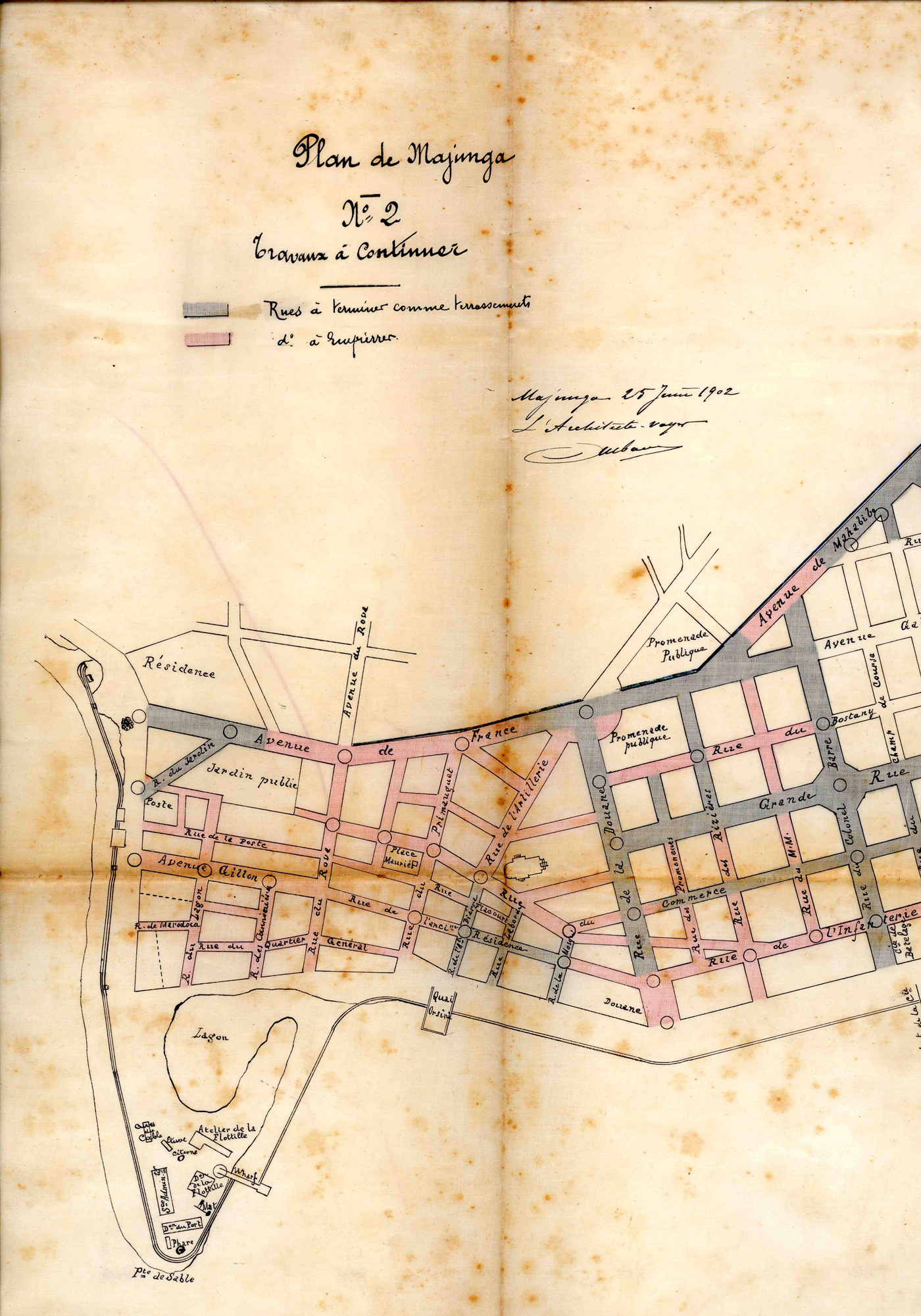

Looking from above through the aerial purview of a 1902 map, a small white square marked ‘Place Mauriès’ centres the gaze on the heart of Majunga (see Figure 1).Footnote 1 Set in the middle of a burgeoning Indian Ocean port city, Place Mauriès apparently intended to serve as a public square, a leisure space, a commemorative garden to memorialize a key French military officer, and a symbolic site of French colonial power. The unanticipated trajectory of the square, however, would eventually expose the fragility of colonial power and the indeterminacy of colonial urban plans and projects in this African city. By the 1940s, Place Mauriès had devolved into a peripheral site, rarely frequented and falling into disrepair. Shortly following Madagascar's independence in 1960, energetic efforts were taken to efface the material traces of Mauriès in the park, and to re-commemorate it after an anti-colonial activist, Jean Ralaimongo. The park was uniquely chosen as a site of post-independence transformation, even while other roads, parks and buildings in Mahajanga maintained their colonial-era names and character. Over time, the park again lapsed into dereliction, until a group of residents of South Asian descent appropriated the site in the early 2000s to revere their beloved religious leader, His Holiness Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin. Their proprietorship of the park, however, revealed the residual tensions and contestations over the parameters of belonging to the city.

Figure 1 Map of Majunga, 1902. Source: Archives National, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara.

The story of Place Mauriès (now named Jardin Ralaimongo) presents several puzzles. Why is it that some public places have been cultivated, beautified and frequented over time, while others have not? What was it that gave the successive commemorative projects of the Jardin Ralaimongo salience at the times when they were enacted? Why was Place Mauriès singled out for post-independence transformation, while other colonial-era sites kept their given names and features? And if the park's history can be understood in part as laminated layers of remembrance and forgetting, then who exactly has forgotten and neglected the Jardin across these passages of time? More broadly, how do we understand processes of decay and abandonment, and their relationship to the silencing of memory?

In Malagasy history, erasing parts of the past and retaining others has always been part of staking post-independence and transnational identities.Footnote 2 A sustained scholarly interest in memory and history in Madagascar has richly documented how narrative, ritual and embodied practices have been critical means through which ancestral, political histories are carried, continued and disseminated (Cole and Middleton Reference Cole and Middleton2001; Feeley-Harnik Reference Feeley-Harnik1991; Graeber Reference Graeber2007; Lambek Reference Lambek2002; Middleton Reference Middleton and Middleton1999; see also Sharp Reference Sharp2002; Reference Sharp2003). Invocations of the past are generationally specific, and might be understood as ‘moral projects’ that reflect individual and collective aspirations for meaningful life (Cole Reference Cole1998; Reference Cole2001; Sharp Reference Sharp2002). Tombs and rural land in particular have historically served as devices for staking lasting claims to belonging and authority, through the petitioning of ancestors.Footnote 3 But processes of historical consciousness and claim-forging are forever intertwined with effacement and compression of other histories. Some pasts – whether of ancestral genealogies or traumatic colonial violence – are necessarily and actively forgotten by successive groups in Madagascar to make room for other memories, figures and narratives (Cole Reference Cole1998; Reference Cole2001; Graeber Reference Graeber1995).

Over its 100-year history, this public square was founded, forgotten and reincarnated again and again as a memorial to a succession of revered leaders, thus serving as a kind of living spatial register of the historical socio-political changes that have given rise to the city. In this multi-ethnic and multi-confessional Indian Ocean port town of some 300,000 inhabitants, I contend that contestations over belonging have endured and been enacted over strategic sites on the urban landscape such as the present-day Jardin Ralaimongo. In considering the biography of the Jardin Ralaimongo, I try to elucidate the ways in which different socio-political groups have drawn on architectural sites to negotiate differences, frame collective memories, and legitimize their claims to the urban landscape of Mahajanga. I seek to contribute to a growing body of literature about the ways in which colonial public monuments and spaces become entangled in contestations over belonging between different ethnic, religious and class groups in post-independence African contexts.Footnote 4

This study builds on scholarship around memory, place and authority in Madagascar,Footnote 5 but also departs from it by bringing these insights into conversation with colonial monuments and urban built environments. The case of the Jardin Ralaimongo, I argue, is important in that it exposes the active, formative roles of urban sites and built forms in shaping the workings of memory, historical consciousness and claim-making. Within the vibrant literature on historical consciousness and ritual practice in Madagascar, however, less attention has focused on the mechanics of silence, recollection and belonging in everyday, urban spaces. One wonders how might the urban, built environment shape that which can be invoked, celebrated and effaced? If the urban cityscape is a text that can be both read and written, then what material conditions enable us to see, recollect and enunciate the past? How does the city's built environment shape why, when and by whom some pasts are remembered while others are forgotten?

Using a spatial lens, I show how, as city inhabitants have reworked the spaces of the garden, so too has the park itself – through its layout, material artefacts and location within the city – constrained the possibilities of what can be remembered and forgotten, and who can be brought together, in contemporary times. Places have not merely been instrumental or passive recipients of inscriptions; rather, the material residue of the park has afforded some possibilities for claim-making and has limited others. The neglect and decay of the park, moreover, might be understood as cumulative, active gestures towards managing the obstinance of enduring material relics. As some groups left the bronze and stone obelisk that adorned Place Mauriès to fall into disrepair, their actions effectuated a silencing of some pasts. Material traces of the colonial past, I suggest, are not always reworked into local constructions of belonging, but are sometimes best forgotten by neglecting them. The story of the Jardin Ralaimongo thus complicates narratives of declineFootnote 6 – which contend that humans have destroyed or neglected urban environments – that characterize much public rhetoric around urban decay, city planning and heritage protection in post-independence African cities. Neglect and decay can also be sometimes understood as active processes of disconnecting, forgetting or perhaps suppressing the past, rather than the consequences of insufficient material, technical and knowledge-based resources.

Situating Place Mauriès

Like other coastal East African and Indian Ocean towns, the spatial unfolding of Majunga emerged as a kind of palimpsest. Past knowledge, aspirations, religious practices, technologies and aesthetic sensibilities from staggered groups of Malagasy,Footnote 7 Antalaotra,Footnote 8 East Africans, South Asians, Yemenites, Comorians and Europeans were etched as material traces on the urban landscape (Vérin Reference Vérin1975; Gueunier Reference Gueunier1994).

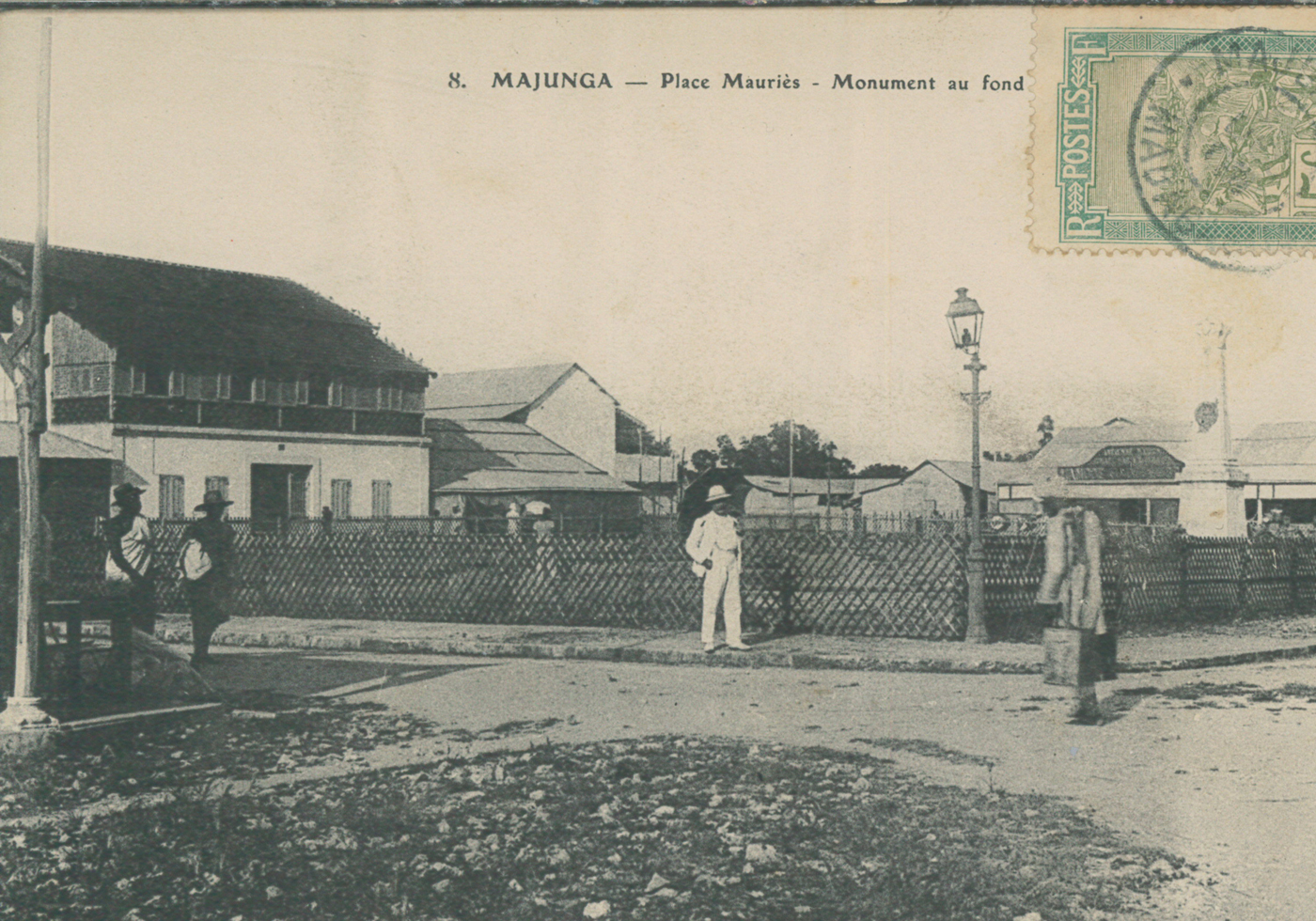

Beginning in the eighteenth century, Majunga grew under a SakalavaFootnote 9 monarchy into a vibrant, cosmopolitan port town (see Figure 2) in which multiple ethnic and religious communities coexisted and comingled (Vérin Reference Vérin1975). State-driven efforts to control and reconfigure Majunga's built environment can be traced back to the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. Sakalava royal leaders throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries traditionally prohibited the construction of homes in durable materials throughout the north-west region (Guillain Reference Guillain1845: 34–5).Footnote 10 After Queen Ravahiny repealed this prohibition in the late eighteenth century, Arab and South Asian traders were permitted by the Sakalava monarchy to build in stone, in similar styles and materials to those found in Zanzibar. Consequently, when nineteenth-century explorers and French military forces encountered the town, they observed a mélange of ethnic-political groups and corresponding housing styles.

Figure 2 Postcard of Majunga, c.1890–1900. Photographer unknown.

French colonial urban planners in Madagascar sought to control and constrain the everyday lives of colonial subjects through spatial design, in ways that resonated with colonial interventions elsewhere in Africa (Çelik Reference Çelik1997; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1988; Myers Reference Myers2003; Rabinow Reference Rabinow1989; Wright Reference Wright1991). Early French urban planners consolidated the sprawling lower residential and commercial settlement into linear arrangements of rues, parks and places (Grainge Reference Grainge1875). Following the 1895 conquest, French military officers worked from the lower town outwards, erecting large, imposing monumental buildings including a covered marketplace, prison, tribunal, governor's residence and town hall, and, later, infrastructural interventions such as roads, gutters and port improvements. They concretized the bifurcation between the lower and upper towns with a single main artery, the Avenue de France, which still runs from the sea to the current town hall. In so doing they incorporated the famous baobab tree, a precolonial landmark and important political and religious Sakalava symbol, into the colonial design (Deschamps Reference Deschamps1959; Feeley-Harnik Reference Feeley-Harnik1991). This road was soon extended to provide a critical conduit between the two separate areas: the envisioned European city of Majunga and the indigene village of Mahabibo, located about 2 kilometres east of the lower town.

Drawing on the urban-planning approach developed in Morocco and other French colonies, Colonel Hubert Lyautey and his colonial cadre in Madagascar conserved the fundamental layout of the cities they encountered (Rabinow Reference Rabinow1989: 228; Wright Reference Wright1991). Important to colonial interventions, however, were physical impressions of their presence created through the use of toponyms, memorials and monuments (Carter Reference Carter1988; Myers Reference Myers, Berg and Vuolteenaho2009; Bigon Reference Bigon2008). In Majunga, French planners named the streets after famous French colonial-era figures and sought to recast it according to a European design, while retaining what they perceived as the distinctive ‘Indo-Arab’ texture of the town (Catat Reference Catat1895). Gardens, promenades and ornamental spacesFootnote 11 took on great importance for French colonial planners as places in which they could cultivate aesthetic sensibilities, promote leisure lifestyles, and establish nationalistic and cultural ties to the metropole. Nineteenth-century arguments about the causal link between disease and environment, between menacing ‘miasma’ and urban pandemics, further added to the imperative of allocating gardens and open space in city planning (Green Reference Green1990: 74; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg, Vogel and Rosenberg1979). In the swampy, scorching hot town of Majunga, the need for expansive places where residents could theoretically enjoy the salubrious benefits of the sea breeze was unquestionable.

Place Mauriès was founded in 1902. It is striking that it was not mentioned in the city's Plan de Campagne for 1901 or 1903; rather, it was founded outside these master plans and prior to many massive infrastructural projects, including the provision of piped water, road building and the construction of marketplaces.Footnote 12 While it may have been the case that French military officers enjoyed the capability of bypassing the tedious bureaucratic urban-planning process that characterized the work of the Department des Travaux Publiques, it also suggests the profound symbolic significance of this envisioned Place Mauriès. The square was – and still is – situated in the middle of the ‘lower town’ (present-day Majunga Be), now largely inhabited by shopkeepers who came from South Asia during the mid-nineteenth century. Although they are locally referred to as ‘Karana’, this group comprises heterogeneous, multi-confessional communities of South Asian descent who reside throughout Madagascar. The use of the term ‘Karana’ is not without problems, as it both glosses over the complexity and diversity of the composite groups, but also carries a pejorative meaning. Drawing on the work of Sophie Blanchy (Reference Blanchy1995), I use this term throughout this article because it reflects local usage and designates ‘a reality, an originality and a specific identity’ (ibid.: 15–16). It should also be noted that many Karana are Malagasy citizens, but I contrast Karana with Malagasy groups throughout this article, following the practice of Karana groups who differentiate themselves from Malagasy.

In the early twentieth century, however, the lower town was historically ethnically mixed and composed of stone, thatch and wood houses. While Karana owned and occupied most of the stone houses in the lower town, some Europeans and assimilés leased work and residential space from them. Wood and thatch homes would have been more commonly occupied by Sakalava, Antalaotra, Makoa and newer Karana migrants, although these may have been cleared for the founding of the park. An earlier map from 1898 reveals plans to designate this square as a public marketplace, but by 1902 it was clearly demarcated and founded in memory of Captain Mauriès. As Place Mauriès was planted firmly in the centre of this heterogeneous neighbourhood, it stood as a key symbolic reference to French military memory and omnipotence.

Mauriès and the making of colonial roadways

Late nineteenth-century French military officers explicitly framed their project of colonial conquest as a kind of pioneering, of forging into unchartered and unclaimed territory. In Madagascar, as in other colonized territories, diverse Malagasy populations and other newcomers had long inhabited these lands. But it is the perception that is worthy of consideration; to be a pioneer suggests being the first. Among both the Malagasy and the French, being the first settler has historically implied a naturalized right to the land. Understanding themselves as pioneers, weary French colonial settlers gathered confidence and a sense of legitimacy in their troublesome work. Road building was perhaps the infrastructural activity that most aptly epitomized the colonial conquest in the eyes of French military officers. Roads served as a living artefact that testified to the primal presence, aspiration to omniscient powers and technological prowess of the French colonial force. Creating a road was one of the most obvious materializations of the figurative work of colonial domination over places and peoples.

By telling the story of Captain Mauriès, and why French military officers decided to commemorate his life and work in the form of a monument and a public square, we can unravel the haunting threads of colonial conquest and pacification in Madagascar. In 1897, following the military invasion of the island, Governor General Joseph-Simon Galliéni appointed Mauriès (see Figure 3), then Capitaine d'Artillerie de Marine, to manage the massive road construction project between the capital city of Tananarive and Majunga.

Figure 3 Capitaine Mauriès, c.1887–1901. Source: Conseil Général de La Réunion, Archives Départmentales.

Like many French soldiers, Mauriès hailed from a small, provincial town, Graulhet, located in the southern province of Tarn (De Gondi Reference De Gondi1903).Footnote 13 Mauriès had participated in the doomed Corps Expéditionnaire invasion in 1895, and witnessed the strategic errors committed in the navigation of an overland course to Tananarive. Drawing on his prior experience, Mauriès began an exploratory investigation to locate the ideal route for the road in March 1897.Footnote 14 Within four months, Mauriès had surveyed a viable preliminary route that corresponded to Galliéni's requirements for a plan that would allow for rapid construction, minimal expense, and avoidance of the most arduous passages of the existing Malagasy footpath (which had been used by the Corps Expéditionnaire).Footnote 15 In June 1897, construction began. Mauriès grew deeply frustrated in his efforts because of the minimal resources allocated to the project, which he blamed on the exhaustion of state funds that were meant for the construction of the route to the east.

Underpinning the entirety of the project was an utter reliance on scarce, forced Malagasy labourers.Footnote 16 Colonial archival records are littered with graphic references to the resistance, suffering and escape that characterized Malagasy experiences of forced labour.Footnote 17 In July 1900, Governor Galliéni wrote that, although he recognized Mauriès’ potential embarrassment over the floundering road project, it was impossible to recruit a single prestataire beyond those already provided.Footnote 18 All the labour pools were exhausted. District officers had become so desperate in their recruitment that they forcibly sent a disproportionate number of sickly, elderly and underage men, to the detriment of the ‘sanitation’ situation at the site.Footnote 19 A large number of these labourers died or became ill from their work on the road.Footnote 20 Tales of the harsh and tiring labour conditions circulated around highland villages. Upon the approach of Malagasy enlisting agents, Malagasy villagers fled their communities.Footnote 21 These abuses would persist on other construction sites for public works across the island throughout colonial times (Fremigacci Reference Fremigacci1986; Sharp Reference Sharp2003; Sodikoff Reference Sodikoff2005). Towards the end of 1900, Mauriès’ campaign was supplied with some 4,000 workers, which allowed for the long-anticipated completion of the road. French colonial officers finally celebrated the opening of the 342-kilometre road in December 1900.Footnote 22

In a paradoxical twist, Mauriès lost his life to the road. Finding himself physically depleted from his work on the road campaign, he died of ‘exhaustion’ eleven days after completing his final report to Governor Galliéni on 29 April 1901 (Guide Annuaire 1902). His body was temporarily buried in Tananarive; in July 1902, his remains were exhumed and repatriated to his home village of Graulhet (Anonymous 1902).

Monumentalizing the pioneer and masking affliction

French military officers unveiled the Place Mauriès in 1902 to celebrate Mauriès’ ‘pioneering’ work in the colonial conquest and to proclaim French domination over the land (De Beauprez Reference Beauprez1902). In a clearing equivalent to a small city block, they carved out a public square marked by paths that crossed in the form of an ‘X’, and erected a towering stone obelisk, approximately 6 metres high, on the far south-eastern side (see Figure 4). Eventually, large iron cannons were sited in a circle around the obelisk, amplifying the performance of French military potency. Designed by French architect Paul Fouchard, the obelisk was adorned with a large bronze medallion crafted by Henri Coutheillas, a renowned sculptor (see Figure 5). Coutheillas sculpted a relief, portraying a deeply pensive and ‘invincibly energetic’ Captain Mauriès, donning his military medals and surrounded by laurels (De Gondi Reference De Gondi1903). Early photographs of the square show a dusty place, barren of people and trees, and dwarfed by the disproportionately tall obelisk (see Figure 6). Later photographs reveal the addition of street lamps, trees and a simple wooden fence enclosure.

Figure 4 Place Mauriès, c.1903. Source: Centre des Archives d'Outre Mer, Aix-en-Provence, France, FR ANOM 44PA134/24.

Figure 5 Bronze medallion of Capitaine Mauriès, placed on original stele. Source: Armée et Marine, 1903, vol. 204, p. 5.

Figure 6 Postcard of Majunga, c.1910. Photographer unknown.

French military officers and colonial settlers who helped usher the Place Mauriès into existence were likely informed by the iconography of public squares in the metropole, especially in the small, provincial towns from which many French soldiers hailed. In nineteenth-century French towns, public squares were mutable, flexible kinds of places. They were sites of boisterous wedding processions; festivals and dancing; lively markets that brought together villagers from dispersed hamlets; and darker forms of governance including public punishment and execution (Weber Reference Weber1976: 10–11, 379, 392).Footnote 23 Monumental statues in the public spaces of provincial France were symbolic devices harnessed to emblematize liberal values, build local patriotism, and envision the imagined community of Frenchmen united beyond royalist and republication factions (Agulhon Reference Agulhon and Lloyd1981; Anderson Reference Anderson1991; Cohen Reference Cohen1989: 491; Weber Reference Weber1976: 388, 437).

Influenced by these historical conceptualizations of public squares and monuments, colonial authorities aspired to create a lasting memorial to Mauriès through their choices of stone and metal. Indeed, for some time this space was an important site for the performance of military power and French domination. In the 1900s and early 1910s, military troops held a fortnightly music concert at Place Mauriès on Sunday evenings, as well as at the military hospital and public garden.Footnote 24 The image of the square figured prominently on postcards and in military bulletins, emerging communication technologies by which French imperial power was represented to and consolidated among publics in the metropole and beyond (see Figure 7). However, by 1912, the Place Mauriès’ popularity began to diminish. City administrators halted the concerts in the square because of low attendance. Mayor Carron reported that Place Mauriès was generally less frequented by the Majungaise population because of the ‘rampant mosquitos’ and ‘lack of ambiance’.Footnote 25 European and assimilé residents generally preferred the Bord de la Mer, where the breeze blew and the mood was lively.

Figure 7 Postcard of Majunga, c.1920s. Photographer unknown.

But not everyone agreed. One year later a public petition of European residents demanded the resumption of the military music concerts every Thursday evening, from 8.30 to 9 p.m.Footnote 26 The city council ruled to allow occasional concerts at Place Mauriès, but noted that regular concerts would take place at the Bord de la Mer and the military hospital. The city allocated modest sums to maintain and embellish the square throughout the 1920s, including the construction of an improved fence in 1927.Footnote 27 By 1945, the significance of the garden had seriously declined. The financially strapped city council deliberated whether to auction part of the grounds to generate income to buy a new hearse. In a desperate attempt to resolve an ever-increasing deficit, the council sold a section of the garden, leaving a more modest public square intact.Footnote 28 Although the garden was a site of childhood play for nearby residents, few public events seem to have been held there after 1940.Footnote 29 By the 1950s, many locals reported, the garden was neglected and had decayed into a veritable wasteland. Within the span of forty years, the Place Mauriès became a peripheral site paradoxically set within the centre of the burgeoning city.

Detritus and deletions: imaginings of post-independence Mahajanga

Little about the Place Mauriès after 1945 remains in the archival record. Sometime in the post-independence period, most likely during the 1970s, Place Mauriès was renamed the Jardin Ralaimongo.Footnote 30

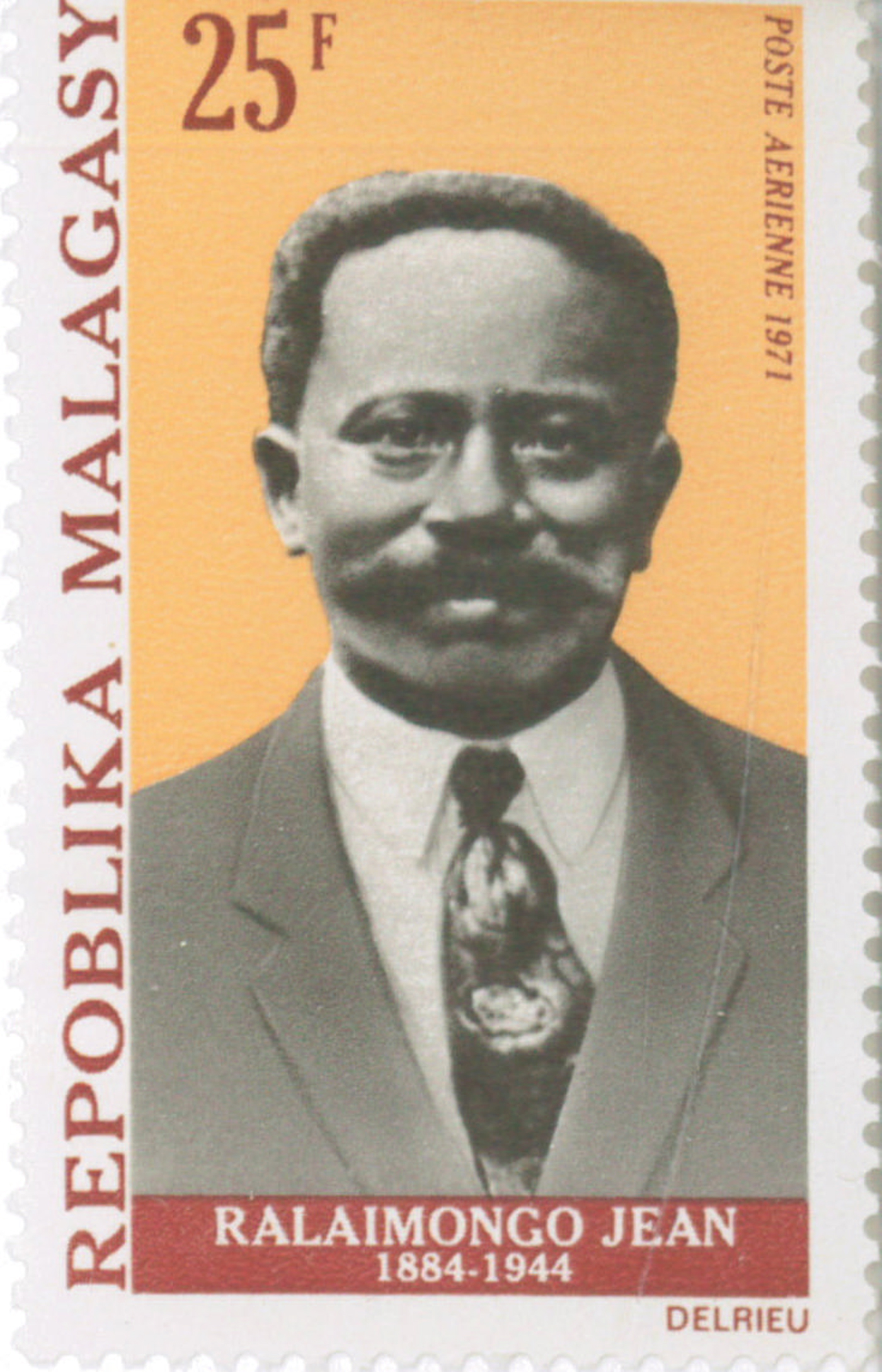

Jean Ralaimongo (see Figure 8) was a key nationalist leader in the early anti-colonial struggle. Born in 1884 in highland Madagascar, Ralaimongo was enslaved at an early age. His master later adopted him and he was liberated after the French colonization of Madagascar at the age of fourteen (Domenichini Reference Domenichini1969). He pursued teacher training in Malagasy Protestant missionary schools, and over time he became conscious of the contradictions between French republican principles and the disparate political and economic rights between Malagasy and French. Ralaimongo's political commitments were further solidified through two more years in France, where he collaborated on political publications with other progressive colonial intellectuals, such as Ho Chi Minh and Louis Hunkanrin (Edwards Reference Edwards2003: 15; El Yazami Reference El Yazami, Hargreaves and McKinney1997: 116; Spacensky Reference Spacensky1970: 28). After his final return to Madagascar, he undertook a spirited campaign during the 1920s and 1930s, advocating equal political and civil status between Malagasy and French, as well as labour regulation reform (Gow Reference Gow and Crowder1984: 674). He and his compatriots drew on French republican discourses of equality and justice to promote their claims in opposition to the colonial regime, only later abandoning the goal of assimilation and striving towards national independence. He died in 1942, following years of exile in the north-western town of Port Bergé, long before the independence of Madagascar was realized in 1960.

Figure 8 Image of Jean Ralaimongo on a Malagasy stamp, 1971.

At first glance, the decision to rename the garden in Ralaimongo's memory resonates with the efforts taken in many post-independence African nation states to honour anti-colonial figures. Post-independence African regimes have sought to capitalize on the lasting political efficacy of erecting new memorials commemorating precolonial leaders, nationalist heroes and allegorical figures. But, as scholars have shown, these honorary monuments often efface the regional, political and ethnic differences that threaten to rupture the notion of a homogeneous, unified nation state (Arnoldi Reference Arnoldi2003; Reference Arnoldi2007; Becker Reference Becker2011; Chirambo Reference Chirambo2010). In Madagascar, state-sponsored actors have also transformed certain anti-colonial activists and events into national heroes, positioned to stand as icons of national identity (Tronchon Reference Tronchon1986).Footnote 31 Performative efforts at building an imagined cohesive nation state through the elevation of key figures have revealed their ambiguity as symbolic figures (Galibert Reference Galibert2006). The commemorative monument to the 1947 anti-colonial rebellion that sits prominently in Tulear, enjoining the viewer to ‘remember the struggle of the Malagasy on 29 March 1947’, for example, layers a national imaginary onto a region that was not linked to – or at least relatively uninvolved in – this historical event (ibid.).Footnote 32 Commemorative monuments thus reveal the instability, ambiguity and patchiness of national identity and memory.

In this vein, the incongruous commemoration of the rural-cum-urban intellectual Ralaimongo in Mahajanga is particularly striking. Ralaimongo's nationalist campaign was not far-reaching across the island, and thus exposed the long-standing disjunctures between the highlands and the coast. In an ill-fated strategy to expand his anti-colonial movement into the north-west region, Ralaimongo aligned himself with the mother of the Sakalava queen Soazara, both of whom resided in Analalava, north of Majunga. He sought and secured her written permission to bring Soazara to Port Bergé and to involve her in his nationalistic campaign in September 1936. But this misstep was interpreted as an attempted kidnapping and invoked the rage of royal Sakalava dignitaries (the true authorities of Soazara), costing Ralaimongo dearly in terms of regional support (Ballarin Reference Ballarin2000: 288–98; Feeley-Harnik Reference Feeley-Harnik1984: 15; Randrianja Reference Randrianja2001: 300).Footnote 33 In Mahajanga, Ralaimongo's outreach efforts were met with disdain by Sakalava dignitaries who regarded him as an outsider and rejected his ‘foolish’ anti-French campaign (Ballarin Reference Ballarin2000: 291; Randrianja Reference Randrianja2001: 301).Footnote 34 Ralaimongo's story resonates with the contingent ways in which anti-colonial movements unfolded elsewhere (Cooper Reference Cooper2014).

The casting of Ralaimongo as an outsider in the 1930s, followed by the (re)composition of the city's ethnic fabric in the decades that followed, rendered his symbolic positioning at the heart of old Majunga even more paradoxical. As the city of Majunga grew during the 1930s and 1940s, it became increasingly heterogeneous, populated by Sakalava, Tsimihety, Merina, Betsirebaka (migrants from south-east Madagascar), Makoa (descendants of East Africans) and Comorians, not to mention Karana and Europeans. By the 1950s, the city was resolutely dominated by Comorians and Comorian-Malagasy descendants. While the Jardin Ralaimongo sat in predominantly Karana Majunga Be, the rest of the city's landscape was shaped by the vernacular building initiatives of Comorians, Comorian-Malagasy métis (zanatany) and other Malagasy migrants. Comorians occupied subaltern administrative posts, including in the police and commune, as well as manual labour positions as dockers, small-scale shopkeepers and domestic workers (Radifison Reference Radifison and Allibert2007: 137).

Although the population of Majunga was at least 50 per cent Comorian, the Merina population – which was estimated at around 20 per cent in 1959 – exercised a considerable economic and political influence over the town's inhabitants (Deschamps Reference Deschamps1959: 90, 188–9).Footnote 35 One scholar noted that, while many mid-ranking administrative officials were ‘côtiers’, the majority of high-ranking administrators in the city were identified ethnically as Merina (Vérin Reference Vérin1990: 184, quoted in Radifison Reference Radifison and Allibert2007: 133). The complaint that Merina still occupy these valuable posts and disproportionately dominate the administrative life of Majunga is a common refrain today, reflecting the socio-cultural, political and economic advantages acquired by Merina groups during monarchical times and accentuated during French colonization (Radifison Reference Radifison and Allibert2007: 132–5). And while it is impossible to claim this with certainty, the decision to rename the Place Mauriès as the Jardin Ralaimongo in the 1970s or 1980s likely served the interests of a city administration dominated by highland migrants. How, why and exactly when the decision was made to rename the park remains unknown. The elevation of Ralaimongo as a national independence hero, however, smoothed over the troubling, long-standing fissures between highlanders and côtiers, between urban elites and rural peasants, and between enduring political factions, to establish an imaginary, integrated political corpus.

It is notable that minimal effort was taken to inscribe Ralaimongo's memory on the park. The name change to the Jardin Ralaimongo was marked by a simple placard on the outside fence of the garden. Between the 1960s and 1980s, however, considerable effort went into dismantling and effacing the physical remnants of Mauriès on the obelisk. The ornate bronze medallion depicting Mauriès’ face was removed and confiscated, although the identity of those involved and the whereabouts of the medallion today remain unknown. The engraving of Mauriès’ name and title were rubbed out on the obelisk's stone surface. The giant heavy chain that had tethered the cannons to each other was removed. The renaming and razing of colonial-era monuments and memorials like these have been common strategies to de-memorialize the colonial past throughout post-independence Africa (Autry Reference Autry2012; Coombes Reference Coombes2003; Deacon Reference Deacon, Nuttall and Coetzee1998; de Jorio Reference de Jorio2006). And, as Çelik describes in relation to Place des Martyres in Algiers, these changes to transform Place Mauriès into the Jardin Ralaimongo effectively superimposed a new symbolic order on an existing space, without reworking the site's fundamental spatial character (Reference Çelik1999: 66, 69).

What is notable, however, is that this particular garden was uniquely chosen as a place of post-independence transformation. Neither of Mahajanga's other two gardens – the Jardin Cayla, named after the former colonial Governor General, and the Jardin Damour, named after the city's principal architect in the 1930s – have been renamed. All of the street signage in the immediate vicinity – and, in fact, in most of the town – reverberates with the echoes of French colonial-era figures such as Galliéni, Marechal Joffre, Flacourt, Jules Ferry and Pasteur. The overall layout of the town, with its wide boulevards and prominent colonial-era administrative buildings, harks back to the colonial past.Footnote 36 The reasons why this garden represented a site worthy of painstaking alterations, name-changing and symbolic metamorphosis are unclear: perhaps the conspicuous monument too boldly recalled French colonial domination; perhaps it was part of a larger project of renaming that was left undone; or perhaps it seemed critical to stake independent Malagasy national identity here because the garden sits in the middle of the Karana merchant community, a community that most Malagasy have historically understood as dominant outsiders.

In order to elucidate these layerings of historical (re)presentation of the Jardin Ralaimongo, one might ask the following question: how have post-independence Malagasy regimes more broadly sought to negotiate the country's ties to the colonial past? Lesley Sharp has described how the post-independence Madagascan state has historically cast itself in the form of ‘Franco-Malagasy hybridization’, drawing on both ‘indigenous notions of power and French republicanism’ in its public rhetoric, symbolism and performance (Sharp Reference Sharp2002: 54). This is evident in the customary framing of postcolonial chronological periods as successive republics (Tronchon Reference Tronchon and Jacob1990),Footnote 37 as well as in the post-independence state slogan that reverberates with French republican ideals: ‘Tanindrazana – Fahafahana – Fandrosoana’ (‘Ancestral Land – Liberty – Progress’) (Sharp Reference Sharp2002: 55).Footnote 38

The First Republic, under President Philibert Tsiranana (1960–72), is widely understood to be an extension of the French colonial administration. Significant shifts in the post-independence Malagasy state took place under President Didier Ratsiraka (1975–93, 1997–2002), who instituted a radical socialist regime and fashioned a national Malagasy language that removed dialectical differences. It was also during the 1970s that the post-independence Malagasy state appears to have made the most visible alterations to the material legacy of the colonial regime. City place names were modified away from French iterations to conform to perceived precolonial phonetic pronunciation: for example, Tananarive became Antananarivo, and Majunga became Mahajanga. And, in 1972, the ever-present image of former Governor General Joseph Galliéni on the colonial monetary currency, the Madagascar-Comores CFA franc, was replaced by depictions of local flora and fauna and classic, romanticized Malagasy ethnic portraiture on the newly minted Malagasy franc (renamed again in 2005 as the Malagasy ariary).Footnote 39 History textbooks and curricula were thoroughly revised to centralize the island's position in the regional and global historical landscape.Footnote 40

Anthropologists have documented in detail how, at various times, these post-independence enunciations of Malagasy nationhood and the colonial past have been taken up, silenced and recrafted into localized, meaningful forms of historical consciousness. Jennifer Cole demonstrated how town dwellers in eastern Madagascar reworked colonial symbols and systems of rule associated with the built landscape into local constructions of community, such as the road that contained memories of French forced labour and also of ancestral protection and blessings (Cole Reference Cole1998: 620).Footnote 41 In her study of historical consciousness among youth in Ambanja, Sharp shows how students narrated their position within Malagasy political history through local experiences of youth resistance and protest, rather than the meta-narrative moments set down in textbooks (such as the 1947 revolution). For young people in north-west Madagascar – and many côtier dwellers in Mahajanga – ideological constructions of a unified Malagasy nation were always ambiguous, since their ties to tanindrazana (homeland) were in fact ‘enforced through language, burial practice and fomba [custom]’, all of which are intensely localized (Sharp Reference Sharp2002: 71).

So what are we to make of these contrasting hybridized and fragmented compositions of nationhood in post-independence Madagascar, and their relevance for the historicity of the Jardin Ralaimongo? In some ways, the Jardin Ralaimongo can be understood as a palimpsest site that effectively performs a hybridized Franco-Malagasy history, through the retention of some physical remnants of the colonial era. While the text and imagery associated with Mauriès on the overbearing obelisk were erased in the 1970s, neither the obelisk itself nor the cannons that surround it were removed. Instead, these artefacts were juxtaposed with a hastily placed sign honouring Ralaimongo, at a moment when the socialist regime needed to conjure up a unified Malagasy state. Imaginings of a cohesive postcolonial Malagasy island nation have been fraught, continually refracted through more intimate and exigent ties to locality, regionalism and ancestral lands. Yet, in the case of the Jardin Ralaimongo, the material traces of Mauriès and the colonial past were not subsumed into local constructions of belonging, but rather they were left to decay. It was only following the initiative of a different, specific group of city dwellers that the space was once again appropriated and imbued with new meaning.

Blood and sap: tethering together land and aspirations for belonging

Located in the heart of the Karana majority neighbourhood Majunga Be, the park is woven into the childhood memories of many older residents. Older Karana inhabitants described how the garden began to deteriorate through neglect, declining into an uncultivated tangle of neck-high weeds throughout the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote 42 With the increasing absence of communal waste disposal services, people began to toss their rubbish into the park, and to use the space as a public toilet. Dismayed Karana residents described this decay as a descent into a kind of ‘bidonville’, referring to the vast shantytowns in the metropole. Karana, who largely occupy the city's wealthier strata, narrated how the garden was gradually invaded by careless – presumably lower-class – Malagasy who did not hold the same values as they did with regard to preserving the space.Footnote 43 From that point onwards, the park largely remained an eyesore and a desolate wilderness within the city until the 2000s. Karana inhabitants’ nostalgia for the more Eden-like time of the Jardin Ralaimongo, as well as of the city more generally, reflects both a critique of the present political situation and a sorrowful loss of an imagined time when socio-spatial boundaries were more heavily policed.

Even if some Karana residents recall the past with longing, almost all Karana living in Mahajanga have long struggled with the tensions of belonging in Madagascar. South Asian migration from the Kathiawar peninsula and the Gujarat province to Madagascar resulted from the centuries-long Indian Ocean trade. From the mid-nineteenth century, South Asian petty merchants and traders settled more permanently in Majunga, and they established strong commercial enterprises and networks in Majunga from the early twentieth century. When Europeans left Majunga during the economic crisis of the 1930s, Karana became the primary owners of real estate and assets in the city (Blanchy Reference Blanchy1995: 169). Throughout the 1940s, Karana families expanded beyond the export–import trade into the industrial production of oil, soap and natural fibres and opened some of the largest factories in the city's history (ibid.: 170). By 1950, it was estimated that Karana owned some 80 per cent of real estate in Majunga (Bardonnet Reference Bardonnet1964: 158, quoted in Blanchy Reference Blanchy, Pal and Chakrabarti2006: 101), and in contemporary times Karana have come to be generally regarded as indispensable to the functioning of the Malagasy economy (Blanchy Reference Blanchy, Pal and Chakrabarti2006: 102). If Karana hold economic hegemony within the town, this is exemplified by the spatial dominance of their towering shophouses that line the perimeter of the square in which the Jardin Ralaimongo sits.

While Karana have firmly established their economic presence in the city's everyday life, their juridical citizenship status has been more precarious. During colonial times, Karana were perceived suspiciously by the French authorities, who resented and mistrusted their position as economic competitors (Fremigacci Reference Fremigacci1983: 426–32). Their status as Muslims and (often) British subjectsFootnote 44 contributed to their ambiguous positioning vis-à-vis the French colonial government. Legislation passed in 1928 allowed French naturalization for some foreigners, but by 1958 fewer than 5,000 non-Malagasy had secured citizenship (Blanchy Reference Blanchy1995: 261).Footnote 45 Following Madagascar's independence in 1960, citizenship was granted on a jus sanguinis basis, through descent rather than place of birth. Furthermore, the sale of land to foreigners has long been prohibited in Madagascar. Although many Karana have found ways to obtain citizenship or access land through kinship connections with naturalized Karana in Madagascar, there still remain an estimated 5,000 Karana without citizenship (Blanchy Reference Blanchy2008: 5). In short, the citizenship status of many Karana is tenuous and contributes to an insecure sense of belonging to their natal land.Footnote 46

While most Karana share a linguistic field with the Malagasy population, they strictly demarcate their everyday life – through their dress, by speaking South Asian languages among themselves, and in their schooling, marriage practices and lifecycle rituals. It should be reiterated here that ‘Karana’ are in fact a highly heterogeneous composite of diverse groups of South Asian origin. Among the Karana population of 20,000 in Madagascar are three groups of Shiite Muslims, one group of Sunni Muslims, and a small contingent of Hindus (sometimes referred to as Banians). The profound socio-religious differences among these groups have precluded any lasting attempts at unification. Despite these rifts, most Karana have historically and collectively understood themselves as a minority group working to preserve their lifestyle, religions and cultural practices in an inhospitable social milieu.Footnote 47 Indeed, most Malagasy perceive Karana as elitist and snobbish (miavona), as evidenced by their social distance and general disinclination to intermarry with Malagasy, and as dishonest and cruel, regularly cheating Malagasy customers and demeaning Malagasy workers (manao andevo or manandevo: literally, to enslave someone, or to treat them like a slave). A common stereotype and critique of Karana within the capitalist economy is that they are greedy and value their wealth over interpersonal relationships (mpangoron-karena: literally, a person who gathers or seizes wealth) (see Celton Reference Celton and Allibert2007: 251).

A series of popular uprisings in which Karana have been the targets have validated Karana perceptions of their vulnerability in a hostile social environment in Madagascar. Popular unrest and a military coup in 1972 marked an abrupt break from an earlier post-independence era of Malagasy political and economic history (Randrianja and Ellis Reference Randrianja and Ellis2009: 187–99). Private industries and real estate were gradually nationalized in the 1970s. As significant landholders and commercial agents across the island, the French, and especially Karana, feared the repercussions of Ratsiraka's socialist programme and increasingly found themselves the targets of rising and vociferous xenophobic sentiments. By the late 1970s, pillaging of Karana-owned shops and official pronouncements against the presence of Karana had spread across the island nation. But in Mahajanga, xenophobic sentiments tended to be targeted at those of Comorian descent; these feelings escalated into a brief but violent two-day conflict in 1976–77 in which at least 1,500 Comorians died and 16,000 fled.Footnote 48 Still, Karana were also vulnerable during this event and over the following decades, as the economic situation wavered and collapsed. In 1987, 1991 and again in 1994, they faced direct attacks on their shops and property in the island's major cities, including Mahajanga.Footnote 49 Karana defended their position by asserting: ‘We are zanatany, but we are not the tompontany!’Footnote 50

It was in this vein that Karana residents emphatically described to me their deep love of Madagascar as their natal land, and justified their own sense of belonging here through their generations-long presence in Mahajanga. And it was to demonstrate their allegiance to the city and to honour their revered religious leader that one Karana group – the Muslim Dawoodi Bohra congregation – initiated a restoration of the neglected garden in the 1990s. The Mahajanga Dawoodi Bohra congregation is part of a larger worldwide community of 1 million people, most of whom reside in India, with some living along the East African coast (Blank Reference Blank2001). They have been described as a ‘minority within a minority’, partly by virtue of their esoteric beliefs, and have protected themselves from repeated persecution by other Muslims through isolation (Blank Reference Blank2001: 274; Blanchy Reference Blanchy1995: 200). Their former spiritual leader, His Holiness Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin, was believed to be directly in contact with a lineage of hidden imams who have remained concealed since the twelfth century (Blank Reference Blank2001). He served as a guide not only on religious matters, but also more generally on marriage, business, health and well-being, and humanitarian practices (Blanchy Reference Blanchy1995: 200). According to local adherents, the Holy Leader himself visited Mahajanga three times over the years (see Figure 9), and on his last visit he encouraged the community to undertake the revitalization of the garden as a social improvement project.

Figure 9 His Holiness Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin, Mahajanga (Majunga), 1963. Source: <http://www.majungajamaat.blogspot.com>, accessed 2 September 2013.

Inspired by the Holy Leader, Mr Tourabaly, a Bohra congregant and local resident, led the congregation in renovating the garden. Beginning in 1995, the Bohra congregation cleared the weeds, traced out paths, and planted trees and bushes using clippings that had been brought by residents (see Figure 10). Although the congregation initially provided financial support, most of the upkeep is now financed through the sale of advertising placards on the outside of the garden's fencing. In 2003, the mayor of Antananarivo came to inaugurate the park, showing support for the work of the Bohra congregation. Mr Tourabaly has taken much pride in his work on the garden, but has done so in this ever-oscillating socio-political landscape of exclusion and inclusion. Indeed, the congregation's appropriation of the park can be understood as a reflection of their intention to durably inscribe on the urban landscape their identity as citizens of the city. When Tourabaly asked the commune to give his own or his congregation's name to the park, however, they rebuffed him: ‘But you're an outsider [étranger] here!’ Tourabaly justified his belonging to the city with reference to his labour in the park: ‘If I were really a foreigner … I wouldn't be cleaning and caring for this garden!’Footnote 51

Figure 10 Jardin Ralaimongo, with the stripped obelisk in the background, August 2013. Photograph: David Epstein.

On a balmy evening in 2013, he and I walked through the garden and he pointed out the acacia, neem and bougainvillea trees. He explained how he was deeply inspired by the Holy Leader's horticultural metaphor that trees are living things, with deep connections to human beings, as evidenced by their blood-like sap, and therefore they require care and respect. Tourabaly likened his own efforts to restore the garden to a kind of meditation. ‘Cleaning is like praying,’ he said. These imagined connections between people and plants, between the body of the person and the health of the land, cut across many different cultural and temporal contexts. And it was perhaps these imagined connections between people and plants, bodies and place, and between a diasporic population and its revered leader, that gave the restoration project salience and meaning. By erecting a placard to honour their beloved leader, Bohra residents superimposed their history and sense of belonging onto the local urban landscape and strengthened their transnational ties to their religious community. At the same time as they memorialized their celebrated imam and the legitimacy of their own belonging to the city, they actively forgot – or perhaps silenced – the colonial history tied to Mauriès and the anti-colonial history of Ralaimongo, both previously inscribed on the park. Here, as scholars have shown elsewhere, remembering and forgetting were coeval processes undertaken by particular actors advancing their aspirations and recollections, in relation to the broader socio-historical processes of the times.

The more vexing issue at stake is who exactly is doing the forgetting here? If we understand forgetting to be not only the silencing of some parts of the past, but also as being characterized by inaction, then who precisely is neglecting the park? Karana, as well as many Malagasy residents, attribute blame to Mahajanga's city administration, which is widely regarded to be unethical, corrupt and irresponsible in all matters concerning the care of the town. City officials themselves confirm that the commune has historically had little involvement or interest in the garden, aside from budgeting for the gardener's salary. They maintain that the city prioritizes much more urgent matters of sanitation and basic infrastructural support.Footnote 52 City dwellers who consider themselves zanatany (autochthones), or true côtiers, perceive city administrators as homogeneously composed of privileged, educated, elite Merina outsiders, who manage to secure desirable bureaucratic positions through access to kinship and to professional and ethnic networks. A closer look suggests that the commune administration is perhaps more heterogeneous, yet several zanatany city workers alluded to the ethnically demarcated labour hierarchies in which they felt marginalized in lower-ranking roles in the commune.

While the city administration is an obvious actor in neglecting the park, we may also wonder why Malagasy city residents, beyond the Bohra community, have ignored it. The Jardin Ralaimongo remains a kind of deserted and underutilized space. At any given time, one finds a handful of passers-by, suggesting that the place does not hold much popularity or significance for most of the residents of Mahajanga. Many people with whom I spoke suggested that gardens are simply frivolous and insignificant in the current political and economic crisis, where most Malagasy struggle daily to secure basic food and shelter. Others suggested that the act of passing time in a park is a vazaha Footnote 53 custom that Malagasy find unappealing and perplexing. Yet, it is remarkable that Mahajangaise residents take extraordinary efforts to occupy, display themselves and socialize in other public spaces in the city. Take the famous boardwalk (Bord de la Mer), where young and old take evening strolls and eat brochettes; the environs of mosques, where men cluster and debate politics; and the Sakalava royal compound (doany), which is vibrantly occupied, especially during the annual fanompoa-be. And if we accept that the most frequented, crowded places are those that hold socio-economic and symbolic significance, then it is clear that these are the places that matter to today's city dwellers.

I suggest that the precise location of the Jardin Ralaimongo in the heart of Majunga Be – a neighbourhood dominated by the imposing, if crumbling, colonial-era shops and residences of Karana residents (see Figure 11) – renders it a marginal place in the everyday life of the Mahajangaise. Residual tensions between Malagasy and Karana communities have perhaps been historically mediated through the occupancy of separate places for leisure and residence in the city, yet Malagasy experience this segregation as inhospitable and discriminatory exclusion. As one thirty-something zanatany man described to me:

You see, people in Mahajanga, they like ambiance! They like to sit on the steps in front of the mosque, cathedral or post office, to talk, socialize, take in the street scene. But we wouldn't dare do that in front of a Karana shop, because they'll tell us to leave. They don't like us to be near their spaces … but if you're vazaha or Karana, then they don't mind.Footnote 54

Figure 11 Majunga Be, 2014. Photograph: David Epstein.

Just as Malagasy residents avoid occupying Karana storefronts in other parts of the city, so too is the neighbourhood of Majunga Be perceived to be a Karana-dominated space in which many Malagasy can never be fully at ease or embraced. In the reclaiming of the Jardin Ralaimongo by Bohra congregants, Karana residents have signalled their ownership of some public space in the city. They have further entrenched their dominating presence in the city's landscape, while Malagasy residents have sought out and made salient other public spaces.

Conclusion

The history of the Jardin Ralaimongo, in all its reincarnations, reveals the interconnectedness and active processes involved in remembering and forgetting. It is emblematic of how inhabitants across diverse cultural and geographical contexts in Madagascar have established territorial claims by invoking ancestors and linking them through ritual to material residues, usually tombs. Whereas in other parts of Madagascar social organization is effectively tied together through tombs (Graeber Reference Graeber1995: 262), it could be argued that the communities discussed above (French, Malagasy, Karana) have been constituted through the (re)appropriation of this garden. These ritual practices are acts of care. They are the means through which authority is expanded and territoriality is grafted onto spatial landscapes.

But the case of the Jardin Ralaimongo illustrates that such mnemonic practices are not bound to tombs, or to ritual practice, but have been enacted in and extended to everyday, urban spaces. By raising a monumental stone and bronze obelisk in a centrally located square, French military officers created a concretized topographical lieu de memoire that would have maximum public exposure and would physically endure the passage of time (Nora Reference Nora1989). This site of memory was designed to stir a romantic nostalgia for the colonial triumph of clearing, claiming and curating new territories. At the same time, the difficult pasts that threatened this mythical rendering – what Saul Friedländer calls Heimatgeschichte (as described in La Capra Reference La Capra1998: 26; see also Friedländer Reference Friedländer1993) – were elided: namely the histories of violence, suffering and fearsome tyrannies over toiling Malagasy bodies, and the inescapable mortal vulnerabilities that bound together colonizers and colonized. With the memorialization of Ralaimongo, the memory of Mauriès was suppressed and literally erased from the topographical landscape, to make room for the celebration of a mythical nationalist activist serving to unify a distressed island nation. And the memorialization of the living leader His Holiness Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin involved a submersion of these earlier histories, allowing the Dawoodi Bohra community to proclaim their enduring ties to Mahajanga.

The Jardin's biography also illustrates the profound meaning of neglect and decay, and the way in which these processes have been transformative and have worked to diminish the power of places and political figures. In order to memorialize one revered figure, the earlier material markers of historical personages – whether Mauriès’ plaque or Ralaimongo's sign – had to be actively concealed through defacement and disuse. The symbolic space of this garden, it seems, could not hold the living memories of Mauriès, Ralaimongo and His Holiness Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin in the same place and time. Or perhaps memorializing all of these figures together would expose all the fractures that threaten to cleave the tenuous socio-political and ethnic relationships of the very different groups that comprise Mahajanga. While Andreas Huyssen suggests that public monuments ‘stand simply as figures of forgetting, their meaning and original purpose eroded by the passage of time’ (Reference Huyssen1993: 249), I suggest that something quite different has been taking place in the case of the Jardin Ralaimongo. Forgetting here has partly transpired passively over time, but it has also – and perhaps more importantly – been actively enacted through material processes of effacement and desertion. Like empty émigré houses in highland Madagascar, decay is ‘meaningful’ as a purposeful negotiation of tenuous social relationships (Freeman Reference Freeman2013: 95).

Calls to construct and imagine a unified citizenry – be it the French Malagasy colony, the post-independence Malagasy nation state, or even the Bohra community – through consecutive reworkings of the city's landscape have been inherently rife with ambiguities. The case of the Jardin Ralaimongo suggests that the historical refashioning of the city's built environment has necessarily entailed erection and elevation, intertwined with burial, erasure and abandonment. In an effort to disentangle the detritus of previous pasts from the living memory of the city, competing groups have aspired to re-envision futures of communal cohesion – and exclusion. The history of the Jardin Ralaimongo draws our attention to the ways in which ideological notions of colonial or postcolonial nationhood have been superseded by ties to specificities of local places. It also illustrates how active and passive recollection and forgetting are constituted through the remaking of intimate, local places. It is perhaps precisely through these repetitive acts of forgetting and abandonment that the residents of Mahajanga have laboriously sustained their tense and indeterminate coexistence over time.

Acknowledgements

Research for the larger project of which this article is part was conducted in Madagascar and France between 2011 and 2014. The research was supported by a Fulbright-Hays fellowship and the Doctoral Program in Anthropology and History and the African Studies Program, both at the University of Michigan. I would like to express my gratitude to Gillian Feeley-Harnik, Derek Peterson, Gabrielle Hecht, Will Glover and Pier Larson; the participants in the Anthropology and History workshop at University of Michigan; and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and generative insights on earlier drafts. I am deeply indebted to the inhabitants of Mahajanga for sharing their time, memories and perspectives of the city's history with me. In particular, I would like to thank M. Hadj Soudjay Bachir Adehame and M. Tourabaly for generously extending their knowledge of Parc Ralaimongo, but also their personal archival and photographic collections. Finally, I am most grateful for the research collaboration and helpful insights of M. Ben Houssen, Mme Battouli Benti and M. Ben-Taoaby.