INTRODUCTION

On 10 August 1851, in Moulmein, the capital of British Burma, a gang of one hundred Indian convicts was engaged in its routine monthly task of loading coal onto the East India Company's paddle steamer HC Tenasserim, at the docks of Mopoon. This ship was one of many that plied the Company's trading routes around the Bay of Bengal, connecting port cities in South and South East Asia.Footnote 1 Like other Company steamers, the HC Tenasserim carried a diverse cargo. This included men, women, and children – Company officials with their families and servants, merchants and traders, military officers and troops, and labourers – and trade goods like cotton, spices, pepper, opium, and betel nut. In common with other such vessels, the Tenasserim also routinely conveyed Indian transportation convicts into sentences of penal labour. Port cities like Moulmein, one such carceral site, were key locations through and in which the Company repressed and put to work colonized populations. They were places in which convicts joined other colonial workers in the formation of a remarkably cosmopolitan labour force.

The Moulmein convicts working in the docks of Mapoon had, in the early hours of the day, marched the three miles between their jail and the coal shed wharf. The deputy jailer, Mr Edwards, with twenty-six guards, had supervised their work, with a half dozen armed reserve stationed a short distance away. As usual, the convicts were close to finishing the task by the early afternoon. But this was no ordinary day in Moulmein. Just as they were finishing loading the boat, nineteen of the convicts grabbed three of the lascars (sailors) who were holding the ropes tethering the ship to the riverbank and threw them overboard. Their guards approached, but other convicts kept them back by pelting them with lumps of coal. The rest let go of the ropes and pushed the boat off. With Moulmein sitting at the southern confluence of the point at which the Salween River splits into four, they set sail north towards Martaban and got behind their oars, with both the wind and the flood tide in their favour. If port cities were places of convict repression and coerced labour, they were also always potential spaces of collective rebellion. Immediately, deputy jailer Edwards ordered a party to set off along the river in pursuit of the convicts. It quickly caught them up, for the coal boat was heavy, and managed to board the steamer and recapture the men. Despite the convicts’ capitulation, the reaction of the guards was brutal. They killed three men, and wounded eleven, who suffered dreadful and multiple injuries, including sabre wounds, fractured skulls, and broken legs.Footnote 2

The convicts’ transportation to Burma, their work at the coal shed, their collective act of resistance, and the extreme violence countered against it raise key themes with respect to Asian convict workers. This article will explore the origins of Indian penal transportation in the context of earlier and concurrent metropolitan practice in Britain's Atlantic world and Australian colonies, the interconnection between convictism and enslavement, and the repressive policies enacted by the East India Company in response to subaltern resistance to its expropriation of land and other resources in the Indian subcontinent. It will trace convict journeys across the Bay of Bengal, and further afield in the Indian Ocean, and discuss aspects of convicts’ lives in penal locations, notably the labour that they performed in port cities and their relationships with other workers. It argues that Indian convict transportation was one element of a connected imperial repertoire of repression, coerced labour extraction, and the expansion of East India Company governance and trade. The Company used transportation as a means of removing resistant subjects from their homes, and of supplying a malleable labour force to build the commodity chains and infrastructure necessary for the establishment, population, and connection of imperial port city nodes, with each other and their hinterlands. Depending on the availability of labour locally, as well as changing ideas about ideal forms of punishment and rehabilitation emanating from metropolitan Europe and Australia, convicts sometimes worked in parallel with other workers, including slaves, lascars, migrants, and locally convicted prisoners.

Paradoxically, though the Company deployed penal transportation as a means of quashing rebellion and resistance, the close confinement and association of convicts during their often long journeys to ports of departure and ports of arrival, over land, and by river steamers and sailing ships, rendered transportation a vector for their spread. Transportation thus enabled convicts to develop transregional political solidarities, and as such was productive of violent and collective anti-Company uprisings. It is now widely recognized that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, port cities in the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean were places of cosmopolitan interaction, the economic and social meeting places of Asian sojourners and settlers, in which both friction could arise and syncretic cultural and political solidarities could form.Footnote 3 What is perhaps less appreciated is the extent and importance of convict transportation for the cosmopolitanism of these sites. Refocusing on the turn of the nineteenth century and the decades up to the 1850s compels us not just to incorporate forced labour into the history of port cities and their cultural formations, but also to root the development of transregional anti-imperial solidarities to a much earlier period than has been previously recognized. This provides a new perspective not just on the history of port city workers and their solidarities, but on cosmopolitanism as an expression of the power of the colonial state during a crucial period in the globalization of capital. Following Britain's loss of the American colonies, metropolitan interests swung to the east, flinging unfree labour together and producing new forms of labour association, particularly in the often transitory and fluid context of port cities. These connections both cut across social hierarchies grounded in civil status, ethnicity, and race, and linked together the Company's regional hubs.Footnote 4

CONVICTS, ENSLAVEMENT, AND EMPIRE

The East India Company instigated the transportation of Indian convicts in the late eighteenth century, in the context of a two-century-long history of British and Irish penal banishment, military impressment, and the selling of convicts into contracts of labour indenture in the Americas. Sixteenth-century destinations included Bermuda, Barbados, and Virginia, including for Scottish prisoners of war and Irish rebels. Gwenda Morgan and Peter Rushton have described other elements of this human cargo, partially constituted of vagrants and capital respites, as “the uncontainable poor”.Footnote 5 Penal transportation became a more routine part of the criminal justice system after the passing of the 1717 Transportation Act, when the government extended the punishment beyond those offenders pardoned from execution. During the period up to the outbreak of the American War of Independence in 1775, Britain and Ireland shipped at least 50,000 convicts to Atlantic world plantation colonies, including Barbados, but also and in particular around the Chesapeake Bay. Hamish Maxwell-Stewart argues that American planters’ initial preference for a supply of expendable convict labour enabled the capital accumulation necessary for the development of industrial slavery, rendering convictism “the ideological precursor of plantation racism”.Footnote 6 In 1775, the North American colonies refused to accept further transports. Subsequently, many convicts were incarcerated in prison hulks along the river Thames, and these quickly became overcrowded. The British sent a few batches of convicts to West African forts (including slave trading posts), but high death rates meant that this experiment did not last long. It was in the context of the failure of its African convict experiment that the government took the decision to use convicts to establish a new colony at Botany Bay, dispatching the first fleet to the southern Indian Ocean in 1787.Footnote 7

A full twenty years before the abolition of the slave trade across Britain's Crown Colonies in 1807, and a year after the first fleet sailed to the Antipodes, across two oceans from the former American colonies Governor General of Bengal Charles Cornwallis prohibited the export of slaves from the presidency. Subsequent to the Bengal prohibition, both Indian and European elites continued to own slaves, but the East India Company no longer traded in them.Footnote 8 During this period, metropolitan abolitionists were arguing forcefully against the Atlantic slave trade, on the grounds of both humanitarianism and political economy. Many such abolitionists had political and economic interests connected to those of the East India Company.Footnote 9 Bengal's abolition of slave exports enabled them to claim India as a space of enlightened labour relations, and thus to seek advantage in global markets that were increasingly sensitive to the expropriation of slave labour.Footnote 10

It would be another four decades before contemporaries compared convicts to slaves. This came in the aftermath of the abolition of slavery in parts of the British Empire (not including East India Company Asia), in 1834, and in the context of a growing anti-penal transportation lobby, active in Britain and the Australian colonies. In the meantime, both the British state and the East India Company remained committed to transportation as a means of putting into motion an alternative unfree labour supply. Thus, in the dual context of Britain's first convict shipments to Australia in 1787 and Bengal's prohibition of slave trading in 1788, in 1789 the Company sent the first convoys of convicts to its trading factories. From the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries the Company used Asian convict labour as a means to develop the infrastructure necessary to link port cities to each other, and then to build the roads and bridges vital for the connection of land, littoral, and sea. With very few exceptions, Asian convicts worked exclusively for the Company, and except during an early, experimental period they were not hired out to private individuals or used in private trading.

The trading factories were a distinct feature of East India Company Asia. From the start of the seventeenth century, the Company had sent merchants (“factors”) from Britain to the east to strike deals with local rulers, and to establish trading posts (or “factories”) as nodes of economic interest. The Company founded its first factory on the coast of western Java, at Bantam. It established others both in continental India and southward of the Bay of Bengal, in Sumatra, Borneo, the Molucca Islands, and, in common with the Dutch East India Company, Java (see Van Rossum in this Special Issue). The Indian factories ultimately developed into the three “presidencies” of Bengal, Madras, and Bombay, and this enabled the first Governor General of Bengal, Warren Hastings, and his successors, including Charles Cornwallis, to further expand the Company's sphere of influence. The Company defeated local rulers to extend its territories inwards over land and outwards over sea, and seized or acquired numerous rights of governance, including the power to collect revenue and to administer justice.Footnote 11

Though the Company ceded its Indonesian territories to the Dutch following the 1814 Treaty of Paris, which concluded the Napoleonic Wars, its expansive ambitions continued. It had occupied Penang in 1786,Footnote 12 the Andaman Islands in 1793, Malacca in 1796, Singapore in 1819, and the Arakan and Tenasserim provinces of Burma in 1826. The Company abandoned the Andamans in 1796, due to extraordinarily high deaths rates, and exchanged Bencoolen for Malacca, through a second Anglo-Dutch treaty in 1824. In the meantime, and subsequently, the Company shipped Indian convicts under sentences of transportation and hard labour to each of these locations. The Company lost its monopoly over trade in 1833, following pressure by the free trade lobby on the British parliament. However, it retained its administrative and revenue collecting functions until 1857, when, following the Indian rebellion, the British Crown assumed control of its territories. In the intervening period, penal transportation continued unabated, as the Company instituted this new form of mobile, coerced labour to underpin its expansive ambitions.Footnote 13

During an early, experimental period the Company allowed a private merchant to take twenty dacoits (gang robbers) to Penang for a period of three years, and to employ them as he desired, on condition that he pay the cost of their passage, accommodation, rations, and return, and do everything in his power to prevent their escape. This was the first and last time that the Company organized the transportation of convicts in this way, and subsequently it took direct control of their shipment and labour.Footnote 14 Meantime, it justified transportation as a punishment by claiming that Indians lost caste during sea voyages, and so especially feared journeys over the kala pani, or black waters of the ocean. This rendered it ideal as both a penal sanction and as a deterrent.Footnote 15

The Company never sold Asian convicts into contracts of indenture, as had been the case for the British and Irish convicts sent to the Americas. This was the result of a paradox: the Company's desire to position itself as the harbinger of enlightened labour relations, compared to the British Caribbean slave colonies, and its need for a labour force to facilitate the acquisition and development of maritime connections and territorial spheres of influence. Thus, penal transportation from British India followed Australian practice, where convicts were sentenced either for a term of seven or fourteen years, or for life, with hard labour, and the government determined how they should be employed.Footnote 16 If the British had used convicts as a means of colonizing the Australian continent, the appeal of the punishment in India at this time, though partially grounded in perceptions of “Indian” culture, was directly connected to the Company's need for labour in territories that it had already occupied, and in this port cities were hubs. Moreover, the Company's interests as a trading company intersected with those of the British Crown as an imperial power. Indeed, convicts flowed across the borders of Company and Crown lands, from India to Mauritius and from Ceylon to the Straits Settlements, with convict expulsion and exploitation of mutual political and economic benefit (Table 1).

Table 1. East India Company convict transportation, 1789–1866.

* It is not always possible to distinguish these destinations in the records, though note that the Company occupied Amboyna only between 1796–1802 and 1810–1814.

Note: Under-sentence convicts remained in these penal settlements after new importations of convicts ceased. The penal settlement in Mauritius remained open until 1853, Burma until 1862, and the Straits Settlements (as Penang, Malacca, and Singapore were known after 1826) until 1868, in the latter case after the India Office transferred their general administration to the Colonial Office.

Clare Anderson, “Transnational Histories of Penal Transportation: Punishment, Labour and Governance in the British Imperial World, 1788-1939”, Australian Historical Studies, 47:3 (2016), Table 1, p. 382.

Despite the late eighteenth-century Bengal prohibition against slave exports, slavery remained legal in areas under East India Company control until 1843, and in some of the early factories, convicts and enslaved people worked together. In the Moluccas, for instance, following a devastating smallpox epidemic that decimated both the free and the enslaved population, in 1801 the Company imported convicts to assist slaves and Malay labourers (then called “coolies”) in salvaging the harvest on its nutmeg plantations. The Company's resident, R.T. Farquhar, lamented that since the British takeover, five years earlier, there had been no fresh importations of enslaved people, and this was causing unprecedented “universal distress”.Footnote 17 During this period, the Company also transported convicts to Bencoolen, where many Malays had also died, for the harvesting of spices.Footnote 18 In 1818, the British governor of Bencoolen, T.S. Raffles, emancipated government slaves, an act of apparent benevolence that, in the context of the Company's desire for global labour advantage, was only possible because of the prospect of their replacement by convicts. Indeed, in the aftermath of emancipation, convict numbers in the factory increased fourfold.Footnote 19

The close relationship between convictism and enslavement that was evident on the spice plantations of Company Asia during these early decades was also a feature of the Crown Colony of Mauritius. In 1814, shortly after Britain seized the island from France at the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, Governor R.T. Farquhar, who, as Company resident in the Molucca Islands, had overseen the introduction of convicts, requested a supply from Bengal.Footnote 20 The first transports arrived in 1815, and he allocated seventy-five of them to join enslaved men and women on the sugar plantation of Bel Ombre, in which his private secretary Charles Telfair had an economic interest.Footnote 21 In Mauritius as in Bencoolen and Amboyna, the British catapulted convicts into an economic system that had been established through conditions of labour unfreedom. Convicts joined slaves as foundational links in chains of commodity production and export that stretched from imperial hinterlands to imperial ports. In this, alongside other workers, convicts played a key role in the globalization of capital.

COMMODITY CHAINS, INFRASTRUCTURAL LABOUR, AND CONVICT WORKERS

If the transportation of convicts was a consequence of the Company's expropriation of land and resources in continental India, it enabled the appropriation of labour and the extension of commodity chains. As one Company merchant, R.S. Perreau, wrote in 1800, penal transportation to Bencoolen was “connected with the improvement of this settlement, and the opportunity […] of relieving [the] different zillahs (districts) from a number of subjects who are burthensome and expensive”. He surveyed the trading factory's district of Benterin, reporting on its suitability for the cultivation of rice, cotton, mustard, hemp, Indian corn, sugar cane, sweet potatoes, and mulberries. Noting that many of the convicts in Bencoolen were weavers, he proposed their employment in the manufacture of cloth. They could cultivate rice, too, he added, obviating the need for imports and enabling ships “to be occupied by more valuable goods”. Convicts’ manufacture of gunny bags from hemp, meantime, could replace the 30,000 or so imported from Bengal each year, necessary for packing the pepper grown in the factory.Footnote 22

Convicts were the human capital in a triangular trade that reached from the Company's interests in India and around the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea, and across the southern Indian and South Atlantic Oceans to Britain. There were no special transportation vessels during the first half of the nineteenth century. Convicts travelled on “country” ships carrying cargo such as cotton, tea, indigo, and opium. They assisted in the labour of offloading that cargo in the Company's trading factories, and of loading up goods like nutmeg and pepper for export.Footnote 23 Dockside work occupied just a small number of convicts, however. The Company employed the majority of them in the infrastructural labour projects necessary for the extension of trade, or in other kinds of commodity production. The concept of “carceral circuits” – of people and objects – captures neatly the mobility and relationality between convicts and capital in the generation of value.Footnote 24

The labour of convicts was important from the earliest years of transportation. From the 1790s, the Company was involved in numerous trials in sugar production in continental India, in the hope of both supplying the local market, and competing with Britain's West Indian export trade to lower prices for British consumers. Though ultimately unsuccessful, abolitionist sentiment greatly encouraged the Company, for it pointed to the east as an alternative source of non-slave-produced sugar.Footnote 25 During the first attempt to colonize the Andaman Islands, for example, convicts cleared land, planted fruit trees and vegetables from Bengal, and engaged in experiments in the cultivation of sugar cane, as well as rice, indigo, and other grains.Footnote 26 The employment of convicts in other forms of cultivation was common elsewhere too. As noted above, the Company used convicts on the spice plantations of Bencoolen and Penang. From the 1840s, Burma and the Straits Settlements did not only receive Indian convicts, they also transported their felons in the other direction, to the Madras Presidency. They were employed on the Company's coffee and cinchona plantations.Footnote 27 Convicts in Mauritius were used in experimental silk manufacture, during which time the governor specifically requested the transportation of Bengalis with knowledge of sericulture.Footnote 28 On a few occasions, the Company also conscripted convicts into its army, and used them in expansionary warfare, for instance in the 1800 march to Laboon, and during the Naning War in Malacca (1831–1832).Footnote 29

The expansion of plantation production necessitated the development of road networks for the conveyance of produce to the coast for export, as well as to build infrastructure in the Company's ports. However, in early trading factories like Penang, the free population engaged in subsistence agriculture and did not have the means to pay tax to fund public works. In 1800, Lieutenant Governor George Leith wrote that in these circumstances only convicts could save the Company from “considerable expense”, especially because roads were routinely damaged by heavy rains and thus under constant repair. During that year, it employed convicts in Penang not just on road building, but also on the construction of a mile-long embankment between the sea and Fort Cornwallis, necessary to prevent encroachment from the water.Footnote 30

In Mauritius, the expansion of road networks was spurred on in 1825, when the British Parliament removed preferential tariffs on Caribbean sugar, thus opening up competition in global trade. We have already seen that Governor Farquhar sent Indian convicts to work on the Bel Ombre sugar plantation; between 1814 and 1832 the proportion of land under sugar cane cultivation increased from fifteen to eighty-seven per cent. Convicts built fifty miles of brand-new road during 1823–1826 alone, and another twenty-six miles in 1835. These included routes from inland Moka to Port Louis, and a coastal route between the south-eastern ports of Grand Port and Mahebourg. Visiting the island during his global voyage on The Beagle in 1836, Charles Darwin surmised that the huge increase in sugar production was the direct result of the construction of “excellent roads” by convicts. Frequently, French plantation owners petitioned the British administration for the allocation of convicts to road and bridge building and repair in the districts.Footnote 31

There was a high demand for cheap sugar to fuel the British workers employed in the mills and factories of the industrial revolution, and the abolition of slavery in the sugar colonies of the Caribbean and in Mauritius in 1834 buoyed the Company's efforts to compete globally.Footnote 32 In the mid-1840s, it engaged in the clearance of forest land for sugar production in the north of Province Wellesley in Malacca, on the mainland over the straits from Penang. This required an enhanced network of communications, and the governor of the Straits Settlements diverted an increased number of convicts to both areas for road building projects.Footnote 33 The convict-built roads connected the hinterlands to convict-built ports. Indeed, all over the Bay of Bengal convicts were engaged in the construction of bunds, docks, harbours, and lighthouses. Convict Bawajee Rajaram and his convict draughtsmen produced many of the architectural plans in the building of Singapore, for example, where convicts constructed St Andrew's Cathedral, Government House, and the Horsburgh lighthouse.Footnote 34

The association between convict transportation and infrastructural development in British Asia and the Indian Ocean was part of a larger imperial pattern. Transportation convicts across the empire were routinely employed in urban development and the building of communication networks, linking port cities and their littorals to each other and to inland plantations. As Jennings shows in this volume, this was also the case in nineteenth-century Cuba. In Britain's Australian penal colonies, famous convict architect Francis Greenway designed some of the most enduring structures of the empire, including Hyde Park convict barracks in Sydney and the lighthouse at South Point. Indeed, in the 1820s, the aesthetic appeal of his elaborate designs formed part of the damning critique of transportation to New South Wales as a too soft and non-deterrent punishment.Footnote 35 From the 1820s, English and Irish convicts laboured on the construction of the great naval dockyards of the imperial Atlantic and Mediterranean outposts of Bermuda and Gibraltar.Footnote 36 Convicts in the isolated penal settlement of Mazaruni in British Guiana, set up along the Australian colonial model in 1843 but for locally convicted prisoners, worked in the extraction of granite from vast outcrops of rock. Prisoners in the penal settlement, some formerly enslaved, dispatched the slabs downriver to the capital of Georgetown, accompanied by batches of convicts, who used them to build and repair roads, pavements, and sea wall defences.Footnote 37

The question arises: why did the East India Company rely so heavily on convicts as labour? In part, the answer lies in Perreau's summation of the function of transportation as a means of putting otherwise dependent and costly prisoners to work in colonial development – within the larger context of the metropolitan history of penal transportation and the striving for competitive advantage described above. But the answer is also located in the problem of the availability of alternative sources of labour following Bengal's abolition of slave exports in 1788, which impacted on all of Company Asia, and in regard to Mauritius specifically the Crown's abolition of the slave trade in 1807. Places like Bencoolen were thinly populated, and with the enslaved population in decline free labour was expensive. In the early nineteenth century, Company officials routinely claimed that convicts cost half as much as local Malays and were far cheaper than other labour sources.Footnote 38

Indeed, in Burma in the 1840s, the Company found it impossible to get locals or migrants to accept the wages on offer. The commissioner of Arakan wrote in 1845 that the former owned land, and so lacked skills in public works, and would only hire themselves out at very high rates. The latter, largely Bengali labourers from Chittagong, moved south only during the harvest and returned to India as soon as the monsoon arrived. They were only available in very limited numbers. Though he had been able to employ free labourers in parallel with convict gangs, the commissioner made observations in the following terms:

I never met a Chittagong cooly who could […] line out a road properly, preserve an even surface, rand down and consolidate the earth, keep the proper slope, or excavate with neatness and regularity; in fact [,] the difference between the labour of a convict and cooly was all the difference between skilled and unskilled labour.Footnote 39

The appeal of convict labour was also connected to the coercive means at the Company's disposal in its management. A combination of confinement, surveillance, and restrictions on mobility deterred convicts from running away. The Company paid local residents to return any who attempted to escape. Otherwise, it compelled convicts to work, and overseers could punish those who refused or resisted work: with confinement in the stocks, enhanced labour tasks, reduced rations, flogging, or work in chain gangs. This was not the case for free laborers, who if unhappy with their conditions could simply desert their work. Threatened by the Company with the withdrawal of transportation convicts, the second principal assistant commissioner of Arakan wrote in 1853: “We should not have the hold over coolies that we have over the convicts”.Footnote 40 In addition, convicts were highly mobile, and could be sent out to labour wherever required, and moved around the trading factories according to need. Indeed, the Company codified such mobility in one of its regulations on transportation, which passed into law in 1813.Footnote 41

The supply of convicts was always limited to the outcome of judicial sentencing, however, and where local labour was either unavailable or in short supply the Company made efforts to induce free migration. Until the 1830s, these attempts met with only limited success. For instance, in the 1790s, the Company shipped free Bengali artificers (skilled craftsmen) and tradesmen to the Andamans, and artificers and cultivators to Penang.Footnote 42 At this time it could not persuade skilled laborers to go to a third site: Bencoolen.Footnote 43 This was part of a larger problem during the early settlement of trading posts, when potential labour migrants were unwilling to go to unknown locations.Footnote 44 Still, as Company factories developed into port cities during the first half of the nineteenth century they accommodated numerous kinds of mobile labour. This included Chinese workers in Bencoolen, the Moluccas, and Penang, who, during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the Company persuaded to migrate on the promise of land grants.Footnote 45 By the 1840s, Chinese labourers had also settled in Malacca.Footnote 46 More generally, the need to bring complementary skills together with raw labour power meant that transportation convicts were sometimes one element of a much larger workforce. This was the case in Mauritius, for instance, when Indian convicts laboured on the construction of the Port Louis citadel alongside government slaves, liberated Africans,Footnote 47 locally raised corvée (compulsory) workers, and locally convicted prisoners.Footnote 48 A strikingly similar mixed labour force, including the use of liberated Africans, was engaged in building the Rio de Janeiro penitentiary in the mid-nineteenth century (see Jean's article in this volume). In Burma, convicts and Chinese worked in mines following the discovery of tin in 1838, up the Tenasserim River from Mergui. Ultimately, the Chinese were willing to take low “coolie” wages, and so displaced the convicts.Footnote 49

In the 1840s, the British employed Bombay convicts in Aden on the works necessary to carve a military post out of a vast outcrop of barren rock. Balancing the cost of shipment, accommodation, and the jail establishment against the value of convict labour, in 1842 the Bombay political agent in the port claimed that convicts did more work than free laborers, because he put them to task work, and that excepting the cost of their initial passage they cost him less.Footnote 50 Administrators elsewhere spent a great deal of time estimating convict labour value, and were frequently in dispute with each other about how best to construct their accounts – including how to divide over the years the cost of a convict's passage, and how to factor in the cost of employing overseers and guards. Clearly, convict labour was at a premium, where there was no alternative supply of workers (and thus labour was unattainable or wages were high). But administrators disputed the amount of work that they completed each day. Perhaps most importantly, however, and as administrators recognized, convicts performed work that would not otherwise have been completed, for the Company did not allocate sufficient resources for the hire of free workers. W.J. Butterworth, governor of the Straits Settlements, noted in 1847 that for this reason it was impossible to calculate the true value of convict labour. The port of Singapore, he wrote, “owes all and everything” to convicts, and Penang and Malacca were similarly indebted to them for the building of roads and canals, and the draining of swamps. Their value, he concluded, was always greater than statistical comparisons with free labourers implied.Footnote 51

REPRESSION AND REBELLION

Most of the convicts involved in the 1851 outbreak in Moulmein, a description of which opened this article, were from the Punjab, which the Company had annexed in 1849 following its victory in the first and second Anglo-Sikh Wars of 1845–1846 and 1848–1849 (Figure 1).Footnote 52 In the aftermath of these wars, the British convicted, jailed, and transported dozens of former soldiers to mainland prisons or penal settlements in South East Asia (Figure 2), many under charges of “treason”. These military men were well trained, drilled, and experienced in handling weapons. In later years, particularly after remaining loyal to the East India Company during the Indian rebellion of 1857, the British came to favour men of this region for employment in both the Bengal army and the Indian police service. They constituted one of India's “martial castes”, for their alleged physical superiority and military prowess.Footnote 53 During the intervening decade, however, they were certainly not preferred prisoners or transports. Defeated, demoralized, and dispossessed, Punjabi soldier convicts carried anti-imperial sentiment with them into transportation, and agitated continuously against their penal confinement, sometimes in concert with ordinary convicts.

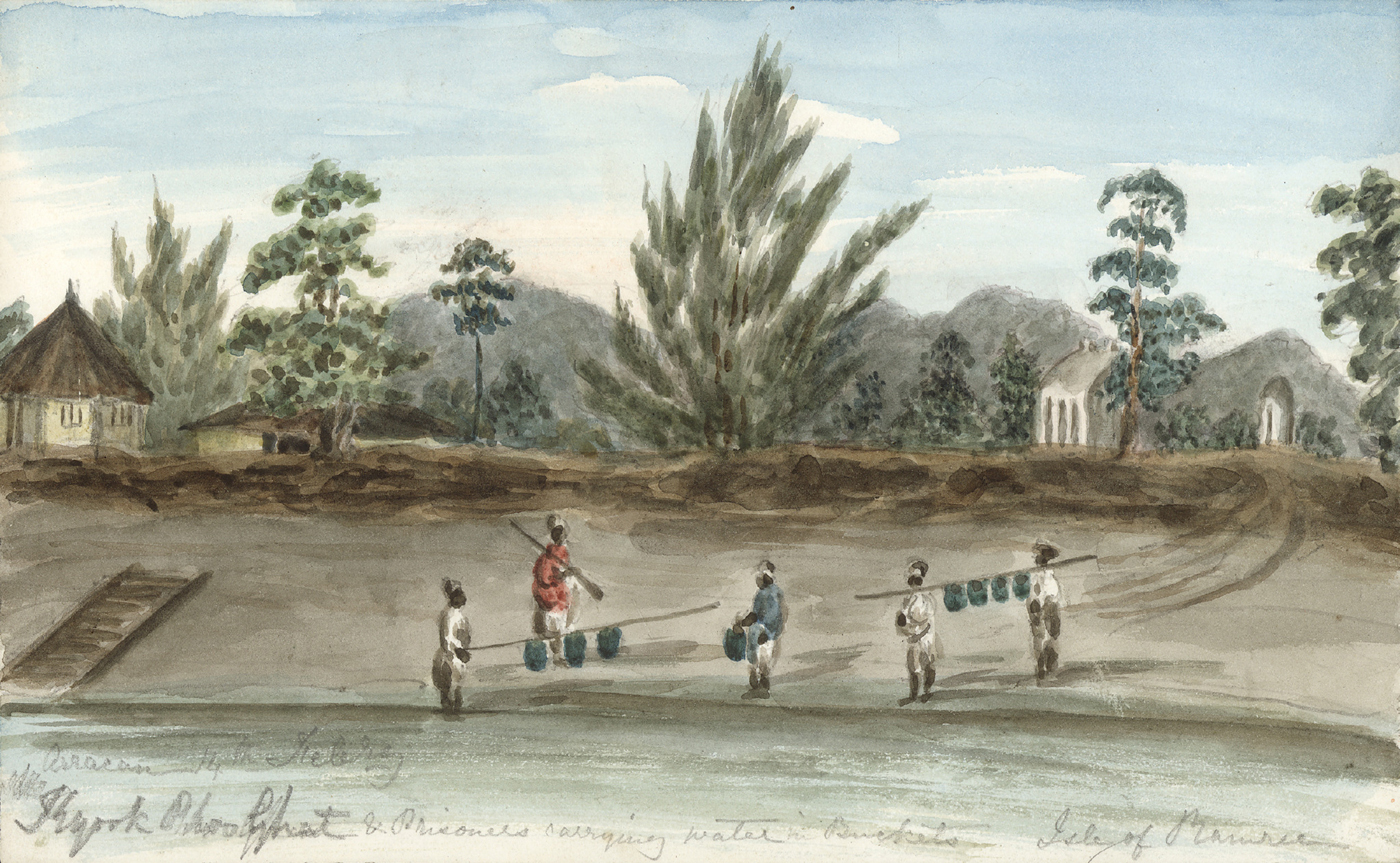

Figure 1. Arracan [Arakan] 14th February [1849] Kyook Phoo [Kyaukpyu] Ghat & Prisoners Carrying Water in Buckets, Isle of Ramree. Watercolour by Clementina Benthall.

Benthall Papers, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge.

Figure 2. Indian Ocean Penal Settlements.

In Burma, for instance, convicts organized mass escapes after a general tightening up of discipline, including the introduction of common messing. The new rules prescribed that convicts should cook and eat their rations together, rather than in self-selecting groups, according to their own desires or cultural and religious imperatives. In November 1846, convicts attempted to break out, and when they failed instead burnt down their wards and guard rooms.Footnote 54 A month later, a road gang of 120 mounted but did not succeed in another mass escape attempt. Clearly pre-organized, the jemadar (head overseer) heard one convict say to another shortly before giving the signal to attack the tindals (overseers), “Are you ready?” The commissioner of Arakan claimed that the outbreak was at least partly the consequence of the convicts’ knowledge that he had no power to sanction them, for they were already subject to the severe punishment of hard labour in chains for life.Footnote 55 In 1849, there was a mutiny at the Moulmein coal depot in Mopoon (which preceded the event that opened this chapter by two years). One hundred convicts employed in preparing coal for delivery to the Company steamer rose against their guards. They, too, failed in their bid to escape, with the Company guard killing three and severely wounding eight men in an effort to prevent their flight. British commissioner Bogle reported: “the Secks had […] bound themselves by an Oath never to return to the prison and to eat beef sooner than abandon their purpose […] Bold men will ever be found keen to emancipate themselves from thraldom, and when determined upon it, they are not to be restrained […]”.Footnote 56

The following year, 1850, a military general named Narain Singh led a violent mutiny among thirty-nine convicts on board a river steamer on the way to Alipur jail, in Calcutta, which was the holding depot for transportation to Burma. After quelling the outbreak, and securing the convicts, they continued to plot their escape, including in prison stops along the way.Footnote 57 There were significant logistical challenges both in moving convicts securely into transportation, and in keeping them to labour in relatively open environments, which often bordered rivers or the sea. This was of course most notably the case in ports. Though convicts failed in their bid for freedom on that occasion, there and in the other cases noted above, their penal mobility – across land, along water, and in outdoor working gangs – put them into close physical contact, which was necessary for the planning of collective action. Paradoxically, whilst the Company effected transportation as a punishment, it also put into motion the spread of rebellious sentiments to the port cities of South East Asia.

The penal transportation of the soldiers of a defeated army following the Anglo-Sikh Wars was entirely consistent with Company justice, which can be dated in this regard to the turn of the nineteenth century. Following the loss of their kingdom during the wars of 1799–1801, Polygar chiefs, for instance, were shipped by the British from south India to both Fort William (Calcutta) and Penang.Footnote 58 Repressive penal transportations also followed the final crushing of the Chuar rebellion in 1816, the second and third Maratha Wars (1803–1805, 1816–1819), the Kol revolt of 1831, the 1835 Ghumsur war against the Konds in Orissa,Footnote 59 the 1844 anti-Company revolt in the princely state of Kolhapur,Footnote 60 and the Santal hul (rebellion) of 1855.Footnote 61 During this entire period, the East India Company also used transportation to expel peasant rebels, particularly low caste and tribal subjects resistant to the Company's occupation of land, extraction of natural resources (notably the timber used for railway sleepers), and taxation regime.Footnote 62

The political convicts of Company Asia joined forces with ordinary, “criminal” convicts to resist their situation at every turn. In 1816, for instance, a dozen convicts rose up and escaped from the Bel Ombre plantation in Mauritius. Some of these men had been sepoys (soldiers), others were low-caste Kols or Chuars who had been convicted of offences relating to peasant rebellion in the Bengal Presidency. They had been confined together to await their transportation in Calcutta's Alipur jail, where a few of the men had been involved in serious riots and were transported in groups on three separate transportation ships. These men were religious rebels of sorts, protesting against the contravention of caste norms regarding the sharing of cooking and eating pots. They stole weapons and escaped into the mountains, allegedly joining a band of maroon (runaway) slaves. In the ensuing trial at the Court of Assizes, they called each other camarade (in French or Mauritian Kreol, comrade) or bhai (Hindustani for brother).Footnote 63 Kolhapur rebels transported to Aden in the mid-1840s likewise led repeated escape attempts, including one collective effort in which Company guards shot dead three convicts, whilst at least ten others drowned in their bid to escape.Footnote 64

Though it succeeded in the expulsion of undesirable imperial subjects, transportation failed as a means of containing anti-imperial sentiment and action. Rather, it facilitated its spread, with subaltern action often turning on the same socio-political grievances that had underpinned convicts’ initial transportation. As noted above, the close confinement of convicts’ river journeys enabled them to plot collective action. The same was true of sea voyages, and there were over a dozen convict mutinies in the period to 1857. Many were both effected and repressed with spectacular levels of violence. The largest of all was the seizure of the Clarissa by more than one hundred convicts in 1854. This failed when the convicts ran aground off the coast of Burma and attempted to sign a treaty with a local ruler, in the false belief that he was holding out against the East India Company. In fact, he had already signed a treaty with the British.Footnote 65 In regard to the importance of often long journeys into transportation as spaces of rebellion, it is significant that the Company often referred to transportation convicts as transmarine, that is to say, from the other side of the sea. This connected together convicts’ place of origin to their journeys and destinations in a way that suggested, implicitly at least, a close relationship between the three.

The 1857 revolt in India proved a turning point in the history of Indian convict transportation, as the British recognized and feared the consequence of the spread of transregional solidarities of resistance in their Asian settlements. One of the Punjabi convicts sent to Singapore following the Second Anglo-Sikh War, for example, Nihal Singh, had led anti-British forces and was widely regarded as a “saint-soldier”, known by the honorific title Bhai Maharaj (“brother ruler”) Singh. The British deputy commissioner wrote at the time: “He is to the Natives what Jesus Christ is to the most zealous of Christians. His miracles were seen by tens of thousands, and are more implicitly relied on, than those worked by the ancient prophets […] This man who was a God, is in our hands”. Afraid of his influence in the cosmopolitan working environment of the port, the British did not put Nihal Singh to ordinary labour, and attempted to keep him away from both convicts and free workers. He had been transported to Singapore with Khurruck Singh, who the British described as his “disciple”. By the time of the outbreak of rebellion in 1857 Nihal Singh had died, but the British expressed grave anxieties about Khurruck Singh's influence on the convicts and Indians then in Singapore. The British had formerly allowed him to live at large, under police surveillance, and he had gone to live with a free Parsee spice merchant. After the outbreak of revolt in the mainland, however, the governor of the Straits Settlements ordered his confinement in the civil jail, and no longer allowed him freedom of movement. Meantime, fearing revolutionary contamination, they evacuated all the “Sikh” convicts then in Singapore, some to the penal settlement of Penang.Footnote 66

In the port city of Moulmein, too, the British feared the spread of rebellion. In July 1857, the superintendent of the jail reported that the convicts possessed “a most unsteady feeling”. A shipload of fifty convicts had arrived on the Fire Queen, bringing, he claimed, “exaggerated stories” with them. The Company had put them in heavy chains, and in distinction to routine transportation practice they were guarded by Europeans, not Indians. The officiating commissioner refused to land them, however, directing them back to Calcutta. He wrote that, like the newly arrived convicts, the jail peons and town police were nearly all “up countrymen” (i.e. from northern India). Moreover, there were 250 ticket-of-leave convicts in the port. “From conversations which have been overheard”, he reported, “it is not impossible that they and a portion of the Mahomedan population of the Town might form a collusion for a general outbreak of the Jail”.Footnote 67 This fear was certainly not groundless, for one of the key features of the 1857 revolt was the breaking open of prisons. The consequence of this alliance between rebels and prisoners was the serious damage or destruction of over forty jails, and the escape of over 20,000 inmates.Footnote 68

CONCLUSION

During the period 1789 to 1866, transportation was linked to the repressive policies of the East India Company. Underpinned by representations of its peculiar appropriateness as a punishment in India, the Company used it as a means of removing rebels and undesirable criminal offenders from their home localities. Following their arrival in the Company's trading factories, Indian convicts played a vital role in building infrastructures of connection that linked port cities of the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean to each other and to their hinterlands. Grounded in wider imperial practice, extending across Britain's empire in the Americas and Australia, convict transportation in this regard was connected to enslavement in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds. However, Britain's Asian system was distinct from other imperial convict flows because the Company's trading factories were hubs in and through which the convict workforce was employed and distributed. The Company used convicts as a means of supplying the workforce necessary to create new circuits of connection to expand commodity production and export. Convicts were one element of the cosmopolitan port city labour force during this vital period in the development of imperial trade. One of the unintended consequences of penal transportation in British Asia was that the close confinement and association of convicts during transportation rendered the punishment a vector for the development of transregional political solidarities, centred in and around the Company's port cities. These created new kinds of unanticipated subaltern connections, in which the violence of penal transportation could be met with the violence of resistance against it.