To the Editor—In 2013, the outbreak registry of the German consulting center for infection control and prevention (Deutsches Beratungszentrum für Hygiene, BZH GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) was instituted as a quality assurance project to analyze outbreak situations to gain epidemiological data and to generate practical advice for the affected institutions. After 5 years, the registry now contains data for 96 outbreaks plus final analyses. Here, we focused on outbreaks affecting healthcare workers (HCWs) as part of the infected or colonized outbreak cohort.

Material and Methods

In contrast to the German legal definition (German infection prevention law, Infektionsschutzgesetz), which defines 2 or more cases of infection with a presumed epidemiological link as an outbreak, our registry only includes “major” outbreaks, which are defined as 5 or more cases of infection or colonization with an epidemiological link or, in cases of special organisms like multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs), highly contagious diseases with 2 or more cases or sentinel cases of special interest.Reference Schulz-Stübner, Reska, Hauer and Schaumann 1 The definition was chosen to limit the analytical effort on common outbreaks (eg, with norovirus) to major events but to include colonization outbreaks without infections if they required comprehensive infection control interventions.

Data from the outbreak analysis were entered without personal identifiers in an anonymized database according to European Union’s (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This was not human research, and data analysis does not require review by our institutional review board. Overall, 94 outbreaks were analyzed regarding information related to involvement of HCWs.

Results

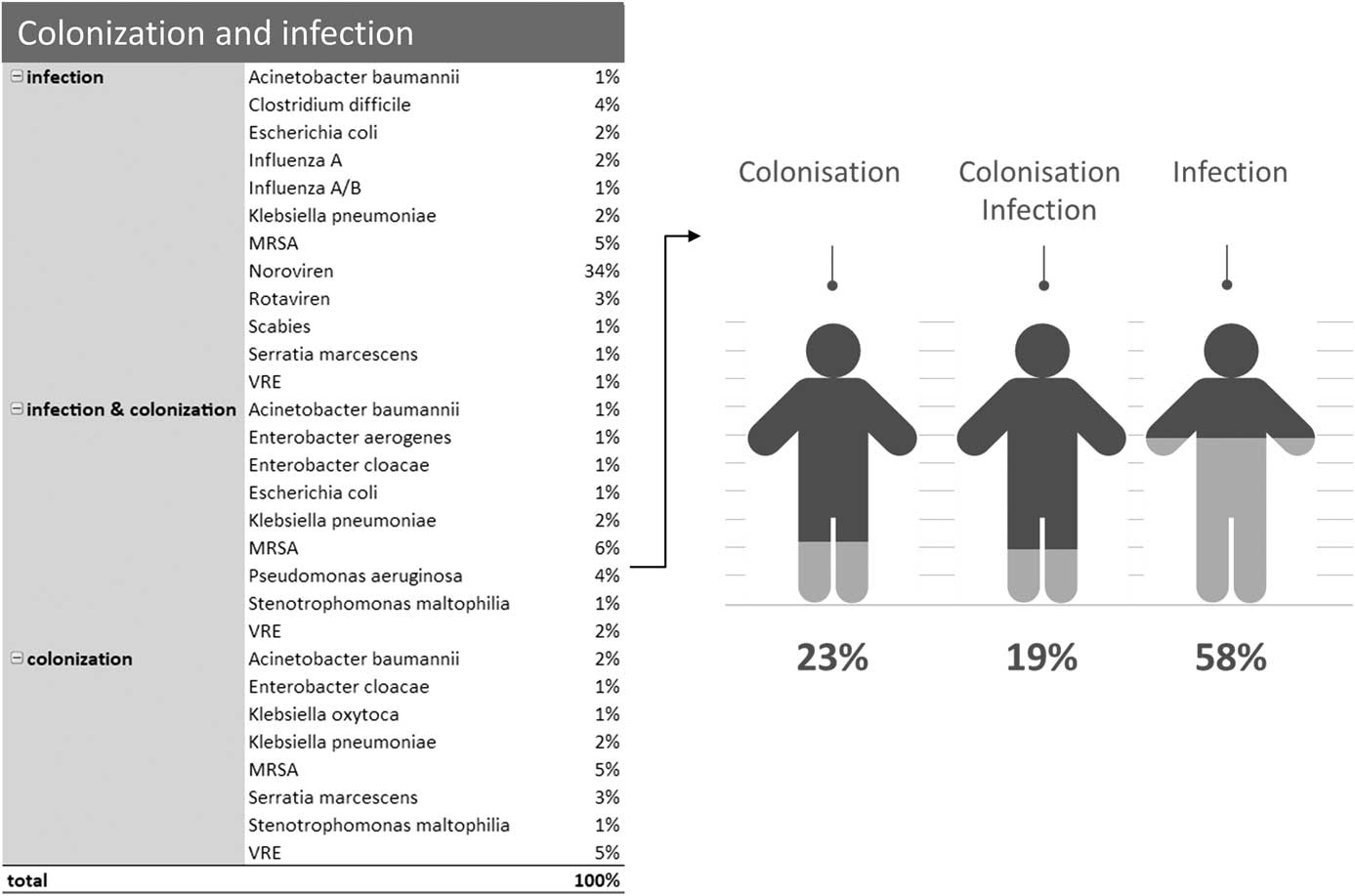

The 94 screened outbreaks involved 464 people with infections and 168 with colonization only. The duration of the outbreak management ranged from 1 day to 185 days; the number of affected people ranged from 1 to 66 per outbreak. Figure 1 shows the distribution of organisms involved and their relation to outbreaks of infections (59%), combined outbreaks with infections and colonizations (20%), and colonization only (21%).

Fig. 1 Organisms involved in 94 outbreaks related to infections, infections and colonization and colonization only.

Overall, 192 HCWs became sick as part of an outbreak: 162 had norovirus infections, 22 had influenza infections, 8 had scabies infections. Furthermore, 2 HCWs were found to be colonized with MRSA in the screenings performed during an outbreak. No clear epidemiological link was identified between MRSA colonization status and the outbreak in 1 case, whereas an HCW was identified as superspreader during an upper respiratory tract infection in the other. In 5 outbreaks with gram-negative MDROs and 1 VRE outbreak, rectal screening of staff was performed without any meaningful results.

The following specific items were identified from the outbreak reports as areas of concern or potential for improvement in outbreaks affecting HCWs:

∙ Overcrowding and staff shortage (influenza)

∙ High staff turnover rate and lack of specifically assigned personnel caring for infected patients (influenza, norovirus)

∙ Mishandling of personal protective equipment, especially during doffing of gowns and gloves (influenza, norovirus)

∙ Lack of influenza vaccination (influenza)

∙ Return to work while still symptomatic, infecting colleagues and patients and resulting in prolonged outbreak situations (influenza, norovirus)

∙ Continuing to work while symptomatic but undiagnosed (scabies)

∙ Lack of awareness of symptoms (scabies)

∙ Lack of compliance with preemptive treatment (scabies)

∙ Diagnostic uncertainty of staff screening results (MRSA)

Discussion

Highly contagious viral diseases like norovirus and influenza were the main cause of HCW illness during outbreak situations in our registry. Although the rate of HCW influenza vaccination is slowly increasing in Germany,Reference Neufeind, Wenchel, Bödeker and Wichmann 2 much improvement is needed, which cannot be compensated by distribution of antiviral medications during outbreak situations, even though the early use of those medications might help to limit the outbreak.Reference Doll, Winters, Boikos, Kraicer-Melamed, Gore and Quach 3

Mishandling of personal protective equipment remains a problem that can be exacerbated by stress at work, overcrowding, and understaffing. Furthermore, understaffing and obligation toward third parties contribute to presenteeism, which can create a vicious circle of continuous transmission, prolonging the outbreak.

Based on our analysis of the outbreak reports, the fight against presenteeismReference Mitchell and Vayalumkal 4 , Reference Tan, Robinson, Jayathissa and Weatherall 5 might be of utmost importance, especially during influenza and norovirus outbreaks.

Broad information about signs of symptoms of scabies and screening for symptoms by occupational health and preemptive treatment of HCWs with unprotected contact with affected patientsReference Leistner, Buchwald, Beyer and Philipp 6 , Reference Buehlmann, Beltraminelli and Strub 7 is needed. Lack of preemptive treatment compliance or application failure might be improved by using ivermectin rather than topical treatment,Reference Garcia, Iglesias, Terashima, Canales and Gotuzzo 8 as demonstrated in scabies outbreaks without staff involvement in our registry.

Staff screening seems only be indicated in MRSA outbreaks with a possible epidemiological link to staff. However, the results need to be interpreted with caution, and molecular analysis or whole-genome sequencing should be readily available to prove or disprove the connection to the outbreak. Otherwise, there is the chance of following a wrong track and missing the real causes of the outbreak. Incidental findings of colonizationReference Dulon, Peters, Schablon and Nienhaus 9 are possible, as demonstrated in 1 of our cases. Avoiding stigmatization of affected staff is an additional challenge that needs to be addressed in advance by a clear institutional policy regarding screening, communication of screening results, and measures to be taken in case of a positive screening result. 10

Acknowledgments

This report is part of an ongoing quality assurance project regarding outbreak management at the German consulting center for infection control.

Financial support

This work was funded with institutional funds only.

Conflict of interest

S.S.S. is shareholder of Deutsches Beratungszentrum für Hygiene (BZH GmbH) and receives royalties from Springer, Thieme, Deutsche Krankenhausverlagsgesellschaft, and Consilum infectiorum.