Introduction

World War II brought about upheavals across the colonial world, overturning imperial loyalties, breaking connections with metropoles, and challenging some of the underpinnings of empire. Each of these transformations can be identified in the Indochinese case. As this chapter will show, maritime ties with France were virtually severed in late 1941. Moreover, a Japanese occupation lasting four years tested French colonial authority. Last but not least, the era profoundly altered local identity politics. Although it is important to avoid teleology, there can be no doubt that the war years in Indochina imprinted both the moments of independence and the revolutions that emerged from them across the Indochinese peninsula.

Watersheds

French authorities in Indochina felt threatened by Japanese advances in China through the 1930s. Indochina’s governor, Georges Catroux, faced a deluge of Japanese threats – including an ultimatum – in 1940, before being dismissed. A decree signed in Bordeaux on June 25 (the very day on which the Armistice sealing France’s defeat to Germany went into effect), and sent to Indochina five days later, named Admiral Jean Decoux the new governor-general of Indochina.Footnote 1 A career navy man with extensive prior service in the Pacific, Decoux had been named head of French naval forces in the Far East in 1939. With the blessing of Marshal Philippe Pétain’s new Vichy regime, Decoux signed preliminary agreements with Japan in September 1940 that allowed Japanese troops to enter northern Indochina, paving the way for economic cooperation between Indochina and Japan.

Tokyo alternated using carrots and sticks to gain a foothold in Indochina.Footnote 2 Thus, in September 1940 Japanese forces staged a coup de force against the French garrison at Lạng Sơn, killing some 150 defenders. In July 1941, new agreements were ratified between Tokyo and Vichy allowing Japan to station its troops across Indochina (including the South – prior to then they had only been present in the north), thus enabling Japan to use the colony as a launching pad for their planned operations against British Malaya.

The precarious coexistence that ensued entailed a sort of dual colonialism, French and Japanese. In one sense, it preserved French interests. While the British were removed from Singapore, Hong Kong, and Malaya, the Dutch from Indonesia, and the Americans from the Philippines, French Indochina remained the last functioning European colony on the continent, to the east of the British Raj. On the other side of the equation, Tokyo saw the utility in keeping this particular colonial structure in place, especially since Vichy was a de facto partner of Nazi Germany, an ally of Tokyo’s.

With France weakened by the 1940 defeat, and unable to send reinforcements to Indochina, Thailand (previously Siam) decided to seize territories in Cambodia and Laos on which it had long made irredentist claims. While Thai troops made headway on the ground, the French navy scored a victory over Thai vessels at Ko Chang on January 17, 1941. However, Japan brokered a peace that proved favorable to Thailand, forcing Decoux to cede to Bangkok some 19,000 square miles (50,000 square kilometers) of western and northern Cambodia as well as smaller strips of Laos.Footnote 3

The next major political upheavals in Indochina occurred in March 1945. The argument for Japan’s accommodation of Vichy crumbled in 1944–5, after Paris was liberated and Vichy evaporated. The Japanese finally chose to strike on March 9, 1945, and liquidate French rule once and for all. Emperor Bảo Đại became the ephemeral head of state of a new national Vietnamese government, the Empire of Vietnam; Laos and Cambodia claimed their independence. Each nation operated within the orbit of the empire of the rising sun. However, only five months later, Japan was forced to surrender. The ensuing power void rendered the August 1945 Revolution – and the rise of Hồ Chí Minh and his Việt Minh movement – possible. Only the Việt Minh could claim to have battled both colonizers, French and Japanese.

The “Double Yoke” of Oppression

Hồ Chí Minh famously dubbed the uneasy dual control over Indochina by Vichy French and Japanese from July 1940 to March 1945 a “double yoke” of oppression.Footnote 4 Although the expression certainly makes clear that Indochina was abruptly dominated by two occupiers, rather than one, it nevertheless poses several problems. In particular, the phrase tends to flatten the extraordinarily complex relations between Japanese, French, Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians.

A series of agreements signed between Tokyo and Vichy in 1941 provided Japan with the use of bases in Indochina, as well as linking the two parties economically. Indeed, with trading relations between Indochina and France virtually severed after Pearl Harbor (December 1941), it is no exaggeration to suggest that Indochina jumped from one orbit to another, entering the gravitational pull of the so-called Japanese co-prosperity sphere. As early as 1942, Japan received a staggering 94.6% of all Indochinese exports, and provided 77.7% of Indochinese imports. That same year, French Indochina accounted for 12.8% of all of Japan’s total imports.Footnote 5

A glimpse at the goods slated to be imported into Indochina in 1943 and 1944 reveals a relationship of utter dependency. Medications, canned sardines, cement, pens and pencils, and bicycle parts were all now purchased by Hanoi from Japan. In the opposite direction, in 1943–4, Vichy’s governor, Jean Decoux, agreed to provide at least 900,000 tons of Indochinese rice to Japan before the end of December 1944, as well as “any surplus.” This decision constituted one of the contributing factors to the devastating famine that ravaged Tonkin in 1945. Indeed, as officer and teacher René Charbonneau observed in 1944, Indochina’s rice production had been robust until 1943, but collapsed thereafter, in part because of transportation challenges (US bombings of rail lines and Japanese ship seizures).Footnote 6 In other words, the commitment of 900,000 tons coincided with a mounting crisis.

In addition to rice, Vichy’s governor agreed to deliver to Japan 50,000 metric tons of bauxite, 2,800 tons of zinc, 2,400 metric tons of mangrove bark, and all of the iron ore and manganese that Japan desired.Footnote 7 Vichy was not merely in a position of dependency; it was in one of near servility. French officials had but one market to which to export. Hanoi was well aware of Japanese diplomat Seiki Yano’s March 1942 declaration that Indochina should no longer expect to sell its rice at prewar prices, when Japan now had so many other rice-producing lands under its control.Footnote 8 He might have added that Indochina had no other outlet left. He could also have noted that Indochina was contributing to Japan’s war effort already, not merely with natural resources, but also with technical services (Vichy dispatched engineers to help the Japanese repair oil wells destroyed by the Dutch in Borneo).Footnote 9 A former colonial official has convincingly argued that anti-Decoux dissident Pierre Boulle’s Bridge over the River Kwai was an allegory for Decoux’s intense collaboration with Japan.Footnote 10

In theory, the 1941 agreements were meant to govern nearly all aspects of Franco-Japanese relations in wartime Indochina. In reality, however, the era was marked by constant jockeying and tensions between the two occupiers.Footnote 11 Incidents between French and Japanese were legion. Many of them centered on Japanese support for the Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo religious movements in Cochinchina. In point of fact, tensions simmered and occasionally flared through the duration of the war, from the initial Japanese testing of Indochina’s borders in 1940, to the March 9, 1945, coup. Consider the 1942 case of a Japanese consul berating the French administration for harassing Vietnamese people who were either working directly for the Japanese or doing business with them.Footnote 12

More ominous still for the French grip on power were the events that unfolded on remote Phú Quốc island in 1941. In October of that year, a Japanese force some 150 men strong landed on the island, “occupying it” to use the phrase of a French report. Their goal was to build a new airfield that could accommodate long-range bombers. In order to do so, they brought to the island some 1,700 mostly Chinese “coolies.” Only a few days after their October 14, 1941, landing, they also attempted to recruit Vietnamese laborers. The French authorities immediately complained of vexations and provocations. Government buildings were commandeered. Japanese troops allegedly threw patients out of the local clinic, and did much the same with the children of a local school. They relentlessly beat and mistreated Chinese laborers before the eyes of shocked Vietnamese and French. Japanese forces broke into the island’s radio transmission post, bound and gagged its operator, destroyed the radio material, then proceeded to rifle through the local archives. They struck the local accountant and jabbed his calves with bayonets. Vietnamese were also mistreated, many of them accused of espionage and interrogated for hours under the burning sun. In Hanoi, Vichy officials raised the matter repeatedly with Japanese representatives, and temporarily regained the upper hand. By the end of March 1942, the Japanese withdrew their forces from Phú Quốc. However, they would subsequently utilize Phú Quốc’s airfield to provide air cover for their expansion into Malaya and Burma.Footnote 13

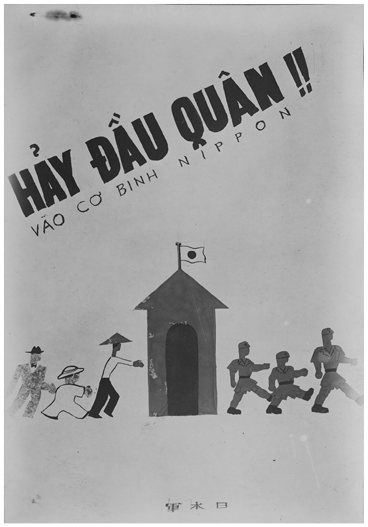

Another case of Vichy-Japanese tensions merits attention. In June 1943, a Japanese captain approached the French authorities in Nha Trang, requesting the permission to show a Japanese military recruitment film. The request was denied. And yet a pattern was emerging. That same month, Vichy’s secret services in Indochina became aware of a new Vietnamese-language recruitment poster for the Japanese imperial army (Figure 4.1). The poster showed three different Vietnamese men entering a Japanese military gatehouse: one outfitted in a conical hat, one dressed in European garb, and a third wearing the Vietnamese police helmet. They emerged from the other side dressed in Japanese uniforms. The text read “Enlist in the Japanese army!” The artist who drew the images was Munestugu Satomi, who had studied in Paris at the École des Beaux Arts. That irony was not lost on the French police.Footnote 14

Figure 4.1 A recruitment poster calling on Vietnamese to join the Japanese army.

Over the course of the next three months, Vichy’s officials became aware of Japanese schemes in Tonkin to recruit 4,000 Vietnamese mechanics to serve in the Japanese military. Some 250 northern Vietnamese had already registered, signing three-year contracts. Meanwhile, in Saigon, new Indochinese military recruits paraded in the streets wearing the uniform of the Japanese navy and infantry, eliciting “the curiosity of their compatriots.”Footnote 15 Ultimately, Vichy succeeded in having the poster removed. However, the limited recruitment of Vietnamese auxiliaries in the Japanese army and navy proceeded. Thus, while Vichy prevailed in the poster flap, it lost the broader recruitment war (even though relatively few Vietnamese ultimately enlisted). Such compromises and tensions were commonplace in this period.

Japanese authorities sought above all a peaceful, well-managed Indochina (the so-called maintenance of tranquility) from which to extract raw materials and launch their operations. “Collaboration” with Vichy was a logical extension of these two imperatives. Thus, in December 1943, the Japanese consul, Watanabe, proposed to Vichy censors the circulation of the poster featured in Figure 4.2. Typical of Japanese imperial visuals in this era, it shows female allegories of Annam, Japan, and France dancing in front of their respective national flags. Governor Decoux’s officials accepted the gist of the gesture, but still rejected the visual because they wished to see the French flag, and the French girl, centrally positioned. Here was another sign of what Chizuru Namba has termed the “latent instability” behind Vichy-Japanese coexistence in Indochina.Footnote 16

Figure 4.2 A Japanese propaganda poster from Japanese-Vichy Indochina. It reads: “The Result of Japanese-French-Indochinese Collaboration” (c. 1942).

Examples of this dynamic abound. In June 1944, a Japanese propaganda film was shown at the Olympia cinema in Hanoi. It depicted “children of greater Asia delivered from Anglo-American domination.” It trumpeted the right of Asian people to determine their own future. Little imagination was required to project these themes onto Indochina, as French censors were painfully aware. And yet the film was screened, part of a delicate balancing act with profound consequences on local nationalism.Footnote 17

Arguably the greatest test of Japanese–French relations in wartime Indochina involved the prisoner-of-war camp established by the Japanese at Xóm Chiếu, in the outskirts of Saigon. The facility held 1,800 prisoners, including Australians, British, Indians, Malaysians, and Burmese. They had been captured after the fall of Singapore, and then transferred to Indochina aboard the Japanese ship Nishin Maru in April 1942. In this matter, Vichy seems to have been especially appalled by the Japanese violation of colonial codes of racial privilege. Several documents emanating from French sources in Hanoi insisted on the fact that the Japanese were using Anglo-Australian “white troops” as “coolies.” Onlookers, colonizer and colonized alike, played a key role in this story. Even as the Commonwealth troops were being transferred into the Saigon prison camp, many Vietnamese people came to offer them biscuits and cigarettes. Several of these well-wishers were then arrested by the Japanese. Indeed, in those first days, seven Indochinese were arrested on such grounds, including an elderly man and a woman. That same month, three of them were tied to a post for an entire day in broad Saigon daylight, by way of reprisal. When local children were caught throwing cigarettes to the inmates, Japanese police traced the provider, a street cook, and proceeded to shave his head and beat him with a heated metal bar. And yet, well-wishers could not be deterred. French nationals and Chinese inhabitants of the Saigon area soon followed suit, flinging money and food over the camp walls, only to be arrested in turn.Footnote 18

Vichy duly protested the internment of prisoners on Indochinese soil, invoking both its putative neutrality and “moral” objections. Based on the context of the archival file, the latter likely involved the loss of white prestige implicit in the internment of British troops by the Japanese in an Asian colonial setting. Needless to say, both arguments fell on deaf ears. Stonewalled, Vichy officials sought to dig deeper, wondering why the prisoners could not have been posted in any other territory under Japanese control. After diplomatic channels in Tokyo yielded the implausible response that Japan had found no other place to hold the prisoners, intelligence in Saigon provided the most likely explanation. At the end of April 1942, a Japanese lieutenant at the camp revealed to a Vietnamese interlocutor: “We did not bring prisoners to Indochina merely to make them work, but rather to understand the true reactions of the French and the Vietnamese towards the British.”Footnote 19 Tokyo wished to get to the bottom of the question of whether or not Vichy was playing a double game in Asia. However, if this were the goal, then Tokyo missed the mark. If Decoux was engaging in a double game, it was a colonial one. Even a quick perusal of Indochina’s tightly controlled press reveals that Admiral Decoux’s coterie loathed the British.Footnote 20 Where the Xóm Chiếu camp proved to be a real test was in the realm of colonial race relations: French officials in Hanoi cringed at seeing whites, even British or Australian ones, dragging logs under the burning sun, under the watchful gaze of Japanese taskmasters.

Japanese–French coexistence in Indochina was thus marked by brinksmanship and tensions of all sorts. On the French side, keeping up appearances was paramount: in August 1944, Decoux issued a circular enjoining his officials to show “no weakness or sign of division” at a time when so many “foreigners” were observing Indochina.Footnote 21 However, as Chizuru Namba has noted, until March 1945, Japan served its own interests by maintaining a measure of calm in Indochina. This was especially true early on, when the area was used as a staging ground for the conquest of Malaya and the Dutch East Indies and when it provided valuable raw materials at little cost. Both sides had a vested interest in not letting conflicts escalate.Footnote 22 All of this would change after the Vichy regime was toppled in metropolitan France during the summer of 1944. Thereafter, the logic that had governed Franco-Japanese coexistence in Indochina became a charade: France was no longer the satellite of Berlin, so depicting French Indochina as an “ally” of Tokyo was increasingly impossible.

Channeling and Championing Nationalism

From his grotto at Pác Bó in 1941, Hồ Chí Minh reoriented his struggle, recasting it in the lineage of Vietnamese heroes of the past. He thereby widened his coalition, bringing noncommunist nationalists into a Việt Minh front far broader than the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP).Footnote 23 But Hồ Chí Minh was far from the only actor in Indochina who was experimenting with new nationalist configurations during the war years. Both Vichy French and Japanese leaders also stoked the embers of nationalism in Indochina.

Japan wasted little time in pointing pan-Asian-themed weapons at French rule. However, Tokyo’s ideological arsenal featured other arrows as well. On April 23, 1941, the Japan Times ran an article, castigating French rule in Indochina for having “deprived the Annamese of their language, their history, and their traditions.”Footnote 24 This was precisely the cultural project that Imperial Japan promised to undo, by offering an alternate noncolonial path to modernity.

However, many a Vietnamese nationalist who had drawn hope from the arrival of Japanese troops grew disillusioned. Consider the correspondence reaching the Japanese consul in Saigon. One letter from April 1943 pulled no punches: “If the Japanese wish to protect the Annamese, they must do so openly and topple the French, who although defeated still continue to exploit the natives in a thousand different ways, intern Indochinese who wish to join the Japanese army, and prevent coolies from studying in Japanese schools.”Footnote 25 As a Japanese official observed in August 1943, Vietnamese people watched on enviously as Japan granted independence or autonomy to the Philippines, Burma, and other former colonies.Footnote 26 And yet to further their military objectives, the Japanese were content to utilize existing European governance and mechanisms in Indochina. One example of this can be found in their refusal to advance the cause of their long-time ally Prince Cường Để.Footnote 27 Nevertheless, Japanese officials tried to play several cards, however limited their success. These included Asian brotherhood (expressed in hazy notions of a greater Asian co-prosperity sphere), anticolonialism, and professions of respect for Vietnamese traditions and culture.

To say that Vichy merely fought back would be a simplification. In fact, the “arch-Pétainist” Jean Decoux and his henchmen believed in a renaissance of their own, that of a France transformed by its defeat at the hands of Nazi Germany in June 1940.Footnote 28 Their formula for a phoenix-like rebirth was built on large doses of essentialism, and a return to a distant past of rigid hierarchies. It also involved the persecution of the same scapegoats targeted in France, especially Jews and Freemasons (both groups were dismissed from their posts in Indochina under Decoux).Footnote 29 In the cultural realm, as well, Vichy dispatched the same directives to Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam as it did to the Pyrenees and Provence. If these reductionist guidelines could serve as firewalls to Japanese schemes, all the better. As a consequence, a deluge of rediscovery rained down on wartime Indochina. Some publications vaunted national flags and national anthems. Others drew parallels between the wisdom of Confucius and that of Philippe Pétain. Not surprisingly, Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian nationalists wasted little time co-opting and redirecting this newly permissive discourse.

As a result, wartime nationalist politics in Indochina were anything but monolithic. At times, they seemed outright chaotic. For instance, in November 1942, Vichy’s military cabinet in Indochina put the final touches on a new manual to be distributed to Cambodian troops. Within military headquarters, officers debated various nationally charged symbols to be included in the instruction booklet. Including a Garuda bird would constitute a grave mistake, argued one voice, as it had been adopted by Siam as a national symbol. Why not show the Angkor-era Hanuman monkey instead? Another suggested that too great a symbolic emphasis was being placed on Franco-Cambodian entente, when Indochinese federalism also needed to be celebrated. Finally, although local particularism needed to be emphasized, were the booklet’s authors not going too far in their heavy use of the phrase “Cambodian race?”Footnote 30 In short, Vichy’s ideologues and commanders were hotly debating precisely how to manipulate, recast, and redirect identities which they considered local, but could easily be read as “national.”

One of the most astonishing attempts to channel Indochinese nationalisms can be found in the 1941 publication Hymnes et pavillons d’Indochine (Hymns and flags of Indochina). Published by the colonial authorities in Hanoi, it featured the standards, heraldry, and national anthems of France, Annam, Laos, and Cambodia. The Vietnamese anthem included the verse: “Our race has contributed to consolidate our heritage for three thousand years, from the South to the North we are all alike, we are all sons of the Hong and descendants of the Lac.” Meanwhile, the freshly invented Lao anthem featured the words: “Our race once enjoyed a great reputation in Asia, back when the Lao were united and loved one another. Today once again, the Lao have learned to love their race once more and are lining up behind their leaders.” While the French objective involved steering Lao away from the siren calls of Thailand, the nationalist message could not have been more obvious.Footnote 31

Nationalist “reawakening” took many forms. In Laos in May 1941, a committee for music was established to rekindle ancient songs. While there was mention of modernizing them, the main thrust remained preservationist. Considerable emphasis was placed on the “heritage that has been passed on to us from the time when the Lao race/nation was born.” Poetry and literature both experienced similarly channeled and carefully choreographed “revivals.” Emphasis was placed on retrieving original classics tainted by centuries of misinterpretations. In short, Vichy was fostering a return to an idealized precolonial past, while admitting the failings of French colonialism prior to 1940.Footnote 32 More than this, however, French officials were now deliberately fostering and channeling Laotian nationalism. Take a September 1942 circular drafted in Hanoi: “We must first and foremost guide Laotian patriotism … show that a nation is constituted not by tribes or villages … Rather a nation … is above all a soil fertilized by the common, unified efforts of the men who live on it.”Footnote 33

Colonial-era archives from 1943 reveal telling signs that French officials came to understand that their policies had backfired. The cultural control fires they thought they were lighting had actually contributed to fanning a nationalist blaze. Thus, in summer 1943, a Vietnamese informant told the Saigon police that “some songs such as Tran Bach Dang and Trung Tac, widely sung by youth organizations, with the blessing of the authorities, have awakened patriotic sentiment among the masses; it is natural that the Annamese be moved by them and they get goose bumps from these songs lionizing the heroes in their past.”Footnote 34

In addition to rekindling a distant past, Vichy officials in Hanoi sought to regiment and shake up Indochinese youth whom French stereotypes had long held to be “indolent.” New stadiums sprang up throughout Indochina, much ink was spilled on which sports Indochinese “races” could thrive at, and a Tour d’Indochine bicycle race was launched, reminiscent of the Tour de France. Maurice Ducoroy, whom Decoux charged with the youth and sports portfolio, made his goals clear: “progressively rendering more virile peoples long considered soft and weak.” Given that he perceived mandarins as the softest of the soft, he considered one of his crowning achievements to be an athletic competition he organized for mandarins from across Indochina in Phnom Penh in January 1945.Footnote 35 Nor, evidently, were youth the only group targeted by this athletic campaign. By 1943, most Indochinese civil servants had formed sporting associations, supported by the colonial government in Hanoi.Footnote 36

Of course, manipulation of identities and proto-fascist regimentation by Japan and France could only go so far. Profound transformations were at work within Vietnamese, Lao, and Cambodian societies during the war. For instance, as François Guillemot has shown, a potent fundamentalist nationalist strain ran through Vietnam’s right-wing nationalist currents.Footnote 37 The war years marked both an opportunity and a setback for these phalanxes that looked to Berlin for inspiration. On the one hand, the Đại Việt movement, which best embodied this strain, was swiftly dropped by Japan, and left at the mercy of Vichy reprisals as early as 1941. On the other hand, the Đại Việt members who managed to avoid this crackdown then took advantage of Vichy’s emphasis on youth sporting movements and cultural renaissance to spread their message in broad daylight.Footnote 38

However, the main thrust of the Vietnamese nationalist resurgence was not as extreme as these splinter parts of Đại Việt. What is more, this mainstream nationalist renaissance benefited from the newly permissive atmosphere fostered by Vichy’s promotion of authenticity. Decoux became the first French governor-general to use the term “Vietnam.” With Vichy’s censors now allowing the use of the word, the Vietnamese popular press needed no invitation to charge the breach. Thus, Trí Tân (New Knowledge), a mainstream periodical to which many intellectuals contributed,Footnote 39 ran a June 3, 1941, article enjoining Vietnamese people to cease referring to themselves as Annamese. In so doing, it invoked the greatness of the Vietnamese past, citing Emperor Gia Long’s exploits.Footnote 40 The very next issue castigated past renderings of Vietnamese history for having been tainted by Chinese inflections, and Western readings. It urged Vietnamese intellectuals to uncover the Vietnamese past, to reevaluate it, to visit historical sites, and to conduct oral histories with seniors.Footnote 41 The July 18, 1941, issue included an article tellingly entitled “One Needs to Know the History of One’s Country.” It derided the fact that many Vietnamese people were better versed in French history than in that of their own land. It further celebrated the “love of one’s country and national spirit.”Footnote 42 Clearly, the local past was fast becoming an instrument with which to shape a national future.

Material Change and Upheaval

Because the Indochinese economy switched trading partners completely over the course of 1941, and because of the damage wrought by Allied bombings, living conditions declined in World War II Indochina. Inflation and the colony’s payments to Japan for the billeting of troops compounded matters. The shift from a “free Yen” to the “special Yen” imposed by the Japanese in 1942 also contributed to this downward spiral. As a result, the cost of living for an Indochinese worker grew nearly sixfold between 1940 and 1944.Footnote 43 In their private letters, Indochinese correspondents complained about how expensive everything had become.Footnote 44

Japan could not furnish Indochina with all of the finished goods it required, and after 1941 autarky spurred new forms of local production. Indeed, in 1942 Vichy officials in Hanoi tried to negotiate not just the price of the rice they were exporting to Japan, but also the quantities of finished goods they were receiving; talks proved arduous.Footnote 45 However, quotas were seldom actually met, and Indochina endured shortages in many areas.Footnote 46 As a result, textiles were increasingly produced in Indochina itself, rather than being imported. Because of shortages of cement, ersatz materials were used at construction sites in Hanoi.Footnote 47 Fish and peanut substitutes were found for fuel.Footnote 48 And yet, despite this accrued local production and resourcefulness, all of the other factors just examined – disrupted avenues of communications, lack of trading partners, etc. – meant that the Indochinese economy stood on the brink of collapse by 1944.Footnote 49

The Case of the Indochinese Residing in France

The Indochinese population in France in 1940 included many soldiers and workers brought there to wage economic and military warfare. After France fell to Germany in June 1940, the fate of these mostly Vietnamese subjects became a source of acrimony. At Paris’s Lycée Henri IV, teacher Jean Guéhenno observed in passing the number of young Vietnamese people he saw signing up in German ranks.Footnote 50 No doubt they seized the opportunity of France’s defeat. But was this merely a matter of making a friend out of an enemy’s enemy? A few weeks after the Allied landings in Normandy, General de Gaulle’s Free French issued a report on Indochinese workers who had been recruited by the Germans to build fortifications as part of Operation Todt. The document mentioned that some fifty Vietnamese were training to join the Wehmarcht. Another source evoked a German office near the Eiffel Tower, devoted to recruiting both soldiers and workers.Footnote 51

In intellectual milieus as well, fascism held a certain appeal. Charles Keith has traced the contorted political itinerary of men like Đỗ Đức Hồ, who emerged as passionately anticommunist. Đỗ Đức Hồ wished to graft the canonical right-wing nationalism of Maurice Barrès and Charles Maurras onto Vietnam. He soon became enamored of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and with the notion of an independent Vietnam allied to Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany. He even asked the Japanese to send him back to Indochina, which they refused to do, granting only his request to found an institution in France devoted to pan-Asian “friendship.”Footnote 52 In this respect, his choices may have been inspired by, or at least bear some parallels with, Indian nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose, who allied himself with Japan and Germany and raised an army for his cause.

Of course, the vast majority of Indochinese subjects in France did not take this route. Lê Hữu Tho’s memoirs recount his wartime years as part of the Main d’oeuvre indigène (MOI), a government labor agency. He explains that some 20,000 Vietnamese were working as part of this organization in mainland France in June 1940, but that roughly 4,000 of them were sent back to Indochina in the early days of the Vichy regime, leaving around 15,000 MOI Indochinese workers in France for the duration of the war. Many initially toiled in munitions factories, before France’s defeat in June 1940; thereafter they were redirected to farm, road, mechanical, or forest work. Pierre Daum estimates that 95% of these workers had been enlisted in Indochina “against their will.” In French factories, and in fields, Vietnamese laborers worked for a fraction of the pay earned by their French colleagues. Furthermore, many Vietnamese forged friendships and struck up romances with local French women, which unnerved colonial officials, because they challenged colonial hierarchies. Experiences in this community varied widely. David Smith has found that 7% of the Vietnamese population in France in World War II were at some point arrested by Vichy, mostly for stealing food. Additionally, some were outsourced to the Germans for construction projects. Others, like Lê Hữu Thọ, were arrested by the Germans.Footnote 53

The March 9, 1945, Coup

In Indochina, everything changed on March 9, 1945, when a surprise Japanese coup toppled French rule. One French account explains: “The facts are brutal: in a few hours, over the course of a few days, the French army was completely eliminated, massacred, taken prisoner, or driven out of Indochina.”Footnote 54 Although a handful of French nationals were retained in technical posts, the vast majority were interned.

In 1948, looking back on the troubled year 1945, Dr. Marcel-Louis Terrisse, the long-time director of indigenous health (AMI) in Annam, recalled the unique features of “concentration life” in Hue. Although he was never personally threatened, he had endured internment first by the Japanese, then by the Chinese, and finally by the Việt Minh.Footnote 55 He claimed that his Vietnamese patients never altered their attitude toward him, but even he recognized the palpable shift in power relations. Those who until recently had been carried around in rickshaws were now lumped together in prison camps and specially marked quarters.Footnote 56

The March 9, 1945, Japanese coup de main occurred nearly a year after Vichy ceased existing in the metropole. This has led some to wonder why Japan waited as long as it did. No doubt Imperial Japan was already obtaining what it wanted from Vichy cooperation at limited cost. But then why the change of heart in March? American air attacks in January 1945 had reinforced Japanese suspicion that the United States might be planning landings in Indochina. Conspiracy theories abound around March 9, 1945. A French novelist-cum-historian has suggested that word got out in the mainland French press before it even happened, thereby implying collusion.Footnote 57

In any event, on location the surprise was total. Many French nationals were left stranded in a movie theater in downtown Hanoi watching another colonial parable, Tarzan, as the coup unfolded.Footnote 58 None saw it coming. Georges Jacquinot offers an interesting example. His personal papers show that he spent the war years relatively comfortably: his Hanoi Cercle Sportif (athletic club) membership was issued in July 1942. The file also includes an intriguing conversion table designed for the French to read the insignia, ranks, and uniforms of the Japanese army. Finally, it contains the programs of Japanese plays performed at Hanoi’s municipal theater in November 1940. All of this suggests that Hanoi’s colonial society had lived in a bubble and had established cordial relations with the Japanese. The bubble burst on March 9 as Jacquinot rose from the dinner table to the sound of gunfire. He tried to reach the citadel, where resistance was being organized. As he caught his breath in front of the Splendide Hotel, a detachment of Japanese troops arrived and secured the quarters, driving Jacquinot indoors.Footnote 59 Shortly thereafter, Japanese forces entered the hotel and arrested all Europeans, seizing their arms. French colonialism had crumbled in a matter of hours.

Over the coming months, in Saigon, Vietnamese lawyers opted to work in Vietnamese, rather than French. Throughout Vietnam, French place-names were replaced by Vietnamese ones. The names of Vietnamese military heroes of the past replaced Garnier, Ferry, and Joffre streets. In Huế, authorities under the leadership of Emperor Bảo Đại tried to wrestle the everyday management of Vietnam from the Japanese. In the press, colonialism was decried, and the future hotly debated. On the initiative of Tokyo, a new school for bureaucrats was founded in Hanoi.Footnote 60

Meanwhile, in Phnom Penh, King Norodom Sihanouk (handpicked by Decoux in 1941) declared Cambodia’s independence on March 13. The country was henceforth called Kampuchea. The Buddhist lunar calendar was reimplemented, at the expense of its Western counterpart. All accords guaranteeing French tutelage were now null and void. Cambodia would operate within the framework of the Japanese co-prosperity sphere.Footnote 61

In Laos, the king of Luang Prabang declared independence on April 8, 1945. He called Japan a “trusted ally” and vowed to operate within the co-prosperity sphere. In August, after Japan’s surrender, the king would warn liberated French people in Laos that the clock could not be turned back: the war might be over, but Laos’s April 1945 independence was not negotiable.Footnote 62

The Hours of Independence

One of the particularities of the Indochinese context has to do with the double proclamations of independence that took place in March, then in August 1945. The first followed the abrupt overturning of French rule by the Japanese on March 9, the second the surrender of Japan after the atomic blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The period from March to August 1945 was one of rapid change. Bảo Đại declared Annam and Tonkin to be independent. In April, he formed a new Vietnamese government led by Trần Trọng Kim. His ministers were, according to Vũ Ngự Chiêu, “a team of modern professionals” comprised of lawyers, teachers, and doctors, many of whom had been tempted early on by collaboration with Japan. They swiftly undertook meaningful reforms. Vietnamese replaced French in the administration and in the classroom. Public assemblies, including protests, that had long been curtailed under French rule, were now permitted. Although later dismissed by the Vietnamese communists and French alike – the latter spoke of a “gouvernement de fait” – the short-lived Trần Trọng Kim era was undoubtedly significant. It cemented Vietnamese national unity, both constitutionally and territorially, and saw a re-energizing of youth movements and of the political scene more generally. However, in the end, the challenges it faced proved overwhelming. For instance, in July 1944, Vũ Ngọc Anh, Kim’s minister of health, was killed during an Allied air raid. Mostly, Trần Trọng Kim’s government was tributary to Japan’s military presence. Public opinion also connected it to the disintegration of Vietnam’s economy. Despite many attempts to create relief organizations, the terrible famine in the North exacted a dreadful toll.Footnote 63

When Japan surrendered unconditionally in August 1945, the opportune moment presented itself to the Việt Minh. We should, however, be careful when framing this takeover historically. Christopher Goscha reminds us that there was nothing foreordained about the outcome of the August 1945 revolution: after all, at the time the Communist Party only counted some 5,000 members, some half of them incarcerated.Footnote 64 The seismic shifts brought about by World War II certainly had multiple consequences, but they hardly propelled Hồ Chí Minh to power, deus ex machina. The ICP’s uprisings in Cochinchina had been roundly crushed by Vichy’s police and military in 1940, with executions of participants in these rebellions continuing through 1941. In the South, especially, the ICP had been outright “decapitated.” Given that the Việt Minh was staging war against both Vichy and Japan, few signs seemed to presage its seizure of power in August 1945.Footnote 65 Indeed, in August 1945, some at the heart of the organization still fretted that the Việt Minh had not learned the errors of 1940 – which is to say that they should avoid rash action when presented with a power vacuum.Footnote 66 Orders issued by the ICP reveal a measure of confusion and hesitation as well, at a time, moreover, when Hồ Chí Minh himself was recovering from a serious illness. Improvisation proved key in August 1945. A frontal attack on Japanese forces was only narrowly avoided, and a way of seizing power without confronting the Japanese was ultimately devised.Footnote 67 The August 1945 Revolution flowered from a cracking Japanese foundation, but its ultimate outcome had more to do with contingency and the discredit suddenly heaped on those perceived to have collaborated with Japan.

In Cambodia, meanwhile, independence was celebrated for the second time in under a year. An August 1945 report held in the Cambodian national archives – still drafted in French – recounted the “grandiose” celebrations that took place in Kompong-Chnang on August 26, 1945. Thousands of Cambodians, as well as Vietnamese and Chinese “delegations,” were said to have participated in the event. Two young men holding the Cambodian national flag led a procession roughly half a mile (1 kilometer) long. A large banner read “Long live independent Kampuchea!” A row of national guards blared their horns. Yuvan youth groups, established under Vichy rule, paraded. A public official delivered a speech built on three pillars: Kampuchea’s independence, the role of the monarchy, and Buddhism.Footnote 68

The Future of Indochina

In 1941, as he sailed from Indochina to the United States en route to joining General de Gaulle’s ranks, Hanoi teacher Pierre Laurin mused over the future of the colony he had just left. He articulated his thoughts around three main points. First, the language of liberation, democracy, and justice deployed by the anti-Axis forces spelled the inevitable advent of decolonization, he opined. Second, Indochinese nationalism had matured, around intellectuals he himself had trained, into a multidirectional and potent force. The genie could not be put back into the bottle. This new generation of nationalists, whom some called communists (Laurin refused to), many of whom he had personally taught at the Lycée Albert Sarraut, rejected the mandarin system that the French had not only left in place but actually bolstered. Third, the Vietnamese could not be held in check much longer. They faced a glass ceiling in Indochina’s various bureaucracies; a mere trip to Siam or the Philippines could open their eyes to high-ranking Asians in position of power. Japan’s emancipatory discourse achieved much the same effect. In short, Laurin predicted, Vietnamese independence would happen one way or another: either with France’s approval or against it. Perhaps French Indochina’s federalism could be morphed into a US-inspired structure, in which France might retain a role, he wondered?Footnote 69

Such notions of maintaining France’s relevance in Southeast Asia would prove enduring. By 1946, in France, colonial reformers (many of them, like Henri Laurentie, having occupied important positions in the colonial administration of de Gaulle’s Free French, Vichy’s imperial rival) were beginning to chart new paths in which empire would make way for a “union” and colonies would eventually be replaced by “associated states.” In Indochina, they revived earlier schemes for a vast federation; to some these plans were earnest, to others they mostly involved ways of countering Việt Minh influence.Footnote 70 However, fundamentally, even these more enlightened officials failed to recognize the fact that, across Indochina, such attempts at reform were backward-looking, insofar as independence had already been declared – twice – in 1945.

Conclusion

We have seen that straight lines cannot be drawn even in the immediate buildup to the August 1945 revolution. This said, the war years clearly acted as a catalyst. For instance, there can be no doubt that the Japanese and Vichy – as well as the competition between them – fostered (sometimes unwittingly) a fertile terrain for nationalists and revolutionaries. Japanese and Vichy policies, combined with Allied bombings, also conspired to create the conditions for famine. The March 1945 coup started a chain of events that brought about not one but multiple declarations of independence, what some might call an acceleration of history. The ramifications of the war years would also bear fruit later on, some of it bitter. King Sihanouk of Cambodia, who would traverse the twentieth century, was a Decoux pick. More ominously, several historians have suggested that some remnants of Vichy’s essentialist ethos, especially its quest to “return to the soil,” would continue to shape that nation, including its murderous leader Pol Pot, long afterward.Footnote 71 In Vietnam, some Vichy-era nationalist formulae would resurface, albeit in transposed form, during the long years of division and war between North and South Vietnam. Just as the Vichy period lurked for a long while, sometimes unacknowledged, in the collective memory of metropolitan France, so, too, would the wartime era shape the post–1945 politics of all the countries of Indochina.