Introduction

The interpretation of the Bible is at the core of doctrine in several of the largest religious traditions in the U.S. Thus, it is not too surprising that when survey researchers have sought to measure doctrinal beliefs in the American public, they have often asked about respondents' views of the Bible. Most previous work in political science and sociology that connects views of the Bible to politics has relied on a single question that offers respondents just three categories with which to classify how they interpret the Bible: as the actual word of God to be interpreted literally, as the word of God but not interpreted literally, or as a book written by men that is not God's word. This three-category approach has not only become the standard for measuring biblical views but is also the primary (and often the only) religious belief item on well-known omnibus surveys such as the American National Election Studies (ANES) and General Social Survey (GSS). The ANES item is worded as follows:

Which of these statements comes closest to describing your feelings about the Bible?

1. The Bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word.

2. The Bible is the word of God but not everything in it should be taken literally, word for word.

3. The Bible is a book written by men and is not the word of God.

The scholarly community has made extensive use of this measurement approach, employing it to classify groups of Protestants as fundamentalists (Hunter, Reference Hunter1981, Reference Hunter1991), and to predict a range of political attitudes and behaviors including, for example, party identification and vote choice (Kellstedt and Smidt, Reference Kellstedt, Smidt, Leege and Kellstedt1993), opposition to same-sex marriage (Becker and Scheufele, Reference Becker and Scheufele2009; Whitehead, Reference Whitehead2010; Perry, Reference Perry2015), support for punishment (Unnever and Cullen, Reference Unnever and Cullen2006, Reference Unnever and Cullen2010), opposition to environmental protection (Guth et al., Reference Guth, Green, Kellstedt and Smidt1995), and knowledge about science (Zigerell, Reference Zigerell2012).

Despite the frequent use of the three-category item, there are important concerns about exactly what it is measuring. First, the standard item poses a double-barreled question: Is the Bible the actual Word of God? AND Is the Bible to be taken literally, word for word? Research has shown how double-barreled questions can induce measurement error (Krosnick and Presser, Reference Krosnick, Presser, Wright and Marsden2010; Menold, Reference Menold2020; Pew Research Center, n.d.). In the case of the Bible items, the response options are conceptually distinct but are combined in the options offered to respondents. This combining of components increases the cognitive demands on respondents by forcing them to consider more information. In addition, respondents might have different responses to each component of the double-barreled item. These features of double-barreled questions are problematic outcomes that can contribute to measurement error (Sinkowitz-Cochran, Reference Sinkowitz-Cochran2013; Menold, Reference Menold2020).Footnote 1

Along with being double-barreled, the phrasing of the standard Bible item leaves considerable room for interpretation as to its meaning. When a respondent selects the first option for literal interpretation, he or she may have in mind a hermeneutical approach that relies on the plain meaning of the text rather than allegorical or figurative interpretations—likely the meaning that many scholars intend when they employ the survey item (see, e.g., Klein et al., Reference Klein, Blomberg and Hubbard2017). But it is also quite plausible that the respondent may view the first option as an appealing one simply because it expresses the strongest endorsement of the veracity of the Bible—that it is the “actual Word of God.” In that case the respondent may not even consider interpretive strategies when forming her answer, yet would be classified as a “literalist.” Or perhaps choosing the first option carries a connotation that the Bible is important and relevant to the respondent; that is, its content reflects actual events that still matter today. Indeed, many Americans today use the word “literally” as a device for emphasis, almost interchangeably with “really” or “truly” or “actually.” In these cases, a survey taker's selection may be classified as an “expressive response” (see, e.g., Paulhus, Reference Paulhus, Robinson, Shaver and Wrightsman1991; Berinsky, Reference Berinsky2018). So, what are respondents really telling us when they answer the views of the Bible question?

To the extent that different respondents interpret the standard views of the Bible item differently, the danger of measurement error is heightened. In other words, the basket researchers think is holding apples may also include several oranges or pears. The result may be a misrepresentation of the distribution of views Americans hold about interpreting the Bible, and, more importantly, a loss of clarity about the relationship between biblical views and political attitudes and behaviors.

In this paper, we assess the measurement error in the standard three-category question about views of the Bible by developing new items to gage the various aspects of what it might mean to a respondent to select one of the three options in the standard Bible question. Using original data from two online surveys we analyze the correlates of the standard item and show that our new items not only predict responses to the standard ANES item but also are potent predictors of political attitudes—at times performing better than the widely used three-category question.

The paper proceeds as follows. First, we briefly review previous work examining views of the Bible and identify potential weaknesses in the standard approach. We then present our data that allow us to compare responses to the standard item with responses to our new items, and to examine their relationships to political variables. We conclude with a discussion of the findings and recommendations for researchers wishing to measure doctrinal views in future surveys.

Views of the Bible: measuring literalism or something else?

Prior research has called into question what the standard Bible item measures. One line of work examined the differences between asking about literalism versus inerrancy. Jelen (Reference Jelen1989) compared two question wordings in the 1985 GSS—one that emphasized inerrancy (“The Bible is God's word and all it says is true”), versus one that emphasized literalism (“The Bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word”). Jelen did not find statistically significant differences in how the two items related to ten political variables. These results suggested that individuals in the mass public did not draw the same distinctions between literalism and inerrancy that religious elites might make. But, in a follow-up study, Jelen et al. (Reference Jelen, Wilcox and Smidt1990) did find meaningful differences in political and religious attitudes when comparing respondents who selected a literalism option versus those who selected an inerrancy option. However, the data for their study came from a survey of 271 African Americans in the Washington, DC metro area, raising questions about the generalizability of the findings. So, the empirical evidence on the interpretation of response options for Bible views items is mixed.

Other work examining survey measures of biblical views has noted a strong tendency for respondents to place themselves in categories that express favorable views of the Bible, even when other indicators of religiosity would suggest less favorable responses. In a thorough examination of the correlates of Bible views, Kellstedt and Smidt (Reference Kellstedt, Smidt, Leege and Kellstedt1993) summarize their findings as follows: “We have found that responses to the literalism and inerrancy measures are highly skewed in the direction of positive or favorable answers to the Bible questions. When two-thirds of the respondents who express no religious preference give positive responses to the Bible, … something is wrong with the measure if it is to be tapping religious, rather than cultural, responses” (194, emphasis in original). While the percentage of the public who rejects the authenticity of the Bible has grown in recent decades (Saad, Reference Saad2017), substantial support remains for self-identified Christians (Burge, Reference Burge2017). The positive cultural connotation among the religious (and even the non-religious) reduces the usefulness of the existing items to parse the effects of religion.

Subsequent research has also made the argument that the typical Bible views items capture a cultural identity rather than simply measuring religious views. Franzen and Griebel (Reference Franzen and Griebel2013) analyze the social and political antecedents of responses to the Bible item in multivariate models. They find that many demographic and political variables are more strongly correlated with views of the Bible than are religious variables, leading the authors to conclude that the typical survey item is “not simply a measure of religiosity, but a specific political-religious identity” (Franzen and Griebel, Reference Franzen and Griebel2013, 538). Thus, when a respondent attempts to formulate an answer to the standard Bible views item, “they are not only declaring religious behaviors and beliefs, but also associating with an identity” (Franzen and Griebel, Reference Franzen and Griebel2013, 538). This fits with research that suggests issue attitudes may signify symbolic identity (Ellis and Stimson, Reference Ellis and Stimson2012; Mason, Reference Mason2018a, Reference Mason2018b).

An implication of this previous work is that the standard ANES views of the Bible item is not measuring what many researchers think it is measuring. Scholars who want to understand the influence of varying approaches to biblical interpretation will need additional measures. In the next section we discuss our new measures of biblical interpretation and analyze their effectiveness.

Data and measures

Our data are drawn from two online surveys we conducted using samples provided by Survey Sampling International (SSI), which is now Dynata. First, in June 2015, we recruited 1,200 evangelical Christian respondents via SSI to take a survey online. Evangelicals were identified by asking their level of agreement with two statements: “I consider myself a born-again Christian” and “I consider myself an evangelical Christian.” Agreement with either statement qualified a person for the survey, in which respondents were given the standard ANES Bible item but were then presented with a series of follow-up questions tapping different hermeneutical dimensions. Investigating attitudes among evangelicals is important because evangelicals hold a high view of the Bible and are typically more literal in their interpretation. If the existing survey items results in measurement error among evangelicals, then this signals broader trouble for the veracity of the measures. As such, most of our analyses in this paper will draw upon this unique data set.

In a second study, conducted in December 2015, we used a national sample from SSI (not limited to evangelicals) to again compare our new items with the standard ANES Bible question. This sample was balanced for region, age, and gender to align with Census benchmarks for the US adult population. Paired together, these studies allow us to assess public opinion of the Bible among both evangelicals and a broad, national sample of the population.

Our analytical strategy to assess the validity of the standard views of the Bible item involved asking respondents to answer the ANES Bible question and then asking separately about the extent to which respondents agree with statements about how they might interpret a Bible passage. This strategy allows us to gage the extent to which the way people are classified by the ANES item aligns with what people say about how they actually approach biblical interpretation.

Respondents were first asked the views of the Bible question from the ANES. The percentage giving each response is shown in brackets. Not surprisingly, the sample of evangelical Protestants overwhelmingly selected one of the first two options.Footnote 2

Which of these statements comes closest to describing your feelings about the Bible?

• The Bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word. [49%]

• The Bible is the word of God but not everything in it should be taken literally, word for word. [44%]

• The Bible is a book written by men and is not the word of God. [3%]

• Don't know/No opinion [4%]

Respondents were then presented the following prompt:

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements about trying to figure out the meaning of a Bible passage:

1. I rely on the plain meaning of the text.

2. I look for literary devices such as metaphor and allegory which may alter the literal meaning.

3. I read the whole text as truth applying to my life and our time, not limited to the historical context when it was written.

4. I understand that error may be mixed with truth.

The above statements were shown in a matrix with these five response options for each: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree.

The first two statements probably come the closest to tapping what many scholars have in mind when they use the term “literal interpretation.” A “literalist” would agree with statement 1—relying on plain meaning—but would not agree with statement 2—looking for figurative language. Statement 3 addresses the possibility noted above that some respondents may interpret phrases like “actual Word of God” or “literally, word for word” as indicative of the importance and/or relevance of the Bible in daily life. Such a respondent may choose the “literal” option in the standard ANES item because they think the Bible is true and applicable, but with little or no regard to the issues addressed in statements 1 and 2 regarding textual interpretation. Finally, statement 4 introduces the dimension of biblical “inerrancy” discussed in previous research as being conceptually distinct from literalism. As noted above, studies examining the distinction between literalism and inerrancy found mixed results. However, it is important to note that much of the evidence came from split ballot comparisons of two versions of a question. In contrast, our design allows us to compare responses to the standard item and our new items for the same set of respondents. And, the Likert format of our new items allows for greater nuance than the three-category item. A respondent can feel strongly about inerrancy but less strongly about textual approaches, or vice versa.

Analysis

New measures versus the standard item: assessing classification accuracy

Table 1 shows the distribution of responses to the Bible items in our survey of evangelicals. About two-thirds of respondents agreed with the idea of “reading the whole text as truth applying to my life and our time.” A majority (57%) agreed with relying on the text's “plain meaning” but a slim majority (51%) also agreed with the notion of looking for “literary devices such as metaphor and allegory which may alter the literal meaning.” The statement receiving the least agreement was “I understand that error may be mixed with truth,” with 43% agreeing. Responses to the agree/disagree items are correlated with responses to the ANES Bible item, and the differences across columns two and three of Table 1 are statistically significant. However, this association is far from perfect and reveals some interesting patterns. For example, among those choosing the “literal, word for word” option in the ANES item, 41% reported looking for figurative language that might alter the literal meaning of the biblical text. Among those choosing the “not taken literally” option in the ANES item, there are still 40% who agreed with relying on the plain meaning of a text. Although larger percentages of the “not taken literally” group agreed that error may be present in the text compared to those who chose the “literal, word for word” option (55 vs. 29%), this still means that almost three in ten “literalists” agreed with the view that there is error in the Bible. And fully a quarter of “literalists” did not agree with the interpretive approach that relies on the text's “plain meaning.” This is quite an assortment of results that raises concerns about what the standard ANES item is actually tapping, and would seem to call into question using the standard Bible item as the primary measure of religious fundamentalism.

Table 1. Evangelicals' approaches to biblical interpretation by standard views of the Bible item

Entries are column percentages.

Source: 2015 SSI Survey of evangelicals conducted by the authors.

Another interesting finding in Table 1 is the large disparity in the proportion agreeing with the view that a Bible passage should be interpreted as “applying to my life and our time.” There is a 34-percentage-point gap between those answering the ANES item with “literally, word for word” (84%) and those answering, “not taken literally” (50%). This pattern is consistent with the idea that some respondents are viewing the ANES standard item as asking about the contemporary relevance of the Bible and are choosing the first option because of this, not necessarily because of hermeneutical considerations.

Table 2 presents another cut at the data by using responses to the four agree/disagree items to assess how confident we can be about the classification of respondents using the ANES item. The table shows a count of the number of responses out of four that agree with the position most consistent with a “literalist” viewpoint. A respondent who agreed with reliance on plain meaning of the text, did not agree with looking for figurative language, agreed that the Bible's truth applies to our current time, and did not agree that error is mixed with truth in the text would score 4 out of 4. About 10% of the sample displayed this type of consistency, while another 19% scored 3 out of 4. The median number of “literalist” responses was 2 out of 4 (as was the mode), with a mean score of 1.84 (s = 1.19). A respondent with a score of 3 or 4 would seem to be reasonably classified by the “literal” option; this is indicated in green font in Table 2. Similarly, a respondent with 0 or 1 literalist responses would seem to belong outside the “literal” category. The blue font in Table 2 indicates those cases for which classification is ambiguous: those with 2 of 4 responses in the literalist direction. The cells in red font indicate scenarios where the responses to the agree/disagree items about biblical interpretation do not jibe with the answers given to the ANES item. In all, 14% of the sample appears to be misclassified, with another 33% ambiguous. This suggests a non-trivial level of measurement error in the standard Bible item.

Table 2. Extent of literalist interpretation among evangelicals by standard views of Bible item

Entries are total percentages. Total does not add to 100% due to rounding.

Source: 2015 SSI Survey of evangelicals conducted by the authors.

Moreover, the ambiguous and incorrect classifications are not evenly spread across the sample. Those who answered that the Bible is not the word of God were generally classified more accurately than others. Of the “not the word of God” group, fully 82% had responses to the new agree/disagree items that confirmed their classification, while just under 4% were misclassified and 15% remained ambiguous. Of those who chose the “not to be taken literally” option in the ANES item, 60% appeared to be classified correctly, with 29% ambiguous and 11% misclassified. Among those who chose the “literal, word for word” option, 47% appeared to be correctly classified, 36% ambiguous, and 16% misclassified.

Figure 1 also shows the differences in classification accuracy across two other variables: respondent's race and the amount of guidance the respondent receives from religion in his or her life. Among those who reported receiving limited guidance from religion (none or some), 65% were classified correctly, 28% ambiguous, and 7% misclassified. In contrast, of those who reported “quite a bit” or “a great deal” of guidance from religion, just 52% were classified correctly, with 34% ambiguous and 15% misclassified. A sizable gap was also found between white and non-white respondents. Among whites, 56% were correctly classified by the ANES item, while 12% were misclassified and 31% were ambiguous. But among non-whites, 46% were correctly classified, 18% were misclassified, and 37% had ambiguous classifications.Footnote 3 These findings further support the idea that some respondents answer the ANES Bible question with “literal, word for word” as an indicator of religiosity in general (i.e., expressive religiosity), rather than as a question about specific hermeneutical approaches or doctrinal positions.

Figure 1. Measurement accuracy of standard Bible item by respondent characteristics.

Source: 2015 SSI Survey of evangelicals conducted by the authors.

Determinants of “literal” responses

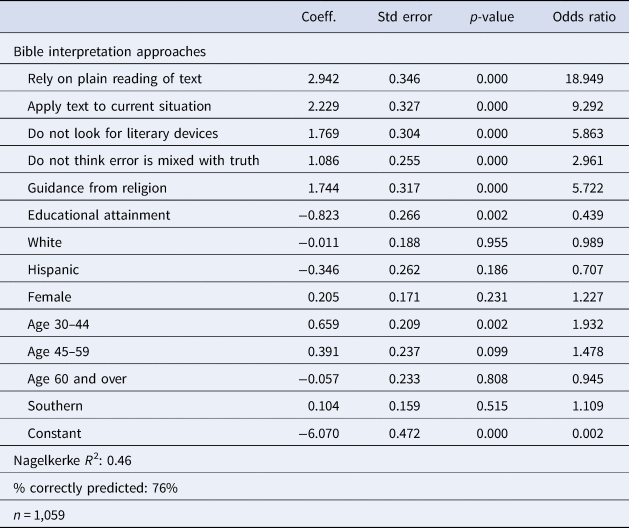

The next step in our analysis is to assess the determinants of a literalist response to the ANES item in a multivariate model that controls for possible influences beyond those bivariate correlates we have discussed thus far. Table 3 presents such a model. The dependent variable is coded 1 if the respondent chose the first option of “literal, word for word” and 0 if she chose either of the other two options. The independent variables include our four agree/disagree items measuring interpretive approaches, as well as controls for the following: guidance from religion, educational attainment, race, Hispanic ethnicity, sex, age, and southern residence. All variables have been rescaled to range from 0 to 1 to facilitate interpretation of the coefficients (cf. Achen Reference Achen1982). If our four interpretation measures are predictive of a literalist response, this supports the notion that the ANES item is tapping more than just a literal hermeneutical approach. Likewise, if, as we suspect, some respondents view the ANES item as a question about general religious commitment, we should find an influence for religious salience (guidance). We also expect education to be negatively related to literalism, as has been the case in prior studies (Kellstedt and Smidt, Reference Kellstedt, Smidt, Leege and Kellstedt1993; Franzen and Griebel, Reference Franzen and Griebel2013).

Table 3. Logit model of Biblical literalism (standard ANES item)

Source: 2015 SSI Survey of evangelicals conducted by the authors.

The results in Table 3 largely confirm these expectations. Each of the four interpretation measures exerts a statistically and substantively significant influence, even controlling for religious salience and a variety of socio-demographic variables. The variable with the largest effect is the “plain meaning” item, which may be of some reassurance that the ANES item is not tapping something completely afield from a literal interpretation approach. However, it is clearly also related to other attitudes about interpretation. The other interpretive dimensions—applying the text to current times, not looking for figurative language, and not viewing the text as having error—are all significant predictors, with odds ratios ranging from 5 to 9. The religious guidance variable is also strongly predictive, as is educational attainment (in the negative direction). In sum, the results in Table 3 suggest that literal responses to the ANES Bible item are a function of more than just a plain-meaning hermeneutical approach to the text. And given that the ANES item is conflating multiple constructs, it will be important to see how these other dimensions of interpretation are related to political attitudes. We turn to this next, first with bivariate analysis and then with multivariate models.

Relationships to political variables

Table 4 shows cross tabulations of political attitudes by biblical interpretive styles—measured by both the ANES item and our four new items. The political variables include party identification, liberal-conservative ideological self-identification, self-identification with the Tea Party movement, and opinion about two prominent “culture war” issues: gay marriage and abortion. As one would expect from this sample of evangelical Protestants, the majority of respondents identified as Republicans, held conservative ideological positions, and reported conservative views on issues. The ANES item is predictive of political variables but so is each of the other four interpretation variables. What is particularly noteworthy in Table 4 is how strongly the “error mixed with truth” item is related to political attitudes. Among those who rejected the idea that the biblical text contained error, 75% identified as Republicans and 74% as conservatives. This compares to an average of 63% Republican and 59% conservative across the other columns of the table. There are similar patterns on the issues, with just 9% favoring legalizing same-sex marriage and 10% supporting abortion being legal in all cases. These results provide further support for the argument advanced earlier that the standard ANES item conflates inerrancy with interpretive approach, and suggest strongly that having distinct measures of these concepts is useful in understanding political attitudes.

Table 4. Evangelicals’ political attitudes by biblical interpretation styles

Source: 2015 SSI Survey of evangelicals conducted by the authors.

Do these bivariate relationships persist in the presence of multivariate controls? By and large, they do. Table 5 presents three multiple regression models of liberal-conservative ideological self-identification. Each model employs the same set of independent variables, with the exception of the measures of biblical interpretation that are included. As in Table 3, all independent variables have been rescaled to range from 0 to 1 to facilitate interpretation of the coefficients. Model 1 has the ANES Bible item only; Model 2 adds our four now-familiar measures of approaches to biblical interpretation; and Model 3 drops the ANES item and relies only on the four new items. Each model includes controls for religious salience, educational attainment, race, ethnicity, sex, age, and region of residence. This modeling approach allows us to compare the effectiveness of the nested models to see whether the standard ANES item is “needed” in the model to explain additional variance, and likewise if the four additional measures provide marginal benefit in explanatory power. We have already established that responses to the ANES item are influenced by multiple considerations, including overall religious salience and the interpretive dimensions tapped with our four new agree/disagree items. Now we investigate the extent to which the ANES item explains variance in political conservatism beyond what can be accounted for by these other variables.

Table 5. Regression models of liberal-conservative ideological self-identification, U.S. evangelicals

Source: 2015 SSI Survey of evangelicals conducted by the authors.

We set up Model 1 as most religion and politics scholars have done: the ANES three category item is the sole indicator of how the respondent views the Bible. And Model 1 has an unsurprising set of results: the ANES views of the Bible item are associated with political conservatism. However, we would expect that the influence exerted by the ANES Bible item will diminish when the other biblical interpretation variables are included in the model. This expectation is supported by the results in Model 2. When our four biblical interpretation measures are added to the model, the effect of the standard ANES variable is no longer statistically significant. Two of the four new variables are statistically significant predictors: relying on the plain meaning of the text and disagreeing that error is mixed with truth in the text. The most powerful predictor in the model is the item measuring views about error in the Bible. Moving from strong agreement to strong disagreement about error being “mixed with truth” in the biblical text accounts for a change of 1.4 points on a 7-point liberal/conservative ideology scale.

The addition of our four interpretive variables to Model 2 significantly improves the model fit, yielding a 47% increase in the adjusted R 2 (from 0.17 to 0.25). The F-tests confirm the model's improvement, and also confirm that Model 3, which lacks the standard ANES item, performs just as well as Model 2. The results for the other independent variables are fairly consistent across the three models, with statistically significant effects for guidance from religion, white racial identification, and age 60 or older. In summary, the findings demonstrate that including more indicators of biblical views beyond the ANES Bible item can pay sizable dividends in terms of explaining variance in political attitudes.Footnote 4

Do these findings apply to more than just evangelicals?

As interesting as the findings thus far may be, they have been confined to our survey of evangelicals. Some readers are no doubt wondering if these relationships hold for Americans beyond the evangelical camp. To address this, we turn in the final section of the analysis to examine data from a second online survey from December 2015 that employed a national adult sample from SSI. The analytical strategy is straightforward: to the extent possible with the data, we estimate the same models used in Table 5. The variables used are identical with two exceptions. First, because the sample was not limited to evangelicals, we add controls for religious tradition. The analysis in Table 6 includes dummy variables for evangelical Protestants, Catholics, African American Protestants, Jews, the religiously unaffiliated, and a catch-all category of other small traditions, with mainline Protestants serving as the excluded reference category. Second, due to time constraints on the survey (which was designed primarily for another research project) only two of our four interpretation measures were asked on the questionnaire. We include these two, the “plain meaning” and “error mixed with truth” items.

Table 6. Regression models of liberal-conservative ideological self-identification, U.S. adults

In Table 6 we see that the results for a national sample have very similar patterns to those observed above in Table 5 when the analysis was confined to evangelicals. As before, Model 1 has the ANES Bible item as the sole belief measure, and the result is a statistically significant coefficient. However, when the “plain meaning” and “error mixed with truth” variables are added to the equation in Model 2, we find the influence of the ANES Bible variable diminished to the point of being statistically indistinguishable from zero. Just as was the case for the models in Table 5, the results in Table 6 demonstrate the importance of conceptualizing and measuring views about error in the Bible separately from measuring literal interpretation. The “error” variable is once again the most potent predictor in the models of political conservatism. It is also interesting to note the predictive power of the religion variables compared to other socio-demographic variables. Other than age, religious characteristics are the only consistent predictors of conservatism in these models. And of the religion variables, our two new measures stand out as the most influential.

Conclusion

In this paper we sought to present a more nuanced understanding of how views of the Bible affect political attitudes, and to offer practical guidance for social scientists to measure religious beliefs. We found considerable evidence that the standard Bible item, used widely in many surveys, results in significant measurement error. New agree/disagree items revealed that multiple hermeneutical dimensions are being conflated by the standard ANES item. Approximately 14% of respondents were misclassified by the ANES item, with another 33% having an ambiguous classification.

In addition to clarifying aspects of biblical interpretation, our new survey items were also successful at predicting political attitudes. When the four new items were included in a multiple regression model along with the ANES Bible item, the standard ANES question dropped out as a significant predictor of political conservatism. This result held not only for a sample of evangelicals, but also for a national sample of adults that included a representative array of religious affiliations and viewpoints.

Of the interpretive dimensions measured, views about whether the Bible contains error were the most strongly related to political attitudes. We highly recommend the use of the “error mixed with truth” item in future studies. We further recommend that researchers avoid using just one single indicator to measure views of the Bible. Our findings show that inerrancy is indeed distinct from literalism both conceptually and empirically. We also found it useful to allow respondents to express a range of agreement or disagreement about interpretive approaches rather than trying to shoehorn respondents into one of just three categories.

Although we expanded the range of hermeneutic dimensions measured in surveys, we do not claim to have covered every possible interpretive approach. There is certainly ample room for further research to expand into other aspects of how people view and interact with the Bible. For example, future research might examine how our new biblical interpretation measures relate to other “worldview” variables such as Christian nationalism (Whitehead and Perry, Reference Whitehead and Perry2020), authority-mindedness (Wald et al., Reference Wald, Hill, Owen and Jelen1989; Mockabee, Reference Mockabee2007), or preference for absolutist versus consequentialist rhetoric (Marietta, Reference Marietta2008). We also acknowledge the limitations of studying religious beliefs with closed-ended survey items that may not yield comparable meanings across religious traditions with different norms (Mockabee et al., Reference Mockabee, Monson and Tobin Grant2001). As Friesen and Wagner (Reference Friesen and Wagner2012) have shown, qualitative data can be a useful supplement to closed-ended survey questions about religious beliefs and behaviors. Thus, an open-ended follow-up question could shed more light on what survey respondents mean when they answer the standard Bible item.Footnote 5 Finally, our data come from cross-sectional surveys in a single year; it would be beneficial to continue to collect data using these new measures over time. These caveats notwithstanding, we think the general implication is clear: scholars who want to study religious belief in the U.S. need to move beyond the standard, double-barreled Bible items. Gathering more nuanced data on the public's views of the Bible will better equip scholars to improve the accuracy of their investigations of the relationship between religious belief and public life, as well as assess future changes in the American religious landscape.

Stephen T. Mockabee is associate professor in the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Cincinnati, where he directs the Graduate Certificate in Public Opinion & Survey Research.

Andrew R. Lewis is associate professor in the School of Public & International Affairs at the University of Cincinnati, where he researches politics, law, and religion in the U.S.