INTRODUCTION

In the winter months of 1623, the young Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) arrived in the bustling port city of Genoa, eager to advance his burgeoning reputation as Europe's next great portrait painter.Footnote 1 Two years after his initial arrival in Italy, and energized from his travels across the peninsula, Van Dyck would paint a masterpiece of his Italian period—namely, the portrait of Genoese noblewoman Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo (d. 1643) accompanied by a Black African servant (fig. 1).Footnote 2

Figure 1. Anthony van Dyck. Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, 1623. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Despite being one of Van Dyck's most celebrated works, the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo has avoided significant scrutiny that goes beyond stylistic and iconographic interpretations. This is likely owing to the dearth of primary sources pertaining to the painting's conception, and the lives of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo and any dark-skinned servant she may have employed.Footnote 3 Seeking to bypass these documentary gaps, this article pursues alternate methodological viewpoints. Anthropologist Felipe Gaitán Ammann has rightly noted that “the materiality of objects is not simply instrumental, but constitutive of the cultural and political significance, meaningfulness, and symbolic power of things.”Footnote 4 Examining the portrait through the prism of material culture studies is a particularly effective strategy; it allows the Portrait to be considered as an artifact that shaped and responded to the shifting sociocultural dimensions of early modern Genoa and the world beyond. Further, when approached from a globalized perspective, new light is shed on the ways in which practices of material consumption impacted the painting's composition. As Beverly Lemire has shown, “early modern globalism elicited and shaped new consumer practices in diverse world regions.”Footnote 5 These new consumer practices, which fueled and were fueled by increasingly intense and formalized global commercial systems, constructed a “material cosmopolitanism” defined as “a wider habitual involvement in diverse material media resulting from global commerce and the new situational activities arising from global trade.”Footnote 6 This article argues that the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, which was painted for the fashionable and cosmopolitan Genoese patriciate, is a laudation of globalized material consumption and human encounter. Such a story of material cosmopolitanism necessitates an equally cosmopolitan framework, operating across disciplinary and geographical boundaries.Footnote 7 Adopting this viewpoint unlocks new levels of meaning that have previously been overlooked by scholars, and provides new understandings of the experiences, aspirations, and motivations of the society for which the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo was made, and within which it was viewed.

Indeed, this portrait could only have been painted in a dynamic center of global encounter and public display like Genoa. When Van Dyck arrived in the capital city of the powerful maritime Republic, he found an affluent and cosmopolitan metropolis, built on the fortunes of noble merchant-bankers.Footnote 8 Genoese society was preoccupied with self-definition through material consumption and visual spectacle. Indeed, the city's crammed geography facilitated rituals of display. The seventeenth-century English traveler John Evelyn (1620–1706) remarked that “the city is built in the hollow or bosom of a mountain whose ascent is very steep, high, and rocky . . . it represents the shape of a theatre; the streets and buildings so ranged one above another, as our seats are in play-houses.”Footnote 9

Within this city-theater, Genoa's citizens were greatly attuned to the importance of costuming. Garments and accessories were “symbolic postures [that] . . . could be quickly read by observant viewers.”Footnote 10 Moreover, as Lemire and Giorgio Riello have demonstrated, the global connections forged and strengthened during the early modern period “enabled material inspiration in the making of dress.”Footnote 11 The Genoese were cognizant of the origins of the materials they wore and held a sophisticated understanding of the cultural, political, and economic currency of clothes. And as the city's nickname La Superba might suggest, they were proudly attired: English traveler Richard Lassels (1603–68) was struck by the sartorial splendor he witnessed among the Genoese, noting in his travel diary of 1670 that “if ever I saw a Town with its Holy-day clothes always on, it was Genua.”Footnote 12 Accordingly, this fascination with sartorial spectacle translated to the artwork commissioned by Genoa's nobility. From the middle of the sixteenth century the Genoese elite held a fierce predilection for large-scale portraiture, and this need was expertly fulfilled by Van Dyck during his stays in the city.Footnote 13

This article begins with a contextual overview. The first section explores the unique mercantile culture that took root in Genoa, which gave rise to a powerful merchant diaspora. The second and third sections undertake a close reading of the garment forms and materials worn by and associated with Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo. To date, a household inventory of Elena's family has not been found. As such, it is difficult to confirm whether the clothing and accessories depicted in her portrait existed in Elena's wardrobe at the time of painting. However, through analysis of contemporaneous visual and documentary evidence, I demonstrate that her painted dress reflects Genoese elite sartorial cultures of the time. Elena's garb expresses the privileged access to the Americas enjoyed by her family as well as messages of power and prestige, communicated through the novelty and luxury of the materials that shaped her clothing.

The same mercantile culture that influenced Elena's dress also determined the presence and attire of the Black servant. Even more so than Elena, little is known about the life such an individual may have led. Nonetheless, the figure warrants critical investigation. The final sections of this article argue that he is more than a trope of Baroque portraiture. Through a detailed examination of the cultural and economic forces that shaped encounters between the Genoese and diverse peoples from Africa, it becomes evident that the attendant's garb serves to condense time and space, referencing Genoese activities in both the Old World and the New through his body and dress. As such, this article investigates the impact of global commercial networks on the construction of specific identifications through clothing and adornment, as seen in the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo. Through a reconsideration of this portrait through a global lens and the study of material history, this article seeks to recover the forces that shaped the lives of the sitter, her attendant, the artist, and the portrait itself.

THE GLOBAL GENOESE

The Republic of Genoa represents an idiosyncratic polity within early modern Italy, defined by the private wealth, mercantilism, and cosmopolitanism of its elite citizens in the capital city and abroad. The ambitious commercial activities undertaken by private individuals, and “the early idea of the city as a marketplace . . . [was] placed at the heart of the Genoese life—and, therefore, of its outward projection.”Footnote 14 Built at the edge of the western Mediterranean, the city produced generations of seafaring merchant-entrepreneurs. Their omnipresence in trade networks helped coin the phrase Genuensis ergo mercator: Genoese therefore a merchant.

Genoa gained prominence during the medieval period thanks to its extensive commercial and colonial enterprises in the Levant and Black Sea region. The Genoese organized a dense network of intermarried and professionally linked families that facilitated the movement of goods across these regions. They also traded with North and West Africa; with actors present in Tunisia; with the Mamluk, Mali, and Songhai Empires; and with the Canary Islands.Footnote 15 The fortunes of the Genoese changed when, in 1528, Admiral Andrea Doria (1466–1560) shifted Genoa's alliance from France to Spain. The Republic was reestablished under imperial protection by means of a new constitution, and the Genoese cemented their position within the rapidly expanding Spanish Empire. Genoa's mutually beneficial relationship with the Spanish Habsburgs was built upon military, fiscal, and trade agreements.Footnote 16 This was buttressed by aligning sociocultural values and a staunchly Catholic entente between the two states against the ever-present threat of Islam in the Mediterranean.Footnote 17

The second pillar of the Republic's wealth was international finance. From 1528, Genoese financiers both in Liguria and in Spain became increasingly indispensable to the Crown, not only providing maintenance for the royal household but also funding expeditions to the Americas.Footnote 18 A statement from the Venetian ambassador to Spain in 1573 is telling: “The best merchants in the court are the Genoese. But they dedicate themselves little to real commerce that consists of sending merchandise from one country to another. On the contrary, the Genoese of the Spanish court, among whom we can find at least one hundred principal great houses, devote themselves primarily to monetary transactions.”Footnote 19 Genoa and Spain had become mutually dependent partners. The Republic financed Spain's imperial ambitions, and in turn the Spanish Crown reimbursed its Genoese financiers with tens of millions of ducats of American silver and gold each year.Footnote 20 This relationship ushered in an age of unparalleled wealth, influence, and material consumption for the Genoese.

Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo's closest relations typified the worldly Genoese merchant-elite. Her father, Giovanni Giacomo Grimaldi (dates unknown) was a senator of the Republic in 1606 and her brother Geronimo (1597–1685) would be made cardinal in 1643. Her husband Giacomo Cattaneo (b. 1593) was a member of the Della Volta branch of the Cattaneo clan and held the title of marquess. Furthermore, her husband's grandfather, Isnardo Cattaneo (fl. 1580) had overseen the family's trade interests in Spanish-governed Antwerp during the sixteenth century with Giacomo's father Filippo (fl. 1604), who was consul of the Genoese nation.Footnote 21 This division of the Cattaneo enterprise traded in textiles. Their activities likely led them to encounter a young Van Dyck through dealings with his silk-trading father Frans van Dyck. Similarly, Van Dyck may have encountered the Cattanei in the workshop of his mentor Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), as the family commissioned a tapestry cycle from the Flemish master in 1616.Footnote 22

Genoa's relationship with Spain provided crucial access to the new world of Atlantic trade. Merchant colonies had been established during the medieval period in Seville and Cadiz, and Genoese traders were well situated to take full advantage of transatlantic commerce. The fortunes of both the Grimaldi and Cattaneo (including the Della Volta) were intricately interwoven with the Spanish Atlantic market. As early as 1504, the governor of Hispaniola complained to King Ferdinand (r. 1474–1504) that most of the goods entering the island belonged to the Genoese and to foreigners.Footnote 23 In Seville, the “emporium of the Indies,”Footnote 24 the Cattanei (Hispanicized to Cataño) was the third largest family firm, with thirteen representatives, and the Grimaldi were fourth largest, with nine representatives.Footnote 25 Both firms were involved with commerce, finance, and the court. In the sixteenth century, Jácome and Juan Francesco de Grimaldo were some of the wealthiest and most active members of the Genoese colony and were largely preoccupied with providing loans to merchants headed to the Americas.Footnote 26 Batista Cataño also issued loans and sales credits, while Alejandro and Jácome Cataño attended court as financiers.Footnote 27 Indeed, Cattaneo merchants had been involved in American trade from the outset. Rafael Cataño worked as an agent for Christopher Columbus on Hispaniola and “the family were privy to the very latest information regarding discoveries in the New World and emerging trading opportunities.”Footnote 28 By the 1530s, Cattaneo agents occupied important administrative and commercial positions within Spain's American empire.Footnote 29 The Grimaldi were also present in the Americas from early on. In 1506 Jeronimo de Grimaldi traveled to Santo Domingo to oversee the affairs of his uncle Bernardo. Four years later, King Ferdinand granted Bernardo and his family the exclusive right to reside permanently in the Indies.Footnote 30 The intricacy of Genoese family trees, as well as the distances over which families spread, frequent intermarriage, and repetition of first names renders it challenging to define specific relationships between individuals. Nonetheless, the Genoese diaspora was known for its legal and commercial loyalty to its countrymen.Footnote 31 It can therefore be confidently assumed that, while branches of the Cattaneo and Grimaldi clans were situated in Spain and further afield, frequent travel and written contact, along with fiscal, familial, and trade links, strengthened the bonds between the Genoese at home and abroad. Thus, from the Ligurian city spun out numerous threads that connected Genoa in a web of international mercantile and financial interests.

The Americas represented a cornucopia of material wonders for Europeans. Precious metals could be found in rivers of gold, pearls were collected off the coast of Venezuela, and the most luminous emeralds available on the market were unearthed in Colombian mines. Moreover, American dyestuffs—including cochineal, logwood, and indigo—rivaled, if not outstripped, their Old World counterparts. Skins, pelts, shells, and feathers also reached European shores, and were welcomed with wonder and delight. Of course, American trade was not solely restricted to material goods. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Spain's Asiento de Negros system granted Genoese merchants, including the Grimaldi and Cattaneo, the license to trade enslaved people from Africa in Spain's American colonies.Footnote 32 Alongside the Portuguese, Genoa's traders were the first to settle on the Cape Verde Islands in the 1460s, which became the primary port of departure for slave ships.Footnote 33 It was thus on Genoese ships that captives were transported from the archipelago to Vera Cruz.Footnote 34

The Genoese were not solely westward in focus, however, and they retained their engagements in the eastern Mediterranean. From the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, the Cattaneo Della Volta were involved in alum production on the island of Phokaea;Footnote 35 Domenico Cattaneo, a distant relative of Elena's husband Giacomo, traded cloth in Theologos and Chios, and Lanzarotto Cattaneo traveled to Turchia to purchase grain for the Republic in 1475.Footnote 36 After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, trade slowed but was not completely stifled, as Sultan Mehmed II (r. 1444–46; 1451–81) was keen to uphold trade agreements with the Genoese.Footnote 37 As in Spain, the Genoese—including further relatives of Giacomo Cattaneo—operated in close proximity to power in Constantinople, functioning as vital players in the commercial networks that “developed in the orbit of the court.”Footnote 38 A significant facet of Genoese mercantile activities in the eastern Mediterranean was the slave trade. The largest slave markets were in Pera, on Crete, Chios, Cyprus, Rhodes, and Naxos, which were also home to Genoese settlements and colonies.Footnote 39 Similarly, Constantinople was a site for trading enslaved people, and the Genoese community was particularly active there.Footnote 40 By the seventeenth century, however, the influence of the Genoese in the Mediterranean waned as the pull of the Atlantic dominated Genoese interests.

With centuries of involvement in transnational trade by the time of Van Dyck's arrival, Genoa was a nation of cosmopolitans.Footnote 41 The Republic's merchants traded extensively in distant lands, adopting foreign customs and adapting to foreign environments. Accordingly, the Genoese were a font of global knowledge and experiences, and their identities were shaped by their interactions with the wider world. The keen ability of the Genoese to employ distinct cultural codes afforded them “immense creative potential. They . . . inspired new and hybrid objects, artworks, languages, and socio-economic or cultural practices which were themselves cosmopolitan.”Footnote 42 It thus follows that the Cattaneo Della Volta and Grimaldi, representing two of Genoa's most influential and widespread mercantile and banking families, would wish to immortalize their worldly identities through material and sartorial expression. As is made evident in the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, the global reach of the Cattanei and Grimaldi was of prime importance; the resulting composition undeniably places Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo in this world of global goods.Footnote 43

GLOBAL FORMS AND MATERIALS

On a world stage, Genoese actors dressed in specific forms and materials, exploiting the “inherent dialectic in clothing between . . . presentation and perception.”Footnote 44 Dress was a powerful vehicle with which to express a multitude of messages about the wearer and their many, varied, and overlapping identifications. Scholars including Ulinka Rublack, Ann Rosalind Jones, and Peter Stallybrass have persuasively argued that the wide availability, diversity, and intricacy of clothing secured its place as an essential facet of early modern culture.Footnote 45 For Jones and Stallybrass, “investiture, the putting on of clothes . . . quite literally constituted a person. [Investiture was] the means by which a person was given a form, a shape, a social function, a depth.”Footnote 46

With their Spanish connection, the Genoese, both at home and abroad, adopted and interpreted the fashions disseminated by Spain's court in a display of allegiance, aligning social, religious, cultural, and commercial interests. However, Spanish fashions in and of themselves were globalized and cosmopolitan. Dress historical scholarship often situates dress within specific locales, asserting that certain garment forms and materials are of a particular region.Footnote 47 Yet this approach can neglect sartorial cross-fertilization. Clothing was not created in a vacuum within a country's borders but instead referenced multiple cultures—not only through foreign materials and forms but also through their social significance.Footnote 48 Spanish styles spread across Habsburg territories and aligned states in Europe as well as the Americas, due in great part to the circulation of printed and painted images of the dynasty's rulers.Footnote 49 Yet in each locale, these fashions were translated and adapted by the local population. Moreover, cross-pollination occurred across trade centers aligned with Spain, like Antwerp, Prague, Milan, Naples, and Genoa, where Spanish dressing was brought into concert with foreign goods and local tastes.Footnote 50 Spanish fashion then, was not solely a top-down, geographically stable phenomenon, but was subject to influence from external forces and tastes.

In a Genoese context, the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo pictures Spanish-influenced cosmopolitan fashion through a dramatic depiction of dressing alla Spagnuola. Spanish styles were characterized by severity of form. The body of the wearer was completely enclosed within a structured mass of rich textiles. On top of a linen chemise, Elena would have worn stiffened stays and a busk which gives her torso its flat and tapering shape in the portrait. She wears a magnificent ensemble comprising a jacket with short hanging sleeves, a matching skirt, scarlet cuffs, and a grey lettuce ruff made of net.Footnote 51 Volume is concentrated at the lower half of Elena's body by either a conical Spanish farthingale, or verdugale and/or a padded roll tied at the waist. In either case, the painting does not clearly indicate which structuring undergarment is worn. Instead, it favors the affective drama of expansive flowing skirts over a faithful rendering of the garments. Her black jacket is embellished with rings of silk brocade gallon trim decorated with arabesques, which encircle her torso and inner sleeves. A thick band of gallon trim also runs the length and hem of her skirts. Although it is difficult to discern the fabric of her skirt, the stripe of highlight between her proper left fingers suggests it is a silk taffeta.

At first glance, this intricate attire reads as Spanish in construction. A closer reading reveals the cross-cultural nature of Spanish dress. Elena's jacket, called an ungaresca, adapts a style worn in Eastern Europe, characterized by an opening at the elbow. Indeed, as the garment's name suggests, this style was traditionally worn by Hussars in the Hungarian army.Footnote 52 Furthermore, the arabesque patterning on the jacket borrows from an Eastern design vocabulary, evidencing the Ottoman influence on Italy's silk production.Footnote 53 Finally, her ruff, made of a fine open net, appears to be of a style particular to Genoa.Footnote 54 As such, within one ensemble, the dressed figure of Elena encapsulates cosmopolitan dressing, translated through a Spanish lens.

Along with the specific forms of Elena's garments, the omnipresence of silk textiles in the portrait highlights another point of connection between Genoa, Spain, and the wider world. This luminous and costly fabric represented the apex of textile luxury across the globe for centuries; its glossy filaments united the world in a web of globalized trade.Footnote 55 Since its earliest production in Neolithic China, silk had been prized by elite classes for the variety of textures and luminosity of the textile. The portrait expresses the extent to which silk textiles were the foundational element in creating an elite ensemble. As German architect Heinrich Schickhardt (1558–1635) recorded in his travel diary of 1599, Genoa's citizens wore the finest silks and velvets in all of Italy.Footnote 56 With an extensive merchant diaspora in all the major silk centers across the Mediterranean basin, Northern Europe, and the East, the Genoese elite were a highly textile-literate society, whose coffers granted them access to the best cloth money could buy.

The Genoese Republic's silk production and consumption is well documented.Footnote 57 Silk was vital to Genoa's economic and political position in the Mediterranean, and the Republic's Spanish connection facilitated the stabilization of numerous silk-related industries.Footnote 58 Moreover, the Genoese bargained for commercial privileges that further cemented their centrality in a global silk industry. As a producer of finished products, Genoa imported raw materials from Naples and Sicily, two other polities under Spanish rule that were also home to textile-trading branches of the Cattanei and Grimaldi.Footnote 59 Silk products from other Italian regions were also traded and consumed by the Genoese. Florentine rascia, or rash, a luxury silk cloth, was regularly sent to the merchant Paul Vincenzo Sauli Rapallo in Cordoba by his uncle Teramo Brignole and his associates, who lived in Florence.Footnote 60 Silks also came from Spain; in 1609, Tobias Cataño bought 600 ducats worth of silks from Diego Castellano in Granada, including taffetas and satins of various colors.Footnote 61

As Genoa comprised one of Europe's classical silk production centers, however, local textiles were frequently worn in a display of the excellence of Genoa's silk industry.Footnote 62 Controlled by powerful merchant-entrepreneurs (setaioli) and guilds, silk trade was a key element in international commerce.Footnote 63 Since the Middle Ages, Genoese weavers had concentrated on the production of high-quality cloths. As such, silk techniques and technologies were heavily guarded and kept to the highest standards through regular guild inspection.Footnote 64 This must have been no small feat, as by 1600 over 60 percent of the city's population was involved in silk work.Footnote 65

Worn by a member of a textile-trading family, the cloth that makes up Elena's outfit inserts the sitter into a wider discourse on the reputation and the social and economic agency of silk, a material that, in the words of sixteenth-century writer Leonardo Fioravanti (1517–88), was “to the glory of God, and to the benefit of the world.”Footnote 66 Although surface detail on the painted canvas has been lost, what is visible indicates that the materiality of silk textiles was originally exploited to its fullest extent by Van Dyck (fig. 2). The cloth has been built up through transparent glazes of oil paint over a carbon black ground. Indeed, the materiality of the painting itself is significant, as the ground has been applied in such a manner that the texture of the canvas remains visible. Over this, layers of glossy glazes imitate the luminous quality of silk, and together with the canvas weave, the painted surface convincingly mimics the texture of a woven silk textile. Painted silks thus represent an ideal vehicle for the transmission of messages about Elena's status and wealth, as well as the international mercantile networks forged by the Cattanei and Grimaldi that facilitated that wealth.

Figure 2. Anthony van Dyck. Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, detail of hand holding silk skirts, 1623. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

MATERIALIZING BLACK

Elena's swathes of silk are perfectly suited to an exhibition of brilliantly colored cloth. In this, globalized trade comes to the fore, as fabric dyeing represents one area of Europe's sartorial landscape that was reshaped by American goods. New dyes met a thriving textile industry and supplemented local dye economies, which, within Europe's rising consumer culture, only increased demand for luxurious, processed cloth.Footnote 67

Color itself was a socially constructed and symbolically important matter. Prior to the invention of synthetic dyes in the nineteenth century, saturated dyes symbolized power and wealth. These colors were culturally linked to certain moral qualities, and with rank and position or caste.Footnote 68 Moreover, the best and longest-lasting colors were only achieved through labor-intensive and complicated dyeing processes, which increased the price of the finished fabric. However, a wave of new color entered the European wardrobe with American dyestuffs, which began to appear on the Continent from the late 1520s.Footnote 69 Appearing in tandem with novel dyes were new dyeing technologies and trends, which further influenced the chromatic possibilities of textiles. Cloth dyed with American stuffs came to signify the best in dyeing, and the wealth of the Indies.Footnote 70 In sum, these materials married the traditional powerful symbolism of color with the allure of a globalized good.

As privileged members of American trade, Genoese merchants shipped many tons of American dyes into Seville and Cadiz, to be distributed across Europe and beyond.Footnote 71 Merchants held specific and experiential knowledge of the monetary currency of color as they traded blocks of raw dyestuffs, the values of which fluctuated as the flow of goods waxed and waned.Footnote 72 This mercantile knowledge thus framed the Genoese understanding of the cultural significance of color within European society. Raw materials were imbued with values and meanings, which were then augmented and transformed as dyestuffs used in the fabrication of sumptuous garments. An emphasis on the materiality of color is therefore crucial to comprehend the qualities signified through colorful clothing for a sartorially-minded society.

In her portrait, Elena is sheathed in an expanse of inky black cloth. This places her within an extensive visual tradition of black-clad merchants and aristocrats, eager to convey specific moral and social qualities through their clothing. Indeed, the effectiveness of the garments in these images—or at least those painted after American trade began—is largely due to the use of the dyestuff known as logwood. Imported from New Spain's Campeche Bay, the fermented bark of the logwood tree was highly successful as a black dye and arguably fed the European craze for black clothing. Indeed, most of Van Dyck's Genoese portraits—painted after the introduction of logwood to Europe—portray the sitter enrobed in lustrous black silk taffetas, satins, and velvet for both official robes and lay garments. Thus, it can be strongly posited that Elena's painted garments represent logwood-black textiles.

While black fabrics had been achievable before the importation of logwood, a good black color could only be produced through a complex, time-consuming, and costly process. Raw cloths were repeatedly submerged in a vat of woad or indigo to achieve a dark blue, then were topped with yellow weld or reddish madder, both of which required a mordant to bind the dye to the cloth. Logwood vastly simplified this process. Raw fabrics only required treatment with iron sulphates before dyeing with fermented logwood.Footnote 73 This resulted in a fast, saturated black that outplayed any other black on the market, both for its material and symbolic qualities.

As John Harvey has posited, “it was Spain, more than any other nation, that was to be responsible for the major propagation of solemn black both throughout Europe, and in the New World.”Footnote 74 The triumph of black represented a shift in the aesthetic and ethical paradigms of the period, as black clothing came to exemplify the classical rule of unum et simplex, unity and simplicity.Footnote 75 Black garments imitated classical principles of nature, namely coherence and unity, order, proportion, measure, harmony, and symmetry. This came to typify refined elegance and moral superiority without contrivance or affectation, so defined in the widely read etiquette manual of Italian writer and courtier Baldassare Castiglione (1478–1529), Il Cortegiano (The courtier, 1528).Footnote 76

The inception of Europe's obsession with black clothing can be traced back to the fashionable and influential Burgundian court of Phillip the Good (r. 1419–67), where it was increasingly associated with political and moral authority.Footnote 77 As such, the Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs embraced the trend, “using it to proclaim their temporal and religious hegemony in Europe.”Footnote 78 In Spanish writer Juan Rufo's Las seiscientas apotegmas (The six hundred apothegms, 1596), black was deemed “the most honest color”; in 1627, Gonzalo Correas proclaimed that “in dress [it is] an honorable color in Spain.”Footnote 79 Under Charles V (r. 1519–56), who was particularly fond of the hue, black cloth represented “imperial power [and] a sober gravity consonant with the virtues of temperance and moderation.”Footnote 80 It follows that Charles and his successors, and Spain's agents (including the Genoese) would adopt the fashion for black, marking their allegiance through sartorial signifiers. As such, throughout the sixteenth century black clothing became synonymous with the characteristically Spanish adherence to tradition, modesty, and Christian honor.Footnote 81 However, black did not solely diffuse via a top-down process from the court. As Harvey notes, Philip II of Spain (r. 1556–98) appeared to his contemporaries as a man “who looked very ordinary, dressed in black just like the citizens . . . that is, like a merchant.”Footnote 82 And indeed, both the Dutch Republic and the Republic of Venice were home to notably black-clad merchant societies. Black dress could thus be both courtly as well as mercantile and urban, marking it as the perfect attire for Europe's merchant elite.

Importantly, black clothing was not solely the remit of Spain. The craze for black reached its zenith during a period of fierce religious warfare between Catholics and Protestants, and was especially pronounced among Spain's enemies, namely England and the Northern Netherlands: “having been the uniform of Spanish Catholicism, black was to become, complementarily, the uniform of anti-Spanish Protestantism.”Footnote 83 Considering the all-consuming nature of Europe's wars, both sides organized themselves into “institutional machines” and adopted a black uniform, in a display of discipline and “ascetic self-effacement.”Footnote 84

Black was thus a malleable color whose symbolic power could be harnessed by diverse groups. For the Genoese, there was a double incentive to adopt the color; it assimilated the nobility with a larger, Europe-wide elite, while as associates of the Spanish Empire, black clothing also established visual and material links to Spanish Catholicism, ideals of gravitas, and the Crown's increasingly global authority. These connections to Spain were especially important for the Cattanei and Grimaldi, as families with strong Spanish political and economic ties. Clothing dyed with American logwood materialized the complex intertwining of the two polities, while also nodding to the sobriety expected at the Spanish court.

Black was particularly favored among women; this predilection is reflected in Genoese sources. An inventory of the goods belonging to nobleman Geronimo Serra (ca. 1547–1616) from 1617 lists for his daughter Maddalena a black velvet camiscietta grande alla spagnuola (a formal gown composed of a sleeved bodice and skirt) with woven black and white ornamentation; another camiscietta in printed black satin with black and white embroidery; and a camiscietta in black buratto, a finely-woven silk and wool blend, lined with taffeta.Footnote 85 An anonymous inventory from 1623 records black garments of varying age and quality. It lists a set of skirts in black shorn velvet, along with an old black damask ungaresca, or jacket; a black shorn velvet ungaresca and matching skirt; an ungaresca and skirt in cloth of silver and black; and a black taffeta ungaresca and skirt with slashing.Footnote 86 Similarly, in her will from 1635, noblewoman Vittoria Spinola left her best ungaresca in black baietta cloth to her cousin Geronima.Footnote 87 Being of similar rank to the women cited above, it can be safely assumed that Elena also owned an array of black garments, likely resembling those pictured in her portrait.

The popularity of black clothing among European women can be attributed to its symbolic and aesthetic valences. The materiality of black cloth—and especially of black silks—was highly prized; it was an excellent vehicle for displays of gloss, luster, and sheen, qualities which were ascribed meanings of rarity, variety, value, and beauty.Footnote 88 For elite women, black clothing was a powerful visual foil for pale, rosy skin with a clear luminosity. When clothing was constructed from glossy silks, the effect was amplified. Like an expensive silk, as poet Agnolo Firenzuola (1493–1543) declared, beautiful skin had a “luster,” and was “shiny like a mirror.”Footnote 89 Good coloring was more than an attractive beauty feature, however; it also signaled internal health, strength and stability of the mind, personal and religious virtue, and nobility of spirit, all of which were essential for aristocratic women. These notions were founded in Galenic medical theories and asserted that a well-colored face best reflected a healthy balance of the humors.Footnote 90 As women's social currency lay in their health and ability to bear children, shining, lustrous skin reflected their bodily health and noble blood. As Erin Griffey notes, “Within the context of elite marriages, the bride's complexion was widely scrutinized because beauty, health, and fertility were all intrinsically connected.”Footnote 91

Given the importance of radiant skin to the conveyance of these crucial qualities, fairness was best expressed through direct juxtaposition with blackness. In her portrait, the color of Elena's silk clothing highlights her glowing complexion through the dramatic chiaroscuro of her shining face and long, pale fingers against her black gown. Although already a mother to two children, and potentially pregnant with her third when she sat for Van Dyck, Elena's role as a producer of heirs was no less important.Footnote 92 The beholder is thus invited to make favorable connection between the lustrous black silks and the wearer's beauty, health, and nobility of character, seen in her bright, unblemished skin. For women, then, globalized fashion materials like black silk allowed them—and their portraitists—to highlight their inner qualities in a dramatic and meaningful way.

While today Elena's garments appear to be a brown-black hue, indicating that lower quality dyes were used, this is due to abrasions on the painting's surface.Footnote 93 A similar, and better-preserved, textile can be seen in Van Dyck's Portrait of a Genoese Noblewoman and her Son, painted between 1625 and 1627 (fig. 3). The slashed black satin of the sitter's skirt is glossy and rich, reminiscent of the deep, lustrous black achieved with logwood dye. A glimpse of the original color and texture of Elena's gown is visible, however, in the well-preserved passage to the left of the hand holding her skirts (fig. 2). The striking chromatic contrast of deep black pigments and dove grey highlights used to pick out the pattern of the gallon trim gives an impression of the blue-black luminosity of Elena's garments as they would have originally appeared. As such, her logwood-dyed black attire not only points to the luxury of material pleasures, but also situates the wearer of such attire within a larger network of global trade and artisanal innovation. The tactile and alluring depiction of sumptuous silks in a portrait produced for a noble silk-merchant family is thus paramount to the expression of a familial identity that was bound up in the dynamism and influence of global fashion systems.

Figure 3. Anthony van Dyck. A Genoese Noblewoman and Her Son, ca. 1625–27. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

AN INIMITABLE RED

Above Elena's head appears a radiant scarlet parasol. Like Elena's black clothing, the parasol is tinted with one of most powerful colors in early modern Europe. Red symbolized luxury, authority, and majesty. Another American dye, cochineal, compounded these concepts with the allure of worldliness and novelty, becoming both a “symbol and a commodity.”Footnote 94

Although it is not worn on her body (apart from her red cuffs), Elena is visually associated with the material currency of the vibrant reds produced with cochineal through her parasol, which serves to reinforce notions of exoticism and luxury. The centrality of accessories to the creation of effective sartorial messaging is even more explicitly conveyed as the figure of Elena overlaps her parasol. As such, her integrated biological and sartorial bodily parts are represented as “both integral to the subject's sense of identity or self, and at the same time resolutely detachable or auxiliary.”Footnote 95 Through Elena's dressed body and its associated accessory, the portrait expresses the fundamental role of precious foreign goods in the construction of sartorial spectacle and the expression of cosmopolitan prestige.

Cochineal was, after silver, the largest American export good to arrive in Europe.Footnote 96 The dyestuff produced a range of shades from pinks to crimsons and purples. What exactly cochineal was, however, remained a mystery to Europeans. The Spanish created an impenetrable veil of secrecy surrounding the substance to protect their monopoly on production. As is known today, cochineal is an insect that is parasitic to nopal cacti. For nearly two thousand years, this immensely valuable material had been used as tributes, tithes, medicine, and cosmetics by the Aztecs. Cochineal was incredibly labor intensive to harvest but the range of reds produced was unsurpassable. The chromatic effects it produced brought Spaniards in the Americas to express their admiration of “the range of red-dyed fabrics available in local markets, comparing them to the silk markets of Granada, only bigger.”Footnote 97

The letters exchanged between Spanish merchant Simón Ruiz and his agents lay out the Genoese involvement in the distribution of American cochineal across Europe.Footnote 98 Writing on 7 April 1581, Baltasar Suárez recounted that cargo was traveling from Lisbon to Genoa on the ship of Genoese merchant Domingo Justiniano. From there, the goods were to travel to Baltasar Chitadela in Lyon.Footnote 99 On April 21, Suárez wrote that Justiniano's ship, which was believed missing, arrived in Livorno, and the cargo—which was American cochineal—was to be inspected for quality before distribution.Footnote 100 Similarly, a letter written by Genoese Ambrosio de Usodemar in the early seventeenth century details how “in the possession of Esteban Scuarzafigo is half of the three thousand barrels of cochineal coming from Nicolao Nicolà and Tommaso Doria and Co.”Footnote 101

On an international scale, cochineal represented a bifold system of values that directly correlated to the commodity chain established from New Spain to Europe. The scarcity of these small, dried insects, and the high prices they demanded, marked cochineal as a socially important good. To indicate its value, at times the cost of the cochineal dye was double that of the undyed cloth. Importantly, cochineal was a particularly effective dye for animal-based textiles like silk, which thus represented a compounding of material values in a single object. Given the chromatic richness of Van Dyck's rendition, Elena's parasol is arguably intended to imitate the brilliance of cochineal dyed silk. It is perhaps a taffeta, indicated by the subtle sheen of the cloth. As such, the parasol is ideal for a display of social capital facilitated through the cultural associations of red with power and status.

The importance of Elena's parasol is not limited to its suggestion of the cochineal-dyed silks. The object held royal and exotic connotations. Depicted in ancient Egyptian wall paintings and Greek figured vases, honorific parasols were held by servants over the heads of monarchs as a mobile canopy of state. By the early modern period, parasols were considered luxury items that signaled the user's prestige through allusions to the opulence of ancient rulers.

Michel de Montaigne (1533–92) stated in 1580 that parasols had been in use in Italy since antiquity.Footnote 102 During his travels in Lombardy in 1611, English traveler Thomas Coryat (ca. 1577–1617) remarked that parasols of leather were used as protection against the sun's heat: “[that] which they commonly call in the Italian tongue umbrellas, that is, things which minister shadow unto them for shelter against the scorching heate of the sunne. These are made of leather, something answerable to the forme of a little canopy, & hooped in the inside with divers little wooden hoopes that extend the umbrella in a pretty large cornpasse.”Footnote 103

Yet unlike Coryat's description, Elena's parasol is not made of leather but a lighter silk fabric that glistens in the sunlight. Van Dyck has combined thinned and scumbled white paint with heavier daubs and trails to mimic the effect of light hitting the fibrous silk. A similar technique is visible in the crimson watered silk skirts of Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio, painted by Van Dyck in 1625 (fig. 4). Furthermore, Elena's parasol is edged with a fluffy velvet trim, executed with impasto brushwork to echo the three-dimensionality of velvet pile (fig. 5). On an actual parasol, passementerie further compounded the cost, and thus the social currency, of the item. As such, the wealth of information signified through Elena's dress is stretched across other elements of material culture in the picture plane that are associated with her person. Indeed, as the parasol is operated by her servant, he is similarly associated with it; yet as its operator, he is excluded from the user's higher-status positioning. Consequently, the object's agency remains with Elena.

Figure 4. Anthony van Dyck. Portrait of Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio, ca. 1623. Courtesy Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Uffizi Galleries, Florence.

Figure 5. Anthony van Dyck. Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, detail of parasol, 1623. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Curiously, however, Elena's face remains unshielded from the sun. Her face seems to hold its own inner light, which radiates across the picture plane. A literary reading deciphers this element of the composition. Elise Goodman brings this passage of the painting into dialogue with contemporary poetry in which women are praised through comparison with the sun.Footnote 104 In his laudation of his noble patroness, Torquato Tasso (1544–95) declared: “No glory and no grandeur are lacking in nobility of blood, in which beauty flowers in a high degree and shines like the sun.”Footnote 105 These sentiments were known in Genoa, as nobleman and Elena's contemporary Anton Giulio Brignole-Sale (1605–62) meditates upon the lovely cheeks of a woman, where “a sun blossoms.”Footnote 106 Like these women, Elena's beauty emanates light, rendering her parasol ineffective. Paradoxically, the shade of the parasol falls upon the dark complexion of the attendant who becomes her shadow, a pictorial counterpart to her luminous beauty. This follows from a well-known artistic and literary conceit, described as such by French writer Brantôme: “an excellent painter who, having executed the portrait of a very beautiful and pleasant-looking lady, places next to her . . . a moorish slave or a hideous dwarf, so that their ugliness and blackness may give greater luster and brilliance to her great beauty and fairness.”Footnote 107 As such, the parasol is key to untangling the painting's meditations on light and beauty as well as the racialized contrasts that are constructed in the composition.

Most notable about Elena's parasol is its material composition in the painting. As Barbara C. Anderson argues, “although the main European interest in cochineal was as a dye for textiles, this function also seems to have been a path to its use in painting in the form of lake pigments.”Footnote 108 Along with American cochineal, red lake pigments could be made from a variety of dyestuffs, including European kermes and lac insects, as well as plant-based dyes like brazilwood and madder. Identifying the origins of a particular substance present in lake pigments is challenging for conservators, even with the latest methods of analysis.Footnote 109 However, as these substances were used to make painters’ materials, in some early modern paintings “the dye that would have actually colored such textiles is also the one that depicts them.”Footnote 110 For cochineal specifically, Jo Kirby notes that “it is no coincidence that carminic acid–containing lake pigments only occur after the arrival of New World cochineal in Italy . . . to the point where identification of the use of such pigments becomes routine.”Footnote 111

Anderson has demonstrated that Van Dyck used lake pigments during his Italian period, which were very likely cochineal-based.Footnote 112 Indeed, technical analysis of the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo has confirmed that Van Dyck painted the parasol by applying a red lake glaze over a thick underpaint of vermilion and lead white, yet the specific pigments used to color the lake remain undetermined.Footnote 113 Nonetheless, the presence of cochineal in Van Dyck's other Genoese works strongly indicates that the pigment was used for the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo. The painter's use of cochineal lake pigments may also betray his admiration of Venetian painting, as “a genius use of and reliance on red lake pigments is also characteristic of Venetian painting.”Footnote 114 Painters including Titian (ca. 1506–76), Veronese (1528–88), and Tintoretto (1518–94) used cochineal red lake pigments in their works, and may have acted as technical as well as compositional sources for Van Dyck.Footnote 115

Importantly, the process for making lake pigments deepens the links between textiles and painting. Lake pigments were made by first dyeing strips of cloth, commonly silk (upon which cochineal was particularly effective), then extracting the dye from the dyed cloth submerged in water.Footnote 116 This was not an unusual practice; as Kirby notes, “until well into the seventeenth century, probably most kermes and cochineal lakes were made . . . [from extracting] the colorant from weighted dyed silk.”Footnote 117 As such, in some cases the presence of silk fibers on a painted canvas is a potential indicator that cochineal lake pigment has been used.Footnote 118

Artists favored lake pigments for their translucency and luminous quality, which, when used to depict textiles, brought a inimitable effect of lifelikeness to an artwork.Footnote 119 When applied over another pigment like vermilion (made from the mineral cinnabar), the effect was extraordinary, as artist Karel van Mander (1548–1606) noted in his treatise on painting, Het Schilderboeck (The book of painters, 1604): “To weave cloth beautifully [that is, to paint cloth beautifully] apply yourself to skillful glazing, which helps in the make of velvets and beautiful silks, when a glowing translucent effect is needed.”Footnote 120 The use of cochineal in painting also tied the value of the artist's hand to the material itself. As Roger de Piles (1635–1709) recommended in Les premiers elements de la peinture pratique (The first rules of painterly practice, 1684), this technique should be employed “for the most beautiful and economical results, in the process ensuring that an upper layer of cochineal lake left the most expensive materials in the hands of the master, rather than his assistants, who commonly painted in the cheaper lower and middle layers.”Footnote 121 Moreover, by the beginning of the seventeenth century, American cochineal “was already beginning to be esteemed for its provenance as well as its properties.”Footnote 122 As the son of a silk merchant, and a fashion lover himself, Van Dyck was undoubtedly aware of the significance and origins of cochineal in textiles, and expertly translated this into his painting.Footnote 123 Elena's resplendent parasol may have thus been consciously employed in order to augment the status of the sitter through these connections with the luxury item of cochineal.

Through technical analysis, cochineal-based lake pigments have been found in other paintings from Van Dyck's oeuvre. Of his Genoese works, the red lake pigments used in The Balbi Children (ca. 1625–27) have the same characteristics as the cochineal red lake observed in Charity, painted after his return to Antwerp between 1627 and 1628.Footnote 124 On this basis, it can be assumed cochineal was very likely used by the artist in Genoa.Footnote 125 This group portrait is a vibrant celebration of the color red and its materializations in cloth (fig. 6). Likely painted for the de Franchi family, who were members of Genoa's new nobility, The Balbi Children conveys the importance of luxury materials to the crystallization of the family's relatively new elite status. The portrait depicts two of the three children bedecked in sumptuous red clothing. The leftmost boy wears an astounding suit covered in silvery-gold piping with a cape woven with silver thread and matching hose. On the right, a younger child still in their leading strings wears a red gown with gold gallon trim. The outfits of both children have been worked up with vermilion and finished with red lake glazes.Footnote 126 Upon closer regard, the shades of red between the children are different; one outfit is slightly more orange in tinge, while the other is bluer. The subtlety with which Van Dyck differentiated these tones may be lost on modern audiences, but for the early modern beholder, the range of colors depicted would have been immediately discernible. Moreover, Van Dyck has reflected these tones in the dramatic swag of shot velvet drapery suspended behind the children. As noted by Ashok Roy, the drapery was layered with a deep crimson lake, likely prepared from cochineal.Footnote 127 Indeed, Van Dyck's use of red lake glaze is more extensive than is seen in his earlier work, and such a technique is not common in his later oeuvre.

Figure 6. Anthony van Dyck. The Balbi Children, 1625–27. © The National Gallery, London.

In the absence of typical Baroque crimson drapery, Elena's parasol acts as an aggrandizing textile backdrop that highlights one of the most significant globalized goods ever to reach Europe's shores. Although the source of the red dye used in the glaze remains unknown, Van Dyck's other Genoese works very likely carry cochineal lake pigment on their surfaces. It is thus not unfounded to assume that the artist also used cochineal lake glazes for the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, thereby imbuing the painting with both symbolic and material meanings. Yet even if cochineal is not present, the parasol has been painted in a manner that imitates the dazzling chromatic effects that cochineal-dyed silks produced, indicating the social, economic, and cultural value of luxury global goods to the Genoese elite.

CLOTHING DIFFERENCE

The figure of the Black servant in the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo has been consistently marginalized by art historians. Scholars have been content with tracing his compositional source to Titian's Portrait of Laura Dianti (1520) and citing his pointed ears and generalized features as evidence of his invention by Van Dyck.Footnote 128 The analysis of literary scholars has yielded more fruitful results; Peter Erickson situates the painting in historiographical discussions of race, and interprets the portrait in relation to the visual regimes that influenced and reflected power relations between white sitters and Black attendants.Footnote 129 Indeed, since the 1980s discourse surrounding the presence and representation of Black people in European art has developed substantially.Footnote 130 Nonetheless, Elena's attendant is commonly sidelined in discussions of the interconnection of artistic production and the broader historical trends that shaped early modern Europe. While The Image of the Black in Western Art series does much to bring visibility to Black figures in early modern art production, when discussing the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, analysis largely ends at the seemingly inevitable, and euphemistic, “presence of a favored black attendant” in a “splendid state portrait.”Footnote 131 This shortsightedness is unfortunate. Attention must be recentered on the Black attendant—regardless of whether he is a purely invented figure or a real person—to examine the ways in which Europe's material culture referred to the real, complex experiences of Black Africans in Europe.

The depiction of Black African servants, attendants, or pages in portraiture was a widespread artistic trend across Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Indeed, the trope was legitimized and formally recognized by Samuel van Hoogstaten (1627–78) in his art treatise Inleyding tot de Hooge Schoole der Schilderkunst (Introduction to the noble school of painting, 1678): “the eye finds it . . . a pleasure sometimes to add a Moor to a maiden,” in order to enliven a portrait.Footnote 132 This pictorial motif stemmed, however, from an increased presence of Black Africans at Europe's courts. As Francisco Bethencourt rightly asserts, these figures were predominantly pictured in the roles they occupied in Europe, namely “servants, soldiers, musicians and laborers.”Footnote 133 The visual role played by Black Africans was largely negative, based on unforgiving stereotyping that cast them as crude, malicious, lazy, licentious, or unintelligent. Yet these debasing traits were also “always challenged by their representation in spirited or elevated human form,” thus reflecting the multifaceted attitudes and perceptions of Africans in the European imaginary.Footnote 134 While certain Black Africans rose to some prominence at court, “these special cases [were] defined by the ambivalence between prejudice and paternalism, inferior position and social achievement, social values and transgression.”Footnote 135 This sentiment exemplifies the situation of the Black attendant in the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo. Like these real-life figures, Elena's servant functions, in Bethencourt's words, as a “luxury accessory” and is exhibited as a strange phenomenon of the natural world.Footnote 136

It is also vital to note that many of the Africans at court were enslaved.Footnote 137 For Fernand Braudel, this retention of slavery was a pronounced feature of Mediterranean societies in particular: “It was the sign of a curious attachment to the past and also perhaps of a certain degree of wealth, for slaves were expensive, entailed responsibilities and competed with the poor and destitute.”Footnote 138 Italy's courts demonstrated a fascination with dark-skinned enslaved attendants. One early and particularly jarring example is found in the writings of Isabella d'Este (1474–1539), Marchioness of Mantua, who, in a letter to her agent in Venice from May 1491, instructed him to find a child as young and as Black as possible. By June of the same year, she had acquired an African girl of fourteen, stating that “we could not be more pleased with our black girl even if she were blacker.”Footnote 139 Such an account showcases the social value of exotically dark-skinned attendants, as well as the ambivalent attitudes faced by some Africans who encountered Europe's courts.

Whether Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo owned or employed a Black African is yet to be determined. This possibility should not be ruled out, however, as both the Grimaldi and Cattaneo had long histories of purchasing enslaved people. The Liber sclavorum (Book of slaves), which lists enslaved people and their owners for the year 1458, records thirty-three Grimaldi members who owned fifty-six enslaved people between them. Similarly, the Cattaneo albergo owned fifty-five, placing both families as some of the largest buyers of captives.Footnote 140 Nonetheless, it remains unclear whether the Black attendant in the portrait—painted 150 years later—represents a free or enslaved worker.

Current scholarship indicates that written sources on enslavement are richest for the medieval period.Footnote 141 Domenico Gioffrè's qualitative and economic survey of the fifteenth century provides crucial data on the ethnicities, ages, genders, and prices of enslaved people in Genoa.Footnote 142 Of more than 1,600 notarial acts collected for the fifteenth century, Gioffrè finds only ten references to Black captives, suggesting either their minimal presence in the city in this period, or a lack of detail in the records.Footnote 143 Unfortunately, Gioffrè's work muddies the waters, as he frequently groups Black enslaved people with Moors from North Africa and Canary Islanders, leaving little room for precise analysis. Scholarship on the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is much less developed, due in part to the paucity of sources from this period. Luigi Tria's study on slavery in Genoa reproduces 113 documents from 1184 to 1691, of which only nine date from the seventeenth century. Of these, Turkish is given as the most common ethnicity for the enslaved people mentioned.Footnote 144 More recently, Giustina Oligiati and Andrea Zappia's catalogue Schiavi a Genova e in Liguria (Slaves in Genoa and in Liguria), which accompanied an exhibition at Genoa's State Archive in 2018, reproduces 138 documents. Of these, only six date from 1550 to 1650, and similarly, Turkish enslaved people are most frequently mentioned.Footnote 145 None of the sources in this volume mention enslaved Black Africans, suggesting a decrease in their already small numbers during this period.

This deficit of sources is puzzling. Documents may have been lost, as Genoa suffered significant damage during the French bombardment of 1684. Available sources may also reflect a decline in the city's ethnic diversity in the seventeenth century.Footnote 146 The population of enslaved Black people may have decreased in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, as this commerce became increasingly displaced to the Iberian Peninsula, the West African coast, and the Americas, reducing the availability and increasing the price of captives in Genoa. It is thus possible that the Black servant in the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo represented a rare aspirational good for the commissioning family, recalling the exotic splendor of Europe's courts. A painting such as this presents numerous knots for historians to address, which may only ever be partially resolved.

The Black attendant is, however, more than a nod to courtly practices and pictorial traditions. Both the Grimaldi and Cattaneo had been implicated in the Atlantic slave trade for over a century at the time of the portrait's painting, and scholarly interpretations must take this into account. By the first decade of the sixteenth century, which Toby Green pinpoints as the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade, Genoese traders were transporting enslaved people from the West African coast to Cape Verde, then on to Europe and the Americas.Footnote 147 As early as 1513, Juan Francesco Grimaldo and his business partner Gaspar Centurión, both based in Seville, were shipping enslaved Africans to the island of Hispaniola. The Cattaneo clan dealt almost exclusively with enslaved people during the sixteenth century, and one branch of the family had settled on the Cape Verde Islands.Footnote 148 In 1519, Caesar Cattaneo, a distant relative of Elena's husband Giacomo, had his will drawn up in Genoa; it recorded that his son Antonio had died in Cape Verde, and that his other son Alessandro was also resident there.Footnote 149 Nicolo Cattaneo (ca. 1480–1554)—another distant relative of Giacomo Cattaneo—resided in Seville, and in 1515 was granted permission to live in Santo Domingo and trade enslaved people there. In June of that year, Nicolo bought an enslaved Guinean from Francisco de Garay, governor of Santo Domingo, for 13,000 maravedís. Nicolo's actions exemplify the Genoese prioritization of commerce, as he immediately placed the enslaved person back on the market for sale in the Americas. By the 1540s, Nicolo owned a ship with Visconte Cataño named La Trinidad, which carried enslaved Africans to the Americas and Caribbean.Footnote 150 At this time, as Ruth Pike observes, enslaved people (along with manufactured goods) “became the basis of Genoese trade with America.”Footnote 151 The Genoese maintained this commerce, if not increased its intensity, as by 1663, Genoese bankers Domingo Grillo, Marquis of Clarafuente, and Ambrosio Lomelin secured a seven-year asiento from Philip IV of Spain (r. 1621–40). This agreement granted them a monopoly on the trade of enslaved Africans to Spain's American colonies following the Portuguese revolt of 1640, which had stifled trade.Footnote 152 It is thus highly likely that, at least until this point, the Grimaldi and Cattaneo also maintained their ties to this lucrative trade. With this important contextual information reasserted, the Black African in the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo becomes not solely an ornamental figure in the painting, but an abstraction that points to the entangling of the Grimaldi and Cattaneo in the movement of enslaved Africans from the West African coast across the Atlantic.

Whereas enslaved people were viewed as essential fodder for the burgeoning American economy by European colonialists, in the Mediterranean world they were a luxury good to be bought and sold alongside other global commodities. As Steven Epstein asserts, domestic servant roles were occupied in Genoa by the local poor, who were paid in food and clothing in a similar renumeration system to enslaved people.Footnote 153 To own an enslaved person, then, was purely a question of social standing. As is demonstrated in a record from 1626, a nineteen-year-old Turkish boy named Mohammed was bought for 600 lire by nobleman Giorgio Doria.Footnote 154 The mammoth amount paid for Mohammed was more than the annual salary of a chancellor of the Republic.Footnote 155

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Genoese elite would not have necessarily made a synecdochic connection between Black Africans and the concept of slavery.Footnote 156 Throughout the medieval period and well into the sixteenth century the Genoese traded captives who were predominantly Turkish, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Circassian, or Tartar.Footnote 157 Indeed, the preference for light-skinned enslaved people was such that darker-skinned captives routinely summoned lower prices in Europe during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.Footnote 158 From the middle of the sixteenth century onwards, however, and as is seen through the example of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, this preference shifted, influenced by courtly tastes for curiously dark skin. The bodies of enslaved people were highly valued, and, thanks to courtly trends, dark-skinned enslaved bodies were prized for their exotic novelty. In short, their financial value was intrinsically tied to, and augmented by, a high cultural value.

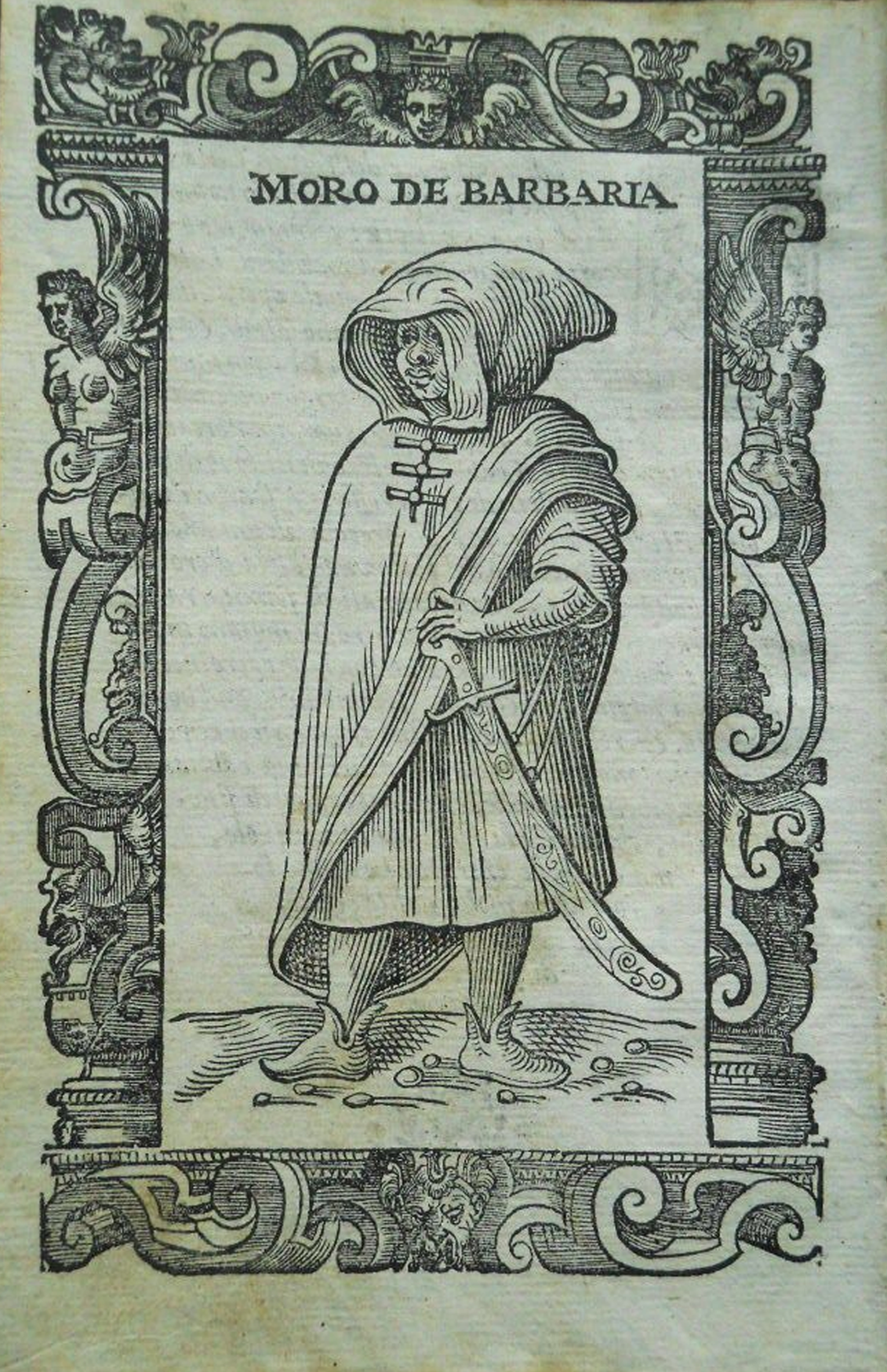

In the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, this high cultural value is set forth through meaningful clothing. In contrast to Elena's heavy black Spanish styles, her servant wears an airy Eastern-style tunic with frogging.Footnote 159 The form of his garment recalls contemporaneous depictions of Moorish, Turkish, and Ethiopian men that exhibit the messy merging of distinct groups by European artists.Footnote 160 This visual typology is indebted to costume books from the sixteenth century, which illustrated national or ethnic identities in a very generalized way. However, these images are typically more flamboyant or exaggerated with their garment form and accessories. In Cesare Vecellio's Degli habiti antichi e moderni (Of costumes, ancient and modern, 1590), the “Moro di Barbaria” wears a frogged tunic with a voluminous hood and an ornately decorated scimitar (fig. 7). In Abraham de Bruyn's Habitus variarum orbis gentium (The costumes of the various peoples of the world, 1581), the male Ethiopian most closely resembles Elena's servant, though he wears a full turban and carries a bow, dagger, and sword (fig. 8). This trope is repeated in Hans Weigel's Trachtenbuch (Costume book, 1577), which depicts a Moor from Arabia decked out in a voluminous hood and mantle, tunic, and scimitar at his side (fig. 9). Even Van Dyck's mentor Rubens sketched a similar figure, who wears a frogged and hooded tunic, pointed boots, and scimitar (fig. 10).

Figure 7. Cesare Vecellio. Moro di Barbaria in Degli habiti antichi e moderni di diverse parti di mondo, 1590. Woodcut. © Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Figure 8. Abraham de Bruyn and Jean Jacques Boissard. Ethiopian Man. In Habitus variarum orbis gentium. Habitz de nations estranges, 1581. Engraving. © Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Estampes et photographie, 4-OB-2, fol. 67.

Figure 9. Jost Amman. Moor from Arabia. In Hans Weigel, Habitus praecipuorum populorum, Trachtenbuch, 1577. Woodcut. © The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, L.11.33, plate 176.

Figure 10. Peter Paul Rubens. Four Figures in Oriental Dress. In the Book of Costumes, 1609–12. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London.

These images also highlight how non-European ethnicities and cultures could be conflated in the European imaginary. The largest sections of costume books illustrate the minutiae of local European fashions as they appeared in different cities, yet the sections picturing dress from elsewhere diminish in size, resulting in the conflation and generalization of styles.Footnote 161 This phenomenon is exacerbated by the fact that image plates were recycled and interchanged between texts, and in the process could lose their original significations.Footnote 162 For Europeans, then, men from North and West Africa, the Middle East, and the eastern Mediterranean—whose identities were inexorably bound with the constant threat of Islam—were visually and thus culturally equated with one another through easily recognizable, though obviously non-Western, garments, regardless of physiognomic difference between wearers.

Van Dyck was undoubtedly familiar with these or similar images and drew from them for inspiration for the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo. Importantly, costume images frequently depict Moorish and Turkish men with supplementary sartorial elements—swords, turbans, hoods—that have been removed from Elena's servant. He instead holds her parasol, which draws a direct line to Elena's face. It is thus likely that Van Dyck consciously forewent a hood or turban for the African servant, as these accessories would have interrupted this crucial axis and shifted the visual center of the composition. Moreover, the replacement of a weapon with a textile accessory casts the figure in a non-threatening light befitting his subservient place in the portrait.Footnote 163

When Eastern garment forms were worn on dark-skinned bodies, the image conjured up in the Genoese imaginary was likely that of not only enslaved Black Africans in the Atlantic world but also those in the Byzantine and Ottoman lands.Footnote 164 Greek historian Laonicus Chalcocondylas's (ca. 1430–70) Histoire générale des Turcs (A general history of the Turks) gives an insight into the visibility and desirability of enslaved Black people in the Ottoman Empire: “The pashas and other chiefs of the port of the Lord all have slaves. Several of them, out of curiosity, have Moors, as do some Frenchmen, whether because of their strength or the tendency to assign greater value to those things that are the least familiar.”Footnote 165 Considering the Genoese presence in Constantinople, it is highly likely that they too found dark-skinned enslaved people curious and thus desirable to acquire.

Moreover, the image of the Eastern-dressed Black male accompanying a woman may have evoked a specific reference for the Genoese beholder, namely that of the Black eunuchs charged with guarding the sultan's harem at the Ottoman court (although these attendants were typically men rather than adolescents). As Genoese merchants interacted extensively with the Ottoman court, it is likely that such a figure would have been easily recognized. A gouache from an anonymous costume book entitled Costumes de la Cour du Grand Seigneur (Costumes of the court of the Grand Seigneur, ca. 1630) depicts a dark-skinned eunuch (Eunuchi mori), whose attire has the attributes of Eastern dress (fig. 11). He wears a blue floor-length short-sleeve tunic with frogging over an orange robe decorated with a foliate pattern. He also wears a white turban and holds a silver baton in hand. Although the image has not been executed by the most confident of hands, his garb resembles that worn by Elena's attendant.

Figure 11. A Black Eunuch. In Costumes de la Cour du Grand Seigneur, 1630. Gouache. © Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Estampes et photographie, 4-OD-5, fol. 5r.

The preference for Black eunuchs—who were customary at the Ottoman court by 1582—was largely tied to broader religious and mercantile concerns.Footnote 166 The Abrahamic religions forbade the enslavement of people from the same religion, leaving those belonging to other religions as the only possibility for enslavement (although in practice, Christians did indeed enslave baptized Christian converts). Thus, as George Junne notes, “the supply of slaves dried up beginning in the eleventh century as Slavic peoples converted to Christianity and the Turkish people converted to Islam. That would leave sub-Saharan Africans as the primary source of eunuchs.”Footnote 167 These captives were channeled through East Africa which, due to its proximity to Ottoman lands, meant that there was no shortage of enslaved eunuchs.Footnote 168 Black eunuchs were seen to be exceedingly loyal and were expected to be “graceful and well-made”; yet, on the other hand, the perceived ugliness of Africans was also a covetable trait which increased the price of the enslaved person.Footnote 169 Incidentally, each of these attributes—namely, loyalty, gracefulness, and ugliness—also cast African servants as ideal pictorial companions and counterpoints in courtly portraiture in Europe.

Black eunuchs were extremely costly to purchase in the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 170 At court, however, they wielded significant political power as close associates of the royal family and as guardians of the harem who controlled the sexuality of the women inside.Footnote 171 Furthermore, as they were fully castrated, they did not run the risk of engaging in sexual relations with the women of the harem and thus represented a nonthreatening alternative to only partially castrated white eunuchs. If Elena's attendant was at least partly intended to represent a eunuch, his presence can be explained by his sexual innocuousness, given the link between Black male servants and a lack of virility in the Ottoman context. This is amplified by his diminutive and servile positioning within the composition. If, then, the Black attendant is to be read in these terms, he functions to police the boundary between Elena's space and the potentially intrusive or sexualizing gaze of the viewer.

One other crucial attribute of the African servant's clothing is its perceived timelessness. His dressed body recalls not only distant lands but a distant, earlier temporal space. Giorgio Riello remarks upon this phenomenon in costume books, which relied upon “the construction of a narrative of change in which modern dress was opposed to ancient mores.”Footnote 172 Costume books, in a similar manner to the Portrait of Elena Grimaldi Cattaneo, constructed an imaginary global space in which non-Europeans existed in an unchanging time, predating that of Europe.Footnote 173 This was brought to life through clothing, which suggested that although fashions were ephemeral in Europe, dress was invariable elsewhere.Footnote 174 Through a juxtaposition between the servant's timeless Eastern dress and Elena's modern garb, Van Dyck employs this narrative of ethnocultural stasis attributed to non-European cultures.Footnote 175

The specific situation of the Genoese in the eastern Mediterranean reinforces this argument. While the Genoese had been present in the region since the early medieval period, by the seventeenth century they no longer held primacy, as the Venetians and Ottomans overtook their colonies and settlements. Considering their ever-present yet greatly diminished influence in the eastern Mediterranean, visual representations associated with Ottoman Turkey likely evoked an earlier age of the Republic's commercial supremacy in the Genoese imaginary. However, as previously mentioned, Genoa's commercial success in the seventeenth century was largely due to the increasing traffic in enslaved Africans in the West, some of whom were present in the Republic itself. As such, the figure and dress of the Black attendant distances him both geographically and temporally from seventeenth-century Genoa, while also very much situating him within this specific milieu. Oscillating between these divergent temporalities and localities, the servant collapses both time and space, suggesting an embodied reminder of the enduring global reach of the Genoese, across oceans as well as centuries.

THE MEANINGS OF COLOR

Along with the form his garments take, the color and material worn by the Black attendant can be interpreted in a variety of ways. He wears a light weave of silk, perhaps an organza over a more saturated cloth, which catches the light with shimmering, buttery highlights. The hues have been worked up on a red underground, layered with orange iron oxide and charcoal, and accented with lead-tin yellow and lead white.Footnote 176 The color of the garment immediately recalls those worn by marginalized communities in early modern Europe, such as Jews and sex workers, who were forced to wear yellow.Footnote 177 However, the multivalent nature of color renders it challenging to pin down one sole meaning. Considering the obfuscated status of Africans in Europe, it is possible that the yellow hue of the servant's attire aligns him with the social marginalization experienced by Jews and sex workers, yet further interpretation is warranted.

Given his servile status in the portrait, the Black attendant is likely wearing a livery. A sketch in Bohemian traveler Bedrich z Donín's travelogue from 1607–08 depicts a richly dressed Genoese woman carried in a litter by two servants in livery (fig. 12). Images like these indicate that contemporary dress was typically favored for servants’ attire. However, Elena's servant has been purposefully dressed in Eastern styles for their rich symbolism and evocation of a distant place and time. Nonetheless, his outfit's color resonates with the heraldry of the Cattaneo clan, which sets a black eagle against a gold-yellow ground surmounting a field of red and gold stripes. Indeed, all the dominant colors of the painting, including the cerulean sky, refer to the Cattaneo seal.Footnote 178 As such, though stylistically exoticizing, the frogged tunic can be read as a form of livery, indicating that the Black attendant is in the service of the Cattaneo family.Footnote 179

Figure 12. Bedrich z Donín. Detail of a litter in Genoa. In Pilgrimage to Holy Sites, 1607–08. © Královská kanonie premonstrátů na Strahově, DG IV 23, fol. 114.

In compositional terms, the yellow garment provides an elegant tonal harmony with the deep shade of the wearer's skin; as the pictorial opposite to Elena's black-and-white contrast, yellow and brown are chromatically harmonious. For this reason, in seventeenth-century European painting, yellow seems to have been an extremely popular color with which to dress Black Africans, from Magi to musicians, buffoons, and enslaved people. This can be seen in works by numerous Dutch and Flemish artists. To name but a few: a yellow-clad African can be seen in Jan Mijtens's Portrait of Maria of Orange with Hendrik van Zuijlestein and a Black Servant (ca. 1665); Jacob Jordaens's The Eye of the Master Feeds the Horses (ca. 1600–49); Hendrik Heerschop's The African King Caspar (1654); and Rubens's Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1618–19), which Van Dyck may have seen in Rubens's Antwerp studio.Footnote 180