Introduction

Recent years have seen a (welcomed) boom in literature on debates around decolonising the curriculum which now takes on many different (often overlapping) registers including, but not limited to, diversifying, internationalisation and/or activism. Nevertheless, we cannot escape the fact that decolonising the curriculum has also become a sound bite, crudely hijacked by neoliberal university managers as a way to recruit more students (Sian, Reference Sian2019; Bhambra et al., Reference Bhambra, Nişancıoğlu and Gebrial2020). In this sense, rather than representing a real commitment to equality in education, decolonising the curriculum is instead deployed as a marketing strapline that features in university brochures. For right-wing critics, decolonising the curriculum signals a threat to the old way of doing things, a hostile and unnecessary attack on European knowledge, culture and tradition (Forbes, Reference Forbes2018).

Decolonising the curriculum thus means different things in different contexts, and like many concepts, it has arguably been generalised to the extent that it has ceased to do the work initially expected of it (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed and Sian2014). In some arenas, this has led to a superficial engagement with the term – reduced to a slogan on a T-Shirt that anyone can wear – rather than a critique of power structures. As Rodriguez points out, ‘the terminology has started to evoke a practice of getting rid of colonial and imperialistic practices by the very same people who are not only operating fully under those practices but who also receive full financial benefit from them‘ (2018: 11). This article aligns itself with a critical understanding of decolonising the curriculum: that is, framing it as a political project requiring analytically to examine, collectively challenge, and creatively reflect upon the embeddedness of Eurocentric discourse and praxis, which not only dominate the syllabus, but also feed into the broader structures of ‘Western’ universities (Amin, Reference Amin1989). Decolonising the curriculum also involves an ‘unlearning’ (Rodriguez, Reference Rodriguez2018: 1) and disrupting of hegemonic epistemologies and practices – an intervention which has a series of conceptual, methodological and institutional corollaries.

This article will focus on decolonising the sociology curriculum, with particular attention being placed upon mainstream sociology’s (mis)understanding of communities of colour, but the critique can be read across to related disciplines. It questions the very foundations of the discipline and offers a critique of its inherent Eurocentrism (Morris, Reference Morris2015). The article then goes on to examine ways in which such thought continues to shape and influence contemporary sociological understandings of the ‘other’, which remain locked into a culturally reductive, essentialist lens. After mapping out these conceptual concerns, I examine how Eurocentrism is also manifested at the methodological level, particularly in the study of communities of colour which are currently analysed for the most part through a colonial gaze. It will question the appropriateness of the methodological tools traditionally deployed by social scientists and explore the possibility of developing alternative ways of ‘doing’.

Finally, the article reflects upon the institutional transformations required to enable a more diverse and inclusive sociology curriculum, and the various challenges that confront such a call. This section is informed directly by the voices and experiences of academics of colour, and highlights both the constraints and potential rewards around decolonising the curriculum. The data drawn upon comes from twenty in-depth interviews conducted between 2018–2019 with academics of colour working in British universities. The women and men interviewed were at different stages of their academic careers and on both permanent and fixed-term contracts. They were based in the social sciences and worked at different institutions across the country, including both Russell Group and Post-92 universities (Sian, Reference Sian2019). Following this discussion, I conclude by arguing that the promise of a decolonised sociology cannot be simply reduced to cosmetic changes: it must demonstrate a wider commitment to anti-racism and social justice.

Conceptual concerns

In broad terms, sociology is concerned with the emergence of modern society: however, it is somewhat perplexing that the sociological imagination has for decades neglected the role of coloniality in accounts of modernity, despite its centrality (Sian, Reference Sian2014). As Mignolo (Reference Mignolo2011) argues, coloniality represents the ‘darker side‘ of modernity. For Mignolo, the hegemonic discourse on modernity has celebrated Europe and the advent of modern society whilst simultaneously hiding the horrors of colonialism. That is, the racist practices established by colonial systems to advance the modern project have been obscured and absent from mainstream analyses of society. If we are fully to commit to decolonising sociology, perhaps the most important starting point would be to go back to the foundations of the discipline to unmask its colonial underpinnings and examine its contemporary manifestations.

Arguably sociology has been one of the key social sciences to have produced knowledge that subordinates and regulates non-European societies. This is perhaps unsurprising when we consider the beginnings of the discipline. Sociology emerged against the backdrop of a series of transformations including the political, industrial and scientific revolutions that characterised much of the nineteenth century (Bhambra, Reference Bhambra2007). The European Enlightenment was key in heralding a new age symbolised by science, rationality and reason. This thought directly informed the discipline which became fundamentally concerned with a scientific analysis of modernity and its effects on society. Coined by Comte, sociology refers to ‘a positive science of society’ (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton, Hall and Gieben1992: 20). Positivism became the cornerstone of sociological thinking (and doing), guided by Enlightenment principles of empiricism, objectivity and universalism (Agozino, Reference Agozino2003: 92). In its broadest sense, positivism can be seen as a philosophical discourse that proposes that all social phenomena can be examined and analysed through a scientific method (Sian, Reference Sian2017). It is an epistemological position that rejects social constructionism and genealogical accounts (ibid). Positivist thought is rooted in the idea that scientific knowledge can be applied to the study of natural and social life, which produces universal laws that govern the world (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton, Hall and Gieben1992: 21). In this sense, societies can be understood via empirical facts that generate objective and value-free knowledge.

Positivism can be seen as the foundation of Eurocentric thought, deeply intertwined with colonialism and racism (and sexism). It adhered to the new-founded desire to generate classifications and hierarchies to groups and organise different communities. In this way, it mirrored nineteenth century Enlightenment ideas that sought to categorise non-White, non-Western peoples as inherently inferior, as Lander argues:

Sharing the main assumptions and prejudices of nineteenth-century European thought (scientific racism, patriarchy, the idea of progress), positivism reaffirms the colonial discourse. The continent is imagined from a single voice, with a single subject: white, masculine, urban, cosmopolitan. The rest, the majority, is the ‘other,’ barbarian, primitive, black, Indian, who has nothing to contribute to the future of these societies (Lander, Reference Lander2000: 520).

These essentialist frameworks have continued to haunt the sociological imagination and can perhaps be seen most prominently in analyses of racially-marked communities that have migrated and settled in the West. When accounting for the experiences of ex-colonial subjects relocated in the metropole, many sociological accounts continue to frame the migratory and settlement process through cultural and/or biological frameworks underpinned by Eurocentrism (Sayyid, Reference Sayyid, Law, Phillips and Turney2004; Sian, Reference Sian2013). Sayyid argues that in such narrations there is a clear set of distinctions made between the host and the migrant, which he refers to as the immigrant imaginary (ibid.: 150–153).

The immigrant imaginary is an orientalist device deployed by scholars and commentators to account for non-western experiences in which the political is replaced by discourses centred upon ethnicity, culture and biology (ibid.). It provides a catalogue of highly mobile tropes that have been used over decades to mark out communities of colour. Sayyid argues that there are four key features of the immigrant imaginary. First is the idea that there is a fixed, ontological distinction between host and migrant (ibid.: 150). Secondly, communities of colour are viewed as only ‘exotic’ or ‘banal.’ The exotic is represented through a superficial celebration of difference, such as ritual, dress and customs (ibid.: 151). The banal is linked to ideas of colour blindness and the reluctance to recognise the different, varied and textured historical trajectories of migrants. Third is the idea that migrants will (and should) integrate fully into the host culture through a process of uncritical assimilation: it assumes that the destiny of communities of colour is total assimilation into the majority community (ibid.). The final feature of the immigrant imaginary is centred upon the theme of generational progress. Here each generation of migrants marks progress towards integration: however, the categories of first, second or third generation conveniently defer the moment when migrants can be considered full members of society. In this sense, the migrant will always represent that of a newcomer (ibid.: 151–152).

The immigrant imaginary can be found circulating widely in academic (and popular) culture (ibid.: 152). Perhaps one of the key sociological paradigms that can be seen to reaffirm this framework is that of the ‘culture clash.’ The culture clash is the idea that migrants are seen to encounter an innate struggle between their ‘traditional’ culture and the modern values of the west (Anwar, Reference Anwar1998). As Ngo (Reference Ngo2008: 4) points out, one of the key dimensions of this paradigm is the focus on the distinction between migrant and host cultures with the familiar dualisms of traditional/modern or rural/urban to account for differences between the two cultures. This convenient binary is rehashed time and time again to suggest that there is an intergenerational conflict between the younger generations who want to enjoy the Western lifestyle, and older generations seen to hold on to restrictive, traditional values, depicting them as, ‘backward or stuck in time’ (ibid.: 5).

The sociological focus on ‘culture clashes’ is problematic for a number of reasons, as Ngo points out: ‘the emphasis on traditional cultural values reifies the notion of culture, positioning it as something that is fixed or a given, rather than as a social process that finds meaning within social relationships and practices’ (ibid). Such a reading of identity therefore turns what could be considered generic behavior (i.e. youth rebellion, struggles for autonomy) into a marker of cultural specificity (Sian, Reference Sian2013). Furthermore, these accounts rely primarily upon a crude cultural determinism, which fails to account for wider social exclusionary practices that impact upon the identities of racially-marked communities (Ngo, Reference Ngo2008: 5).

These essentialist frameworks have been attributed to communities of colour since the earliest days of mass settlement and continue to seep into contemporary academic accounts (Sian, Reference Sian2013). This has been particularly exaggerated in the wake of the war on terror, which prompted a renewed fascination around the ‘incompatible’ and ‘irregular’ cultural and religious practices of Muslim communities (Lewis, Reference Lewis2002; Roy, Reference Roy, Holoch and Columbia2007). These lazy, but all too familiar, discourses on communities of colour reduce their identities to merely that which is passive, static and unchanging, rather than that which is fluid, multifaceted and fundamentally political. What becomes clear here is the way in which Eurocentric knowledge continues to underpin much of mainstream sociology, whereby the ‘other’ remains a subject that lacks agency and can only be read in contrast to the idea of the West. These conceptual representations work to erase the experiences and voices of communities of colour constructed as objects of study, rather than active participants in the shaping of society and the discipline itself. Those critical voices that have challenged these discourses have often been pushed to the margins of the discipline, found in sub-areas such as, ‘postcolonial studies,’ ‘cultural studies,’ and ‘black studies.’

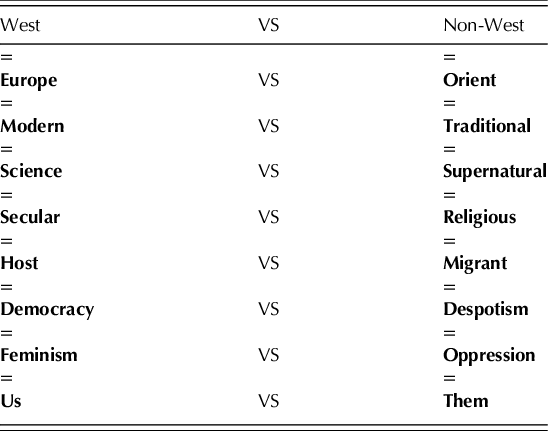

It could be argued then that mainstream sociology has been guilty of reproducing repressive narratives based on a Eurocentric worldview that uncritically reinforces reductive binaries. In this way, mainstream sociological accounts can be seen to partake in epistemic violence when analysing the formation of communities of colour in the West (Spivak, Reference Spivak, Nelson and Grossberg1998; Santos, Reference Santos and Sian2014). It has also been responsible for expanding the chain of equivalence (Laclau and Mouffe, Reference Laclau and Mouffe1985) that serves to maintain the imagined superiority of the West (see Table 1).

Table 1 Chain of equivalence between the West and Non-West

This hegemonic structuring shapes much sociological analysis on communities of colour, which as we have seen, are reduced to culturally-essentialist accounts that validate Eurocentric epistemologies. In this way, mainstream sociology can only ever represent a limited view of the world. The key steps towards decolonising sociology at the conceptual level would therefore have to involve a deep recognition of the racial genealogy of the discipline, which as we have seen, is steeped in European ideas of cultural superiority, as Lander points out:

The implications for non-Western societies and for subaltern and excluded subjects around the world would be quite different if colonialism, imperialism, racism, and sexism were thought of not as regretful by-products of modern Europe, but as part of the conditions that made the modern West possible (Lander, Reference Lander2000: 525).

Such a recognition is vital to present a more nuanced, textured and critical account of modern society and its settlers. Decolonising also requires a commitment to dismantling the hegemonic, essentialising binaries that sustain forms of Western supremacy. That is, understandings and examinations of the non-West must be broadened beyond a Eurocentric lens that simply situates their subjectivities as inferior. Their voices and contributions must be represented fully in accounts of modern society: that is, legitimate political subjects who have actively shaped the history and formation of the West.

Methodological concerns

Related to the issues explored above, I now address the problems arising from social science research and offer a critique of the methodological tools so commonly deployed when ‘studying’ communities of colour. Positivist epistemologies are foundational to sociological research which is based upon key principles including: originality, theoretically-informed, systematic and adhering to scientific method, generalisability, and following ethical guidelines (Patel, Reference Patel2017: 158). The key objective of sociological research is thus to discover ‘truth’ and generate new knowledge through the application of different methodologies to the given area of interest (ibid). In the broadest sense, quantitative methods are most explicitly linked to positivism and are fundamentally concerned with objectivity to produce numerical data via questionnaires, large surveys, and statistical tests (ibid: 159). Qualitative methods on the other hand favour interpretivist models that rely upon understanding experiences through ethnographic techniques such as (but not limited to), in-depth interviews, focus groups, participant observation, and document analysis (ibid.). On the surface qualitative research is seen to represent a key shift from positivism, in that the data generated is subjective; however, the reality is that for the most part it suffers from the same Eurocentric bias, producing the same Eurocentric conclusions, the only difference being the route taken to get there. Both qualitative and quantitative methodologies have therefore been deeply problematic in research on communities of colour, often producing data that reaffirms racial hierarchies: indeed, as Smith points out: ‘the term ‘research’ is inextricably linked to European imperialism and colonialism’ (Smith, Reference Smith1999: 1).

Social science research has as such produced arguably some of the most dangerous knowledge, from Lombroso’s racist measurements of skulls to classify criminals (Sian, Reference Sian2017), to the all too-common ethnographic exploitations which see communities of colour being studied through a white gaze, constructing them as essentially different, deviant and/or inferior (Patel, Reference Patel2017: 162). This sentiment is further elaborated upon by Smith who argues:

It galls us that Western researchers and intellectuals can assume to know all that it is possible to know of us, on the basis of their brief encounters with some of us. It appals us that the West can desire, extract and claim ownership of our ways of knowing, our imagery, the things we create and produce, and then simultaneously reject the people who created and developed those ideas and seek to deny them further opportunities to be creators of their own culture and own nations (1999: 1).

Such intrusions, in the name of qualitative social scientific research, have unsurprisingly led to ‘fatigue, hostility and suspicion’ among communities of colour. As Patel suggests, they have felt that they have been ‘over-researched’ particularly on topics around educational attainment and intelligence, parenting styles, deviance and crime (2017: 163). This has understandably created a lack of trust or ‘weariness’ among communities of colour whereby they are all too often ‘used as mere “objects” of research rather than subjects’ (Sanghera and Thapar-Björkert, Reference Sanghera and Thapar-Björkert2008: 552). Sanghera and Thapar-Björkert go on to describe that it is often felt that researchers ‘“parachute in” and leave once they have conducted their research, and nothing is seen or heard from them thereafter’ (ibid.). In addition to this, members of the community are often both dissatisfied with the way in which researchers fail to provide feedback, and remain anxious about the way in which the data may be (mis)used (ibid.). In this sense we can see an exploitative and unethical power dynamic play out between the white researcher and non-white subject whose experiences, as I have argued, ‘are capitalised upon to serve white gain, white fame, and white career-driven interests’ (Sian, Reference Sian2019: 163).

Quantitative methods are just as dangerous in the study of communities of colour and also warrant critique. Bonilla-Silva and Zuberi make a particularly compelling argument that alerts us to the way in which statistical analysis was established in conjunction with notions of racial classifications and reasoning; as they point out, ‘the historical trajectory of the application of statistical methods to the study of society developed in relation to European contact, colonisation, trade, and domination of peoples thought to be beyond modern civilisation’ (2008: 5). The founders of the social sciences thus utilised statistical analysis to demonstrate and institutionalise ideas of racial inferiority through a scientific veneer (ibid.: Sian, Reference Sian2017): that is, ‘the birth of racial statistics gave scientific credibility to justifications of racial inequalities’ (Bonilla-Silva and Zuberi, Reference Bonilla-Silva, Zuberi, Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva2008: 6). The latter thus argue that the use of such data in the social sciences cannot be untangled from the eugenics movement, which sought to account for social status and achievement through racial hierarchies, as they go on to explain:

Early in its development, social statistics were inextricably linked to the numerical analysis of human difference. Eugenic ideas were at the heart of the development of statistical logic. This statistical logic, as well as the regression-type models that they employed, is the foundation on which modern statistical analysis is based (ibid.: 8).

Reflection and recognition is thus significant if we are to decolonise social science research methodologies, particularly quantitative methods, which for the most part remain unopposed due to the assumption that they are ‘hard facts’ and therefore unchallengeable (Gordon, Reference Gordon and Skellington1996: 20). Social science research that produces quantitative, statistical data is often regarded as ‘superior’ as it is seen to comply more closely with the scientific method. As Gillborn argues, ‘statistics are often treated as a special form of research (viewed as complex, objective and factual) that can reveal hidden realities about the world’ (2010: 254). However, this notion is limited given that quantitative data, like all other forms of data, are subject to bias, false and misleading interpretations. As Gillborn goes on to point out, such methods, ‘encode particular assumptions which, in societies that are structured in racial domination, often carry biases that are likely to further discriminate against particular minoritized groups’ (ibid.).

This however is not to deny that statistics have proved valuable for anti-racist scholarship: indeed, they have been helpful to expose discriminatory practices and racial inequality (Gordon, Reference Gordon and Skellington1996; Bonilla-Silva and Zuberi, Reference Bonilla-Silva, Zuberi, Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva2008; Gillborn, Reference Gillborn2010). The point here is to acknowledge that this form of data is not ‘neutral’ or ‘objective’ – it is political and often serves different ideological interests (Gordon, Reference Gordon and Skellington1996: 28). It would be useful here to return to Bonilla-Silva and Zuberi’s recommendation (Reference Bonilla-Silva, Zuberi, Zuberi and Bonilla-Silva2008: 7) that social scientists must ‘demystify’ taken-for-granted ideas around racial statistics. In doing so we are perhaps more able to understand the way in which such data continues to be influenced by both external forces and researchers themselves who more than often reflect and project racial hierarchies.

As we have seen, the social sciences have almost exclusively applied Western, Eurocentric paradigms to research (Held, Reference Held2019: 1). A decolonial approach to research methodologies must commit to the decentring of these approaches and involve other ways of knowing. Furthermore, it must be a path towards social justice rather than a career-building exercise (Held, Reference Held2019; Sian, Reference Sian2019). Practically, this calls for sociologists critically to reflect upon the methodological tools that they employ; as Bonilla-Silva and Baiocchi propose, ‘the myth of objectivity and neutrality espoused by mainstream sociologists needs to be exposed’ (Reference Bonilla-Silva and Baiocchi2001: 127). Decolonial research also requires collaboration and on-going dialogue with activists, social movements, and communities of colour that is not simply fleeting, but rather long-lasting and participatory. Concretely, research departments should look to developing and forging intellectual networks with the Global South, where there are active shapers, rather than simply passive objects, of research processes (Patel, Reference Patel2014: 609). This would produce a more diverse, and global approach to research, whereby key insights, knowledge and critiques generated by communities of colour would be at the very heart of methodological designs and outcomes. That is, research would be conducted in partnership, rather than on the terms of white, Western academics. Reflexivity, criticality and engagement are crucial to ensure the production of ethical, non-exploitative research. In short, decolonial methodologies require a commitment to the dismantling of the hierarchy that exists between white researcher (coloniser), and non-white participant (colonised).

Institutional concerns

The third dimension of decolonising the curriculum focuses on the institutional concerns. Whilst previous sections examine decolonising the curriculum at the disciplinary level, institutional concerns emphasise the larger university objectives that must be addressed if a decolonised curriculum is to be fully implemented. Here I draw upon my interview data referenced earlier with academics of colour to highlight and reflect upon the various challenges and barriers around decolonising the curriculum within the university setting. Their experiences demonstrate the dismissive and often hostile reception from white colleagues and university managers when confronted with calls to decolonise the curriculum. There was a sense here that the work around decolonising the curriculum was seen as a burden by some white senior members of staff, as one participant recalled:

We’ve done some work previously on decolonising the curriculum, and I was on a committee where we were discussing plans for the next year. And a few of us, my other non-white colleagues, said let’s revisit that work, and a senior white colleague said ‘oh no we’ve already done that, staff don’t want to be overloaded with that stuff’.

This account demonstrates a clear reluctance from some white colleagues to engage with decolonising the curriculum, and also reflects ways in which calls from non-white members of staff are all too easily brushed aside and ignored. Furthermore, rather than seeing the value in decolonising the curriculum (that is, as a means to transform universities and teaching and learning agendas), white members of staff reduce the issue to a matter of ‘workload.’ Similar concerns around the lack of action by some white colleagues were also noted by another respondent:

We have to add diversity to the curriculum ourselves. It’s not in their (white colleagues’) inclination to change their reading list, they don’t want to add anything or take anything out, so anything more dynamic you have to add and you have to do the work of that. And you do it because – I think of it like – I want these students to be able to hold conversations with people across the world, and if you only know this narrow band of theorists, and don’t even know your own colonial history, when you leave and engage with other scholars, you’re going to look uneducated. So I try to, at the very least, expand my students’ thinking, but that’s all work you do on your own.

This response captures the way in which the labour around decolonising the curriculum appears almost always to fall on the shoulders of academics of colour, while there is very little interest or desire from some white colleagues to initiate or lead this change. The concerns around white colleagues appearing not to be making much effort around decolonising the curriculum were picked up across all of my interviews, as another participant said, ‘I would like to see white teaching staff challenge themselves and make the effort to include other materials, and diversify the staff.’ In a similar vein it was pointed out that, ‘decolonising the curriculum and issues around race should be seen as a positive thing in universities rather than as a chore.’ Following on from this, it was frequently expressed that issues of race and coloniality were side-lined and neglected across teaching and learning agendas: this was particularly evident when academics of colour attempted to introduce these topics onto their programmes, as one participant commented:

We’ve definitely had problems around introducing race-related courses to programmes, we’ve had push back at the management level who clearly don’t want race to feature as a central area. We don’t do anything on race, but it seems the decision-makers think we do too much, I don’t know where they get that idea from. But if decision-makers feel this way, then how are we ever going to move on?

Similarly, another respondent noted how, when he took on his course, race was marginalised from the material:

On the reading list when I took on this course, it was all white authors and thinkers, and race had been something that had been largely neglected. I found you could talk about race, but only in the context of gender and class, so race was never given prominence, it was always yes racism is bad, but so is patriarchy, sexism and so on, so we almost had to talk about all these issues in one where race was not allowed to be talked about on its own.

These responses highlight the way in which issues of race and coloniality have been largely invisiblised, positioned on the periphery of teaching programmes. My participants however pointed out that when they did teach students about these topics they responded positively, for example:

The feedback I get from my students, where my teaching is diverse, is that it’s life-changing – the knowledge or ideas. They are glad this content is taught, because it’s part of peoples lives. We need to do this more, but I think structurally you have to be in a position where you’re more senior where you’re able really to give everything a facelift, otherwise it’s just piecemeal.

Likewise, another interviewee commented: ‘when I’ve taught on the race modules I’ve found students have said this really changed the way they understood sociology and their everyday understandings of the world.’ Despite the positive experiences, academics of colour reported from students who had been taught from a more diverse programme, there was an overwhelming sense that universities were simply not interested in implementing a decolonised curriculum, therefore further reinforcing the notion that the labour around decolonising largely falls upon academics of colour: as one respondent commented: ‘…if I were to leave, the course would disappear, so one of the challenges is to make these embedded in the institution, rather than being dependent on one or two academics working in these areas.’ The next participant similarly expressed concerns around the way in which decolonising the curriculum appeared to be engaged with only at a superficial level across the university; fundamentally it was regarded as a ‘tick box’ exercise to fulfil the requirement of wider race initiatives:

With the new race initiatives in universities, I’ve seen how universities seem to only care about getting this badge. But at the political level in terms of systemic change, there’s no desire there to fully invest in or resource projects around decolonising the curriculum. It’s just lip service to give the impression they’re engaging with this.

The respondent went on to point out that the actual composition of the university, particularly at the managerial level, reinforces the feeling of a lack of systematic investment around diversity, equality and inclusion:

The status quo benefits certain individuals. The senior people in my department are white men; there are no women or BME people in senior positions of power. That’s the same with my university leadership team, so vice-chancellors are all white men. What image, what outward message are you giving to potential students? (ibid.)

The interview data reveals the institutional obstacles around decolonising the curriculum and the way in which many universities appear to be slow on the uptake, with little investment or desire to implement change. As we have seen, there are a clear set of constraints that academics of colour encounter when attempting to embed a curriculum that is inclusive and diverse within their universities. This reflects the broader systemic racism of British universities whereby the marginalisation of people of colour is not only restricted to the curriculum, but also in the make-up of the institutions themselves which are overwhelmingly white (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2012; Sian, Reference Sian2019). A broader commitment to anti-racism and social justice in universities is required. Such a commitment would recognise that racism affects the whole institution and is not simply a concern for staff and students of colour (Law et al., Reference Law, Phillips, Turney, Law, Phillips and Turney2004: 93). With this in mind, universities must also critically reflect upon the ways in which racism, colonialism, whiteness and Eurocentrism shape the environment both in a physical and conceptual sense (ibid.). This reflexivity is essential if universities are to begin to dismantle hegemonic forms of whiteness. Initiatives around decolonising the curriculum require investment from all members of staff and students; in this way it is has to be a collective undertaking, that is fully resourced, to ensure inclusive, and anti-racist futures in university settings and beyond (Sian, Reference Sian2019: 115). What has been argued, then, is that the changes required must be systemic: that is, the curriculum can only be more diverse and inclusive, when the university itself is more diverse and inclusive.

Conclusion

Much of Western European history conditions us to see human differences in simplistic opposition to each other: dominant/subordinate, good/bad, up/down superior/inferior. (Lorde, Reference Lorde1984: 114).

The critical literature on postcolonialism and decoloniality has paved the way for an important rethinking of knowledge production in the West (Said, Reference Said1978; Mohanty, Reference Mohanty1988; Hall, Reference Hall, Hall and Gieben1992; Fanon, Reference Fanon2001; Quijano, Reference Quijano2007; Mignolo, Reference Mignolo2011; Santos, Reference Santos and Sian2014), which for the most part has been structured around an oppositional binary. This article demonstrates that sociology represents one of the key disciplines reinforcing these Eurocentric frameworks. It argues that decolonising the curriculum must therefore include a commitment at three levels: the conceptual, the methodological and the institutional. This three-pronged approach means that decoloniality and anti-racism are profoundly embedded throughout the entire university, rather than just simply concerned with a handful of different courses and programmes. In this sense, the main thrust of the article has been to argue for the transformation of universities as well as disciplines. If we are to remain critical of Eurocentric knowledge formations at the disciplinary level, we cannot ignore the ways in which the university itself reinforces these hegemonies. As Sharma argues, a critical curriculum ‘would attempt to respond to the contemporary conditions of knowledge production – conditions in which university racisms remain an everyday reality of teaching and learning’ (Reference Sharma, Law, Phillips and Turney2004: 114). The recognition and reflexivity of how the conceptual, methodological and institutional interconnect and intertwine is crucial if universities are to represent decolonial spaces that can speak to current global issues.