In the past decade, legislation introducing corporate board gender quotas (CBQs) has spread throughout Europe.Footnote 1 The CBQs have been contested on several grounds, and opposition has been particularly salient among the business elite, emphasizing autonomy of the business owners to freely choose board members and opposition to state intervention (see Chandler Reference Chandler2016; Lépinard and Marin Reference Lépinard and Marin2018; Skjeie and Teigen Reference Skjeie and Teigen2003; Teigen Reference Teigen, Hagelund and Engelstad2015; Tienari et al. Reference Tienari, Holgersson, Meriläinen and Höök2009). Opinions about gender quota regulations are strongly interrelated to larger ideological fronts concerning individual rights, equal treatment, fairness, and justice, and therefore, arguably, are considered fixed and unmovable. But how strong are opinions opposing CBQs? Is it possible to change even elite opinions on these matters? If so, the implications for future policy development and implementation in the gender-equality policy field could be profound.

Studies across social science fields have shown that selecting, highlighting, or emphasizing certain aspects of an issue, often referred to as framing, influences peoples' opinions (e.g., Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a; Scheufele and Iyengar Reference Scheufele, Iyengar, Kenski and Jamieson2017). However, the perspective in most of these studies is that elites, in tandem with the media, influence public opinion by deciding on the frame of issues or events (see, e.g., Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007b; Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2015; Zaller Reference Zaller1992). The extent to which elites are also susceptible to the framing of issues is more of a moot point. The general consensus seems to be that elites are more resistant, as their predispositions are stronger and more consistent than those of the general public (e.g., Zaller Reference Zaller1992). These studies typically rely on population-based surveys; few, if any, studies have empirically investigated framing effects on national elites.

In this study, we explored the extent to which a positive framing of CBQs influences elite opinions on the topic. We utilized a survey experiment embedded in a unique, comprehensive survey of top Norwegian elites: the 2015 Norwegian Leadership Study. The sample population consisted of 1,351 individuals occupying top positions across 10 sectors of Norwegian society. We studied the effect of frames emphasizing information about the prevailing male dominance among the business elite, combined with information about the success of CBQs in promoting gender balance on corporate boards. We studied the effect of framing on two types of dependent variables. The first is support for CBQs. In debates on CBQs, a main claim has been that such policy would also have wider so-called “ripple” effects, increasing gender balance in the business elite in general. We therefore also sought to determine whether positive CBQs framing influences the extent to which CBQs are considered necessary to promote gender balance in business life in general.

The results indicate that elites are indeed susceptible to framed information about gender quotas. Moreover, and contrary to expectations, effects are generally stronger in the business elite than in other elite groups. First and foremost, effects occur in relation to general CBQ support. More modest effects are evident in opinions regarding CBQs being necessary to promote gender balance in business life. These results indicate that elite opinions are not as strong and consistent as one might expect, given earlier research on predispositions as well as public debates on CBQs. Many in the top national elite are susceptible to changing their opinions based on information highlighting the positive effects of quota schemes on the gender composition of corporate boards. In conclusion, we argue that this expands the space for maneuvering for policy makers working on the formulation and implementation of gender-equality measures. Moreover, knowledge about possibilities to increase support for gender equality measures, in countries where CBQs are in effect, is essential because it can prevent backlash. This article contributes to both the scholarly debates on gender quotas and the body of knowledge on framing effects.

GENDER QUOTAS

Gender quotas are often regarded as a controversial means of regulating the gender composition of decision-making positions (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Pamela and Lena2017; Piscopo and Muntean Reference Piscopo and Muntean2018). Such measures have been most widespread in political structures. Within the last couple of decades, electoral quotas have spread worldwide; currently, half of the countries of the world use some kind of electoral quotas for their parliaments.Footnote 2 Quotas in politics are widely considered a “fast track” to gender balance (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2008; Dahlerup and Freidenvall Reference Dahlerup and Freidenvall2005; Krook Reference Krook2009).Footnote 3 However, gender quotas not only have spread across countries but also from the political to the economic field. The CBQs even extend the scope of gender-equality policies by targeting privately owned businesses, and CBQs are generally considered even more contested than political quotas (cf. Chandler Reference Chandler2016; Piscopo and Muntean Reference Piscopo and Muntean2018). This trend relates to the institutional context, where legislatures are expected to reflect the people, and descriptive representations of gender therefore signal representativeness. However, corporations have consumers who primarily care about the goods purchased and less with how the corporate board is composed (Piscopo and Muntean Reference Piscopo and Muntean2018; Teigen Reference Teigen, Engelstad, Holst and Aakvaag2018b). Still, an emerging concern with corporate social responsibility connects gender balance to company interests, either narrowly understood as the effect of gender balance to increase profit and reduce loss or understood within a wider frame of gender balance as an aspect of corporate social responsibility (Terjesen and Sealy Reference Terjesen and Sealy2016).

Although CBQs move beyond the Right-based language of political participation generating strong controversies over these measures, CBQs and political quotas are typically opposed by a notably similar set of standard arguments. Political quotas are argued to violate equality and for being unmeritocratic, undemocratic, and demeaning to women (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Pamela and Lena2017). Similarly, CBQs are often considered to violate equality, being unmeritocratic, at stake with shareholder democracy, and demeaning to women (Seierstad, Gabaldon, and Mensi-Klarbach Reference Seierstad, Gabaldon and Mensi-Klarbach2017; Teigen Reference Teigen, Fagan, Menéndez and Silvia Gómez Ansón2012a; Tienari et al. Reference Tienari, Holgersson, Meriläinen and Höök2009).

The opposition against CBQs has been particularly strong among business leaders in all countries where CBQs have been debated (Axelsdóttir and Einarsdóttir Reference Axelsdóttir and Einarsdóttir2016; Chandler Reference Chandler2016; Menéndez González and Martínez González Reference Menéndez González, González, Fagan, Menéndez and Ansón2012; Lépinard Reference Lépinard, Lépinard and Marin2018; Teigen Reference Teigen, Hagelund and Engelstad2015; Tienari et al. Reference Tienari, Holgersson, Meriläinen and Höök2009). In most countries, representatives from the business sector have participated in the debate as the most outspoken opponents of CBQs. In the following section, we discuss whether elite support for CBQs might nevertheless be swayed by how the issue is framed.

FRAMES AND FRAMING EFFECTS

In public debate and the news media, a political problem, an issue, or an event is never covered from all angles. Some aspects are always selected and highlighted, this is referred to as frames and framing (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a; Entman Reference Entman1993; Scheufele and Iyengar Reference Scheufele, Iyengar, Kenski and Jamieson2017; Verloo Reference Verloo2005). Frames typically select and highlight some aspects of an event, define the problem, argue for causes, make judgments, and/or suggest remedies (Entman Reference Entman1993, 52). In gender studies, frames and the importance of how political problems are represented have been a central area of research in recent years (e.g., Bacchi Reference Bacchi, Lombardo, Meier and Verloo2009; Lombardo, Meier, and Verloo Reference Lombardo, Meier and Verloo2009; Verloo Reference Verloo2005). For example, gender quotas could be framed as discrimination or antidiscrimination, discrimination or the special contribution of women in male-dominated fields, or “helping” women or measures against the overrepresentation of men. These are examples of struggles over where to place “the burden of proof”—those defending status quo or those advocating equality (Bacchi Reference Bacchi, Lombardo, Meier and Verloo2009; Murray Reference Murray2014; Teigen Reference Teigen2000). In public debate, although one frame might be dominant, several “competing” frames might exist as different actors try to dominate public debate with their particular frame (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2013; Disch Reference Disch2011).

Based on this description of the debates on the introduction of CBQs, the dominant frames in most countries have arguably been male dominance among the business elite versus the autonomy of business owners to freely choose their board members. In the following section, we discuss how such frames are likely to influence peoples' opinions.

Attitude and Opinion Change—Framing Effects

The specific framing of an issue or event also affects peoples' opinions on the issue (see Iyengar Reference Iyengar1991; Scheufele and Iyengar Reference Scheufele, Iyengar, Kenski and Jamieson2017; Zaller Reference Zaller1992). Frames define the packaging of a problem, an issue, or event in a way that encourages certain interpretations and discourages others. This perspective is rooted in the so-called conventional expectancy model developed within research on attitudes and attitude change (e.g., Ajzen and Fishbein Reference Ajzen and Fishbein1980). In this influential model, an attitude toward an object is thought of as the weighted sum of a series of beliefs (or considerations) about the object (see Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a for a discussion related to framing).Footnote 4 Considering attitudes toward gender quotas as an example, an attitude can be the result of considerations related to the level of gender equality in society, in general, and in the business sector, in particular, but it can also include considerations related to rights connected to ownership, state intervention, etc.

The idea behind framing effects is that when the presentations of an issue emphasize one aspect of that issue or event, the corresponding consideration by the audience will become more salient or will be given more weight than other considerations.Footnote 5 Such framing effects on attitudes are supported by numerous studies from several disciplines and fields. The study by Tversky and Kahneman (Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981) showed the manner in which peoples' choices are influenced by the framing of a problem, even when the information presentation is identical, which is referred to as “equivalency frames.” “Emphasis frames” offer “qualitatively different yet potentially relevant considerations” that individuals use to make judgments (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a, 114). A common example is that people are much more inclined to accept a Ku Klux Klan rally when the news report is framed in terms of free speech than when it is framed in terms of public safety concerns (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rosalee and Zoe1997). Such framing effects are found in numerous studies, for instance, in regard to framing deservingness to win support for welfare state retrenchment (Slothuus Reference Slothuus2007), and more recently, when different welfare reform pressure frames makes people more worried about the welfare state (Goerres, Karlsen, and Kumlin Reference Goerres, Karlsen and Kumlin2018).

At the outset, therefore, we expect that people are influenced by how CBQs are framed and that referring to the success of CBQs in achieving gender balance in the male-dominated business sector will make elites more positive toward the scheme. But are elites a special breed that is next to impossible to influence? Theories and models of framing and attitude change are mostly about changes in the opinion of the general public. Indeed, as mentioned earlier, most of the extensive literature on framing explicitly treats the phenomenon as elite frames influencing public opinion. Few, if any, of these studies investigate whether elites themselves are susceptible to framing. Most studies of opinion and opinion change distinguish between people based on education, income, and/or political awareness. The general consensus from these studies seems to be that it is difficult to influence elites (meaning the highly educated, high income, and political aware) because they have stronger and more consistent predispositions (Zaller Reference Zaller1992). Strong predispositions reduce framing effects because they increase resistance to disconfirming information (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a, 111). Ever since Converse's (Reference Converse and Apter1964) seminal study, social elites have been found to have stronger, more coherent, and stable attitudes. Still, even people with strong predispositions are susceptible to framing, particularly in relation to new issues, and recent research suggests that framing at least influences the attention of the political elite (Walgrave et al. Reference Walgrave, Sevenans, van Camp and Loewen2018). As for knowledge about the issue, the evidence is mixed. Some studies point to it being more difficult to influence people with a high level of knowledge, whereas other studies report the contrary (see Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007a for an overview).

On the basis of existing research, although elites are considered to have stronger predispositions than the general public, the evidence suggests that a positive CBQs frame will increase support for CBQs (Hypothesis 1a) and that a positive CBQs frame will increase adherence to the opinion that CBQs are necessary to achieve gender equality among the business elite (Hypothesis 1b).

Elites have stronger predispositions, and we expect the effects of framing to be rather small. Following the same logic, we are also able to formulate expectations related to gender and elite groups. It should be more difficult to influence elites with particular interest or knowledge about CBQs because they most likely have stronger and more consistent predispositions on the issue. Nevertheless, it is difficult to hypothesize gender differences in a unidirectional manner. On one hand, gender quotas are closer to home for women than men; thus, they might be more influenced than men when they hear about male dominance and the success of CBQs. We therefore expect that framing effects will be stronger for women than for men (Hypothesis 2). On the other hand, gender equality issues and gender quotas are most likely more salient for elite women than for elite men. Many, if not most, men have probably spent less time thinking about gender issues than women. Consequently, they may have weaker predispositions and may be more susceptible to information and framing. Indeed, Clayton, O'Brien, and Piscopo's (Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2018) study of “all-male panels” suggests that information about women's presence on decision-making bodies sends stronger signals to men than to women when it comes to considering decisions legitimate. Thus, for gender, we also formulate the opposite expectation: framing effects will be stronger for men than for women (Hypothesis 3).

The differing effects between elite-group expectations are more easily hypothesized based on proximity and knowledge. CBQs affect business elites to a greater extent than other elite groups, as the jurisdiction is directly related to their sector. Moreover, as they live and breathe in the sector, the treatment should be more salient for this elite group than for other groups. We therefore expect that the business elite will be more resistant to information about male dominance and the success of gender quotas than other elite groups (Hypothesis 4).

THE NORWEGIAN CONTEXT: DEBATE ON CORPORATE BOARD QUOTAS

In 2003, as the first country in the world, the Norwegian parliament adopted a regulation demanding the representation of at least 40% of each gender on the boards of state-owned, intermunicipal, and public limited companies (PLCs).Footnote 6 Similar regulations have been adopted in a range of countries including Spain, Iceland, France, Belgium, Germany, Portugal, and Austria (Fagan, González Menéndez, and Gómez Ansón Reference Fagan, Menéndez and Silvia Gómez Ansón2012; Lépinard and Marin Reference Lépinard and Marin2018; Piscopo and Muntean Reference Piscopo and Muntean2018; Seierstad Gabaldon, and Mensi-Klarbach Reference Seierstad, Gabaldon and Mensi-Klarbach2017; Teigen Reference Teigen, Engelstad and Teigen2012b; Terjesen, Aguilera, and Lorenz Reference Terjesen, Aguilera and Lorenz2015).

The CBQ regulation was set out in the Norwegian Public Limited Liability Companies Act in Articles 6–11a for PLCs, with parallel formulations in other parts of company legislation regarding state-owned companies. The rules regarding the representation of both sexes are to be applied separately to employee-elected and shareholder-elected representatives to ensure independent election processes.Footnote 7 The CBQs were expanded to include cooperative companies in 2008 and municipal companies in 2009. The boards of the numerous but often small- and medium-sized LTDsFootnote 8 are not subject to such regulations.Footnote 9

For state-owned companies and intermunicipal companies, the regulation adopted in 2003 was effectuated in 2004. For PLCs, the regulation adopted in 2003 was formulated as “threat” legislation: Had PLCs not voluntarily met the requirement for gender composition by July 2005, the regulation would have been effectuated. Although female representation increased between 2003 and 2005, the target of 40% of women was not reached for the boards of the PLCs. Thus, in December 2005, the government decided to effectuate a CBQ regulation for the boards of start-up PLCs from 2006 and for all PLCs from 2008. The 40% target was met, and the regulation was fully implemented in 2008. The rather tough sanctions attached to the legislation probably contributed to its successful implementation. The Companies Act applies identical sanctions for breach of all its rules, with forced dissolution being the final step for companies violating the regulations of this act. The Norwegian register of business enterprises established to ensure compliance with the law reports on companies to ensure compliance.

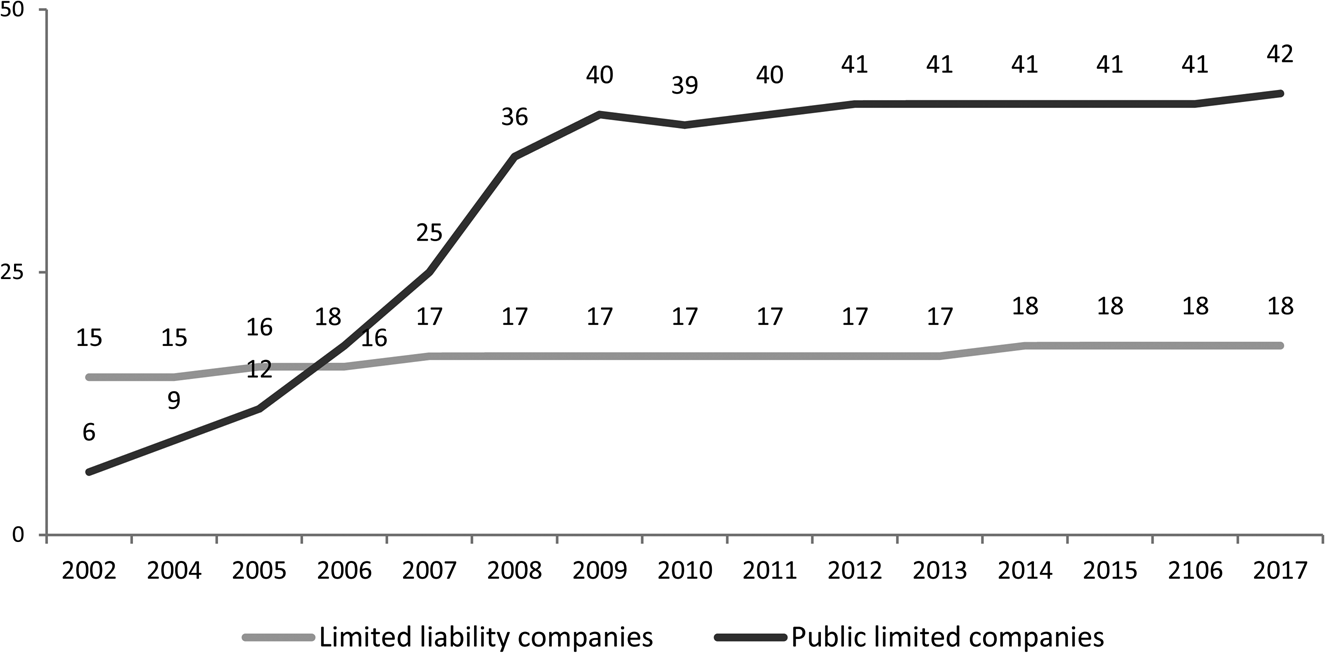

In Figure 1, the black line shows the change in the proportion of women on the boards of PLCs, and the grey line illustrates the proportion of women on the boards of LTDs, which are not subject to CBQs. The representation of women on PLC boards increased quickly after the “threat” legislation (2003–2005) became actual legislation (2005) and continued to rise until full implementation (2008). However, the figures indicate that the quota legislation had no ripple effects on the company boards of LTDs.

Figure 1. Proportion of women on the boards of public limited companies (PLCs) and limited companies (LTDs), Norway, 2002–2017.

The CBQ debate has mainly revolved around PLCs because state interference in the board composition of companies where ownership is traded on the market is generally understood to violate the autonomy of the business sector (Teigen Reference Teigen, Hagelund and Engelstad2015). Prior to the introduction of CBQs, the debate in Norway focused on ownership rights, shareholders' democracy, equal treatment, and whether there would be enough qualified women around (Teigen Reference Teigen, Lépinard and Marin2018a). In addition, CBQs as demeaning to women appeared in the debate, but it was not central. Rather, it was argued that women would not become full board members but would be excluded from the “inner circle” of the board (Storvik and Gulbrandsen Reference Storvik and Gulbrandsen2016).

The Norwegian context therefore offers the opportunity to study framing effects in a setting where the implementation of CBQs was highly controversial but achieved its main and direct objective of gender balance quite rapidly.

DATA AND DESIGN

The experiment is embedded in a comprehensive survey of Norwegian elites: the 2015 Leadership Study (see Torsteinsen Reference Torsteinsen2017). The elite survey sample was constructed using the so-called “position” method (Hoffmann-Lange Reference Hoffmann-Lange, Dalton and Klingemann2007). The 1,939 individuals who occupied the most important leadership positions in Norwegian society were included in the initial sample. Ten distinct societal sectors were chosen: research/education, the church, culture, the media, business, organizations, police and judiciary, politics, the state administration, and the military. The fieldwork was carried out by Statistics Norway. The interviews were conducted by telephone and personal interviews, with a response rate of 72%, leaving 1,351 elite respondents.

Design, Treatment, and Dependent Variables

The research design followed a classic experimental approach, in which one experimental group received the treatment and the control group did not. The treatment was formulated based on the framing framework, emphasizing both the definition of the problem (male dominance in business) and a solution (CBQs). The treatment group was exposed to an introductory text with information about continuous male dominance in the business sector and the success of the quota scheme in resulting in 40% of women on the corporate boards of listed companies:

Norwegian business life is highly male dominated. Today, there are almost no women among the corporate leaders of the largest companies, but as a result of gender quotas, there are 40% women on the boards of listed companies.

This treatment represents a genuine one-sided frame because the “necessity” and success of the quota scheme were emphasized.

We investigated the effect of the treatment on two dependent variables. First, we investigated general support for CBQs. More specifically, the first dependent variable was formulated as follows:

There are several schemes that aim to equalize gender differences regarding participation in various areas of society:

Are you for or against that gender balance on the boards of listed companies should be at least 40% of the underrepresented gender?

The answer categories were a simple dichotomy: for or against.

We then sought to determine whether the treatment would affect opinions about whether CBQs were necessary in achieving gender balance among the business elite more generally. Our second dependent variable was formulated as follows:

There are differing views on whether gender quotas on corporate boards are necessary to promote gender balance in Norwegian business life. Using the scale on the card, where 0 means that gender quotas are necessary and 10 means that gender quotas are unnecessary, where would you place yourself?

In the analysis we recoded the scale so that high value (i.e., 10) indicates ‘necessary.’

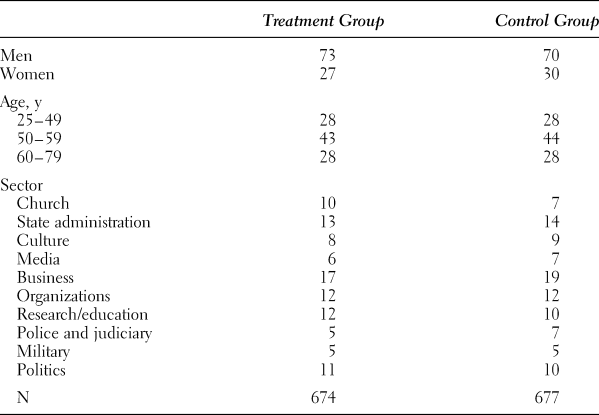

The total elite sample was divided into a treatment group and a control group of equal size. Table 1 presents the distribution of the treatment group and the control group in terms of essential factors that might influence opinions toward CBQs (i.e., gender, age, and sector). Only minor differences relating to gender and age were observed. In terms of sector, the church was underrepresented in the control group; however, the differences were minor.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the treatment and control groups

RESULTS

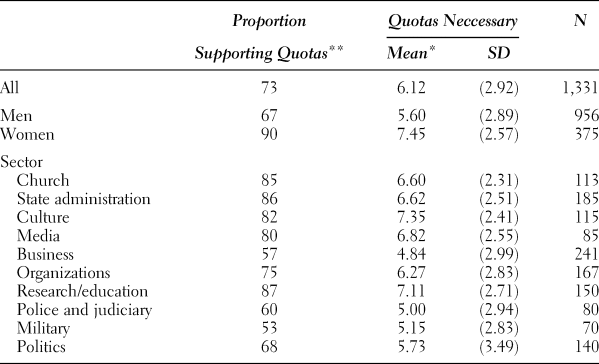

First, to get an impression of elites' overall opinions regarding CBQs, we present the distribution of the two dependent variables for the total sample, both overall and by gender and elite group (Table 2). Overall, 73% were in favor of CBQs: the gender balance on the boards of listed companies should be at least 40%. The overall mean for gender quotas being necessary to promote gender balance in business life was clearly on the necessary side of the scale at 6.12 (i.e., 0–10, 5 being the center). However, there were clear differences for both questions based on gender and sector.

Table 2. Distributions of the two dependent variables for the total sample

** Proportion in support of at least 40% of each gender on the boards of listed companies.

* Mean on a scale from 0 (not necessary) to 10 (necessary).

SD, standard deviation.

Of 10 women among the Norwegian elite, nine supported CBQs. Although the number was lower for men, a clear majority of 67% supported CBQs. The gender difference was also large in terms of whether CBQs were seen as necessary to achieve gender equality, but the mean, even for men, leaned toward “necessary.” Business elites, together with the police and judiciary, and the military elites, were less supportive of CBQs than other elites.

The question, then, is the extent to which the treatment presented above influenced elite opinions on these matters. We investigated the two dependent variables separately. First, we studied the effect of the treatment on the general support for CBQs on the boards of listed companies.

General Support for CBQs

To study the effect of the treatment, we used linear probability models.Footnote 10 In the model, the constant can be interpreted as the proportion supporting CBQs in the control group, and the b-coefficient indicates the difference between the control and treatment groups.

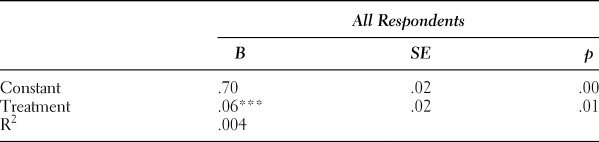

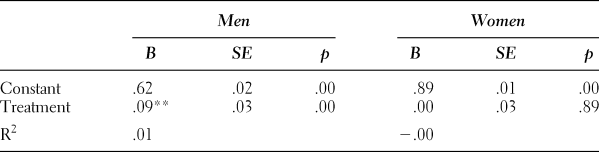

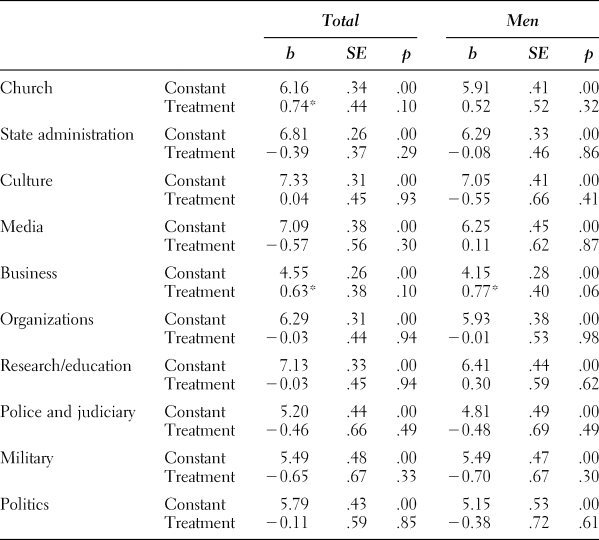

The results presented in Table 3 clearly support the expectation that positive framing of CBQs affects support for CBQs (Hypothesis 1). The treatment group was significantly more likely to support CBQs. The effect of the treatment was 6 pp, which is clearly significant (p < 0.01) and indicates that 20% (six of 30) of the elites opposing CBQs were affected.

Table 3. Linear probability model of the effect of the treatment on support for CBQs

Dependent variable: 1 = “support present quota scheme”; 0 = “against the current quota scheme.”

N = 1,330.

CBQs, SE, standard error.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; * p < 0.10.

Above, we discussed that it is possible to make the case that both elite women and men would be influenced by the treatment. Perhaps a bit surprisingly, however, the effect of the treatment was only found among men. Table 4 shows that the men in the treatment group had a significantly higher chance of supporting the quota scheme. Only six of 10 men in the control group supported CBQs. However, when presented with the positive information, 24% (nine of 39) were affected, and in the treatment group, seven of 10 supported CBQs. This is quite a substantial effect, and it is clearly significant. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported. As shown in Table 2, women were much more likely to support CBQs than men. Also, 90% of women in both the control and treatment groups supported CBQs. Thus, few women were left to persuade.

Table 4. Linear probability model of the effect of the treatment on support for CBQs (by gender)

Dependent variable: 1 = Support present quota scheme.

N (men) = 955; N (women) = 374.

CBQs, SE, standard error.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05. *p < 0.10.

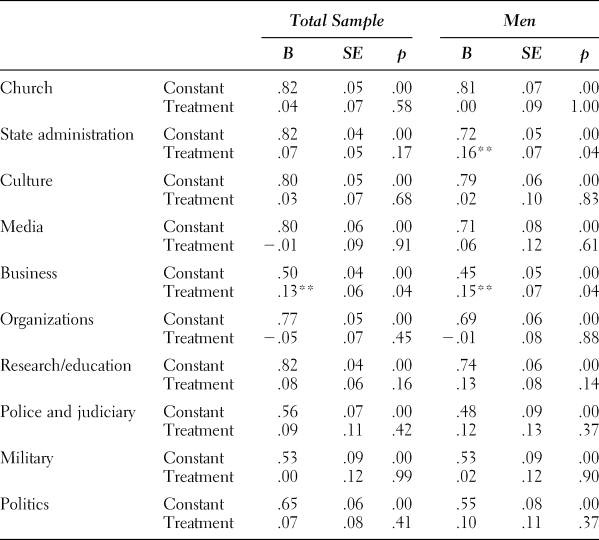

Table 5 shows the effect of the treatment among different elite groups. We expected the business elite to be particularly resistant to the treatment due to proximity and knowledge about the issue at hand (Hypothesis 4); however, we found the opposite result. Effects were generally stronger among the business elite than among other elite groups. Here, the difference between the control group and the treatment group was 13 pp (b-coefficient), which is a substantially large effect. Thus, once again, the results are the opposite of what we expected from resistance due to proximity to the policy area. Moreover, when we ran the model for men only, the effects were even stronger. The difference between the control group and the treatment group was 15 pp (b-coefficient).Footnote 11

Table 5. Linear probability model of the effect of the treatment on support for CBQs by sector

The models were run for the total sample and for men only.

Dependent variable: 1 = support present quota scheme.

CBQs, SE, standard error.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.10.

Effect of CBQs as Necessary to Promote Gender Balance in Business Life

In this section, we analyze the effect on the second dependent variable: opinions on the extent to which CBQs are necessary to promote gender balance in business life in general. Our main hypothesis was that when exposed to positive framing, elites would become more supportive of this statement (Hypothesis 1b).

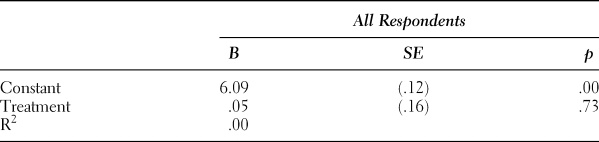

Table 6 reports on the overall effect of the treatment and does not support the expectation that the treatment will increase adherence to the belief that CBQs are necessary to promote gender balance in the business sector. We found no significant difference between the treatment and control groups. Thus, Hypothesis 1b was not supported. The intercept indicates the mean for the control group. The difference between the control group and the treatment group only constitutes 5% of one scale point on the scale from zero to 10 and should be considered negligible. Table 7 presents the results when we ran the model separately for men and women.

Table 6. OLS regression of the effect of the treatment on CBQs as necessary to promote gender balance

N = 1,347.

Dependent variable: 0–10.

OLS, ordinary least squares; CBQs, SE, standard error.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.10.

Table 7. OLS regression of the effect of the treatment on CBQs as necessary to promote gender balance (by gender)

N (men) = 955; N (women) = 374.

Dependent variable: 0–10.

OLS, ordinary least squares; CBQs, SE, standard error.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.10.

As illustrated in Table 2, women were much more inclined than men to believe that CBQs are necessary to promote gender balance in business life in general. However, this difference was not due to women being more influenced by the treatment than men. Again, there were no significant differences between the treatment and control groups, and neither Hypothesis 2 nor Hypothesis 3 was supported in this case.

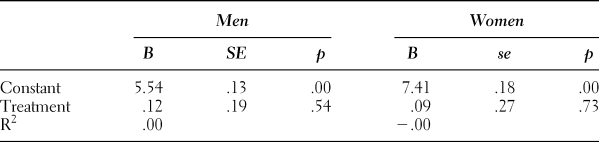

However, the treatment seemed to affect certain elite sectors (Table 8). Our expectation was that the business elite would be less affected by the treatment than other elite groups due to their proximity to the issue at hand. Contrary to these expectations, the effects were generally stronger among the business elite than in other elite groups. The difference between the treatment and control groups was quite large and significant at the 10% level for the business elite. As shown at the outset in Table 2, the business elite were the most negative toward the notion that CBQs are necessary to promote gender balance among their rank. The difference between the control and treatment groups was 0.6, indicating that the business elite in the control group were highly negative; however, the treatment enabled the business elite to move toward other elites. Again, the effects were even stronger when only men were included in the analysis. However, the mean derived from business elites who were exposed to the treatment (5.18) was still lower than the means in all other elite groups.

Table 8. OLS regression of the effect of the treatment on CBQs as necessary to promote gender balance (by elite sector)

Dependent variable: 0–10.

OLS, ordinary least squares; CBQs, SE, standard error.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.10.

DISCUSSION

Gender quotas, and CBQs in particular, have been met with severe opposition. In this article, we have shown that such opposing opinions can be influenced by a positive frame. Elites have been thought to be more resistant to framing, and their predispositions have been found to be stronger and more consistent than those of the general public (e.g., Zaller Reference Zaller1992). However, few, if any, studies have empirically investigated framing effects on national elites. In this article, we sought to determine whether national elites, the people occupying the top echelons across 10 sectors in Norwegian society, are susceptible to positive framing of CBQs. The results clearly indicate that they are. When exposed to information about prevailing male dominance among the business elite and the success of CBQs in achieving gender balance on corporate boards, the elites were significantly more likely to support gender quotas. The effect was quite substantial: one in five was influenced by the treatment. The effect was primarily found among men, the 10% of women who opposed CBQs were not easily persuaded. Interestingly, and contrary to expectations, the effect was strongest for men in the business elite.Footnote 12

Framing had a more modest effect on the second dependent variable: if CBQs are necessary to promote gender balance in business life in general. Overall, there was no difference between the control and treatment groups. The treatment did not contain any information about such ripple effects, and indeed, empirical studies indicate that reports of such effects are scarce (see Bertrand et al. Reference Bertrand, Black, Jensen and Lleras-Muney2014; Halrynjo, Teigen, and Nadim Reference Halrynjo, Teigen, Nadim and Teigen2015),Footnote 13 so it is no surprise that effects of the treatment are weaker on this variable. However, again, men in the business elite were influenced.

Opposition to CBQs has been most strongly expressed by business actors (Chandler Reference Chandler2016; Skjeie and Teigen Reference Skjeie and Teigen2003). As such, the finding that the effects were generally stronger among the business elite was surprising, and the contrary of what we expected. As the CBQs jurisdiction concerns their sector, we expected the issue to be most salient for the business elite compared to other elites and that they would have more in-depth knowledge about the issue, resulting in strong predispositions. In what follows, we formulate three arguments to help explain this result.

First, although challenges relating to gender equality are particularly pronounced in the business sector, it might not necessarily mean that the awareness of the situation within business is particularly high or that the salience of the issue is exceedingly high. The relatively low level of support for CBQs among the business elite does suggest that other frames that are perhaps more typical in a business setting, such as nonstate intervention and ownership rights, are the more easily accessible frames for this group. The results nevertheless suggest that these general frames can take the backseat to gender equality frames when presented with specific information about the issue. However, the only restriction CBQs lays on ownership rights is that candidates have to be selected from the whole population, not exclusively the one-half consisting only of men. Hence, CBQs are not necessarily at odds with owners' autonomy, and it could be possible to integrate support for CBQs with these types of considerations.Footnote 14

Second, and highly related to the first point, although opposition to CBQs was voiced by business elites in the media, the dominant elite frames documented in much earlier research, were not generated by an entire group of elites but more likely by a subgroup of especially engaged people, key stakeholders acting as (elite) opinion leaders on this subject. Although these particularly engaged segments of the elite will be resistant to framing, as they most likely have strong predispositions on the issue, other less engaged segments might be less resistant. Moreover, although studies of elites and social class have started to examine political attitudes in their research agenda (e.g., Flemmen Reference Flemmen2014), little is known about differences in the individual ideological consistency between elite groups. One possibility is that business elites have less ideologically coherent attitudes than other elite groups and are, therefore, more susceptible to framing. This should be an interesting avenue for future research.

Third, because the opposition to CBQs is strongest within the business sector, the potential for change is arguably also greatest in that group. Thus, a research design that also included a negative frame would therefore have been more balanced. Although a research design with two treatment groups would have worked for the entire elite sample, it would have prevented the testing of differences between elite groups, as the sample size (N) would have been too small. Hence, a balanced design would have come at the expense of the study of effects within the business elite.

In the literature and public debates, opinions on gender quotas are linked to larger ideological fronts concerning individual rights, equal treatment, fairness, and justice. From this perspective, opinions can give the impression of fixed or frozen cleavages. However, the results of this study show that attitudes toward CBQs are influenced by the framing of the issue and that opinions are easier to defrost than perhaps often believed. Even though this experiment, like all experiments, has problems with external validity, like the enduring effect of framing (e.g., Lecheler and de Vreese Reference Lecheler and de Vreese2011), the results suggest that the frames that dominate a public debate can sway elite opinions.

CONCLUSION

We have investigated opinions toward CBQs in one context: a country with continuous male dominance in business life, but with successfully implemented CBQs. The results from this context are important for the body of work on gender and politics for at least two reasons: Continuous support for an implemented policy is essential to prevent backlash and dismantling of policies. Elite opinion change about CBQs due to positive framing is therefore essential knowledge. Moreover, it is possible to change opinions even in the Norwegian context where CBQs were highly debated prior to implementation, which suggests that is possible to do so also in other types of contexts. However, to increase our knowledge about elite opinion change on gender-equality policy issues, studies that investigate attitude change to quota policies that is not yet in place are needed, as are studies investigating CBQs opinion change in contexts where CBQs are not adopted. Such studies would offer clues about the scope conditions for influencing elite opinions on gender policy issues.

The results in this article have potentially serious implications for the formulation of public policy. They support results from studies on the international diffusion of political quotas that indicate that the way in which gender issues are framed and the particular political constellations at the time have a strong impact on whether gender quotas are adopted or not (Krook Reference Krook2009, 218–222). These earlier studies did not, however, investigate whether elites themselves are influenced by how the issue is framed. Our study indicates that even relevant elite stakeholders are affected by the framing of issues and suggests that policymakers might consider opposition to policy issues, even among national elites, as something it is possible to influence and change.

APPENDIX

Table A1. Original and English translation of the treatment text

Table A2. Original and the English translation of the dependent variables