A political scientist conducting interviews on wartime sexual violence finds herself at a health clinic being introduced to patients who are obviously younger than 18. A team of researchers running a behavioral experiment wonders if its local partner organization is endangering participants to randomize treatment in its conflict-adjacent villages. A graduate student working on a shoestring budget in a refugee camp is relieved to find an educated, passionate research assistant (RA) who is eager for work experience and will set up, conduct, translate, and transcribe politically sensitive interviews for only $60 a month.

All of these academics are benefiting from the unparalleled access to research subjects, local partners, and labor that often are present in environments of extreme state fragility or conflict. As the volume of field-based research in such contexts increases, it is difficult to ignore the fact that these settings pose challenges not present elsewhere. In countless discussions at conferences, in graduate-student seminars, and in the field, we have heard fellow social scientists echo a common theme regarding research in these contexts: concerns about the ethical implications of their fieldwork and uncertainty about how to mitigate them.Footnote 1 Nearly every researcher we spoke with described at least one instance in which they were called on to make an on-the-spot decision involving ethical issues that they had not anticipated, without time to fully consider the consequences. On subsequent reflection, they often wished they had made different decisions.

This article explores the ethical pitfalls presented by conflict field research by drawing on our own experiences and those of our colleagues.Footnote 2 Following a brief discussion of some common features of these settings, we explain how fragility and conflict can generate ethical dilemmas involving research subjects and partners not present elsewhere. We conclude with a set of practical questions and recommendations for those undertaking fieldwork in areas of state fragility or violence, as well as for those evaluating, advising, and reviewing such work.

FIELDWORK IN VIOLENT OR FRAGILE SETTINGS

Stepping off the plane at a field site in Western Europe, a researcher can feel confident that with an approval from her home institution’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), certification from the host-country’s national ethics committee, and perhaps a prearranged partnership agreement with a local organization, she is clear to begin her research. Arriving in an environment of state fragility or violent conflict can be a different story.

IRBs assume regulatory structures and sociopolitical norms that quickly lose relevance outside of Europe and North America. Governments in fragile and violent contexts may have agencies in the capital that are dedicated to issuing formal research permissions. However, in practice, research sites might fall under the control of fragmented bureaucracies, non-state armed actors, customary authorities, NGOs, civil-society groups, international agencies, or UN Missions. Contested territorial control may mean that researchers must obtain formal permissions from parallel authority structures to avoid risks to their personal security.Footnote 3

Areas characterized by these dynamics pose a series of unique challenges. Various stakeholders may levy formal and informal fees for research permissions, access to public records, and access to territory. Which fees constitute legitimate research expenses and which constitute forms of graft are rarely clear cut. Furthermore, it may be impossible to (safely) travel through or conduct research in certain areas without paperwork authorized by an insurgent organization. However, paying the administrative fees demanded qualifies as “supporting a rebellion” in the eyes of the territorial state (as well as perhaps the US Government’s Office of Foreign Assets Control).

Finally, deference to the central government—a given in many settings—may be a questionable choice when that government lacks control over the research context, is openly hostile to certain populations or human rights concerns, or shuns academic researchers. In repressive states, whether to comply with government visa requirements or obtain ethics approvals from host governments poses a serious dilemma for many academics who may need to obscure the purpose of their travel to avoid surveillance, harassment, or worse.Footnote 4 When invited to attend a human rights conference in a country that had recently initiated a crackdown on civil society and that frowned on external human rights researchers entering the country, Cronin-Furman’s attempts to secure the appropriate travel documents descended into Kafkaesque absurdity. The country’s consular officials in the United States ultimately suggested traveling on a tourist visa, with “fingers crossed” against deportation for engaging in unlawful human rights–related activities. This example highlights the fact that when regulatory processes are unclear, contradictory, or morally questionable, what constitutes ethical research practice often is debatable. Furthermore, following guidelines that determine ethical behavior at home can place research subjects at immense risk. For example, researchers frequently cite concerns about IRB demands for written consent. In the context of political insurgencies or civil-society crackdowns, even electronic documentation of field notes can pose grave threats to interviewees (Koopman Reference Koopman2017; Parkinson Reference Parkinson2015).

Furthermore, following guidelines that determine ethical behavior at home can place research subjects at immense risk. For example, researchers frequently cite concerns about IRB demands for written consent.

Security challenges are often exacerbated in volatile research environments, where evolving security dynamics make continual reassessment necessary. A month after a colleague arrived in Iraqi Kurdistan in May 2014, a quiet and stable field site became rife with uncertainty. Facing the rapid approach of ISIS, his informants assured him that they were still available to go forward with scheduled interviews; he was unsure whether to take them at their word. Were they neglecting their own safety to accommodate him, or were they simply more knowledgeable about the level of threat? Whereas American and European academics are often able to mobilize foreign passports or take advantage of humanitarian networks to evacuate rapidly if a security situation deteriorates, local interlocutors rarely can. Moreover, the growing tendency for researchers to drop in and out of insecure field sites without extensive knowledge of local politics means that many operate unaware of the security implications of their work, and others are unprepared to respond to ethical or security challenges when they arise.

ENABLING PROBLEMATIC RESEARCH PRACTICES

The complex layers of authority and shifting-risk dynamics outlined in the previous section have profound implications for interactions with research subjects and local partners. Subjects lack the protections they would be afforded in Europe and the United States. Research partners might be incentivized by the personal and professional benefits that accrue from being affiliated with foreign academics. These power dynamics and incentive structures are not always immediately obvious, but failing to consider them can lead scholars to inadvertently engage in harmful or exploitative practices. In the sections that follow we outline the ways in which volatility and conflict can overshadow relationships between researchers and their subjects, partners and assistants.

Research Subjects: Vulnerable Populations

In the early 1960s, journalist Edward Behr overheard a British television reporter demand of survivors of the hostage crisis at Stanleyville, Congo: “Anyone here been raped and speaks English?” This anecdote sounds antiquated, but we have heard countless stories that are alarmingly reminiscent of this encounter. Academics researching civilian victimization or torture report the ease with which vulnerable populations can be accessed in fragile and violent contexts. Many colleagues recount stories of local fixers accompanying them in the early days of their fieldwork to hospitals or safe houses to speak with victims of horrific human rights abuses. Cronin-Furman witnessed an official offer to set up an impromptu meeting with war-crimes survivors for a group of undergraduate students on a postconflict study trip.

In Europe and North America, regulatory structures dictate that research with vulnerable populations follows extended discussion or long-standing relationships built over time with relevant authorities or organizations, and it must be firmly justified by its expected benefit. Researchers cannot simply arrive at a safe house or a domestic-violence shelter and demand to interview victims. However, such conduct is common in many fragile and violent settings, where victims and perpetrators of trauma frequently are the subjects of academic study. City of Joy, a community for women survivors of violence in eastern Democratic Republic (DR) of Congo, became such a frequent stop for Western researchers that its founders eventually closed the door to visitors.Footnote 5 Similarly, although none of the researchers we spoke with admitted to exploiting access to confidential medical, police, and court records to recruit interviewees or research subjects, many pointed out how easily they could have done so. In several cases, our colleagues reported that organizations were more than willing to share identifying details including names, telephone numbers, and addresses of service beneficiaries.

Ethical challenges continue to arise when researchers recruit interviewees in the most professional manner possible. In contexts dominated by international-development assistance, for example, it can be challenging for researchers to separate themselves from the aid organizations with which local populations are accustomed to interacting. Conversations with white women carrying notebooks can generate certain expectations, and being mistakenly associated with aid agencies and service providers works to the researchers’ advantage.

Wood (Reference Wood2006) discussed the frequency with which she was assumed to be a church worker when conducting her research on civilian victimization in El Salvador. Others emphasized the regularity with which residents at their field sites requested money to feed and clothe their children, assistance seeking visas or refugee status, and help obtaining medical care. Lake (Reference Lake2018) and Lake, Muthaka, and Walker (Reference Lake, Muthaka and Walker2016) encountered many individuals who expressed hope that support would result from sharing their stories with researchers. The reality that few people read unpublished dissertation research can make the concept of informed consent seem disingenuous, particularly when accompanied by the refrain: “We are happy to speak to you, because we want to share our stories with the world.” Even when academics do their best to make clear to potential interviewees that they will receive no direct benefit from participating in the research, it can be challenging to be confident that the message is heard.

D’Errico et al. (2013, 53) observed visible frustration with academic research that failed to deliver local benefits. One focus-group participant asked whether foreign professors are paid to teach classes based on the knowledge gained from visits to eastern DR Congo, suggesting that such payments should be shared with their informants. Another participant noted: “They say they can’t pay us [for research] because that would be unethical, but they take our dignity for free.”Footnote 6

Many researchers we spoke to similarly alluded to the phenomenon of “profiting off of information extraction”; for example:

How do I respect the safety, security, and integrity of my informants, where there is such a clear power and benefits disparity? Because I’m white, will they speak to me even though it may present a danger (that I don’t know about) to them in the future? How can I honestly portray my research and the real potential it has to be beneficial to them while still accomplishing what I need to accomplish?Footnote 7

Uncomfortable with the extractive nature of receiving information for nothing, many colleagues reported transgressing their defined interviewer–interviewee boundaries by offering compensation or accompanying research subjects to hospitals or clinics after interviews were completed. Understandably, they felt it was “the least they could do.”Footnote 8 However, many also were concerned that providing this type of assistance might not only complicate the expected impartiality and objectivity between researchers and subjects but also perpetuate the expectation that benefits accrue from consenting to being interviewed. In some instances, it can be difficult to dispel the concern that interviewees consent to participate in academic studies in the hope of remuneration, even when they have been clearly informed otherwise.

Uncomfortable with the extractive nature of receiving information for nothing, many colleagues reported transgressing their defined interviewer–interviewee boundaries by offering compensation or accompanying research subjects to hospitals or clinics after interviews were completed.

The readiness with which interviewees disclose their experiences as victims of trauma—even when that is not the subject of the research—poses another ethical challenge. As one colleague noted: “[My] interviews felt very strongly like therapy sessions, and when I would leave, I was often profoundly thanked for listening.”Footnote 9 Another related the following:

I had to comfort victims of sexual violence [which] was difficult, not only because I am not trained to do so but because they somehow expected me to. I had to explain that my role as a researcher would limit what I could provide to the subjects, but that I was ready to provide them with any help I had the capacity to provide.Footnote 10

Some scholars working on conflict have training that equips them for these interactions, but this is not the norm. Without professional training, retraumatization or other adverse consequences can result for even the most thoughtful and sensitive of researchers. However, firsthand research with such populations continues to be highly valued—and frequently rewarded—professionally (Driscoll and Schuster Reference Driscoll and Schuster2017; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2017). Scholars are commended for conducting original research, even when NGOs or other researchers have already done so. More disconcerting, researchers are applauded for their bravery and innovation when traveling to “dangerous” field sites or presenting research with ex-combatants or other vulnerable populations, despite a lack of experience or training. It is extremely rare to hear questions posed in academic presentations about research ethics or security, despite the fact that these power disparities call into question the fiction of informed consent.

Research Subjects: Elites

The effects of fragile and violent contexts on relationships with elites and organizations manifest differently but also are characterized by levels of access unparalleled in environments of greater institutional stability. Researchers that we spoke with reported (with chagrin) securing appointments with high-level officials simply by showing up at government offices. Junior scholars can conduct interviews with government ministers, high-court judges, and even presidents and prime ministers without prior notice. Moreover, many of our colleagues reported that powerful interlocutors had facilitated their research by making introductions to other elites, expediting security approvals, and providing access to government data and personal telephone numbers for follow-up questions.

The impromptu nature of these types of interactions can result from differences in social and professional norms across different country contexts. However, they also can result from mistaken identity. As Brown (Reference Lekha Sriram, King, Mertus, Martin-Ortega and Herman2009) noted about his research in Malawi:

I have no doubt that many Malawian officials and donor representatives (my main interlocutors) saw me around town, noted with whom I was socializing and associated me with the American government crowd….Once a US Embassy security guard let me through to someone’s office without checking for identification or phoning ahead—clearly against security protocols—presumably because he thought I was an American official.

Brown did not purposefully mislead his interviewees, but he was conscious of how his off-duty conduct influenced perceptions. Assumptions are made on the basis of race and nationality, and academics working in sub-Saharan Africa know that white skin or a Western passport opens doors.Footnote 11 Even when a researcher is inexperienced or lacking credentials, efforts may be made by senior officials to permit access to restricted data or respond to researcher requests with speed, deference, and ceremony.

Whereas these dynamics can affect research throughout the developing world, a particularly strong reliance on international donors can amplify this expectation in fragile or violent settings. Because many organizations receive revenue from foreign donors—that may occasionally visit field offices during funding visits—foreign researchers can be implicitly associated with international networks, connections, and hopes of future funding. An NGO director in a well-studied conflict zone joked that 90% of his time is spent fielding questions from American PhD students. NGO staffers in each of our research sites have reported feelings of duty or obligation regarding requests from Western researchers, sometimes resulting from ambiguity about who they are and what their potential or future position of influence might be.

Research Partners

The power imbalances between Western researchers and local organizations in conflict or postconflict contexts become more problematic when the relationship is not that of researcher–subject but instead research partners. Partnerships take many forms. Organizations may serve as “host” institutions, lending desk space or a formal affiliation to a researcher or a team. NGOs may serve as project implementers who are delegated to coordinate, oversee, monitor, and/or evaluate research activities for a negotiated fee. They may be service providers who agree to randomize aspects of their programs. These relationships often appear (and, indeed, can be) mutually beneficial. Yet, the realities of implementation reveal decisions and dilemmas that call into question the principle of “do no harm.”

Much has already been written about the ethical issues that plague field experiments and randomized control trials (RCTs). Challenges that prove difficult to overcome in the developing world are almost always compounded in fragile states where oversight of research is limited and researchers are, in practice, almost entirely responsible for policing their own ethical conduct. Even where researchers do due diligence to abide by relevant local regulations, the difficulty in identifying them can render good-faith compliance challenging.

For the inattentive or less scrupulous, limited monitoring and enforcement—as well as contradictions within the law—can make the rules easy to circumvent. These trends led Desposato (Reference Desposato2014a) to describe experimental research in the developing world as a “wild west where anything goes.” Pointing to the example of researchers hiring locals to commit traffic violations in an effort to investigate bribery and corruption across Latin America (Fried, Lagunes, and Venkataramani Reference Fried, Lagunes and Venkataramani2010), among other examples, Desposato noted that academics too frequently engage in research that transgresses ethics requirements or breaks national law.Footnote 12

Working through local partner organizations is one way that field experimenters attentive to these challenges have sought to mitigate harm to local communities. The logic is that local partners are more knowledgeable of the legal context in which they are working, as well as the potential pitfalls of the research design regarding ethics concerns. Humphreys (Reference Humphreys2014) explained as follows:

Even if they are not critical for implementation, partnerships can simplify the ethics. The decision to implement is taken not by the researcher but by an actor better equipped to assess risks and to respond to adverse outcomes.

However, local organizations do not always employ scrupulous ethical practice. The perverse incentives discussed previously raise the possibility that local organizations may sacrifice their own standards or disregard risks and ethics concerns in exchange for the benefits of affiliating with a wealthy foreign university. One researcher working in a highly volatile research context attended a focus group that had been organized by her partner organization without her knowledge. Despite assurances from the organization that all of the participants were comfortable participating, it transpired that some were frightened by certain other attendees. Seeking advice from her partner organization, our colleague was assured that the organizers knew better than she did. Given her knowledge of the political context, she knew that her participants did not feel safe and were screening information. She terminated the project. Had she been less knowledgeable, however, she might have taken the partner’s words at face value. Western researchers cannot simply absolve their own ethical obligations by shifting responsibility to local partners.

Research Partners: Research Assistants

Scholars often arrive at new research sites with limited prior knowledge. When working in volatile, dangerous, and unfamiliar settings, they rely heavily on fixers, RAs, and other local staff. These relationships are fundamental to successful research and often are how we learn about new research contexts. However, they can raise ethical issues of their own.

For partners whose role is formalized through pay or otherwise (e.g., RAs, fixers, interns, or survey administrators), the concerns are explicit: Are they paid enough for the work that they do? Is their contribution to the intellectual product recognized? Local RAs frequently assume responsibility for organizing every aspect of large- and small-scale projects: arranging interviews, providing contacts, organizing drivers, making travel arrangements, organizing research permits, obtaining visas, translating, and paying informal fees. For larger projects, they might conduct surveys, facilitate or organize trainings, reserve conference space, organize equipment, and manage teams of local staff. In a politically volatile research climate, this work can pose immense personal risks to the RAs and their families.

These individuals often are paid shockingly little for their contributions. RAs that we spoke to reported receiving wages as low as $37 a month. Widespread poverty and unemployment in conflict and postconflict environments make it possible to find local support staff eager for any form of employment. The extent to which NGOs and other external actors monopolize local economies in conflict or postconflict settings means that affiliating with foreign individuals and institutions may be perceived as the only option for exit or for an above-subsistence living. Out-of-work or underpaid professionals may affiliate with foreign researchers for little or even no pay in the hope that doing so could lead to future employment, educational opportunities, or open other doors. Work experience, introductions to other researchers, and the prospect that research with a foreign national will make them more attractive to foreign NGOs are powerful motivators to work for free. Yet, future opportunities only occasionally materialize.

If the unspoken promise of future employment allows researchers access to skilled labor at rock-bottom prices, it is not only their budgets that benefit. Frequently, locals advise on core substantive elements of academic projects. They play critical roles in designing studies, conducting analysis, interpreting data, and informing the conclusions that researchers draw. Yet, their contributions rarely are recognized beyond a footnote. In some cases, their absence may result from legitimate security concerns. However, it often reflects an assumption that these research partners do not share in the intellectual ownership of the work, which has resulted in the widespread erasure of local contributions from many published studies. Journals are so accustomed to seeing only European and American names on research projects undertaken in the global south that the fact that crucial African, Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latin American contributors are rendered invisible at publication rarely catches the attention of editors or reviewers.

This is not to say that researchers do not value the work of their partners. Many feel profound gratitude to their RAs and have built lasting relationships with them. Several colleagues spoke of developing close relationships, writing recommendation letters, paying for schooling, advising or supporting visa and asylum processes, and sending money to assist with family crises. Nevertheless, local labor contributes to publications, research funding, doctoral degrees, and tenure and promotion for scholars, few of whose benefits they share.

Contexts of state fragility or violent conflict constitute permissive environments in which researchers can find themselves (usually unintentionally) skirting the edges of what would be considered responsible research practice elsewhere.

CAN WE DO BETTER?

Contexts of state fragility or violent conflict constitute permissive environments in which researchers can find themselves (usually unintentionally) skirting the edges of what would be considered responsible research practice elsewhere. Their incentive structures, as well as those of their research subjects and local partners, generate potentially exploitative dynamics. Academics are rewarded professionally for firsthand insight and experience of the sociopolitical contexts that they are studying. With limited budgets and competitive tenure and promotion processes, environments that permit sensational or large-impact projects, which can be completed quickly and at low cost, make appealing research sites. The comparatively disempowered position of local research subjects and partners may lead to acquiescence in decisions and practices that cause discomfort and harm.

Some of the most valuable research in political science has come from careful research across methodological traditions in exactly the settings described in this article. Blattman and Annan (Reference Blattman and Annan2015), Cohen (Reference Cohen2013), Hoover Green (Reference Hoover Green2016), Mampilly (Reference Mampilly2011), Parkinson (Reference Parkinson2016), Shesterinina (Reference Shesterinina2016), Straus (Reference Straus2006), Weinstein (Reference Weinstein2007), Wood (Reference Wood2003), and others highlighted the complexities of participation in violence. Berry (Reference Berry2018), Fujii (Reference Fujii2010), and Thomson (Reference Thomson2013) provided illuminating testimonies of political persecution.

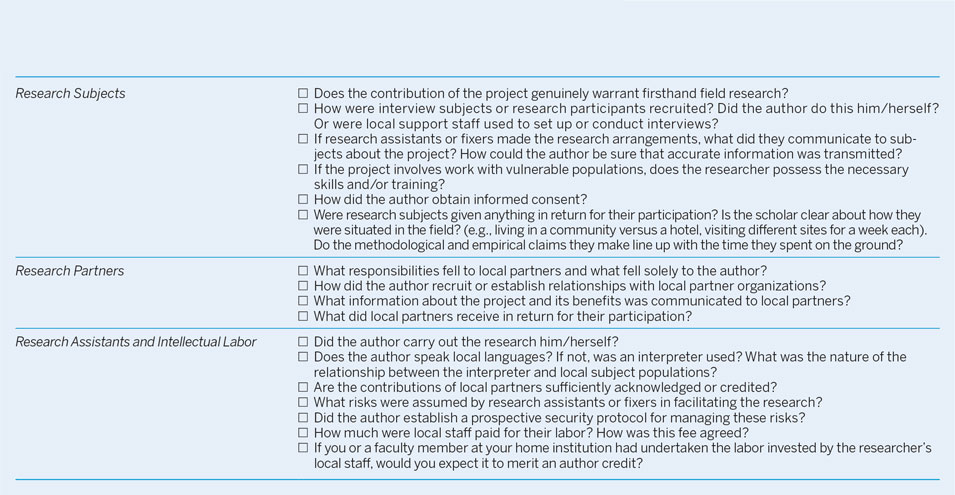

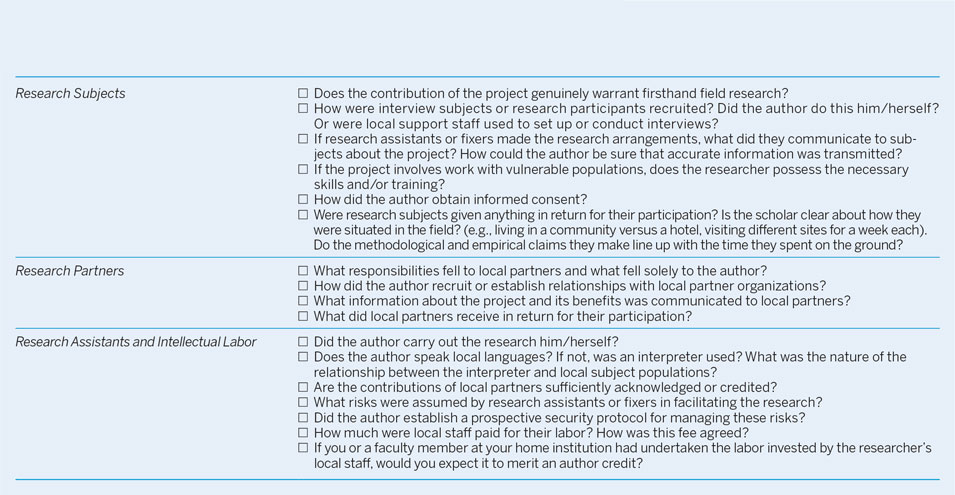

Our observations do not suggest a moratorium on research in fragile and violent contexts, but they do mean being attentive to—and working to combat—potentially exploitative dynamics. Becoming sufficiently acquainted with social and political norms to confidently navigate risk can take time that academics do not always have.Footnote 13 However, there are measures that researchers can take to better prepare for the ethical challenges they may face in the field. Drawing on the observations of researchers working in violent and fragile contexts across multiple methodological traditions, table 1 delineates a set of concrete questions and recommendations to guide scholars embarking on this type of research.

Table 1 Questions for Consideration by Scholars Embarking on Field Research

Yet, it is not only individual researchers who need to be more reflective about the ethical implications of work in fragile and violent contexts. As a research community, we also can do more to ensure that researchers who travel to work in these settings are appropriately trained and prepared, that ethically problematic research is not rewarded, and that the contributions of local partners are adequately credited. Lone questions about ethics at conference presentations should not be dismissed as peripheral to a study’s theoretical innovation. Conference attendees, faculty advisers, grant evaluators, journal editors, anonymous reviewers, dissertation committees, and readers should all engage in critical evaluation of the relative value of any academic research project—particularly if it is conducted by inexperienced researchers—vis-à-vis the potential harms inflicted.

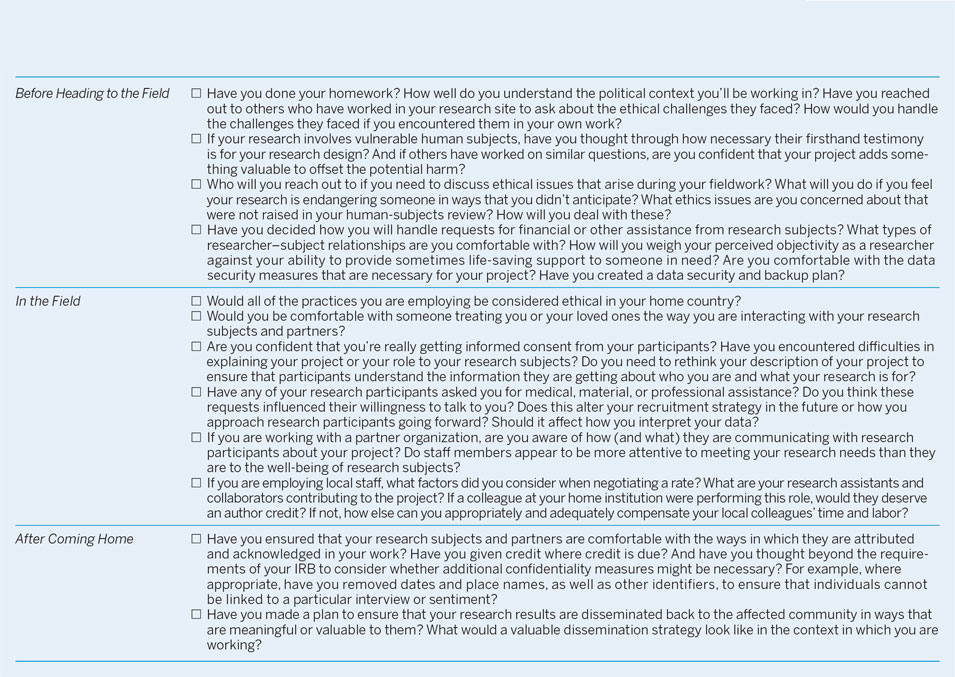

As suggested in table 2, these audiences should consider (and ask!) whether the study would be possible in their home countries; whether they would be comfortable if the study involved members of their own family; how visible and invisible power disparities were considered in the research design and implementation; whether participants appeared to have been exposed to risk; and whether the contributions of local partners were sufficiently credited. The social science community at large is obligated to relentlessly question whether the scientific contribution of the final product genuinely warranted sensitive firsthand research.

Table 2 Questions for Consideration by Reviewers and Readers