The critical period hypothesis proposes that the early phase of psychosis, including any period of initially untreated psychosis, is a ‘critical period’ during which symptomatic and psychosocial deterioration progresses rapidly. Afterwards, progression of morbidity slows or stops, and the level of disability sustained, or recovery attained, by the end of the critical period endures into the long term. Reference Birchwood, Todd and Jackson1

The critical period hypothesis has underpinned the development of services specialising in early intervention in psychosis in the UK and elsewhere, Reference Craig, Garety, Power, Rahaman, Colbert and Fornells-Ambrojo2–Reference Petersen, Nordentoft, Jeppesen, Øhlenschaeger, Thorup and Christensen4 but some have argued that services dedicated to early intervention ‘for an arbitrary “critical period” of a few years’ waste scarce resources. Reference Pelosi and Birchwood5 Moreover, the critical period is still a hypothesis, with two testable central premises. The first is that outcomes stabilise beyond the critical period and a few longitudinal studies have reported stability ensuing 2–5 years after the onset of psychosis. Reference Carpenter and Strauss6,Reference Eaton, Thara, Federman, Melton and Liang7 The second is that untreated initial psychosis is associated with increasing debilities in the medium to long term, and researchers differ on this issue as to whether outcome was measured in the first year, Reference Browne, Clarke, Gervin, Waddington, Larkin and O'Callaghan8,Reference Ho, Andreasen, Flaum, Nopoulos and Miller9 after 2 years Reference Addington, van Mastrigt and Addington10–Reference Malla, Norman, Schmitz, Manchanda, Béchard-Evans and Takhar13 or up to 15 years after presentation. Reference Bottlender, Sato, Jäger, Wegener, Wittmann and Strauss14,Reference Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff and Giel15 No single study has tested both central premises.

In this study we assessed a cohort with first-episode psychosis at presentation, 4 years later and 8 years later. We tested the critical period hypothesis by determining whether outcome stabilised between 4 and 8 years and duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) correlated with 8-year outcome. Additionally, as the influence of duration of untreated illness (DUI) has been debated from the dawn of the first-episode psychosis era Reference Johnstone, Crow, Johnson and MacMillan16 to the present day, Reference Malla, Norman, Schmitz, Manchanda, Béchard-Evans and Takhar13,Reference Clarke, Whitty, Browne, McTigue, Kamali and Gervin17,Reference Harris, Henry, Harrigan, Purcell, Schwartz and Farrelly18 we examined whether DUI had a relationship with 8-year outcome distinguishable from that of DUP.

Method

Setting and participants

The sample consisted of 118 participants in a prospective, naturalistic inception cohort study of first-episode psychosis in south-east Dublin, Ireland. We recruited all people with first-episode psychosis consecutively referred to the Cluain Mhuire Service and St John of God Hospital, Dublin, between February 1995 and February 1999. Reference Browne, Clarke, Gervin, Waddington, Larkin and O'Callaghan8,Reference Harris, Henry, Harrigan, Purcell, Schwartz and Farrelly18 Cluain Mhuire is a geographically defined catchment area service, providing community-based psychiatric care for an urban population of 165 000. Patients of Cluain Mhuire requiring admission are admitted to St John of God Hospital. Both out-patients and in-patients were recruited to the study. We defined first-episode psychosis as a first presentation to any psychiatric service with a psychotic episode. People who had started taking antipsychotic medication in another setting prior to referral were included as long as treatment had been ongoing for less than 30 days.

The 118 individuals discussed in this paper are those who received at presentation a DSM–IV diagnosis of non-affective psychosis: schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified; no cases of brief psychotic disorder were identified. 19 We included people with a history of substance misuse, but excluded those with substance-induced psychosis. The lower age limit for entry into the study was 12 years. There was no upper age limit.

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Hospitaller Order of St John of God. Verbal consent was obtained from each participant at presentation. The assessment process received approval from the research ethics committee as a best practice procedure, so every person meeting the criteria for inclusion was included in the study at presentation. We assessed each person with a broad range of standardised clinical measures at presentation, 4 years later and 8 years later. At 8-year follow-up, we obtained written informed consent from all participants.

Measures

Presentation assessments: 1995–1999

As soon as possible after first presentation, we measured psychopathology and insight with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Reference Kay, Fissbein and Opler20 When participants were clinically stable, we diagnosed each person and obtained demographic information using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV (SCID). Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams21 We completed the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), which is Axis V of the SCID. We assessed quality of life with the Quality of Life Scale (QLS). Reference Heinrichs, Hanlon and Carpenter22

We sought consent to interview each participant's family and from the family obtained collateral information on premorbid functioning, duration of prodrome and DUP.

With the Premorbid Adjustment Scale, Reference Foerster, Lewis, Owen and Murray23 we assessed each individual's premorbid social adjustment (PSA) during two discrete stages of their early life: age 5–11 (PSA1) and age 12–16 (PSA2). Because the time of life assessed by the PSA2 interview is often the age at onset of prodrome or psychosis, we used only PSA1 scores in our analyses.

Duration of untreated psychosis and duration of prodrome were measured using the Beiser scale. Reference Beiser, Erickson, Fleming and Iacono24 The individual and family were interviewed and a DUP obtained from each. When they disagreed, we came to a consensus figure based on the interviews and any sources of information available. When the participant did not consent to a family interview, we used the participant's interview and all other information. Onset of prodrome was defined as first noted deviation from the individual's normal premorbid functioning or the emergence of prodromal symptoms as described in the Beiser scale. Duration of prodrome was the time between the onset of prodromal symptoms and the onset of the first psychotic symptom. Duration of untreated psychosis was the period between the onset of the first psychotic symptom and the institution of antipsychotic treatment. Duration of untreated illness was the sum of the duration of prodrome and DUP.

Follow-up assessments: 1999–2005

During follow-up at 4 years (1999–2002) and 8 years (2003–2005), we repeated all presentation assessments except the Premorbid Adjustment Scale and the Beiser scale. We added the Strauss–Carpenter Level of Functioning Scale (SCLF), which allows separate evaluation of social and occupational functioning. Reference Strauss and Carpenter25 During follow-up, as far as possible given the demands of tracing, each interviewer remained masked to all previous assessments. Masking to DUP and DUI was strictly maintained.

For positive, negative and disorganised symptom scores, we used the PANSS sub-scales recently validated by van der Gaag et al. Reference van der Gaag, Hoffman, Remijsen, Hijman, de Haan and van Meijel26,Reference van der Gaag, Cuijpers, Hoffman, Remijsen, Hijman and de Haan27 Anyone who had scored no more than 3 on any of the 30 PANSS items over the previous month was said to be in remission; Reference Larsen, Moe, Vibe-Hansen and Johannessen28 we used this definition of remission when reporting 4-year follow-up results. Reference Clarke, Whitty, Browne, McTigue, Kamali and Gervin17

Inclusion in the 8-year analyses

At presentation 118 people were diagnosed with non-affective psychosis. Of these, 20 people (16.9%) refused consent for family involvement in the study. We did not have PSA1 scores for this group and we could not include them in our primary analyses; any analysis of the relationship between DUP, DUI and outcome must control for premorbid adjustment, the key confounder. Reference Verdoux, Liraud, Bergey, Assens, Abalan and van Os11 Of the remaining 98 people, 4 were known to have died by 8-year follow-up. At either 4-year or 8-year follow-up, 15 people refused further involvement and 12 people could not be traced. Therefore, we had three full data-sets for 67 participants (56.8%) and included them in the primary analyses. Fifty-one (43.2%) people were non-completers and were not included.

In the event that primary analyses showed no relationship between PSA1 and outcome, we performed secondary analyses in which we did not control for premorbid adjustment. There were 77 participants in these analyses (65.3%); 41 were excluded (34.7%).

Data analysis

We explored any differences between the completer and non-completer groups using univariate analyses. Because of positive skew, we log-transformed DUP and DUI to normalise them for analysis. We did not log-transform prodrome, which was also positively skewed, because the score for prodrome in 19 cases was zero and the log of zero is not calculable. Instead, we created a categorical prodrome variable: short (1 month or less), medium (1–12 months) and long (over 12 months).

We calculated the mean scores of all continuous outcome variables at 4 and 8 years, and compared mean 4-year and 8-year scores using paired-sample t-tests.

To identify independent predictors at presentation of 8-year outcome variables, we used linear or logistic regression modelling. When the outcome variable of interest was continuous (e.g. GAF, QLS), we built hierarchical linear regression models. We also used linear regression to identify predictors of change in continuous variables between 4 and 8 years. We built these models in a sequential chronological method described in a similar study. Reference Harris, Henry, Harrigan, Purcell, Schwartz and Farrelly18 When the outcome variable of interest was dichotomous (e.g. remission), we used binary logistic regression modelling (‘Enter’ method). In linear regression, the R 2 change statistic indicates the magnitude of the relationship between the independent and dependent variable; its equivalent in logistic regression is the adjusted odds ratio (AOR). Variables considered as independent variables were: age, gender, PSA1, years in education, lifetime history of substance misuse, duration of prodrome, DUP, negative symptoms, positive symptoms, disorganised symptoms, insight and presentation GAF. In each regression model, we included as independent variables all items with at least a trend level unadjusted association (P<0.10) with the dependent variable.

We repeated all regression analyses replacing DUP with DUI to establish whether including DUI rather than DUP improved the models. Given the high correlation between DUP and DUI (Spearman's rho=0.82, P<0.001), we did not include DUI and DUP in the same models. When DUP and DUI both contributed, in separate models, to a given outcome, we reported the better model. In linear regression, this was the model with the higher overall R 2 statistic; in logistic regression, that with the lower −2 log likelihood statistic.

In the event that DUP or DUI predicted a given outcome, we compared the means of that variable for long and short groups. For DUP, we made this division at three time points – 1 month, 3 months and 1 year – to identify precisely any clinically important cut-off point. We divided DUI at 6 months, 12 months and 2 years.

Results

Follow-up and characteristics of the sample

The mean duration of follow-up at 4 years was 42.0 months (s.d.=8.9, median=42); mean follow-up at 8 years was 95.3 months (s.d.=15.6, median=96). Table 1 compares the characteristics of completers (n=67) and non-completers (n=51). Completers were younger at onset (t=2.7, P=0.01) and more likely to be male (χ2=9.6, P<0.01). One person was under 16 at onset and none were over 65.

Table 1 Characteristics of completers (n=67) and non-completers (n=51) at first presentation

| Variable | Completers | Non-completers |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age at onset, years: mean (s.d.) | 24.4 (6.5) | 29.4 (12.4)** |

| Male, % | 73.1 | 45.1** |

| Education, years: mean (s.d.) | 13.7 (2.7) | 12.9 (2.6) |

| Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnosis | ||

| Schizophrenia/schizophreniform, % | 89.6 | 80.4 |

| Psychopathology | ||

| Positive symptoms score (range 1-55), mean (s.d.) | 22.8 (5.4) | 23.7 (6.4) |

| Negative symptoms score (range 2-62), mean (s.d.) | 16.6 (8.8) | 15.3 (8.6) |

| Disorganised symptoms score (range 10-70), mean (s.d.) | 25.4 (8.3) | 24.4 (8.3) |

| Insight score (range 1-7), mean (s.d.) | 4.8 (1.4) | 4.6 (1.4) |

| Lifetime substance misuse, % | 38.9 | 25.5 |

| Duration of untreated illness | ||

| Prodrome, months: mean (s.d.) | 30.5 (40.5) | 25.7 (38.3) |

| Prodrome, months: median | 8.0 | 11.0 |

| Duration of untreated psychosis, months: mean (s.d.) | 20.4 (22.8) | 28.6 (48.5) |

| Duration of untreated psychosis, months: median | 12.0 | 11.0 |

| Psychosocial functioning | ||

| Global Assessment of Functioning score, mean (s.d.) | 22.5 (9.0) | 22.5 (8.1) |

| Premorbid adjustment,a mean (s.d.) | 12.2 (4.3) | 10.8 (4.0)b |

Symptomatic outcome at 8 years

Thirty-three people (49.3%) were in remission. The mean positive symptom score was 11.6 (s.d.=6.1), the mean negative symptom score was 13.4 (s.d.=5.8) and the mean disorganised symptom score was 15.3 (s.d.=5.8); see Table 2 for sub-scale ranges.

Table 2 Comparison between 4-year and 8-year psychosocial and symptomatic outcomes with results of paired-sample t-tests

| Variable | Rangea | 4 years, mean | 8 years, mean | t-test | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial | |||||

| GAF | 0-100 | 59.6 | 64.1 | 2.4 | 0.02 |

| SCLF social | 0-8 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 2.5 | 0.01 |

| SCLF occupational | 0-8 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 1.5 | 0.14 |

| QLS, total | 0-126 | 83.4 | 84.0 | 0.23 | 0.82 |

| Symptomatic | |||||

| Positive symptoms | 1-55 | 12.1 | 11.6 | 0.83 | 0.41 |

| Negative symptoms | 2-62 | 16.6 | 13.4 | 5.0 | <0.001 |

| Disorganised symptoms | 7-70 | 16.9 | 15.3 | 3.5 | 0.001 |

Psychosocial outcome at 8 years

The mean GAF at 8 years was 64.1 (s.d.=18.6): 22 people (32.8%) scored 50 or less, denoting serious functional impairment; 19 people (28.3%) scored 51–70, indicating moderate impairment; 9 people (13.4%) scored 71–80, indicating mild impairment; and 17 (25.4%) scored 81 or over, indicating no impairment.

The mean SCLF social score was 5.3 (s.d.=2.0): 22 people (32.8%) scored 7 or 8, indicating frequent social contacts and close relationships. The mean SCLF occupational score was 4.8 (s.d.=2.8): 23 people (34.3%) scored 7 or 8, indicating that they were competent or very competent at full-time work or education.

The mean QLS score was 84.0 (s.d.=26.4, median=87, range 25–124). In terms of independent living, 17 people (25.4%) were living in unsupported accommodation; 44 people (65.7%) were living with parents or other family; 5 (7.5%) were in hostels or supported accommodation; and 1 person (1.5%) was homeless.

Change in outcome between 4 and 8 years

Table 2 shows mean 4-year and 8-year scores, with paired-sample t-tests to detect significant changes. Overall, 29 people (43.3%) were in remission at 4 years and 33 (49.3%) at 8 years; a binomial test with the test proportion set at 0.433 showed that the improvement to 0.493 by 8 years was not significant (P=0.18).

Predictors at presentation of 8-year symptomatic outcome

Remission was predicted by older age at onset (AOR=1.14, 95% CI=1.04–1.25, P<0.01) and shorter DUP (AOR=0.40, 95% CI=0.17–0.92, P=0.03). When DUP was divided at 1 month, 9 (82%) of the short DUP group (n=11) were in remission, but of those in the long DUP group (n=56), 24 (42.9%) were in remission (χ2=5.6, P=0.02).

The only predictor at presentation of positive symptoms at 8 years was DUP (R2 change=0.12, P<0.01). The short DUP group had fewer positive symptoms than the long DUP group when the cut-off was made at 1 month (8.4 v. 12.2, t=3.1, P<0.01) or 3 months (t=2.7, P=0.01). With a cut-off of 1 year, there was no difference.

Negative symptoms were predicted by DUI (R2 change=0.08, P=0.01). With DUI divided at 2 years, the short DUI group scored 4.4 points fewer than the long DUI group (F=11.1, P=0.001). Disorganised symptoms were predicted by younger age at onset (R2 change=0.14, P<0.01) and impaired insight (R2 change=0.06, P=0.03).

Predictors of 8-year symptomatic outcomes in secondary regression analyses

Upon removing PSA1 as an independent variable, the group included in analyses (n=77) was no different from those excluded (n=41) with respect to age at onset, but completers were more likely to be male (χ2=4.0, P=0.05). In secondary analyses, remission was predicted by shorter DUP (AOR=0.43, 95% CI=0.22–0.87, P=0.02) and female gender (AOR=3.4, 95% CI=1.2–9.8, P=0.02). There were no other differences between primary and secondary analyses.

Predictors at presentation of 8-year psychosocial outcome

Table 3 shows the trend level and significant unadjusted associations between presentation variables and 8-year GAF. The best regression model with GAF as dependent variable accounted for 40% of its variance and included DUI not DUP. The construction of this model from the variables in Table 3 is shown in Table 4. As shown, higher GAF was predicted by older age at onset, shorter DUI and preserved insight. With DUI divided at 2 years, the short DUI group scored 20 points higher than the long DUI group, indicating considerably better functioning (74.5 v. 55.1; F=24.7, P<0.001).

Table 3 Unadjusted associations, with P < 0.10, between presentation variables considered for inclusion in stepwise regression models and Global Assessment of Functioning at 8 years

| Variable | P |

|---|---|

| Duration of untreated illness | <0.001 |

| Duration of untreated psychosis | 0.001 |

| Age at onset | 0.001 |

| Premorbid social adjustment: age 5-11 (PSA1) | 0.01 |

| Time spent in education | 0.01 |

| Insight | 0.10 |

Table 4 Construction of the hierarchical stepwise linear regression model with 8-year Global Assessment of Functioning as dependent variable using variables in Table 3

| Step | Independent variable added | Model R2a | R2 change | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age at onset | 0.17 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| 2 | + Years in education + PSA1 | 0.17 | - | NS |

| 3 | + Duration of untreated illness | 0.35 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| 4 | + PANSS insight | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

Better SCLF social functioning was predicted by shorter DUP (R2 change=0.15, P<0.01), preserved insight (R2 change=0.11, P<0.01), older age at onset (R2 change=0.13, P=0.001) and female gender (R2 change=0.04, P=0.04) (total R2=0.43). Better SCLF occupational functioning was associated with older age at onset (R2 change=0.16, P=0.001) and shorter DUI (R2 change=0.07, P=0.02). Independent living correlated with older age at onset (R2 change=0.16, P<0.001).

The model with QLS total as dependent variable explained 42% of QLS variance. Higher quality of life was predicted by longer duration of education (R2 change=0.14, P<0.01), more insight (R2 change=0.08, P=0.02), older age (R2 change=0.14, P<0.01) and shorter DUI (R2 change=0.05, P=0.03). With DUI divided at 2 years, the short DUI group had a mean QLS of 96.1 against a mean of 73.6 for the long DUI group (F=17.3, P<0.001). None of these models changed in secondary regression analyses.

Predictors of change in outcome between 4 and 8 years

Duration of prodrome predicted change in negative symptoms, with shorter prodrome predicting improvement (R2 change=0.06, P=0.04). There were no predictors at presentation of change in likelihood of remission or other symptom dimensions. Shorter DUI predicted improvement in GAF score between 4 and 8 years (ΔGAF), when DUI was included in the regression model as a dichotomous variable divided at 2 years. Using log-transformed DUI, no predictors of ΔGAF were found.

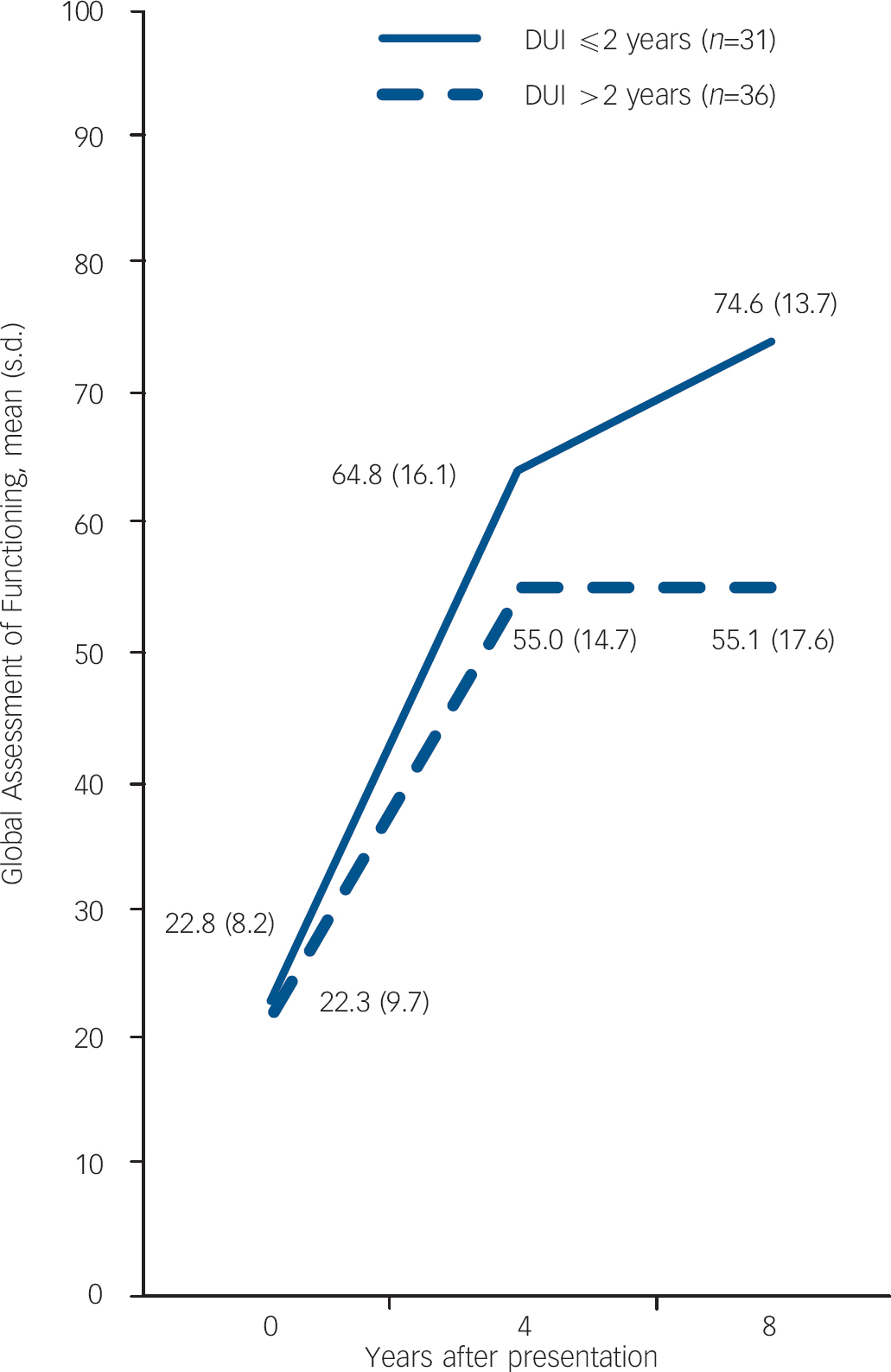

Duration of untreated illness at 2 years was the only presentation variable to predict ΔGAF (R2 change=0.10, P=0.01). Global Assessment of Functioning for those with a DUI of 2 years or less improved by 9.7 points, while for those with a longer DUI it improved by 0.1 points (F=7.1, P=0.01). Figure 1 shows mean GAF scores at 0, 4 and 8 years for the short and long DUI groups.

Fig. 1 Mean Global Assessment of Functioning by duration of untreated illness (DUI) group at 0, 4 and 8 years.

Change in QLS also correlated with DUI at 2 years only (R2 change=0.08, P=0.02). The QLS of the short DUI group improved by 6.7 points but that of the long DUI group deteriorated by 4.6 points (F=6.0, P=0.02).

We considered the possibility that total duration of illness, rather than DUI, accounted for differential psychosocial progression after 4-year assessment; participants with shorter durations of illness might not by then have reached a point of chronic stability relative to those with longer duration of illness. We rebuilt our models replacing DUI with total duration of illness, which we calculated by adding DUI to the duration of follow-up at 4-year assessment. Total illness duration (mean=88.0 months, median= 75 months) did not correlate with GAF or QLS change.

There were no predictors of 4- to 8-year change in SCLF.

Discussion

Eight-year outcome in first-episode non-affective psychosis

This first-episode psychosis cohort exhibited a variety of outcomes at 8 years. Psychosocially, 39% were functioning at a level that indicated social recovery, but a third had serious functional difficulties. Quality of life scores were mid- to high range. The proportion living independently was in keeping with the results of the Nottingham study at 13-year follow-up. Reference Mason, Harrison, Glazebrook, Medley, Dalkin and Croudace29 Symptomatically, half of our cohort were in remission and half remained symptomatic.

Change in outcome between 4 and 8 years

Between 4 and 8 years, GAF functioning slightly improved. On the SCLF scale occupational functioning did not change and social functioning marginally worsened. Symptomatically, the proportion in remission did not change. Negative and disorganised symptom scores improved but positive symptoms did not change.

The magnitude of change of any variable, as a proportion of its range, was small, and we suggest that any change for the cohort as a whole was of statistical rather than clinical significance. Thus, for the cohort as a whole, we do not contradict previous reports of stability after the early course of psychosis. Reference Carpenter and Strauss6,Reference Eaton, Thara, Federman, Melton and Liang7 However, there is a nuance in this apparent overall stability. Although GAF and QLS both essentially stabilised after 4 years for the cohort as a whole, it was possible to identify, at presentation, a group that would continue to recover beyond the critical period and a group that would not. For the former group, the hypothesis that there is a plateau of recovery post-critical period was not supported.

It was DUI that determined whether recovery would continue. With respect to functioning, there was no separation by GAF score between long and short DUI groups at presentation; there was a difference of 10 points at 4 years and at 8 years the difference was 20 points. Quality of Life Scale scores, meanwhile, deteriorated after 4 years for the long DUI group and improved for the short DUI group. These relationships were not confounded. There was no evidence of a diminishing effect of untreated illness with time.

Duration of untreated psychosis, DUI and 8-year outcome

Duration of untreated psychosis emerged as an independent predictor of 8-year outcome in non-affective psychosis. It predicted remission, positive symptoms and social functioning. It did not predict GAF, QLS, occupational functioning or independent living.

Our finding that DUP longitudinally predicted symptomatic and psychosocial outcomes disagrees with the findings of several authors. Reference Ho, Andreasen, Flaum, Nopoulos and Miller9,Reference Verdoux, Liraud, Bergey, Assens, Abalan and van Os11,Reference Craig, Bromet, Fennig, Tanenberg-Karant, Lavelle and Galambos12,Reference Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff and Giel15 It is, though, in keeping with the few other longitudinal studies that have measured the effect of DUP for 2 years or longer after presentation. Reference Addington, van Mastrigt and Addington10,Reference Bottlender, Sato, Jäger, Wegener, Wittmann and Strauss14,Reference Clarke, Whitty, Browne, McTigue, Kamali and Gervin17,Reference Harris, Henry, Harrigan, Purcell, Schwartz and Farrelly18 Regarding a DUP cut-off, symptom scores were lower if DUP was under 3 months, and remission more likely only if DUP was under 1 month.

Duration of untreated illness correlated more closely with psychosocial outcome than DUP. In this, our results paralleled those of Keshavan et al, who, defining DUI as we did, found that it predicted GAF and SCLF at 2-year follow-up. Reference Keshavan, Haas, Miewald, Montrose, Reddy and Schooler30 The association between DUI and outcome in their study persisted after controlling, as in our study, for premorbid adjustment. We found a 2-year cut-off for DUI consistently to correlate with 8-year morbidity.

It is not surprising that DUI should be a stronger predictor of psychosocial outcome than DUP; DUP is a stronger predictor of positive symptoms than DUI, while DUI is a stronger predictor of negative symptoms than DUP and negative symptoms are more strongly associated with psychosocial outcome than positive symptoms. Reference Munk-J⊘rgensen and Mortensen31–Reference Fenton and McGlashan33 What may be surprising is that the effect of DUI on outcome is reported rarely relative to that of DUP. Reference Malla, Norman, Schmitz, Manchanda, Béchard-Evans and Takhar13,Reference Keshavan, Haas, Miewald, Montrose, Reddy and Schooler30

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this study are its design, sampling and length of follow-up. We identified all in-patients and out-patients referred with psychosis to a geographically defined catchment area service over a period of 4 years. There were no initial refusals to participate. In terms of duration alone, there have been longer follow-up studies of outcome from the time of first presentation with psychosis. Reference Carpenter and Strauss6,Reference Eaton, Thara, Federman, Melton and Liang7,Reference Bottlender, Sato, Jäger, Wegener, Wittmann and Strauss14,Reference Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff and Giel15,Reference Munk-J⊘rgensen and Mortensen31–Reference van der Heiden and Hafner34 However, as a prospective study capable of examining the effect of DUP and DUI on outcome, independent of confounders, our duration of follow-up is equalled only by the EPPIC study. Reference Clarke, Whitty, Browne, McTigue, Kamali and Gervin17 Although the Munich study Reference Bottlender, Sato, Jäger, Wegener, Wittmann and Strauss14 reported that it controlled for premorbid adjustment, it measured adjustment in adulthood, and what was rated as poor premorbid adjustment may have been prodromal or early psychotic symptomatology. The 15-year Dutch study Reference Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff and Giel15 did not measure DUP systematically. Neither study discussed DUI.

Our principal weakness is that of the 118 people recruited with first-episode non-affective psychosis, 51 were not included in the primary analyses. Our ratio of completers to non-completers was comparable with that of the EPPIC cohort at 8 years, Reference Clarke, Whitty, Browne, McTigue, Kamali and Gervin17 the OPUS cohort at 5 years, Reference Nordentoft, Jeppesen, Bertelsen, LeQuack, Abel and Thorup35 and the Calgary cohort at 2 years, Reference Addington, van Mastrigt and Addington10 but the numbers in our primary analyses may have exposed our results to type II error. A related issue is selection bias: the participants included in our primary analyses were more likely than those excluded to be male and were younger at onset. Both male gender and young onset predict poor outcome, Reference Davidson and McGlashan36 and had we included the female and later-onset participants who were excluded from the primary analyses, our reported outcomes at 8 years might have been more favourable.

Our definition of remission Reference Clarke, Whitty, Browne, McTigue, Kamali and Gervin17,Reference van der Gaag, Cuijpers, Hoffman, Remijsen, Hijman and de Haan27 was not the definition proposed by the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group (RSWG). Reference Andreasen, Carpenter, Kane, Lasser, Marder and Weinberger37 We did not use these criteria because they were not published until 8-year data collection was virtually completed, and it was not possible retrospectively to apply them. Had we used the RSWG criteria, we may have found a lower rate of remission, as the RSWG criteria require a longer symptom-free period. The definition of remission used in our paper may have advantages over the RSWG definition in that it allows for a broader conceptualisation of the symptom dimensions that are important in psychosis. Reference Steel, Garety, Freeman, Craig, Kuipers and Bebbington38

A further limitation is that our data did not allow detailed assessment of the course of illness. We assessed participants at three time points and related variables at these time points to one another, but we did not examine course in the intervening periods (e.g. chronic v. episodic), as previous longitudinal first-episode psychosis studies did. Reference Eaton, Thara, Federman, Melton and Liang7,Reference Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff and Giel15,Reference Thara39

Additionally, we did not consider the type of onset of psychosis: acute, sub-acute or insidious. Type of onset relates to the period of time over which the participant develops frank psychotic symptoms, Reference Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff and Giel15 while DUP may include this period as well as the time between the emergence of frank symptoms and the institution of adequate treatment. Insidious onset predicts poor prognosis. Reference Röpcke and Eggers40 As insidious onset and longer DUP may be related, the relationship between DUP and outcome may be confounded by insidious onset. Some longitudinal first-episode psychosis studies that have controlled both for type of onset and DUP have found that insidious onset, rather than DUP, predicts outcome. Reference Wiersma, Nienhuis, Slooff and Giel15,Reference Röpcke and Eggers40

The critical period hypothesis, DUI and early intervention

Our median DUP was 12 months, so 4-year assessments took place a median of 4.5 years after the onset of psychosis. We took this as a reasonable point of demarcation for the end of the critical period. Although 2–3 years after onset was the duration suggested in the original paper, Reference Birchwood, Todd and Jackson1 other authors extended it to 5 years; Reference Garety and Jolley41,Reference McGorry42 indeed, years before the DUP era, Manfred Bleuler posited 5 years as the point beyond which outcomes stabilise in schizophrenia. Reference Bleuler43

The hypothesis that outcome stabilises after the end of the critical period was not supported. The main reason was not the marginal changes among the cohort as a whole but rather the marked improvement in functioning among a sub-cohort identifiable at presentation: the group with DUI of 2 years or less. The second premise of the critical period hypothesis was upheld. Duration of untreated psychosis predicted 8-year outcome after controlling for confounders; thus the predictive power of DUP was not an epiphenomenon.

As only one of the central premises of the critical period hypothesis was supported, and DUP was arguably not as important in predicting outcome as DUI, which was not mentioned in the original critical period paper, Reference Birchwood, Todd and Jackson1 do our findings weaken the case for early detection and intervention in psychosis? We conclude not, for four reasons.

First, although we did not find overall stability beyond the critical period, neither did we find deterioration; we found either stability or continued recovery. Had we found that deterioration ensued after 4 years, that would have undermined the case for early intervention, as recovery attained as a result of intervention during the critical period could not be expected to endure. Second, recovery after the critical period occurred for those with a short DUI, the sum of DUP and prodrome; continued recovery would be more likely among those detected early. Third, DUI independently predicted 8-year outcome. These findings support DUI reduction and maximal DUI reduction requires detection of impending cases of psychosis during the prodrome; the critical period could be extended to include the prodrome as well as early psychosis. Certainly, our results underscore the clinical potential of ultra-high risk (prodromal) research. Reference McGlashan44,Reference Ruhrmann, Bechdolf, Kühn, Wagner, Schultze-Lutter and Janssen45 However, although prodromal research is ‘increasing in maturity and sophistication’, Reference Cannon, Cornblatt and McGorry46 the case for prodromal detection is not yet strong enough to support widespread development of ultra-high risk services. Meanwhile, the practical strategy for reducing DUI is early detection and intervention in established psychosis. Reference Melle, Larsen, Haahr, Friis, Johannessen and Opjordsmoen47 The fourth reason that our findings do not weaken the case for early intervention is perhaps the most obvious: longer DUP independently predicted adverse outcomes 8 years after presentation. Short DUP groups had an advantage over long DUP groups in terms of remission, symptom severity and social functioning.

The decade since the critical period hypothesis was published Reference Birchwood, Todd and Jackson1 has seen evidence mount of harm done by untreated psychosis in the short term Reference Marshall, Lewis, Lockwood, Drake, Jones and Croudace48,Reference Perkins, Gu, Boteva and Lieberman49 and medium term. Reference Addington, van Mastrigt and Addington10,Reference Clarke, Whitty, Browne, McTigue, Kamali and Gervin17 What has not been clearly shown is that early intervention ameliorates this harm, Reference Marshall and Rathbone50 and we have not shown here that DUP reduction would improve 8-year outcome. Long DUP could yet be a proxy for insidious onset or some other unmodifiable determinant of outcome as yet not considered. Ultimately, this question will be answered by long-term randomised controlled trials of early intervention. While we await such trials, we cautiously propose that our findings show that a shorter DUP brings with it benefits that extend well beyond the critical period.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants and their families. Supported by the Stanley Medical Research Institute, Health Research Board and Science Foundation, Ireland.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.