of slavery through the House of Commons in 1833. Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton’s work was enabled by the support and activism of his family, particularly his daughter Priscilla, his wife Hannah and Anna Gurney, the partner of his sister Sarah Maria.Footnote 20 It is on Priscilla that this final section focuses most closely. In contrast to the scattered and combative Bannisters, the Buxtons drew on interconnected family networks that amplified the power of particular families: they were key players in a wider network of elite humanitarian families in Britain, many with Quaker roots, who fought for the abolition of slavery in the 1820s and early 1830s, and whose female members formed crucial bonds. From the mid-1830s to the early 1840s, the Buxtons took up Indigenous rights as they understood them as a political crusade, influenced by their previous work on abolition. In looking at the information networks in which Priscilla and other Buxton family members were involved, I trace the movement of information about frontier killing in South Africa from Xhosa activists or Khoekhoe soldiers to the imperial centre; I also trace the counternarratives that colonial settlers and officials produced in response as the politics of information exploded in hearings before the House of Commons Select Committee on Aborigines.

In the final chapter of the book, I use the example of the Niger Expedition of 1841–1842, an act of would-be humanitarianism enthusiastically sponsored by the Buxtons, to illustrate the ways in which early nineteenth-century humanitarianism in many respects came to serve the ends of colonialism. At the same time, lands of the Haudenosaunee in Upper Canada were ‘reduced’ as the colonial state reimagined military allies as dependents in need of civilization. These two examples illustrate, I will argue, crucial trajectories in the history of settler colonialism and illuminate the paradoxes of imperial reform.

Connected Lives, Entangled Colonies

Overall, then, this book uses microcosmic analyses to illuminate a macroscopic process: the project of British settler colonialism as it sprawled across time and space during this critical period of the creation and consolidation of settler states. The lives of many of the people that I discuss were often only peripherally linked (and contrasts are often revealing). Their lives nonetheless intersected in multiple and multifaceted ways, brokered by colonialism.

Take, for example, the relationship between members of the Brant and Bannister families. The colonial imaginary of the Bannister brothers was shaped by their contact with Brant family members in the 1810s and 1820s over land claims in Upper Canada. John William Bannister knew John Brant in Upper Canada, possibly through colonial reform movements. John Brant tried to use Saxe Bannister to get a hearing at the Colonial Office in 1821; Saxe Bannister tried to use his connection to John Brant to get a job. We are in fact witnessing the birth of the humanitarian ‘expert’. In extensive written work over many years, in which he railed against colonial violence, Saxe Bannister took Joseph Brant as proof of the feasibility of a moral colonialism. He also presented himself as a colonial expert on the basis of his interaction with the Six Nations. As a mobile colonial subject with a strong ideological agenda, it seems likely that Saxe Bannister brought knowledge of Indigenous North American affairs to Australia and South Africa, and served as a conduit of information from one colonized community to another – or so I will argue in this book. Bannister and Buxton collaborated, although they had a slightly uneasy relationship; Bannister worked hard to persuade Buxton to adopt his view of colonial affairs, and to embrace the supposed inevitability of settler colonialism.

More broadly, members of these families were bound together by participation in common processes. One was debate about the overall direction of the settler empire. Stung by accusations of using brutal warfare against American civilians through their deployment of Indigenous allies during the Revolution, not least by arguments made by Brant family members, a number of British commentators, including Saxe Bannister and Priscilla and Thomas Fowell Buxton, tried to define Britain as more moral than the rebel Americans and more supportive of the welfare of enslaved and Indigenous peoples. American attacks on Indigenous peoples during the war became a prime example. This helped to drive an elite concern to create a supposedly more ‘moral’ and better ordered empire (however unfulfilled that expectation), which will also be a key theme of this book.Footnote 21

Another point of contact is the involvement of several family members with the military, related to the more general interaction of all three of these families with colonial violence. The British military consistently sought out Indigenous military allies, from Haudenosaunee warriors to Khoekhoe members of the Cape militia, to formerly enslaved people recruited for the British army in Sierra Leone. Joseph Brant was a colonel in the British army during the Revolution, and was therefore part of the British strategy of using ‘rangers’, or small units deploying Indigenous fighting techniques and staffed in part by Indigenous warriors. From a British administrative perspective the Six Nations were granted land in Upper Canada in part out of fear of Indigenous military resistance to the post-Revolution settlement but also because they could be conceptualized as demobilized soldiers, to whom colonial land was traditionally given. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, the military, particularly the navy, played an outsize role in locating, creating and governing new colonies. John William Bannister joined the British navy at the age of nine, settling in Upper Canada after being demobilized, like many other former navy officers. Thomas Bannister was a low-ranking officer in the Fifteenth Regiment of Foot before he became a colonist. Even the lawyer Saxe Bannister joined a Sussex militia at the tail end of the Napoleonic wars and tried throughout his life to present himself as a potential soldier, however unconvincingly. Saxe urged the creation of a settlement for the Khoekhoe in southern Africa, similarly seeing them as deserving demobilized soldiers (as he imagined the Haudenosaunee to be). The Buxtons were unconnected to the British military, but this may help explain why they were such strong supporters of missionary and metropolitan control of the settler empire: a very real question in the 1830s was which institutions would in fact rule the emerging colonial empire. Priscilla Buxton fought to get the military out of the business of running the Xhosa borderlands through the barrel of a gun. The violence of the empire was not only the openly violent conflict of colonial frontiers that gave a sense of urgency to imperial reforms. Violence also included the pressure the empire placed on subalterns to fight other subalterns.Footnote 22

While this book spends considerable time exploring violence in particular colonies, including resistance and processes by which violence was normalized, it also considers violence as ‘imperial’, in that it was part of a wider imperial system. The violence of settler colonialism is increasingly recognized and indeed commemorated, despite countervailing amnesia and popular resistance, exemplified in the so-called history wars in Australia.Footnote 23 This commemoration tends to happen at a national level, however, as successor governments assume colonial guilt.Footnote 24 The entangled histories of the involvement of three families in imperial violence (whether as critics, participants or members of the organized military) underscores the ways in which violence united the empire in a parallel history of the unspoken.

A final point I want to emphasize in this brief overview is that to write about families in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries is of course to write about patriarchy. In a quite literal sense, much of this book is focused on patriarchs and would-be patriarchs. Elite masculinity is particularly central to this book. So too are households headed by patriarchs such as William Johnson and Thomas Fowell Buxton: they were local centres of power as well as nodes of imperial power, and they could include Indigenous clients. Women who headed households, such as Anna Gurney, the partner of Thomas Fowell’s sister, also had a form of power, however contingent. As states tried to curtail both household and family power, this in some respects reduced the limited form of power that some women and a few Indigenous people had accessed via the patriarchal household or via relationships with elite white men.

Periodization and Change through Time

Despite the recurrence of particular themes across time and space, there were significant changes to the nature of settler colonialism over this period. C.A. Bayly famously termed 1780 to 1830 Britain’s ‘imperial meridian’, a period characterized, in his view, by the continuing dominance of aristocratic paternalism and the ongoing influence of the men who had fought in the Napoleonic Wars.Footnote 25 On his reading, this was a crucial period of the expansion and consolidation of British power in the wake of the loss of America, driven not so much by liberalism as by a small agrarian ruling class, informed by aristocratic values and Anglicanism. There is room to question the cultural predominance of aristocratic agrarianism in this period, given the effectiveness of ongoing challenges from liberals and evangelicals and indeed the liberalism of some aristocrats (as some of the evidence in this book suggests), but on balance the evidence presented here confirms Bayly’s insight about the relative coherence of this period and the importance of challenges in the 1830s.

While the empire is often described as undergoing a ‘swing to the east’ over this period, these years also saw the creation and expansion of anglophone settler colonies, driven in part by the importance of the navy.Footnote 26 The significance of this settler explosion is all the more evident if American expansion is included in the same frame.Footnote 27 Between 1787 and 1843, the British government founded or significantly developed settler colonial states on the continent of Australia (New South Wales in 1787, followed by several others), in New Zealand (1840), in Upper Canada (created as its own province in 1791) and in the Cape Colony (confirmed to Britain in 1814) and Natal (1843) in southern Africa. Much of this expansion happened before the expansion of the franchise in 1832. It occasioned significant unease, as this book will show, in at least some quarters. By the 1840s, however, most Britons accepted settler colonialism and saw it as largely beneficial.

I argue that there was a shift, particularly in North America, from the willingness to use family biopower as a core technique of governance, potentially permitting alliances between Indigenous and British elites (in however fragile a fashion), to bureaucratic state management by colonial states that were coded as neutral but were in practice racialized. This was linked to decline through time in the capacity of Indigenous people to use their own strategies to assimilate and manage outsiders. Most of the people with whom the British came into contact had their own ways to incorporate outsiders, such as sexual exchange or allowing outsiders to occupy land in return for loyalty to a leader. For example, we shall see that at different ends of the earth and in very different contexts, both the Haudenosaunee of eastern North America and the Zulu of southern Africa tried to manage colonialism in part through trying to make kin and allies or subordinates of outsiders.Footnote 28 These were assimilative political strategies based on an assumption that the dominant group could incorporate non-members into existing structures. In contrast, as Indigenous power declined, white settlers claimed the direction of states, often also repudiating white elite family power in the process of affirming their own status.Footnote 29

The shifts in modes of governance this book explores included the increasing bureaucratization of government structures at the micro level, and, at the transnational level, the growth of nation states as a loci of power. Such developments, I suggest, were accompanied both by changing political roles for families (loosely defined as kinship groups rather than the nuclear family alone) and by a changing set of metaphors about the relationships between states, families and Indigenous peoples.Footnote 30 For example, settlers often came to define themselves as ‘the people’ and their states as a form of political family. In the process, they repudiated the power of actual families and frequently broke (or decided to forget) kinship ties with Indigenous peoples. The rise of settler democracy through the early nineteenth century sidelined Indigenous power, which was often reimagined as a form of corruption, linked to older forms of family-based governance, the repudiation of which (however illusory) was in turn crucial to the development of politically liberal settler states. This facilitated a populist rejection of such alliances as existed between elites and Indigenous peoples, particularly Indigenous elites: they could both be cast as corrupt and as opposing the will of settler ‘majorities’.

A significant issue at play in the book is therefore the role that family governance was broadly thought of as playing in societies conceived of as not yet ‘civilized’. Since many of the Indigenous peoples whom the British colonized prioritized on-the-ground relationships – and often tried to neutralize colonizers by developing family ties and using kinship metaphors in diplomacy – their previous relationships with colonizers, including treaties and trust mechanisms, could be dismissed as pre-modern and corrupt, with corruption having a whiff of the not-modern about it. It is arguable that the repudiation of treaties with Indigenous groups to cynical ends was all the easier. Certainly, settler states today continue to live with the legacies of different ways of understanding past treaties, including different understandings of the relationships they enshrined.

Context and Some Pertinent Scholarship

In making these arguments, this book draws on a wide and diverse range of sources. I have been privileged to read across ‘national’ areas and to be inspired by several different fields; my indebtedness will become clear. At the same time, some comparative transnational scholarship has proved particularly helpful in thinking about linkages between regions

One of the significant transnational fields within which this book is situated is the burgeoning field of study loosely termed settler colonial studies. Settler colonial studies in fact covers a multiplicity of themes. The field has nonetheless been shaped in distinctive ways through the early influence of historians coming on the one hand from Australian history and on the other hand from genocide studies – and in several cases, such as those of Benjamin Madley, Dirk Moses and Lorenzo Veracini, making key interventions in both fields.Footnote 31 Patrick Wolfe influentially claimed in a seminal 2006 article that settler colonialism is inherently genocidal because it requires a land without people, and therefore works either to kill prior occupants or to assimilate them into colonial culture to the point that they lose a distinct identity and are no longer a threat.Footnote 32 In this paradigm, settler colonialism is different from other forms of colonialism, having as its definitional characteristic the need to eliminate Indigenous people.Footnote 33 Settler colonial studies emphasizes process over the intention of individuals. To make such arguments requires taking a stance in debates over the definition of genocide, seeing cultural colonialism and forced assimilation as also elements of genocide.Footnote 34 In this optic, settler colonialism is, in Veracini’s words, both a ‘distinct form of domination’ with its own characteristics and a form that has a broad and deep history.Footnote 35 ‘Settler’ and ‘Indigenous’ thus become capacious transnational and transhistorical categories.

There has been some critical evaluation of settler colonial studies in recent years, not least by some First Nations scholars concerned about issues such as the creation of a ‘monolithic native/settler binary’ and the need to adapt the theory to ‘accommodate the role of Indigenous agency and resistance’, in the words of Shino Konishi, or simply the desire for an Indigenous history that does not revolve around settler domination.Footnote 36 A crucial question is therefore that of how also to centre and promote Indigenous resurgence.Footnote 37

As evidence presented in this book in fact suggests, a tight model is only partially generalizable across diverse areas of settlement, particularly given different demographic realities, despite the political and intellectual work done by the idea of continuity both then and subsequently. Furthermore, too teleological a model arguably does not leave a lot of space to analyse changing relationships in the aftermath of the initial period of conquest, including ways in which Indigenous peoples managed at times to impose their own political terms, in however constrained a manner, on colonists. Labour extraction could and did coexist with the theft of land; military recruitment is one often overlooked example. Having said that, settler colonial studies makes crucial interventions, including expanding the definition of violence and emphasizing continuities between assimilation policy and physical violence. The field of settler colonial studies is constantly expanding and mutating, and it would be wrong to assume that it cannot incorporate a more flexible approach to the study of interaction.Footnote 38

Indigenous studies provides another framework for thinking about both local complexities and global connections. Indigenous studies explores the past and present of people defined as Indigenous across the world, paying attention to local realities while placing Indigenous people in global and comparative context – albeit without always resolving the tensions this raises. Indigenous studies tends to be more interdisciplinary than settler colonial studies, which currently focuses more tightly on historical analysis. Nonetheless, boundaries between the two fields are surely fluid. There are a number of methodological commitments classically associated with Indigenous studies approaches and its call to decolonize the academy, including working in partnership with communities, ideally carrying out work in service to the community and in interaction with Indigenous knowledge holders.Footnote 39 Given the diversity of Indigenous studies and its fluidity, it is difficult to single out a core contribution. Nonetheless, of particular importance to this project is the stress placed by multiple scholars on the importance of kinship and of place to Indigenous worldviews in a variety of contexts.Footnote 40 Kinship in this perspective might extend beyond literal kin and include the notion of the interrelatedness of all people, and of the human and the non-human. Aileen Moreton-Robinson argues that ‘relationality’ is ‘the interpretive and epistemic scaffolding shaping and supporting Indigenous social research and its standards are culturally specific and nuanced to the Indigenous researcher’s standpoint and the cultural context of the research’.Footnote 41 These insights are very helpful in thinking about issues such as what treaties might have meant to all participants or the incorporative strategies of pastoralists and hunters. They also impose humility, particularly on a scholar writing from the outside; I would like here to acknowledge my own limitations. I also want to acknowledge the call of thinkers such as Glen Coulthard not to define Indigenous people in relation to settlers.Footnote 42

A different form of potentially transregional analysis is suggested by scholarship on the history of the British Empire that asks about the role of families and of family networks in a variety of contexts. Rich studies include Catherine Hall’s seminal studies of Zachary and Thomas Macaulay and of the family legacies of slavery; Margot Finn’s scholarship on family politics in early modern South Asia; Emily Manktelow’s analysis of mission families in southern Africa; Elizabeth Buettner’s work on the families of the late imperial Raj; or Laura Ishiguro’s writing on family letters in British Columbia.Footnote 43 David Livesay argues convincingly for an expansive conception of the ‘Atlantic family’ that includes the mixed-race children of enslaved people and slave-owners, even as he demonstrates the cultural fluidity of conceptions of family.Footnote 44 The work of David Hancock and others has long shown the importance of kin to merchant networks, demonstrating the centrality of family to long-distance economic relationships.Footnote 45 The Quaker banking families to whom the Buxtons, my last family, were connected were linked by the trust relationships that came both from family ties and from shared religious practice and belief; this enabled them to participate in transnational banking and commerce, but it also created personal kinship ties that in turn helped the families work together on political causes such as abolition and prison reform. Family sociability in the British context was also a way to forge economic links and to grease a variety of transactions, from political activism to international banking.Footnote 46 All the families that I study used, or tried to use, family ties to economic advantage in an imperial context.

Another way in which family worked in empire during this period was through the political and economic uses of sexual relationships between colonizers and colonized, usually between settler men and Indigenous women. Adele Perry’s illuminating study of the Douglas-Connolly family in British Columbia, which explores the mixed white, Black and Indigenous ancestry of the family of the first governor of British Columbia, suggests among other things that multiracial families might find a common identity in imperial service.Footnote 47 At a less elite level, cross-cultural sexual partnerships were economically crucial in periods of resource extraction before the development of full-fledged white settlement; a prime example is the North American fur trade.Footnote 48 Family ties between white men and South Asian women were also important to the functioning of the East India Company.Footnote 49 Bearing this in mind, the relationship between Molly Brant and William Johnson that Chapter 1 discusses needs to be placed in the context of wider local and imperial patterns, including the anxiety interracial sexuality increasingly provoked further into the nineteenth century.Footnote 50 In thinking about such relationships, it is crucial to acknowledge the role of sexual exploitation in a context of racial and gender inequality as well as the vulnerability of Indigenous women to the politics of gender and generation within their own natal societies.Footnote 51 There was an enormous range in such partnerships, while at the same time casual sexual violence was also endemic on colonial frontiers, and competition over women was often a trigger for conflict between men.

The fact that such sexual partnerships were not always acknowledged in the communities of one or both of the partners does raise the question of what counts as ‘family’. In what sense was a sexual relationship in an imperial context about family (particularly when outside the bounds of ‘marriage’), rather than straightforward sexual exploitation? There is no clear answer to this question, which underscores the contextual nature of how ‘family’ might be understood. I use the term relatively loosely to describe a socially recognized kinship formation, without being precise about what this entailed. I also move between ‘family’ and ‘kinship’ as organizing concepts in recognition of the culturally determined nature of what diverse societies consider ‘family’ to be. In this sense, a publicly recognized sexual partnership might be seen as a family relationship, whereas an entirely covert sexual relationship arguably might not be. Things are not, however, simple. In general, shifts in British attitudes towards sexual relationships between colonizers and colonized surely reflected changing conceptions of what counted as family. In the context of the British Empire, attitudes changed significantly over the period analysed in this book, from the late eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries. Changes were also linked to the declining capacity of Indigenous societies to impose their own understandings of the politics of kinship and to shifting patterns of resource extraction. This form of family formation would be deployed by Molly Brant, largely ignored by Saxe Bannister and conceptualized as exploitative by the women of the Buxton family.

One of the reasons that family mattered as a vector of political power between the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was that family networks, broadly defined, enabled people to communicate and act across imperial spaces. Distance might be shrunk by letters, news and personal visits, by small or large financial transactions, by relationships of trust or exchanges of gossip. Studying imperial families therefore opens the door to what some scholars have termed ‘connected history’, or histoire croisée.Footnote 52 Such an approach enables comparison between events in different spaces, but does so through showing entanglement across space. I am interested in families in part because the intimate scale of the family spanned the vast space of interconnected colonies. Families are therefore an important way to study empire as a networked space, linked by personal as well as by institutional networks, but also characterized by profound, racialized ignorance.

This approach is in line with work in imperial and global history that seeks to make sense of how imperialism and globalization tied together space without reducing individual complexity to artificial abstractions and bloodless arguments about structure.Footnote 53 Important work over the past two decades has focused on networks and the ways in which networks brought diverse colonies into conversation with one another. This is a hallmark of what has been called the ‘new imperial history’ (although of course ‘new’ does tend over time to become older). Such analysis tries to escape from an approach that focuses on the dichotomous relationship between colony and metropole in order to see more complex relationships between diverse ‘nodes’ and ‘circuits’ in imperial networks, to borrow terms deployed by Alan Lester.Footnote 54 The approach opens the door to fruitful comparisons between settler colonies, rather than solely in relationship to London.Footnote 55

The enormous problem of the limitation of archival sources in regard to colonial history is evident in the analysis of networks. The risk of a networked approach focused on the movement of people (perhaps more than in the case of the movement of goods) is that it is easiest to study the white elites who left the most visible archival traces.Footnote 56 The concept of a Black Atlantic and a focus on Black mobility throughout the early modern Atlantic World has long stood as a counterexample to the predominance of white subjects in studies of imperial networks.Footnote 57 Is it possible similarly to analyse Indigenous networks, even if Indigenous people were less mobile across the seas linking imperial spaces than enslaved people? Is it possible to write a networked Indigenous history for the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that might, for example, consider the ways in which Indigenous people attempted to forge links between colonized peoples in different societies, or came to think of themselves as potentially holding things in common, even before the more evident global networks of the mid-twentieth century and beyond?Footnote 58 One approach has been to study Indigenous people who were mobile, as Coll Thrush does in his illuminating history of Indigenous peoples in Britain.Footnote 59 More generally, a number of scholars have begun to explore the history of Indigenous networks within and beyond empire, as exemplified in the 2014 collection edited by Jane Carey and Jane Lydon, Indigenous Networks: Mobility, Connections and Exchange. Indeed, Carey and Lydon critique British Empire scholarship on imperial networks for, in their view, paying insufficient attention to Indigenous perspectives.Footnote 60 In the meantime, in their 2015 edited collection Indigenous Communities and Settler Societies, Alan Lester and Zoe Laidlaw ask how to think about Indigenous communities as simultaneously global and local, or indeed as translocal, as they point to the ‘analytical difficulty of encompassing the global scale of Indigenous dispossession and resilience in the face of the Anglo-world’s settler invasion, while simultaneously comprehending the local particularities of these processes in individual Indigenous communities’.Footnote 61 Family histories can scarcely solve all these problems, but they can remind us of entanglements that were often purposely forgotten. They can also at times help us trace more intimate networks between diverse colonized people, as well as between settlers and Indigenous peoples. They can capture how families moved through imperial spaces.Footnote 62 They can help us think about how Indigenous people were global as well as local.

In all this, it is important to remember, as Simon Potter among others has argued, that networks were not frictionless. Rather, they were imperfect vectors of transmission, deeply shaped by power relationships.Footnote 63 Networks need to be interrogated for what they impeded as well as what they enabled, and they need to be understood as part of a larger analysis of power. This parallels ways in which family networks could be dysfunctional and unequal, complicated by unequal access to power and the complexities and fallibilities of human relationships. If families tied the empire together, they did so in a very uneven manner, shaped not only by the deeply unequal access of particular families to power, but also by the vagaries of individual experience. Their power was affected by shifts in the politics of kinship at particular times and places, especially, as I suggested earlier, in the teeth of ideas about supposedly modernizing economies and the growth of democracy.

Beyond scholarship on the empire-wide themes studied and methodologies employed in this book, I also draw on a number of significant works in the complicated histories of the particular places to which my subjects travelled. My great indebtedness to other historians of these places will become apparent throughout the book. Here I want to underscore the extent to which these remain living histories, as settler societies struggle with reconciliation and other responses to difficult pasts.Footnote 64 I also want to stress that there is considerable variation in both the popular historical memory and the scholarly historiography of the diverse frontier areas that I discuss. It perhaps goes without saying that despite the continuities of experience imposed by colonialism, Indigenous peoples in each colony were diverse, as were circumstances of demography and environment. This warns against too readily flattening differences, whatever the global ambition of this project.Footnote 65

It is instructive to compare the politics of memory in Australia and South Africa. Australia has been wracked by debate, the so-called history wars, over the extent of violence towards Indigenous people and appropriate reparations. Even if it took an extensive public debate, the violence of conquest has been reaffirmed in the wake of high-profile controversy in the early years of the twenty-first century sparked by Keith Windschuttle’s claim that ‘black armband’ historians had dramatically inflated the number of deaths in frontier conflict for political ends.Footnote 66 Even here, however, the full extent of violence has been disputed and frequently understated. Lyndall Ryan has published initial results from her team’s attempt to count and to map massacres of Indigenous people on the Australian continent. Even the minimal counts, using a protocol that requires stringent documentation, make it clear that massacre was the ready companion of settlement in Australia, a context in which the British state had made no agreements with the many Indigenous peoples and there were multiple fresh frontiers throughout the nineteenth century. Australian scholarship is certainly not exclusively concerned with violence, but the theme does permeate much historical writing and public discourse.

In South Africa, the genocide of San peoples was followed by two hundred years of further horrors, while Khoekhoe- and San-descended people were for a long time seen as ‘coloured’ people under apartheid (supposedly more privileged than ‘Africans’) rather than as Indigenous people. So far, land reparations have been for post-1913 dispossession, excluding the earlier colonization of the Khoekhoe and San. What does it mean to be Indigenous in Africa and who falls within that category? To be Indigenous on the global stage has given more power to the marginalized San of Botswana, for example; the claim has also excited controversy. South Africans have no difficulty believing in the violence perpetrated against the San, but neither the majority government now nor the apartheid government of the past has emphasized the subject. The situation is completely different again in New Zealand, with its substantial Maori population, where the events of this period are used to inform the decisions of the Waitangi Tribunal.

The past, in other words, continues to haunt the present, just as, of course, the present haunts our reading of the past, but in shifting and contingent ways. This book discusses a historical period when settler colonial states were entrenched, in a manner that made them seem part of an inevitable historical process to many observers by the end of the period, in a way in which they were not at the start. We continue to live with the aftermath of these assumptions, and these experiences.