Introduction

This article focuses on the modular market structures that were introduced into public housing estates in Hong Kong in the 1960s and 1970s – the first ‘wet markets’ in the region. My aim is to examine how the market space, as an integral part of public housing, was constructed and managed to convey and adhere to government concepts of modernity in Hong Kong through modularity. As I will demonstrate, modular markets brought everyday negotiations of modernity to the fore, as both markets and homes (in the context of public housing estates) became more formalized in their design. In considering how the spaces of markets in Hong Kong housing estates underwent ‘containment’ in accordance with colonial ideas about hygiene, consumption and social order, this article not only seeks to write the market back into the social history of post-war Hong Kong, but also responds to wider calls in urban history literature for ‘empirical studies…of how urban markets function in and for the modern city’ – especially in ‘non-western’ settings.Footnote 1

The period of development between the late 1950s and 1970s in Hong Kong introduced what is now commonly known in English as ‘wet markets’ into the urban landscape. As this term becomes increasingly debated in mainstream and academic discourses of non-western (particularly East and Southeast Asian) markets, there is an urgency for in-depth contextualization and theorization of these spaces. Although the etymology of ‘wet market’ is unclear, the OED traces its origin to post-colonial Singapore in reference to Housing Development Board (Singapore's public housing estates) market spaces in the 1970s.Footnote 2 This is also the case in Hong Kong, where the term ‘wet market’ seems to have been popularized by English-speaking ‘bi-cultural’ communities before being used in reference to public markets.Footnote 3

I will first draw on the existing literature concerning markets and public housing in Hong Kong, before calling attention to markets that were designed and built specifically for public housing estate communities from 1969 to 1975, using colonial government documents and photographs to explore the nature of the modular markets and their use in public housing estates. I will then expand on the language of ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ before finally referring to the broader history of Hong Kong's markets to theorize ‘wetness’ in relation to negotiating colonial notions of ‘modern’ space, hygiene and bodily control in the post-war period. The article borrows from Tani Barlow's seminal work on ‘colonial modernity’ as ‘a speculative frame for…posing a historical question about how our mutual present came to take its apparent shape’ and the suggestion that historical context is ‘a complex field of relationships or threads of material that connect multiply in space-time and can be surveyed from specific sites’ as opposed to ‘defined, elemental or discrete units’.Footnote 4 In this study, modernity is thus understood not merely in the top-down adoption and execution of ‘defined units’ of construction and organization, but also in cross-examining everyday ‘material relationships or threads’ in the colonial urban landscape, by speculating on the history of ‘wetness’ in the specific site of the wet market.

Hong Kong markets in modernity

Jon Stobart and Ilja Van Damme relate the gap in the historical scholarship of ‘the market’ to the abstraction of the market space as the institutionalized economy of the metropolis.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, urban markets in their physical form have received renewed attention in other disciplines in the last two decades, particularly in non-western contexts. Several themes dominate the resulting discourse. First, informality continues to be a persistent theme, for instance, with many recent works asserting the co-existence and co-operation of structures of formality and informality of markets, found in policies, buildings and the actions of individual actors, rather than simply top-down forces.Footnote 6 Related to this is gentrification and urban conflict surrounding urban markets, particularly tied into heritage, tourism and place-making, regarding them as central to the negotiation of identity, memory, hybridity and diversity.Footnote 7 Secondly, other studies point to the broader conflicts between market stalls, organizers and consumers, against urban gentrification tactics by local governments and urban planners.Footnote 8 Thirdly, markets have also been sites of urban histories of public health, hygiene and epidemics, designed to separate communities along race and class lines spurred by the racialization of epidemic outbreaks and disease, but where human activity and infection nevertheless spill out and cross over these boundaries.Footnote 9 In many cases, this intersects with histories of housing, particularly where residential and commercial housing co-exist. On a more local level, contemporary studies have explored the change in perception of ‘hygiene’ by consumers in relation to the grocery shop.Footnote 10 Indeed in the aftermath of global epidemics such as SARS, avian flu and the continuing effects of COVID-19, all have brought the market back into mainstream and academic discourses of food management, hygiene, public health and the racialized tensions therein.Footnote 11

The patterns in the historiography of Hong Kong's markets follow the trends in the discourse of markets overall. Largely conducted by anthropologists and economists, the literature of Hong Kong markets focus on familiar themes of informality, precarity, competition and perception rather than on spatiality.Footnote 12 Aside from these works, the spatial and social aspects of markets have often been subsumed into the rich literature on hawkers. T.G. McGee's seminal study on hawkers in Hong Kong (1973), followed by the influential work of Josephine Smart (1989, 2005, 2017) has made Hong Kong hawkers, and their affiliated markets, a consistent reference in studies of informal economies and urban activity in cities across the world.Footnote 13 However, due to markets being intertwined with hawkers in the literature, the imagination of markets in Hong Kong rarely goes beyond the street market. The Cantonese term of gaai si 街市 literally translates to ‘street market’, but in contemporary use, gaai si can nevertheless be used to refer to markets on or off the street, and is much more related to the products sold and the manner in which these goods are consumed rather than the physical space in which the activity is conducted. The literature largely bypasses this, and markets are mostly presented as a ‘plural’ for hawkers, as the end form in which hawkers collect, or as the tool used for colonial control, rather than a subject for spatial historical analysis in their own right.

There are, however, several recent examples that focus on the spatial-material culture of markets in Hong Kong in relation to the history of the city.Footnote 14 These works successfully contextualize the market as a material or spatial entity intertwined in urban histories of hawkers, public health and urban planning. However, it is telling that all largely focus on some of the most architecturally distinctive models of markets in Hong Kong, anomalies of the type that are continuously visible under the tourist gaze as relics of the early colonial era. It is perhaps this dichotomous divide of Hong Kong's hawkers and markets, ‘from’ one to replace ‘the other’, from ‘dirty’ to ‘sanitary’, as several titles suggest, or the continuous focus on Central Market in particular, that means the literature has rarely coalesced in a broader understanding of markets in Hong Kong as numerous, messy and deeply integrated local sites of spatiality and materiality. This article thus begins to fill the gap between the polarized nineteenth-century and contemporary readings of the market, shifting the focus of the history of markets in Hong Kong beyond its urban core towards the New Towns.

Towards public housing and modular space in Hong Kong

Modular architecture, construction and concepts were increasingly prevalent globally as a post-war rebuilding strategy. While standardization as a design theoretical framework has a much longer history through industrialization, particular cases of modernist modular architecture and city planning from the late nineteenth century onwards have been celebrated for spatial, technological or conceptual standardization.Footnote 15 Oft-cited is Le Corbusier's concept of The Modulor (1948), which aimed to create a visual system for design based on the human body, against the clash of imperial and metric systems of measure.Footnote 16 This was an explicitly modern endeavour, lamenting that ‘modern society lacks a common measure capable of ordering the dimensions that which contain and that which is contained’.Footnote 17 In short, spatial modularization also involved a ‘modularization of society’. This measured link between humans and buildings, in which the ideal modern architecture fulfils the role of ‘containing’ man ‘harmoniously’ through appropriate measurements and ratios, was a particularly useful concept in colonial rebuilding efforts and production of social housing in the post-war period.Footnote 18

Lack of space and overcrowded housing was a persistent issue from the outset in colonial Hong Kong.Footnote 19 During the 1950s, Hong Kong's population rose dramatically, largely due to people returning to or fleeing to Hong Kong from China to escape the newly established People's Republic of China, with the population reaching around 2.5 million by 1955.Footnote 20 Many poorer refugees were living in squalid conditions in squatter settlements on the peripheries of the urban centres, where fires were frequent occurrences.Footnote 21 Following the infamous Shek Kip Mei fire in 1953, two new government departments were formed under the 1954 Housing Ordinance specifically to deal with housing this population, the Resettlement Department (RD) to house victims of fire and resettling refugees, and the Housing Authority (former HA) for higher income households.Footnote 22 In 1961, the Government Low Cost Housing scheme (GLCH) was established for households with an income below HKD$600 but were not part of resettlement programmes.Footnote 23 After the introduction of the 10 Year Housing Programme in 1973, all three housing types were merged under the new Housing Department and the new Hong Kong Housing Authority.Footnote 24

A significant motivation for government public housing was to redistribute the population outwards and into the New Territories in order to regain the use of valuable land. As a result, a majority of public housing estates were built on the peripheries of the urban centres to become central nodes of nominated ‘satellite towns’, eventually formalized as New Towns. In the first phase, these were Kwun Tong, Tsuen Wan, followed by Tuen Mun and Sha Tin. While some of these towns were well established, all these districts were significantly urbanized after public housing schemes were initiated, employing design and engineering innovations to reclaim land, and build higher, more efficient structures at low costs and high speeds.Footnote 25 Between 1960 and 1970, 10 resettlement and GLCH estates were built in Kwun Tong and Tsuen Wan with an estimated total population of 267,470 people by 1967.Footnote 26 In spite of the drastic changes in the population in these New Towns, it was often only the housing itself that was developed at such a rate – many aspects of public life, including markets, relied heavily on the existing social structures in place, vastly outnumbered by the newly expanded population.Footnote 27 Nevertheless, this intense period of urbanization simultaneously satisfied government needs for more space and dispersal of people (particularly following the 1966 and 1967 unrests), and appeasing the population through evidence of social reform.

Colin Bramwell's 1969 modular market stall

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the lack of market buildings as part of these public housing estates resulted in a surge of illegal hawking. Tactics such as hawker bazaars constructed by the Architectural Office (AO) in the late 1950s, could not meet the demands of the growing population of the New Towns, where lack of mobility and access into the central urban districts encouraged illegal hawking to thrive.Footnote 28 However, in the late 1960s, further co-operation between government bodies began to manifest in more consistent solutions for markets. After the drafting and release of the Colony Outline Plan (COP) in 1969, a comprehensive review of the future population distribution and land use, the strategy for markets became more directed towards standardized concrete structures.Footnote 29

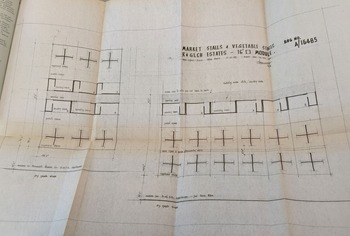

In resettlement and low-cost housing estates, two main policies were agreed by the Market, Hawker Management, Resettlement Policy and Resettlement Management Committees in March 1969: first, for properly designated and constructed small markets to be provided in estates under planning and future estates; and secondly, where practical, for construction of small markets in existing estates to be covered in the upcoming Public Works Programme.Footnote 30 However, with the dire hawker problem at hand in existing resettlement estates, immediate provisions were also necessary. Together the Urban Services Department (USD) and RD consulted Public Works Department (PWD) architect, Mr Colin Bramwell, ‘regarding the feasibility of providing a relatively quick and economical design for a market stall which would meet hygiene requirements’.Footnote 31 The result was a modular market stall, originally intended for selling fruit and vegetables in low-cost housing estates that could be easily modified for the ‘restricted’ foods of meat, fish, and poultry. Figure 1 shows how the modules could fit together: modules could sit side by side, or back to back, containing the scalding areas of ‘restricted’ goods away from public view, and smaller open stalls could form around cross panels facing out toward the dry goods shops on the ground floors of estates. The design was lauded for ‘its standard 16-foot square modules, suited to easy and flexible planning, and speedy and economic construction’, flexible enough to adjust to the spatial limitations of existing estates, and also meant to meet the demands of the severely underserviced market needs in estates.Footnote 32 This modular structure would mark the first standardized design strategy to attempt to remove all restricted food types from street hawking practices to be implemented on a widespread scale.Footnote 33

Figure 1. Hong Kong, Public Records Office, HKRS 438-1-78, Urban Council Hong Kong, Minutes of Meetings of Select Committees Dealing with…April 1969 – March 1970, market stalls and vegetable stalls R + GLCH estates, 17 October 1969.

Ahead of its implementation at Sau Mau Ping Estate, a model of the market was set up at Chai Wan for Urban Council members and the public to inspect.Footnote 34 Photographs of the model stall at Chai Wan Resettlement Estate give a clearer picture of each complete module (Figure 2). Retaining the cuboid forms of the housing estates themselves, the flat roof and slim perpendicular wall structures give a visual and material consistency of solid clean lines and block shapes coated in pale paint, in stark contrast to the haphazard and precarious structures spilling out of the Chai Wan hawker bazaar (Figure 3). Shelves line the sections around the panels for hawkers, and at the other end, a built surface for use by those selling meat and fish consisting of simply a long concrete block, contained within three walls with access to the service way behind. The built-in table runs almost to meet the opposite wall, demarcating a clear boundary between buyer and seller. Indeed, the distinct visual boundaries and structures of the two types of stalls reflected the separated administrative procedure that arose with the modular market. Where fruit and vegetable hawkers would continue to pay for hawker licences and rent, initially HKD$20 per month, meat, fish and poultry stalls were put up for auction to bid for the rental price by the fresh provision hawkers already operating in the estates.Footnote 35

Figure 2. Hong Kong, Government Information Services, 352–6555/12, new kinds of hawker stalls (modular stalls) at Chai Wan, photograph by K.T. Leung, 27 May 1970.

Figure 3. Hong Kong, Government Information Services, 352–6555/1, new kinds of hawker stalls (modular stalls) at Chai Wan, photograph by K.T. Leung, 27 May 1970.

While Bramwell's modular market design seemed like a simple exercise in problem-solving, the design also reflected a decade of discussions around industrialized, prefabricated and modular construction in Hong Kong and other British colonies.Footnote 36 Although the UK Ministry of Works was keen to promote the new British industry of prefabricated buildings to the colonies as an ideal solution to housing problems and post-war re-urbanization in the early 1950s, Hong Kong was not among the territories to import the product.Footnote 37 By this time, Hong Kong was already overwhelmed with squatter fires and a dire housing crisis.Footnote 38 Single-storey buildings with prefabricated units were considered but, according to local architects, the major ‘drawback was that the ground coverage would have been far too high and less than one third of the homeless could be accommodated on the site cleared by the fire’.Footnote 39 Likewise, experts were dubious that prefabrication was even possible in Hong Kong due to the lack of heavy industry and the logistics of transporting the units through the narrow and crowded streets.Footnote 40 With these two constraints, standardization was limited to using simple construction methods and minimal equipment with precasting of concrete slabs on site, until the mid-1960s when the former HA development of Fuk Loi Estate in Tsuen Wan first tested the Japanese ‘Tilt-Up’ method in the Hong Kong context.Footnote 41

At the same time, the concept of the module was increasingly part of the international discourse of planning and architecture, including Hong Kong.Footnote 42 Indeed, the standard ‘unit’ already dictated Hong Kong public housing design and production, where the Hong Kong government resettlement space allowance was strictly set to 24 square feet per adult resulting in a 120 square foot unit for a total of five adults (where children counted as half an adult) in order to significantly house the population.Footnote 43 In other types of public housing, the legal minimum standard was 35 square feet per adult. Again, the lack of local heavy industry meant concrete was cast in slabs on site rather than precast into set modules.Footnote 44 But the ‘modularization of society’ was still present through the organization of people in these spaces. By strictly assigning square footage to individuals, government bodies could theoretically calculate and ‘predict’ estate populations and ‘optimize’ (essentially, significantly reduce) the space used per person. While Hong Kong architects and planners were clearly aware of global modes of housing construction, prefabrication and standardization, they also actively took their own route into modernizing their development procedures to suit their own local needs.

As a PWD architect also designing public housing, these strict units used in housing design undoubtedly informed Bramwell's modular approach to the market in public housing estates as well.Footnote 45 Hawker numbers were set in the COP in 1969, recommending 153 stalls to 10,000 persons, or approximately 1 stall to 60 persons, a number derived from hawker surveys in existing urban areas in 1966 (largely Yau Ma Tei).Footnote 46 This strategy was not only practical for reducing numbers, but also for hygienic spatial order and management. Modularization and industrialization allowed for quick and efficient construction that could restrict the amount of space used by each hawker and the number of hawkers of each food type. This therefore also clearly demarcated the boundaries of legality, where previously one of the challenges of hawker management in the late 1950s and early 1960s was simply identifying and suppressing illegal activity. With this new outline, it was finally clarified which department was responsible for controlling which space:

management of the future markets in Estates will be the responsibility of the Urban Services Department, but staff of the Resettlement Department will be responsible for demolishing illegal hawker stalls found outside of the boundaries of the markets…The Police will also be requested to take action against illegal cooked or restricted food hawkers in the vicinity of these markets.Footnote 47

Through the modular market, the public housing estate market could be visually and spatially standardized across public housing estates for the first time, creating clear boundaries between legal and illegal hawker practices. Within the market, the spatial order was maintained through the modular structure as well; this can be clearly seen in Figures 4 and 5, where the structures of the ceiling, partition walls and the cast iron drain covers in the centre demarcated the boundaries for each hawker's stall. Hawkers’ legal status was bound to material and administrative infrastructures, requiring them to take part in orders of hygiene, licensing and space in order to continue practising.

Figure 4. Hong Kong, Information Services Department Photo Library, GIS 123 7834/28, Kwai Hing low-cost housing estate, taken by C.W. Wan, 7 January 1972.

Figure 5. Hong Kong, Information Services Department Photo Library, GIS 123 7828/6, Kwai Hing low-cost housing estate, taken by P. Chow, 3 January 1972.

Managing markets, containing wetness

Management became increasingly significant in the success of estate markets as informants for containment methods and structures. This also inevitably influenced improvements in the market's design. A small-scale internal survey was carried out in 1972 by housing managers on the design of market stalls in three estates designed by different groups, Wah Fu Estate (former HA), Kwai Hing Estate (PWD) and Mei Foo Sun Chuen Estate (private).Footnote 48 The findings showed that all three markets were poorly lit, had insufficient storage space and ceiling height, inefficient drainage, with further observations by housing Architect 2 on site adding more consideration of user experience and management.Footnote 49 Indeed, the survey reveals that even prior to government administrative reconstruction in 1973, architects and managers on the ground were already attempting to progress the design standards of the markets within the structure of modularization.

Most significantly, potential risks to hygiene and spatial order could be mitigated further through the design of the modular market interior in response to the environment. Containing the materiality of ‘wet’ goods and the hawker practices surrounding them proved to be central to design specifications. Managers specified that floor finishes for fish and poultry stalls (the main stalls dealing with slaughter and butchery on site) especially ‘should be of more durable type’ due to constant washing, the ‘floor is unable to be kept dry because of the nature of trades’.Footnote 50 Efficient and constant drainage was therefore also paramount, so that wastewater could be quickly flushed to minimize slippage and contamination. As well as sealing against contaminated water, another manager suggested ‘It would be advantageous to have mosaic tiles on dadoes on walls that attract most dirt and grease’ to preserve the market's aesthetic values.Footnote 51

However, not all wetness could be practically solved. Weather was severe, with nine Signal 10 typhoons in Hong Kong between 1960 and 1979 as well as two significant rainstorms, often causing major damage to estate structures through wind damage and landslides.Footnote 52 Wetness permeated the market, both as a source of life, lustre and cleanliness, and as a constant threat to the government's vision of a clean, modern, working society and urban landscape.Footnote 53

This is further emphasized in the language of ‘wet’ in the categorization of food, which in turn designated how these goods could legally be exchanged in the urban landscape. The terms ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ were in administrative use to describe market goods since at least the early 1970s, which may be related to the vernacular Cantonese sap fo 濕貨 (‘wet goods’) and gon fo 乾貨 (‘dry goods’).Footnote 54 These have been broadly defined in government documents, generally designating perishable goods as ‘wet’, and non-perishable goods as ‘dry’, although there is no comprehensive list. Instead, a list specifying ‘commodities allowed to be sold by hawkers’ (1969) gives a clearer idea of what constituted ‘unrestricted’ goods. These were separated into three classes: vegetables or fruit (not both together); permitted food stuffs other than vegetables or fruit, which included eggs, dried meat and salt fish, vermicelli and preserved vegetables among others; and mostly non-food ‘dry’ goods. Finally it specified why meat, fish and poultry should not be permitted.Footnote 55 Later on, the Urban Council Policy Manual (1975) categorized ‘the usual commodities sold in markets’ into five categories of fresh produce: meat; fish; poultry; vegetables and fruits; and ‘other’ foods such as eggs and bean curd, plus non-perishable frozen, dried or packaged foods.Footnote 56 It should also be noted that, according to Gary Luk's research, these categories were already regarded as ‘departments’ in the design of Central Market in 1842.Footnote 57

Despite the vague definitions of wet and dry goods, post-war government policies and manuals made clear that the purpose of the market prioritized the containment and regulation of the most vulnerable foodstuffs to contamination, especially as meat, fish and poultry, including live animals, were the only goods explicitly barred from hawker sales.Footnote 58 In 1969, the Urban Council did not initially approve of hawkers selling restricted goods in any capacity, justifying market buildings in the belief that ‘existing illegal hawkers of meat, fish and poultry have already shown a total disregard for the basic hygiene requirements (ample clean fresh water, clean implements and clean working conditions) and there is no reason to believe that legalizing them would alter their attitude’.Footnote 59 While the idea of containing wet goods has a much longer history, the widespread containment of wet goods first trialled through the modular market, alongside the adoption of ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ categories in markets in the 1970s, arguably introduced the popular notion of the ‘wet market’ as a distinct space in colonial Hong Kong.Footnote 60 Still, in spite of the hard colonial structures setting out the physical and administrative boundaries for hawkers, such fluid, vernacular terminology allowed for potential transgressions by hawkers and consumers alike.

Market materiality: consuming fresh ‘wet’ goods

‘Wetness’ was also integral to improving the viability of the market for both hawkers and consumers, in spite of the inconveniences and risk of ‘wet’ goods.Footnote 61 Surface materials, wall colours, lighting, spatial arrangements and storage were all considered in great depth to highlight the most important quality of ‘wet’ goods in the eyes of consumers – ‘freshness’.Footnote 62 Exchanges between Architect 2 and the housing managers show how intimately aware all sides were of cultural customs and practice of the market, and so designed to navigate these needs while satisfying their own management and hygiene specifications. Although impractical for managing health and safety, live fish and poultry were integral goods offered in the market, and therefore easy access to both salt and freshwater was deemed necessary.Footnote 63 Refrigeration or cold storage were essential for a number of trades (fruits, butchers, fishmongers, frozen foods) and therefore power outlets to cater for these stalls were added to the design.Footnote 64 Allowing small buckets of water by hawker stalls, vegetables ‘may be watered at internals in order to maintain its freshness’ and make them ‘look fresh and luster [sic]’, perhaps considering angled lighting to reduce direct heat and light on the products.Footnote 65

Interestingly, such efforts to present a modern market space were often re-narrated by the behaviours of consumers themselves. A 1974 survey conducted by the Planning Division of shoppers in public housing estates found that the Chinese understanding of freshness in food differed greatly from the administration's proclaimed ‘modern’ ideas of fresh, bemoaning that ‘in spite of modern appliances such as the refrigerator, nearly all the hawker customers still maintain the habit of shopping once or twice daily for “fresh” food’.Footnote 66 Working-class Chinese women were particularly accused of being archaic and too discriminating, thus perpetuating outdated modes of consumption, ‘even go[ing] to the extreme of “ransacking” for what they want’.Footnote 67 This tactile, sensory recognition of freshness in the market continues to be a significant part of embodied knowledge in Chinese cooking practices where strategies such as checking the clarity, shine and fullness of fish eyes, and indeed overlooking the slaughter of live fish and poultry to discern ‘real’, fresh produce, relate to scrutinizing the quality and freshness of goods.Footnote 68 Perceived as illogical, scrutinizing, messy and slow, it was, however, precisely these continuations of relational exchanges that facilitated everyday colonial modernities for the lives of consumers. In consuming and selling across boundaries of legality and acceptability, emphasizing freshness and wetness as central to their everyday practices, hawkers and residents could in turn appropriate these colonial spaces beyond government imaginations of modern urban space and life while remaining within colonial modular structures designed to discipline. Bound by their need to create capital and persuade the public of certain behaviours and boundaries, government departments and management were forced to compromise on modes of modern consumption in order for these spaces to succeed.

In this sense, the diverging discernment of the materiality of ‘fresh’ market goods, the environment of the market and how these goods respond to such conditions are played out in the notion of ‘wet’. Returning to colonial modernity, Barlow's more recent proposal to ‘look again at colonial modernity through questions of selling and buying’ can be seen in the example of the wet market as a space where objects are exchanged, but also as a space made of exchange of ideas of modernity.Footnote 69 While managers largely focused on functional and aesthetic value in their recommendations, the undertone throughout the discussion remained focused on designing an orderly and hygienic market space.Footnote 70 From the government categorization, ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ in administrative terms were consistently more concerned with the materiality of the goods (vulnerability to decay) than the spatial condition of the market (the physical wet floors and damp environment). However, the material relationship between wet goods, the spatial environment and consumers within modular markets directly informed the design choices by architects and managers as a means of control. This, together with the sensorial, tactile experience of sap fo by consumers, expanded the meaning of ‘wet’ to emphasize the unstable, visceral nature of the produce, and the potential threat to the body and social order that this instability might bring.Footnote 71 Colonial modernity therefore can be expressed in the ‘wet market’ not only as a structure, but as the constant navigation and rearrangement of modernity in this space through the materiality of goods and ideas of the modern body.

Conclusion

The construction of modular markets in Hong Kong's public housing estates in the late 1960s and early 1970s introduced the notion of the ‘standard unit’, borrowing from strategies in public housing, to everyday consumption spaces and practices. While it was logistically unfeasible for the Hong Kong government to construct prefabricated modules for public housing, the smaller scale of the modular market meant that it could fulfil the ‘modernist ideals’ of efficient construction, standardized space and order as attempted in Britain and other colonies. This demonstrates another mode of ‘modularization of society’, not only confined to housing but also extending into the public realm of estates. Modules physically laid out the spatial and legal boundaries of the market, which allowed for more manageable arrangements of policing tied to boundaries of inside and outside the market and estate area. In doing so, the Hong Kong government created a new urban space embedded in public housing that facilitated closer surveillance and control of hawker practices and consumption habits, particularly in the containment of visceral ‘wet’ goods and ‘wet’ activity, enabling a social and spatial disciplining towards their colonial vision of modernized society. The modular market set the foundation for formalized consumption space in public housing estates, only superseded by multi-storey markets and commercial complexes in larger estates in the late 1970s.Footnote 72 Nevertheless, such structural forms were reappropriated and re-narrated through the behaviours and antagonisms of hawkers and consumers, such that the role of wet markets in contemporary Hong Kong has taken on its own life in the everyday negotiations of the city. Thus, while modularization took place on a structural and social level, the fluidity of ‘wet’ goods and their materialities offered avenues for transgression and appropriation of market spaces.

A design historical and material approach offers an alternative lens on Hong Kong's post-war public market structures as design entities in themselves, entangled with the global politics of markets in Asia, and containing its own history of colonialism and modernity. Hong Kong's unique historical and geographic conditions (and specifically venturing beyond the urban centre) offer a more nuanced approach to the market as a source of life and space of control. Indeed, the theorization of the term ‘wet’ is useful when considering this space; not simply ‘because the floor is always wet’, wetness, in the sense of the visceral, sensorial properties of the goods and space, allows for multiple readings of modernity in the ‘wet’ market to take place, bringing navigations of modern consumer practices and systems of management to the fore as distinctive forms of colonial modernity.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr Jeremy E. Taylor for guidance through this research and for comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Funding Statement

Research for this article was undertaken under the COTCA project. This project received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Number 682081).