Background

The Zeravshan River, which drains the north-western part of the Pamir and Tian-Shan Mountains (Figure 1), is one of the major rivers of Central Asia. From a palaeoanthropological perspective, the Zeravshan Valley is part of the Inner Asian Mountain Corridor (IAMC). The IAMC provided a refugium for human populations during periods of climatic oscillations and served as the major migration route during the Palaeolithic period (Glantz et al. Reference Glantz, Arsdale, Temirbekov and Beeton2018; Iovita et al. Reference Iovita, Varis, Namen, Cuthbertson, Taimagambetov and Miller2020). Such migrations are evinced by the Neanderthal remains at the sites of Teshik-Tash (approximately 130km south-west of the Zeravshan Valley) and Obi Rahmat, both in Uzbekistan. The northern part of the IAMC is the Altai Mountains, a home for both Denisovan and Neanderthal populations during the Middle Palaeolithic. The presence of the Initial Upper Palaeolithic (Kot et al. Reference Kot2022; Rybin et al. Reference Rybin, Belousova, Derevianko, Douka and Higham2023) in Uzbekistan and Altai suggests that modern humans may have also populated the region, making the IAMC a location where the three human metapopulations could have met and interacted during the Palaeolithic period.

Figure 1. Map showing major sites, including the two new sites studied in this project—Obi Borik and Soii Havzak (figure by authors & Sapir Ben-Haim).

Stratified Palaeolithic sites in the IAMC are rare, far apart and technologically diverse. Whether this diversity is a matter of small sample size or a real phenomenon demands further inquiry into the Palaeolithic of the region. In 2022, we initiated a survey in the eastern part of the Zeravshan Valley around the city of Panjakent, Tajikistan. During the fieldwork, several tributaries of the Zeravshan River were surveyed. Two stratified Palaeolithic sites were discovered—Obi Borik and Soii Havzak (Figure 1). Soii Havzak rockshelter was excavated during the 2023 season. Here, we present results of this excavation.

Soii Havzak site

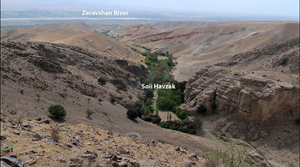

Soii Havzak is a small tributary of the Zeravshan River, about 10km north of Panjakent (Figure 2). The Soii Havzak site is a rockshelter/overhang carved into a cliff face about 40m above the stream (1165m above sea level; Figure 3A & C). The sediment that had accumulated under the overhang formed an extensive talus composed of rock debris and loessic and anthropogenic material sloping towards the lower terrace of the stream. Three trenches were excavated following the discovery of lithic artefacts on the slope (Figure 3A & B).

Figure 2. View to the south from the Soii Havzak gorge to the Zeravshan Valley (figure by authors).

Figure 3. A) photograph of the site and Soii Havzak stream, with trenches I, II and III marked; B) plan of the site; C) section of the gorge: 1: metamorphic rocks; 2: upper river terrace; 3: archaeological sediments and talus; 4: lower river terrace; D) trench I, southern wall: layer 1: topsoil, non-anthropogenic; layer 2: anthropogenic, fine-grained brownish sediments; layers 3 & 4: anthropogenic, fine-grained grey charcoal-rich sediments; layers 5–7: non-anthropogenic, slope sediments with angular stones of various sizes; layer 8: grey sediments, some ash; layer 9: anthropogenic, dark grey ash-rich fine-grained sediments; layer 10: slope sediments mixed with layer 9 (figure by authors, Marion Prevost & Omry Ganchrow).

Methodology and results

Trench I, located at the top of the sedimentological sequence, was excavated to a depth of 1.2m and yielded several in situ archaeological layers (Figures 3D & 4A). In total, 277 artefacts made of flint, metamorphic rocks (metasedimentary rocks, mostly slate of Silurian age) and quartz and hundreds of bones (weight = 2792g) were recovered. The uppermost archaeological layers 2–4 are composed of compact sediments rich in charcoal remains (Figure 4B) and contain several bones and lithic artefacts. The lithic assemblage is composed of small flakes, micro-debris and fragments, some of which represent resharpening and bladelet core maintenance (Figure 5D). A bladelet (Figure 5F) and a lightly retouched flake were found in layers 2–4. The assemblage composition suggests that these layers represent either Mesolithic or late Upper Palaeolithic occupations.

Figure 4. A) trench I, west view; B) flotation samples with charcoal from layer 3; C) bones from layer 9; D) finds from layer 9; E) scraper on metamorphic rock (figure by authors).

Figure 5. Lithic artefacts of flint: A) naturally backed blade; B) burin; C) flake; D) core tablet; E) blade; F) bladelet; G) distally crested blade; H) pseudo-kevallois flake (eclat débordant a dos limite); metamorphic rock: I) pointed blade; J–m) blades; N) discoidal core (figure by authors).

The next stage of occupation is represented by the lower part of layer 8 and layer 9. Layer 9 is an ashy layer that contains bones and artefacts (Figures 3C, 4C & D and 5A, B, C, E, I). Layer 10 likely represents the same occupation but is disturbed. The lithic assemblage contains flakes and blades with unprepared striking platforms. Several blade-core maintenance elements were found. Large numbers of flakes and fragments indicate on-site knapping; charcoal, ashes and burnt flints indicate the use of fire. The tool assemblage also includes several retouched flakes and blades and a burin (Figure 5B & I). The characteristics of this assemblage suggest an Upper Palaeolithic age. According to the density of finds, this occupation was considerably more intensive than that of layers 2–4 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Trench I's main archaeological characteristics. Amount of lithics (n = 277), charcoals (502g), bones (2792g) (figure by Marion Prevost).

Trenches II and III yielded 149 and 50 artefacts, respectively, in layers composed mostly of rock debris, loess and reworked loess. The artefacts are fresh, unrolled and unpatinated. These assemblages confirm that both bladelet and blade production were employed at the site (Figure 5J–M). Moreover, together with surface finds, the assemblage indicates that an earlier phase of occupation may have been present at the site. These finds include several elongated flakes with facetted striking platforms, Levallois products and discoidal and hierarchical surfaces cores (Figure 5H, J, K, N & Figure 4E), which hint at a human presence during the Middle Palaeolithic and/or Initial Upper Palaeolithic. Therefore, Soii Havzak rockshelter contains at least three phases of occupation—two Upper Palaeolithic stages found in situ in trench I and an earlier phase or phases of occupation evident from the surface and trenches II and III collections.

Conclusions

Although Soviet archaeologists initiated systematic Palaeolithic research in Central Asia during the late 1930s, this region is still relatively under explored. The Middle Palaeolithic is known from several sites in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan but is poorly dated. Some lithic assemblages (i.e. from Teshik-Tash, Kuturbulak and Anghilak, all three located in Uzbekistan) document the use of Levallois and discoidal technology (i.e. Nishiaki & Aripdjanov Reference Nishiaki and Aripdjanov2021). These flake-oriented Levallois and discoidal assemblages were often lumped together as a single ‘technocomplex’, whereas the blade-oriented assemblages characterised by the use of the Levallois convergent unidirectional method—such as at Obi-Rahmat and Khudji—have been thought to represent another variant of the Central Asian Middle Palaeolithic (Krivoshapkin et al. Reference Krivoshapkin, Viola, Chargynov, Krajcarz, Krajcarz, Fedorowicz, Shnaider and Kolobova2020; Nishiaki & Aripdjanov Reference Nishiaki and Aripdjanov2021). Whether these variants represent chrono-stratigraphic stages or behavioural variability is still unclear (Vishnyatsky Reference Vishnyatsky1999). The Upper Palaeolithic presence in the region is exceptionally scarce. Two major sites in the region, Samarkandskaya (Uzbekistan) and, especially, Shugnou (Tajikistan), are bladelet-dominated industries with presence of carinated pieces (Ranov et al. Reference Ranov, Kolobova and Krivoshapkin2012).

Future excavations at the Zeravshan Valley sites will address questions concerning the chronology and characteristics of the Middle Palaeolithic and Upper Palaeolithic human occupation in the IAMC. Specifically, the Soii Havzak rockshelter—one of the very few multilayered stratified Palaeolithic sites in Central Asia—provides a unique case for testing models on the Palaeolithic diversity in the region. Ongoing and future work at the site will entail detailed studies of the lithic and faunal assemblages and radiometric dating.

Funding statement

No funding agency supported this research.