Community-based storytelling activities are seen as important learning and leisure activities in many cultures (Young, Fenwick, Lambe, & Hogg, Reference Young, Fenwick, Lambe and Hogg2011). Such activities are regarded not only as a way to entertain and transfer knowledge, but also as a social context for community gatherings (Grove & Park, Reference Grove and Park2001). Storytelling activities have also been identified as both a vehicle for enhancing family literacy practices (Grieshaber, Shield, Luke, & Macdonald, Reference Grieshaber, Shield, Luke and Macdonald2012; Weigel, Martin, & Bennett, Reference Weigel, Martin and Bennett2005) and a strategy towards improved school literacy achievement (Dickinson, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, Reference Dickinson, Golinkoff and Hirsh-Pasek2010; Ehri et al., Reference Ehri, Nunes, Willows, Schuster, Yaghoub-Zadeh and Shanahan2001; Hart & Risley, Reference Hart and Risley2003; Mol & Bus, Reference Mol and Bus2011; Mullis, Martin, Foy, & Drucker, Reference Mullis, Martin, Foy and Drucker2012). In Western Australia (WA), one such community-based storytelling program is Better Beginnings (State Library of Western Australia, 2020), which is delivered via state-run libraries. This program provides literacy resources for parents so that they can support their children’s literacy development at home (Barratt-Pugh & Rohl, Reference Barratt-Pugh and Rohl2016; Leitão & Barratt-Pugh, Reference Leitão and Barratt-Pugh2018). These programs include rhyme and storytelling activities delivered at local libraries and free reading packs for parents of babies, toddlers, and kindergarten-aged children. Families are also able to borrow resource packs from these programs to use at home (State Library of Western Australia, 2020). Although these programs appear to be a successful conduit for early literacy goals for many young children in WA (Barratt-Pugh & Rohl, Reference Barratt-Pugh and Rohl2016), there is no specific encouragement for those with disability to attend.

There are a variety of reasons why individuals with disability are not included in community-based storytelling offerings but, essentially, such activities are seen as ‘unsuitable’ (Lyons & Mundy-Taylor, Reference Lyons and Mundy-Taylor2012; ten Brug, Van der Putten, Penne, Maes, & Vlaskamp, Reference ten Brug, Van der Putten, Penne, Maes and Vlaskamp2016), and text access without the assumed skill set seen as an ‘insuperable problem’ (ten Brug et al., Reference ten Brug, Van der Putten, Penne, Maes and Vlaskamp2016, p. 1044). These views on suitability rarely take into account that challenges around literacy development for children with disability are often as a result of barriers to early literacy, language, and communication development opportunities (Beukelman & Mirenda, Reference Beukelman and Mirenda2013; Kliewer, Reference Kliewer2008; Light & McNaughton, Reference Light, McNaughton, Soto and Zangari2009). For example, Kliewer (Reference Kliewer2008) asserted that deeply entrenched attitudes and assumptions about nonverbal (or less verbal) children with disability result in many not being given the opportunities to learn and experience literacy in ways that build on the capacities they already have (such as using picture symbols and adaptive/digital technology) for making meaning. These and other factors tend to cast children who are labelled with developmental disabilities on less-successful literacy trajectories than those of their typically developing peers (Sennott, Light, & McNaughton, Reference Sennott, Light and McNaughton2016). Nonetheless, increased expectation around literacy development (Browder & Spooner, Reference Browder and Spooner2011; Copeland, Keefe, & Luckasson, Reference Copeland, Keefe, Luckasson, Copeland and Keefe2018; Grigal, Hart, & Weir, Reference Grigal, Hart, Weir, Agran, Brown, Hughes, Quirk and Ryndak2014; Keefe & Copeland, Reference Keefe and Copeland2011; Moni & Jobling, Reference Moni, Jobling, Faragher and Clarke2014) and an emerging movement towards presuming competence for ‘all’ learners (Biklen & Burke, Reference Biklen, Burke and Davis2018; Kliewer, Biklen, & Kasa-Hendrickson, Reference Kliewer, Biklen and Kasa-Hendrickson2006) has seen a recent upsurge in interest in community-based storytelling for individuals with disability (ten Brug et al., Reference ten Brug, Van der Putten, Penne, Maes and Vlaskamp2016).

It is generally acknowledged that access to literacy instruction for students with disability requires considered thought around how materials and activities are represented (Ashman, Reference Ashman2018). Aligned to this thinking, ten Brug et al. (Reference ten Brug, Van der Putten, Penne, Maes and Vlaskamp2016, p. 1044) challenge the notion that literacy texts are simply about developing intellectual engagement, claiming that their ‘purpose and function’ is additionally related to emotional engagement and creativity. Grove (Reference Grove and Fornefeld2011, p. 36) believes that ‘senses and feelings’ precede comprehension of storytelling text, and it is in this space that thoughtful and creative techniques can impact on all learners (Young et al., Reference Young, Fenwick, Lambe and Hogg2011). Consequently, a range of storytelling strategies have emerged for individuals with disability, including interactive storytelling (a strong focus on prose and the rhythm of language; Park, Reference Park2004), story-sharing (techniques for developing personal stories; Grove, Reference Grove and Fornefeld2011), sensitive stories (individual stories on sensitive matters; Young et al., Reference Young, Fenwick, Lambe and Hogg2011), and multisensory storytelling (MSST; stories that include a variety of individualised sensory stimuli; Grove & Park, Reference Grove and Park1996; Park, Reference Park1998). Of these, it is MSST that has been most extensively developed for individuals with disability (Preece & Zhao, Reference Preece and Zhao2015; ten Brug, Van der Putten, & Vlaskamp, Reference ten Brug, Van der Putten and Vlaskamp2013).

Typically, with MSST, the story or rhyme commences with a reference to stimuli to activate awareness for the listener (Lambe & Hogg, Reference Lambe, Hogg and Fornefeld2011). The stimuli can be personalised and, unlike a typical storytelling session relying on engagement via voice (auditory) and pictures (visual), MSST sessions are designed to activate nearly all of the senses. Ten Brug et al. (Reference ten Brug, Van der Putten and Vlaskamp2013, p. 1045) describe the use of a toy tambourine to herald the commencement of a short individualised MSST for a young person with complex needs, followed by interactions with perfume, streamers, a microphone, and a balloon — all designed to create engagement with the storyline. Hence, MSST typically employs a universal design for learning approach, whereby multiple means of representation and engagement potentially enable learners to access content in a variety of ways (Dixon, Reference Dixon2008; Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, Reference Meyer, Rose and Gordon2014; Ok, Rao, Bryant, & McDougall, Reference Ok, Rao, Bryant and McDougall2017). Existing studies support the efficacy of MSST for individuals with disability, including those with complex needs (Matos, Rocha, Cabral, & Bessa, Reference Matos, Rocha, Cabral and Bessa2015; ten Brug et al., Reference ten Brug, Van der Putten, Penne, Maes and Vlaskamp2016); however, it has been suggested that the way MSST is currently conceptualised may place restrictions on the variety of approaches that can be utilised and does not focus on a text-rich literacy experience (Preece & Zhao, Reference Preece and Zhao2015) essential for emergent literacy learners (Rose, Reference Rose2006).

This article reports findings on an approach to MSST and rhyme activities that were developed for students with disability in WA based on current library programs supporting early literacy development. This program utilised music, props, and imaginative play to engage children in the storytelling or rhyme activities. Specifically, the presenters were trained performing artists whose presentations involved elaborate set production and a variety of props to reinforce elements of the story or rhyme. Tactile and kinaesthetic experiences, along with specific scents and a constant narrative via spoken word, rhyme, song, and rhythms, were used to engage children in the story. The children in attendance, all of whom had a recognised disability, were encouraged to participate at a level they were comfortable with. The rationale for the study was to review the benefits of such an approach for students with disability and their families. The research sought to answer the following questions:

-

1. In what ways do children with disability engage with MSST and rhyme experiences?

-

2. In what ways do these multisensory experiences impact on families of children with disability?

Data were collected through a series of multisensory session observations, focus group interviews with parents of participants, and interviews with performing artists.

Method

Design

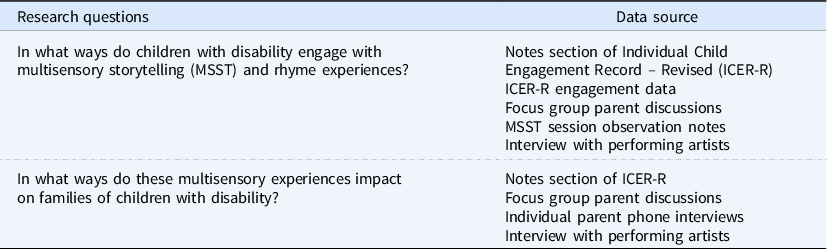

We adopted a direct observation multiple case study methodology, enabling the researchers to explore specific contexts in detail (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln, Guba, Huberman and Miles2002; Yin, Reference Yin2009). Researchers gathered data on the engagement of children in the MSST and rhyme sessions using a range of data collection methods (Punch, Reference Punch2005; Thomas, Reference Thomas2003), as multiple qualitative methods have the potential to generate more complete explanations of the phenomena being observed (Morgan, Pullon, Macdonald, McKinlay, & Gray, Reference Morgan, Pullon, Macdonald, McKinlay and Gray2017, p. 1060). To improve the validity of the findings, data were triangulated (Denzin, Reference Denzin2009) by comparing the observations of the different members of the research team and by utilising several data collection methods. Table 1 identifies the sources of data used to capture the experience of participants in authentic ways and to answer the research questions. Once ethics approval was obtained from the Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Committee (ethics approval number 18475), data collection commenced. The researchers acted as observers and did not interact with the participating children post the multisensory story and rhyme sessions. It is acknowledged that this presented as a missed opportunity to collect data; however, extensive observation notes of the participating children accompanied the Individual Child Engagement Record – Revised (ICER-R; Kishida, Kemp, & Carter, Reference Kishida, Kemp and Carter2008) engagement data.

Table 1. Data Collection in Relation to the Research Questions

Researchers observed two six-session programs that involved two performing artists presenting separate sessions of storytelling, in which a well-known children’s story was delivered, and rhyme activities, where a selection of familiar rhymes was presented to a small group of children with disability and their parents and siblings. Two different groups were involved in these sessions. The storytelling sessions were presented in a hired special education school space, and the rhyme activities were presented in a community therapy setting. Researchers observed participants (children, families, and performing artists) during each session using the ICER-R (Kishida et al., Reference Kishida, Kemp and Carter2008). At the conclusion of the program, and in line with previous case study research (Curry, Nembhard, & Bradley, Reference Curry, Nembhard and Bradley2009; Walshe, Ewing, & Griffiths, Reference Walshe, Ewing and Griffiths2012), qualitative data collection methods were employed. These included a semi-structured interview with the performing artists to explore their experiences and perceptions. Additionally, focus groups were conducted with parents to gain their perceptions of the experience and to determine the potential benefits for their child and family. The quantitative and qualitative observational data related to both research questions, affording the opportunity to correlate data in order to address the questions.

Participants

Three target groups were involved in this research: children taking part in the program, families of the children, and the performing artists who delivered the multisensory story and rhyme activities. Informed written consent was collected from the performing artists and parents participating in the study, and parents provided consent for their children to participate prior to data collection.

The children were drawn from three groups involved in the multisensory experiences: Group 1: six from a support group for children aged 2–10 years with autism spectrum disorder (ASD); Group 2: three children with ASD aged 2–4 years from a therapy service provider; and Group 3: eight children aged 6 months–10 years with Down syndrome. All 17 children from these groups were observed during the multisensory sessions that they attended. Aliases are used in the Results section to describe some of these participants. Additionally, 12 parents were interviewed in focus groups and another two parents were interviewed individually via phone as they wanted to provide input but were not able to attend the focus groups. Finally, the two performing artists were interviewed using semi-structured interviews. One was a trained teacher with a specialisation in special education, who held a role as a special education assistant. The other artist had experience working with individuals with disability and had completed some training in early language, literacy, and communication development.

Instruments and Data Analysis

Engagement was prioritised as an area of focus for this study, given the recognition that it is an essential foundation for successful learning and skill development for all children (Carpenter, Carpenter, Egerton, & Cockbill, Reference Carpenter, Carpenter, Egerton and Cockbill2016; Dykstra Steinbrenner & Watson, Reference Dykstra Steinbrenner and Watson2015; Keen, Reference Keen2009). Following an audit of possible engagement tools, the ICER-R was selected because its reliability and validity has been established for use with children with a broad range of disability (Kishida et al., Reference Kishida, Kemp and Carter2008). It is important to note that data collected from direct observations are considered to be a ‘class of their own’ (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Pullon, Macdonald, McKinlay and Gray2017, p. 1061), as they allow the researcher to report on what they have seen, rather than what others say they have done. Murphy and Dingwall (Reference Murphy and Dingwall2007) describe direct observation as ‘the gold standard’ (p. 2230) of data collection techniques; however, Morgan, Pullon, and McKinlay (Reference Morgan, Pullon and McKinlay2015) and Morgan et al. (Reference Morgan, Pullon, Macdonald, McKinlay and Gray2017, p. 1062) lament that often such data take ‘a back seat’ to that collected during interviews. In this research, direct observations were given precedence when determining the level of children’s engagement. However, indications of the impact of these sessions on families was also highly valued, as parents had knowledge of their child’s engagement behaviours in a range of contexts.

Engagement observations using ICER-R (Kishida et al., Reference Kishida, Kemp and Carter2008)

An advantage of the ICER-R in this current research was that it combined both quantitative data, through partial interval time sampling, and qualitative data, through recorded observations. Using the ICER-R, observers record the types of engagement children exhibit, who they are interacting with, and whether any physical prompts were involved, at 15-second intervals as outlined in Kishida and Kemp (Reference Kishida and Kemp2010). In this research, two researchers observed two separate six-session programs. Within these programs there were 12 observation blocks, and the researchers reported on 851 separate intervals (for a total of 7.1 hours of observation).

The researchers recorded engagement types identified in the ICER-R as active engagement, passive engagement, active non-engagement, and passive non-engagement. The ICER manual (Kishida & Kemp, Reference Kishida and Kemp2009) provides definitions of the engagement types, which the researchers refined to suit the context of these observations (see Table 2).

Table 2. Engagement Descriptors (Kishida & Kemp, Reference Kishida and Kemp2009)

To ensure interrater reliability, the researchers practised the observation and recording process by recording observations from a videoed MSST session prior to beginning data collection. The researchers discussed their observations in order to reach consensus on what behaviours constituted the range of measured engagement. Once consensus was reached, the researchers undertook an additional round of observations during the multisensory sessions. To confirm interrater reliability, researchers worked in triads to ensure that all researchers had undertaken observations with each other and there was consistency in the coding of observations. These sessions were examined for mean interobserver agreement for the level of engagement across storytelling and rhyme activities and were found to be consistently high, 87.5% (range: 83–91.5%). In addition, during the remaining data collection sessions, two researchers observed the same child and compared observations post session.

The observation notes from the ICER-R were subjected to detailed analysis to identify the way that children engaged with the multisensory experiences. Over the six observation sessions, 17 children were observed using the ICER-R. Six children were observed in all six sessions, three children were observed in five sessions, three children were observed in four sessions, and five children were observed in one session only. This inconsistency of participants was simply a result of which individuals presented for each weekly multisensory session, as this varied.

The Shared Reading Self-Evaluation and Observation form, a checklist resource utilised extensively in Project Core (a modulised program focused on improving academic achievement of students with significant cognitive disability; Geist, Reference Geist2020), was used to record evidence of good shared reading practice. Such features include individual communication system support, scaffolding of previous storytelling and rhyme sessions, and modelling of reading using a variety of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) styles (Center for Literacy and Disability Studies, 2021).

Interviews and focus groups

Importantly, the observation data in the current research was used to inform follow-up interviews with the performing artists and parents who were present as observers/supporters in the multisensory sessions. The interviews with the performers focused on their experiences and perceptions of the program (see Appendix A for interview questions) and their insights regarding the program’s implementation.

As parents participated in the program, their views and perceptions were key sources of data. One focus group comprised three parents, another comprised seven parents, and finally two parents were interviewed and recorded over the phone. The parents were asked about their perceptions of the program and what they believed their children gained from the experience (see Appendix B for focus group interview questions).

Interviews with performing artists and parents were recorded, transcribed, and analysed using NVivo software Version 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2018), following Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña (Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014) protocols. Transcripts were initially organised in relation to the guiding questions and then in relation to the emerging themes. They were further analysed by repeated readings and consideration of the research questions. Finally, all researchers read through the transcripts in order to reach consensus on the key themes.

Results

In What Ways Do Children with Disability Engage with Multisensory Storytelling and Rhyme Experiences?

Data from the ICER-R indicated that, on average, children were engaged in multisensory story and rhyme experiences for 79.6% of the time, with 54.4% of that time being observed as active engagement and 25.2% being passive engagement. Table 3 describes the average percentages for the four types of engagement and the physical prompts observed to encourage participation (28.7%). Figure 1 presents the individual engagement levels of six of the 17 observed participants. These participants, who represented a cross-section of disability, were selected as they had been observed using both researchers’ observations on a minimum of four observation periods (Aimee) and a maximum of 14 observation periods (Farran). With the exception of Cameron (observed in six observation periods), who was either actively engaged or disengaged, the participants regardless of age or disability type tended to be engaged during the sessions. The low level of passive non-engagement observed by the researchers suggested that even the younger students with complex communication needs were often observing the performers and fellow participants.

Table 3. Participant Average Percentage for Engagement Types and Physical Prompts for the Multisensory Arts-Based Experience

Note. Total observed intervals N = 851. AE = active engagement; PE = passive engagement; AN = active non-engagement; PN = passive non-engagement.

Figure 1. MSST Participant Frequency of Engagement Types.

Note. AE = active engagement; PE = passive engagement; AN = active non-engagement; PN = passive non-engagement.

Researchers also recorded interactions with performers, family/carers, and peers and these varied depending on the activity and the age of the students observed (Figure 2). Although there was little observation of interaction from the participants with each other, this is more likely a result of unfamiliarity with each other and the range of age-related social skill development than the intent of the performers. Interview findings from parents support the ICER-R observations, suggesting that children with disability engaged in the multisensory story and rhyme sessions via interaction with the performing artists and the stimulus materials provided (and where necessary the support of their family/carers).

Figure 2. Interactions with Peers, Performers, and Family/Carers.

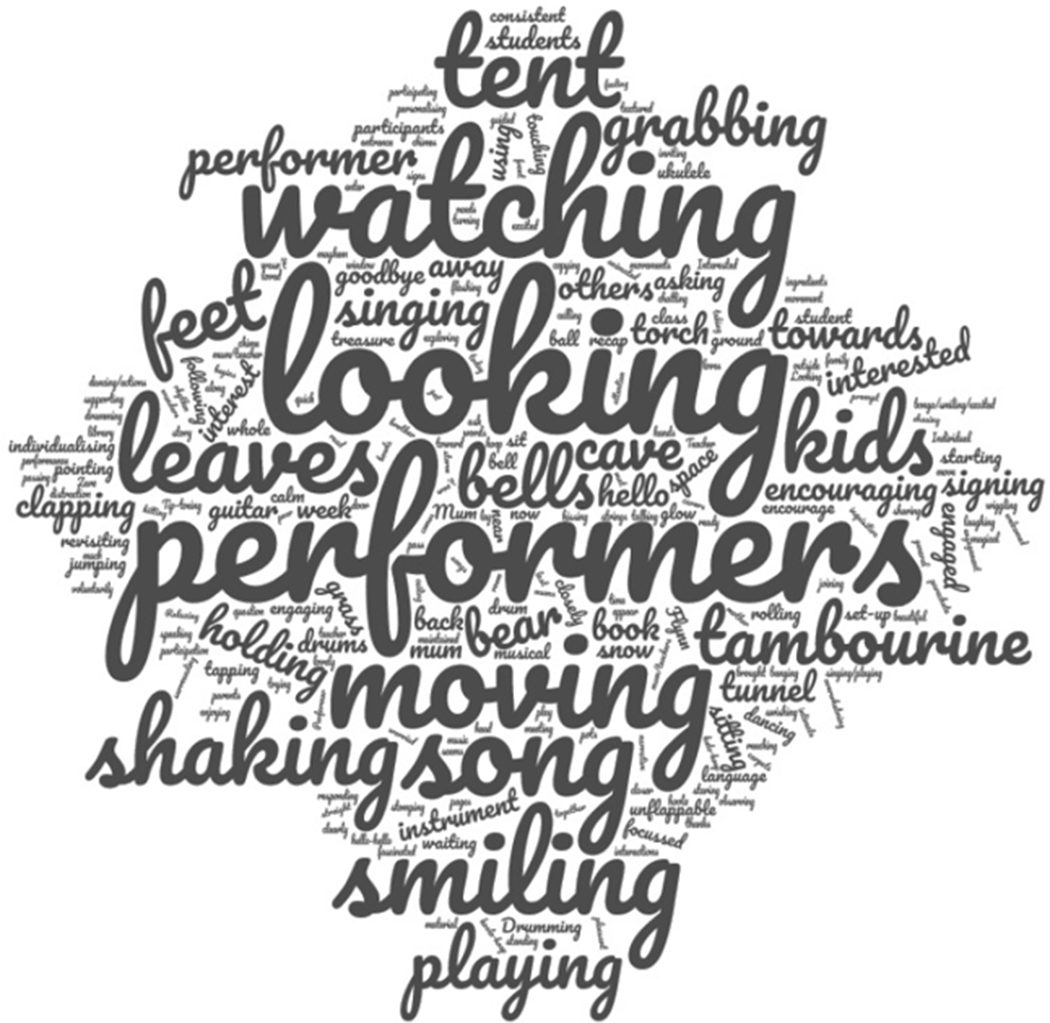

The researchers’ ICER-R observation notes are further presented in Figure 3. These observations were placed in a word cloud, where the most commonly used describing words appear in larger text. The most frequently occurring words are indicative of engagement, with ‘looking’ and ‘watching’ being the most commonly used adjectives, followed by ‘moving’, ‘shaking’, and ‘smiling’. Musical instruments, such as bells and tambourines, and props, like a tent/cave and autumn leaves, complete the picture of what the researchers observed during these multisensory story and rhyme sessions.

Figure 3. ICER-R Observations in Word Cloud Form.

The overall observational findings highlight the engagement process enacted during the multisensory story and rhyme sessions, beginning with the opportunities for positive interaction. Typically, within the observed sessions, the researchers described participant interaction as being built around guidance from the animated performers and via the tactile and kinaesthetic experiences that were presented. The participants followed the performance narrative in some cases with obvious intent; for example, during the storytelling sessions for Group 1 (taken from the researchers’ notes), Raymond ‘tip-toed towards a cave in response to the performers’ requests’, and others, such as Farran and Ivan, ‘shook bells’, ‘flashed torches’, ‘swished through grass’, and ‘stomped on leaves’, mimicking the performers. Equally, in a rhyme session, Robby was fascinated with the pots and ingredients and, when invited, delighted in the opportunity to pour and stir in order to make the ‘pease pudding’. The active engagement could be described as responding to the stimuli and activities presented.

Performance skills to enhance multisensory experience

Researcher observations noted that the performance skills utilised by the performing artists facilitated engagement. The ‘performers created a magical environment’, that enhanced the participants’ engagement and had the potential to support their language development. The performers utilised carpets, cushions, blankets, and throws with a variety of textured materials. An assortment of props, such as tents, strands of fairy lights, and buckets of autumn leaves, established a purposely designed space that was observed to be ‘inviting, calm and intimate’. Before the participants arrived, the performers sprayed essential oils (a low-level scent) around the performance area, which was noticeable but not overpowering. When the participants arrived, the performers were in place, the set-up was ‘calm, and inviting engagement via light percussion and welcome songs’.

Each session started with a performer casually playing percussion on bongo drums. The rhythm was slow and calming. The performers were both at ground level. Upon arrival, the ‘performers engaged with kids as they entered the room’. The performers played ukuleles to individually welcome each child by name, via the ‘hello song’. This was noted by the researchers as a way to gently reconnect: ‘during the welcome song, Raymond participates straight away drumming and smiling’. Ukuleles, tambourines, bells, and chimes were accessible on the floor, and the children were observed ‘hitting the drums’, ‘shaking tambourines’, ‘mimicking the performers on the ukulele’, ‘taking a chime from the performer’; the musical aspects appeared to be the gateway to participating in the performance.

Parents felt that music played an important part in their children’s experience and enjoyment of the multisensory sessions. One described the multidimensional impact of the program on her 7-month-old child:

He’s only seven months old but he’s so engaged in it, he loves it. The different textures, shapes, colours, everything. He just loves it. Music is his thing too, just like the other kids and I just think it’s good even from that young age being able to do this type of thing. I think it’s really helping him a lot.

The performing artists’ storytelling and rhyme activities appeared designed to provide opportunities to engage the children via imaginative play strategies. In a rhyme session, through the manipulation of a soft toy representing a character in the rhyme, the performers attributed the bear with feelings. As experienced performing artists, they appeared adept at improvising when necessary. As one performing artist explained, ‘We have a basic structure, but within the structure there’s room to move and improvise and respond to the kids and what they’re enjoying. We can continue something longer and if something’s not working, we wrap it up’.

Support for communication and emergent literacy

The performers were sensitive to nonverbal communication. For example, they provided appropriate wait time and prompts to encourage participation, provided repetition of keywords, delivered an enthusiastic and joyful experience around reading, and opened some sessions with key word signs. However, it became apparent to researchers that opportunities to develop both communication and emergent literacy were missed during the sessions. Completion of the Shared Reading/Performance Self-Evaluation and Observation form (Center for Literacy and Disability Studies, 2021) during each observation session indicated that strategies to develop emergent literacy skills, such as individual communication system support, scaffolding of previous storytelling sessions, and modelling of reading using a variety of AAC styles, were not employed. Increased communication accessibility would have allowed for greater engagement, participation and development of the children’s emerging language, literacy, and communication skills. Some examples from the researchers’ observation notes included:

-

‘This week was a repeat of Twinkle Twinkle Little Star. There was a nursery rhyme specific Aided Language Display (ALD) in the room. It was lying on the floor in front of the backdrop, though it was not used during the session to model language’.

-

‘The session provided lots of (missed) opportunities to repeatedly model the use of key words with signs or symbols’.

-

‘A visual picture schedule was on display at the start of the session but was not used by the performing artists during the session’.

-

‘The performing artists were enthusiastic in their delivery in a way that fostered joy in the rhymes — it would be wonderful to see them connect this enthusiasm for the rhymes with the texts to incidentally build concepts about print and joy of shared reading activities’.

Further, there appeared to be restricted opportunity to interact with the reading material and, although the text was the cornerstone of the storytelling activity, the sessions were more about engagement with the performance experience. The book itself appeared simply as another prop. Likewise, in the rhyme sessions, while the oral repetition of keywords and phrases was evident, no written text was used. Opportunities to develop literacy were missed because of the focus on experiential engagement.

In What Ways Do These Multisensory Experiences Impact on Families of Children with Disability?

Evidence from parent interviews and researchers’ observation notes suggest the multisensory experiences appeared to have a positive impact on the families of children with disability. As the program progressed, parents noticed their children concentrating for longer periods of time and on particular props used by the performing artists. One parent described her 5-year-old child’s improved focus that she believed was developing with each sensory storytelling session. She said,

It’s just really wonderful seeing the kids light up. Especially my son, I could see him focusing more and more, which is something that’s new as well for him, and he’s not focusing for a few seconds, he’s really concentrating. These are little milestones that the sessions really, really helped with. I think it’s encouraging. These are the things, the little things, that make a big difference.

Another parent described how music helped to keep her son (7 years) focused and engaged in the experience. She said, ‘He doesn’t like to stand still. But if there’s music it helps’. Out of all 10 parents involved in the program, nine concluded that the inclusion of music was particularly effective in encouraging and stimulating their children’s language development. One stated, ‘Language development is huge especially in the early years. Music is an even better way to get it [language development] across and, especially for our kids, the sensory input has been brilliant’.

Parental enjoyment

Parents also reported feeling comfortable in the space and found the sessions to be enjoyable. Parents were able to relax knowing they were not being judged or had to worry about their child’s behaviour. Four of the families had experienced storytelling and rhyme offerings via their community libraries and discussed their impressions of both programs:

Most Wednesdays we go down to story time at the library and they normally start with a couple of songs and basic nursery rhymes then read a story, do a couple more songs and do a craft. So, there is that little bit of sensory input into it but it’s not like this. If you were to compare them, this is so much more in-depth and you’ve got so many more perceptions. Like with Twinkle Twinkle, the performers put stars over them and let the kids feel tinsel. This is much more beneficial for our kids.

One parent described her experience of story time at the library as ‘way too stressful’ as her son received too much negative attention. The parent said,

These guys [performers] know how to engage our kids. They know he needs to move around and can’t be made to sit still. The other kids in these sessions are similar and so you feel more relaxed. When you take them to the other things you get the judgemental looks — like ‘control your child’ sort of thing.

A parent described how she had previously felt excluded due to her language barrier, but this was not the case during the multisensory sessions described herein:

I enjoyed myself as well, not just [student name]. I liked singing the songs. I’ve learned new songs and not just from Brazil, all these nursery rhymes. Sometimes I feel left out because I don’t know those songs. This was different. I enjoyed myself. It was fun even playing with the other kids.

The performing artists reported that storytelling and rhyme sessions were specifically designed to incorporate the parents in the multisensory experience. They explained that, by sharing the experience with parents, they anticipated that similar activities could be replicated at home. Parents confirmed that they had learnt new ways of engaging their children in rhymes and stories. A parent explained, ‘He’s touching things. That water one is the best. I can do that at home’. Another parent described her enjoyment at seeing her child having fun and the opportunity to gain new ideas. She said, ‘It’s hard coming up with something creative every day and I feel sometimes I’m neglecting them by giving them the iPhone or having the TV on. Getting some ideas and doing something quite different has been wonderful’.

All parents described how they had learned new ideas and ways to play with their children due to the multisensory experiences. Three parents expressed their thoughts on developing new ways to engage and connect with their children:

I’ve seen what ignites his interest so I’m now singing to him while I’m playing rather than just doing the rattle thing or playing with little toys.

I’m trying to remember songs and get him involved in a bit of messy play because it seems to ignite something in him so, yeah, he’s doing really well. And he loves it. He loves the sensory group so if there was more we’d be a part of it.

The memories of the activities that I’ve done here, I’ve taken home over the last six weeks. If I didn’t have that, he wouldn’t be engaged in all of these things because I wouldn’t be doing it with him and I wouldn’t have all these great ideas.

The parents appreciated the opportunity their children had to experience a range of activities and engage with different senses that they did not have the time or capacity to facilitate at home.

All parents described a side benefit of the multisensory experience was seeing their child and their siblings interact in positive ways. One parent explained, ‘Being interactive with her little brother is so good. I can see her light up even more as she has learned new games to play with him’. The parent went on to describe the excitement the sibling also felt and their enthusiasm to try some of the activities at home. She said, ‘Her sister was asking to get some pom-poms and cut them all up and scatter them on the carpet. Yeah, that’s awesome to see that interaction’.

Discussion

Evidence from the analysis of the ICER-R observations and the parent interviews suggest that students with disability engaged with the storytelling and rhyme experiences through the use of multisensory stimuli and strategies. Parents reported positive interactions between their children and the performing artists and an improved capacity to focus on the activities as an outcome of the engagement process. In addition, the inclusion of siblings was seen as beneficial for the family, with parents describing their enjoyment in seeing their child and their sibling(s) interact so positively. The stimulating multisensory environment, including elements of the five senses, was identified as a factor in the observed engagement of the children.

The researchers’ observation notes suggest that the performing artists’ style and skills were important in facilitating these multisensory techniques. The flexibility afforded in their methods allowed for spontaneous adjustment to meet the needs and responses of the children, consistent with acknowledged MSST practice (Preece & Zhao, Reference Preece and Zhao2015). As described by Fowler (Reference Fowler2008), the elaborate sensory environment that performing artists create is an integral MSST component. In addition, their vocal and movement skills ensured that the children were guided gently and sensitively through the activities. Parents reported that the music was also key to the children’s engagement in, and enjoyment of, the program. In addition, they felt the music supported their child’s language development, consistent with research on music’s impact on neural and language development (Jantzen, Large, & Magne, Reference Jantzen, Large and Magne2016; Thaut, Reference Thaut2008).

Given the positive experiences generated for participants, it is worth reflecting on whether more could be done to create opportunities for communication and emergent literacy. With Better Beginnings’ goal of inspiring ‘a love of literacy and learning for all W.A. children by encouraging families to read, talk, sing, write and play with their child every day’ (State Library of Western Australia, 2020), it appeared that the sessions described herein, while being high-level performance and play pieces, needed more investment in the ‘love of literacy and learning’ aspects. In order to add value to this experience, the performers could ensure that the storybook or selected keywords and phrases were consistently visible and accessible if their goal was development of print knowledge, a necessary precursor to reading (Piasta, Reference Piasta2016). As with Better Beginnings, some consideration could be given to a take-home pack, with books and resources from the multisensory activities.

As much as relatively high levels of engagement were recorded and the sessions were very well received by the parent group, further thought is required around appreciating what student engagement in the storybook and rhyme printed words might look like, and what forms of communication access might be required to support this engagement. There appeared to be a disparity between the espoused intentions of the performers to enhance the participants’ literacy and the lack of consistent pedagogy required to achieve this. Thus, the storybook in the MSST sessions appeared only as a prop. Inadvertently, the performers reinforced the seminal observation of Light, Binger, and Kelford Smith (Reference Light, Binger and Kelford Smith1994) in which emergent literacy skills for individuals with disability are impacted by the passive nature of their story-reading experiences. In contrast, Better Beginnings is clear that ‘regular exposure to new words … boost[s] … vocabulary and conversation skills’ (State Library of Western Australia, 2020). Parents described glowingly how these sessions were tailored perfectly for their children, and yet there is evidence that more could have been provided in terms of literacy development. Thus, anyone thinking of facilitating similar multisensory experiences should consider the inclusion of language text supports to encourage early literacy development.

There is much to be gained from children with disability participating in the multisensory story and rhyme activities observed and described; however, in isolation, these programs may inadvertently maintain ableist views that the only way to address difference is through keeping learning experiences separate (Slee, Reference Slee2013). The enjoyment that the siblings without disability gained from being involved in these sessions suggested that combining the performance creativity and expertise observed in the multisensory story and rhyme sessions with existing community offerings could create programs with universal design (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Rose and Gordon2014) appeal that could make a difference for all young learners. This would be particularly the case if all involved undertook professional opportunities to develop AAC skills and know-how, received specific training via the State Library of Western Australia around emergent literacy, and, most importantly, responded to the voice of those excluded from existing community programs.

There are obvious limitations to the study, including the small number of participants and the subjective nature of interview data. In addition, not all parents were available to be interviewed and the time-sampling method used in the ICER-R only provides an estimate of engagement. As a case study, these findings cannot be generalised to other settings; however, including information from a range of sources provided a rich description of the experience for the participants in this context. This description illustrates that an arts-based approach to MSST is engaging for students with disability. Further, this study may provide the impetus for larger-scale research into the relative benefits of arts-based, over text-based, MSST.

Conclusion

The arts-based multisensory story and rhyme program was found to have a positive impact on families, with participation proving enjoyable and stimulating for all members. Parents and performing artists acknowledged the design of the program to build family capacity, and parents reported learning new ways in which they could engage their children at home. Parents also appreciated the inclusive non-judgemental attitude of the performing artists and being among families with children with similar needs, as it enabled them to relax and enjoy themselves. Thus, it could be suggested that learning opportunities were enhanced via the general engagement of all participants. However, providers of early literacy events, such as sensory storytelling or rhyme activities need to be aware of the unconscious bias that may occur with these literacy events if they are planned specifically for young children with perceived disability and difference.

Although a broader understanding of literacy as social practice can afford young children with disability greater access to literacy than a narrower skills-focused approach, the need for interaction with text must be appreciated. It is necessary to broaden the understanding of the multimodal ways in which young children with disability may be engaged and communicate during literacy events. Access to the necessary artefacts of literacy must be provided, as well as support for the tools that allow for some with disability to communicate more effectively in community settings. Ideally, community models focused on emergent literature could combine the engaging, supportive, and welcoming practice witnessed by the researchers, with quality early literacy instruction.

Financial support

This research was supported by a grant from Sensorium Theatre Inc.

Appendix A

Performing Artist Guiding Questions

-

1. Can you tell me about your prior experiences/training or working in the arts?

-

2. Can you describe your previous performance experiences?

-

3. What experience/training, if any, have you had working with children with additional needs?

-

4. What experience/training, if any, have you had with early language, literacy, and communication development?

-

5. What were your personal expectations of being involved in the sensory storytelling and rhyme sessions program?

-

6. In what ways were you involved in the development of this program?

-

7. Before the program started, how well did you know the children and their sensitivities to sensory input, movement, wait time, etc?

-

8. What forms of communication other than speech do you use that may support children during storytelling and rhyme sessions?

-

9. What professional support do you receive in regard to catering for communication needs of these children?

-

10. What are you aiming to achieve with each performance and the program as a whole?

-

11. How do you measure whether your performances are successful in achieving these goals?

-

12. What do you feel are the expectations of the organisations that you work with in respect to the outcomes for the children?

-

13. What do you think the children gained from the storytelling and rhyme sessions?

-

14. In what ways do you think this program engaged or challenged the children?

-

15. What do you think the parents gained from the sensory storytelling and rhyme sessions?

-

16. Was there anything unexpected from the experience? If so, what was it? Can you explain?

-

17. Is there anything that you think you would change or would do differently given your experiences?

-

18. Is there anything else you would like to share about this experience?

Appendix B

Parent/Carer Guiding Questions

-

1. Can you tell me your reasons for choosing to allow your child to take part in these sensory storytelling and rhyme sessions?

-

2. What were your expectations of the sensory storytelling and rhyme sessions?

-

3. What were you hoping your child would gain from the experience?

-

4. Have the sensory storytelling and rhyme sessions met, not met, or surpassed your expectations? Can you explain your response?

-

5. What do you think your child gained from the sensory storytelling and rhyme sessions?

-

6. What did you (as parent/carer) gain from the sensory storytelling and rhyme sessions?

-

7. Did this program engage your child? Can you explain in what ways?

-

8. Was there anything unexpected from the experience? If so, what was it? Can you explain?

-

9. Is there anything you saw in the sensory storytelling and rhyme sessions that you would be able to use with your child at home?

-

10. Do you think your child’s interest in rhymes/books/words has changed during this program? If yes, what have you noticed?

-

11. Have you experienced any other ‘story time’ programs for young children? If yes, how does this program compare?

-

12. Is there anything else you would like to share about this experience?