1 Introduction

Cognitive distortions have been identified in the research literature as a key contributing factor to the instigation and maintenance of problem gambling (Ladouceur et al., Reference Ladouceur, Sylvain, Boutin and Doucet2002; Sharpe, Reference Sharpe2002). Numerous studies have shown that gamblers hold irrational beliefs and suffer from cognitive biases such as the illusion of control, the gambler’s fallacy, and the attribution bias, which lead to inaccurate inferences about outcome probabilities (Delfabbro & Winefield, Reference Delfabbro and Winefield2000; Gaboury & Ladouceur, Reference Gaboury and Ladouceur1989; Sundali & Croson, Reference Sundali and Croson2006; Toneatto et al., Reference Toneatto, Blitz-Miller, Calderwook, Dragonetti and Tsanos1997). The resulting overestimation of the chances to win and the underestimation of possible losses propel individuals to place more risky bets and encourage persistent gambling.

Besides erroneous beliefs about probabilities, gambling persistence and risk taking may also be affected by the anticipation of emotions associated with gambling outcomes. The role of anticipated emotions is well documented in the literature on decision making, with anticipated regret receiving particular attention (Mellers et al., Reference Mellers, Ritov and Schwartz1999; Zeelenberg et al., Reference Zeelenberg, van Dijk, Manstead and van der Pligt2000). However, relatively few studies have examined anticipated regret in the context of gambling. Wolfson and Briggs (Reference Wolfson and Briggs2002) investigated the intentions of 485 lottery players to participate in a newly introduced lottery in the United Kingdom and found that 38% were willing to purchase tickets because they anticipated feeling regret if their numbers came up. This share increased to 54% for those who played regularly with the same set of numbers.

In a comprehensive study of the Dutch postcode lottery, Zeelenberg and Pieters (Reference Zeelenberg and Pieters2004) showed that the regret people expected to feel if they decided not to play and discovered that their neighbor had won significantly contributed to their intention to participate in the lottery in the near future. Rae and Haw (Reference Rae and Haw2005) assessed the effects of anticipated regret, disappointment, and elation, on the persistence in gambling of 93 gamblers and found that anticipated emotions did not predict gambling persistence. Although all three studies examine the relationship between anticipated regret and gambling, their results do not allow to draw conclusions about the clinical implications of regret for excessive gambling. This is due to the fact that none of the studies screened the participants for gambling problems making it impossible to assess how many of them actually met the criteria for problem or pathological gamblers.

The present study examined the role of anticipated regret in problem gambling by focusing on two issues. First, it estimated the effect of gambling preference on the anticipation of regret. Previous research has suggested that although erroneous beliefs and distorted cognitions are common among all types of gamblers, pathological gamblers seem to suffer more cognitive illusions (Baboushkin et al., Reference Baboushkin, Hardoon, Derevensky and Gupta2001), endorse more irrational beliefs (Joukhador et al., Reference Joukhador, Maccallum and Blaszczynski2003) and to be more convinced in their irrational beliefs than social gamblers (Ladouceur, Reference Ladouceur2004). In a recent study, Tochkov (Reference Tochkov2009) showed that high-frequency gamblers were less able to anticipate regret than low-frequency gamblers indicating that inaccurately anticipated regret is a possible contributing factor to persistent gambling. Participants were asked to choose gambles with fictitious monetary outcomes and imagine how they would feel once they learn the outcome of their decision. A week later, the same participants were asked to play the same gambles for real with actual monetary wins and losses and rate their regret. Tochkov (Reference Tochkov2009) reported that the difference between anticipated and actual regret was significantly larger for high-frequency gamblers as compared to that of low-frequency gamblers.

These findings suggest that when gamblers do not anticipate the negative feelings of regret they might experience once they learn the outcome of their bet, they are more tempted to continue gambling. In contrast, the anticipation of regret about gambling outcomes could serve as a natural inhibitor to continuous gambling. This line of reasoning is supported by evidence from a number of studies which found that the anticipation of regret decreases the intentions of engaging in risky and potentially addictive behaviors (Richard et al., Reference Richard, van der Pligt and de Varies1996; Van Empelen et al., Reference Van Empelen, Kok, Jansen and Hoebe2001). In a recent study, Fernandez-Duque and Landers (Reference Fernandez-Duque and Landers2008) showed that individuals experienced more regret than they had anticipated, which in turn made them more risk averse in a subsequent gambling task.

The present study explores the relationship between anticipation of regret and gambling preferences by giving gamblers the choice between two gambles, one of which promised to reveal the outcome of the selected option only (partial feedback) and the other the outcome of both the selected and the rejected options (complete feedback). It was hypothesized that a stronger gambling preference would be adversely associated with regret anticipation and would thus result in the more frequent choice of the gamble with partial feedback.

The second goal of the study was to assess the effect of gambling preferences on risk attitudes. Previous studies have demonstrated that problem gamblers exhibit higher degrees of risk taking than normal subjects because they suffer from cognitive biases that make risky bets more attractive (Gaboury & Ladouceur, Reference Gaboury and Ladouceur1989; Toneatto, Reference Toneatto1999) or because they feel overconfident in their skills (Goodie, Reference Goodie2005). Accordingly, it was hypothesized that the risk attitude associated with a stronger gambling preference would be skewed towards risk seeking due to lower levels of regret anticipation. Following Zeelenberg et al. (Reference Zeelenberg, Beattie, van der Pligt and de Vries1996), two experimental conditions were created, each of which contained a partial and a complete feedback option. In the risky feedback condition, partial feedback was associated with the risky gamble, whereas in the safe feedback condition the regret-minimizing option was the safe gamble. I hypothesized that a weaker gambling preference would trigger regret avoidance and thus a preference for the partial feedback which would lead to risk seeking or risk aversion depending on the feedback condition. In contrast, a stronger gambling preference would be related to risk seeking regardless of the expected feedback. Moreover, I examined risk preferences for gambles with low and high variation in outcome probabilities to test for the robustness of the results with respect to the different stakes involved in winning and losing.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

Participants (n=108) were undergraduate psychology students who responded to a recruiting message seeking individuals who like to gamble. Sixty-two of the participants (57%) were female, and 46 (43%) were male. The majority (85%) were between the ages 18–25, 10% were between 26–30, and 5% were older than 30.

2.2 Measures

The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesieur & Blume, Reference Lesieur and Blume1987) was used to assess the extent of gambling problems and preferences. The SOGS is a 20-item questionnaire based on the DSM-III criteria for pathological gambling and is one of the most widely used measures in studies on gambling for both clinical and non-clinical populations. It has well-established psychometric properties, including high internal reliability and a 1-month test-retest reliability. SOGS scores range from 0 to 20, with a score below 3 indicating no gambling problems, a score of 3 or 4 indicating a problem gambler, and a score of 5 or higher suggesting a probable pathological gambler. For the purposes of the current study, participants with a SOGS score of 1 or 2 were classified as social gamblers, and those with scores of 3 and higher as problem gamblers. Higher levels of gambling preference were expected to be negatively associated with regret anticipation and to contribute to more risk seeking.

The Gambling Attitudes and Beliefs Survey (GABS; Breen & Zuckerman, Reference Breen and Zuckerman1999) was used to evaluate cognitive biases, irrational beliefs, and positive values regarding gambling. It consists of 35 items including statements such as “If I have been lucky lately, I should press my bets” or “People who make big bets can be very sexy.” Responses are recorded on a 4-point Likert-type scale. High scores on GABS suggest that participants view gambling as exciting and socially meaningful, and that luck and strategies (even illusory ones) are important, which in turn was hypothesized to impede the feelings of regret and regret anticipation and encourage risk taking.

The Competitiveness Index — Revised (CI-R; Houston et al., Reference Houston, Harris, McIntire and Francis2002) is a 14-item measure designed to assess the desire to win in interpersonal situations. Respondents rate the extent to which they agree with the items using a 5-point Likert scale. Competitiveness as measured by the CI-R has been shown to be an important risk factor for pathological gambling (Parke et al., Reference Parke, Griffiths and Irwing2004), and was thus hypothesized to encourage risk seeking.

The Eysenck Impulsiveness Questionnaire (EIQ; Eysenck et al., Reference Eysenck, Pearson, Easting and Allsopp1985) is a 63-item measure with 3 subscales targeting different aspects of impulsivity. Only the first two subscales focusing on impulsiveness and venturesomeness were used as it was assumed that these traits affect the risk preference of participants. The responses of the two subscales were combined into one measure with each given equal weight. Impulsivity is a common trait of problem gamblers and was expected to result in more risk taking as it impedes the assessment of anticipated emotions and probabilities.

2.3 Computerized gambling task

The task involved 20 pairs of gambles displayed on a computer screen in a sequence randomized separately for each subject. Each gamble had two possible payoffs with different probabilities. Probabilities were either .3 and .7 (low variance) or .1 and .9 (high variance). Within each pair of gambles, only gambles with the same variance were included in order to examine whether variation in the probability of a payoff across gambling pairs affected risk preference. Each pair of gambles included one relatively safe (small payoff with high probability) and one risky gamble (high payoff with low probability).Footnote 1 Possible monetary outcomes involved wins and losses ranging between $0 and $15 and were designed so that when gambles were paired they would have the same expected value. Each gamble displayed on the screen was represented by a pie chart, which visualized the different probabilities. Payoffs and their corresponding probabilities were also shown beneath each gamble, along with a message informing participants that they would learn only the outcome of their chosen gamble or the outcome of both gambles, depending on whether the gamble was associated with partial or complete feedback, respectively.

2.4 Feedback conditions

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions designed by Zeelenberg et al. (Reference Zeelenberg, Beattie, van der Pligt and de Vries1996). In the risky feedback condition participants learned the outcome of the risky gamble regardless of whether they preferred the safe or the risky gamble. In contrast, the outcome of the safe gamble was revealed only if it was the preferred one. The partial feedback on the risky gamble thus ensured that regret was not possible, whereas the complete feedback associated with the choice of the safe gamble guaranteed that regret was felt given the possibility of comparing the outcomes of the two gambles. In the safe feedback condition, it was the outcome of the safe gamble that was disclosed regardless of the choice of gamble. On the other hand, participants learned the outcomes of both gambles only if they preferred the risky gamble. In this condition, only the choice of the risky gamble could result in regret as it was associated with complete feedback.

2.5 Procedure

Participants were told that the experiment involved choices between pairs of gambles with real monetary wins and losses and that their payment would be the sum of their earnings over all trials. After providing informed consent, participants were randomly assigned either to the risky or the safe feedback condition and were asked to complete the questionnaire package including SOGS, GABS, CI-R, and EIQ. Next, they were presented with the computerized gambling task. The experimenter demonstrated how to play the gambles on the computer and informed them about the partial and complete feedback associated with each gamble. Participants were told that in each trial they should chose one gamble and then rate the strength of their preference for that gamble on a scale of 1 (very weak preference) to 12 (very strong preference). The experiment lasted approximately 45 minutes and everyone was paid $10 regardless of their actual winnings. Lastly, participants were debriefed about the purpose of the experiment and the actual likelihood of winning, and were provided with information on where to seek help with gambling problems if needed.

2.6 Data analysis overview

The data were analyzed using linear regression. The dependent variable was the strength of risk preference and was modeled after Zeelenberg et al. (Reference Zeelenberg, Beattie, van der Pligt and de Vries1996) by converting the preference scores for the selected gambles to a scale evenly spaced around zero. For this purpose the preference scores were multiplied by 1 for the risky gamble and −1 for the safe gamble and then 1/2 was subtracted to create a scale that is evenly spaced around zero. The risk preference variable thus ranged from −11.5 (strong risk aversion) to 11.5 (extreme risk seeking). The independent variables included the strength of gambling preference as measured by the SOGS score and feedback condition (safe vs. risky feedback). The interaction between strength of gambling preference and feedback condition was included in the regression equation along with additional control variables such as competitiveness, impulsivity, gender, and the level of gambling biases and distortions concerning gambling (as measured by GABS). Lastly, a lag variable was introduced to estimate the effect of the risk preference indicated on the previous trial.

3 Results

Descriptive statistics of the sample are displayed in Table 1. Out of a total sample of 108 participants, 66% were classified as social gamblers (1≤SOGS≤2) and 34% as problem gamblers (SOGS≥3). To test for differences in the anticipation of regret, I examined the choices made by social and problem gamblers in each of the two feedback conditions. To avoid regret, participants were expected to choose the safe gamble in the safe feedback condition and the risky gamble in the risky feedback condition. In the risky feedback condition, the risky gamble was the preferred option by both types of gamblers with about two thirds of all gambles. Although this share was higher for problem gamblers as compared to social gamblers (66.3 vs. 64.7), the difference was not statistically significant. In the safe feedback condition, the safe gamble was chosen more often than the risky gamble for both categories of gamblers. Again, the share of risky gambles selected by problem gamblers was higher than for social gamblers (47.2 vs. 41.6), however this time the difference was statistically significant (p<.05). Furthermore, in the safe feedback condition the difference between the shares of safe and risky gambles for social gamblers was significantly larger (p<.001) than for problem gamblers, indicating that problem gamblers are less sensitive to the effects of anticipated regret.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of the entire sample and by gambler type

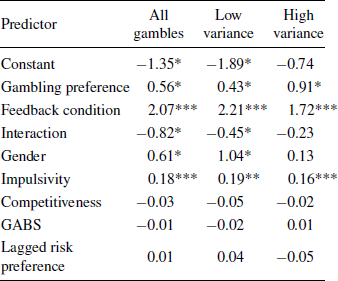

The results of the regression analysis examining the effect of gambling preference on risk attitudes are shown in the first column of Table 2. The constant represented the average risk preference in the safe feedback condition and was statistically significant. The negative sign of the coefficient indicated that participants exhibited risk aversion in the safe feedback condition. The feedback variable which had also a significant coefficient denoted the difference in the levels of risk preference between the two feedback conditions. The sum of the feedback coefficient and the constant indicated the presence of risk seeking in the risky feedback condition.

Table 2: Results of the multiple regression analysis for variables predicting risk preference

* p<0.05

** p<0.01

*** p<0.001

The gambling preference variable measured the marginal effect of SOGS scores on risk preference. In the safe feedback condition an increase in the SOGS score by one led to an increase in risk seeking by 0.56. The interaction between gambling preference and feedback condition represented the additional marginal effect in the risky feedback condition. Accordingly, a one point increase in the SOGS score resulted in a 0.26 (0.56–0.82) points decrease in risk seeking (or alternatively increase in risk aversion). Higher SOGS scores were correlated with risk seeking in the safe feedback and risk aversion in the risky feedback. This is the opposite of what should be expected if regret minimization was a primary concern. These findings suggest that individuals with a stronger gambling preference are less susceptible to the effects of anticipated regret. Among the control variables, only gender and impulsivity showed a significant and positive effect suggesting that higher levels of impulsivity and being male contribute to more risk seeking.

The estimation was also performed separately for gamble pairs with a relatively low (.3 vs. .7) and a relatively high (.1 vs. .9) variation in outcome probabilities to test whether an increase in the riskiness of gambles affected regret minimization. The estimates are shown in the second and third column of Table 2, respectively. In the low-variance model the statistical significance and the signs of the coefficients were largely identical to the estimates of the model that included all gambles. The only exception was that the magnitude of the decrease in risk preference in the risky feedback condition was much smaller as compared to the overall model. In the high-variance model participants did not exhibit a significant risk aversion in the safe feedback condition. Moreover, the effect of gambling preference on risk attitudes did not differ significantly across the two feedback conditions, suggesting that higher SOGS scores were associated with increases in risk seeking regardless of the possibility to experience regret.

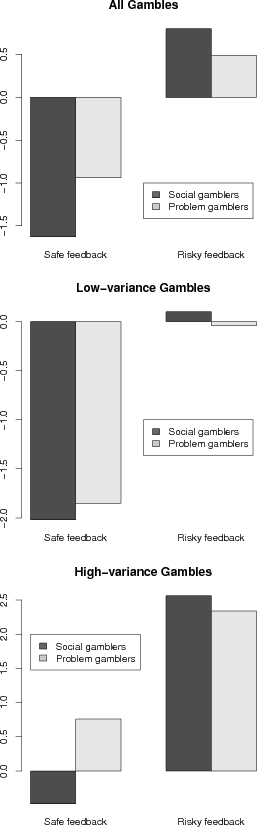

Figure 1 illustrates the average risk preference levels for each of the four experimental groups. In the model including all gambles, risk preferences for the two groups of gamblers had the same direction within each feedback condition: risk aversion in the safe feedback condition and risk seeking in the risky feedback condition. However, the gap between the mean levels of risk aversion exhibited by social (M=−1.63) and problem gamblers (M=−0.94) in the safe feedback condition was statistically significant. Similarly, the magnitude of risk seeking in the risky feedback condition differed significantly between social (M=0.80) and problem (M=0.49) gamblers.

Figure 1: Mean levels of risk preference for social and problem gamblers in the two feedback conditions.

In the high and low variance models, social gamblers continued with their pattern of risk aversion in the safe feedback and risk seeking in the risky feedback condition, however the magnitude of risk aversion was much stronger in the low variance model (M=−2.02 vs. M=−0.48) and the risk seeking was much more intense when there was a large variation in outcome probabilities (M=2.56 vs. M=0.10). By comparison, problem gamblers exhibited risk aversion in the low variance model and risk seeking in the high variance model regardless of the feedback condition.

4 Discussion

Previous research has suggested that anticipated regret is important in decision making. This study investigated the role of anticipated regret in problem gambling, arguing that it might be a contributing factor to excess gambling and risk taking. It found a negative correlation between the strength of gambling preferences and regret anticipation. Weaker gambling preference was associated with the choice of the safe gamble in the safe feedback condition and the risky gamble in risky feedback condition, suggesting that those with less gambling problems anticipated regret as they selected the regret-minimizing alternative. Such behavior is consistent with the findings of Zeelenberg et al. (Reference Zeelenberg, Beattie, van der Pligt and de Vries1996) and Ritov (Reference Ritov1996).

In contrast, stronger gambling preference led to risky gambles being chosen more often regardless of the feedback condition. Furthermore, despite the higher share of safe gambles in the safe feedback condition, the difference between the two types of gambles was not statistically significant for those exhibiting stronger gambling preference. These findings suggest that complete feedback and the resulting threat of experiencing regret did not lead to the adoption of a regret-minimizing strategy across the two experimental conditions for individuals with more gambling problems, and did not deter them from seeking out the risky gamble more often than individuals with a weaker gambling preference.

Given that stronger gambling preference was associated with less responsiveness to possible regret, it seems that weak anticipation of negative emotions might fuel excessive gambling. Although future research needs to shed more light on this issue, it is possible that the expectation of experiencing a negative emotion such as regret over losing the next round of betting can serve as a natural inhibitor to prolonged gambling. Hills et al. (Reference Hills, Hill, Mamone and Dickerson2001) showed for instance that current negative mood did in fact result in shorter gambling sessions for non-pathological gamblers. In contrast, the failure to take into account the possibility of dealing with an unpleasant emotion after the outcome of the bet has been revealed could amplify the lack of self control and result in excessive gambling.

The second hypothesis of this study, which addressed the link between the strength of gambling preference and risk taking was also supported by the findings. Higher levels of gambling preference were associated with risk seeking in the safe feedback condition and risk aversion in the risky feedback condition. This indicates that the failure to identify the regret-minimizing option has an adverse effect on risk taking behavior. Moreover, when the difference in probabilities of gambling outcomes increased, magnifying the chances of experiencing losses and thus feeling regret, stronger gambling preference tended to result in risk seeking regardless of the feedback condition.

One of the limitations of the study is that it used students rather than community gamblers which weakens the applicability of the results to the population of pathological gamblers. A second limitation was that the study was not able to determine whether problem gamblers were less able to anticipate regret than social gamblers or whether they simply experienced less regret. Although previous studies have shown that it is the inaccurate anticipation of regret (Tochkov, Reference Tochkov2009), more research is needed to examine this issue in more detail. Despite these limitations, the findings of the study could have important implications for the clinical practice as it is likely that weaker anticipation of regret affects gambling behavior in combination with other cognitive distortions. Cognitive treatments for pathological gamblers have focused on challenging the irrational beliefs and faulty cognitions involved in gambling fallacies and providing educational advice on the nature of randomness and probabilities (Ferland et al., Reference Ferland, Ladouceur and Vitaro2002; Ladouceur et al. Reference Ladouceur, Sylvain, Boutin, Lachance, Doucet and Leblond2001, Reference Ladouceur, Sylvain, Boutin, Lachance, Doucet and Leblond2003). A better anticipation of negative emotions could be promoted in a similar framework by identifying, challenging, and correcting faulty perceptions about negative emotions associated with the outcomes of gambles. In particular, the salience of regret needs to be increased whereby the therapist would for instance depict the possible consequences of excessive gambling by describing the financial and social issues involved. The goal of this technique would be to teach patients to focus on a more realistic assessment of the consequences of their behavior and the concomitant negative feelings including regret before making the decision to continue gambling.

This approach needs to be studied in more detail in the future given the ambiguities in the literature. While some studies have shown that a better grasp of probabilities and common fallacies reduces risky behavior in gambling (Floyd et al., Reference Floyd, Whelan and Meyers2006), others have found that it does not translate into decreases in actual gambling behavior (Williams & Connolly, Reference Williams and Connolly2006). Similarly, increasing the salience of the negative emotions associated with risky behavior was reported to be effective in reducing risk taking in sexual behavior (Richard et al., Reference Richard, van der Pligt and de Varies1996), whereas the same technique improved the anticipation of regret over heavy drinking but did not result in less drinking or less risk taking (Murgraff et al., Reference Murgraff, McDermott, White and Phillips1999).