The question of whether individual language users modify their internalized grammatical system during adulthood is one that has long divided linguists of different theoretical persuasions. On the one hand, usage-based models of language tend to consider language as an inherently “adaptive” system that is in a constant state of change, both at the individual and the community level (Diessel, Reference Diessel2019). In such models, the linguistic behavior of individuals is considered to be based on the rules they have inducted from “the frequency of the different expressions and constructions encountered by the speaker” during the past social interactions they have had with other individuals (Barlow, Reference Barlow2013:444; also see Beckner, Blythe, Bybee, Christiansen, Croft, Ellis, Holland, Ke, Larsen-Freeman, & Schoenemann, Reference Beckner, Blythe, Bybee, Christiansen, Croft, Ellis, Holland, Ke, Larsen-Freeman and Schoenemann2009:14). Importantly, these utterance production rules inducted from language use are, essentially, never entirely fixed and can be affected by every new instance of language use the individual encounters (Bybee, Reference Bybee2006). Thus, the idea that an individual's internalized grammar is susceptible to change lies at the core of the utterance-based (Croft, Reference Croft2000:45-55) or usage-based model, in which the “current and past interactions [of individual language users] together feed forward into [their] future behavior” (Beckner et al., Reference Beckner, Blythe, Bybee, Christiansen, Croft, Ellis, Holland, Ke, Larsen-Freeman and Schoenemann2009:2).

On the other hand, there are various theoretical models of language where grammar, at least at the level of the individual speaker, is conceived as a relatively fixed system. Such models are often (but not exclusively) characterized by a more modular or componential view of language, wherein the linguistic knowledge of individuals comprises a lexicon and a separate rule system (or “grammar”) that generates the syntactic patterns in which lexical items can be inserted. With respect to the possibility of language change across the individual's lifespan then, it is generally held that modifications in the lexicon are not restricted by age (Kerswill, Reference Kerswill1996; Meisel, Elsig, & Rinke, Reference Meisel, Elsig and Rinke2013:26). By contrast, more “systemic changes” that affect the rule system that generates grammatical sentences, “only take place in the process of the transmission and incrementation of a change, that is, during childhood” (Meisel et al., Reference Meisel, Elsig and Rinke2013:37), when the grammatical system is imperfectly transmitted from parent to child (for recent proponents, see Anderson [Reference Anderson2016], Lightfoot [Reference Lightfoot2019]). Systemic (e.g., morphosyntactic) change through time is thus conceptualized as “merely a function of changes in the population, with older speakers becoming inactive and dying, and younger speakers continually entering the community” (Denison, Reference Denison and Hickey2002:61). Such models of language change, which have been proposed since at least the late nineteenth century (López-Couso, Reference López-Couso, Hundt, Mollin and Pfenninger2017:339), conceptualize grammatical change as being child-based (or, at least, child-centered) rather than utterance-based.

At the same time, the two types of models are not always at odds. Both the utterance-based model and current versions of the child-based model would, for instance, accept that it is possible for adults to participate in lexical or so-called “surface structure changes,” such as the replacement of the Early Modern English third-person suffix -(e)th by -(e)s (Raumolin-Brunberg, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg2005), or cases of competition between different pronominal forms (e.g., Raumolin-Brunberg, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Nevala and Palander-Collin2009). Furthermore, there is also consensus on the idea that, in cases of competition between mutually exclusive structural properties that relate to different grammars generating them (e.g., presence or absence of do-support in different clause types [e.g., Raumolin-Brunberg, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Nevala and Palander-Collin2009]), adults freely (and frequently) change the rate by which they use either the old or the new system. In a wide range of studies, it has been shown that “adult frequencies of linguistic forms are labile” (Tagliamonte & D'Arcy, Reference Tagliamonte and D'Arcy2007:213; in reference to Labov, Reference Labov2001:447), empirically confirming that the language of adults, including the frequency with which they employ one morphosyntactic “rule” over another (or others), is not fixed in quantitative terms (Bergs, Reference Bergs2005; Buchstaller, Reference Buchstaller2015, Reference Buchstaller2016; Nahkola & Saanilahti, Reference Nahkola and Saanilahti2004; Neels, Reference Neels2020; Raumolin-Brunberg, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg2005, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Nevala and Palander-Collin2009; Raumolin-Brunberg & Nurmi, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Narrog and Heine2011; Sharma, Bresnan, & Deo, Reference Sharma, Bresnan, Deo, Cooper and Kempson2008).

Having established that the grammar of adults can and does change in quantitative terms, the focus of the discussion on adult lifespan change has subsequently shifted to the question of whether adult grammar can also be altered in “qualitative terms.” Notably, it has proven much more difficult to attest instances of what is termed “core” grammatical change, which would involve a more or less radical change “from one invariable and uniform grammatical system to another” (Meisel et al., Reference Meisel, Elsig and Rinke2013:30) in adulthood (also see the comments in Raumolin-Brunberg [Reference Raumolin-Brunberg2005:47], [Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Nevala and Palander-Collin2009:192]). Within the variationist tradition, such radical categorical changes have, to our knowledge, not yet been documented. However, some studies have reported on partial categorical or “inventory” changes (Buchstaller, Krause-Lerche, & Mechler, Reference Buchstaller, Krause-Lerche, Mechler, Beaman and Buchstaller2021), where a novel form is introduced or is used in a novel way (or an older form or usage ceases to be used). Petré and Van de Velde (Reference Petré and Van de Velde2018) and Anthonissen and Petré (Reference Anthonissen and Petré2019) found that novel, grammaticalized uses of infinitive be going to are (to a limited extent) adopted in adulthood by speakers who previously only had the lexical use of infinitive be going to in their repertoire. Furthermore, adults may adopt uses that are more advanced on the grammaticalization scale than those in their repertoire, which may signal that usage constraints of grammatical patterns change qualitatively across the lifespan. A recent example includes the constraint change and inventory change in, among other variables, individuals’ systems of quotation reported in Buchstaller et al.'s (Reference Buchstaller, Krause-Lerche, Mechler, Beaman and Buchstaller2021) panel study. Such findings seem to call for amendment of the conclusions by Tagliamonte and D'Arcy (Reference Tagliamonte and D'Arcy2007:210), who observe changes in the constraints on the use of be like between generations, but not within generations.

The aim of this paper is to further contribute to the ongoing debate on morphosyntactic lifespan change, defined here as observable intraindividual shifts in the grammatical choices individuals make between functionally equivalent (or competing) structures. We focus on an ongoing change involving two types of ing-nominals in seventeenth-century English, using statistical model comparison.

Our first hypothesis is defined simply to corroborate earlier findings on frequency-based change, which state that when a competition-driven syntactic change is taking place in a linguistic community, individuals in that community will change the frequency or rate by which they use the competing syntactic structures across their lifespan (Raumolin-Brunberg, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg2005, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Nevala and Palander-Collin2009). Furthermore, based on earlier studies, we hypothesize that these changes in frequency will predominantly proceed in the direction of the ongoing change in the rest of the community (Anthonissen, Reference Anthonissen2020:325; Baxter & Croft, Reference Baxter and Croft2016:156; Raumolin-Brunberg, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Nevala and Palander-Collin2009:170).

A second hypothesis is formulated to assess how gradual contextual diffusion, through which syntactic changes often proceed at the community level, recurs in the linguistic behavior of individuals. Population-level studies have amply demonstrated that innovative grammatical structures tend to diffuse gradually from one grammatical context to another (e.g., Kroch, Reference Kroch1989; Rutten & van der Wal, Reference Rutten, van der Wal, Boogaert, Colleman and Rutten2014; Smirnova, Reference Smirnova, Barđdal, Smirnova, Sommerer and Gildea2015; Tagliamonte & Denis, Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2016; Traugott & Trousdale, Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013). Innovative variants tend to emerge in specific contexts and only after they become sufficiently frequent or entrenched in those contexts do they “spark off the innovations that constitute the following stage” (De Smet, Reference De Smet2016:100). Studies that consider such stepwise patterns of diffusion at the level of the individual are relatively rare, but it has tentatively been argued that the “innovation-entrenchment-further innovation” trajectory observable in population-level language also exists “in patterns of variation across individual speakers” (De Smet, Reference De Smet2016:100). By examining the frequency by which individuals adopt innovative variants in different grammatical contexts, we can help determine the extent to which this hypothesis holds true and whether the rate with which the variants occur in these contexts is comparable across individuals.

A third hypothesis we assess is that adults can participate in the diffusion of the new variant to new grammatical contexts and reach a more advanced stage of the development occurring at the community level (for similar endeavors, see Anthonissen & Petré, Reference Anthonissen and Petré2019; Buchstaller et al., Reference Buchstaller, Krause-Lerche, Mechler, Beaman and Buchstaller2021; De Smet, Reference De Smet2016; Mackenzie, Reference MacKenzie2019; Tagliamonte & D'Arcy, Reference Tagliamonte and D'Arcy2007:213). In investigating this hypothesis with real-time data, we provide some tentative (and relatively rare, see Mackenzie [Reference MacKenzie2019:17]) support for the idea that the grammar of adults may be susceptible to qualitative lifespan change if qualitative lifespan change is defined as changes in the grammatical contexts or constraints under which competing morphosyntactic constructions are used by each individual across their lifespan.

Data and method

Early Modern English ing-nominals

The case study chosen to address the issues at hand is the diachronically unstable variation between two types of English ing-nominals, illustrated in (1) and (2):

(1) Idolatry consists in giving of that worship which is due to God, to that which is not God. (EMMA, Daniel Whitby, 1674)

(2) … the greatest part of Leviticus is imploy'd in giving Laws concerning Sacrifices (EMMA, Daniel Whitby, 1697)

The two types of ing-nominals in (1) and (2) exemplify a well-known case of morphosyntactic variation in the Early Modern English period, whereby two different syntactic structures can be used largely interchangeably: in both examples, a derivational suffix -ing is attached to a base verb (i.e., give) to create a deverbal noun phrase that behaves much like other, more prototypical English noun phrases. The main difference between the examples in (1) and (2) appears to be that, in example (1), the object of giving occurs as an of-phrase, whereas the structure in (2) does not require an of-phrase. In terms of their contextual distribution in (Early) Modern English, both types of ing-nominal frequently functioned as prepositional complements but also occurred as the direct object or subject of a clause (De Smet, Reference De Smet2008; Fanego, Reference Fanego2004; Houston, Reference Houston, Fasold and Schiffrin1989; Nevalainen, Raumolin-Brunberg, & Manilla, Reference Nevalainen, Ramoulin-Brunberg and Manilla2011).

The distributional overlap between ing-OF and ing-Ø in Modern English can be explained by the fact that the two variants are historically related: the innovative variant, ing-Ø, most likely developed from ing-OF in the Middle English period. As shown by Fanego (Reference Fanego2004), the first instances of ing-Ø were attested around 1250. The subsequent diffusion of the progressive variant ing-Ø proceeded according to what Fanego (Reference Fanego2004:38) has termed a “hierarchy of relative nominality.” First, ing-Ø became a well-established alternative to ing-OF in “bare” contexts, where the ing-form was not preceded by a determiner. Such contexts are illustrated in (3):

[no determiner: bare]

(3) a. The soul can't dye, cannot therefore the Man dye? If not, there is no such thing, as killing of Men, or mortal Men. (1673, PW3)

b. It was a cruel mercy which Tamberlane shewed to three hundred Lepers in killing them to rid them out of their misery (1662, SG2)

It was only after ing-Ø was established in determinerless contexts that it further diffused to contexts with a determiner. Over the course of the Early Modern and Late Modern period, the second stage of diffusion involved a spread to contexts with a determiner that is a possessive, as illustrated in (4).

[possessive pronoun: POSS]

(4) a. But I perswade my selfe, it cannot well be used in the defence of his killing of the Dragon: (1631, Peter Heylyn)

b. then I must believe that his killing my Father was no murder, and that they died wrongfully who were Executed for having a hand in his Death (1680, Roger L'Estrange)

Finally, in the third stage of diffusion, ing-Ø spread further to contexts where the determiner “is an article, usually definite”—illustrated in (5) (Fanego, Reference Fanego2004:38).Footnote 1 At this point, ing-Ø also started appearing following demonstratives—as illustrated in (6a)—and indefinite articles—illustrated in (6b)—albeit to a lesser extent.

[definite article: the]

(5) a. how long thou hast lived to little purpose, yea, to the killing of thy soul for ever (1659, George Swinnock)

b. it was given out, that the killing an Usurper, was always esteemed a commendable Action (1679, Gilbert Burnet)

[demonstrative, indefinite article, quantifier: other]

(6) a. Ninthly, Protest against that most terrible and odious shedding of the innocont blood of those 3 forementioned (1640, William Prynne)

b. thou wert thereby kept from a further shedding the blood of thy soul. (1659, George Swinnock)

Specifying our hypotheses to the diachronically unstable variation between ing-OF and ing-Ø in the seventeenth century, we can reformulate them as follows:

– Hypothesis 1: The proportion of ing-OF and ing-Ø in the linguistic output of individuals changes across their lifespan. These developments can, but need not be, in the direction of the community development (that is, an increase of ing-Ø at the expense of ing-OF).

– Hypothesis 2: There is a determiner constraint hierarchy (bare contexts > possessives > (definite) articles). This hierarchy attested at the community level can also be witnessed in the linguistic output of individuals.

– Hypothesis 3: Changing usage proportions of ing-Ø and ing-OF can occur and vary in extent and direction in different grammatical contexts within and between individuals. Additionally, determiner constraints (and accompanying usage of ing-OF and ing-Ø) can, but need not, be stable across an individual's lifespan.

Early Modern Multiloquent Authors (EMMA) corpus

The data was collected from the corpus of Early Modern Multiloquent Authors (EMMA), the compilation of which has been detailed by Petré, Anthonissen, Budts, Manjavacas, Silva, Standing, and Strik (Reference Petré, Anthonissen, Budts, Manjavacas, Silva, Standing and Strik2019). For the present study, it is important to highlight the following:

– The corpus contains the works of fifty authors born between 1599 and 1686, whose oeuvres comprise at least 500,000 words and are relatively evenly distributed across a long career (average = thirty-eight years). The authors are grouped by birth date in five separate “generations.”

– The authors included in EMMA constitute a relatively homogeneous group, with the majority (thirty-seven authors) being members of London society who spent a considerable time of their active life in London. The remaining thirteen authors are not strongly connected to London society (neither socially nor geographically). The corpus is enriched with metainformation about text type and the authors’ place of birth, social circles, and geographical mobility.

Rather than querying the entire corpus (87,126,198 words) for strings of more than two letters followed by ing (to exclude sing, king, etc.) and manually filtering tokens that did not represent instances of deverbal nominalizations (e.g., evening, something, etc.), we restricted our sample in the following ways:

– To control for genre variation, we restricted querying to texts labeled as descriptive or argumentative prose and letters.

– Our sample is restricted to texts produced by authors from the first three generations in the corpus (born between 1599 and 1644). As a result, the resulting dataset spans across approximately one hundred years (the ”oldest” tokens dating from 1626 and the most recent ones from 1721), during which the progressive variant ing-Ø was steadily on the rise. With respect to the stages of diffusion described by Fanego (Reference Fanego2004), ing-Ø had already been widely adopted in bare contexts. Following Nevalainen et al.'s (Reference Nevalainen, Ramoulin-Brunberg and Manilla2011:7) classification of Labov's (Reference Labov1994) five stages of linguistic change, the development in bare contexts was virtually completed (representing over 85% of all tokens). In possessive contexts, the stage of development can be classified as “mid-range” to “nearing completion” (between 35% and 85%), whereas ing-Ø was “new and vigorous” (15%-35%) in contexts with a (definite) article.

In total, twenty-one authors are included in our sample.Footnote 2 The total number of observations for each author is listed in Table 1.Footnote 3

Table 1. Absolute and relative frequencies of ing-OF and ing-Ø per author

For each of these individuals, the total number of ing-nominals they produced in their prose and letter writing was collected. This totals up to 16,633 tokens, of which 11,862 are examples of ing-Ø (69%) and 4,767 are examples of ing-OF (31%).

Statistical analysis

We fitted a number of different logistic regression models, ranging from a basic model with no independent variables to more complex multilevel models. In the multilevel models, the following variables are included: the author, the age of the author at the time a variant was produced (in order to model lifespan developments), and the determiner that preceded the variant (to model effects of grammatical conditioning). The independent variable “determiner” comprises four levels: bare contexts, possessive contexts, definite article contexts, and other contexts (including demonstratives and indefinite articles). Models will be fitted with varying “author” intercepts or varying “author” slopes. The final, most complex model includes an interaction effect between “age” and “determiner” with varying author slopes.

Bayesian regression models

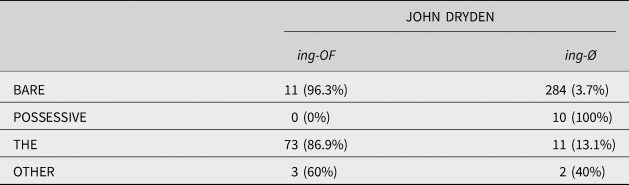

A common problem for logistic mixed-effect models, which, unlike linear models, involve a binary dependent variable, is that there is a fairly high risk of (quasi-)separation problems, which occur when “one predictor completely or almost completely separates the binary response in the observed data” (Kimball, Shantz, Eager, & Roy, Reference Kimball, Shantz, Eager and Roy2019:231). Ideally, when logistic regression is used to model variation, there is at least partial overlap between the dependent variables with respect to all levels of the independent variables. Overlap is demonstrated by the dataset for John Dryden in Table 2, where the levels “bare,” “the,” and “other” include observations for both of the dependent variables. With the level “possessive,” however, John Dryden's data exhibits separation: there are ten ing-nominals preceded by a possessive, which are exclusively of the ing-Ø type. In John Dryden's data, the predictor level “possessive” thus perfectly predicts the dependent variable.

Table 2. Overlap and quasi-separation in the data set

Such (quasi-)separation could be due to the low number of observations for some conditioning factors or because one of the individuals in the dataset truly perfectly separates the dependent variable under particular conditions. Regardless, (quasi-)separation presents an issue for the way in which mixed-effect models (such as glmer) compute the probability of the observed data, as it can cause the estimates for the fixed and random effects to become extremely—even infinitely—large.Footnote 4 In the present case, the problems caused by quasi-separation ultimately led to a failure to converge for glmer.Footnote 5

The present study relies on a Bayesian implementation of binomial logistic regression fitted with brm (R [R Core Team, 2021]; package: brms [Bürkner, Reference Bürkner2017, Reference Bürkner2018]).Footnote 6 The function underlying the models is identical to that of glmer in that the logistic function of the proportion of the binary dependent variable is represented as a linear function of fixed and random effects. However, the way in which the results are computed differs slightly. Bayesian models do not start from the assumption that all possible estimate values of the effects are equally likely. Instead, Bayesian computation allows the analyst to impose expectations (and constraints) on estimate values in the form of priors. Such priors assume the shape of a distribution (normal/Gaussian, Cauchy, etc.) around a mean with a certain standard deviation. They are used to state, for instance, that estimate values for the effects are likely near a given mean and very unlikely to reach the extreme values that may cause failure to converge.

In the present case, the priors for all models are “weakly informative priors”: the expectations that are set still take a wide range of possible outcomes into account but exclude highly unlikely, extreme values that cause convergence issues. The (varying) intercept priors and priors for the fixed effects were set as distributed around a mean of zero (translating into the starting assumption that they have no effect on the choice between ing-OF and ing-Ø), with a standard deviation between one and five.Footnote 7

Model comparison

To demonstrate the procedure, we will start by formulating the basic hypothesis that there is a considerable amount of variation between authors in the extent to which they use ing-Ø. To assess whether this hypothesis holds true, we fit two models. First, we fit a simple intercept model (ing ~ 1), which estimates the probability of the dependent variable at the population level without taking any conditions (or effects) into account. Such a model assumes that all authors exhibit identical behavior and use the innovative variant at the same rate. Second, we fit a varying intercept model, which estimates the population-level rate or probability of the dependent variable while taking differences between authors into account (thus “correcting” the population estimate for differences between individuals).

The output of Bayesian regression models should be understood as follows: they do not report a single, most likely coefficient combined with a p-value, but an estimate coefficient mean, an error rate, and a credible interval within which the estimate is predicted to fall. In Table 3, we report the mean estimate of the intercept (to be understood as the log odds of the innovative variant for the entire population) for both the simple intercept and varying intercept models. The simple intercept model estimates the intercept mean at 0.91, reporting a 95% credible interval (or CI) between 0.88 and 0.95. The varying intercept model, described in the second column, lists a population-level effect as well as a group-level effect (i.e., varying author intercept). The main difference with the simple intercept model is that the varying intercept model yields a 95% credible interval that covers a much broader range (between 0.67 and 1.24).Footnote 8 Because the varying intercept model allows for intercept corrections by individual author, the increased range of the credible interval indicates substantial interindividual variation in terms of how often ing-Ø is used.Footnote 9

Table 3. Model comparison of simple intercept model, predicting the posterior probability of the dependent variable at the population level, and varying author intercept model predicting the posterior probability of the dependent variable and correcting the population estimate for differences between individuals (group level effects). Number of observations = 16629, chains = 4, iterations = 4000, warmup = 1000, thin = 1

The next step is to assess whether the fitted varying intercept model is better at generalizing to any new, out-of-sample data than the fitted simple intercept model. To this end, we can perform a model evaluation by means of Leave-One-Out cross-validation, or by examining their Widely Applicable Information Criterion (WAIC; Gelman, Hwang, & Vehtari, Reference Gelman, Hwang and Vethari2014; Watanabe, Reference Watanabe2010).Footnote 10 Smaller WAIC values are considered superior, but it is not immediately clear how much smaller the WAIC values should be. As such, we also calculate the WAIC weights, which take a value between zero and one and should be understood as the posterior probability that a particular model makes better out-of-sample predictions.Footnote 11

In Figure 1, the WAIC value of the varying intercept model is estimated at 19,052, which is 875 units smaller than that of the simple intercept model, which is estimated at 19,928. Figure 1 also demonstrates that the difference between the WAIC scores remains substantial, even when the standard error range of the WAIC estimates (represented by the width of the lines running through the dots) is taken into account. This suggests that the varying intercept model, which corrects estimates for interindividual variation, exhibits a better fit for the data, confirming our basic hypothesis of there being nontrivial differences between authors.Footnote 12 It is this model comparison procedure that has been applied to all models presented in the analysis below.

Figure 1. WAIC estimates and standard error of simple intercept model and varying author intercept model.

Model overview

The assessment of the three hypotheses hinges on the comparison of twenty-two models in total. A full overview of each model can be found in Table 4.Footnote 13 The models can be divided into four groups: base models, age-only models, determiner-only models, and full models.

Table 4. WAIC and WAIC weight (rounded to 0.000001) for all models, ranked by WAIC score (ascending)

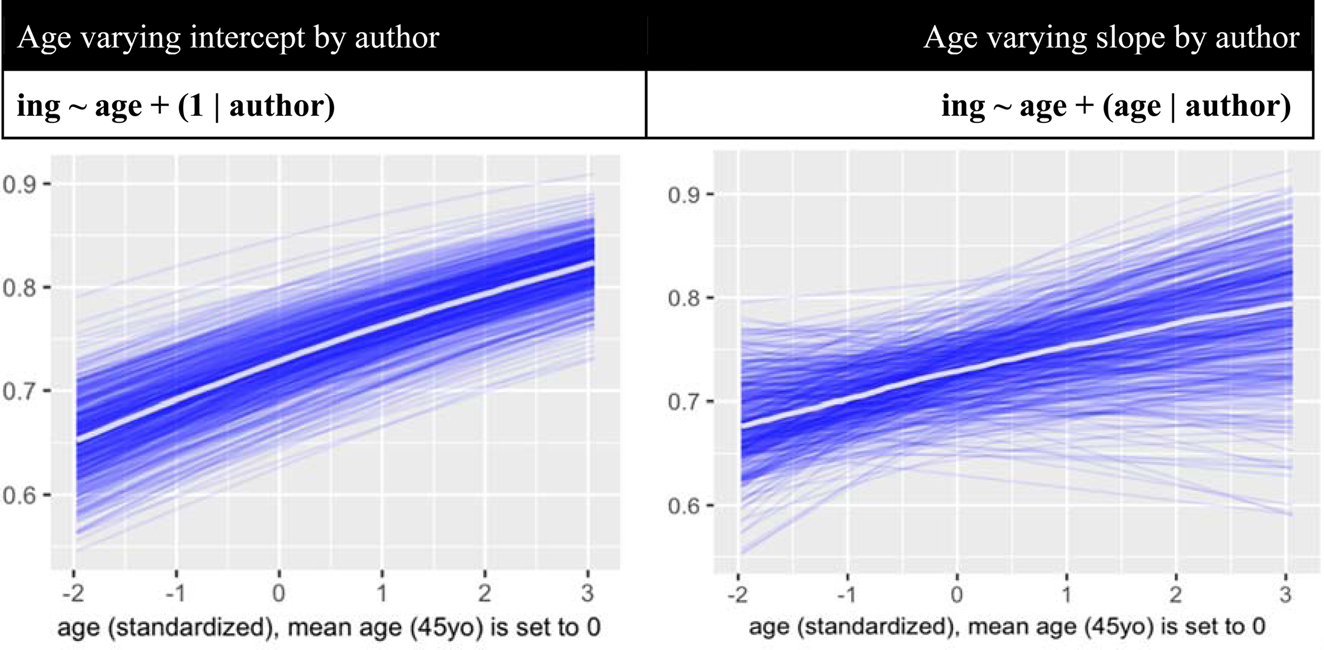

As the first hypothesis stated that individuals change the extent to which they use the conservative (ing-OF) and innovative variant (ing-Ø) during their lifespan, we need to establish that a model including an independent variable “age” (e.g., ing ~ age) provides a better fit for the data than the base model (ing ~ 1).Footnote 14 Additionally, we wish to determine whether there is interindividual variation in the data with respect to these changing usage rates. We can model interindividual variation in two different ways. The first way is to simply add age as a fixed effect to the varying intercept model (ing ~ age + [1|author]). In such a model, we can correct the population-level intercept for interindividual variation (meaning that the proportion of variant usage can differ among individuals), but we still assume that the direction in which any potential lifespan change proceeds is identical across all individuals. In other words: while the population-level intercept is corrected for interindividual variation, the slope is not. Alternatively, then, we could introduce interindividual variation as a ”varying slopes” model (ing ~ age + age|author), which does allow for individual differences in terms of the direction of the change. The difference in how ing-nominal usage across the lifespan of individuals is modeled by a varying intercept model (left, by means of parallel lines) and varying slopes model (right, by means of nonparallel lines) is visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Effect plots of varying intercept model and varying slope model (n = 500).

The second hypothesis relates to the effect of the grammatical context in which the ing-nominal is used. As such, we include three “determiner only” models in which the main effect ”determiner” is included, either in isolation or in relation to the behavior of individual authors with respect to these determiners (ing ~ det; ing ~ det + [1|author]; ing ~ det + [det|author]).

Finally, the third hypothesis relates to the combined effect of age and grammatical context. Besides the models where either age or determiner are considered as the only fixed effects, we also consider a number of “full” models, in which a range of different feature combinations are tested. The most basic version of the full model includes “age” and “determiner” as fixed effects, without including any random effects (ing ~ age_sd + det). A slightly more complex model also includes the interaction between “age” and “determiner” as a fixed effect (ing ~ age_sd * det). We also included versions of these models where the intercept is corrected for variation between authors (ing ~ age_sd + det + [1|author]; ing ~ age_sd * det + [1|author]). Finally, full model versions were fitted with varying author slopes for age (ing ~ age_sd + det + [age_sd|author]; ing ~ age_sd * det + [age_sd|author]), determiner (ing ~ age_sd + det + [det|author]; ing ~ age_sd * det + [det|author]), the interaction of age and determiner (ing ~ age_sd + det + [age_sd:det|author]; ing ~ age_sd * det + [age_sd:det|author]), and a combination of age, determiner, and their interaction (ing ~ age_sd + det + [age_sd*det|author]; ing ~ age_sd * det + [age_sd*det|author]).

Results

Model comparison

Table 4 lists the specifications for all models. The models are ranked according to their WAIC estimates (and accompanying weights). The estimated effective number of parameters per model is also listed (p_WAIC). To further discuss the effect of age and determiner type across authors, we report the results of the model with the highest WAIC weight (ing ~ age_sd + det + [age_sd*det|author]) in the next section (“Selected model”).

The two models with the lowest WAIC estimates are the most complex models, which include age, determiner, and their interaction as random effects (with varying author slopes). The model comparison supports the proposal that both age and grammatical context are meaningful parameters and that there is substantial variation between individuals with respect to those parameters. Particularly, the inclusion of grammatical context appears to have a substantial positive effect on the estimated prediction error of the model, as evident from the large difference between the WAIC values of the model that solely factors in determiner as a fixed effect (13067.1 [standard error: 158.5]) from the most complex age-only model (18856.5 [standard error: 118]).Footnote 15

Selected model

Table 5 summarizes the selected model's parameters. At the population level, the presence of a determiner has a strong negative effect: ing-Ø is less likely to occur following a possessive (mean coefficient estimate: −1.36 [95% credible interval: −1.69;−1.02]), a definite article (−3.78 [CI: −4.22;−3.29]), or any other determiner type (−3.35 [CI:−3.77;−2.86]). Age appears to have a small, positive effect (0.20 [CI: 0.01−0.40]). These effects are on the log-odds scale, which means the positive effect estimate of age can be interpreted as the odds of ing-Ø increasing by 20% as the age of the authors increases.

Table 5. For each parameter, we provide the population-level mean estimate coefficient (Estimate), the standard deviation of the posterior distribution of the estimate (Est.Error), and the 95% Credible intervals (CI lower bound and CI upper bound). Rhat helps evaluate the estimate the posterior distribution of the parameter (Rhat = 1.0 indicates convergence). The covariance matrix of group-level effects can be found in the online repository

Interindividual variation between authors can be examined by considering the estimated standard deviations at the group level. With the exception of the interaction between age and definite article and “other” contexts, the mean standard deviation estimates as well as their lower bound are clearly away from zero, which indicates the relevance of including the random intercept and random slope terms.

To better understand these figures, it is helpful to scrutinize the interaction between age and grammatical context per author, as visualized in Figure 3. For each graph in Figure 3, the y-axis represents the posterior probability of the incoming variant, ing-Ø. The x-axis represents a standardized representation of age, whereby the mean, which is set to zero, should be understood as approximately forty-five years old (the average age at which tokens were produced). From these figures, it is apparent why grammatical context has a substantial effect on the explanatory power of the model: despite interauthor variation with respect to the coefficient estimates per grammatical context, the probability of ing-Ø is highest when the ing-nominal is not preceded by a determiner (line marked with dots), followed by possessive contexts (line marked with squares), and lowest when the ing-nominal is preceded by a definite article (unmarked line) or other type of determiner (e.g., indefinite article, demonstrative, etc.; marked with triangles) for the majority of each author's life, mimicking the determiner constraint hierarchy observed at the population level.

Figure 3. Effect plots of interaction effect: age*det|author.

The figure also helps clarify why the effect of the inclusion of age as a predictor variable appears to be more modest: demonstrable age effects are not present for every individual in the sample. This is either because there is insufficient data to factor in age for some individuals (e.g., Aphra Behn, George Swinnock), or because usage rates appear to have remained largely stable across their lifespan (e.g., Thomas Pierce, William Penn). Furthermore, there appears to be quite some variation between individuals with respect to the interaction between age and grammatical contexts, particularly in the case of possessive determiners (standard deviation: 0.71 [CI: 0.33-1.26]).

Finally, the patterns in Figure 3 may also help identify individuals that seem to alter their grammatical preferences across their lifespan under certain grammatical conditions. An overview of the observed changes is presented in Table 6, which may help indicate how typical certain trajectory types may be (Sankoff, Reference Sankoff2019:223). Note that we treated the observed patterns very conservatively: despite there being more apparent patterns of change in the raw data, we retained the default assumption of stability if the 95% credible interval ranges presented in Figure 3 allow for horizontal (nonascending or nondescending) trend lines.Footnote 16 In total, eight individuals were flagged as altering their usage rates of ing-OF and ing-Ø. Of these eight individuals, there are five cases where the raw data suggest the possibility of a constraint change. For some individuals, such as Gilbert Burnet, the constraint change is a partial one: Burnet exhibited mixed usage but turned to categorical usage of ing-Ø in determinerless contexts later in life. While it is difficult to statistically verify categoriality, the rightmost (i.e., latest) mean posterior probability estimates of the relevant categories for these individuals closely approaches one.

Table 6. Observed changes and metadata per author (excluding Aphra Behn and George Swinnock)

A full constraint change may be attested for two individuals: the preferences of Peter Heylyn and William Prynne (the first and second author listed in Figure 3), born in 1599 and 1600 respectively, appear to switch radically from ing-OF to ing-Ø in possessive contexts. Given the low raw frequencies (twenty-nine tokens in total), and the possibility of more superficial, stylistic explanations, we should consider Heylyn's patterns with a healthy dose of uncertainty. Still, we could tentatively suggest the following: In his early prose and letters (before age thirty-seven), Heylyn exhibited variable use of the conservative (19%) and progressive variant (81%) in determinerless contexts. In contexts with a nominal determiner, however, Heylyn's early life grammar seemed to be largely or perhaps even entirely conservative: in the context of a possessive preceding the ing-form, the direct object of the ing-form required a periphrastic realization with of—conforming to the internal structure of a noun phrase. Later in life, Heylyn's writings start to allow progressive, mixed forms, and ultimately Heylyn develops a clear, near-categorical preference for the progressive form following possessives after the age of sixty. A similar picture emerges from the raw usage frequencies of William Prynne, who appeared to be categorically conservative in possessive contexts before the age of thirty-six but fully turned toward the progressive variant after the age of fifty-six.Footnote 17 Thus, both Heylyn and Prynne may have categorically switched to the progressive variant when a possessive is involved around similar ages (sixty and fifty-six respectively), and times (in 1659 and 1664).

Given these results, the question arises whether the observed trends can be understood as a full constraint change, where these individuals categorically switch from exclusively using a conservative variant to exclusively using the progressive variant under a given grammatical condition.Footnote 18 An interesting question with respect to such possible (partial or full) constraint changes is whether an author's apparent adoption of a new system (under a particular constraint) also involves a rejection of the old system, which would be even stronger evidence for a qualitative change. However, unless we find metalinguistic comments in their works (which we have not so far), this will remain an open question.Footnote 19 With respect to direction, it appears that all (possible) constraint changes are in accordance with the larger population-level development (loss of ing-OF in bare and possessive contexts).

Discussion: inter- and intraindividual variation and change

What emerges from the results is that, while neither full nor partial inventory changes (where an individual ceases to use ing-OF and/or adopts ing-Ø) occur, we do observe a fair number of frequency and (to a lesser extent) constraint-based age effects. Additionally, the vast majority of observable quantitative shifts across all grammatical contexts appear to be in the direction of the larger population-level development, showing an increase of ing-Ø.

There are, however, two “retrograde” changers (Wagner & Sankoff, Reference Wagner and Sankoff2011). The first is John Bunyan, who appears to become incrementally more conservative than his peers (Age coefficient estimate: −0.54 [95% CI: −0.78 −0.32]). The second is George Fox, who similarly turns to making more conservative choices (Age coefficient estimate: −0.35 [95% CI: −0.58 −0.13]). These results corroborate earlier findings on interindividual variation in linguistic lifespan change trajectories: the frequency with which individuals use variants need not but can change, and when it does, it commonly is, but need not be, in line with the population-level development (e.g., progressive as well as retrograde change attested in panel studies by Wagner & Sankoff [Reference Wagner and Sankoff2011] for inflected futures in Montreal French; Buchstaller [Reference Buchstaller2015] for quotative be like in Tyneside English; Standing [Reference Standing2021:360-72] for cleft constructions in Early Modern English; also see Anthonissen [Reference Anthonissen2020:247]). What is discussed somewhat less commonly than interindividual variation in lifespan trajectories is that there may also be intraindividual variation in this respect: for many authors where frequency-based change is attested, this change may be restricted to only a few grammatical contexts. Furthermore, an interesting example in our data set is George Fox, who becomes more conservative if the ing-nominal is not preceded by a determiner, while his choices following possessives likely concur with the population-level pattern.Footnote 20

In other words, while it may be uncommon, individuals need not consistently develop toward or away from the community trend in every respect (also see Buchstaller et al., Reference Buchstaller, Krause-Lerche, Mechler, Beaman and Buchstaller2021). Such intraindividual variation thus may not only be attestable across the sets of variants an individual employs (Bergs, Reference Bergs2005:255-56), but also across the grammatical contexts that condition a single variable set.

Confronted with these figures, the question arises whether labile linguistic behavior can somehow be linked to the contextual metainformation included in the corpus. With respect to stable speakers and speakers who adapted (slightly) in the direction of the community trend, there appear to be no striking differences in terms of social or geographical (in)stability. By way of illustration, Tillotson and Dryden were born one year apart, belonged both to the upper class, and both went to Cambridge University in the early 1650s. After their studies, they both moved to London around the same time (1656 and 1657 respectively). Virtually all of their published work was written while they lived there. Yet, while Dryden shows a frequency (and possibly even a constraint) shift along the lines of the community trend, Tillotson is stable throughout his life. More generally, this could either mean that the differences can be explained by some unidentified factor or that some speakers are simply more likely to model their usage rates to the perceived community trend later in life (due to different ”cognitive learning styles,” see for example Riding & Rayner, Reference Riding and Rayner1998).

Regarding the two individuals who become more conservative, George Fox and John Bunyan, there are some striking similarities between them that may go some way in explaining their retrograde behavior (see Sankoff [Reference Sankoff2018] and [Reference Sankoff2019] for an overview of studies attesting retrograde change). First, after a relatively uneventful youth spent in small countryside communities, both experienced a more diversified social life.Footnote 21 Fox spent about a year in London at the age of nineteen, whereas Bunyan enlisted in the Parliamentary army between the age of sixteen and nineteen. This may have led them to accommodate to language use in more urban settings and establish the grammar shown in their first published work. However, some years later they were both cut off from society, being repeatedly imprisoned for their dissenting religious views and actions. Fox was in prison at least ten times (between 1649 and 1675), adding up to a total of more than six and a half years, or about 15% of his writing career. Bunyan was in prison uninterrupted (though he was allowed outside occasionally) for twelve years from 1660 until 1672, and another half year in 1676 (almost 40% of his writing career). While early modern prisons were rather “porous” and brimming with short-term inmates and visitors, normal social life was nevertheless sincerely disrupted, and prisoners were confined to their own cells in poor conditions for much of their time (Murray [Reference Murray2009:147, 152]). When in such relative isolation, one may fall back, due to the lack of sustained input from a more constructive social network structure, on entrenched language patterns such as they knew from youth (see the conservative behavior of the English poet Browning living in Italy [Arnaud, Reference Arnaud1998:132-33]). Fox and Bunyan's inmates, most of them from a lower class origin, may have been an additional conservative influence (see also the linguistic stagnation in prison documented in Baugh [Reference Baugh, Guy, Crawford, Schiffrin and Baugh1996:408-9], where this is interpreted as a case of covert prestige). The lower classes were typically less mobile and therefore less influenced by London life, which played a central role in many linguistic changes at the time, including the shift from ing-OF to ing-Ø (Nevalainen, Reference Nevalainen2015:288).Footnote 22

Besides Fox and Bunyan, there is one other speaker, William Prynne, who was incarcerated for about ten years or one fifth of his writing career. He was transported to the island of Jersey, where he was kept “incommunicado,” not even allowed a pen and paper (Cressy, Reference Cressy2018:741). His isolation was therefore more severe than in either Fox's or Bunyan's case. This period of seclusion may have slowed down his accommodation to ongoing change, similar to Fox and Bunyan. However, while he was imprisoned first around the same age (thirty-three) as Bunyan's (thirty-two), the majority of his time in prison (seven out of ten years) occurred in the first half of his career (between 1633-1640). After 1640, Prynne remained productive and mostly free until 1668 and was generally well-connected, even becoming MP in 1648. While reconnecting to the speech community again, Prynne caught up on the ongoing changes, which might partly explain his more radical shift in preferences (in line with the community trend) in possessive contexts (also see Petré et al. [Reference Petré, Anthonissen, Budts, Manjavacas, Silva, Standing and Strik2019:110] on a similar shift in the language of Margaret Cavendish after her return from exile). Prynne's political success and general well-connectedness after his seclusion distinguishes him from Fox and Bunyan.

Finally, together with Nathaniel Crouch, Fox and Bunyan are the only authors in our sample who did not grow up in an upper-class family, instead being the sons of middle class artisans. They are also the only ones that did not attend university. Yet, what sets Fox and Bunyan apart from Crouch is that they were by far the least connected to “society” in its sense of the aggregate of fashionable, wealthy, or otherwise prominent people. Nathaniel Crouch, as a successful London-based publisher, was in the middle of buzzing London city life. By contrast, Fox spent most of his time preaching throughout the country, experiencing relatively few periods of stable participation in large-scale weak-tied urban communities such as London. Bunyan, in turn, was a poor man for most of his life and, as a result, bound to the countryside of Bedfordshire. It is interesting to note that Bunyan, who is arguably the author with the smallest social network, becomes more conservative across the board, whereas Fox may pick up at least on the innovation in possessive contexts. Yet overall, the similarity of their life paths (extended period of isolation, class background, lack of university attendance) seem to provide a plausible group of explanations for their shared retrograde behavior.

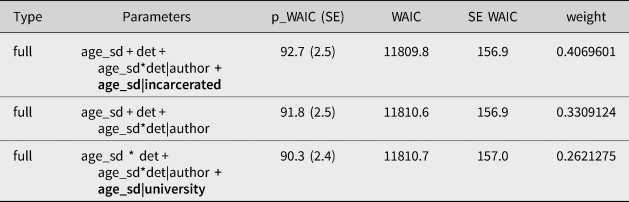

To tentatively explore whether these effects could help explain interauthor variation with respect to age effects, the selected model (ing ~ age_sd + det + age_sd*det|author) could be further extended with the parameters “incarcerated” (levels: yes/no, indicating whether a given author has spent more than five years imprisoned) and “university” (levels: yes/no, indicating whether the author has attended university).Footnote 23 These factors should be understood as groupings that introduce slope variance with respect to the factor age. As such, they are modeled as group-level effects with varying age slopes. The resulting models were submitted to a WAIC model comparison, presented in Table 7.Footnote 24

Table 7. WAIC estimates and WAIC weight (rounded to 0.0000001) for additional models, ranked by WAIC score (ascending)

While the highest weight is assigned to the model including incarceration, it does not bring about a substantial reduction in the WAIC estimate. Considering the fact that the scores are near identical for each model, it remains undetermined whether the extended incarceration model indeed yields a better fit. We do, however, invite readers to extend our analysis to a new sample of authors that is more nicely balanced with respect to isolation versus connectedness, middle versus upper class, and/or (lack of) university education, or to explore alternative social dimensions by adapting our analysis scripts for use on the openly released data.

Conclusion

In recent years, a growing number of studies have indicated that an individual's grammar is not necessarily a fixed system and may be subject to change even after what is traditionally understood as the critical acquisition period. This has been amply shown for gradual shifts in pronunciation and morphophonology (e.g., Bowie & Yaeger-Dror, Reference Bowie, Yaeger-Dror, Honeybone and Salmons2015; Harrington, Palethorpe, & Watson, Reference Harrington, Palethorpe and Watson2000; MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2017; Nahkola & Saanilahti, Reference Nahkola and Saanilahti2004; Sankoff & Blondeau, Reference Sankoff and Blondeau2007). Recent studies have moreover shown that it also applies to morphosyntactic constructions, which may be adopted (Anthonissen & Petré, Reference Anthonissen and Petré2019; Petré & Anthonissen, Reference Petré and Anthonissen2020; Petré & Van de Velde, Reference Petré and Van de Velde2018), significantly expanded (Anthonissen, Reference Anthonissen2020; Neels, Reference Neels2020), or changed (Buchstaller, Reference Buchstaller2015, Reference Buchstaller2016; Standing & Petré, Reference Standing, Petré, Beaman and Buchstaller2021) beyond the critical period. Similarly, lifespan change has also been attested in contexts where a choice between morphosyntatic variants needs to be made (e.g., Raumolin-Brunberg, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg2005, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Nevala and Palander-Collin2009; Raumolin-Brunberg & Nurmi, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Narrog and Heine2011). While several of these changes may be regarded as stochastic shifts in preference, some changes do appear to result in a rejection of one of the variants, which could ultimately point to qualitative change, and stochastic shift also cannot explain cases where a language user starts to adopt grammatical innovations later in life. What may set such changes apart from grammatical change rooted in child language acquisition is that changes later in life may involve more (top-down) explicit learning (similar to second-language learning, see Anthonissen & Petré, Reference Anthonissen and Petré2019:3; Dąbrowska, Reference Dąbrowska, Dąbrowska and Divjak2015:661), but the resulting shifts in representation may arguably be just as “qualitative.”

Our study corroborates earlier findings that individuals can change the rate by which they use the competing morphosyntactic structures across their lifespan (see, among others, Buchstaller, Reference Buchstaller2015; Raumolin-Brunberg, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg2005, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Nevala and Palander-Collin2009; Raumolin-Brunberg & Nurmi, Reference Raumolin-Brunberg, Nurmi, Narrog and Heine2011; Wagner & Sankoff, Reference Wagner and Sankoff2011), and, for the majority of individuals, this change proceeds in the direction of the ongoing change in the rest of the community. Yet, in line with Baxter and Croft's (Reference Baxter and Croft2016) suggestion that individual speakers may differ in their inclination to adjust their behavior to the community (also see Anthonissen, Reference Anthonissen2020), we also found nontrivial interindividual variation regarding the extent to which these usage rates change, as well as the direction in which they change (with retrograde changers such as John Bunyan opposing the general, community-directed patterns of change, which may partly be the result of their particular life trajectories).

We additionally established that there is intraindividual variation in the slopes and direction of change under different grammatical conditions. As such, we further extend Bergs’ (Reference Bergs2005:255) study on intraindividual variation, which demonstrates that individuals need not be consistently progressive or conservative in all aspects of their grammar. While Bergs considered the choices of individuals with respect to multiple morphosyntactic variables without factoring in grammatical constraints, we suggest that, even with respect to a single variable (ing-OF versus ing-Ø), individuals can also become more progressive over time with respect to some grammatical contexts while remaining stable or even becoming more conservative in others. That the rate of change attested need not be constant across grammatical contexts in the linguistic output of individuals (as it is assumed to be at the community level, see Kroch's [Reference Kroch1989] Constant Rate Hypothesis) does, however, call for further empirical inquiry.

Finally, we also probed into the question of whether individuals may also “participate” in qualitative change by reaching a more advanced stage of the community grammar during their lifespan. In a recent study with panel data, Buchstaller et al. (Reference Buchstaller, Krause-Lerche, Mechler, Beaman and Buchstaller2021:32-3) suggested that “evidence of inventory change is rare and difficult to come by,” and “speakers are less likely to change the constraints that govern the use of a variable than they are to change proportional use of a variant” (also see MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2019). Finding evidence of full (and even partial) inventory changes in real-time corpus data may be equally difficult or even impossible, particularly with protracted changes such as the one examined in the present study (Nevalainen et al., Reference Nevalainen, Ramoulin-Brunberg and Manilla2011). Yet, when taking a constraint-based definition of qualitative change (which is facilitated by large-scale individual-oriented corpora such as EMMA) and identifying an appropriate time window (e.g., when the population-level patterns these individuals model themselves toward are sufficiently unstable to allow for more radical adjustments), we may in fact attest cases where individuals allow novel variants to diffuse to (and/or take over in) new grammatical contexts, albeit indeed to a lesser extent than frequency-based changes.