Significant outcomes

-

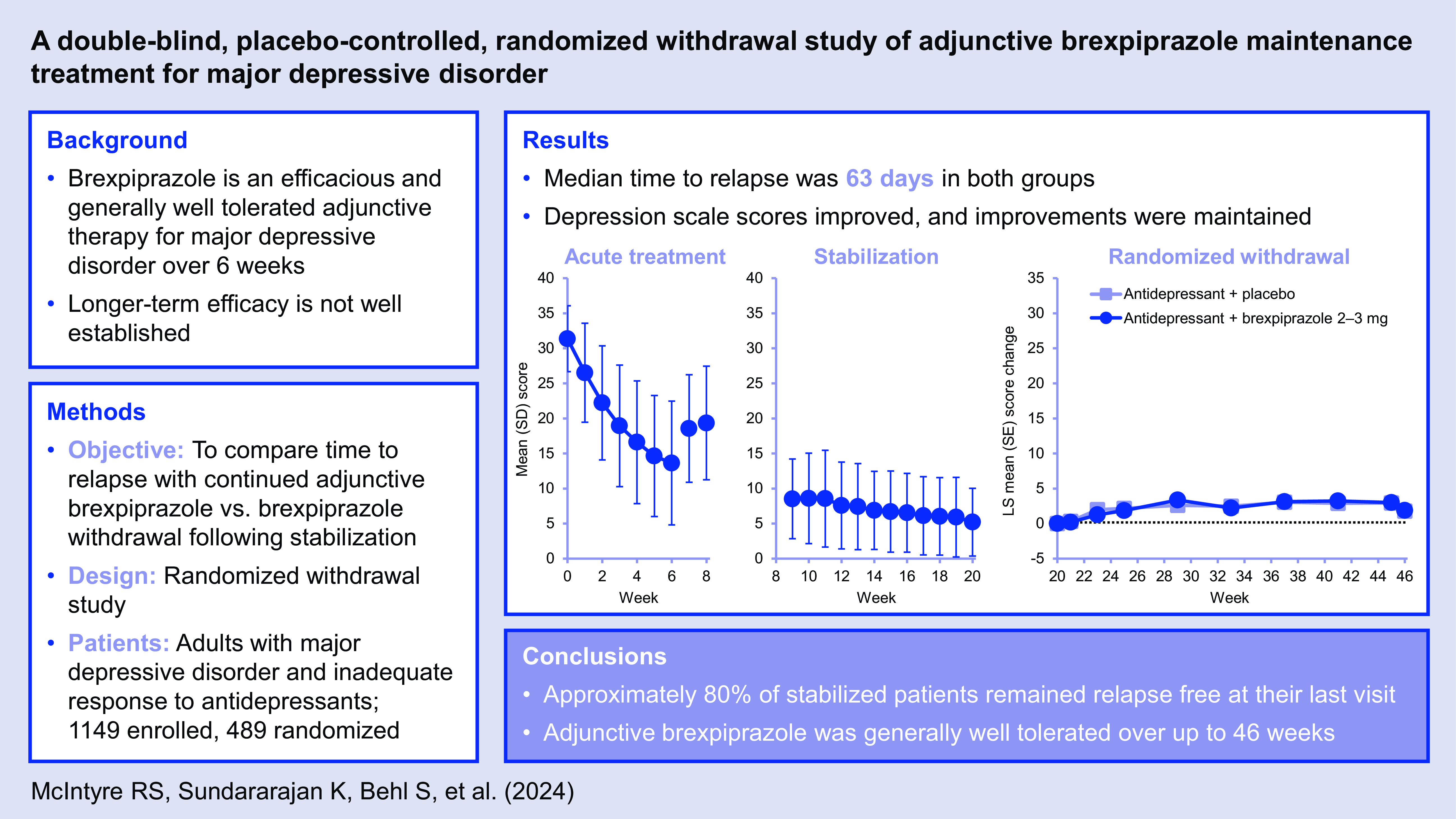

After 18–20 weeks of treatment, discontinuation of adjunctive brexpiprazole in stabilised patients with major depressive disorder was associated with a low risk of relapse and minimal adverse withdrawal effects.

-

Over 26 weeks following stabilisation, time to relapse was similar with continued adjunctive brexpiprazole and brexpiprazole withdrawal; early improvement of depressive symptoms and functioning was maintained in the majority of stabilised patients.

-

Adjunctive brexpiprazole was generally well tolerated over up to 46 weeks.

Limitations

-

Participants received 18–20 weeks of adjunctive brexpiprazole therapy before randomisation; risk of relapse may have been higher if a shorter duration of adjunctive therapy was provided prior to randomisation.

-

There was no active comparator arm (such as another adjunctive antipsychotic) to validate the design and conduct of the trial.

-

Relapse rates were low in the group randomised to brexpiprazole withdrawal, which may suggest that the study lacked sensitivity.

Introduction

Remission, defined as no or minimal depressive symptoms plus improved functioning, is the key goal of acute treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD) (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Pfennig, Severus, Whybrow, Angst and Möller2013). However, relapse rates following remission are high (Sim et al., Reference Sim, Lau, Sim, Sum and Baldessarini2016), and long-term studies show that most patients in recovery will eventually experience a recurrence of depressive symptoms (Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Leon, Keller, Solomon, Endicott, Coryell, Warshaw and Maser1999; Solomon et al., Reference Solomon, Keller, Leon, Mueller, Lavori, Shea, Coryell, Warshaw, Turvey, Maser and Endicott2000). The risk of relapsing up to a year after remission is halved for patients who continue antidepressant treatment (ADT) compared to those who discontinue ADT (Sim et al., Reference Sim, Lau, Sim, Sum and Baldessarini2016). Treatment guidelines therefore recommend continuation of successful MDD treatment for at least 6 months after remission, with longer courses of treatment often recommended for patients with a history of recurrence (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Pfennig, Severus, Whybrow, Angst and Möller2013; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Severus, Köhler, Whybrow, Angst and Möller2015).

Approximately 50% of patients with MDD have an inadequate response to first-line ADT (Rush et al., Reference Rush, Trivedi, Wisniewski, Nierenberg, Stewart, Warden, Niederehe, Thase, Lavori, Lebowitz, McGrath and Rosenbaum2006). Adjunctive therapies are one option for patients who do not obtain adequate benefit from antidepressant monotherapy, and, among several proven adjunctive strategies, the evidence is most extensive for atypical antipsychotics (Connolly & Thase, Reference Connolly and Thase2011; Kishimoto et al., Reference Kishimoto, Hagi, Kurokawa, Kane and Correll2023). However, the longer-term safety and efficacy of adjunctive atypical antipsychotics in patients with MDD is not well established, and the few completed longer-term randomised controlled studies have yielded conflicting efficacy results (Rapaport et al., Reference Rapaport, Gharabawi, Canuso, Mahmoud, Keller, Bossie, Turkoz, Lasser, Loescher, Bouhours, Dunbar and Nemeroff2006; Brunner et al., Reference Brunner, Tohen, Osuntokun, Landry and Thase2014; Mohamed et al., Reference Mohamed, Johnson, Chen, Hicks, Davis, Yoon, Gleason, Vertrees, Weingart, Tal, Scrymgeour, Lawrence, Planeta, Thase, Huang, Zisook, Rao, Pilkinton, Wilcox, Iranmanesh, Sapra, Jurjus, Michalets, Aslam, Beresford, Anderson, Fernando, Ramaswamy, Kasckow, Westermeyer, Yoon, D’Souza, Larson, Anderson, Klatt, Fareed, Thompson, Carrera, Williams, Juergens, Albers, Nasdahl, Villarreal, Winston, Nogues, Connolly, Tapp, Jones, Khatkhate, Marri, Suppes, LaMotte, Hurley, Mayeda, Niculescu, Fischer, Loreck, Rosenlicht, Lieske, Finkel and Little2017; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hefting, Lindsten, Josiassen and Hobart2019).

Brexpiprazole is one of four atypical antipsychotics approved in the US for use as an adjunctive therapy to ADT for the treatment of MDD in adults (Riesenberg et al., Reference Riesenberg, Yeung, Rekeda, Sachs, Kerolous and Fava2023). The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of adjunctive brexpiprazole for the short-term treatment of MDD have been demonstrated in four 6-week Phase 3 randomised controlled trials (Thase et al., Reference Thase, Youakim, Skuban, Hobart, Augustine, Zhang, McQuade, Carson, Nyilas, Sanchez and Eriksson2015a; Thase et al., Reference Thase, Youakim, Skuban, Hobart, Zhang, McQuade, Nyilas, Carson, Sanchez and Eriksson2015b; Hobart et al., Reference Hobart, Skuban, Zhang, Augustine, Brewer, Hefting, Sanchez and McQuade2018a; Hobart et al., Reference Hobart, Skuban, Zhang, Josiassen, Hefting, Augustine, Brewer, Sanchez and McQuade2018b). A longer-term randomised controlled trial found no meaningful difference between adjunctive brexpiprazole and adjunctive placebo on rate of remission over 24 weeks; these results may have been impacted by study design elements, such as a previously untested primary outcome, and the lack of a group switched from brexpiprazole to placebo after an acute response to adjunctive therapy, among other factors (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hefting, Lindsten, Josiassen and Hobart2019).

The aim of the present withdrawal study was to compare time to relapse in patients stabilised on ADT + brexpiprazole who were then randomised to either continued adjunctive brexpiprazole or brexpiprazole withdrawal (a switch to adjunctive placebo). The safety and tolerability of adjunctive brexpiprazole for the maintenance treatment of MDD were also assessed.

Methods

Participants and study design

This was a Phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm, 26-week, randomised withdrawal study in patients with MDD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03538691). Patients were enrolled by investigators at 67 clinical trial sites in the US (70.5% of enrolled patients), Poland (21.8%), and Germany (7.7%).

The study enrolled male and female outpatients aged 18–65 years with a diagnosis of recurrent MDD as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition (DSM-5); a current major depressive episode of ≥8 weeks in duration; and a 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D17) total score of ≥18 at screening and baseline visits (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1960; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1967). At screening, patients were required to have a history of inadequate response to 1–2 ADTs during the current episode, plus a current inadequate response to an adequate duration of protocol-specified selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) treatment, where inadequate response was defined as <50% improved as assessed by the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (Chandler et al., Reference Chandler, Iosifescu, Pollack, Targum and Fava2010). If required, the screening period could be used to achieve an adequate duration of SSRI/SNRI treatment. Thus, in total, eligible patients had an inadequate response to 2–3 ADTs during the current episode. Permitted SSRIs were citalopram hydrobromide tablets (20 or 40 mg/day), escitalopram tablets (10 or 20 mg/day), fluoxetine capsules (20 or 40 mg/day), paroxetine controlled-release tablets (37.5 or 50 mg/day), and sertraline tablets (100, 150, or 200 mg/day); permitted SNRIs were duloxetine delayed-release capsules (40 or 60 mg/day) and venlafaxine extended-release capsules (75, 150, or 225 mg/day).

Patients were excluded if they had another primary DSM-5 diagnosis (specified disorders included schizophrenia and bipolar disorder); current DSM-5 personality disorder; suicidal ideation in the past 6 months or suicidal behaviour in the past 2 years; any clinically significant neurological or unstable medical condition; previously received adjunctive antipsychotic medication for ≥3 weeks during the current episode; previous exposure to brexpiprazole; or received new-onset psychotherapy within 42 days of screening or during the trial.

The trial consisted of a screening period, a 6–8-week acute treatment phase to identify patients who responded to ADT + brexpiprazole (Phase A), a 12-week stabilisation phase to stabilise patients on ADT + brexpiprazole (Phase B), a 26-week randomised double-blind parallel-group withdrawal phase (Phase C), and a safety follow-up (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Study design. ADT, antidepressant treatment; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression – Severity of illness; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder. aBlind applies to adjunctive treatment; patients continued on their current ADT, which was open-label throughout the study. bTitrated as follows: first week, 0.5 mg/day; second week, 1 mg/day; third week, 2 mg/day; fourth week onwards, 2–3 mg/day (flexible dose). cFlexible dose. dOne dose adjustment permitted. eSpecifically, history of inadequate response to 1–2 ADTs during the current episode, plus inadequate response to current ADT.

In Phase A, eligible patients continued their current ADT from screening (open-label), and brexpiprazole 2–3 mg/day was initiated (blinded to patients; dose titrated over 2–4 weeks). At Weeks 6 and 8, patients were evaluated for response using the following criteria (blinded to investigators): ≥50% reduction in Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score from baseline (Montgomery & Åsberg, Reference Montgomery and Åsberg1979), and Clinical Global Impression – Severity of illness (CGI-S) score of ≤3 (Guy, Reference Guy1976). Patients who met the response criteria at either visit immediately entered Phase B, whereas patients who did not meet the criteria by the Week 8 visit were discontinued from the trial.

In Phase B, eligible patients continued ADT (open-label) + brexpiprazole 2–3 mg/day (blinded to patients). Stability was assessed using the response criteria from Phase A (blinded to investigators); patients were required to meet these criteria for 12 consecutive weeks (three excursions were permitted, provided they were non-consecutive and not at the last visit of Phase B). In addition, the dose of ADT + brexpiprazole had to be stable for the last 4 weeks of Phase B. Patients who met the stability criteria entered Phase C, whereas patients who did not meet the criteria were discontinued from the trial.

In Phase C, eligible patients continued ADT (open-label) and were randomised (1:1) to continued adjunctive brexpiprazole 2–3 mg/day or a switch to adjunctive placebo. Randomised treatments were assigned using a computer-generated randomisation code provided by the sponsor and stratified by site (block size 4). Treatment assignments were blinded to patients, investigators, and sponsor personnel, including those involved in data analysis. The transition from Phase B to Phase C was not made evident to patients. Study drugs were taken orally once daily at the same time each day, without regard to meals. Brexpiprazole tablets and matching placebo tablets were provided by the sponsor, packaged in blister cards labelled with patient and compound identification codes. Patients were assessed for relapse (defined in the ‘Endpoints’ section) at 2-weekly visits for the first two visits and at 4-weekly visits thereafter. Patients who met criteria for relapse were immediately discontinued from the trial and received alternative depression treatment.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was time to relapse in Phase C, defined as meeting any of the following criteria, measured from randomisation and blinded to investigators: (1) at the same visit, ≥50% increase in MADRS total score from randomisation and CGI-S score ≥4; (2) hospitalisation for depression; (3) discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or worsening of depression; (4) active suicidality, defined as a score of ≥4 on MADRS item 10, an answer of “yes” on question 4 or 5 on the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), or an answer of “yes” to any of the questions on the Suicidal Behavior section of the C-SSRS (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Brown, Stanley, Brent, Yershova, Oquendo, Currier, Melvin, Greenhill, Shen and Mann2011).

Secondary endpoints were time to functional relapse in Phase C, proportion of patients meeting relapse criteria in Phase C, proportion of patients meeting remission criteria in Phase C, change in MADRS total score (which ranges from 0 [no depression] to 60 [very severe depression]) (Montgomery & Åsberg, Reference Montgomery and Åsberg1979), change in CGI-S score (which ranges from 1 [normal, not at all ill] to 7 [among the most extremely ill patients]) (Guy, Reference Guy1976), and change in Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) Mean and item scores (Sheehan & Sheehan, Reference Sheehan and Sheehan2008). The SDS is a measure of functional disability across three items – work/school (which is skipped if the patient is not currently attending work/school), social life, and family life – each scored from 0 (not at all disrupted) to 10 (extremely disrupted) (Sheehan & Sheehan, Reference Sheehan and Sheehan2008), where SDS Mean score is the mean of the two or three completed items, and SDS total score is the sum of the two or three completed items. Functional relapse was defined as meeting all the following criteria at a single visit: ≥30% increase in SDS Mean score from randomisation, at least one SDS item with a score ≥4, and SDS total score ≥7 (if 3 items scored) or ≥5 (if the work/school item was not scored). Remission was defined as MADRS total score ≤10.

Safety was assessed via treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), body weight, laboratory tests, vital signs, electrocardiograms (ECGs), the C-SSRS (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Brown, Stanley, Brent, Yershova, Oquendo, Currier, Melvin, Greenhill, Shen and Mann2011), and three extrapyramidal symptom rating scales: Simpson–Angus Scale (SAS) (Simpson & Angus, Reference Simpson and Angus1970), Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (Guy, Reference Guy1976), and Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS) (Barnes, Reference Barnes1989). A TEAE was defined as an adverse event that started after initiation of trial medication, or an adverse event that continued from baseline of a specific phase and became serious, worsened, trial drug-related, or resulted in death, discontinuation, or interruption/reduction of trial medication during the same phase. TEAEs were coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) preferred terms.

Statistical analysis

Time to relapse in Phase C was analysed in the efficacy sample, composed of all patients who took at least one dose of randomised study drug in Phase C. A two-sided log-rank test was used to test the differences in Kaplan–Meier survival curves. A 95% confidence interval (CI) for the hazard ratio (ADT + brexpiprazole vs. ADT + placebo) was calculated using a Cox proportional hazard model with treatment as the fixed effect. Patients who withdrew early from the trial without relapse or who were still in the trial at the end of Phase C (Week 46) were considered as censored observations at the discontinuation or completion date. Time to relapse was also analysed in the following subgroups: sex (male, female), race (White, all other races), age at Phase C baseline (i.e., at randomisation; <45 years, ≥45 years), and region (US, Europe).

Based on a prior randomised withdrawal trial of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination (Brunner et al., Reference Brunner, Tohen, Osuntokun, Landry and Thase2014), 104 relapse events were needed in the present trial to reach 95% power to test a hazard ratio of 0.49 at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. This corresponded to a Phase C randomisation target of approximately 450 patients and a Phase A enrolment target of approximately 1450 patients. The randomisation and enrolment targets were approximate; the only hard target was 104 relapse events.

Two interim analyses were performed by an independent data monitoring committee after approximately 50% and 75% of relapse events had occurred. To keep the overall significance level at 0.05, the two-sided alpha levels for the two interim analyses were set at 0.0031 and 0.018, respectively, leaving 0.044 for the final analysis. The interim analyses did not meet the stopping criteria, and the committee recommended to continue the trial.

For comparisons of time to functional relapse (secondary endpoint), a log-rank test was used, similar to the primary analysis of time to relapse.

In Phases A and B, mean rating scale score changes from baseline were analysed using descriptive statistics (observed cases). Baseline was defined as the first visit of Phase A; Phase B did not have a separate baseline and the baseline for Phase A was used. For Phase C, the last value from Phase B was used as the baseline value, termed ‘randomisation’ in this article. In Phase C, mean rating scale score changes from randomisation were analysed via two approaches: (1) last observation carried forward (LOCF) using an analysis of covariance model; and (2) exploratory analysis using a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) with fixed effects of treatment, pooled centre, visit, treatment–visit interaction, baseline value, and baseline–visit interaction as covariate, with an unstructured variance–covariance matrix structure. MMRM analyses are considered superior to LOCF analyses of covariance for longitudinal studies in terms of minimising biases (Siddiqui et al., Reference Siddiqui, Hung and O’Neill2009). Secondary endpoints were tested at a nominal 0.05 level with no adjustment for multiplicity.

After the trial began, two efficacy endpoints (mean change in SDS Mean score from randomisation to Week 46, and time to functional relapse) were reclassified from ‘key secondary endpoints’ to ‘secondary endpoints’ in the final statistical analysis plan (May 13, 2021) following a discussion with the US Food and Drug Administration, which concluded that these endpoints might be influenced by the anticipated dropout associated with the primary endpoint.

A safety sample was defined for each phase, composed of all patients who took at least one dose of study drug during that phase. Safety results are presented using descriptive statistics.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC).

Results

Patients

The trial began on July 13, 2018, and was terminated by the sponsor on June 15, 2022, upon reaching the target number of relapse events (106 relapse events were recorded; last follow-up date: July 13, 2022).

Phase A: single-blind acute treatment

Overall, 1149 patients were enrolled in Phase A (Fig. 2), of whom 811 (70.6%) were taking an SSRI and 338 (29.4%) were taking an SNRI. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Figure 2. Patient disposition. ADT, antidepressant treatment. aProtocol deviation (n = 12), non-compliance with study drug (n = 9), death (n = 1), physician decision (n = 1), other (n = 15). bNon-compliance with study drug (n = 9), protocol deviation (n = 9), physician decision (n = 6), pregnancy (n = 1), COVID-19 restrictions (n = 1), other (n = 11). cNon-compliance with study drug (n = 2), physician decision (n = 1), other (n = 6). dNon-compliance with study drug (n = 1), pregnancy (n = 1), other (n = 4).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline (Phases A and B) and at randomisation (Phase C)

ADT, antidepressant treatment; BMI, body mass index; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression – Severity of illness; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; SD, standard deviation; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale.

a Data are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

b Phase B did not have a separate baseline (baseline for Phase A was used).

Response criteria were met at Weeks 6, 7 or 8 by 777/1149 enrolled patients (67.6%), of whom 766 (66.7%) continued into Phase B. The remaining 383 patients (33.3%) discontinued the study, most commonly (>5%) due to not meeting response criteria (16.1%), or adverse events (7.1%) (Fig. 2). Mean brexpiprazole dose at the end of Week 6 was 2.2 mg (n = 997).

Phase B: single-blind stabilisation

Stabilisation criteria were met at Week 20 by 489/766 patients (63.8%), all of whom continued into Phase C. The remaining 277 patients (36.2%) discontinued the study, most commonly (>5%) due to not meeting stabilisation criteria (17.8%), adverse events (6.8%), or withdrawal of consent (6.1%) (Fig. 2). Mean brexpiprazole dose at the end of Week 20 was 2.3 mg (n = 504).

Phase C: randomised double-blind withdrawal

In total, 489 patients were randomised in Phase C: 240 to ADT + brexpiprazole and 249 to ADT + placebo. Demographic and clinical characteristics at randomisation were similar between treatment groups (Table 1). The study was completed by 251/489 (51.3%) patients: 120/240 (50.0%) on ADT + brexpiprazole and 131/249 (52.6%) on ADT + placebo. The most common reasons for discontinuation (>5%) overall in Phase C were relapse (21.7%), the sponsor terminating the study upon reaching the target number of relapse events (12.3%), and withdrawal of consent (5.1%) (Fig. 2). Mean brexpiprazole dose at the end of Week 46 was 2.2 mg (n = 116).

Efficacy

Phase A: single-blind acute treatment

Depression and functioning rating scale scores improved with ADT + brexpiprazole treatment during Phase A. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) change from Phase A baseline to Week 6 in MADRS total score was −17.7 (9.1) (n = 969) (Fig. 3a). The corresponding mean (SD) change in CGI-S score was −1.9 (1.2) (n = 969), and in SDS Mean score was −3.2 (2.5) (n = 882).

Figure 3. ( a – b ) Mean MADRS total score across Phases A and B. Values at Phase A Weeks 7 and 8 are for the subgroup of patients who did not meet response criteria at Week 6. ( c ) LS mean change from randomisation in mean MADRS total score in Phase C (efficacy sample). ADT, antidepressant treatment; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; LS, least squares; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures; OC, observed cases; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error.

Phase B: single-blind stabilisation

Among the 766 patients who responded in Phase A and entered Phase B, depression and functioning rating scale scores continued to improve throughout the 12-week stabilisation phase with ADT + brexpiprazole. The mean (SD) change from Phase A baseline to Week 20 in MADRS total score was −26.1 (6.3) (n = 496) (Fig. 3b). The corresponding mean (SD) change in CGI-S score was −3.1 (1.0) (n = 497), and in SDS Mean score was −5.0 (2.3) (n = 460).

Phase C: randomised double-blind withdrawal

One hundred and five relapse events were recorded in the efficacy sample; one additional relapse event occurred in a patient who was randomised but did not receive treatment in this phase. Time to relapse (primary endpoint) was similar between the ADT + brexpiprazole and ADT + placebo groups: median 63 days from randomisation in both groups (Fig. 4). The proportion of patients meeting relapse criteria during Phase C was also similar between treatment groups: 22.5% on ADT + brexpiprazole and 20.6% on ADT + placebo (p = 0.51) (Table 2). In the subgroup analyses by sex, race, age, and region, the 95% CIs of hazard ratios for time to relapse in each subgroup included 1, indicating no meaningful differences between ADT + brexpiprazole and ADT + placebo (data not shown).

Figure 4. Kaplan–Meier product limit plot of time to relapse from randomisation in Phase C (primary efficacy endpoint, efficacy sample). ADT, antidepressant treatment.

Table 2. Summary of efficacy endpoints in Phase C (efficacy sample)

ADT, antidepressant treatment; CI, confidence interval; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression – Severity of illness; LS, least squares; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures; SD, standard deviation; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; SE, standard error.

a Cox proportional hazard model. Hazard ratio <1 is in favour of ADT + brexpiprazole.

b Log-rank test.

c Chi-square test.

d MMRM.

Time to functional relapse was similar between treatment groups: median 36 days for ADT + brexpiprazole and 35 days for ADT + placebo. The proportion of patients meeting functional relapse criteria during Phase C was also similar between treatment groups: 33.9% on ADT + brexpiprazole and 30.0% on ADT + placebo (p = 0.31) (Table 2). Remission criteria were met by a similar proportion of patients at their last visit in both treatment groups: 72.1% on ADT + brexpiprazole and 72.9% on ADT + placebo (p = 0.85) (Table 2).

From randomisation to Week 46, MADRS total score changes were small, with no significant differences between treatment groups (Table 2, Fig. 3c [MMRM]; Supplementary Table S1 [LOCF]). Similarly, there were no significant differences between treatment groups in change from randomisation to Week 46 in CGI-S score, SDS Mean score, and SDS item scores (Table 2 [MMRM]; Supplementary Table S1 [LOCF]).

Safety

The incidences of TEAEs, serious TEAEs, and discontinuation due to TEAEs in each phase are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of treatment-emergent adverse events (safety sample)

ADT, antidepressant treatment; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

a Data are expressed as n (%).

b Most commonly (>1%) akathisia, n = 21 (1.8%).

c Most commonly (>1%) akathisia, n = 11 (1.4%).

d No TEAE led to discontinuation in >1% of patients.

e Cardiac arrest.

Phase A: single-blind acute treatment

TEAEs with an incidence ≥5% during Phase A (6–8 weeks) were headache (9.9%), akathisia (9.6%), somnolence (7.9%), insomnia (6.3%), nausea (5.6%), and increased appetite (5.3%). Most TEAEs in Phase A were mild or moderate in severity; severe TEAEs were reported by 3.2% of patients.

One death was reported in Phase A; this was the only death in the study. The patient, a 27-year-old White male taking citalopram + brexpiprazole, died of cardiac arrest on Day 12. The patient had a history of illicit drug use, but no history of cardiac disorder, and ECG measurements at screening and baseline were normal. The patient became ill after returning from a vacation during which he had not taken citalopram + brexpiprazole for 3–4 days. The death was considered by the investigator to be unrelated to study drug.

The mean (SD) weight change from Phase A baseline to Phase A last visit (up to 8 weeks) was + 1.2 (2.3) kg. The incidence of potentially clinically relevant weight gain (≥7%) at any visit in Phase A was 4.3% (48/1121), and the corresponding incidence of potentially clinically relevant weight loss (≥7%) was 0.8% (9/1121). In general, mean changes in laboratory parameters (including metabolic parameters), vital signs, and ECG findings over time were small and not clinically meaningful in all three phases (data not shown). Of note, the mean (SD) change in fasting triglycerides from Phase A baseline to Phase A last visit (up to 8 weeks) was + 18.9 (148.0) mg/dL.

The incidence of suicidal ideation as a TEAE was 0.3% (3/1136) in Phase A, and there was no indication of treatment-emergent suicidal behaviour as measured by the C-SSRS. Extrapyramidal symptom rating scale scores (SAS, AIMS, and BARS) showed little change from Phase A baseline to last visit of Phase A (all <0.1 points) (data not shown).

Phase B: single-blind stabilisation

TEAEs with an incidence ≥5% during Phase B (12 weeks) were increased weight (15.9%) and headache (5.4%). Most TEAEs in Phase B were mild or moderate in severity; severe TEAEs were reported by 2.6% of patients.

The mean (SD) weight change from Phase A baseline to Phase B last visit (up to 20 weeks) was + 2.2 (4.0) kg. The incidence of potentially clinically relevant weight gain (≥7%) at any visit in Phase B was 23.2% (173/745), and the corresponding incidence of potentially clinically relevant weight loss (≥7%) was 2.4% (18/745). The mean (SD) change in fasting triglycerides from Phase A baseline to Phase B last visit (up to 20 weeks) was + 14.1 (78.8) mg/dL.

The incidence of suicidal ideation as a TEAE was 0.5% (4/765) in Phase B. There was one TEAE of suicide attempt during Phase B; this was the only suicide attempt in the study. The patient consumed 20 over-the-counter sleeping pills in the evening; the next morning, the patient woke up at the normal time and in retrospect was glad that the suicide attempt did not work. The patient continued in the trial with no dose changes. On the C-SSRS, suicidal behaviour was reported by two patients in Phase B (0.3%), and an actual attempt, aborted attempt, and preparatory acts or behaviour were each reported in one patient (0.1%). Extrapyramidal symptom rating scale scores (SAS, AIMS, and BARS) showed little change from Phase A baseline to last visit of Phase B (all <0.1 points) (data not shown).

Phase C: randomised double-blind withdrawal

The incidences of TEAEs, serious TEAEs, and discontinuation due to TEAEs were similar between treatment groups in Phase C (26 weeks) (Table 3). The only TEAE with an incidence ≥5% in the ADT + brexpiprazole group during Phase C was increased weight (10.4%, vs. 5.2% in the ADT + placebo group). In the ADT + placebo group, headache also had incidence ≥5% during Phase C (5.6%). Most TEAEs in Phase C were mild or moderate in severity; severe TEAEs were reported by 1.7% of patients in the ADT + brexpiprazole group and 2.0% in the ADT + placebo group.

In Phase C, the mean (SD) weight change from randomisation to last visit (up to 26 weeks) was 0.0 (3.4) kg in the ADT + brexpiprazole group and −1.0 (3.7) kg in the ADT + placebo group. The incidence of potentially clinically relevant weight gain (≥7%) at any visit in Phase C was 5.5% (13/235) with ADT + brexpiprazole and 2.9% (7/243) with ADT + placebo. The corresponding incidence of potentially clinically relevant weight loss (≥7%) was 5.1% (12/235) with ADT + brexpiprazole and 7.8% (19/243) with ADT + placebo. In contrast to Phases A and B, fasting triglycerides decreased during Phase C: the mean (SD) change from randomisation to last visit (up to 26 weeks) was −5.9 (68.3) mg/dL in the ADT + brexpiprazole group and −15.8 (80.3) mg/dL in the ADT + placebo group.

The incidence of suicidal ideation as a TEAE in Phase C was 0% (0/240) with ADT + brexpiprazole and 0.4% (1/248) with ADT + placebo, and there was no indication of treatment-emergent suicidal behaviour as measured by the C-SSRS. Extrapyramidal symptom rating scale scores (SAS, AIMS, and BARS) showed little change from randomisation to last visit of Phase C (all <0.1 points) (data not shown).

Discussion

In this randomised withdrawal study, continued adjunctive brexpiprazole treatment did not differ from brexpiprazole withdrawal (i.e., switch to adjunctive placebo) on the primary endpoint of time to relapse. This may be attributed to the observed high rate of sustained response in both randomised groups. Regardless of whether patients continued adjunctive brexpiprazole or switched to adjunctive placebo in the randomised withdrawal phase (Phase C), approximately 80% of patients who were stabilised with ADT + brexpiprazole remained relapse free at their last visit (up to 26 weeks), and approximately 70% met remission criteria at their last visit.

Although no additional benefit of adjunctive brexpiprazole maintenance treatment was demonstrated versus brexpiprazole withdrawal, important improvements were observed in acutely ill patients treated with adjunctive brexpiprazole. Specifically, high rates of response (approximately two thirds of patients responded in Phase A) and stabilisation (approximately two thirds of patients who responded in Phase A became stable in Phase B) were observed, together with large mean improvements on depressive symptom and functioning rating scale scores, in line with previous short-term trials of ADT + brexpiprazole (Thase et al., Reference Thase, Youakim, Skuban, Hobart, Augustine, Zhang, McQuade, Carson, Nyilas, Sanchez and Eriksson2015a; Thase et al., Reference Thase, Youakim, Skuban, Hobart, Zhang, McQuade, Nyilas, Carson, Sanchez and Eriksson2015b; Hobart et al., Reference Hobart, Skuban, Zhang, Augustine, Brewer, Hefting, Sanchez and McQuade2018a; Hobart et al., Reference Hobart, Skuban, Zhang, Josiassen, Hefting, Augustine, Brewer, Sanchez and McQuade2018b; Thase et al., Reference Thase, Zhang, Weiss, Meehan and Hobart2019; Hobart et al., Reference Hobart, Zhang, Weiss, Meehan and Eriksson2019a). In Phase A, a mean 17.7-point improvement in MADRS total score was observed over 6 weeks – a meaningful improvement, especially in patients who have previously proven difficult to treat (Hudgens et al., Reference Hudgens, Floden, Blackowicz, Jamieson, Popova, Fedgchin, Drevets, Cooper, Lane and Singh2021; Turkoz et al., Reference Turkoz, Alphs, Singh, Jamieson, Daly, Shawi, Sheehan, Trivedi and Rush2021). Overall, Phase A and B data suggest that adjunctive brexpiprazole treatment is beneficial over up to 20 weeks in the majority of patients with inadequate response to ADT. Furthermore, rating scale changes were small in Phase C, indicating that early improvement of depressive symptoms and functioning was maintained in the majority of stabilised patients.

Two other adjunctive antipsychotics have been investigated in randomised withdrawal studies in patients with ‘treatment-resistant’ MDD, for which definitions vary (Rapaport et al., Reference Rapaport, Gharabawi, Canuso, Mahmoud, Keller, Bossie, Turkoz, Lasser, Loescher, Bouhours, Dunbar and Nemeroff2006; Brunner et al., Reference Brunner, Tohen, Osuntokun, Landry and Thase2014; McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Alsuwaidan, Baune, Berk, Demyttenaere, Goldberg, Gorwood, Ho, Kasper, Kennedy, Ly-Uson, Mansur, McAllister-Williams, Murrough, Nemeroff, Nierenberg, Rosenblat, Sanacora, Schatzberg, Shelton, Stahl, Trivedi, Vieta, Vinberg, Williams, Young and Maj2023). In the first study, adjunctive risperidone did not significantly differ from risperidone withdrawal (adjunctive placebo) on time to relapse (Rapaport et al., Reference Rapaport, Gharabawi, Canuso, Mahmoud, Keller, Bossie, Turkoz, Lasser, Loescher, Bouhours, Dunbar and Nemeroff2006). In the second study, olanzapine/fluoxetine combination demonstrated significantly longer time to relapse than olanzapine withdrawal (fluoxetine monotherapy) (Brunner et al., Reference Brunner, Tohen, Osuntokun, Landry and Thase2014). Although cross-trial comparisons must be made with caution due to differences in trial design, conduct, and population, it is notable that the relapse rate in the antipsychotic withdrawal arm was higher in the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination study (31.8% over 27 weeks) than in the present study (20.6% over 26 weeks). There are two sources of bias in the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination study that may have contributed to the increased relapse rate in the antipsychotic withdrawal arm. First, it is possible that the disappearance of characteristic side effects of olanzapine, notably sedation/somnolence (Eugene et al., Reference Eugene, Eugene, Masaik and Masiak2021), in the antipsychotic withdrawal arm may have resulted in awareness of treatment allocation and functional unblinding. Second, many antidepressants and antipsychotics are associated with withdrawal symptoms such as agitation and anxiety when discontinuing treatment, which may be considered a marker of relapse (Fava et al., Reference Fava, Gatti, Belaise, Guidi and Offidani2015; Fava et al., Reference Fava, Benasi, Lucente, Offidani, Cosci and Guidi2018; Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Schneider-Thoma, Siafis, Efthimiou, Bermpohl, Loncar, Neumann, Hasan, Heinz, Leucht and Gutwinski2022). Brexpiprazole has a longer steady-state half-life than olanzapine (91 vs. 30 hours) (Rexulti (brexpiprazole) Prescribing Information, 2023; Symbyax (olanzapine and fluoxetine) Prescribing Information, 2023; Callaghan et al., Reference Callaghan, Bergstrom, Ptak and Beasley1999), which may suggest that brexpiprazole is less likely to be associated with withdrawal symptoms than olanzapine (Andrade, Reference Andrade2022). Indeed, the only TEAE with incidence ≥5% in the brexpiprazole withdrawal group (and not in the continued brexpiprazole group) was headache, with incidence 5.6%.

Overall, safety data were consistent with earlier studies of longer-term brexpiprazole therapy (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Zhang, Skuban, Hobart, Weiss, Weiller and Thase2016; Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Weiller, Baker, Duffy, Gwin, Zhang and McQuade2018; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hefting, Lindsten, Josiassen and Hobart2019; Newcomer et al., Reference Newcomer, Eriksson, Zhang, Meehan and Weiss2019; Hobart et al., Reference Hobart, Zhang, Skuban, Brewer, Hefting, Sanchez and McQuade2019b) and indicate that longer-term treatment with adjunctive brexpiprazole is generally well tolerated. The most frequent TEAEs during acute treatment (headache, akathisia, somnolence, insomnia, nausea, and increased appetite) all had a reduced frequency in Phases B and C, indicating either that these events were transient, or were less common among patients who responded to acute treatment. The exception was weight gain, which was potentially clinically relevant in 23.2% of patients in Phase B, and which increased by a mean of 2.2 kg from baseline to end of Phase B, before stabilising in Phase C. In the olanzapine/fluoxetine combination study, 34.8% of patients had potentially clinically relevant weight gain prior to randomisation, and mean weight gain from baseline to the end of Phase B was 4.2 kg (Brunner et al., Reference Brunner, Tohen, Osuntokun, Landry and Thase2014).

One patient died during the present study (0.1%) – a comparable rate to that in prior longer-term studies of adjunctive brexpiprazole in MDD (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hefting, Lindsten, Josiassen and Hobart2019; Hobart et al., Reference Hobart, Zhang, Skuban, Brewer, Hefting, Sanchez and McQuade2019b). In general, the risk of suicidal behaviour is low in controlled studies of treatments for depression (Stone et al., Reference Stone, Laughren, Jones, Levenson, Holland, Hughes, Hammad, Temple and Rochester2009) and, consistent with this, there was one suicide attempt (0.1%) and two cases of suicidal behaviour (0.3%) in the present study. Rates of suicidal behaviour were also low (<1%) in the prior longer-term studies of adjunctive brexpiprazole (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Hefting, Lindsten, Josiassen and Hobart2019; Hobart et al., Reference Hobart, Zhang, Skuban, Brewer, Hefting, Sanchez and McQuade2019b).

Considering study limitations, participants received 18–20 weeks of adjunctive brexpiprazole therapy before randomisation; risk of relapse may have been higher if a shorter duration of adjunctive therapy was provided prior to randomisation. This study is also limited because there was no comparator arm in Phases A and B, meaning that the large benefits observed in these phases cannot be attributed to adjunctive brexpiprazole with certainty. In Phase C, there was no active comparator arm (such as another adjunctive antipsychotic) to validate the design and conduct of the trial. Relapse rates were low in the group randomised to brexpiprazole withdrawal, which may suggest that the study lacked sensitivity. Secondary outcomes in Phase C were not adjusted for multiplicity. The results of secondary outcomes might have been influenced by the dropout associated with the primary endpoint; for example, patients who experienced symptomatic relapse prior to functional relapse may be censored in the functional relapse analysis, leading to an underestimate of the time to functional relapse. The study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning that some visits were virtual and therefore without scheduled vital sign assessments; however, this was not thought to impact the efficacy results. Finally, as with all clinical trials, inclusion criteria limit the generalisability to a broader patient population.

In conclusion, while this study found no difference in time to relapse with continued adjunctive brexpiprazole versus brexpiprazole withdrawal, data from Phases A and B showed that depressive symptoms and functioning improved in patients with MDD and inadequate response to ADT who received adjunctive brexpiprazole, and data from Phase C showed that approximately 80% of stabilised patients remained relapse free at their last visit. MDD is a heterogeneous disease, and treatment approaches and decisions regarding treatment discontinuation should be individualised for each patient. Safety results were consistent with prior adjunctive brexpiprazole studies, supporting that adjunctive brexpiprazole therapy is generally well tolerated over up to 46 weeks. Furthermore, after 18–20 weeks of treatment, discontinuation of adjunctive brexpiprazole in stabilised patients with MDD was associated with minimal adverse withdrawal effects. This may be reassuring to clinicians given that this treatment duration is in line with normal clinical practice in the US, where the average treatment duration with an adjunctive antipsychotic is 14–17 weeks (Gerhard et al., Reference Gerhard, Stroup, Correll, Huang, Tan, Crystal and Olfson2018).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2024.32.

Acknowledgements

Writing support was provided by Chris Watling, PhD, and colleagues of Cambridge (a division of Prime, Knutsford, UK), funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. and H. Lundbeck A/S.

Author contributions

Roger S. McIntyre and Michael E. Thase contributed to the interpretation of data. Kripa Sundararajan, Saloni Behl and Na Jin contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. Nanco Hefting contributed to the conception and design of the study, and the interpretation of data. Claudette Brewer and Mary Hobart contributed to the conception and design of the study, carried out the study, and contributed to the interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Financial support

This work was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. (Princeton, NJ, USA) and H. Lundbeck A/S (Valby, Denmark). The sponsors were involved in the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing and reviewing of this article, and the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests

Roger S. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the Milken Institute; and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Neurawell, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, Abbvie, Atai Life Sciences. He is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp.

Kripa Sundararajan, Na Jin, Claudette Brewer, and Mary Hobart are full-time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. Saloni Behl was a full-time employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. at the time of this work.

Nanco Hefting is a full-time employee of H. Lundbeck A/S.

Michael E. Thase has served as an advisor/consultant for AbbVie (Allergan), Acadia, Alkermes, Axsome, Clexio, H. Lundbeck A/S, Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), Merck & Company Inc., Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sage Pharmaceuticals, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Takeda; he has received grant support from Acadia, Axsome, Clexio, Janssen, National Institute of Mental Health, Otsuka, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), and Takeda; and royalties from American Psychiatric Foundation, Guilford Publications, Herald House, Wolters Kluwer, and WW Norton & Company Inc; and his spouse is employed by Peloton Advantage, which does business with most major pharmaceutical companies.

Ethical statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The trial was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines and local regulatory requirements. The study protocol was approved by the governing institutional review board or independent ethics committee for each investigational site or country. All patients provided electronic informed consent prior to the start of the study, after the nature of the intervention and possible side effects had been fully explained.