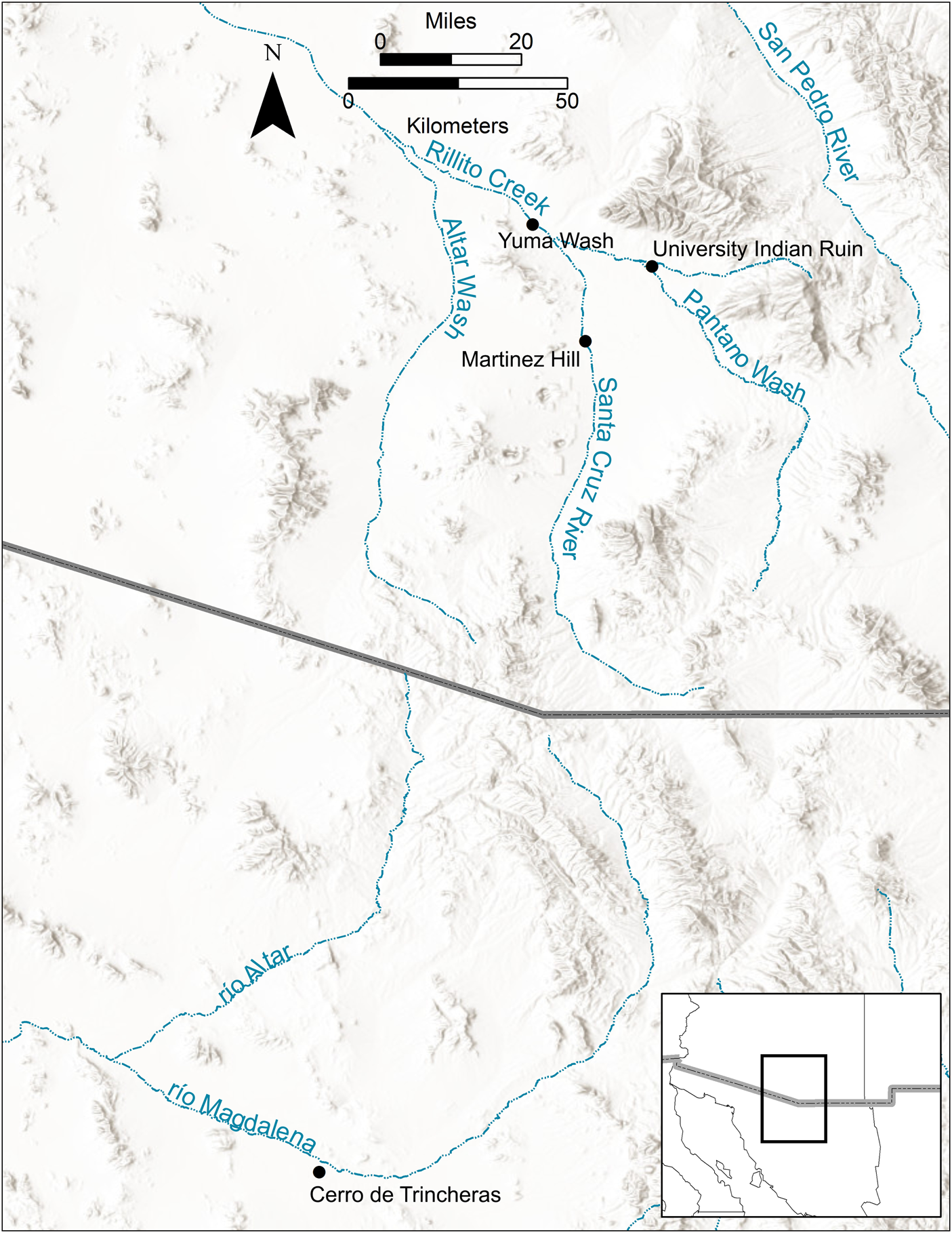

The present research compares mortuary practices among the Tucson Basin Hohokam of southern Arizona during the Classic period (AD 1150–1450) to those of the residents of the Cerro de Trincheras site in northern Sonora, Mexico, which was occupied from approximately AD 1300 to 1450 (Figure 1). In this article, I focus on two main questions:

(1) What does the treatment of the dead tell us about social interactions on a broader regional level between these two regions?

(2) What do cremation funerals tell us about broader aspects of ideologies related to personhood and embodiment?

The connections between the southwest United States and northern Mexico have long been an important research inquiry in archaeology (Haury Reference Haury1945; McGuire Reference McGuire1980; McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011, Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Canchola, Punzo Díaz and Minnis2015). Both the Trincheras and Hohokam traditions of the Sonoran Desert constructed shallow pithouses, made shell jewelry, practiced irrigation agriculture, and cremated their dead (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011). There are also clear differences between them, however. The Trincheras tradition is dissimilar from the Hohokam in its primary methods of ceramic production, artifact assemblages, ritual diversity, and rock art design styles. It also lacks platform mounds and in general has smaller and less-built-up settlements, with the exception of the Cerro de Trincheras site (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011). Although separately the Hohokam and Trincheras traditions had broad social networks across the Greater Southwest, little evidence of social interaction between them has been documented (Braniff Reference Braniff Cornejo1992; Fish and Fish Reference Fish, Fish, Fish, Fish and Elisa Villalpando C.2007; Haury Reference Haury1976; Johnson Reference Johnson1960; McGuire Reference McGuire and Gumerman1991; McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011, Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015). There is even a possibility that Trincheras and Hohokam groups were in conflict with each other (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015).

Figure 1. Trincheras and Tucson Basin archaeological sites discussed in the text. Created by Matthew Pailes.

Despite the amount of research conducted on the two traditions, each region's respective funeral rituals have yet to be systemically compared and contrasted. Mortuary practices offer a way for in-depth exploration of wider and more varied social interactions beyond the spread of technological knowledge, trade and/or economic transactions, and conflict.

Both the Classic period Tucson Basin Hohokam and Cerro de Trincheras populations primarily cremated their dead. Cremation is a complex, multistage process, of which the burning of the body is only one stage. Even though some aspects of the cremation ritual are similar between the two traditions, there are also critical differences, especially regarding the burial itself. Keeping these differences in mind is important when studying the mortuary practices and the archaeology of the prehispanic Greater Southwest.

The Hohokam and Trincheras traditions had some of North America's most diverse and extensive cremation customs, including the use of pyres and postburning rituals. The vast amount of data I examined from well-documented contexts has allowed me to go beyond overly general comparisons of funeral treatments and to present an in-depth, step-by-step comparison of the stages of the mortuary rituals. This approach is also important because it provides a holistic view that takes into consideration the decedent, mourners, community, and use of space.

Embodiment and Personhood

The concept of embodiment emphasizes the diversity of bodies as lived experiences. How a body becomes a subject in social space can be used to explore the relationship between culture and self. Csordas (Reference Csordas, Weiss and Fern1999) notes that embodiment invokes both Merleau-Ponty's (Reference Merleau-Ponty and Smith1962) idea of subject-object (or concept of “perception”) and Bourdieu's concept of “habitus.” In archaeology, interest in the concept of embodiment has become popular (e.g., Crossland Reference Crossland, Hicks and Beaudry2010; Fisher and Loren Reference Fisher and Loren2003; Meskell and Joyce Reference Meskell and Joyce2003). Previously, the body was viewed as stable material on which different identities, such as gender, were inscribed (e.g., Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1999; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2000; Voss Reference Voss2008). Interest in studying lived experiences emerged later (Crossland Reference Crossland, Hicks and Beaudry2010). These studies questioned preconceived ideas about the human body, focusing more on how and which practices and social relationships define bodies (e.g., Crossland Reference Crossland, Hicks and Beaudry2010; Fisher and Loren Reference Fisher and Loren2003; Joyce Reference Joyce1998, Reference Joyce2005; Meskell Reference Meskell1999).

A common focus of inquiry has been on the relationship of body and mind, subject and object, derived from practice theory (Crossland Reference Crossland, Hicks and Beaudry2010), in which embodied subjects are shaped through discursive practices and control of their own society. Meskell (Reference Meskell2000) has criticized approaches derived from practice theory as overemphasizing the “social body,” suggesting that they view past bodies as artifacts without considering them as individuals per se or as specific forms of embodiment. Critiques within archaeology have also questioned the emphasis on individual differences rather than commonalities, artificially isolating individuals from society and providing little recognition of the institutions and structures in which they lived (Sofaer Reference Sofaer2006; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2000). Missing as well from many of these studies are the life histories of individuals (Sofaer Reference Sofaer2006), except for a few instances (e.g., Joyce Reference Joyce2000, Reference Joyce2003).

Derived from a growing interest in both materiality and embodiment, increased attention has also been paid to understanding ideas of personhood or self as situated within, throughout, or without the bounded body (Hallam and Hockey Reference Hallam and Hockey2001; Meskell Reference Meskell1999; Sofaer Reference Sofaer2006). Mauss (Reference Mauss, Carrithers, Collins, Lukes and Halls1985) suggests that the notion of self is something that can change through time and space, as well as due to specific cultural norms. Building on these ideas, anthropologists such as Fortes (Reference Fortes1987) argue that personhood—what constitutes the state or condition of being a person—was also negotiated and relational (see also Brück Reference Brück2006; Chapman Reference Chapman2000; Fowler Reference Fowler2001; Jones Reference Jones2005). Taking these ideas into consideration, personhood can be seen as a social construct that is inherently dynamic and relational, taking on meaning only through the enactment of relationships.

Ideas about personhood have moved archaeologists to investigate the role and agency of the deceased as well as their associated burial objects and mortuary structures (Williams Reference Williams2004). By their presence in the funeral, the dead evoke memories for the living and influence the latter's decision making in the selection of objects as well as the creation of social memories within mortuary rituals (Williams Reference Williams2004). The full sequence of death rituals can be considered a dynamic, transformative process for the personhoods of both deceased and mourners (Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román2015). During this crucial transition, these personhoods are reconfigured through processes of dissolution, creation, negotiation, and transformation (Williams Reference Williams2004). This analytical idea is powerful because it permits us to study how the deceased pass from being biologically dead to a transitional stage, and then explore whether or not they later become socially dead. It also facilitates reconstructing the different phases of mortuary practices and exploring the complex relationship between the living and the dead.

Cremation customs, similar to other mortuary practices, are composed of different stages. Cremation, however, further involves the rapid transformation of the deceased's body and subsequent transformation of mourners and the community as well (Kuijt et al. Reference Kuijt, Quinn and Cooney2014). Cremation changes the physicality of the body into fragments and ash that are easily managed and transported. This new materiality engenders different ways for mourners and communities to treat the dead after cremation (e.g., Cerezo-Román et al. Reference Cerezo-Román, Wessman and Williams2017; Kuijt et al. Reference Kuijt, Quinn and Cooney2014). By analyzing different stages of the cremation treatment even after the fire, it is possible to analyze how mourners and the greater society perceived the personhood and embodiment of cremated remains (e.g., part person / part object, or a preference for one over the other). In this study, I compare Tucson Hohokam and Trincheras cremation burial customs in terms of personhood and embodiment in order to understand broader regional interactions between the two traditions.

Contextualizing Cremations

Archaeological studies of cremation (e.g., Beck Reference Beck, Rakita, Buikstra, Beck and Williams2005; Binford Reference Binford and Brown1971; Buikstra and Goldstein Reference Buikstra and Goldstein1973; Parker Pearson Reference Parker Pearson and Hodder1982; Rakita and Buikstra Reference Rakita, Buikstra, Rakita, Buikstra, Beck and Williams2005) have deep roots within mortuary archaeology (Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Kuijt, Cooney, Kuijt, Quinn and Cooney2014). Several authors have addressed significant issues regarding the unique aspects of cremation, the coexistence of cremation and inhumation, and the way cremation is linked with—and yet distinct from—other funerary practices (e.g., Cerezo-Roman et al. Reference Cerezo-Román, Wessman and Williams2017; Kuijt et al. Reference Kuijt, Quinn and Cooney2014; Rebay-Salisbury Reference Rebay-Salisbury, Rebay-Salisbury, Stig Sørensen and Hughes2010; Thompson Reference Thompson2015; Williams Reference Williams, Kuijt, Quinn and Cooney2014).

In North America, archaeological studies of cremation rituals have been conducted at many sites from different time periods. Cremations appear among Paleoindian populations as early as 11,500 years ago (Potter et al. Reference Potter, Irish, Reuther, Gelvin-Reymiller and Holliday2011). Cremation was widely practiced in prehispanic times and has more recently increased in popularity among modern populations (Murad Reference Murad1998). For example, cremation practices were relatively widespread among early Eastern and Midwestern groups (e.g., Baby Reference Baby1954; Binford Reference Binford1963; Goldstein and Meyers Reference Goldstein, Meyers, Kuijt, Quinn and Cooney2014; Robinson Reference Robinson1996; Sanger et al. Reference Sanger, Padgett, Larsen, Hill, Lattanzi, Colaninno, Culleton, Kennett, Napolitano, Lacombe, Speakman and Thomas2019; Schurr and Cook Reference Schurr, Cook, Kuijt, Quinn and Cooney2014; Webb and Snow Reference Webb and Snow1945) and among various groups in California (Hull et al. Reference Hull, Douglass and York2013). In the southwest United States, cremation customs have also been explored among various archaeological groups (e.g., Beck Reference Beck, Rakita, Buikstra, Beck and Williams2005; Brunson-Hadley Reference Brunson-Hadley, Bostwick and Downum1994; Creel Reference Creel1989; Merbs Reference Merbs1967; Reinhard and Fink Reference Reinhard and Fink1982, Reference Reinhard and Fink1994; Reinhard and Shipman Reference Reinhard and Shipman1978; Rice Reference Rice2016; Robinson and Sprague Reference Robinson and Sprague1965; Toulouse Reference Toulouse1944).

Tucson Basin Classic Period Hohokam

The Hohokam were a highly successful agricultural society living in the Sonoran Desert of central and southern Arizona from approximately AD 450 to 1450 (Bayman Reference Bayman2001; Wallace and Lindeman Reference Wallace, Lindeman and Stokes2019). They created large-scale irrigation systems and built villages with communal architecture (Haury Reference Haury1976; Mabry Reference Mabry and Vierra2005). The Classic period (AD 1150–1450) was marked by changes in several aspects of Hohokam culture, including a shift from pit structures to surface-structure courtyard groups with enclosed walls (Clark and Abbott Reference Clark, Abbott, Mills and Fowles2017; Wallace and Lindeman Reference Wallace, Lindeman and Stokes2019), and from ballcourts to platform mounds as centers for communal interaction (Clark and Abbott Reference Clark, Abbott, Mills and Fowles2017; Elson and Abbott Reference Elson, Abbott and Mills2000). There also was a change in ceramic exchange networks and a reduction in the trade of mundane goods, whereas exotic items became increasingly concentrated at platform mound centers (Abbott Reference Abbott2000; Pailes et al. Reference Pailes, Martínez-Tagüeña and Doelle2018; Wallace and Lindeman Reference Wallace, Lindeman and Stokes2019).

Hohokam Mortuary Customs

Past studies of Hohokam mortuary practices focused largely on social organization (Hegmon Reference Hegmon2003; Longacre Reference Longacre2000). Studies of social status and ranking primarily used approaches proposed by Saxe (Reference Saxe1970) and Binford (Reference Binford and Brown1971), emphasizing variation in grave structures and associated objects (Brunson-Hadley Reference Brunson-Hadley1989; Mitchell and Brunson-Hadley Reference Mitchell, Brunson-Hadley, Mitchell and Brunson-Hadley2001). Other studies (McGuire Reference McGuire1992, Reference McGuire, Mitchell and Brunson-Hadley2001) have considered mortuary customs more broadly to discuss social inequalities and other aspects of social organization, such as age, kin, corporate groups (Mitchell and Brunson-Hadley Reference Mitchell, Brunson-Hadley, Mitchell and Brunson-Hadley2001; Neitzel Reference Neitzel and Crown2001; Rice Reference Rice2016), and gender differences (Crown and Fish Reference Crown and Fish1996). From the early Preclassic to the Classic period, cremation was the primary funeral custom for Tucson Basin Hohokam communities (Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román2015; Cerezo-Roman and Watson Reference Cerezo-Román and Watson2020).

Earlier studies of Hohokam cremation mortuary practices were initially conducted using datasets limited to osteological analyses from a single site or published as chapters of archaeological site reports (Birkby Reference Birkby and Haury1976; Fink Reference Fink and Mitchell1988a, Reference Fink, Howard, Barnes and Breternitz1988b, Reference Fink, Mitchell and Breternitz1989; Reinhard and Fink Reference Reinhard and Fink1982, Reference Reinhard and Fink1994; Reinhard and Shipman Reference Reinhard and Shipman1978). More recent studies of Hohokam cremations have examined different stages of cremation mortuary rituals and mourning customs using data from multiple sites (Beck Reference Beck, Rakita, Buikstra, Beck and Williams2005, Reference Beck and Wallace2011; Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román2014), as well as analyzing different aspects of Hohokam funerary customs with respect to changing personhood (Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román2015), architecture and its relationship with group membership (Byrd et al. Reference Byrd, Watson, Fish and Fish2012; Klucas and Graves Reference Klucas, Graves, Harry and Roth2019), social age, and different intersecting identities (Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román, Watson and Rakita2020a, Reference Cerezo-Román, Betsinger, Scott and Tsaliki2020b).

Tucson Basin Sites Included in This Study

Burials from three Tucson Basin Hohokam Classic period archaeological sites—Yuma Wash, Martinez Hill, and University Indian Ruin—were evaluated (Figure 1). These sites were selected based on their relatively high quantity of burials, the availability of the human remains for study, their reported site chronologies, and the presence of contextual information.

Yuma Wash was a village site densely occupied between AD 1150 and 1300, with some features dating from AD 1300 to 1450 (Swartz Reference Swartz2016). It contained pithouses, aboveground adobe-room compounds, extensive evidence of agriculture, and five nearby irrigation canals. Over the past two decades, several studies have analyzed portions of the dataset utilized here (Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román2015; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Whitney, Copperstone, Whitaker, Margolis, Swartz, Lindeman and Swartz2016; Jones Reference Jones1999a, Reference Jones1999b, Reference Jones1999c; MacWilliams Reference MacWilliams2005; McClelland Reference McClelland, MacWilliams and Dart2009; Swartz Reference Swartz2016; Wallace and Swartz Reference Wallace, Swartz and Swartz2016).

The Martinez Hill site had a large Preclassic ballcourt, the Casa Azul complex (a compound with a minimum of 70 rooms), and four platform mounds from the Classic period (Wallace and Lindeman Reference Wallace, Lindeman and Birch2013). Gabel (Reference Gabel1931) and Cummings excavated two of the mounds in 1929 and 1930 and found the burials discussed in this article. Mounds Two and Four were constructed by filling previous special-function rooms and adding construction cells to make the final structures larger (Gabel Reference Gabel1931; Wallace and Lindeman Reference Wallace, Lindeman and Birch2013). There were structures atop Mounds Two and Four as well as attached rooms, indicating at least three to four separate social units linked together in this compound (Wallace and Lindeman Reference Wallace, Lindeman and Birch2013). The fill of Mound Two postdates AD 1257 (Wallace and Holmlund Reference Wallace and Holmlund1984:181–183).

University Indian Ruin was a large Classic period platform mound village that may have been a ceremonial and communal center serving surrounding communities. Four major excavation projects have been conducted at University Indian Ruin, directed by Cummings (1930–1937), Haury (1938–1939), Hayden (1940–1941), and, most recently, Paul and Suzanne Fish (2010–2012; Byrd et al. Reference Byrd, Watson, Fish and Fish2012). These excavations revealed two or three platform mounds, several adobe room blocks, and trash middens (Byrd et al. Reference Byrd, Watson, Fish and Fish2012).

Trincheras Tradition

The Trincheras-tradition sites appear to cluster in the Magdalena, Altar, and Concepción River Valleys of Sonora (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015). The people occupying these sites were agriculturalists, lived in pithouses and households on hillside terraces, and made marine-shell jewelry (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015). The Trincheras tradition shares a border with the Hohokam cultural area to the north. It is best represented at the Cerro de Trincheras site (Figure 1)—whose name means “hill of terraces”—an important regional center situated on a hill along the Magdalena River (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., Fish, Fish and Villalpando2007, Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., Fish and Fish2008, Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015; McGuire et al. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., Vargas, Gallaga M., Schaafsma and Riley1999; Villalpando and McGuire Reference Villalpando and McGuire2009). McGuire and Villalpando C. (Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015:437) suggest that this terraced hill town was built by two groups of Trincheras people: one group that had been displaced from the Altar Valley due to conflict with Hohokam people from the Papaguería, and another group that had been living along the Magdalena River.

The Cerro de Trincheras site was a large settlement occupying over 900 terraces that supported habitation structures, craft workshops, ritual performances, and social gatherings (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., Fish, Fish and Villalpando2007, Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Román, Nava Maldonado, Villalpando C., Schmidt and Symes2015). Occupied from AD 1300 to 1450, the site was contemporaneous with similar cerros de trincheras–type sites in other portions of northwest Mexico and the southwest United States (Downum et al. Reference Downum, Fish and Fish1994; Fish and Fish Reference Fish, Fish, Newell and Gallaga2004, Reference Fish, Fish, Fish, Fish and Elisa Villalpando C.2007; McGuire Reference McGuire1980; McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Canchola, Punzo Díaz and Minnis2015). These cerros de trincheras sites crosscut several archaeological traditions of the Greater Southwest, including the Hohokam, Trincheras, Rio Sonora, and Casas Grandes traditions (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011). Cerros de trincheras sites have also been found in the Altar Valley (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire and Villalpando C.1993) and Tucson Basin (Downum Reference Downum, Fish, Fish and Villalpando2007), reflecting the adoption of hilltop-focused ideology by regional neighbors, with various levels of syncretism (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011; Pailes Reference Pailes2017).

There are around 16 small cerros de trincheras sites within a 75 km radius of the Cerro de Trincheras site, and most contain corrales—dry-laid masonry enclosures—on their summits for performing rituals (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011; Pailes Reference Pailes2017:394). The Cerro de Trincheras site, however, is 17 times larger and covers twice the combined area of all the other cerros de trincheras sites in the region (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015).

Mortuary Practices at Cerro de Trincheras

Trincheras-tradition mortuary customs are not very well understood because the vast majority of the remains studied here come from the Cerro de Trincheras site and not from other sites in the region. The burials from other cerros de trincheras sites have either not been excavated or analyzed. Directly south of the main terraced hill at Cerro de Trincheras lies a smaller contemporaneous pithouse hamlet with a heavily pot-hunted cremation cemetery that has not been excavated (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011). Only 10 inhumations and one cremation were uncovered on the terraces themselves (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011; Villalpando and McGuire Reference Villalpando and McGuire2009).

The large urn-field cemetery, discussed in detail below, was found on the northeastern base of the main terraced hill, and it may date from approximately AD 781 to 1395 (Villalpando et al. Reference Villalpando, Guzmán and Maldonado2009). The earlier date could have resulted from the use of old wood, gathered from the Sonoran Desert, in the cremation fires (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011). Villalpando's most recent project at the Los Crematorios site, located a few hundred meters from the northwest end of the Cerro de Trincheras hillside, identified another variant of the mortuary ritual: an area of cremation pyres and two inhumations (Villalpando et al. Reference Villalpando, Guzmán and Maldonado2009). Preliminary analysis (Cerezo-Román et al. Reference Cerezo-Román, Nava Maldonado, Cruz, Watson and Villalpando2018) found that this area was mainly used for burning individuals on pyres as part of cremation rituals. These rituals were performative acts that would have stimulated the senses of the mourners, funeral participants, and members of the broader community. Although some aspects of the cremation pyres were reasonably standardized, others were not, indicating flexibility in practices among the participants (Cerezo-Román et al. Reference Cerezo-Román, Nava Maldonado, Cruz, Watson and Villalpando2018). A detailed analysis of the pyres is in progress for future publication in a separate article.

Samples and Methods

To evaluate the funeral customs among the Tucson Basin Hohokam, a total of 282 cremation deposits from three sites was examined: 15 deposits from Martinez Hill, 28 deposits from University Indian Ruin, and 239 deposits from Yuma Wash. For Cerro de Trincheras, a total of one pyre and 115 secondary cremation deposits was analyzed from the urn-field cemetery (Table 1). Inhumations were found in low frequencies at all sites (Cerro de Trincheras: 12 out of 116; Yuma Wash: 77 out of 239; University Indian Ruin: 1 out of 28; and Martinez Hill: 5 out of 15; Table 1). The samples from the Tucson Basin and Cerro de Trincheras were selected based on the following criteria: (1) they were not significantly disturbed, (2) they had reported chronologies, and (3) each contained the remains of a single individual.

Table 1. Funerary Features and Individual Attributes by Site.

Note: This is a presence/absence dataset organized by the attributes that could be observed or estimated on individuals found at each site. It was not possible to observe all attributes in all individuals. For example, it was only possible to estimate the sex for 15 individuals from Yuma Wash. The counts will not add up to the total number of individuals.

aAge category of ≥15 years was used for adults and individuals who—in terms of size, morphology, and degree of development—were consistent with adults but could not be differentiated between adolescent (more than 12 and less than 18 years) and adult (over 18 years) because of the degree of fragmentation, thermal alteration, or both.

Biological Profile of the Cremated Human Remains

The biological profile estimates used for this study were age at death and biological sex. The protocols for osteological data collection were based primarily on those of Buikstra and Ubelaker (Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994), subsequent revisions to some of those methods (Scheuer and Black Reference Scheuer and Black2000), and the protocols of the Bioarchaeology Laboratory of the Arizona State Museum (ASM; Arizona State Museum 2018). Skeletal data collection consisted of morphological information. First, a detailed skeletal inventory of each burial was generated. These data were used to infer the number of individuals represented in each deposit as well as body completeness. Second, age at death, with error ranges, and biological sex were estimated for each individual.

Next, individuals were classified into broader categories for analytical purposes, such as subadult (infants, children, and adolescentsFootnote 1), adults (individuals older than 18 years), and an additional category of older than 15 years. This last category was used for individuals who, in terms of size, morphology, and degree of development, were consistent with adults but could not be differentiated between adolescent (more than 12 and less than 18 years) and adult (over 18 years) because of the degree of fragmentation, the degree of thermal alteration, or both. In these cases, individuals assigned to this category were combined with the adults for analyses and were not duplicated in the adolescent category. The degree of fragmentation for cremated bone limited certain analytical observations—including some bone identification, age at death, sex, and pathologies—although these estimations were attempted when possible.

Posthumous Treatment of the Remains and Archaeological Context

Posthumous treatment of the body was inferred through observations of the skeletal remains and examination of contextual data from archaeological field notes, reports, and published analyses. Thermal alteration and postfire body treatment were documented to reconstruct in detail the posthumous treatment of remains from pyres and secondary deposits. Secondary deposits refer to deposits with recoverable bone in a secondary location to which cremated human remains were relocated after removal from the pyre or crematorium. These deposits can have a wide range of bone in them and yet not reflect anatomical relationships. They can consist of (1) simple pits that lack burned soil but have bone in them or (2) pits that contain cremated bone in and/or around ceramic vessels or sherds.

Following data-collection protocols proposed by Cerezo-Román (Reference Cerezo-Román2014), the recorded variables included bone weight as well as the color, degree, and type of shrinkage and fractures caused by fire. Adult cremation weights were used to evaluate how the burned remains were treated after being exposed to fire. A typical cremated adult's bones are expected to weigh over 1,500 g, whereas adult bone weights below this would imply that not all of the remains were present (Bass and Jantz Reference Bass and Jantz2004; Sonek Reference Sonek1992; Trotter and Hixon Reference Trotter and Hixon1974). Subadult bone-weight differences were not explored because there were no comparable published data. Bone weights can vary for many reasons, including differential funeral treatment, postdepositional disturbances, archaeological excavation, and analysis procedures. Therefore, only deposits with no major postdepositional disturbance were selected for this study for comparison. Specific excavation protocols and techniques were used to optimize recovery of human remains by the author, archaeologists from the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, and various CRM personnel. The chronological period for the remains, as estimated by the archaeologists, was recorded from field notes and reports. The variables in posthumous body treatment were integrated with the osteological information, reconstructions of posthumous treatments, and intersite data comparisons. Statistical analyses employed software programs such as SPSS Statistics 19 and Microsoft Office Excel 2016.

Results

Cremation, particularly secondary deposition of cremated bone, was found to be the main burial custom at all of the study sites in the Tucson Basin and Cerro de Trincheras (Table 1). Males, females, and individuals of different age groups were cremated, with no apparent age- or sex-based selection (Table 1). At Cerro de Trincheras, most pyres were located in a separate area. Preliminary data from this area, however, suggest that most of the remains at Cerro de Trincheras were collected and placed in secondary deposits in the urn-field cemetery and not left on the pyres themselves (Cerezo-Román et al. Reference Cerezo-Román, Nava Maldonado, Cruz, Watson and Villalpando2018; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Román, Nava Maldonado, Villalpando C., Schmidt and Symes2015). In contrast with Cerro de Trincheras, bones from secondary deposits in the Tucson Basin varied in their placement inside the pit. Remains from Yuma Wash were found in simple pits, with the bones placed under or inside vessels, whereas at Martinez Hill and University Indian Ruin, they were found mainly inside vessels in the secondary deposits (Table 1).

The thermal alteration of the remains was fairly similar at Cerro de Trincheras and the Tucson Basin sites. The predominant (>75%) color of the cremated remains is a proxy for the extent and temperature of the burning in the pyre, which in both samples was white (Table 2). The similarities in color and the white coloration suggest that the remains were mostly calcined, indicating that they were burned very efficiently. Quantifying mean bone weights of cremations allows for exploring the average amount of bone present in the deposits (Table 2). Differences in mean bone weights of the cremations were examined for adult individuals exclusively. The bone weights for subadults were not included in this study because subadult bone weights from modern control cremations were not available for comparison. Secondary cremations from the three Tucson Basin Classic period sites had a mean bone weight of 362.7 g, whereas the mean weight of the remains from the pyres was 323.72 g (Table 2). At Cerro de Trincheras, the mean bone weight of secondary cremation deposits was 752.24 g (Table 2), whereas remains from the only pyre found at the urn field weighed 553 g. These mean weights indicate that less bone was placed in secondary deposits in the Tucson Basin in comparison to Cerro de Trincheras.

Table 2. Adult Cremation Colors and Bone Weights (g) by Geographical Region.

aWeights are from undisturbed cremations.

bMultiple modes exist. The smallest value is shown.

Evaluated individually, there were variations in bone weights in pyres and secondary deposits between sites (Figure 2). Martinez Hill and Cerro de Trincheras showed fairly similar mean bone weights in secondary deposits, suggesting similar practices of placing bone in the deposits between these two sites, even though they are from different regions (Figure 2). In contrast, the mean bone weights for adult individuals were similar in the secondary deposits at Yuma Wash and University Indian Ruin, suggesting that individuals placed similar quantities of bones in the deposits (Figure 2). At Yuma Wash, Martinez Hill, and Cerro de Trincheras sites, the weight of bone inside vessels and the weight of bone found in pits without vessels ranged from ≤1 to 1,500 g (Table 3). When the mean bone weight of adults was compared with modern adult cremated remains, the total bone weights for the prehispanic samples were somewhat higher for the Cerro de Trincheras and Martinez Hill deposits (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Adult cremation mean weights (g) in modern versus prehispanic examples.

Table 3. Cremations Mean Weight (g) and Location of Bones within Burial.

A major difference between the sites in the Tucson Basin and Cerro de Trincheras was the location of the inhumations and secondary deposits. Most of the inhumations at Cerro de Trincheras were found on the hill (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011; Villalpando and McGuire Reference Villalpando and McGuire2009). The secondary cremated deposits from Cerro de Trincheras were mainly found in a large communal cemetery at the bottom of the hill (see Cerezo-Román et al. [Reference Cerezo-Román, Nava Maldonado, Cruz, Watson and Villalpando2018] and Watson et al. [Reference Watson, Román, Nava Maldonado, Villalpando C., Schmidt and Symes2015] for illustrations and photos of the site). By contrast, most of the inhumations from the Tucson Basin were found next to the cremations (Byrd et al. Reference Byrd, Watson, Fish and Fish2012; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Whitney, Copperstone, Whitaker, Margolis, Swartz, Lindeman and Swartz2016; Wallace and Lindeman Reference Wallace, Lindeman and Birch2013; Wallace and Swartz Reference Wallace, Swartz and Swartz2016). The cremations at Yuma Wash, University Indian Ruin, and Martinez Hill were placed under the floors of rooms and/or in much smaller cemeteries associated with habitational structures (see Figure 3 for an example of a cemetery). At Yuma Wash, 36 small cemeteries containing from one to 43 individuals were found in just two loci (Locus AZ AA:12:122 [ASM] and Locus AZ AA:12:311 [ASM]), whereas four burials with no apparent grouping were found at a third locus (Locus AZ AA:12:314 [ASM]; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Whitney, Copperstone, Whitaker, Margolis, Swartz, Lindeman and Swartz2016; Wallace and Swartz Reference Wallace, Swartz and Swartz2016). Only 28 individuals (27 secondary cremations and one individual in a pyre) were found at University Indian Ruin, whereas 15 individuals in secondary cremation deposits were from Martinez Hill. Most Hohokam cemeteries from the sample sites had pyres (see Figure 4 for an example of a pyre) and secondary cremation deposits, except for Martinez Hill, where only secondary cremation deposits were documented.

Figure 3. Example of Hohokam cemeteries near residential areas. Created by Catherine Gilman. Courtesy of Desert Archaeology Inc., Tucson, Arizona.

Figure 4. Example of pyre at Yuma Wash. Created by Susan Hall. Courtesy of Desert Archaeology Inc., Tucson, Arizona.

Discussion

Hohokam and Cerro de Trincheras Connections

The Cerro de Trincheras site and the Tucson Basin Classic period Hohokam sites examined in this study developed separately and were distinct but contemporaneous archaeological groups. Little evidence has been found of connectivity between Cerro de Trincheras and the Hohokam area (e.g., McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011; McGuire et al. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., Vargas, Gallaga M., Schaafsma and Riley1999; Punzo Díaz and Villalpando Canchola Reference Díaz, Luis, Elisa Villalpando Canchola, Minnis and Whalen2015; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Román, Nava Maldonado, Villalpando C., Schmidt and Symes2015). The population at Cerro de Trincheras has been described as a society minimally involved in long-distance exchange (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011; O'Donovan Reference O'Donovan2002; Pailes Reference Pailes2017). Pailes (Reference Pailes2015) argues that populations in northern Sonora were of moderate density, segmented into small independent polities with limited connectivity and in relative isolation from other regions socially. McGuire and Villalpando C. (Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011), Villalpando (Reference Villalpando2012), and Punzo Díaz and Villalpando Canchola (Reference Díaz, Luis, Elisa Villalpando Canchola, Minnis and Whalen2015) suggest that the population of Cerro de Trincheras probably interacted more with the residents of Paquimé in Chihuahua, Mexico, than with the Hohokam.

Trincheras painted pottery types occasionally have been found at Preclassic (AD 475–1150) Hohokam sites (Fish and Fish Reference Fish, Fish, Fish, Fish and Elisa Villalpando C.2007), but ceramic evidence of direct trade is lacking in both regions (McGuire et al. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., Vargas, Gallaga M., Schaafsma and Riley1999; McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., Fish, Fish and Villalpando2007, Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011). McGuire and Villalpando C. (Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015) note that in the Classic period, around AD 1300, the Hohokam tradition replaced the Trincheras tradition in the Altar Valley, and the inhabitants from the area moved and aggregated in the Magdalena Valley.

There is a fairly direct route between the northern Sonoran heartland and Tucson Basin via the Magdalena River, which originates north of Cerro de Trincheras (Figure 1). The river valley serves as a corridor leading toward the upper reaches of the Santa Cruz River, which flows north through the Tucson Basin (Fish and Fish Reference Fish, Fish, Fish, Fish and Elisa Villalpando C.2007). Many cerros de trincheras sites occur along this route (Fish and Fish Reference Fish, Fish, Fish, Fish and Elisa Villalpando C.2007; Fish et al. Reference Fish, Fish and Elisa Villalpando C2007; McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire and María Elisa2015). Fish and Fish argue that the “constellation of trincheras concepts and its archaeological manifestations” (Reference Fish, Fish, Fish, Fish and Elisa Villalpando C.2007:165) appeared first in the Sonoran Trincheras culture sequence and subsequently was adopted by the Tucson Basin Hohokam. They further suggest that the presence of cerros de trincheras sites along the route between the Sonoran heartland and the Tucson Basin could imply a unified phenomenon at some fundamental level, but with local variations across regions and cultural traditions (Fish and Fish Reference Fish, Fish, Fish, Fish and Elisa Villalpando C.2007). In both the Altar and Magdalena Valleys, intervisibility between both contemporary and ancestral cerros de trincheras sites is common and might have been important for larger scales of integration and hilltop rituals (Pailes Reference Pailes2017; Zavala Reference Zavala, Van Pool, Van Pool and Phillips2006).

It is also notable that cremation was the main burial custom for both the Trincheras people and the Tucson Basin Hohokam, whereas at Paquimé, Chihuahua, inhumation was the primary mortuary practice (Di Peso Reference Di Peso1974; Rakita Reference Rakita2009; Whalen and Minnis Reference Whalen and Minnis2001a, Reference Whalen and Minnis2001b, Reference Whalen and Minnis2003, Reference Whalen and Minnis2009).

Could the treatment of the dead—particularly cremation—be related to a fundamental unity, at a regional level, between the Tucson Basin Hohokam and Cerro de Trincheras? It is indeed a possibility. Analyzing the differences and similarities in mortuary rituals and their stages allows a deeper understanding of the social interactions between both regions, as well as the broader aspects of ideologies related to personhood and embodiment.

Transformation of the Body in Mortuary Rituals

The human body is constituted, in part, by its relation to people and things. Meskell (Reference Meskell2000) and Hampson (Reference Hampson2016:219), among others, suggest that studies of just “the body”—in which analytical stress is placed on the body as a socially inscribed and passive object—ignore the individual per se. By contrast, embodiment emphasizes the diversity of bodies as lived experiences. It captures the notion of making and doing the work of bodies as well as becoming a body in social space (Hampson Reference Hampson2016:219). Bodies are more than constructed social objects controlled and manipulated by institutions of power or the living. They are also more than just passive reflectors of large-scale social processes. Instead, bodies are objects and subjects at the same time. This becomes clearer when we put them into the context of mortuary rituals.

The dead do not bury themselves. It is mourners who create the deposits (Parker Pearson Reference Parker Pearson1999). But mortuary customs are not all about the living. Restricting the study to the living completely ignores the dead as individuals and sources of remembrance. The dead influence the living through their identity in life and death as well as the ways they are remembered by the living (Williams Reference Williams2004). Through its presence in mortuary ritual, the deceased body evokes memories. It thereby alters the decision making of mourners and the broader community with regard to the ways bodies are treated. For the Tucson Basin Hohokam and Trincheras traditions, archaeological evidence of such decision making could consist of the choice between inhumation and cremation, as well as how remains were disposed of.

Inhumations in Context

Although inhumations were found in low frequencies in both areas (see Table 1), the practice of inhumation cannot be underestimated when studying the burial customs of the Trincheras and Tucson Basin Hohokam traditions. The decision to inhume a family member likely represents multiple and even contradicting beliefs within a society (Cerezo-Román and Watson Reference Cerezo-Román and Watson2020). The co-occurrence of inhumation and cremation among the Tucson Basin Hohokam sites in the Classic period has been discussed elsewhere (see Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román, Betsinger, Scott and Tsaliki2020b). Classic period Tucson Basin inhumations were located in cemeteries inside courtyard groups, close to where cremations were found. The association of inhumations juxtaposed with cremations suggests that inhumed individuals possessed similar relationships as cremated individuals within the smaller groups, and this also may indicate that inhumed individuals were an integral part of the community (see Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román, Betsinger, Scott and Tsaliki2020b). Among the Tucson Basin Hohokam, infants usually were inhumed rather than cremated (Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román2014, Reference Cerezo-Román2015, Reference Cerezo-Román, Watson and Rakita2020a, Reference Cerezo-Román, Betsinger, Scott and Tsaliki2020b) and, on occasion, they were buried within residential units. This suggests that infant status, as a social age category, was an important variable in deciding how bodies were treated and how personhood was acquired (Cerezo-Roman Reference Cerezo-Román2015). Perhaps personhood was acquired gradually, as the individual established connections outside the household and reached the social age at which one was considered a full member of society. In contrast, these marked differences in age and treatment were not found at Cerro de Trincheras, suggesting that, for the Trincheras people, personhood acquisition might not have been tied to social age at death.

Inhumation, however, more than cremation—particularly of adults—seems to have been a way for Tucson Basin people to display different social and economic relationships (Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román, Betsinger, Scott and Tsaliki2020b). This was possibly signaled by the quantity and variability of the objects placed with the deceased and the burial treatment (i.e., inhumation; Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román, Betsinger, Scott and Tsaliki2020b). In comparison, at Cerro de Trincheras, 10 inhumations were found on the hill itself, including 11 individuals (seven subadults and four adults), and two adults in the pyre area (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011; Villalpando and McGuire Reference Villalpando and McGuire2009; Villalpando et al. Reference Villalpando, Guzmán and Maldonado2009). Only two of these burials contained offerings (McGuire and Villalpando C. Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011:830). McGuire and Villalpando C. (Reference McGuire, Villalpando C., McGuire and Villalpando2011:830) suggest that the co-occurrence of inhumations and cremations at Cerro de Trincheras might be similar to that of the Hohokam. Building on their proposal, I argue that the locations of the inhumations on the hill and in the pyre site could be one way to socially differentiate these individuals from the other members of the community buried in the urn-field cemetery. It is possible that, for the residents of Cerro de Trincheras, the practice of inhumation had multiple meanings. However, due to the limited archaeological data and lack of other contemporary sites in the area for comparison, there may be alternative explanations as to why these individuals were not cremated. These include adverse weather conditions, shortage of fuel, and lack of social cooperation (Cerezo-Roman Reference Cerezo-Román, Betsinger, Scott and Tsaliki2020b; Squires Reference Squires, Cerezo-Román, Wessman and Williams2017).

Cremations in Context

As previously noted, at Cerro de Trincheras and in the Tucson Basin, cremation was the main burial custom. Unlike inhumation, cremation usually involved an extra step—the creation of a secondary deposit. In order to deconstruct, compare, and contrast these different stages between regions, this discussion is divided into sections on preburning, burning, and postburning practices.

Preburning and Burning in Cremation Rituals

In a cremation, first the body is prepared for placement on a pyre. The location of the pyre was different between the two regions. The pyres in the Tucson Basin were mainly found in small to medium-sized cemeteries adjacent to residential structures, whereas the majority of the pyres at Cerro de Trincheras were east of the site, away from the urn-field cemetery. At least one poorly preserved pyre was found at the urn-field cemetery, but based on the excavations, this was not the main area for burning. Various items were also placed with the dead on the pyre and burned (Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román2016, Reference Cerezo-Román, Watson and Rakita2020a, Reference Cerezo-Román, Betsinger, Scott and Tsaliki2020b; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Román, Nava Maldonado, Villalpando C., Schmidt and Symes2015).

In both the Trincheras and Tucson Basin Hohokam traditions, deceased individuals were burned as complete bodies in what is inferred to have been a reasonably similar manner, given that the remains were predominantly calcined (Cerezo-Román Reference Cerezo-Román2015, Reference Cerezo-Román, Watson and Rakita2020a; Cerezo-Román et al. Reference Cerezo-Román, Nava Maldonado, Cruz, Watson and Villalpando2018; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Román, Nava Maldonado, Villalpando C., Schmidt and Symes2015; Table 2). This suggests an equally efficient pyrotechnology in the pyres and that temperatures were above 600°C (Binford Reference Binford1963; Gonçalves and Pires Reference Gonçalves and Pires2017; Schultz et al. Reference Schultz, Warren, Krigbaum, Schultz and Symes2015; Thompson Reference Thompson2015).

Postburning and Final Deposition in Cemeteries

In a cremation, a body's transformation by a fire could destroy, reconceptualize, and/or maintain concepts of embodiment and group identity, in part because cremation rituals also involve a stronger community investment through the use of secondary burial. After the fire, in both traditions, the remains were not usually left on the pyres after burning. Instead, the bone fragments were collected and placed in an urn or pit and buried as part of a secondary cremation deposit. The act of removing or leaving the remains in the pyre, or placing them in an urn or a pit can be reconstructed by analyzing the quantity of an individual's recovered bones.

Compared to modern adult cremations, which usually weigh more than 1,500 g, the Trincheras cremations did not represent complete bodies. Considering, however, that they were archaeological samples and that a fraction of the remains may have stayed on the pyre or been destroyed by the fire, the mean bone weights from adult cremations were reasonably high. The remains still represented fairly complete bodies, not token burials (Figure 2). Similarly, at Martinez Hill, the residents collected the vast majority of the bones from the pyres and put them in urns (Tables 1 and 3). These practices indicate that even when the body of the dead was transformed into bone fragments, it was still treated as a single unit. Whether or not the remains were placed in a vessel—and how much bone was deposited inside it—does not seem to have contributed significantly to the high bone weights (Table 3).

At Yuma Wash and University Indian Ruin, the secondary deposits had fewer bones represented, suggesting that, in general, the residents were not treating the remains as a complete unit after the fire (Figure 2). There was also more variation in bone weights at Yuma Wash, which may indicate a more diverse community reflecting a wider array of concepts of personhood and embodiment at the end of the funeral ritual (Table 3). In contrast, cremation practices at Cerro de Trincheras and some Tucson Basin sites suggest that even when the deceased's body was transformed into bone fragments, it was still treated as a single unit.

Commemoration, Remembrance, and Personhood at Cerro de Trincheras

At Cerro de Trincheras, individuals of all age groups and sexes were buried in the urn-field cemetery (Cerezo-Román et al. Reference Cerezo-Román, Nava Maldonado, Cruz, Watson and Villalpando2018; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Román, Nava Maldonado, Villalpando C., Schmidt and Symes2015). Mourners and persons who knew the deceased could view the fire, smell its smoke, and also see when the urns were placed. The cemetery's high visibility suggests personal and active participation by the viewers, and this could have created an indelible memory of a particular decedent. The visibility of the cemetery may also have helped the community to both deal with the loss of and remember the deceased. When viewed from afar, the differences between urns would not have been apparent. The homogeneity in treatment seen at the site may suggest a ritual that emphasized a collective—rather than individual—identity for the deceased (Cerezo-Román et al. Reference Cerezo-Román, Watson, Villalpando C., Cruz and Nava Maldonado2012; Watson et al. Reference Watson, Román, Nava Maldonado, Villalpando C., Schmidt and Symes2015). The treatment of the bodies suggests a more unified view of personhood and embodiment, with only minor differences between individuals. Over time, the memories of individuals buried in the urn-field cemetery became indirect and referential, transforming them into a collective ancestry (Cerezo-Román et al. Reference Cerezo-Román, Nava Maldonado, Cruz, Watson and Villalpando2018). In addition, the creation of a cemetery close by, where these vessels were placed, created a social context for community cohesion and shared membership over time. As new cremations occurred, they would engender memories of previous funerals. Over time, a cremation tradition was created as a way to commemorate the dead and remember the past.

Commemoration, Remembrance, and Personhood in the Tucson Basin

Compared to the occupants of Cerro de Trincheras, the Tucson Basin Hohokam seem to have had a different way of remembering and commemorating the dead. No communal cemetery of a size comparable to that of the Cerro de Trincheras cemetery has been found at the other sites included in this study. Although there are Tucson Basin Classic period sites with large cemeteries, such as Muchas Casas (Henderson Reference Henderson1987; Morris and Brooks Reference Morris, Brooks and Rice1987), which could represent cemeteries for a large social unit (Wallace and Swartz Reference Wallace, Swartz and Swartz2016), Tucson Basin cemeteries were smaller than the urn field of the Cerro de Trincheras, based on the available data.

Numerous researchers have explored spatial patterns of Hohokam burials and their relationship to residential architecture (Anderson Reference Anderson, Antieau and Gasser1986; Byrd et al. Reference Byrd, Watson, Fish and Fish2012; Effland Reference Effland and Howard1988; Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Fink, Allen and Mitchell1989), and some have argued that individuals buried in platform mounds may have had roles related to the control of resources or religious leadership (e.g., Anderson Reference Anderson, Antieau and Gasser1986; Doyel Reference Doyel, Fish and Fish2007; Effland Reference Effland and Howard1988; Fish and Fish Reference Fish, Fish and Mills2000; Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Fink, Allen and Mitchell1989). In addition, families could visit the burial location and cemetery to claim a connection to the area and any architectural units associated with the cemeteries.

Craig (Reference Craig and Beck2007, Reference Craig2010) proposed that individual habitational structures were arranged so as to create an exterior courtyard space—presumably for corporate use, including burials of group residents—that represented continuity in control over space and resources by a single domestic unit through generations. Byrd and colleagues (Reference Byrd, Watson, Fish and Fish2012) argue that the act of interring members of the lineage within or around an architectural unit, as opposed to an external cemetery shared by multiple lineages, may have been intended to legitimize a “house's” connection to property rights, especially to land. Klucas and Graves (Reference Klucas, Graves, Harry and Roth2019) suggest that membership in a courtyard group did not require a shared kinship, but that kinship still played an important role. Other residential localities existed as well, and individuals may have established and maintained residences at those other locations, returning periodically to the original courtyard groups and associated cemetery for mortuary ceremonies or other activities that reinforced group membership. Studies by Klucas and Graves (Reference Klucas, Graves, Harry and Roth2019) and Byrd and colleagues (Reference Byrd, Watson, Fish and Fish2012) highlight a cross-cultural pattern, previously proposed by Saxe (Reference Saxe1970) and reformulated by Goldstein (Reference Goldstein1976), in which formal disposal areas, such as cemeteries, generally are used by corporate groups to claim lineal ties to the ancestors to control access to crucial but restricted resources and territory. Klucas and Graves (Reference Klucas, Graves, Harry and Roth2019) and Byrd and colleagues (Reference Byrd, Watson, Fish and Fish2012) focus on the mourners and their rights almost exclusively. Here, I build on their work by considering the dead as a source of remembrance and commemoration from the perspective of embodiment and personhood.

In the Tucson Basin, the locations of the cremation burials suggest a stronger connection to, and remembrance of, specific deceased individuals within the nuclear groups, rather than the burial rituals of the broader social group. This indicates that the embodied personhood of these individuals in the Tucson Basin persisted even though the fire transformed the remains into small bone fragments and ash. This idea is also reinforced by the presence of the inhumations near the cremations. The final stages of the mortuary ritual emphasized the mourners’ and the decedent's smaller nuclear-group identities, and not the identity of the broader community. At the site level, this could be tied to a more diverse—and possibly multiethnic—community.

In the Tucson Basin, the pyres, inhumations, and secondary burial deposits were not located in communal spaces of the same magnitude as those found at Cerro de Trincheras. Instead, only members of a household and family group had access to the burial location and even the pyres. The broader social group did not have regular access to these spaces because they were usually enclosed by a wall that limited the visibility of the specific burial locations. The placement of the dead in proximity to the living provided the latter with a more intimate and direct connection as well as a constant reminder of their lineage, founding members, family group history, and traditions. Keeping the bones in separate spaces as single units preserved the individual memory and individuality of the dead.

The mortuary rituals of the Tucson Basin and the Cerro de Trincheras populations had many similar patterns. For example, the practice of inhumation may have been one way to differentiate the social significance of some of their members. In the cremation funeral ritual, bodies were treated and burned similarly, suggesting a shared view of the body, at least in the initial stages. The various stages of mortuary rituals also show some differences in concepts of emerging personhood and, possibly, embodiment. Practices diverge significantly in the case of the inhumations, in which differences between individuals in the society were indicated by the location of burials (in the case of Cerro de Trincheras) and by the quantity and variability of objects (in the case of the Tucson Basin). Regarding cremation, differences were found after the burning stage and in the final deposition rituals, indicating different notions of personhood and embodiment.

Conclusions

This article explores the similarities and differences in mortuary practices at three Hohokam Classic period Tucson Basin archaeological sites in southern Arizona and an urn-field cemetery at the Cerro de Trincheras site in northern Sonora. Both areas have extensive and well-documented archaeological data and numerous cremation deposits. The rich contextual information and detailed analyses from the sites provided the opportunity to explore cremations and mortuary customs in new and innovative ways. My approach consisted of an in-depth evaluation of all stages of the mortuary ritual and facilitated a holistic way to explore the intricate connections between the deceased, the mourners, and the community—both among and between the Tucson Basin and Cerro de Trincheras groups. In both regions, inhumation, on certain occasions, was one way that the mourners marked social and economic differences. Analysis of Tucson Basin cemeteries and burials suggests a stronger connection to, and remembrance of, specific deceased individuals within their respective groups, in addition to a wider array of concepts of personhood and embodiment. These findings are perhaps reflective of a more diverse community, rather than a focus on communal burial ritual. In contrast, burial practices at Cerro de Trincheras emphasized similarities among the individuals, with rituals directed toward the broader collective social group as well as a unified view of personhood and embodiment. Cerro de Trincheras and the Tucson Basin are interpreted as fundamentally similar in the way they initially treated the bodies of the dead but fundamentally different in the way the dead were transformed through the life-and-death continuum.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Tobi Lopez Taylor, Thomas Fenn, and Marijke Stoll for their help and support. I am grateful for suggestions made by Barbara Mills, Jane Buikstra, Suzanne Fish, John McClelland, and Tom Sheridan at different stages of the research. Access to Tucson Basin collections and documentary materials was granted by Lane Beck, Alan Ferg, the ASM Bioarchaeology Laboratory, the ASM library, and the Tohono O'odham Nation. I also am very grateful for the support of Henry Wallace, Sarah Herr, Deborah L. Swartz, Michael W. Lindeman, and William H. Doelle of Desert Archaeology Inc., as well as Joe Ezzo of SWCA Environmental Consultants. I appreciate the help of Michael Margolis for accessing some of the data and field notes. I would like to thank Matthew Pailes for producing the map for this publication. The Tucson Basin research was partially supported financially by the William Shirley Fulton Scholarship (School of Anthropology, University of Arizona [UA]), the Raymond H. Thompson Endowment Research Award (ASM, UA), and a National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant (DDRIG# 1132395). Excavation, analyses, and reporting of the Centro de Visitantes locus (the urn field at Cerro de Trincheras) were funded by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), Mexico. Elisa Villalpando Canchola and INAH granted access to the Cerro de Trincheras collections and documentary materials. I would also like to thank Elisa Villalpando Canchola, James T. Watson, Silvia I. N. Maldonado, and Carlos C. Guzmán for their help and support. I greatly appreciate the assistance of Greg Hodgins at the University of Arizona–National Science Foundation AMS Laboratory and the support of Mark van Strydonck and the carbon-14 dating laboratory staff at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Brussels, in dating the cremated remains from Cerro de Trincheras.

Data Availability Statement

All osteological inventories and field notes for this study are stored in the Bioarchaeology Laboratory, Department of Anthropology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma; and the Bioarchaeology Laboratory, ASM, Tucson, Arizona. All data are available upon request from the author.