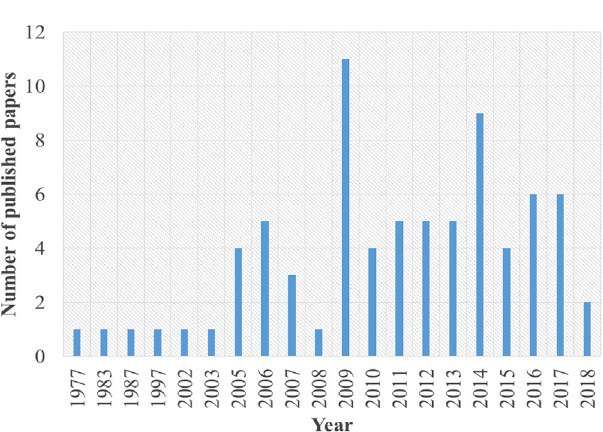

The paper by Brugger, Kurthen, Rashidi-Ranjbar and Leggenhager describes how individuals who are “potential medical specialists” compare to those who are not in perceiving causal attributions in a rare condition, xenomelia. This work is timely given that since the first description in 1977, we witnessed a raise in studies in 2009 and in 2014, but the general trend is of 3.8 papers per year (Fig. 1). Compared to other rare conditions, such as Capgras syndrome or Alien Hand syndrome, the difference is striking. Between 1977 and 2018, 549 papers have been published on Capgras and 176 on Alien Hand.Footnote 1 Hence, this paper is fundamental to understand this different attitude towards xenomelia, and what can be done to get out of the quicksand in which we have ended up.

Fig 1. Number of papers as a function of published year. Source: Pubmed (keywords used for search: Apotemnophilia, Body Integrity Identity Disorder, Xenomelia) and Sedda & Bottini 2014. Total number of identified studies that directly explore/describe/review the condition: 76. Time range of publications: 41 years. Publications peak: 2009 (n = 11) and 2014 (n = 9).

Firstly, we should define the “social matters” worth exploring to understand xenomelia aetiology. Social and cultural components have not been systematically explored yet in this condition. First, in 2005, described some “social” components in the individuals participating in his study Reference First[3]. For instance, relationship patters and the role of seeing an amputee during childhood in the onset of the desire, features that have been considered also in following studies [Reference Khalil and Richa4, Reference Sedda and Bottini5]. However, studies should also include measurable psychosocial variables such as empathy, indexes of the influence of media on behaviours (i.e. use of forums dedicated to the condition) and copying strategies to mention some Reference Brugger, Lenggenhager and Giummarra[2]. This list is not exhaustive, neither it covers the idea of a culturally bound syndrome. We still lack cross cultural studies, comparing individuals with xenomelia in different countries to explore the role of culture. Most studies provide a picture for specific Western countries Reference Sedda and Bottini[5]. A recent review of cases in non-Western countries Reference Blom, Vulink, van der Wal, Nakamae, Tan and Derks[1] elicits interesting starting points on this culture role. For instance, one of the patients described in the Chinese literature reports that being “disabled granted her attention from others that she had always missed from her parents” (Reference Blom, Vulink, van der Wal, Nakamae, Tan and Derks[1], p. 1421) in clear opposition from what is known about the Western cases of xenomelia [Reference First3–Reference Sedda and Bottini5]. Even within Western studies, culture might have a role in differentiating features between European and American individuals. If “Access to and nature of care will heavily depend on the emerging definitions of such conditions” (Reference Brugger, Kurthen, Rashidi-Ranjbar and Lenggenhager[6], p. 46) then the future of understanding xenomelia relies on multidisciplinary studies including biological, social and cultural components. Furthermore, attitudes towards social matters were explored in European individuals. Is culture also playing a role in how professionals perceive xenomelia and is this impacting the disclosure of the condition? The work on non-Western countries by Blom et al. seems to point in this direction Reference Blom, Vulink, van der Wal, Nakamae, Tan and Derks[1]. In summary, culture might play a role not only in xenomelia aetiology but also in its expression and reception within societies. Similarly, it should not be taken for granted that “potential medical specialists” and not medical specialists interpret social and cultural variables the same way. Even more a definition of these variables is needed.

Another important missing data is the perspective of individuals affected by xenomelia on this brain-mind relationship matter. A unidirectional brain-mind bias would imply a different compliance/preference towards possible treatments. Most individuals who tried psychological therapies found them ineffective and dropped out [Reference Khalil and Richa4, Reference Sedda and Bottini5]. Similarly, drugs adopted until now do not change xenomelia symptoms [Reference Khalil and Richa4, Reference Sedda and Bottini5]. A brain-based condition could be perceived as less within the control of the individual and resulting in a higher demand for amputation treatments rather than mind oriented therapies perceived as less cost-effective [Reference Khalil and Richa4, Reference Sedda and Bottini5].

In conclusion, Brugger et al. paper should guide the development of future studies on xenomelia. We need to include biological, social and cultural components, but for the latter ones we need an operational definition of which components and why. This definition is still lacking, while neuroscientific studies benefit from a clear direction towards exploring more known body representation components Reference Sedda and Bottini[5]. Secondly, we need to know more about the individuals with xenomelia perspective on this causality relationship, as “patients” are the main actors in clinical settings and without their compliance any effort towards providing support or a treatment is ineffective.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.