The specific mechanics of the publishing system producing the key outputs of the Scottish Enlightenment – its processes, internal structure, key actors, centres, peripheries, and connections – are complex and difficult to isolate. These analytical complexities have more to do with the data and methods that historians have at their disposal, rather than a lack of comprehension of the complexities involved in eighteenth-century intellectual processes. Historical accounts frequently frame the Scottish Enlightenment as the result of increasingly more complex and efficient networks among publishers and authors, ultimately culminating in the emergence of an author-centred system towards the end of the century. Focusing specifically on publishers, some have concentrated primarily on the interconnected histories of single individuals or small groups, for example Warren McDougall’s biographical surveys of Charles Elliot and other partnerships.Footnote 1 Others have looked at larger collaborative structures, the monopolistic organizations known as the ‘congers’, focusing on the buying, selling, and protection of copyrights as the primary force behind book production.Footnote 2 James Raven has taken this a step further, and urged us to consider book production in commercial rather than intellectual terms.Footnote 3

This article describes the use of large-scale bibliographic data to extract and analyse the works, authors, and publishers of the Scottish Enlightenment. It argues that with careful preparation, bibliographic sources can be used to gain a broader view of a complex and dynamic phenomenon such as the publication history of an intellectual movement. The publisher networks of the Scottish Enlightenment formed a broad and interconnected system, one which, we argue, can be effectively examined using specific computational methods. Using such tools, we can trace the development and interplay between different works, and situate key publishers within a wider system. This allows us to move beyond thinking about single publishers (or small groups), and consider how a section of the system changed over time. In highlighting these interconnected links, we push back against previous scholarship which often depicted the relationship between London and Scottish publishers in a more straightforward, even adversarial tone. James Raven, for instance, describes the successful bookseller-publishers as the ‘real winners’ in this supposed struggle, highlighting their arrival in London from the countryside or Scotland with minimal capital and limited knowledge of the trade.Footnote 4 Our aim is to contribute to the existing literature by highlighting the evolving interaction between these distinct counterparts.

Importantly, our findings shed light on the noteworthy influence of subsequent editions of published works. These editions, surpassing the rate of new publications, prompt a reassessment of their impact on the evolving nature of intellectual output during the eighteenth century. This analysis reveals a dynamic and accumulative phenomenon shaped by a network of publishers in Edinburgh and London. We are also able to tie the evolving role of scientific printing in Scottish Enlightenment publishing to other genres and show how shifts in formats also highlight changes in the audience for these texts. Using network analysis, we illuminate the evolving roles of key publishers over time and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the forces behind the Scottish Enlightenment.

Taking an agnostic view which considers the features of individual publications (their authors, further editions, place of publication, and so forth) rather than a priori information, we show that our understanding of what comprises a Scottish Enlightenment text should be expanded to include a much wider range, such as grammars, instructional literature, and, above all, scientific works. These works have often been overlooked due to the reliance on contemporary eighteenth-century accounts of important authors. While previous work on Scottish Enlightenment publishing has taken the questions of formats, places, and genre into account, here we use quantitative tools to highlight patterns and to provide a bird’s-eye view. We show that the material circumstances – formats, new vs. subsequent editions, place of publication – are central to understanding the role of book history in making the Scottish Enlightenment.

In addition, we use network analysis to highlight two publisher categories: first, Scottish publishers whose subsequent editions were published by others in London, and second, Scottish publishers who set up in London and published themselves. To begin with, the central actors in this network were Edinburgh-based, with a handful of London-based collaborators. Over time, this model reversed so that the London part of the network became more cohesive. The data corroborates the role of London-based publisher Andrew Millar as the primary node. We argue that we should consider Millar’s exceptional position in relational terms: that he must be understood in the context of his wider network, taking into account a longer view of the publishing landscape both before and after his career. This approach allows us to understand not only the centrality of the most important actors but the connections between them and also to consider the role of lesser-known figures.

I

The emergence of a professional author in mid-eighteenth-century Britain went hand in hand with the birth of the copyright holding publisher and the overall development of printing networks. At the same time, the legal aspects of publishing and struggles against monopolies were in motion and the business itself was a somewhat wild terrain.Footnote 5 Take, as an example, David Hume, whose intellectual fame was crafted primarily in collaboration with the publishers Andrew Millar and William Strahan in London in the 1750s and 1760s.Footnote 6 Hume also worked together with a number of other publishers, especially in Edinburgh. After Hume’s rise to fame, his works were published and pirated in various locations, by a widening circle of individuals and organizations connected to the book trade. The popularity that Hume so desperately longed for since his youth was created not only by Millar and Strahan, but through a multitude of interactions and transformations within the global book trade.Footnote 7

Key to these interactions was an axis of printing stretching between London and Scotland. While it is undeniable that London played a significant role in fostering the Scottish Enlightenment through its printing industry, the network (or networks) between London and Scottish publishers has been relatively overlooked, despite a thorough analysis of publishing in Edinburgh and Glasgow by book historians.Footnote 8 The availability of archival sources, such as Hume’s correspondence, has shed some light on the journey of his works, starting from Edinburgh and making their way to London before attaining widespread recognition throughout Europe.Footnote 9 Yet despite our understanding of the specific trajectory followed by, say, Hume’s History of England, the broader scope of this seemingly logical pattern from the periphery to the centre remains unclear. How representative was Hume’s path in terms of other authors who initially published with Edinburgh publishers before joining larger establishments in London? To answer this, it is crucial to examine the overall London–Edinburgh dynamic instead of relying solely on individual cases drawn from archival sources.

The print explosion in early modern Britain undoubtedly fuelled the Scottish Enlightenment, with publishers playing a crucial role, yet one which is often overlooked in comparison to that of key authors. Our study builds upon Richard Sher’s influential work highlighting the importance of book history in defining the Scottish Enlightenment.Footnote 10 When discussing eighteenth-century British book history, other scholars often underline the legal struggles between London and Edinburgh booksellers, emphasizing the author’s role and the assumed emergence of the public domain through legislation.Footnote 11 Rather than focusing solely on legal struggles and the emergence of the public domain, Sher underlines the practical aspects of the British book trade.Footnote 12 Sher’s emphasis is on the sharebook system of copyright, where major publishers sold parts of copyrights and established their own trade practices.Footnote 13 Our findings indicate that practical developments fostered diverse modes of collaboration between Edinburgh and London, challenging the notion that the relationship was solely characterized by one-sided printing activities from London to Edinburgh. Another area which a computational approach can shed light is in the debate surrounding the key topic areas of the Scottish Enlightenment. While Sher’s definition of it differs from that of Roger Emerson and Paul Wood, who stress the foundational role of science, our data-driven study aligns with the latter’s view by supporting the notion that works of scientific improvement played a pivotal role in this era.Footnote 14

Given that our interest is the printed output of the Scottish Enlightenment, this article relies on bibliographic data. The chief source for this is the English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC), a dataset of over 480,000 records of known works published mostly in the English language or in the English-speaking world. Most book historians studying the eighteenth century, in one way or another, rely on explicit or implicit quantitative analyses of the ESTC. The ESTC’s publication as a dataset, beginning from 1980, made it possible to produce basic statistical analyses of the British book industry for the first time. The resource’s importance as data and the value of using statistics to highlight general patterns was recognized almost immediately, such as C. F Mitchell’s article looking at provincial printing, and Robin Alston’s early work using the ESTC as data.Footnote 15 Over the years, many studies have made arguments through a reliance on the statistical analysis of large-scale patterns in the ESTC, from general statistical surveys to analyses of foreign-language titles published in Britain, to specific aspects such as religious texts.Footnote 16 Our approach relies on ESTC data to reveal insights organically. It aims to continue setting a standard for the statistical utilization of ESTC metadata, confirming many points established through manual analysis, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of quantitative analysis based on metadata. Furthermore, our data-driven approach extends beyond the confines of the second half of the eighteenth century, resonating with similar observations made by scholars in different contexts.Footnote 17

Quantitative analysis has expanded beyond specialized fields like ‘cliometrics’ or ‘bibliometrics’, as historians increasingly utilize the data from the ESTC not only as a finding aid but also as a versatile tool for their research. While asserting that the ESTC is problematic as a data source, James Raven also relies on it for aspects of his work into the book trade.Footnote 18 In their introduction to the Edinburgh history of the book in Scotland, Stephen W. Brown and Warren McDougall carry out what they call a ‘bibliometric analysis’, which uses counts of printing places as evidence of patterns of Scottish publishing, as does Michael Moss in his analysis of Glasgow as a place of publication.Footnote 19 Elsewhere, Richard Sher used ESTC searches as the basis for a list of key books and publishers of the Scottish Enlightenment.Footnote 20 What these have in common is that the findings rely on edition counts, with arguments resting on, for example, the tallies per year of records in the ESTC for a given author, place of publication, or particular genre. While undeniably useful, these methods have some issues – they rely on the researcher knowing what to look for (for example through searches of a particular keyword), and they rely on data not necessarily fit for quantitative analysis.

II

The groundwork for the data-driven approach applied in this article has been laid by previous cleaning of the ‘raw’ ESTC data. The Computational History Group (COMHIS) at the University of Helsinki has extracted and harmonized the MARC records which make up the original ESTC data.Footnote 21 Information on authors, printers, publishers, booksellers, titles, years, and places of publication has been extracted, where available, from the MARC field 260 (imprint).Footnote 22

An explanation of two aspects of this enhanced ESTC data is crucial. To understand how we count shared publishing output, the distinction between what we term works (the harmonized record for a single authorial work, which includes reprints and translations) and editions (the record for a single printed text) must be made. The ESTC records multiple reprints and variations of the same work. Unlike earlier quantitative work which has generally used counts of editions in the ESTC as a way of measuring the Scottish publishing landscape, the COMHIS ESTC data links together multiple editions of the same work, allowing us to computationally examine more complicated and nuanced patterns of printing along geographic lines. Also important is that the record of book trade actors (publishers, printers, booksellers) and authors has been extracted from the imprint and harmonized, allowing for much more accurate representations of their partnerships and networks. Further information on this process and its value to bibliographical research has been published in previous papers by the COMHIS group.Footnote 23

It is worth noting that although the data available to us has undergone significant harmonizing, there are still some challenges that need to be addressed. First, the ESTC is not comprehensive, as James Raven and others have noted.Footnote 24 Furthermore, not all the geographic information found on imprints has been extracted and converted into structured data. For example, due to the practice of co-publishing, there may be a second place of publication (or place of selling) mentioned in the imprint, or it may contain ambiguous or partial addresses. This information has been recorded in the ESTC data but is ignored for the first analyses below. In addition, for simplicity’s sake, we confine the study to two cities (London and Edinburgh), rather than looking at all the output and links between England and Scotland. While Edinburgh was the primary place of publication for Scottish works, other Scottish cities grew in output over the eighteenth century. Brown and McDougall have shown that once government and legal printing is discounted, Glasgow may have already rivalled Edinburgh as a printing centre by the middle of the century.Footnote 25 England’s publishing was more centralized in London, though there were university and provincial printing centres in a number of other places, including Oxford, Cambridge, Bath, and others.Footnote 26 Dublin, too, was an important printing centre and the links between that city and Edinburgh are also ignored for the purposes of this investigation.Footnote 27

Publisher–author relationships, and their impact on the Scottish Enlightenment, have been studied in detail.Footnote 28 Sher’s definition of the Scottish Enlightenment concerns the people who made it happen.Footnote 29 He identified a set of 360 works by 125 authors seen as key to the period, taking as a starting point authors listed by some contemporary sources.Footnote 30 This kind of listing of relevant people is difficult. The task we set out to accomplish was to extend the list of authors, works, and publishers particularly relevant to what is termed the Scottish Enlightenment, in a data-driven, reproducible manner. For this, we needed additional sources of data, chiefly (1) author backgrounds and (2) a useful genre division of all works in the ESTC so that we could analyse and limit our corpus to those we deemed most relevant. To achieve (1), we merged a number of sources resulting in a non-exhaustive but broad list of Scottish authors. To do this, we first extracted all authors with Scotland listed as the place of birth from the online knowledge base Wikidata, resulting in a preliminary list of 592 names. To this, we added another 770 authors by manual annotation, taking as a starting point all authors with a first edition published in Edinburgh, after which we manually checked each name on the list, using online and scholarly resources such as the ODNB where possible to determine nationality or place of birth. We then cross-referenced this with a list of key Scottish authors published in Sher’s The Enlightenment and the book and added any missing names (which were relatively few), resulting in a total of 1,401 confirmed Scottish authors to work with, the basis from which we derive the data-driven canon. For (2), we have used state-of-the-art methods to automatically classify the works of the ESTC into a set of sensible, historically aware, genres.Footnote 31

With the datasets outlined above, we set out to construct a list of the key authors, works, and publishers of the Scottish Enlightenment. While acknowledging that such a list may not be exhaustive, our aim was to incorporate a broader spectrum of relevant works than traditional research methods would allow, enabling us to establish connections with temporal and geographic data concerning further editions and reprints. This process involved extracting books, authors, and publishers deemed most relevant to the Scottish Enlightenment, based on a set of quantitative criteria (see below). Having completed this, our next objective was to examine and analyse this dataset of the Scottish Enlightenment, encompassing the relevant authors, their significant texts, and the pivotal publishers and their inter-relationships.

III

Here we present a statistical overview of this data-driven canon, employing bibliographic data to examine its temporal patterns, publication formats, locations, and genres. This serves a dual purpose, combining descriptive elements to provide an overview of the scope and diversity of this body of work, while also fulfilling an analytical objective.

To construct the list of relevant authors, we took all authors who were (a) found in our ‘Scottish authors’ list described above and (b) had at least two works which were, first, of a relevant genreFootnote 32 and, second, had at least one further edition.Footnote 33 The rationale behind this was to only include authors who made ‘substantial’ contributions within the relevant genres. This resulted in 352 authors we deemed of potential relevance. With this list of authors, we took the list of their works which matched the criteria above (in the relevant genre, and at least one further edition). This gave us a list of 692 works, linked to a total of 3,715 editions.

This list should not be thought of as a replacement for a hand-curated approach. Instead, it is a way of benchmarking and supplementing it with a broader perspective. It also brings with it the benefit of transparency and reproducibility, and the potential to generalize and use the same approach to other subsets (Irish or American authors for example), which could then be comparable. It also makes it possible to establish a workflow whereby additional subsets of the data could be extracted, for example by adding or subtracting genres of interest, by splitting the data into different time periods, or indeed by tightening or loosening the criteria by which a work is included. In tandem with a traditional approach, we hope it may help to expand the notion of a ‘Scottish Enlightenment work’, and it makes available a dataset which can be used to investigate the specifics of the period in more detail, and which is also available to the scholarly community for critique.

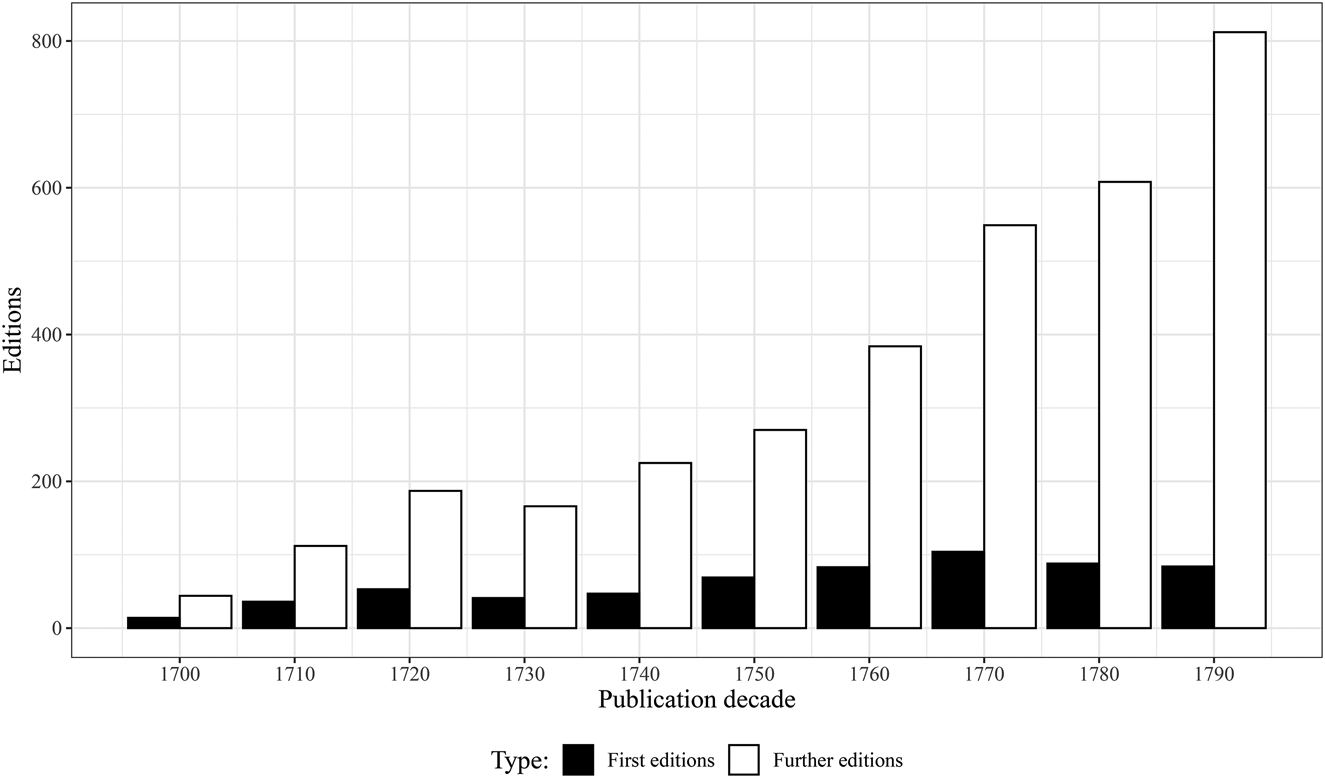

Looking at the temporal shape (Figure 1), a notable contrast between our list and existing research is the inclusion of earlier works, as our study begins at the beginning of 1700 (compared to Sher’s list starting in 1748). This deliberate choice allows us to examine the origins of publishing networks and the evolving dynamics between Edinburgh and London publishers over time.Footnote 34 We can analyse not only first editions but also subsequent editions. Figure 1 demonstrates that the overall growth of Scottish Enlightenment publishing aligns with the general trends of eighteenth-century printing, displaying a non-linear development of editions.Footnote 35 Notably, the 1720s witnessed a productive decade for new Scottish Enlightenment works, while the 1770s stands out as the only decade with over 100 new works before declining again. In contrast, subsequent editions (including reprints) show consistent growth (except for the 1720s) and a significant surge towards the end of the century. Based on these findings, we emphasize that these further editions and reprints, which play a vital role in disseminating Scottish Enlightenment ideas, should be considered central to understanding the era from a book history perspective.

Figure 1. Overview of the data-driven Scottish Enlightenment canon over time. Black bar plot shows the count of the new works each decade and white the number of subsequent editions.

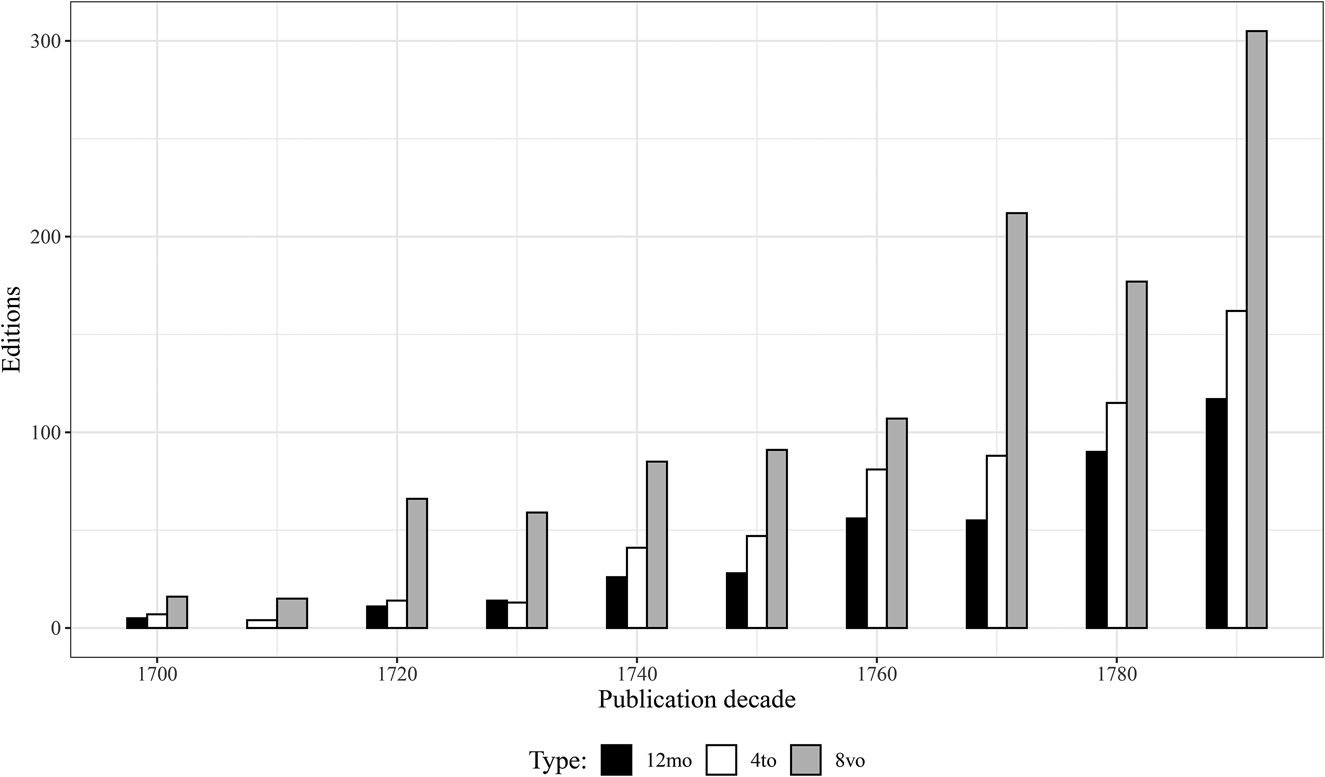

If we turn from the overall perspective of publishing the Scottish Enlightenment canon to the specific formats in which it was published, we notice several interesting aspects. Looking at the sheer volume of printing, it is obvious that the octavo size book (supported by duodecimo) is the leading format of the Scottish Enlightenment. In the discussion of printing the Scottish Enlightenment, much emphasis has quite rightly been placed on the question of changing formats within a publication history of a single work.Footnote 36 Tobias Smollett famously discussed quarto-worthy historians and Hume was very eager to push his publishers to understand that the large-paper quarto volume was the correct format to capture the dignity of his words.Footnote 37 What we see in Figure 2 is indeed that proportionally, the quarto size was used more as the format for first editions whereas smaller book sizes were often selected for second and further editions of what was first printed in quarto size. While it is evident that certain works hold greater value and recognition from both publishers and the public, our primary concern lies in the broader trajectory of printing development, which also encompasses the eventual inclusion of esteemed authors such as William Robertson and Hume. It is important to acknowledge that qualitative distinctions exist among these works, but our focus remains on the overarching progression of the printing landscape.

Figure 2. Chart showing the volume of second or later editions of works from the data-driven canon of the Scottish Enlightenment, showing the division between duodecimo (12mo), quarto (4to), and octavo (8vo) formats. The other important format, folio-sized works, are omitted here because in our subset there are very few for each decade.

The issue of book size extended beyond the prestige of scholarly individuals; it also involved the financial considerations for publishers. They had to carefully assess whether the cost of producing elegant quarto editions could be covered by their selling price, as well as the subsequent affordability and wider distribution of smaller-format editions. At the same time, this question of dissemination is crucial for the interplay between different locations and for the wider reading audience from the perspective of what books they could afford.Footnote 38

Figure 2 shows that the proportion of Scottish Enlightenment works which were second editions or later increased dramatically over the century. Additionally, large-paper volumes, of the type preferred by authors such as David Hume, dwindled. When this change in format is combined with the changes in genres of the Scottish Enlightenment discussed below, it becomes clear that Hume’s yearning for larger-format books is eventually overtaken by the needs of a wider audience. This analysis suggests that it is the voice of the publishers and the rather mundane questions of dissemination for their business models that takes the Scottish Enlightenment forward.

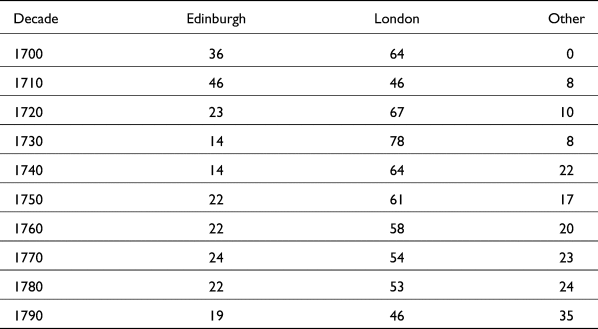

Studying the ESTC, it becomes apparent that London’s predominant role in publishing aligns with our expectations.Footnote 39 London’s primacy over eighteenth-century publishing, even that of Scottish authors, has been argued by many.Footnote 40 However, when we focus on publications by Scottish authors and study the publication places of the works and editions of our data-driven Scottish Enlightenment canon (Table 1), a more nuanced picture of London’s dominance is evident. Edinburgh does lose ground to London as a producer of Scottish Enlightenment work over time, though regains it somewhat over the century. Other places of publication also play a major role in disseminating the Scottish Enlightenment publications. Glasgow, as already mentioned, was a key place of publication for Scottish Enlightenment work, particularly further editions of existing works (of the 124 editions of our ‘canonical’ works printed in Glasgow, 108 are not first editions). Dublin, obviously, is an important place for publishing (and to a smaller extent, pirating) the Scottish Enlightenment and later in the century North American venues play a crucial role in its dissemination.Footnote 41 And, as previously mentioned, we should not ignore other towns in Scotland either. For understanding the dynamics of the Scottish Enlightenment, it is particularly important to grasp that we have two strong centres of intellectual production and by the outset this is not fully dominated by London-based operators, something which the section below on publisher modes of operation will confirm.

Table 1. Percentage proportion of ‘Scottish Enlightenment editions’ published per place and per decade. ‘Other’ category includes all other places besides Edinburgh and London. Numbers are rounded to the nearest whole number.

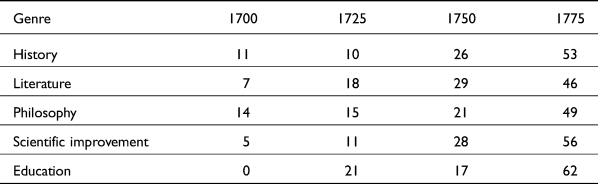

Previous scholarship of the Scottish Enlightenment has highlighted the high regard given to literary qualities by contemporaries, often at the expense of practical relevance. Our analysis in Table 2 brings to light the great significance of scientific improvement in the history of Scottish Enlightenment literature. Also apparent is the notable surge in works classified as education during later decades, suggesting an interconnectedness and mutual influence between practicality in natural and human sciences as they find their way to the core of Scottish Enlightenment printing over the century. Furthermore, literature and philosophy consistently maintain their prominence, indicating that the science of man, literature, and practical improvement are not only central to the Scottish Enlightenment but also intersect and evolve over time. This understanding elucidates how influential works such as David Hume’s Essays and treatises and Adam Smith’s contributions to the science of man and wealth of nations secured their central position within the evolving Scottish Enlightenment of the eighteenth century.

Table 2. Genre distribution of the data-driven canon of the Scottish Enlightenment, for each quarter of the eighteenth century.

These observations become even more apparent by closer examination of the count of each genre across quarters of the century (Table 3). Notably, our analysis highlights the increasing prominence of works of scientific improvement within the dataset. Philosophical works, particularly first editions, experience a decline over the course of the century. Historical works exhibit uneven development, declining in the second quarter but subsequently increasing in volume. Literature, on the other hand, assumes a pivotal role in the early stages, leading us to assert that figures such as James Thomson and other notable poets of the early eighteenth century should be included in a list of major works representing the Scottish Enlightenment.

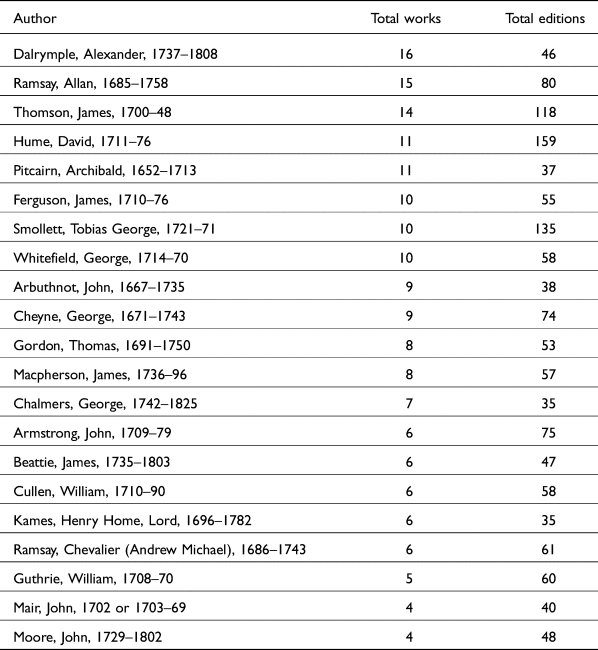

Table 3. Top authors of the data-driven canon of the Scottish Enlightenment. The genre of the author has been picked based on the most frequent genre across all included works.

Three authors stand apart from the others with respect to the number of editions. David Hume, as a versatile author making his fame with political essays and history, is a case apart judging by any metrics. In terms of popularity, the specialists, Smollett (literature and history) and Thomson (poetry) do very well too. By defining the works of the Scottish Enlightenment to include the earlier part of the century, the list also includes other poets besides Thomson, such as Robert Blair, John Armstrong, and Allan Ramsay. If we consider the early development of the Scottish Enlightenment, these authors should be seen as key.

Comparing the output of authors across different genres is also illuminating. Looking at scientific works, we find a large number of authors publishing fewer subsequent editions: no specialist in scientific work tops these lists. At the same time, many such authors make up a group of secondary importance. The names of William Buchan, William Cullen, George Cheyne, and James Ferguson are known eighteenth-century figures, but they are not often underlined when discussing Hume and other well-known champions of the Scottish Enlightenment. For the category of philosophy, one would not perhaps first think of Thomas Gordon (1691–1750) as part of the Scottish Enlightenment, but he indeed was a Scot and made significant contributions to the intellectual scene of his time with his work on Cato’s Letters and the like.Footnote 42

The observations show there is little to separate Scottish work written earlier in the century from what is considered the ‘heyday’ of the era. Furthermore, when considering publications, new editions, often printed in new cities, comprise a substantial portion of the canon, and their impact must also be taken into account. Finally, to reiterate, our methods shed light on the paramount importance of scientific publishing.

IV

A data-driven approach to the works and authors can also extend to publishers, printers, and booksellers. As established in the introduction, the publisher data have been extracted by COMHIS from the imprint field in the ESTC, and extensively harmonized.Footnote 43 To establish a list of key publishers is simply a matter of counting the number of publisher, bookseller, and printer appearances on the imprints of the 692 works (3,715 editions).

Doing so results in a list of 1,866 publishers, printers, and booksellers that appear on the imprints of those publications. Table 4 shows the top twenty of these (by number of editions of our ‘key works’ list) overall, plus counts broken down by genre. Alongside this, we list the count of first editions.

Table 4. Imprint counts for the ‘key Scottish works’, for the highest-ranked publishers/printers/booksellers by occurrences on imprints of these works. Number of first editions is given in parentheses.

Some of these Scottish Enlightenment publishers have been studied in great detail and our list includes Andrew Millar (1705–68), William Strahan (1715–85), and Thomas Cadell (1742–1802). Between them, Millar, Cadell, and Strahan published some of the most influential and important titles of the century, both Scottish and otherwise, including Hume’s History of England and Gibbon’s Decline and fall of the Roman Empire.

A second set of key individuals on the list operated businesses based primarily in Edinburgh but with extensions or partnerships in London. One who had worked with both Strahan and Millar was the Edinburgh-based Alexander Kincaid (1710–77). Kincaid formed several partnerships, first with Alexander Donaldson (1727–94) and later with John Bell (1745–1831), an important publisher who along with the aforementioned partnerships was known for publishing popular, cheap editions of literature classics.Footnote 44 Also in the top ten are two heirs to established publishing businesses (Thomas Cadell the Younger and Andrew Strahan).

What do these numbers tell us about publishing the Scottish Enlightenment? First of all, it is clear that the key publishers of the Scottish Enlightenment, in terms of genre, tended to publish diverse material. Clearly, the intertwining of the practical, theoretical (i.e. philosophical), and literary genres was something important to both authors and publishers. Additionally, some of those who feature prominently on this list are not usually thought of as so crucial. Two such figures are John Murray (1737–93), an Edinburgh-born, London-based publisher, and Charles Elliot (fl. 1771–90), based in Edinburgh, who purchased and succeeded to the business of William Sands and later opened a shop in London.Footnote 45 Elliot, as can be seen from Table 4, specialized in scientific (mostly medical) books and his contribution to the Scottish Enlightenment has been somewhat underappreciated.59

The table shows that many of these publishers mostly published later rather than first editions of Scottish works, meaning their contributions, too, have been overlooked. Some, for example William Davies, who was connected to the Scottish publishing milieu through his partnership with the Cadells, was involved almost exclusively with later editions of existing works, including six of William Robertson’s History of America and four editions of Buchan’s Domestic medicine.Footnote 46 Also on the list are members of two English, London-based publishing dynasties: Thomas Longman and Richard Baldwin. While we know that both these men collaborated and shared copies with Scottish publishers such as Andrew Millar, Table 4 clearly shows the extent to which they were publishing Scottish editions, albeit usually not first editions.

Almost one quarter of Andrew Millar’s works are first editions, making him, along with Alexander Kincaid and John Bell who have similar proportions, an outlier. Millar’s exceptionalism to the Edinburgh–London publishing network is striking and it will be further explored in the final section of this article. Thomas Cadell the Younger’s role demonstrates another type of publisher, the successor to an existing business. Both before and after his partnership with Davies, the younger Cadell seldom published first editions of these key works, evidently relying at first on his father’s copies rather than commissioning or seeking out new Scottish writing.

In the case of Millar, a notable pattern emerges throughout his publishing career, highlighting the increasing significance of scientific improvement as a primary category for his output. Interestingly, the composition of his publishing roster does not heavily rely on the influence of any particular author, as both the number of individual author works and their editions demonstrate a balanced and moderate distribution. However, one exception to this trend is James Thomson, whose impact on Millar’s early career is evident, particularly in the successful publication of literature volumes in the 1740s, where Millar’s name solely appears on the imprint as the publisher. When examining Millar’s contribution to the Scottish Enlightenment, a more nuanced perspective emerges, particularly in the 1750s. Notably, Millar demonstrates a strong inclination to publish works on history, literature, and scientific improvement under his own name, while religion and philosophy, especially philosophy, exhibit a higher prevalence of collaborative publishing. The analysis also reveals an interesting shift in Millar’s overall publishing strategy, as his career initially thrived in poetry publishing (with Thomson and Ramsay), but gradually transitioned to history and scientific improvement. Furthermore, religious works were prominent in the 1730s, particularly in titles where Millar’s name stands alone on the imprint, but religious printing gradually shifted to include works where other publisher names are also featured. When considering the broader context, the combined analysis of arts and the aforementioned trends provides valuable insights into Millar’s evolving publishing strategy. It serves as a testament to the shifting landscape of his career, with a notable transition from poetry to history and scientific improvement.

When we broaden our perspective from Millar to other publishers, other patterns can be seen. Many medical works published first by Alexander Kincaid in Edinburgh were later added to Millar’s roster of publications. William Strahan and Richard Baldwin are notable for publishing comparatively few philosophical works. Thomas Longman’s contribution was very much concentrated in scientific works, including many editions of James Ferguson’s practical scientific lectures. This table reiterates the case for the importance of lesser-known scientific works. A full eighty-three out of ninety-five editions published by Charles Elliot are scientific works, mostly medical, such as the nine editions of First lines of the practice of physic by the physician William Cullen, as well as multiple works by William Smellie and John Innes.

This group of twenty individuals in Table 4 taken together might be said to form the core of the networks responsible for printing the works of the Scottish Enlightenment. They were the centres of closely connected and constantly evolving networks of book trade actors. They can be found in a series of complex, ever-changing relationships, forming partnerships, and acting as parts of larger syndicates, as well as having changing relationships with different roles (for example an author and a publisher, or a publisher and a bookseller). There was tension between the London and Edinburgh axes of printing, due to conflicting legal claims about copyright, and even though most of the publishers were Scottish they were divided into ‘London’ and ‘Edinburgh’ groups. Therefore, we argue that the group serves as a useful starting point for an examination of the central axis of the London–Edinburgh publishing network, and as will be carried out in the next section, this network can be analysed computationally.

V

As we have highlighted, a significant portion of the dissemination of intellectual output during the Scottish Enlightenment relied on subsequent editions of works that were originally printed elsewhere and by different individuals. Publishers can be said to be linked not only by direct co-publishing of the same edition, but also through the way they collaborated on and published further editions of existing works. As was established in the introduction, we want to study the actual practice of forming the dynamics of the Scottish Enlightenment, taking seriously the difference between subsequent and new editions. This next section uses this principle to model further publisher networks.

This article suggests two competing models for Scottish publishers: first, Edinburgh-based Scottish publishers who distributed their works through different publishers to London, and second, Scottish publishers who also operated in London themselves. The publisher at the centre of much of this article, Andrew Millar, can be seen as an exemplary of the second model. Andrew Millar’s significance as a prominent publisher of the Scottish Enlightenment in London is widely recognized in book history. However, our focus lies not in recounting or adding to the contextualized narrative of Millar himself, but rather in examining how competing modes of operation developed over time. From our temporal analysis, we find that both modes of analysis were in place in the earliest period of study (1700–20), and by the time of Millar in the 1740s, the second mode of operation overtook the first. After Millar, we see a further transformation and these two operational models largely merge. In other words, the relationship between Edinburgh and London publishing cannot be summarized solely through the progression of Millar’s career, but through two wider patterns.

To understand the publishing landscape more fully, we needed a way to represent the complex structures of collaborations, partnerships, and groups of publishers responsible for the Scottish Enlightenment output. These relationships, of authors and publishers, but particularly of publishers to other publishers and booksellers, are important in assessing the impact and production of particular works. As with the various editions of the works themselves, these relationships spanned the Edinburgh–London axis. Many key publishers were Scottish but based in London, and many of the imprints include names of publishers based in both places.

Historians of the book have often referred to the web of relationships between publishers as networks, in the informal, metaphorical sense.Footnote 47 However, these networks can also be utilized as ‘a formalised abstraction that permits computational analysis’, through their representation as mathematical graphs.Footnote 48 A graph is an ideal structure for understanding these networks, and tools from network science allow us to move beyond simple counting numerically and consider flows, structures, centres, and peripheries, as well as the roles of individual actors within a larger whole.

In order to understand the central actors and structure of the publishing networks responsible for works which followed this Edinburgh-first-edition-later-London pattern, we constructed a co-occurrence network of book trade actors listed on the imprints of these texts. In a formal sense, a network is a mathematical graph consisting of entities (known as nodes, in this case, publishers and other book trade actors) and links (known as edges, here the co-occurrence on book imprints). Co-occurrence networks are a well-established technique used, for example, to understand patterns of influence by looking at co-authorship in academic fields, or co-citation studies, which aim to survey the structure and influential authors within a particular field.Footnote 49 The method has also been used specifically within the domain of print history: for example Michael Gavin’s work on seventeenth-century print networks as found in imprints, the ‘Shakeosphere’ project, and John Ladd’s work on co-occurrence networks drawn from early modern book dedications.Footnote 50 Using the same principle but different data, the ‘Six degrees of Francis Bacon’ project has used co-occurrence on ODNB entries to infer social relationships between early modern individuals.Footnote 51

This representation allows us to use methods and concepts from the fields of network science and Social Network Analysis. These are a set of techniques which help us, for example, to understand particularly important or central nodes, quantify the flow of works from nodes in one city to another, and highlight nodes which had particularly important structural roles, such as connecting two otherwise disconnected clusters together. Previous work has looked at the broader picture of networks derived from ESTC imprints, and analysed the overall network and centrality measurements and how they changed over time.Footnote 52 Here, the co-occurrence network is used in a more targeted, limited sense, to study the specific collaboration patterns of a group of key publishers, from the perspective of the links between two places of publication.

The resulting network model is best not thought of strictly as a ‘social network’, but rather that it maps those involved in book imprints together, as publishers, printers, and booksellers.Footnote 53 While many of its connected individuals will have known and collaborated with each other, we know that imprint information does not necessarily mean a genuine partnership. And of course, there are likely many other links between individuals involved in the book trade who knew each other but for a variety of reasons were never listed together on an imprint. Despite this, it is a useful tool to conceptualize the economic and social structure of the book trade from a particular perspective.

Having editions linked through a common ‘work’ ID means we can consider not just first Scottish editions, but also subsequent editions and reprints, which, as described above, took on particular patterns with respect to genres and formats. The spread of the ideas of the Scottish Enlightenment was, after all, contingent on the second, third, and subsequent publications of a work, particularly when those further editions meant a text and its ideas might gain a wider audience.

Of particular interest is the publication of first editions in Edinburgh with subsequent editions published or co-published in London. In total, the ESTC contains records for 23,133 distinct works (23,736 if we include tiesFootnote 54) published first in Edinburgh. Of these works, 703 (1,373 including ties) were published in London at some point afterward, a total of 1,790 editions. These London editions of Edinburgh works follow a similar pattern to the ESTC, increasing rapidly in volume during the eighteenth century. Many more works were co-published, meaning they were listed with an Edinburgh imprint but with London publishers and booksellers too, or vice versa.

Unsurprisingly, most editions published in this way were by Scottish authors. The most successful work by far published in this manner is Hume’s History of England, published first in Edinburgh in 1754, with sixty-six subsequent volumes and further editions published in London before the end of the century. Other notable works include Allan Ramsey’s pastoral comedy The gentle shepherd (published in Edinburgh in 1725, twenty-two subsequent editions in London), John Home’s tragedy, Douglas, and William Buchan’s Domestic medicine (Edinburgh in 1769, twenty-one subsequent editions). Not all of these texts are related to the Scottish Enlightenment. A number of English authors are also present (Samuel Johnson, Daniel Defoe, and David Garrick feature), as are some foreign authors (Jean Frederic Ostervald’s abridgement of the Bible, first published in Edinburgh in 1705, the Irish author Charles Macklin’s comedy The man of the world, first published in Edinburgh in 1781, and the Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant’s Genera of birds, published in Edinburgh in 1771 and with two editions in London afterwards). A notable pattern to works which traverse this Edinburgh–London route is a tendency to anti-Catholic or anti-Jacobite texts. These include The case of Mrs. Mary Catherine Cadiere, a work, translated from French, which recounts the trial of a Jesuit priest accused of the abuse of a woman in his charge, first published in Edinburgh and followed by many editions in London soon afterwards.Footnote 55 Other titles reflect more specific political tensions, particularly in the aftermath of the Jacobite rebellion in 1745. Several accounts of the rebellion make this list, mostly anti-Jacobite histories. Andrew Henderson’s The history of the rebellion is one published in Edinburgh in 1745, followed by several London editions, as well as Philip Dodderidge’s Some remarkable passages in the life of the Honourable Col. James Gardiner.Footnote 56

We are also interested in specifically modelling the network of individuals responsible for a flow of works from one city to another. We wanted to extract a subset of the data which had a particular pattern of a first edition published in Edinburgh, and subsequent editions published in London. A technique was developed where a link is drawn between two individuals if one is listed on the imprint of the first edition of a work in city A, and the other listed on a subsequent edition, but this time in city B (Figure 3). For each such case, a directed edge is drawn between the nodes, from the earlier to the later publisher, resulting in a network graph which can be analysed in a number of ways.

Figure 3. Workflow for turning the London–Edinburgh axis publisher data into a directed network.

This data allowed us to look more specifically at the information flow from Edinburgh to London. While in most cases, editions are published in the same city as the original, using this method we could extract a subset of works which were subsequently published in London following a first edition in Edinburgh, mirroring that of our exemplary work, David Hume’s Essays and treatises on several subjects. Doing so meant we could systematically study the works and authors which followed this same route. As we were interested in influence rather than editions printed long after the original, we only considered subsequent editions within twenty years of the first edition. To account for temporal changes, the network was drawn with twenty-year time slices of the data. We investigated four time slices in total, between 1700 and 1780. To account for co-publishing, where an edition was listed as published in London but with publishers with an Edinburgh address listed alongside them, we manually annotated the data and sorted publishers into their respective locations from the information on the imprints. By doing so, we could apply network analysis methods to the data and ultimately understand the structure and central figures in this particular pattern of publishing.

To analyse these networks, we look at their structure (whether the network was sparse or clustered together, for example), and at the most central figures within them (in network parlance known as centrality). A simple measurement of centrality is degree, which is a count of the connections attached to each node. As this network can be considered directed (the connection goes in the direction from the publisher on the first, Edinburgh, edition, to the publishers on the subsequent London editions), we can separate this into out-degree (individuals on the imprints of first Edinburgh editions later published in London) and in-degree (individuals who are listed on the largest number of subsequent London editions of Edinburgh works). We conceptualize these highest-degree nodes for each time slice as the key ‘exporters’ from Edinburgh (out-degree) and key ‘importers’ to London (in-degree). Importers and exporters are not meant in the specific business sense, but rather to distinguish between publishers involved in work later printed in London, and publishers working on those subsequent editions.

The resulting networks reveal aspects of the mechanics behind the Scottish Enlightenment, specifically the role of the links between Edinburgh and London and its impact on publishing output. These networks should be taken as a proxy for studying the structures of the publishing business and not as all-encompassing evidence of the historical reality, because they have been formed from information found on the imprints.

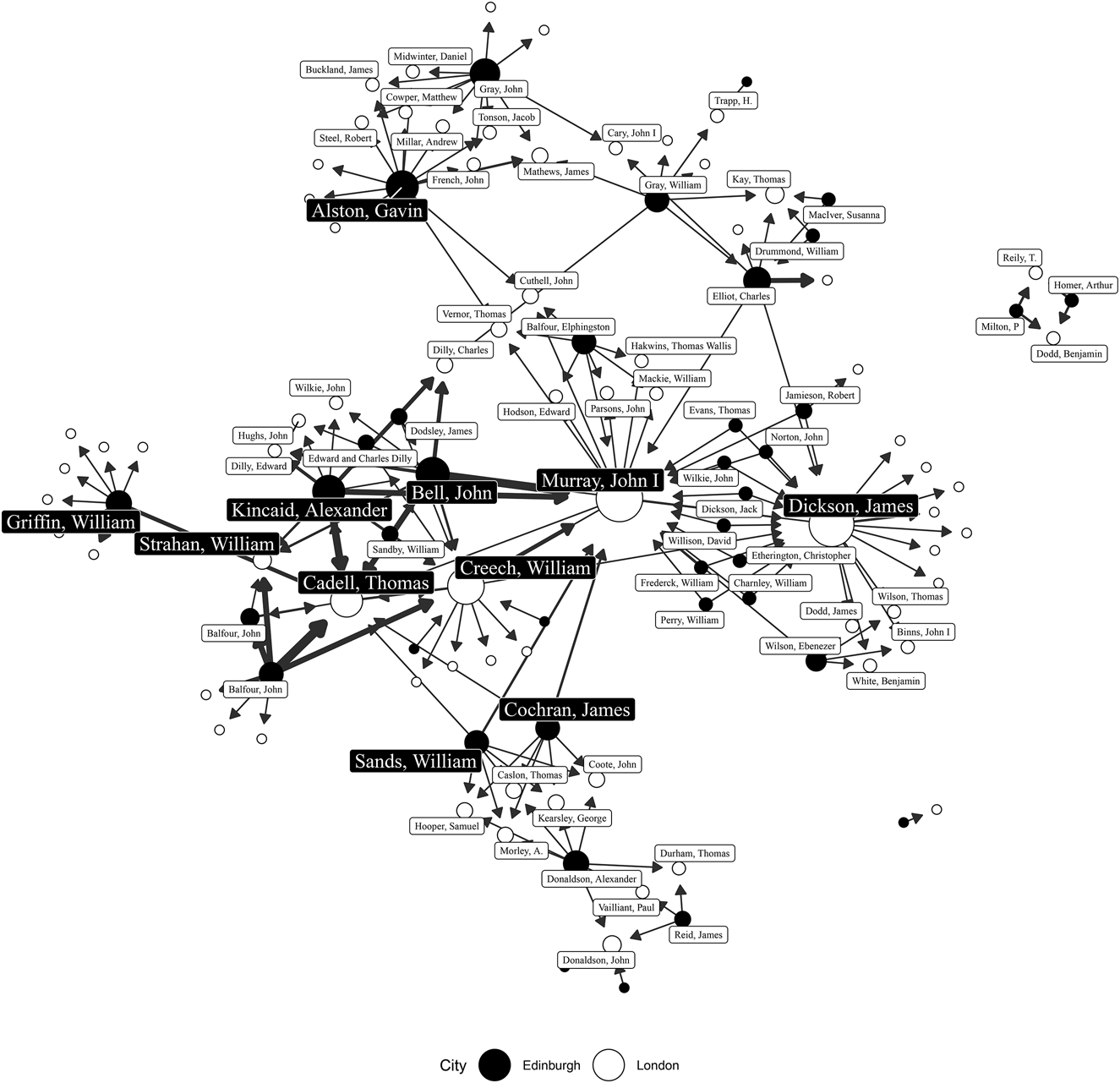

Focusing on each of these time slices we can see how the evolution of this particular Edinburgh–London pattern progresses. To illustrate the changing aspects of the network, we use a set of network diagrams. These visualizations serve several functions. First, each node is sized according to its total connections, meaning more connected or ‘important’ nodes appear larger in size. Next, the nodes are placed by an algorithm which attempts to place important nodes towards the centre of the diagram, and place closely connected groups of nodes together. Third, we have coloured each node by their most frequent city of publication (a black or white fill). Fourth, the thickness of the edge represents the weight of the connection (how many times the nodes/actors are connected). These are weighted by the number of subsequent editions, meaning that Edinburgh publishers who worked on works with many subsequent London editions are deemed more important by this metric. To reduce clutter, we have removed labels for nodes with just one connection, and highlighted some key individuals mentioned in the text.

A large, centrally placed node, for example, indicates that the publisher was widely connected, and not just to a particular subset. If that node is black, with mostly outgoing arrows, that indicates an important Edinburgh-based ‘exporter’. On the other hand, a white node with most incoming arrows indicates an important London-based importer of Edinburgh works. A single thick edge between a black and white node indicates a particularly important importer–exporter pair.

Studying the network mechanics of this subset of Scottish Enlightenment publishing, we find, essentially, two competing modes of operation. Looking at the interplay between these two modes sheds light on the Edinburgh–London publishing dynamics. The progression over time shows a shift from a model in which most of these titles were centred around publishers working in Edinburgh but the distribution in London is mostly scattered (an ‘exporter’ led model), to one where there are central and important players in London, systematically publishing key Edinburgh works (a model where the ‘importers’ are key). These four network slices highlight the changing nature of Scottish Enlightenment publishing. To begin with, it is driven by Edinburgh-based actors and a number of scattered London-based publishers. Over time, we see the emergence and rise of a London-based publisher – Andrew Millar – as the most central disseminator of such works, a role which after his death disperses to several publishers rather than remaining with one particularly central one. The stand-out author is David Hume, whose Edinburgh-first output had twenty-eight further editions in London within twenty years, mostly further editions of his History of England. Other authors with a similar profile are William Buchan, John Home, and Hugh Blair.

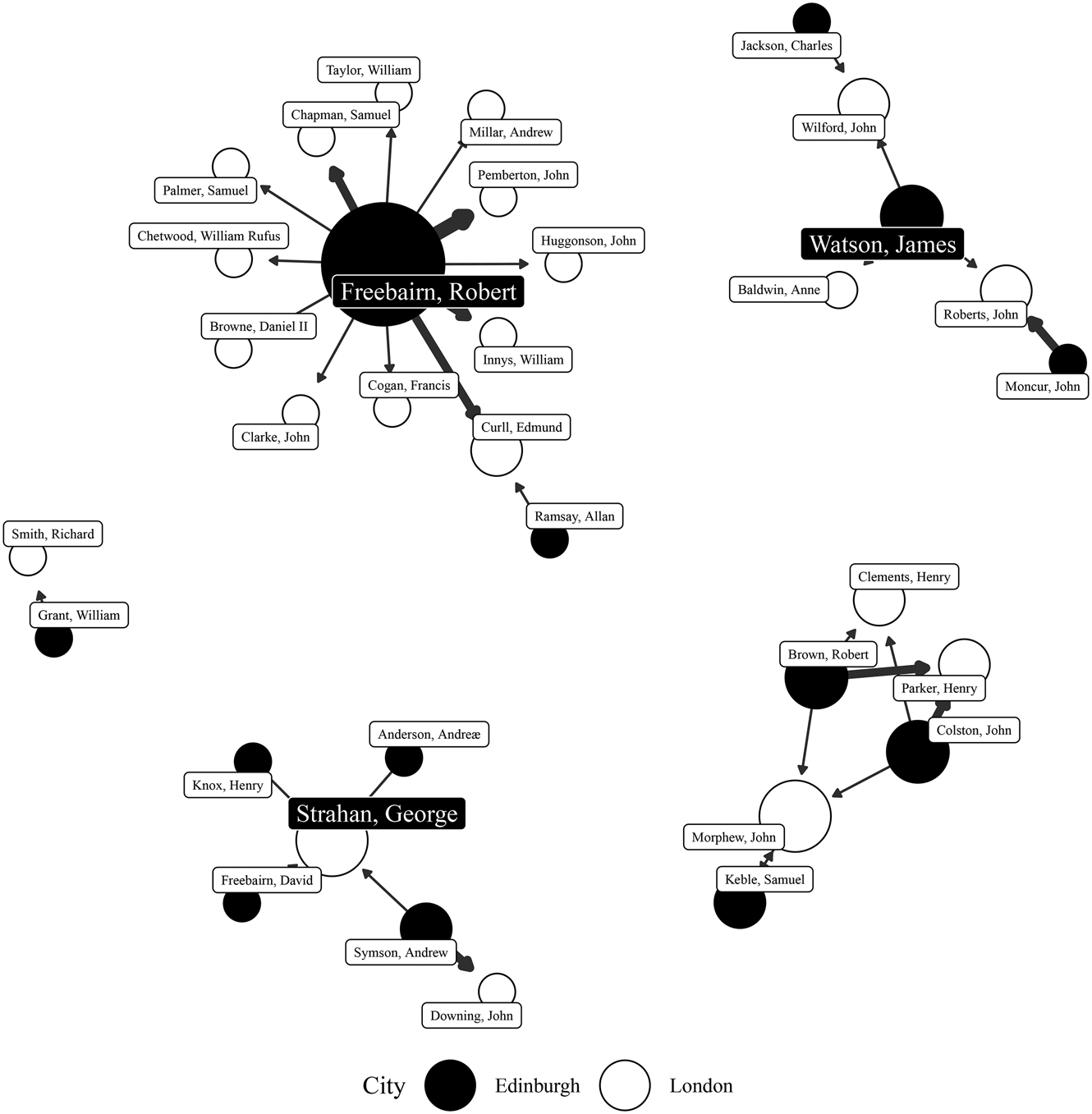

As well as this overall picture, we can look at the individual network diagrams to see how this publishing pattern changed over time. Between 1700 and 1720, we find a group of four disconnected components, several with a central Edinburgh figure connected to a number of distributed London-based publishers with a more minor role. Key is Robert Freebairn, the King’s printer for Scotland.Footnote 57 As is shown in Figure 4, Freebairn published works later picked up in London, for example The rudiments of the Latin tongue, published by him in 1714 and later by Millar and others, in London, in 1730. Similarly, James Watson (1664?–1722), as a representative of a business model of distribution of Scottish material from the Edinburgh to London market, is worth mentioning. He worked on law and religion, but also on Scottish topics ranging from literature, politics, science, and history, publishing also Abruthnot’s John Bull, and a number of important periodicals.Footnote 58 There is also one key London-based node: George Strahan, who published several subsequent editions of Edinburgh-first works. Strahan was also involved in the ‘Universal History’ venture of 1729.Footnote 59 For understanding the development of the London-based business model over time, the role of Strahan is crucial.

Figure 4. London–Edinburgh publishing dynamics 1700–20.

By comparison in the second ‘slice’, 1720–40, the importer/exporter network is mostly ‘connected’, meaning that there exists a path through the network between most nodes, or, in other words, we see the real beginnings of an Edinburgh–London network (Figure 5). Notably, there are now some key Edinburgh ‘exporters’ in the same role as Robert Freebairn above, indicated by the large black nodes. These are Thomas Ruddiman, the early eighteenth-century Scottish scholar and publisher, at one time employed by Freebairn;Footnote 60 the Edinburgh-based printer, Allan Ramsey, a poet who self-published several of his own works which were later popular in London; and William Hamilton, an important Edinburgh publisher. Hamilton worked on the first edition of Cadiere, which was later printed multiple times in London. Allan Ramsey’s edition of Poems was later printed by several others in London, including Millar. With respect to the business model represented in the earlier time slice by Strahan (that of London-based ‘importer’), this period can be seen as one of transition. We see clearly that most of the important or central nodes are Edinburgh-based publishers of first editions later published in London. One important exception to this is Andrew Millar. Even though Millar’s overall role was still minor at this stage, his placement in the centre of the graph and his connections to important nodes (Ruddiman, Ramsey, Mosman, and William Browne) are early clues to his growing importance within this network.

Figure 5. London–Edinburgh publishing dynamics 1720–40.

That which was clearly visible in terms of different modes of operation in 1720–40 is further established between 1740 and 1760 (Figure 6). There are still many important Scottish-based actors (John Balfour, Kincaid, Donaldson, Hamilton), but this network visualization clearly displays the centrality of Millar (and to a lesser extent his partner Thomas Cadell) as an ‘importer’ of works earlier published in Scotland. Millar publishes the subsequent editions of literary texts such as The Epigoniad (first published by Hamilton, Balfour, and Neill in Edinburgh in 1757, then in London by Millar in 1759) and John Home’s play Douglas (1757 in Edinburgh, 1764 in London by Millar), scientific and medical works by Francis Home and James Lind, and of course works by David Hume (Essays, moral and political and The history of Great Britain were both originally published in Edinburgh before Millar’s London editions). Furthermore, the network highlights the main suppliers of these works, including Kincaid and Donaldson, but also nodes which were seen in earlier time slices such as William Hamilton, William Gordon, and Charles Wright. Of note is the strong connection between Hamilton and Millar, something which has not traditionally been highlighted.

Figure 6. London–Edinburgh publishing dynamics 1740–60.

Millar is of course the epitome of the London-based business model. In this 1740–60 period, the London-based model had come to dominate, though it should be recognized that the Edinburgh-based model still operated, represented here particularly by Hamilton, Gordon, and Donaldson. These latter publishers continued their own businesses while at the same time working with Millar in London.

With this approach to studying Scottish Enlightenment publishing, we are inevitably distancing ourselves from such unfounded and perennial claims made for example by E. C. Mossner about there being a conspiracy of booksellers with respect to David Hume’s relationship with Edinburgh publishers and his History of England.Footnote 61 It seems that, despite tough opposition at times, most Edinburgh publishers were finding their ways to collaborate in the London market in legitimate business. There is no reason to undermine the efforts made by Edinburgh booksellers – it is this kind of rumour-based imaginative constructions by influential scholars that still haunt scholarship.Footnote 62

Between 1760 and 1780, the number of important London ‘importers’ increased: Thomas Cadell, William Strahan, William Creech, and most significantly John Murray. Murray took over the business of his partner William Sandby in 1768, operating from Fleet Street, and published many important scientific and medical works (Figure 7).Footnote 63 Murray’s connections here are because of his role as co-publisher: he is listed as the London publisher of a number of Edinburgh-printed books including William Perry’s The royal standard English dictionary, A philosophical analysis and illustration of some of Shakespeare’s remarkable characters by William Richardson (three subsequent editions published by Murray in London), John Innes’s A short description of the human muscles, and Hugh Blair’s Heads of the lectures on rhetorick, and belles lettres, in the University of Edinburgh (six subsequent editions in London). At the same time, the earlier business model is revived to a further glory, and we see new centres of Edinburgh-based publishers providing work to London. Key is the partnership of Kincaid and Bell, and to a lesser extent John Balfour, who published the first editions of works which would later be in the hands of Cadell, Creech, and Murray. There are other significant Edinburgh ‘clusters’: that of Donaldson, William Sands, and Cochran and the partnerships of James Dickson, Gavin Alston, and William Griffin. Most significantly, the monopoly that Millar had earlier does not pass to his successors, but this pattern of publishing is rather spread across several London-based publishers and groups.

Figure 7. London–Edinburgh publishing dynamics 1760–80.

VI

The nature and boundaries of the Scottish Enlightenment have long been a subject of debate. Throughout the twentieth century and beyond, discussions regarding the nature and impact of the Scottish Enlightenment were largely characterized by a general and broad approach. However, the early twenty-first century witnessed a shift in perspective with works like John Robertson’s Case for the Enlightenment, which emphasized the significance of political economy and propelled more targeted investigations into the Enlightenment discourse.Footnote 64 This development paved the way for focused examinations of the Scottish Enlightenment, and our research aligns with this trajectory by exploring the dynamic nature of the era through an analysis of its printing networks spanning the entire eighteenth century.Footnote 65

Our aim here was to see if a data-driven approach could provide a more complete narrative of the texts, authors, and phenomena behind the Scottish Enlightenment. The quantitative approach taken here meant we could move away from considering the Scottish Enlightenment as a single event, or as a series of discrete events, and rather as a continuum, the seeds of which were planted well before its supposed beginning, usually located between 1730 and 1750. Similarly, the list of relevant authors, works, and publishers can also be located on a continuum (from most to least relevant), in a transparent and reproducible way.

Our analysis confirms that the Scottish Enlightenment cannot be encapsulated by single individuals. Authors like Hume played pivotal roles in shaping the era through their influential works, yet their influence was not all-encompassing. Furthermore, we observe that while the number of first editions remained relatively constant throughout the century, the volume of publications grew through further editions from earlier decades. The cumulative nature of the Scottish Enlightenment, characterized by the ongoing reproduction of existing works and the increasing accessibility of these books in the eighteenth century, establishes its significance as a prominent intellectual movement that continues to influence society today. Therefore, it is important to recognize that the Scottish Enlightenment was not invented in the nineteenth century, despite the retrospective introduction of the term.

In examining Scottish Enlightenment publishing across various genres, we observe the growing prominence of science and education. This evolution goes beyond the confines of individual domains such as moral philosophy or political economy and includes the interplay between practical dimensions such as education and science, and the realms of literature and philosophy, particularly the science of man, which lie at the heart of the Scottish Enlightenment.

The driving force behind the intellectual output of the Scottish Enlightenment were the publishers, whose ever-changing nature facilitates the fusion of morals, literature, politics, science, and education. Using our methods allowed us to think beyond individual or multiple publishing partnerships and go beyond counting works or editions as a proxy for the importance and structure of the texts behind the Scottish Enlightenment. Instead, we can understand it in terms of the structures behind it, meaning its centres and peripheries, its forces, taking into consideration the flow of works through the network, and its dynamics, meaning the extent to which its forces changed and evolved over time, through the constantly changing networks of publishers responsible for the output.

Doing so has revealed a complicated structure of publishers, showing that the canon of Scottish Enlightenment texts can and perhaps should be extended. Additionally, we argue that to understand the publishing practices behind the Scottish Enlightenment, it is not enough to consider only fixed publishing collaborations, but we must take the evolving nature of these networks into account. Lastly, we consider the flow of works from Edinburgh to London, meaning that we can begin to model the spread or flow of information from Edinburgh to London and the wider world, getting at the heart of what it means to speak of a Scottish Enlightenment, which is, after all, contingent not only on the existence of printed intellectual work, but its wide dissemination. These methods go some way to represent the dynamics of the networks of publishers involved in the publication of the corpus of Scottish Enlightenment texts more faithfully, which were not a set of discrete partnerships but rather a process of continuous change.

While this study recognizes that the ESTC serves as an imperfect and partial proxy for the processes of the production of the books of the Scottish Enlightenment, it is nevertheless capable of making striking new interventions. The theoretical and methodological framework is twofold: first, the ‘bibliometric’ quantitative analysis allows us to make some general claims about the changes in the quality and quantity of links between publishers, authors, booksellers, and so forth and how this impacted the process of publishing the Scottish Enlightenment. Second, and perhaps more importantly, we intend these quantitative methods as useful tools to engage in what Jo Guldi has called ‘guided reading’ and ‘critical search’, allowing us to direct our humanistic enquiries to texts and authors which network analysis and other methods suggest were particularly important in their role as links between Edinburgh and London within the Scottish Enlightenment.Footnote 66 In this way, quantitative data and networks function not as evidence to make positivist claims about the history of English and Scottish publishing, but rather as sophisticated tools to filter and guide us to relevant texts, authors, and patterns, within a very large mass of data – particularly when combined with existing domain knowledge about key publishers and texts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank everyone who has collaborated with the Helsinki Computational History Group over the past decade to improve the ESTC data, which served as the basis for the Scottish Enlightenment data presented in this article.

Funding statement

Work for this article has been funded by the Research Council of Finland under Grants 1333716 and 1347706. The Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki has covered the Open Access fee.