To the Editor—Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) improves care and reduces costs by allowing patients to complete prolonged therapy at home.Reference Minton, Murray and Meads1 Most pediatric literature related to OPATReference Goldman, Richardson and Newland2 focuses on maximizing intravenous (IV)-to-oral conversion to avoid known catheter-associated complications and antibiotic toxicity. But for cases without oral alternatives, no evidence-based method exists to determine which patients will succeed with OPAT or which social determinants of health (SDOH) drive OPAT outcomes. The current OPAT guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)Reference Norris, Shrestha and Allison3 acknowledge a paucity of evidence; thus, guidance lacking on equitable OPAT use for patients experiencing high social risk. A gap exists in our ability to identify and mitigate the impacts of unconscious bias and systemic racism on OPAT delivery when individual providers must judge which patients are “appropriate” for OPAT.

To examine and learn from the biases inherent in our own pediatric OPAT programs, we describe 2 challenging OPAT cases and propose best practices to identify, evaluate, and address barriers to achieving favorable OPAT outcomes. We identified 2 core questions to examine when considering OPAT: (1) “Is continued hospitalization preferable?” and (2) “What individual SDOH needs must be addressed to support successful OPAT?”

OPAT versus continued hospitalization

Case 1: With first-time parents carrying a remote history of substance use disorder, an infant with bacteremic urinary tract infection was deemed “not appropriate” for OPAT and remained hospitalized for 2 weeks to complete treatment. The provider teams discussed the possibility of OPAT but never broached OPAT with the family. Provider assumptions about the family’s ability to complete OPAT precluded open conversations to understand the family’s support systems, history of drug use, health literacy, and care preferences. The 2004 IDSA guideline and subsequent reference materialsReference Tice, Rehm and Dalovisio4,Reference Shah and Norris5 outlined the basic components of a successful OPAT plan: OPAT is available, caregivers are willing and can be taught, ID providers can communicate with caregivers during the OPAT course, and the patient will return for follow-up appointments. The differential application of these subjective criteria, whether due to provider biases or lack of information, can lead to preconceived judgments and inequitable access to OPAT.

Social determinants of OPAT outcome

Case 2: The infectious diseases attending physician recommended that a child with epidural empyema receive IV ceftriaxone and oral metronidazole for 4–6 weeks. His mother worked full-time at a check-cashing company and the father stayed home; neither parent had attended college. The family lived 4 hours from our medical center with 2 other school-aged children at home. Endorsing financial strain due to rent increases and hesitancy to take unpaid time off work, the parents were eager to learn how to provide care at home. The primary team initially intended to keep the patient admitted, acknowledging both discomfort at transitioning care to parents whose level of education was perceived to be a barrier to infusion teaching and concerns about their home distance from care. However, upon recognition of the adverse financial and job security ramifications for parents, the primary team worked with the infusion trainers to augment teaching for the family. Both parents received infusion training and practiced their new skills with bedside nursing assistance; the patient completed OPAT successfully.

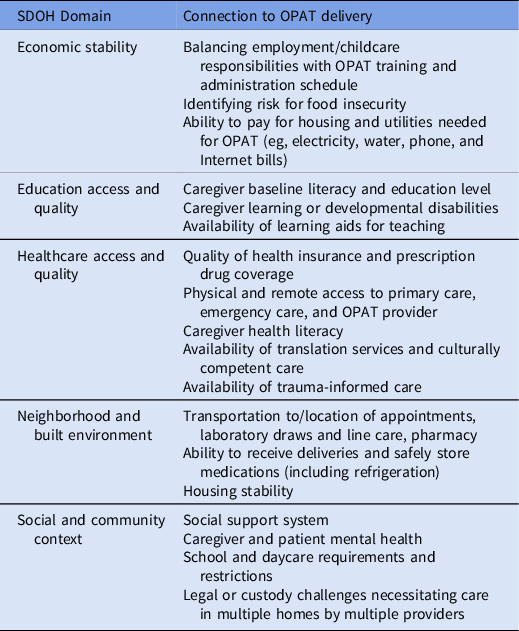

This case description demonstrates that learning family lived experiences can better inform the decision to pursue OPAT and foster its success. Challenges to OPAT success can arise based on various SDOH factors (Table 1).6 These circumstances may require additional resources or creative problem-solving to support families in successfully administering OPAT. Identifying these issues prior to discharge can inform effective mitigation strategies, allow time to secure care coordination resources, and streamline visits for the family.

Table 1. Aspects of OPAT Care in Relation to SDOH Domains

Note. OPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy; SDOH, social determinants of health.

Communication merits special attention. Along with telephone and/or internet access, availability, and use of interpreters, particularly for families speaking uncommon dialects, are critical to OPAT success, especially with anticipatory guidance regarding line care, laboratory sample collection, and contingency planning for possible complications. Provider–caregiver communications may benefit from the intentional use of trauma-informed care techniques, using the “4 Rs”: (1) realize the impact of trauma on patient populations, (2) recognize the signs of trauma, (3) deploy a system to respond to trauma, and (4) resist retraumatization.7

Complex challenges arise when delivering OPAT in a pediatric setting. Framing these challenges within the SDOH context can help providers anticipate and mitigate challenges to OPAT success. To better understand the impact of SDOH, OPAT programs must also build a knowledge base around diversity, equity, and inclusion topics. Programs should consider reviewing institutional resource documents to ensure that equity is achieved and that OPAT criteria are overt rather than unwritten. Absent professional society screening tools specific to OPAT planning and delivery, programs may adapt screening SDOH elements important to OPAT (Table 1).Reference Felder, Jungbauer, Woods and Vaz8 Each OPAT program should identify institutional partners and community resources that connect patients with needed support. Although a social work consultation is a valuable initial step, social workers often cannot address all SDOH challenges. Therefore, programs must engage with other stakeholders, including infusion educators, child life specialists, cultural patient navigators, and/or behavioral health providers to support patients and caregivers in navigating their lived experiences during treatment.

In summary, OPAT providers must change their behavior by investigating bias resulting from a lack of uniform OPAT criteria, and by using SDOH screening to prospectively address barriers. By following these strategies, OPAT providers can progress toward offering care that is equitable, accessible, and successful for all patients and families willing to pursue it.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge that they are living and working on the land of the Coastal Salish and Klamath peoples and would like to thank the original caretakers of this land.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.