A perplexing problem about China’s Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (CMS)

China’s CMS, popular in the 1960s and 1970s for its widespread benefits to farmers in rural China, was highly praised by the World Bank and World Health Organization (WHO). The scheme was considered an unprecedented example of a successful health care model in a low-income, developing country. However, the CMS almost collapsed in the 1980s (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Ling, Shen, Lane and Hu1989; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hu and Lin1993; White, Reference White1998). Although the central government of China has worked actively to reconstruct the CMS, renaming it the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS), the NCMS has achieved only some of its goals, and provided farmers limited financial protection (Green, Reference Green2004; Yip and Hsiao, Reference Yip and Hsiao2009; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cheng, Tolhurst, Tang and Liu2010; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Gao and Rizzo2011; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Guo, Jin, Peng and Zhang2012; Yang, Reference Yang2013).

To date, the vast majority of research on the NCMS has considered it as a type of health insurance for farmers (Anson and Sun, Reference Anson and Sun2004; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Guo, Jin, Peng and Zhang2012). However, two questions arise if the CMS was really just an insurance system. First, why was the CMS so successful in the poor and underdeveloped China of the pre-economic reform era? Second, why was it so difficult to reconstruct a similar insurance system model in the rich and rapidly developing China of the 21st century? In fact, based on the historical origin and main activities of the CMS (China’s Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme Act (draft), 1979; Liu, Reference Liu2008), it likely functioned as a health cooperative rather than a health insurance system.

The CMS as a type of health cooperative

The CMS was internationally famous in the 1970s as a community-based cooperative health system. At the 1978 Alma Ata conference, China’s experience of the CMS was praised as an holistic primary health care system, not just a health insurance system (Sidel, Reference Sidel1972a, Reference Sidel1972b; Sidel and Sidel, Reference Sidel and Sidel1982). However, during the 1980s and 1990s, the international literature came to regard the CMS as a type of health insurance (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Ling, Shen, Lane and Hu1989; Shi, Reference Shi1993; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Tang, Bloom, Segall and Gu1995), and almost all international papers written in the last two decades have regarded the CMS as a rural insurance system.

To the best of our knowledge, most international scholars are only familiar with the CMS in the new China, namely the post-liberation period after 1949. However, the CMS already existed in pre-liberation rural China. According to Liu (Reference Liu2008), a scholar of the rural social history of modern China, the origin of the CMS can be traced back to rural cooperative movements in northern China in the 1920s. Especially important was the China Huayang Disaster Relief Cooperative (1923–1929), which was followed by the China Commonalty Education Promotion Association of Dingxian County, Hubei (1929–1937). Later came a pilot scheme of the CMS implemented in certain regions, including Xiaoyuanli Village, Huibei District, Wuxi, Jiangsu (1936–1937), and this scheme was followed by the health cooperative in Shan-gan-ning District, northwest China (1938–1946). In Liu’s view, the core of the CMS was ‘health care provided through cooperation’. As an example, the China Huayang Disaster Relief Cooperative was a charitable organization self-organized by local farmers with a branch named the Department of Drugs. The cooperative regularly organized its members to check community and family health, sweep streets and collect litter, and provided smallpox vaccinations in the spring. The Department of Drugs was funded from the public accumulation fund of the China Huayang Disaster Relief Cooperative. The cooperative stipulated that ‘both members and non-members as well as villagers, including neighbouring villagers, will have their every request granted and shall not be charged’, indicating that the emphasis was on providing free health care. According to Liu, the CMS collapsed due to the invasion of China by Japan (1931–1945). In addition, as in the pre-liberation period, Mao Zedong, the first Chairman of the New China, pointed out that ‘Cooperativization is the only way for to realize the liberation of the poor and the only way for the poor to become rich’ (Yan, Reference Yan2007; Wang, Reference Wang2008). Although this statement was intended to be a general reference to social issues, it was also considered an embodiment (or deduced result) of Mao Zedong’s thoughts on health. Many researchers interested in China agreed with the conclusion: ‘If there were no cooperative movements in rural areas, there would be no CMS in China’ (Horn, Reference Horn1972; Yan, Reference Yan2007; Wang, Reference Wang2008). In contrast, no researchers agreed with the alternative statement: ‘if there was no insurance in rural areas, there would be no CMS in China’. Both before and after the founding of the new China, the CMS was considered to be derived not from an insurance system, but rather from a cooperative system.

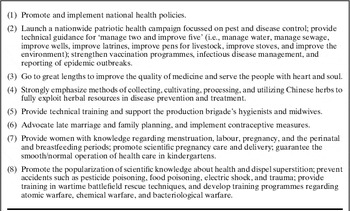

Conversely, to our knowledge, China’s Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme Act (draft), promulgated by the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China on 15 December 1979, was the earliest government declaration on the CMS (China’s Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme Act (draft), 1979). The Act can be considered the most authoritative source for the missions/main activities of the CMS, and its content is as shown in Box 1.

Box 1 The missions/main activities of the CMS

Source: China’s Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme Act (draft) (1979)

According to the Acts, the CMS was mainly organized at the level of administrative villages, each of which generally included about 10 natural villages. At that time in China, and even now, the population of an administrative village was generally about 2000 people, and rarely exceeded 5000 people. Obviously, there are barriers to effectiveness for a health insurance system with participation of only about 2000 members. However, the CMS was very effective and was praised by the World Bank and WHO. In addition, it is worth noting the role of the ‘barefoot doctors’ in the CMS. The name ‘barefoot doctors’ was a vivid and formal description of their work pattern, specifically that they would remove their shoes and socks (i.e., go barefoot) and go into the paddy fields to work and live together with farmers (Sidel, Reference Sidel1972a, Reference Sidel1972b; White, Reference White1998). This work pattern could involve cooperation between health workers and farmers or among those in need of health care, agricultural work and participating in the farmers’ way of life, and such cooperation could also include innovative behaviour. Barefoot doctors could use their unique work pattern to directly and closely observe, analyse, and treat health-related risk factors in farmers’ working and living context (Horn, Reference Horn1972; Sidel, Reference Sidel1972a, Reference Sidel1972b; China’s Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme Act (draft), 1979; White, Reference White1998; Yan, Reference Yan2007; Wang, Reference Wang2008). In so doing, they had the opportunity to provide timely disease surveillance, early warning detection, and early intervention in addition to regular health care, all of which functions were unrelated to health insurance. In addition, although the importance of cooperative institutions for the CMS has always been stressed, but perhaps an equally important phenomenon of the CMS has been ignored. This phenomenon is cooperative behaviour involving health workers and farmers, or balancing the needs of health care, agricultural work, and farmers’ way of life in targeting health-related risk factors. This is a phenomenon that existed in both the historical origin and main activities of the CMS. The ‘cooperative’ element of the CMS proposed here includes the two aspects of cooperative institutions and cooperative behaviour.

In theory, the CMS embodies a collaborative approach to health affairs, together with the advantages it entails. Standing alone, the medical care delivery section or disease control and prevention section cannot effectively address the burden of disease and illness in a population. Instead, to effectively address this, broader cross-sector collaboration is considered essential (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Weiner, Metzger, Shortell, Bazzoli, Hasnain-Wynia, Sofaer and Conrad2003; Nicola, Reference Nicola2005). The literature considers collaborative advantage, mostly focussing on the elements of collaboration, such as vision and mission, action planning, leadership, and resources for mobilization. However, the next essential question is how to create collaborative advantage (Fawcett et al., Reference Fawcett, Francisco, Paine-Andrews and Schultz2000; Dowling et al., Reference Dowling, Powell and Glendinning2004). In this regard, the CMS may provide an operational mechanism for creating a collaborative advantage that incorporates the following two aspects. The first aspect is a mechanism of internal elements, namely the parties involved in cooperation (cooperation between the health sector and the working and living sector), as well as the specific details of cooperation (direct and close observation, analysis, and treating health-related risk factors in farmers’ working and living context). The second aspect is a mechanism of external elements, namely voluntary collaboration between internal elements combined with external policy support and advocacy. According to China’s Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme Act (1979 draft), the CMS receives no financial support from central or local government.

A preliminary analysis on the reconstruction of the CMS

The CMS-related literature of the past 20 years has almost universally regarded the reconstruction of the CMS (namely the NCMS) as a health insurance system intended to serve rural areas, and the payment of premiums has been taken to represent farmers’ enrolment in the NCMS (Anson and Sun, Reference Anson and Sun2004; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Gu and Dupre2008; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cheng, Tolhurst, Tang and Liu2010; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Jiang, Zhao, Tao, Ling and Cherry2011; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Guo, Jin, Peng and Zhang2012; Yang, Reference Yang2013). In the case of the NCMS, enormous misunderstanding or bias would result from a lack of awareness of the cooperative behaviour mentioned above. Such misunderstanding or bias can provide a useful clue for explaining the perplexing problem described above: namely how to account for the success of the CMS success in pre-economic reform China, and for its lack of success in 21st century China.

Although many studies have shown that the NCMS has a coverage rate superior to that of the CMS, as well as increased outpatient and inpatient utilization, the NCMS nevertheless provides limited financial protection and fails to relieve the economic burden from disease experienced by farmers (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Cheng, Tolhurst, Tang and Liu2010; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Jiang, Zhao, Tao, Ling and Cherry2011; Yang, Reference Yang2013). Some researchers reported that government investment in public health and primary care was considered unsustainable (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Gusmano and Cao2011). In some poor areas, the government is the exclusive sponsor of the NCMS (which essentially resembles health insurance) (Xu and Tan, Reference Xu and Tan2002; Fu, Reference Fu2011; Yang, Reference Yang2011), meaning the NCMS becomes a government-run ‘one-man show’. Perhaps such a situation is unsurprising given that China remains a developing country with the largest agricultural population in the world. However, the fundamental transformation of China’s political and economic institutions means that a complete return to the CMS of the pre-economic reform era may be very difficult. Nevertheless, it is possible to promote cooperation between health workers and farmers or between health care provision and agricultural work, together with awareness of the farmers’ way of life. Such cooperation would target health-related risk factors, or function as a holistic primary health care system as proposed at the 1978 Alma Ata conference. As a developing country, rural China needs health insurance, but perhaps needs the CMS even more.

There is a further problem related to the CMS that deserves attention. Although the CMS in China was a product of the last century, health co-operatives are neither an old measure (in fact they are newer than health insurance) nor an outdated, dilapidated approach (Nayar and Razum, Reference Nayar and Razum2003; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Redford, Poe, Veach, Hines and Beachler2003; Scutchfield, Reference Scutchfield2009). According to the International Health Cooperative Organization, health co-operatives currently serve at least 100 million households worldwide, in various countries, including Canada, the United States, India, Japan, Benin, Mali, and Uganda, and efforts are underway to include health co-operatives in current health care reform in the United States. Health co-operatives have different forms, including worker-owned organizations, consumer-owned organizations, jointly owned organizations (with ownership shared among consumers, workers, and communities), and purchasing or shared service co-operatives (Nayar and Razum, Reference Nayar and Razum2003; McLean and Sutton, Reference McLean and Sutton2008; International Health Co-operative Organization 2013). Although the past 20 years have seen negative experiences related to the development of health co-operatives, there is renewed interest in their revival in both developing and developed countries (Grembowski et al., Reference Grembowski, Anderson, Conrad, Fishman, Larson, Martin, Ralston, Carrell and Hecht2008; McLean and Sutton, Reference McLean and Sutton2008; Ralston et al., Reference Ralston, Martin, Anderson, Fishman, Conrad, Larson and Grembowski2009). In other words, although the CMS collapsed in China, similar schemes are flourishing elsewhere in the world. In the future, in-depth analysis of these schemes is required, with a special focus in ethnographic research on the elements of collaboration and cooperative relationships, cooperative behaviour and health risk factors and health outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank National Natural Science Foundation of China for funding this study. The authors acknowledge the valuable comments of the anonymous PHCRD reviewer.

Financial Support

This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 71273098). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exist.