China's assertive foreign policy in the last few years under the lead of President Xi Jinping 习近平 has prompted new debates over its rise. Discussions about China's growing global engagement focus on the country's military expansion abroad and its emergence as a global security actor.Footnote 1 While in the past China lacked the resources and confidence to broker security beyond Asia, it is now ready to expand its military power.Footnote 2 Among the regions where the People's Republic of China (PRC) has increased its security and military presence, Africa occupies a prime position. Alongside the PRC's more traditional engagement in trade and infrastructure building, peace and security, which once played marginal roles, now feature prominently in the policy agenda. Since 2011, when China evacuated thousands of its workers from Libya amid civil war, Beijing has paid more attention to issues related to Africa's security environment, and this has been reflected in growing funding of a range of activities including in-kind and financial contributions to the African Union (AU), greater participation in United Nations (UN) peacekeeping missions, and the provision of military training and arms.

This shift in China's approach to African security reflects the broader shift in the country's foreign policy globally. Yet this shift is not mirrored by changes in its official Africa discourse, which continues to emphasize mutual benefits and a common path towards economic growth. This begs the question of how Chinese leaders continued to maintain the continuity of the China–Africa discourse while gradually making space for increased engagement in peace and security. In addressing this puzzle, this article starts from the premise that the success of China's interactions with most countries across the continent is owing not only to attractive economic incentives but also to the coherent official discourse which articulates China and African countries as fellow members of the Global South, united in the struggle against Western hegemony. Investments are indeed important, but they alone cannot explain the breadth of China's engagement. The continent is far from short of investors.Footnote 3 Rather, in China, Africa has found a new partner offering alternative opportunities. Against this background, the article contends that it is by creating the image of a reliable partner and cultivating personal relations with African leaders that China's overall success in the continent can be explained beyond material drivers.Footnote 4

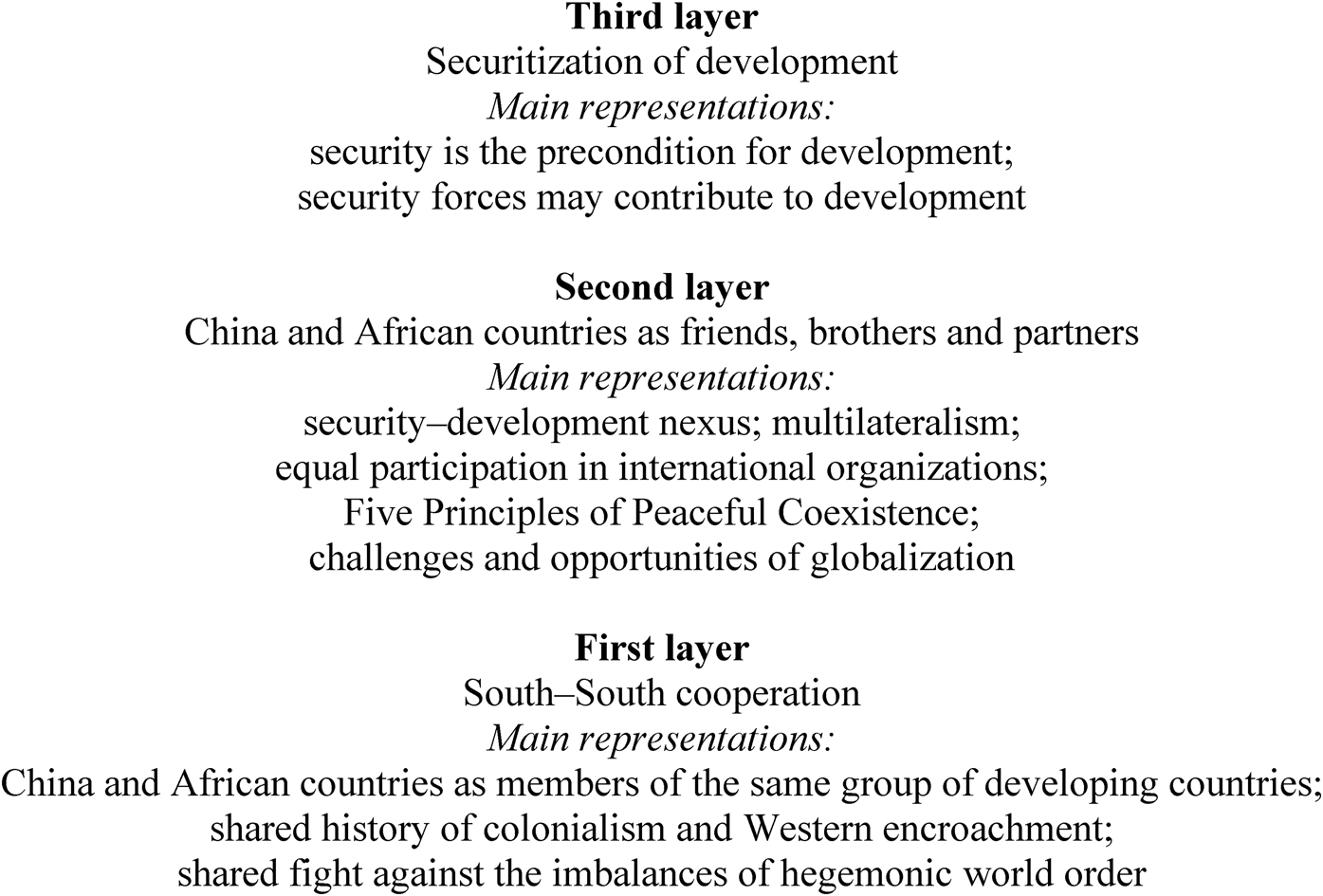

The image of China as a friend and partner has been conveyed through an official discourse that creates a sense of belonging and “common destiny” for leaders in developing countries. Created in 2000, the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) has greatly contributed to building the idea of a shared community and is a good example of China's efforts to create Chinese-led institutions with the objective of increasing its influence abroad. Utilizing Lene Hansen and Ole Wæver's concept of layered discourse,Footnote 5 the article shows that while the country's foreign policy towards the continent has geared towards greater engagement in peace and security, this shift has not been accompanied by changes in the basic discourse (first layer); rather, leaders have built on existing discursive representations and have added more narratives (in the second and third layers). It is mostly thanks to China's use of the security–development nexus as a key discursive representation that the country has been able to maintain a coherent discourse, despite the ebbs and flows in Sino-African relations, while introducing the novel security element. Since the concept entails a close link between the promotion of economic growth and social development and the achievement of stability, growing security and military commitments appear legitimate and reasonable to both China and African countries. The generally positive reception the discourse has found among African leaders enhances its endurance.

This article contributes to the existing literature on Sino-African relations in four ways. First, it addresses Chris Alden and Daniel Large's concern that “despite the vast amount of research produced in recent years on China-Africa relations, the work has remained largely under-theorised and fragmented.”Footnote 6 The article takes up this challenge by proposing a theoretically grounded study of China's Africa discourse that goes beyond the “events of the day” normally driving existing research on the topic.Footnote 7 Second, in joining a number of scholars who similarly see the value in adopting discourse (or rhetorics) as the main object of analysis,Footnote 8 it proposes a more accurate methodological toolbox to interpret China's foreign policy as a “discursively enacted normative ideal,” adding to predominant analyses focusing on material and economic factors.Footnote 9 Third, it builds on the increasingly rich debate over China's growing engagement in African security by focusing not on what China is doing but on how it is doing it.Footnote 10 Fourth, it places the FOCAC at the centre of China–Africa relations and highlights its role both as the primary locus for defining the discourse and practice of China's Africa policies and diplomacy, and as an exclusive China–Africa platform allowing for their relations to develop outside of the West.Footnote 11

The article thus proposes a study of China's Africa discourse and its main representations, as well as their persistency through time, and explains how Chinese leaders have gradually introduced increased engagement in peace and security. Since states are verbal entities that communicate widely, both domestically and internationally, foreign policy discourses are identified through the reading of texts.Footnote 12 Because the relationship between discourse and politics is co-constitutive, not only does discourse hold power over politicians and policymakers but the latter can shape the discourse and use it to justify their preferred policies. As Hansen notes, states may not always follow the policy they publicly declare, and the process of foreign-policy making happens both in public and in private. However, the assumption behind discourse analysis is that “representations and policy are mutually constitutive and discursively linked.”Footnote 13 Therefore, when investigating the linguistic aspects of foreign policy, one must begin with descriptions of such policy through the language of state officials – i.e. statements in which decision makers explain foreign policy goals and which are typically found in speeches, government or semi-government publications, and official meetings. These statements, together with those made by members of the state apparatuses and those appearing in the media, are important as they provide clues to the content of official foreign policy.Footnote 14

Following Hansen's research methodology, the article focuses “on political leaders with official authority to sanction the foreign policies pursued as well as those with central roles in executing these policies, for instance high-ranked military staff, senior civil servants (including diplomats and mediators), and heads of international institutions.”Footnote 15 In particular, the texts were selected based on three criteria, namely that “they are characterized by the clear articulation of identities and policies; they are widely read and attended to; and they have the formal authority to define a political position.”Footnote 16 I collected and read over 250 FOCAC documents including action plans, declarations and speeches given by Chinese and African leaders and top officials (in both English and Chinese), and China's Africa White Papers, from the period 2000 to 2019. I also collected official statements and coverage in state-sponsored media. The texts were sourced from the FOCAC official website, the Central People's Government of the PRC website, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, and official state media such as Xinhua and People's Daily. I read all documents in Chinese and translated the excerpts cited in this article, which are the most exemplary and significant. While reading the texts, I dissected the official Chinese policy discourse, focusing on China–Africa relations and, more specifically, on security cooperation. The article further draws on fieldwork interviews conducted in Beijing, Addis Ababa and New York in the period 2016 to 2018. These interviews granted me more direct access to sources close to foreign policy processes and provided a window through which to look at the reception of China's discourse among African elites.

Through the analysis, a number of elements emerge, including a focus on the security–development nexus; continued assistance for developing countries in promoting development as well as increased militarization and securitization of foreign relations; and the promotion of certain norms and practices, such as the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, via both existing organizations and new institutional arenas. In terms of China's peace and security strategy in Africa, a long-term vision takes shape which includes a bigger commitment to peacekeeping operations, financial and in-kind contributions to the UN and the AU, and a growing military footprint. It is thus important to analyse the discursive basis upon which the PRC's Africa policies rest as well as the changes and continuities in the official discourse in order to understand the future direction of China–Africa policies.

The article proceeds as follows. First, it shows how official discourse is constitutive of Sino-African relations. It then illustrates the discursive layers that form the basis of the discourse. It continues by mapping the discourse's main representations as well as the persistence of these representations since 2000. The fourth section unpacks how the discourse has gradually made space for a shift in China's approach to include more peace and security activities, although no major change in the basic discourse is detectable. Fifth, it shows that the discourse has found broad acceptance among African elites, which contributes to the discourse's endurance. Finally, it concludes with a reflection on the future of China's Africa discourse and policy.

Discourse as Constitutive of the China–Africa (Official) Story

Drawing on Michel Foucault's work, discourse is described by Kevin Dunn and Iver Neumann as “a system producing a set of statements and practices that, by entering into institutions and appearing like normal, constructs the reality of its subjects and maintains a certain degree of regularity in a set of social relations. Or, more succinctly, discourses are systems of meaning-production that fix meaning, however temporarily, and enable actors to make sense of the world and to act within it.”Footnote 17 Within a discourse, representations construct regimes of truth or knowledge; they not only constitute identities but also foreign policies and their outcomes.Footnote 18 Representations are phenomena filtered through the existing fabric between the world and ourselves.Footnote 19 In this context, discourse is able to show how certain representations are constituted and prevail over time, since within specific discourses, certain paths of action become possible while others are made more unlikely or even unthinkable.Footnote 20 While discursive representations precondition foreign policy, they are also “(re)produced through articulations of policy.”Footnote 21 Or, as Wæver puts it, making debates and actions of a certain country more intelligible to other observers is made easier by presenting patterns of thought in a systematic way.Footnote 22 Therefore, a study of discourse implies the study of both language and practices. As defined by Barry Barnes, practices are “socially recognized forms of activity, done on the basis of what members learn from others.”Footnote 23 In other words, while discourse refers to preconditions for action, practices are socialized patterns of action, and “as long as people act in accordance with established practices, they confirm a given discourse.”Footnote 24

Other scholars have developed an interest in studying the apparent continuity of the political rhetoric on China–Africa relations. For instance, Bjørnar Sverdrup-Thygeson suggests that narratives recalling historical links between the Middle Kingdom and African countries are especially important tools in China's foreign policy.Footnote 25 Narratives, which are among the possible modes of discourse arranging information in a logical order, can be defined as “linguistically mediated temporal syntheses”Footnote 26 which do not simply list events but rather order them in a story.Footnote 27 Julia Strauss uses the concept of rhetoric (and subsequently layered rhetorics) to navigate through the changes and continuities of Chinese official and semi-official texts.Footnote 28 She suggests that these are based on a set of logical supporting ideas underlining a developmental model that is thought to be both different from and better than the West. The consistency of such rhetoric makes it possible for China to make credible claims to be Africa's friend.Footnote 29 She further maintains that it is unlikely for the rhetoric, which includes amity, equality, win-win, common development and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), to change substantially in the future.Footnote 30 Adding to these arguments, this article argues that if one wants to identify the reasons for the persistence (or not) of certain linguistic representations in China's Africa discourse, one must go deeper and uncover the different discursive layers that structure Sino-African relations. In particular, since rhetoric is an art of discourse, it does not exist prior to discourse.Footnote 31 The current article builds on these studies by proposing a theoretically grounded and methodologically accurate analysis of China's Africa discourse and how it has adapted to changes in both the international environment and the specificity of China–Africa ties, and focuses on peace and security and the security–development nexus to illustrate this.

The Layered Discourse

As this article seeks to unearth China's Africa discourse, how it has gradually included peace and security and how it has contributed to creating an image of China as a reliable partner, discourse analysis is applied to identify the dominant representations of China–Africa – what Dunn and Neumann call an “inventory of representations.”Footnote 32 In this sense, Chinese politics presents researchers with unique challenges. China's official discourse is imbued with a language that, according to Gloria Davies, “reflects not only the constraints of prolonged, ongoing state censorship but also a poetics of anxiety constitutive of the very discourse that seeks to articulate it.”Footnote 33 However, as William Callahan contends, while “[o]fficial Chinese discourse is often very vague, repetitious and unwieldy,” official slogans are “crucial in organizing thought and action in Chinese politics.”Footnote 34 Looking for repetitions of representations is especially useful to construct such an inventory of representations.Footnote 35 The current article uses the concept of layered discourse, which can “specify change within continuity” by referring to “degrees of sedimentation: the deeper structures are more solidly sedimented and more difficult to politicize and change.”Footnote 36 Each layer of the structure adds specificity as well as constraints to the analysis. According to this understanding of discourse, scholars are able to make contingent “predictions” and establish, for instance, that when the discursive system is under pressure, it may happen that several policies are presented as possible; while these may be very different from each other at the surface level, they are all logically possible constructions on the basis of the basic discursive elements available to policymakers. Change is always possible, at least in principle, given that these structures are socially constituted. The post-2011 refocusing of China's policy towards African security thus did not represent a rupture producing a radically new agenda “where several basic premises have changed.” Rather, it was a variation on the basic premise of the deeper discursive layers.Footnote 37

Drawing from Dunn and Neumann, the discourse analytical process used in this article to uncover China's Africa discourse follows several steps. The first is mapping the main representations as they appear in official policy documents, as well as their persistence.Footnote 38 This is done by reading texts from the FOCAC, which provides an ideal space for China to promote its discourse. The approach focuses on “the identity of linguistic signs and tropes or the persistence of particular metaphorical schema” seeking to uncover an organizing principle within a given discourse.Footnote 39 In particular, this article is concerned with the continuity and longevity of representations of China as a fellow member of the Global South and as a developing country; of China and Africa as friends, brothers and partners; and of China and Africa as united in the struggle against the imbalances of a system dominated by the developed North. A discourse analyst should also be able to demonstrate change within continuity.Footnote 40 Thus, starting from the basic discourse representing China and Africa as fellow members of the Global South and progressively focusing on peace and security, it becomes clear that the security–development nexus has been a constant feature of official rhetoric but that the securitization of development only becomes prominent from 2011. The second step is layering the discourse, namely demonstrating how the identified representations differ in historical depth, in variation and in the degree of their dominance or marginalization in the discourse.Footnote 41 How was it possible for Chinese leaders to incorporate increased engagement with peace and security while the issue had been marginal until then? Is such a shift in policies reflected by a change in the narratives utilized? The article suggests that in order to legitimize China's new security and military presence in the continent, leaders in Beijing have built on the existing discursive representations. The third step is tracing the development of the discourse through time. This is done by comparing official documents and speeches in the period 2000–2019 to track changes in the narratives used to sustain the discourse.

As noted by Wæver, while there is a certain creative element in drawing the layered structure in different cases and its contents cannot be discovered by a formalized method, “this discourse analysis has a synchronous and diachronous part … The first establishes a model by fitting together material from different contexts, actors and years into a structure, while the second moves through time with specified actors and studies how the structure shapes and how it is reproduced and modified.”Footnote 42 Therefore, in the first part of the discourse analysis, one creates a logic by finding powerful examples from different contexts that highlight a clear pattern; in the second, one focuses on context and interaction, for instance on how actors draw on the discursive structures or resist them. The structure created in the synchronous part of the analysis serves as an analytical instrument to follow the political process and actors in the diachronous part of the analysis. Based on this approach, I trace the foundational discourse at the root of China's Africa policy, analysing its development in FOCAC documents over the last two decades, and establish how it frames contemporary policies. I identify the more specific representations of China and Africa as friends, brothers and partners, as derived from the basic “South–South cooperation” narrative. I then track the change that led to the post-2011 increased securitization of development within the existing discourse and link that to China's security policies in the continent.

Figure 1 illustrates how China's Africa discourse unfolds. In the first layer, the discourse provides “an analytical perspective that facilitates a structured analysis of how discourses are formed and engage each other within a foreign policy debate” and offers an ideal type of the China–Africa partnership.Footnote 43 This first layer can be called the “South–South cooperation” discourse. It consists of the basic representation of China and African states as members of the same group of developing countries and also positions China within the group. This basic discourse, whereby China and Africa share a history of colonialism and Western encroachment and are united in the fight against the imbalances of an unjust world system, provides a series of possibilities and constraints in terms of how foreign policy may be presented, what kind of foreign policy options may be pursued, and how China–Africa relations may be (re)defined. The second discursive layer comprises a number of representations that are informed by the “South–South cooperation” logic: globalization is both a challenge to overcome together and an opportunity to be seized by China and Africa; they share a commitment to multilateralism and equal participation in international organizations; they abide by the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence; and their leaders believe that the security–development nexus is an essential policy tenet. The article specifically argues that the nexus not only provides a useful framework through which to understand China's security practices in Africa, as Lina Benabdallah suggests, but it also plays a crucial role in underlying China's Africa discourse: by understanding peace, security and development as fundamental and interconnected features of a desirable political environment, it links stability to economic growth.Footnote 44 This entails that the inequality of the current international system represents a threat to the development and the security of countries in the Global South; hence, both development and security need to be pursued in order to achieve a more equal world order. The third discursive layer adds further specificity to the abstraction of the second layer by presenting more specific policies. This is where a certain degree of change is allowed. While China's focus until 2011 was on the developmentalization of security, premised on the belief that economic growth leads to stability, after 2011 the discourse begins to include a more pronounced securitization of development, whereby economic prosperity and social development can only be achieved in a peaceful and stable environment. Simultaneously, no changes are detectable in the first and second discursive layers.

Figure 1: The Layered Structure of China's Africa Discourse

The Discursive Representations of China–Africa Relations

This section maps the main representations that constitute China's Africa discourse and which have remained stable despite Sino-African relations evolving constantly. It explores the construction of the security–development nexus within the existing discourse in an attempt to unpack how the latter has made space for a change in China's approach to peace and security in the continent. From reading official texts, it becomes clear that China has moved from a policy of non-intervention and non-involvement to considerable engagement in a variety of security-related activities. While such change is detectable in the third discursive layer, the first and second discursive layers that sustain China's Africa policies have remained the same.

As mentioned above, the basic official discourse constructs China and Africa as fellow members of the Global South and defines their relations in terms of “South–South cooperation.” The South forms the source of an identity for both state and non-state actors which encapsulates the common experience of colonialism and imperialism. It is used as a mobilizing strategy based on a critique of the asymmetries and inequalities of the contemporary international system, thus calling for change to the current structures of global governance.Footnote 45 On this basis, different representations define China–Africa relations, such as a shared experience with colonialism and Western encroachment and unity in fighting a hegemonic world order. Despite relations fluctuating, this basic discourse has remained stable and coherent. Arguably, the narratives that support it have not remained entirely unchanged; at times, some have been dropped and new ones introduced to chime with changes in the relationship.Footnote 46 However, it is possible to identify the representations that have contributed to articulating a stable and coherent discourse.

The basic “South–South cooperation” discourse pivots on the belief that the current world system is unjust and rooted in the economic, scientific and technological gap between the North and the South. In 2003, the-then premier Wen Jiabao 温家宝 declared that “the gap between North and South has continued to widen … [and] has intensified, and the task of maintaining economic security and achieving sustainable development in developing countries, especially in Africa, has become more arduous.”Footnote 47 According to China's leaders, the gap is a sign that “hegemony and power politics still exist. The task of safeguarding the sovereignty, security and interests of developing countries remains daunting.”Footnote 48 Hegemony is encapsulated in the control developed countries hold over global affairs and their exploitation of natural resources in developing countries.Footnote 49 In turn, “owing to long-term poverty and backwardness, coupled with the influence of various external factors, potential ethnic, religious and social contradictions have been intensified, conflicts and wars have continued to appear, and the stability and development of some developing countries have been seriously damaged.”Footnote 50 China therefore proposes to create a new world order: “As mankind is about to enter the new century, the establishment of a fair and reasonable new international political and economic order has become a requirement of changing times and the common voice of people all over the world. Let us … work together to promote the establishment of this new order and the noble cause of peace and development of mankind.”Footnote 51 Chinese leaders are careful to clarify that China does not intend to pursue a revisionist foreign policy or subvert the existing system. Rather,

The Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations, and the principles and spirit of the Organization of African Unity Charter and other universally recognized norms of international law should form the political basis of the new international order. On the premise of consensus among peoples, new principles reflecting the spirit of the times should also be established in the context of the development and changes of the world.Footnote 52

Based on this, more specific representations emerge in the second layer. China and African countries are pictured as friends, brothers and partners. While the first layer already implies friendship and partnership, this representation acquires further nuances in the second layer, as the friendship is symbolized by multilateral engagement and equal participation in international organizations. In the first FOCAC Declaration, Chinese and African delegates argue that given the “steady development of China–Africa relations over the past decades,” they are confident “in the prospects for cooperation” and believe that “the China–Africa traditional friendship has a long history and a solid foundation of friendly cooperation … [that] China and Africa belong to the group of developing countries and share fundamental interests, and … China and Africa's close consultation in international affairs is of great significance for consolidating solidarity among developing countries and further promoting the establishment of a new international order.”Footnote 53 In 2006, the-then president Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 gave the following address to the participants of the Third FOCAC:

Although China and Africa are far from each other, the friendship between the people of China and Africa has a long history and it becomes stronger with time. Throughout this long history, the people of China and Africa have been striving for self-improvement and perseverance and have created distinctive and colourful ancient civilizations. In modern times, the people of China and Africa have been unwilling to be enslaved and have fought stubbornly. They have written a glorious chapter in the pursuit of freedom and liberation and safeguarding human dignity, creating a glorious history of nation-building and national rejuvenation.Footnote 54

The assumption here is that the China–Africa friendship is a long-lasting one, dating back to the early Ming dynasty.Footnote 55 To be sure, this depiction of events hardly represents the historical reality of China–Africa ties, which is all but continuous. For instance, Zheng He's 鄭和 expeditions may not have been as peaceful as Beijing likes to portray them.Footnote 56 And China–Africa relations ceased after those early encounters, resuming only in their modern form during the Mao era.Footnote 57 Despite inaccuracies, the narrative serves the diplomatic purpose of depicting China and Africa as sharing a long friendship. At the 2018 FOCAC, Xi Jinping described China and Africa as being “family” in his inaugural speech and lauded their partnership for its authenticity and strength:

China insists on sincere friendship and equal treatment in cooperation … always respecting Africa, loving Africa, supporting Africa, and insisting on achieving the “five nos”: not interfering with African countries in exploring development paths that suit their national conditions, not interfering in African internal affairs, not imposing one's will on others, not attaching any political conditions to aid, and not seeking private political gains in investment and financing in Africa. … China will always be a good friend, partner and brother of Africa.Footnote 58

The challenge and opportunity of globalization form another important discursive representation. The challenge discourse remained largely constant throughout the first three FOCAC meetings and was then afterwards accompanied by concerns over the global financial crisis.Footnote 59 The implication is that developed countries, which have shaped the current world order according to their norms and interests, are benefiting from globalization while developing countries are left with a series of difficult tasks. This is said to require an even stronger China–Africa cooperation. Furthermore, “despite the difficulties encountered by China's economic development as a result of the international financial crisis, China is committed to continuing the expansion of its assistance to Africa.”Footnote 60 Both representations equally legitimize increasing economic contributions to the continent, with China portraying itself as an ally willing to continue, and even scale up, its financial commitments to ensure economic growth for the continent.Footnote 61 Globalization was then presented as an opportunity that developing countries need to seize as Chinese leaders came to accept that global economic integration could have a positive impact on economic development.Footnote 62 The 2018 Declaration calls upon the international community to “work together to promote development through trade and investment, and to promote economic globalization towards a more open, inclusive, balanced, and win-win direction.”Footnote 63 The opportunity representation calls for greater inclusion of African countries in the UN Security Council (UNSC) and increased support for the UN as well as other multilateral organizations. Chinese leaders often stress the central role of the UN in promoting multilateralism and “democracy” in international affairs.Footnote 64 The 2018 FOCAC Declaration states that China and Africa adhere “to the global governance concept of extensive consultation, joint contribution and shared benefits” and advocate multilateralism and “the democratization of international relations, insisting that all countries, big or small, strong or weak, rich and poor, are equal.”Footnote 65 The Chinese understanding of “democratization” here refers to equal participation in decisions taken at international organizations. In this vein, an undemocratic system is one which precludes (certain) developing countries from actively participating in international decision-making processes. China, its leaders argue, intends to use its position as a permanent member of the UNSC to advocate for developing countries’ further inclusion.

Finally, the principles of non-interference and respect for state sovereignty are ever present in China's Africa discourse. China's stance is that is supports “the leading role of African countries and regional organizations in resolving regional issues … [and] their efforts to independently resolve regional conflicts, strengthen democracy and building good governance, and oppose external forces interfering in African internal affairs out of their own interests.”Footnote 66 Additionally, “as an important norm in international relations, the principle of non-interference in internal affairs is not out of date. Especially for developing countries, the principle … is still an important guarantee for safeguarding their own rights and interests.”Footnote 67 Indeed, the question of China's position on non-interference often crops up in China–Africa debates. China's support of mediation efforts in Sudan, its alleged role in some countries’ change of leadership, and its growing contributions to the continent as a whole put these principles increasingly under strain.Footnote 68 The next section aims to address the question of how peace and security policies as well as China's increasing involvement in security and military activities in the continent fit into the basic discourse.

Legitimizing the Securitization of Development through the Security–Development Nexus

The basic discourse and the main representations employed by Chinese decision-makers when constructing China–Africa relations within the “South–South cooperation” framework legitimize policies directed at promoting development and economic growth in Africa as a priority. Within this framework, security occupies an important place; however, the extent to which it has been a part of China's Africa policy has changed throughout the years. While mentions of peace and security as one element of the China–Africa partnership are detectable from 2000, the first two FOCAC meetings only make vague and general references to the topic. Security issues gradually became more prominent as China participated in mediation efforts in Sudan.Footnote 69 But it is from 2011 that China's position on security matters began to be clearly articulated. These developments coincide with the start of Xi Jinping's term and his emphasis on military modernization.Footnote 70 The shift also responds to the need to protect Chinese citizens and interests abroad and a more general interest in contributing to international peace and security.Footnote 71 It also follows a broader trend on the African side, where the political focus has moved from economic integration to security, and demands for China's engagement have increased.Footnote 72

The understanding of peace and security that emerges from FOCAC documents is rooted in China's domestic practices, where security is intimately connected to development: reducing poverty and improving living conditions are considered key elements for achieving peace and stability.Footnote 73 In the Western context, the security–development nexus is a familiar representation which has long been at the centre of the “liberal peace.” According to Mark Duffield, it links development and security in the sense that “insofar as development is able, for example, to reduce poverty, improve well-being or generate hope, it is also felt to have a concomitant potential to promote local and international security.”Footnote 74 In China, the nexus refers to how development can promote the stability of the regime first and foremost. As Benabdallah contends, “China's own history with political interference in economic development … has resulted in a strong belief in the necessity of economic growth to maintaining internal order,” so that the governing elites are free from violent challenges to their rule.Footnote 75 Furthermore, the focus of the Western approach is on democracy and human rights, whereas the “Chinese peace” privileges sovereignty and the legitimacy of the government.Footnote 76 While “liberal peace” and “Chinese peace” are not equal in terms of conceptual development or practice on the ground, the latter is not opposed to the assumption that democracies are more peaceful over time.Footnote 77 For the purpose of this article, it should be noted that China intentionally brands its approach as different from that of Western powers.Footnote 78 This has helped to make China's peacekeeping and peacebuilding efforts more attractive to African leaders wary of foreign interference. Despite this distinction, establishing the nexus as a representation in China's Africa discourse was possible also because the link between security and development existed in familiar discourses and policies already. As Xi Jinping argued in 2014, “sustainability means paying equal attention to development and security … Development is the foundation of security, and security is the precondition for development. A tree of peace cannot grow on a barren land, and no fruits of development can be produced in the flames of war.”Footnote 79

In 2014, Premier Li Keqiang 李克强 insisted that “[w]ithout a peaceful and stable environment, development will not be possible.”Footnote 80 A joint statement by Chinese and African ministries issued in 2013 announced that “the relationship between peace, security, stability and development should be handled in a balanced manner to resolve the root causes of conflicts. Comprehensive measures should be taken to address hotspot issues and their symptoms and root causes, and we should continue to pursue dialogue and consultations to resolve regional disputes.”Footnote 81 The nexus is therefore key to understanding the successful legitimization of increased security practices within the existing discourse. It frames peace, security and development as fundamental and interconnected features of a desirable political environment. Since the inequality of the current world order represents a threat to both the development potential and the stability of the Global South, both development and security should be pursued in order to achieve a more equal international system. In other words, the nexus creates a sort of quasi-causal argument, which provides “warranting conditions” making a certain action or belief more reasonable, justified or appropriate, given the beliefs and expectations of those involved.Footnote 82 In this case, given that security can be achieved through development, it is considered acceptable that China provides economic aid to African countries in order to simultaneously promote stability. Crucially, the nexus is considered appropriate by African leaders, who generally welcome the Chinese approach. The discourse, then, legitimizes developmental, infrastructure and logistics-related policies in light of the pursuit of peace and security.

At the same time, security issues have gained more prominence in China's Africa policy. Both Chinese and African leaders seem to agree that “security forces can, and should on occasion, contribute directly or indirectly to development.”Footnote 83 The third discursive layer thus adds further specificity to the abstraction of the second layer and results in more specific policies including increased participation in peacekeeping missions and an expanded Chinese military footprint on the continent. While China's policy focus until 2011 was on the developmentalization of security, premised on the belief that economic growth leads to stability, since 2011 Beijing has embraced a change towards a more pronounced securitization of development, whereby economic prosperity and social development are only achievable in a peaceful and safe environment. Furthermore, aware of the tension between respect for state sovereignty and increased participation in security activities, Chinese scholars are at work to conceptually redefine foreign policy pillars such as respect for state sovereignty and non-interference, with the aim to “keep them intact but adapt them retroactively.”Footnote 84 Operating under the banner of the UN further helps China to resolve this tension, as UN resolutions give legitimacy to interventions.Footnote 85 Thus, the patterns of Chinese engagement and the discourse in the third discursive layer have changed, without being accompanied by changes in the first or second discursive layers.

For instance, the Declaration following the Fifth FOCAC maintains that Chinese leaders are “deeply disturbed by the current turmoil in some regions and reaffirm that we should jointly uphold the principles of the UN Charter and the basic norms of international relations, advocate the peaceful settlement of crises and disputes through political means, and advocate a security concept of mutual trust, mutual benefit, equality and cooperation.” Further, they commit to “strengthen bilateral exchanges and cooperation, promote the operationalization of the African peace and security architecture, and continue to support and assist African countries in increasing their capability for maintaining peace and security, as well as enhance coordination and communication in the UNSC and other multilateral institutions.”Footnote 86 In 2012, Beijing pledged 600 million yuan in aid and other measures to strengthen the practical cooperation between China and the AU.Footnote 87 Furthermore, during the Sixth FOCAC meeting, Xi Jinping committed US$60 million in free military assistance over the following three years.Footnote 88 In his speech during the Seventh FOCAC, Xi linked China–Africa security cooperation to China's “new security concept.”Footnote 89 He proposed to:

Join hands to build a China–Africa community with a shared safe future … China advocates a common, comprehensive, cooperative, and sustainable new security concept, firmly supports African countries and regional organizations such as the AU to solve African problems in an African way … China is ready to play a constructive role in promoting peace and stability in Africa and support African countries in enhancing their capacity to independently maintain peace and stability.Footnote 90

He also committed US$100 million in support of the African Standby Force and the African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crisis and announced 50 security assistance programmes to advance cooperation in the areas of law and order, UN peacekeeping missions and fighting piracy and terrorism.Footnote 91 Peace and security feature as one of the eight initiatives that will inform discussions at future meetings. During the China–Africa Peace and Security Forum meeting in 2019, China argued that “security in Africa is a barometer of the global security governance system” and that “for developing countries, development concerns security and holds the master key to solving security issues.”Footnote 92

The above analysis of China's Africa discourse across its three constitutive layers shows how engagement with peace and security, once marginal in Sino-African relations, has become central. Legitimizing increased participation in the continent's peace and security architecture was possible thanks to the persistence of China's official discourse. In particular, the security–development nexus plays a crucial role in justifying policies that envision greater participation in peacekeeping missions, an expanded military presence in the continent, and greater financial and in-kind contributions to the AU. The following section discusses how this approach has been mostly welcomed by African leaders.

Accepting China's Discourse

The endurance of China's image as a friend to African countries does not only depend on Beijing's successful articulation of such an identity when addressing African audiences. China's discourse is generally welcomed by African leaders because it positions the China–Africa friendship as joined in opposition to colonialist practices.Footnote 93 This section draws on fieldwork interviews to illuminate these perceptions. Generally, African decision makers identify with China's discursive representation as belonging to the same group of developing countries, and the Chinese leadership seems to believe that African elites seek to emulate the PRC's path to modernization.Footnote 94 China's economic transformation is admired by the continent's elites, who view it as a possible model to emulate and achieve domestic development.Footnote 95 Specifically, some interviewees argued that requests in the late 1990s to create the FOCAC came from African leaders who felt the moment was ripe to institutionalize bilateral relations with China.Footnote 96 The PRC's emphasis on stability rather than regime change, and the relatively few conditions attached to China's assistance, made engagement with China very appealing.Footnote 97 China's growing involvement in peace and security has also largely been welcomed because its approach is seen as “descriptive,” in contrast to the more “prescriptive” Western approach.Footnote 98 Some interviewees emphasized the agency of African actors in negotiating with China, pointing out, for instance, that decisions on how to spend any Chinese funding to the AU rest solely with AU staff, thereby underlining the independent decision-making process of the organization.Footnote 99 African leaders seem to appreciate China's contributions to UN peacekeeping missions, especially in terms of personnel.Footnote 100 Establishing close relationships with African leaders and links with government officials is a key objective of China's foreign policy in Africa.Footnote 101 China cultivates relations with Africans through, among other things, scholarships, high-level official visits and capacity-building programmes in a range of fields, all of which add to the attractiveness of Chinese engagement.Footnote 102

This article does not suggest that China's Africa policies are solely motivated by generosity or that economic incentives play only a marginal role. On the contrary, the shift away from a strict understanding of non-interference reflects the realization that security is a prerequisite for investments.Footnote 103 Furthermore, less positive views of China's involvement can also be found. For instance, one African interviewee described how Chinese officials exhibited a sense of superiority, what he called “Middle Kingdom syndrome.”Footnote 104 One downside of China's descriptive approach is that it allows those African leaders who are not interested in the human rights of their citizens to take advantage and continue to operate within their countries as they wish.Footnote 105 Regarding security issues, some interviewees related that China's perceived lack of exposure to and understanding of African conflicts and their ethnic and religious roots makes it harder to achieve concrete results.Footnote 106 Others commented that when contributing to peace operations, China rarely goes beyond financial contributions, and does not normally offer the policy advice that some European countries do.Footnote 107

The overall positive reception of the official discourse by African elites has in turn contributed to what are viewed as mutually beneficial and equal relations, although these remain asymmetrical in economic nature. By constructing China's identity as a fellow benevolent country, Chinese leaders establish their interests; by accepting such a narrative, African leaders find themselves comfortable with their identity as partners in a shared community, and they, too, can pursue their own agendas.

Conclusion: Looking Ahead

This article analyses China's official Africa discourse to account for the role it plays in maintaining continuity throughout shifts in policy. The discourse, premised on “South–South cooperation,” positions China and Africa as long-term friends and partners and has remained relatively stable over the last two decades owing to a series of historical and political narratives which aim to create a sense of belonging and a “common destiny.” The analysis situates the FOCAC at the centre of China–Africa relations, as an exclusive platform where Chinese leaders promote their approaches and practices and discuss them with their African counterparts. When China geared towards greater engagement in African security after 2011, this shift in foreign policy was not accompanied by radical changes in the basic discourse. Instead, the policy change (third discursive layer) represents a variation of the basic premise of the deeper discursive layers (second and first). Rather than fabricating an entirely new discourse to justify and legitimize the new policy, leaders in Beijing have built on existing discursive representations. The security–development nexus has played a central role in legitimizing the securitization of development in the discourse. Since it entails a close link between the promotion of economic growth and social development and the achievement of stability and peace, growing security and military commitments appear legitimate and reasonable. The overall success of the discourse depends on both the longevity of the main representations and the image of China as a reliable and legitimate partner, combined with the largely positive response they have encountered among African leaders.

The acceptance of China's discourse has generally made it easier for Sino-African relations to absorb the shocks of diplomatic crises, such as the recent mistreatment of Africans in Guangzhou.Footnote 108 Furthermore, China's experience on the ground suggests that the country has so far relied on a pragmatic approach and has learned from past mistakes. The unpreparedness for the Libya uprisings in 2011 was indeed a lesson learned for China and encouraged the move towards growing engagement in African security, alongside demands from the African side. Nonetheless, while the basic discursive layer is considered to be highly resilient, it is not immune to change.Footnote 109 External developments that challenge existing representations or single individuals and institutions that rearticulate basic concepts can exert pressure to change; this typically results in a (discursive) tension that the discourse cannot easily handle.

Conversely, while change is possible and traceable, deviations from or attempts to renegotiate the dominant constellation of representations would likely fail to attract recognition within the policy debate, owing to the solidity of the existing structure of meaning.Footnote 110 Understanding these dynamics makes it possible to make “predictions” on the future of a dominant discourse that seems to be well functioning, or on one that is under significant pressure.Footnote 111 Hence, China–Africa relations could continue unscathed while pragmatically and gradually adapting to evolving circumstances, or they could be substantially renegotiated. On the one hand, the stability of China's discourse and the variables affecting it, including receptivity from the African side and learning through experience on the ground, suggest that a deeper discursive change is unlikely. On the other hand, the current strategic rivalry between China and the US poses a dilemma for countries that may have to pick a side (either on specific issues or on foreign policy in general), thus potentially prompting a clear rupture. While African countries have so far managed to stay out of the confrontation, this may be increasingly difficult in the future, since there will be greater demand for garnering diplomatic support for one's preferred norms and practices. For the time being, there does not seem to be any major pressure on or anomalies in China's Africa discourse. Simultaneously, cracks have opened on the surface of China–Africa relations, mainly owing to an increasingly vocal civil society that is less willing to accept the official story at face value. If there is to be any significant change in the basic discourse, it will likely be prompted by young and motivated netizens who already play a crucial role “in re-designing how China–Africa relations are experienced by people beyond the government elites and the Global South rhetoric” through social media.Footnote 112

Acknowledgements

The several fieldwork trips to Beijing, Shanghai, Addis Ababa and New York were sponsored by the LSE PhD Mobility Bursary; the Global South Doctoral Fieldwork Research Award; and the Dominique Jacquin-Berdal Travel Grant for Fieldwork in Africa. I am thankful to two anonymous reviewers and the editors for their helpful comments. I am also grateful to Bjørnar Sverdrup-Thygeson, Gee Berry and Magnus Langset-Trøan for their feedback and attention to details.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Ilaria CARROZZA is a senior researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), where she currently works on artificial intelligence as a frontier of US–China competition, the ethics of algorithms, dual-use technology, and the security assistance provided to countries in Africa, the Middle East and South-East Asia. Her broader research interests include Chinese foreign policy, China's engagement in Africa and Asia, the Belt and Road Initiative, the Digital Silk Road and South–South cooperation. She was the editor of Millennium: Journal of International Studies, Vol. 45, and has worked as a consultant at the UNESCAP in Bangkok, where she led a project on sustainable development in the Asia-Pacific region.