Woke-washing is beginning to infect our industry. It’s polluting purpose. It’s putting in peril the very thing which offers us the opportunity to help tackle many of the world’s issues.—Alan Jope, Unilever CEO (Davies, Reference Davies2019)

For better, and often for worse, the rise of “Woke Capitalism” means big business is constantly undermining its own purpose by pursuing trendy social goals. Earlier this year Dutch airline KLM launched a campaign telling their customers to fly less. —Matthew Lesh, Adam Smith Institute (Lesh, Reference Lesh2019)

At the first Society for Business Ethics (SBE) annual meeting that I attended in 1997, Tom Dunfee presented his ideas on the marketplace of morality, which captured the new trends of social cause marketing and socially responsible investing (Dunfee, Reference Dunfee1998). More than twenty years later, we see robust evidence of consumers, employees, shareholders, and communities choosing firms for their positions on social issues (Aziz, Reference Aziz2020; Deloitte, 2019, 2021; US SIF, 2020). Never before have we seen so many firms demonstrating the concepts behind the marketplace of morality and, at the same time, being criticized for their engagement in social issues. More specifically, recent business initiatives in response to pressing social issues have garnered criticisms from a wide range of audiences for being “woke” or engaging in “woke washing,” with both terms used in derogatory ways. Woke, a term originally meant to signal awareness, especially in relation to social injustices and discrimination, is now also being used in a stigmatizing manner to label firms for inconsistencies between their corporate social initiatives (CSIs) and firm purpose, values, or practices.

For some, the “woke” labeling process may seem similar to other negative, stigmatizing labels associated with poor firm behavior, such as greenwashing or sweatshop labor (Marquis, Toffel, & Zhou, Reference Marquis, Toffel and Zhou2016). The difference between these labels and woke labeling, I argue, lies in the underlying values associated with the label. Sustainable operations and the humane treatment of labor are broadly endorsed by societies such that firms do not experience criticisms for being “green” or treating their labor fairly. A firm that is exceptionally green or treats its factory workers exceptionally well will not be the target of a boycott for being “too green” or “too humane.” For woke labeling, firms face a substantial group that rejects the underlying activities for falling outside the purpose of business (i.e., being “woke’). Unlike greenwashing or sweatshop labeling, the label of “woke” is being used by two opposing camps, and firms will suffer if they swing too far in either direction by being deemed as too committed to a social issue (i.e., “woke”) or not committed enough (i.e., “woke washing”). With woke labeling, firms must carefully strike a balance between two groups of critics.

The purpose of this presidential address is to consider the perceived inconsistencies that elicit scrutiny from critics of CSIs and then draw parallels to the potential inconsistencies in our own field with a goal of exploring when inconsistencies are morally problematic. I start with an examination of recent CSIs related to health (COVID-19) and social justice (Black Lives Matter; BLM) adopted by the Top 50 of the Fortune 500 companies and the various criticisms leveled against these firms. I focus on CSIs because, as I will explain, they are voluntary activities that address social issues but fall outside the main operations of the firm and are not required by law. The goal of this exploration is not only to note the widespread adoption of CSIs in response to recent social issues but also to examine the criticisms that firms receive for their initiatives. I observe that the criticisms center on inconsistencies between the CSIs and the firms’ practices, values, or objective. Critics who argue that the firms’ CSIs are inconsistent with the firms’ perceived purpose tend to use the terminology of woke, while those who argue that the firms’ CSIs are inconsistent with the firms’ perceived values or practices tend to use the terminology of woke washing. I will argue that when critics label firms as “woke” or “woke washing,” the label creates a stigma that can lead to boycotts, divestment, and other actions against the firm. I connect this process to our own field by considering inconsistencies in our teaching and organizations that could garner similar criticisms. After drawing parallels between inconsistencies in business and academia, I consider the moral implications of inconsistencies and end by considering how our field could respond to the stigmatization of CSIs and guard against the stigmatization of our own work.

RECENT CORPORATE SOCIAL INITIATIVES

CSIs are generally considered voluntary corporate activities that are aimed at improving or addressing a social or environmental issue (Hess, Rogovsky, & Dunfee, Reference Hess, Rogovsky and Dunfee2002; Hess & Warren, Reference Hess and Warren2008; Margolis & Walsh, Reference Margolis and Walsh2003). They typically entail a commitment of resources (products, services, volunteer time, cash) over a period of time. Often the initiatives involve a combination of resources. For example, Warby Parker’s CSI entails the donation of eyeglasses to someone in need for every purchase of eyeglasses and requires not only the donation of a good but also coordination and distribution systems for donations (Marquis & Villa, Reference Marquis and Villa2014). These initiatives are more involved than one-time cash contributions. Even if the initiative centers on cash, the funding reflects a long-term commitment tied to a specific program (e.g., development of a university center focused on social justice), not a general donation to an organization (e.g., unspecified donation to a university).

COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter

In preparation for this presidential address, I collected data on the CSIs related to COVID-19, a health issue, and BLM, a social justice movement, adopted by the fifty largest firms of the Fortune 500. These data were extracted from corporate websites and news sources. The data indicated that more than half of the organizations adopted CSIs for both social issues. For the Fortune Top 50, I found that 62 percent of firms adopted both COVID-19 and BLM CSIs, 34 percent of the firms adopted only COVID-19 initiatives, and 4 percent of the firms adopted no initiatives related to COVID-19 or BLM. These statistics indicate the widespread adoption of CSIs for both COVID-19 and BLM. Despite the prevalence of these initiatives, they have been criticized.

To better show the composition of these initiatives, I provide details for several CSIs and the criticisms that the firms received (Table 1). Though Table 1 is not exhaustive, it illustrates the nature of the CSIs and the types of issues that critics raise.

Table 1: Illustrations of Corporate Social Initiatives and Criticisms

Criticisms

The criticisms in Table 1 highlight inequities or injustices associated with the firms’ CSIs for both BLM and COVID-19, primarily from the vantage point of the “woke washing” perspective.

For BLM initiatives, the criticisms focus on how the initiatives that the firms adopt to promote social justice in their communities are incongruent with the state of social justice within their organizations. More specifically, critics noted how the community-based initiatives clashed with the firms’ treatment of their own employees in terms of both compensation (Walmart) and a lack of racial diversity in the upper echelons of the organizations (JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America).

For COVID-19 initiatives, firms are criticized for their special initiatives meant to rectify or address community issues while ignoring underlying firm practices that contribute to the problem. We see Amazon and Walmart criticized for not addressing employee safety, Alphabet for not addressing COVID-19 misinformation spread via YouTube, and big banks for not addressing firm practices, such as lending and waiving bank fees.

While these firms were being criticized for inconsistencies between their CSIs in relation to their other firm practices, another set of critics was calling for boycotts of these same firms, putting them on a list of the “Worst of the Worst” (American Conservative Values ETF, 2021a, 2021b) for supporting “woke” capitalism (O’Neil, Reference O‘Neil2021). The American Conservative Values ETF (2021a, 2021b) purposely excludes these specific firms from its investment portfolio for the types of CSIs highlighted in Table 1.

Although this sample of the Top 50 of the Fortune 500 is limited in a variety of ways, the purpose of this exploration of recent CSIs is to establish the popularity of these initiatives across social issues (health and social justice) as well as the criticisms that companies experience when they engage in such endeavors. It is important to note that criticisms of CSI are not limited to US firms nor tied only to COVID-19 and BLM initiatives. Recent criticisms of international firms, such as Unilever, Marks & Spencer, Sony, and BMW, focus on initiatives ranging from gay pride to women’s rights to the poor treatment of minorities (Jones, Reference Jones2019; Martel, Reference Martel2021; Shephard, Reference Shephard2020). Alongside these criticisms, the language of woke or woke washing has appeared (Brown, Reference Brown2021; Haggerty & Prior, Reference Haggerty and Prior2021; Martel, Reference Martel2021; Sumagaysay, Reference Sumagaysay2021), and in the next section, I review the use of these labels and subsequently explain how these labels are being used in a stigmatizing way.

STIGMATIZATION OF CORPORATE SOCIAL INITIATIVES

In this section, I review the definitions and usage of “woke” language in the academic literature and popular press. I discuss how the term is being used by two groups of critics for different reasons but how both groups use “woke” labeling to signal a lack of consistency. I end by linking the language to research on hypocrisy and stigmatization processes.

Definitions

Woke has recently been added to two major dictionaries. It means to be “self-aware, questioning the dominant paradigm and striving for something better” (Merriam-Webster, 2017) and “alert to racial or social discrimination and injustice” (Oxford English Dictionary, 2017). In a review of the origins of the terminology, the Oxford English Dictionary offers a New York Times definition that dates back to the 1960s: “to be well informed and up to date” (Kelley, Reference Kelley1962; Oxford English Dictionary, 2017). These definitions convey desirable qualities, so the negative connotation may seem surprising, but as a recent New York Times article explains, “these days, ‘woke’ is said with a sneer” (McWhorter, Reference McWhorter2021). Although woke can still be used as a compliment, others say the term has become “weaponized” (Shadijianova, Reference Shadijianova2021) and “toxic” (Luk, Reference Luk2021). To demonstrate this shift, we need only look back a couple years to see journalists using woke to praise companies, such as “How DOW Chemical Got Woke” (Green, Reference Green2019) and “Costco Is the Most ‘Woke’ Company Out There” (Sears, Reference Sears2019). Yet, in the last year, we see a shift in usage, where woke conveys a false sense of commitment to social ideals or undesirable social values. Today, the headlines read “Brands Gone Woke: 5 Risks of Performative Pride Allyship” (Martel, Reference Martel2021) and “Emmanuel Macron Warns France Is Becoming ‘Increasingly Racialised’ in Outburst against Woke Culture” (Samuel, Reference Samuel2021). The evolution of the term from praise to an insult or undesirable trait falls outside the focus of this address. Instead, I focus on the stigma that the label can now carry, how it affects CSIs, and how it could potentially affect our field.

Woke

The first group of critics label CSIs “woke” to convey that firms should not be engaged in specific social initiatives because the initiatives are not consistent with the firms’ purposes, which are infrequently defined but appear to align with shareholder primacy or, more broadly, capitalism (Berkowitz, Reference Berkowitz2021; Brown, Reference Brown2021; d’Abrera, Reference d’Abrera2019; Economist, 2021; Lesh, Reference Lesh2019; Olivastro, Reference Olivastro2021; Ramaswamy, Reference Ramaswamy2021; Rhodes, Reference Rhodes2021). For example, d’Abrera (Reference d’Abrera2019: 21), in his article “Get Woke, Go Broke,” describes woke capitalism as a “push for radical and aggressive new standards, principles and strategies that completely undermine the purpose of their core businesses.” Andrew Abela (Reference Abela2020), dean of the Busch School of Business at the Catholic University of America, explains, “In practice, ‘woke capital’ does little more than pay tribute to progressive causes through marketing and posturing. The problem for companies that play along is that the proponents of many progressive causes are hostile to free enterprise itself.” These critics may accuse firms of aligning with social issues that are beyond, if not antithetical to, the firms’ purposes. For instance, d’Abrera (Reference d’Abrera2019) discusses firms’ misguided gender equality initiatives, such as Target’s push for inclusive bathrooms in 2016, which are viewed as falling outside the purpose or goals of a business and demonstrate “woke capitalism” (21). By pursuing profits and not social causes, critics argue, firms will be able to improve social welfare. As Olivastro (Reference Olivastro2021) indicates, “success, not corporate wokeness, elevates the human condition.”

Woke Washing

The second group of critics uses the label “woke washing” to convey that the firms’ CSIs conflict with the rest of the firms’ business practices or values (Alix, Reference Alix2021; Davies, Reference Davies2019; Dowell & Jackson, Reference Dowell and Jackson2020; Jones, Reference Jones2019; Martel, Reference Martel2021). In contrast to the first group, this group of critics believes that the firms are not doing as much as they promised or that the firms’ practices conflict with the social initiatives. Thus these critics believe that the firms are pretending to be woke.

Although woke washing is associated with several different definitions in the academic literature, in general, its usage is meant to convey that a firm is presenting itself as being engaged in or concerned about social issues when some or all of its practices do not align with this presentation (Sobande, Reference Sobande2020; Vredenburg, Kapitan, Spry, & Kemper, Reference Vredenburg, Kapitan, Spry and Kemper2020). Because of this misalignment, critics claim that the firm’s efforts are superficial or inauthentic. The inconsistency is also highlighted in the practitioner literature, most recently in a Forbes article in which the author explained,

Woke-washing is a term used to define practices in business that provide the appearance of social consciousness without any of the substance. A woke-washed business could theoretically promote the opposite of racial equality within its walls while championing causes of social justice to the outside world (Howard, Reference Howard2021).

In some cases, the misalignment of practices to messaging does not need to occur. As some authors suggest, just an “unclear or indeterminate record” on social issues is enough to earn a firm the label of “woke washing” (Vredenburg et al., Reference Vredenburg, Kapitan, Spry and Kemper2020: 445).

The social justice aspect of the “woke washing” label extends beyond racial issues like those highlighted by the BLM movement to a broad range of inequalities related to gender, sexual preference, citizen rights, immigration, and economic need. For COVID-19 social initiatives, social justice criticisms focus on the mistreatment of workers, not sharing resources with the community, spreading inaccurate information, and unequal access to health initiatives.

Unlike the “woke” critics, who focus on the purpose of the firm or capitalism, the “woke washing” critics tend to focus on how the CSI aligns with other firm practices (e.g., daily business operations) or values (e.g., sustainability, justice, integrity). Perhaps beneath the criticisms regarding these inconsistencies lies a conception of the purpose of the firm that differs from the perception of the “woke” critics. For example, “woke washing” critics may conceive of a broader firm purpose that extends beyond financial performance to social performance, as expressed in stakeholder capitalism (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984). If the foundation of the “woke washing” critics’ claims lies in their conception of the firm’s purpose (e.g., stakeholder capitalism), however, the CSIs would not be the source of criticism because a critic who views the firm’s purpose as including social welfare would not scoff at a CSI that addresses a social issue; the critic would regard it as progress. Regardless of whether the purpose of the firm underlies “woke washing” critics’ perspective, their criticisms are squarely focused on inconsistencies between practices rather than on an explicit discussion of the firm’s purpose (e.g., stakeholder primacy).

Inconsistencies

While the labels of “woke” and “woke washing” seem very different at first glance, their criticisms share a common thread: a focus on inconsistencies. Firms that adopt CSIs that are not consistent with the firms’ purposes are labeled “woke,” and CSIs that are not consistent with the broader set of firm values or practices are labeled as “woke washing.” These are not minor inconsistencies. Critics view these inconsistencies as worthy of a spotlight and a tarnished firm identity. They rise to the level of stigmatizing claims of hypocrisy. Some authors have explicitly tied woke language to hypocrisy (Economist, 2021; Ritson, Reference Ritson2020; Sterbenk, Champlin, Windels, & Shelton, Reference Sterbenk, Champlin, Windels and Shelton2021). For instance, in an article on choosing CSIs, Argenti (Reference Argenti2020) asks, “Are you willing to put your money where your mouth is? If not, but you speak out any way you risk being seen as hypocritical or woke washing.” Next, I explain how perceptions of hypocrisy can be a catalyst in the stigmatization process.

Hypocrisy

A broad literature on hypocrisy ranges from psychology to organizational theory (Brunsson, Reference Brunsson1993; Cho, Laine, Roberts, & Rodrigue, Reference Cho, Laine, Roberts and Rodrigue2015; Jordan, Sommers, Bloom, & Rand, Reference Jordan, Sommers, Bloom and Rand2017; Kougiannou & Wallis, Reference Kougiannou and Wallis2020; Lewin & Warren, Reference Lewin and Warren2021; Wagner, Lutz, & Weitz, Reference Wagner, Lutz and Weitz2009; Warren, Scharding, Lewin, & Pandya, Reference Warren, Scharding, Lewin and Pandya2020). Wagner and colleagues (Reference Wagner, Lutz and Weitz2009: 79) focus on the organizational level of hypocrisy and define it “as the belief that a firm claims to be something that it is not.” They note that “organizations, like people, may be perceived as demonstrating hypocrisy when inconsistent information about their own statements and observed behaviors emerges” (79). Hypocrisy is problematic for organizations because it “erodes trust and encourages attacks upon legitimacy” (Kougiannou & Wallis, Reference Kougiannou and Wallis2020: 348). As I have explained with my colleagues in previous work, hypocrisy is not the same as straightforward lying because it also involves a form of moral signaling (Lewin & Warren, Reference Lewin and Warren2021; Warren et al., Reference Warren, Scharding, Lewin and Pandya2020). Empirical evidence indicates that hypocrisy elicits particularly strong negative reactions, including moral outrage (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Sommers, Bloom and Rand2017; Lewin & Warren, Reference Lewin and Warren2021; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Lutz and Weitz2009; Warren et al., Reference Warren, Scharding, Lewin and Pandya2020).

In the popular press, we see firms labeled hypocrites when they adopt CSIs that are misaligned with the firms’ practices or values. For example, Apple, Nike, Adidas, Spotify, and L’Oreal were accused of hypocrisy for adopting initiatives supporting BLM while their corporate boards had no Black members (Ritson, Reference Ritson2020). Similarly, claims of hypocrisy were aimed at Amazon’s support for BLM when it resisted the disclosure of pay-gap data, which was important information for exposing racial disparities in pay (Sumagaysay, Reference Sumagaysay2021), as well as at firms that use advertisements to promote gender equality while the firms’ activities do not align with the messaging (Sterbenk et al., Reference Sterbenk, Champlin, Windels and Shelton2021). Thus the inconsistencies between CSIs and the firm’s purpose, values, or practices, which receive labels of “woke” or “woke washing,” elicit claims of hypocrisy from the organizational audience. The moral component of hypocrisy will be examined later in the address, but first I will relate the labeling of a firm as “woke” or “woke washing” to stigmatization processes.

Stigmatization Processes

As Goffman (Reference Goffman1963: 3) explains, stigma is “an attribute that is deeply discrediting” and that conveys being “tainted” and “discounted.” It is a way of differentiating people or things. In this section, I argue that labeling a firm as “woke” or claiming that it engages in “woke washing” is meant to discredit the firm and thereby create a stigma that elicits backlash from stakeholders.

The organizational literature includes a broad range of events that may cause organizational stigma, such as financial scandals, bankruptcies, accidents, publication of corruption indices, and product defects (Hudson & Okhuysen, Reference Hudson and Okhuysen2009; Sutton & Callahan, Reference Sutton and Callahan1987; Warren, Reference Warren2007; Warren & Laufer, Reference Warren and Laufer2009). Firms also may experience stigma based upon core aspects of the business operations, such as the stigmas associated with certain industries (men’s bathhouses, tobacco, weapons, alcohol, gambling) (Grougiou, Dedoulis, & Leventis, Reference Grougiou, Dedoulis and Leventis2016; Hudson & Okhuysen, Reference Hudson and Okhuysen2009; Oh, Bae, & Kim, Reference Oh, Bae and Kim2017). Much of the management literature focuses on the strategies that organizations use to manage the negative effects of stigma, including the use of CSIs as defense mechanisms against stigma (Grougiou et al., Reference Grougiou, Dedoulis and Leventis2016; Hudson & Okhuysen, Reference Hudson and Okhuysen2009; Waldron, Navis, & Fisher, Reference Waldron, Navis and Fisher2013). Little research, however, has considered CSIs as sources for stigma (for an exception, see Tracey and Phillips’s [Reference Tracey and Phillips2016] examination of stigma associated with an initiative supporting migrant workers).

The initial process of stigmatization at the organizational level has been outlined by Sutton and Callahan (Reference Sutton and Callahan1987), who conducted research on firms facing bankruptcy. Their model starts with the discovery of an unfavorable event by the organizational audience, such as financial difficulty. This leads to perceptions of a discredited and spoiled image. From the spoiled image, several reactions occur, which include disengagement by organizational audience members (Sutton & Callahan, Reference Sutton and Callahan1987).

While the shift from labeling to audience disengagement may seem sudden, Link and Phelan (Reference Link and Phelan2001: 370) explain how a label for an undesirable attribute becomes all-encompassing and leads to discrimination and isolation:

Incumbents are thought to “be” the thing they are labeled. For example, some people speak of persons as being “epileptics” or “schizophrenics” rather than describing them as having epilepsy or schizophrenia.… In this component of the stigma process, the labeled person experiences status loss and discrimination.… The linking of labels to undesirable attributes … become[s] the rationale for believing that negatively labeled persons are fundamentally different from those who don’t share the label—different types of people.

In the context of woke or woke washing, a firm does not simply have a CSI supporting BLM or gay pride that is regarded as woke or suggests woke washing. Rather, the firm, as a whole, is regarded as woke or woke washed. This shift from a label for a particular initiative to a label for the whole firm is demonstrated by lists of firms that are regarded as either woke or woke washed and the calls for action, such as boycotts and divestment, against those organizations (Berkowitz, Reference Berkowitz2021; Black Lives Matter: Greenlist, 2021; Brown, Reference Brown2021; d’Abrera, Reference d’Abrera2019; Economist, 2021).

The stigmatization process described by Link and Phelan (Reference Link and Phelan2001) is nicely demonstrated in the logic of a PR News article by Torossian (Reference Torossian2019) that focuses on the dangers of woke washing and gay pride month:

Pride has become a prime example of the woke washing trend. Brands from Listerine to Chipotle sport rainbow branding during June.…

When a brand is choosing a side on a political issue, it ultimately is choosing to alienate 50 percent of the population that is on the other side of the issue. Global, billion-dollar companies like Nike are able to take the negative attention that comes from something like the Colin Kaepernick campaign. Nike is an outlier.…

Most brands can’t afford to lose half the population or suffer the loss in profits that comes from a boycott. By choosing not to engage in political debates brands may lose out on a small amount of media attention or support from a very vocal subset of people. In addition, they avoid the backlash that is bound to come from the other side of the debate.

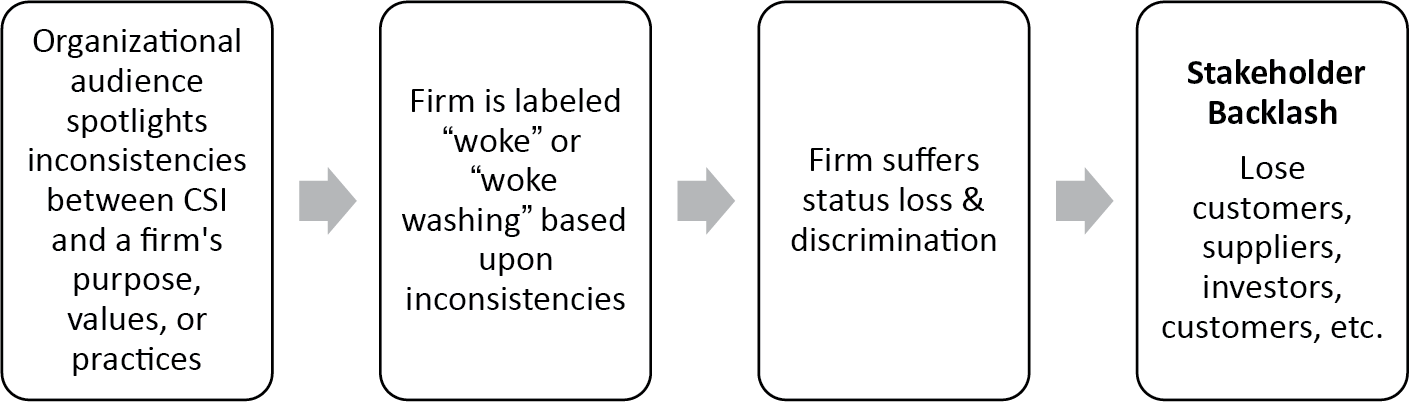

To summarize, when firms are labeled as “woke” or “woke washing” because of a CSI, the firms suffer status loss and discrimination and then experience stakeholder backlash, which may entail losing customers, suppliers, and investors. In Figure 1, I summarize the stigmatization process that firms experience once their CSIs are labeled “woke” or “woke washing.”

Figure 1: Corporate Social Initiative Stigmatization Process

For reasons I outline in the next section, it is important to take note of the trends unfolding with CSIs because we are not only invested in these initiatives but also should realize how our field could experience a similar labeling process.

ARE BUSINESS ETHICISTS WOKE OR WOKE WASHING?

Some may wonder why members of our field would be concerned about the balancing act that corporations face. Others may consider the “woke” labeling a fad that will pass with time. I suggest that, as a field, we should be engaged in this discussion for at least two broad reasons. First, our field helped spawn these CSIs, and by including them in our course materials and researching them, we implicitly promote them, so we should acknowledge our responsibility for their quality and purpose. Second, I argue that our field could easily suffer the same criticisms leveled against firms and their CSIs. Many critics who use woke language are already targeting the university system as the cause of “woke capitalism.” The Economist asserts that “wokeness” originated in elite universities (Economist, 2021), and Ramaswamy (Reference Ramaswamy2021: 228) similarly claims that “diversity is here now. And it’s spreading its woke tendrils from the seminar rooms of the ivory tower to the boardrooms of corporate America.” As I will discuss, several notable attacks on university courses and values have occurred in the past year.

In this section, I highlight several areas of inconsistency between the values and practices of our field by focusing on our pedagogy and our organizations. More specifically, I consider both how we analyze business cases and how the particular subset of the values that we integrate into our courses could elicit criticisms of woke or woke washing. I also explain how the practices of our organizations—professional and universities—could be considered inconsistent with our espoused values and objectives.

Pedagogy

Cases

One of the earliest and most frequently taught CSI cases focuses on Merck’s decision to develop and donate a treatment for river blindness (Murphy, Reference Murphy1991). During a normal semester, we may include Merck’s classic case in our syllabi alongside several other examples of CSIs, such as those adopted by Warby Parker and Patagonia (Marquis & Villa, Reference Marquis and Villa2014; Reinhardt, Casadesus-Masanell, & Barley, Reference Reinhardt, Casadesus-Masanell and Barley2014). By shining a spotlight on these business choices, our cases serve as exemplars for good business, shaping the set of possible avenues students may pursue when they are managers, and thereby we perpetuate CSIs. If we believe that these CSIs are of value and demonstrate progress in business practices, then should we speak out when they are criticized? At the very least, it seems we should defend impactful CSIs from “woke” labeling and perhaps develop clear guidelines for those that may be regarded as woke washing.

Courses

Beyond our teaching cases, business ethics courses could themselves be regarded as misaligned with the purposes, values, or practices of business schools, much like CSIs are viewed to be misaligned with firms’ purposes, values, or practices. Those who started the field and spent substantial time arguing for the legitimacy of conversations about ethics in business schools may feel as though they already successfully defeated the claims that business ethics courses are not aligned with the purpose of a business school education. New critics, however, could argue that business ethics courses have veered too far from shareholder primacy, market systems, and capitalism (i.e., woke). In contrast, criticisms may arise from a second group of critics—the socially conscious students who argue that we have not done enough. At the extreme, some may argue that the mere existence of a business ethics course within a business school education is a form of woke washing because they deem fundamental business practices taught in our foundational courses (those in accounting, finance, and marketing) to be morally problematic.

Second, they may note that we analyze business cases to develop ethical reasoning but that we do not fully research the internal operations and business dealings that occur outside the details of the case. Do we read the Glassdoor reviews from employees to understand if a case on diversity reflects the firm’s broader operation? Do we review all of the firm’s environmental records before we teach a case on green initiatives? We give a snapshot of a firm’s operations without fully researching the context of every business scenario, which means our course content could be inconsistent with the practices of the broader organization.

Inconsistencies within our courses may extend beyond a particular teaching case to the range of values that we incorporate into our courses, as some students may argue that we are ignoring their views. Recently, ethics-related courses are being questioned for not fully capturing the values of the broader communities that the universities serve. This past spring, Boise State University temporarily suspended fifty-two sections of the mandatory Diversity and Ethics course due to students reporting feelings of humiliation and degradation for their beliefs and values during a discussion involving capitalism, economics, and racial inequality (Gluckman, Reference Gluckman2021). Thus we are seeing a course on diversity and ethics, which focuses on the inclusion of diverse perspectives, being criticized for not being inclusive of (or for marginalizing) certain beliefs and values. The school hired a law firm to investigate and found that the claims were unsubstantiated, so the course was reinstated. State lawmakers, however, have targeted Boise State University classes and initiatives that promote social justice, a practice that is happening in other US states (American Association of University Professors, 2021; Gluckman, Reference Gluckman2021). In a business ethics course, these restrictions would broadly hinder the discussion of social justice topics, which could include topics such as the gender wage gap, supply chain labor practices, and racial bias in algorithms. For example, legislation would restrict the discussion of inequality and workers, such as the oppression of Uighurs, a minority Muslim population who work in Chinese factories producing goods for international firms (see Shephard, Reference Shephard2020). Worldwide, governments are proposing ways to restrict discussions surrounding a broad set of concepts related to discrimination that threaten to create tension between societal groups (Onishi & Meheut, Reference Onishi and Meheut2021; Sachs, Reference Sachs2021). At the same time, employers are receiving similar criticisms for the content of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) training (Chow, Phillips, Lowery, & Unzueta, Reference Chow, Phillips, Lowery and Unzueta2021; Damore, Reference Damore2017; Ramaswamy, Reference Ramaswamy2021).

What does it mean to teach “inclusive” ethics courses, and which values need to be reflected in the syllabus? Should an ethics course incorporate the values of the broader community if the broader community incorporates discriminatory perspectives (racism, sexism, xenophobia)? If we include the broader spectrum of values, such as extreme perspectives of racial supremacy, we need to be mindful of how this inclusion affects the education that individuals receive. Selvanathan and Leidner (Reference Selvanathan and Leidner2021) recently published the results of three studies that examined the normalization of the Alt-Right movement, which promotes a homogenous society for white people. The authors experimentally manipulated Gallup Poll data regarding the public’s acceptability of the Alt-Right and found that reporting higher public acceptability of the Alt-Right perspective led study participants to more positive reactions toward the movement. Thus conveying that a particular set of values is popular could lead to positive reactions and acceptance.

In response to the criticisms of value-laden discourse at work, some employers are being praised for not allowing employees to speak about personal values at work. For example, Basecamp’s CEO adopted a firm policy that restricts discussion of social or political topics (Hackett, Reference Hackett2021). In a related move, Coinbase’s CEO, Brian Armstrong, adopted a firm policy that explicitly restricts involvement in social and political issues as well as related communication in the workplace (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2020a). Due to resistance from employees, Coinbase offered unhappy employees a package to leave the company, and at least sixty employees took the package (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2020b).

Avoiding discussion of social issues is not an option for a business ethics course. We must strike a balance in the topics that we cover in our classes, and we cannot simply offer our students a package when they dislike the discussion of required coursework. While our coursework needs to address the broad range of ethical values in our communities, we also must be mindful of how we present these ideas—not so wide that discriminatory views are legitimized as valid positions in our communities and workplaces, but not so narrow that we miss the range of views and values held by our community.

Next, I consider how we espouse certain values and objectives for business organizations but may not reflect these values in our own organizations and practices.

Organizations

If you look at the objectives of the SBE, we state that we are interested in promoting the study of business ethics, improving teaching, and providing “a forum in which moral, legal, empirical, and philosophical issues of business ethics may be openly discussed and analyzed” (Society for Business Ethics, 2021b). In doing so, we hope to “develop and maintain a friendly and cooperative relationship among teachers, researchers, and practitioners in the field of business and organizational ethics” (Society for Business Ethics, 2021b). These objectives suggest that we will be welcoming of a wide set of ideas from a broad group of individuals. Although the objectives do not address barriers to the promotion of ideas or limitations in terms of access to our organizations, it is assumed that to strengthen our scholarship and teaching, all ideas should be considered, wherever they originate. In addition, if you look at our published research, we purport to care about such ideals as justice, equality, and the pursuit of virtues for businesses. Do we promote justice, equality, and virtuous practices within our own organizations (our universities, professional organizations, and business communities)? How do we know we are welcoming to a broad set of individuals and ideas?

Cutting-edge thought on business ethics could exist anywhere in the world, but our membership is oriented toward specific geographic regions with specific ethnic groups. If we look at the history of the SBE’s Board of Directors (Society for Business Ethics, 2021a), we see a pattern that is demographically homogenous, much like the composition of corporate boards of directors (Terjesen & Sealy, Reference Terjesen and Sealy2016). The SBE certainly had more women serving in leadership roles than corporations do (I am the ninth female SBE president in thirty years), but we see little variation in geographic and racial diversity (Society for Business Ethics, 2021a). We work within academic organizations and business communities that are similarly homogenous along dimensions such as race and gender. Woke critics would take issue with my attention to specific demographic categories. As Ramaswamy (Reference Ramaswamy2021: 216) explains, “wokeness sacrifices true diversity, diversity of thought, so that skin-deep symbols of diversity like race and gender can thrive.”

If we want to conceptualize diversity in terms of thought, as suggested by Ramaswamy (Reference Ramaswamy2021), then what steps are we taking as members of those communities to advocate for equal access based upon ability and thoughts, without bias? What steps are we taking to clear pathways for scholars who are not currently part of our existing social networks? DiTomaso’s (Reference DiTomaso2013) research indicates that racial inequality arises more so from preferential treatment by whites toward others in their social network than from overt racism. How are we working to move beyond our social networks to include new people in our academic communities to achieve diversity of thought?

One purpose of a presidential address is to inform our members of the difficulties our own organization faces and provide an outlook for the future. Hopefully, our members note recent shifts in our organization that involve concerted efforts by everyone to think more broadly about the composition of the board (in terms of both the balance of disciplinary backgrounds and demographics, including geography). During my time on the SBE Board, the organization has taken several steps to improve our practices: we launched multiple anonymous surveys to hear feedback from all our members, we held a listening session to promote group discussions of issues, we brainstormed ways to broaden our geographic reach, we instituted a new DEI committee, and we looked for ways to offset the carbon footprint associated with air travel to our conferences. We also have taken steps to create more space on the program for the annual meeting to talk about a broader range of topics. For instance, in recent years, the SBE opening plenaries at the annual meeting have focused on gender equality and intersectionality as well as philosophical approaches to race and business ethics.

Importantly, the SBE does not operate in a vacuum and is dependent on a heterogeneous population of doctoral students and faculty. In that regard, our universities need to do a better job of actively avoiding reliance on our social networks, which could prevent people of different backgrounds from entering doctoral programs, receiving academic positions, and obtaining tenure. Women are roughly half the population yet compose only a small fraction of tenured faculty at most universities. For the first eight years of my career, I was the only tenure-track woman in my department. In my doctoral program, male-only cohorts of five students were accepted by the department for several years in a row. Both academic institutions have improved their practices, but opportunities for progress still exist. We cannot expect our professional organizations to change if academia does not change, and we must realize our ability to stimulate change within our organizations.

Within business schools, we can stimulate change by providing normative analyses that other departments are not equipped to give. Our field could help businesses and universities navigate this balance between woke and woke washing by examining the normative basis for our policies and practices. For example, what are the boundaries for DEI education in business schools or employee training? Should Alt-Right values receive a spot on the syllabus? Recent scholarship may help us navigate these conversations with our communities (see Fremeaux, Reference Fremeaux2020). Just as a firm that possesses a scarce necessity helps by contributing a patented vaccine, so should business ethicists be expected to have an eye on our community’s needs.

In short, we can revisit the previous critique of CSIs, replace the language of CSIs with the language of business ethics, and see how claims of inconsistency could be aimed at the field of business ethics from both groups of critics. For example, the “woke” critics may say that the content of our courses does not reflect the broader spectrum of capitalist values and beliefs in the business community or, worse, does not belong in business schools. The “woke washing” group may argue that the field’s own practices lack consistency and do not align with the objectives and values that it espouses for business organizations. Both groups of critics would possess a shared focus on inconsistencies.

Up to this point, I have laid out some potential criticisms for our field’s inconsistencies that mirror those experienced by firms for CSIs, but I have not addressed whether such inconsistencies are morally problematic. This will be the focus of the remainder of the article.

ARE INCONSISTENCIES MORALLY PROBLEMATIC?

Firms are being labeled as woke or woke washed for their CSIs that are deemed to involve some perceived inconsistencies, and I assert that these labels tarnish the image of the firms with their respective audiences. This discussion, until now, has focused on the descriptive aspects of the stigmatization process but has not addressed the morality of CSIs that are regarded as inconsistent with some aspects of the firms (purposes, values, practices).

In this section, I present several approaches to considering the morality of inconsistencies, especially of those noted by critics of COVID-19 and BLM CSIs. Throughout the discussion, I note the implications for our own field, because, as I have suggested, we could be next in line for accusations of woke or woke washing based on our inconsistencies. I do not, however, address the morality of CSIs, which has been effectively analyzed in previous research (Dunfee, Reference Dunfee2006; Hsieh, Reference Hsieh2004; Margolis & Walsh, Reference Margolis and Walsh2003).

Not Morally Problematic

For normative theories that support the ethical evaluation of inconsistencies and CSIs, we could turn to utilitarianism, virtue ethics, Kantian ethics, and social contract theory. Utilitarians may not find inconsistencies morally problematic if the CSI produces the greatest good for the greatest number (Mill, Reference Mill1861). The virtue ethicists may not find inconsistencies to be morally problematic if we assume that corporations possess character and that the CSI reflects good character (Moore, Reference Moore2005; Solomon, Reference Solomon1992). A social contract theorist would not find inconsistencies morally problematic if a community does not expect consistency between CSIs and a firm’s values, practices, or purpose (Donaldson & Dunfee, Reference Donaldson and Dunfee1994).

Kantian ethicists may not find inconsistencies associated with CSIs to be morally problematic, so long as the CSI demonstrates respect for persons (Arnold & Bowie, Reference Arnold and Bowie2003; Bowie, Reference Bowie2017), can be present simultaneously in all similar businesses (i.e., is not self-refuting when universalized) (Bowie, Reference Bowie2017; Korsgaard, Reference Korsgaard1996; Scharding, Reference Scharding2015), or could not reasonably be rejected by any affected parties (Scanlon, Reference Scanlon1998; Scharding & Warren, Reference Scharding and Warrenin press). If we conceptualize the COVID-19 CSIs and criticisms for Alphabet in the form of Kantian maxims (Korsgaard, Reference Korsgaard1996), we may arrive at the following: “Alphabet does not monitor YouTube postings to maintain profitability” and “Alphabet provides information about COVID-19 and vaccines to help mitigate the pandemic.” The maxims appear to conflict with each other (helping to mitigate that the pandemic reduces profitability), but they seem internally acceptable. Though Alphabet’s lack of monitoring limits the efficacy of its COVID-19 mitigation initiatives, this maxim is not self-refuting when applied universally to website platforms (i.e., it is possible for all website platforms to maintain profitability by not monitoring postings as a universal rule, while simultaneously mitigating the pandemic by providing information about COVID-19 and vaccines). A broader maxim that attempts to incorporate both could be constructed, such as “Alphabet does not monitor YouTube postings, some of which contain misinformation about COVID-19, while otherwise working to mitigate COVID-19.” Alphabet’s lack of monitoring limits the efficacy of its COVID-19 mitigation initiatives, a concern that could be relevant from a utilitarian perspective, but this maxim also demonstrates respect for persons and is not self-refuting when universalized, which is what matters from a Kantian perspective. All website platforms could engage in some efforts to mitigate COVID-19 while failing to mitigate COVID-19 in a maximally efficient way.

Moral perfectionism is another way to think about the moral implications of inconsistencies. Moral perfectionism involves the pursuit of moral objectives, such as a good life, and an expectation that an individual will strive to achieve consistency between the individual’s actions and objectives (Wall, Reference Wall2021). Actions that are inconsistent with the moral objectives are considered morally problematic. Moral purism is a related concept yet requires that not only the behavior but also the intentions behind the behavior align with a moral objective (Dubbink & van Liedekerke, Reference Dubbink and van Liedekerke2020; Scharding, Eastman, Ciulla, & Warren, Reference Scharding, Eastman, Ciulla and Warrenin press). If a firm’s CSI stems from not only a desire to improve social welfare but also some self-interest (e.g., profit motives), then it is not moral. As Dubbink and van Liedekerke (Reference Dubbink and van Liedekerke2020) indicate, few actions meet the strict criteria of moral purism.

To some extent, both woke and woke-washing critics fail to articulate the moral objective that they are using when judging a firm for being inconsistent. As mentioned earlier, the “woke” critic seems focused on financial profits and shareholder capitalism, while the “woke washing” critic is focused on conflicting business practices. Misalignment or inconsistencies cannot be morally problematic if a moral objective has not been offered or targeted. Because neither set of critics pinpoints a moral objective, it is difficult to declare the inconsistencies associated with CSIs to be morally problematic from a moral purism or perfection perspective. For example, I may be inconsistent with my preferred color choices (e.g., some days I prefer blue, whereas some days I prefer orange), but I have not demonstrated moral imperfection because no moral objective was used to assess my behavior.

In the language of the business ethics field, these normative analyses suggest that we can examine a business case or a specific practice within our organizations and deem them morally acceptable even if they are inconsistent with the organizations’ practices, purposes, or values. This means that if I discuss a case on Merck’s development and donation of a drug to treat river blindness, I do not need to research all of the firm’s activities outside the details of the case and confirm consistency with all other firm activities. Similarly, excluding some sets of values or conceptions of justice that appear in the broader business community from a business ethics course is not morally problematic.

In short, many normative theories suggest it may not be morally problematic if CSIs are inconsistent with firm practices, values, or purposes. It is also morally acceptable for the business ethics field to possess inconsistencies in their pedagogy and organizations. Still, other perspectives suggest that inconsistencies are morally problematic.

Morally Problematic

The same normative theories that were used to suggest that inconsistencies associated with CSIs are not morally problematic could be used to suggest that these inconsistencies are morally problematic. Utilitarians may find inconsistency morally problematic if the CSIs do not produce the greatest good for the greatest number (Mill, Reference Mill1861). Virtue ethicists who believe in the existence of corporate character (Moore, Reference Moore2005) may find inconsistencies morally problematic if they lead to the development of bad character traits (Hartman, Reference Hartman1994). To the extent that a community believes that these CSIs should be judged as part of the whole organization and consistency is expected throughout the organization, these broader inconsistencies could be morally problematic from a social contract perspective, such as integrative social contract theory (Donaldson & Dunfee, Reference Donaldson and Dunfee1994).

Kantian ethicists may find inconsistencies associated with CSIs morally problematic when they cannot be universalized or would undermine the firm’s continued viability if they were. Bowie (Reference Bowie2017) discussed the role of pragmatic contradictions, which occur when a principle that promotes a behavior would defeat the purpose of the firm if the principle were universally adopted. Arnold and Bowie (Reference Arnold and Bowie2003) give the example of a firm adopting a principle related to the violation of law which, if universally adopted, would prevent firms from operating, as firms require the recognition of laws to conduct business. In terms of CSIs, a pharmaceutical company that adopts a CSI that entails the donation of faulty, expired drugs to a population in need would, if universalized, undermine trust and thereby make it impossible for the company to fulfill its purpose as a trusted seller of drugs.

Moral purists will find inconsistencies problematic for the reasons reviewed in the last section. As mentioned earlier, the moral objective needs to be identified, and often the critics do not articulate one. If the moral objective is assumed to be social welfare and a CSI is adopted with self-interested intentions (e.g., profit motives), then it would violate moral purism. For example, if Alphabet posts COVID-19 vaccine information on YouTube but does so to increase profits or deflect bad press, then the moral purist would not deem this action worthy of moral praise, no matter how much the action benefits society.

Moral perfectionism offers similar analyses. Steps could be taken to connect the financial welfare of the firm to a moral objective (see Scharding et al., Reference Scharding, Eastman, Ciulla and Warrenin press). If communicating COVID-19 vaccine information is not central to the firm’s financial performance, then the “woke” critic may argue that the CSI is inconsistent and therefore immoral relative to the firm’s purpose. By evoking obligations of stakeholder primacy, critics could argue that Alphabet’s CSI is morally problematic because it wastes shareholder investment on COVID-19 vaccine information.

If you deem firm inconsistencies to be morally problematic, then that raises a whole set of follow-up questions: Should organizations be advised only to adopt a CSI or respond to a social issue when they are certain their firms’ operations are perfectly aligned with the initiative? Should organizations stay silent when they have not reached consistency between their practices, values, and purpose?

If inconsistencies are morally problematic, then we, as a field, should be examining our own inconsistencies in our teaching and in our organizations. From a teaching perspective, that means that we should not judge the ethical nature of the CSI unless we take the steps to determine how the firm’s initiative aligns with the rest of the firm’s operations, values, and purpose. This requires more extensive research of cases. We also need to integrate more values and conceptions of justice into our courses. Furthermore, our professional and academic organizations should not espouse objectives or ideals until the organization’s practices are in full alignment.

In short, the moral assessment of inconsistencies can vary based upon the normative perspective as well as the details of the company and the CSI. Regardless, I will argue that business ethicists have a role to play in the stigmatization of CSIs as well as the potential criticism that the field may experience.

FINAL THOUGHTS AND FUTURE STEPS

Both woke and woke washing critics are using labels to create stigmas that they hope will punish targeted firms through divestments, boycotts, or legislation when they engage in social issues. These critics are acting like regulators in Dunfee’s (Reference Dunfee1998) marketplace of morality by trying to stop firms from extracting value from actions or policies that they do not deem to be moral. At the same time, citizens are demanding action from businesses, even if these actions could expose businesses to criticisms (Edelman, 2021). According to survey data collected in Fall 2020, 66 percent of more than thirty-three thousand global respondents from twenty-eight countries agreed that “CEOs should take the lead on change rather than waiting for government to impose it” (Edelman, 2021). In this survey, respondents also rated academic experts as the most credible source of information about a company (Edelman, 2021). Thus citizens want firms to act on social issues and critics punish firms for doing so. Perhaps business ethicists could serve as auditors in the marketplace of morality by discerning what is a moral violation and on what grounds. This is our moment, and we, as a field, could be more vocal about the stigmatization of CSIs. Some may say that our silence is warranted because we are plagued by many of these same inconsistencies. Yet I argue that we possess the skills to provide normative analyses, and according to this survey research, the public trusts academics as a source of information. If we believe that certain inconsistencies are morally problematic, we should speak up, and if we do not, then we should share our thoughts too. By doing so, we can be an impetus for change.

In this section, I consider three contested areas that align with the research expertise of our community: competing conceptualizations of a firm’s purpose, the value of hypocrisy, and the role of intentions.

Firm Purpose and Ethical Customs

It is possible that the battle between woke and woke-washing critics lies in the conceptualizations of a firm’s purpose and cannot be easily reconciled or simultaneously satisfied. The woke perspective may rest upon a conception of the firm’s objective that best aligns with shareholder primacy (Friedman, Reference Friedman1970), while those who use the language of woke washing may endorse stakeholder primacy (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984). Yet, even Friedman’s theory of shareholder primacy leaves room for CSIs that fall within “ethical customs.” For example, Friedman claimed that even the socially-oriented practices of Whole Foods aligned with his ideology (Friedman, Mackey, & Rodgers, Reference Friedman, Mackey and Rodgers2005). It is possible that the recent difference in the critics’ perspectives of CSIs reflect a shift regarding Friedman’s “ethical customs” such that certain CSIs related to green operations (e.g., basic recycling) have become well-accepted, legitimate practices, but social justice initiatives are still contested activities that do not clearly (or unanimously) fall within the ethical customs. Abela (Reference Abela2020) is willing to grant that some of the social justice activities may be part of ethical customs but notes that “Friedman didn’t address what to do when ‘ethical custom’ is inimical to free enterprise itself.”

If shareholder primacy lies at the heart of this conflict and shareholders’ rights are being violated, then the shareholders should be protesting. Instead, we see recent evidence of the opposite trend. For example, corporations that publicly stated support for BLM are now experiencing pressure from shareholder activists to provide more meaningful reporting on DEI within their organizations, and in recent months, many shareholders have voted to adopt more detailed DEI reporting on firms’ demographics (Sumagaysay, Reference Sumagaysay2021).

More generally, the financial benefits of CSR practices are not fully understood, so it is difficult to make definitive claims that CSIs violate shareholder primacy. For instance, a recent article by Barnett, Hartmann, and Salomon (Reference Barnett, Hartmann and Salomon2018) reveals that firms with more CSR activities are less likely to be sued. This is possibly one reason why Friedman did not regard Whole Foods’ activities regarding social issues to be antithetical to shareholder primacy (Friedman, Mackey, & Rodgers, Reference Friedman, Mackey and Rodgers2005).

Though the merits of stakeholder primacy versus stockholder primacy have been deeply considered by experts in our academic community, our voices could advance the debate that is playing out between critics claiming that CSIs are woke or woke washing.

Hypocrisy and Reflection

We should embrace conflicting perspectives and look for ways to make progress within the two groups of critics. Cho and colleagues (Reference Cho, Laine, Roberts and Rodrigue2015: 84) explain, “Hypocrisy can manufacture opportunities for change that are much less likely to arise without it, and it can help sustain the societal legitimacy of organizations that deal with significant conflict among stakeholders.” For example, donation programs (buy one, give one) have been criticized for affecting local economies (Jost, Reference Jost2016). TOMS, a purpose-driven firm with a business model that centered on the donation of a shoe to a child in need for every shoe purchased, recently changed its business model owing to criticisms from activists. The activists noted that while TOMS was helping the children obtain shoes, it was harming the African businesses that produce shoes and, more broadly, local economic development (London, Reference London2014). After listening to this criticism, TOMS shifted where it manufactured its shoes to the local economies that it hoped to help and moved from a shoe donation program toward financial donations (Digital Marketing Institute, 2021). Here we see how claims of hypocrisy motivated change.

While claims of hypocrisy should cause us to pause and reflect, we also must realize that such claims do not automatically indicate that a moral violation has occurred. As mentioned previously, I believe our ability to provide normative analyses is where we can add value to current debates regarding woke and woke-washing CSIs. In my forthcoming article with Tobey Scharding, we introduce the intersubjective reflection process (IR process) to guide normative evaluations of workplace practices, especially those that arise in contested domains (i.e., when attitudinal and behavioral norms conflict or are not well formed). The IR process is grounded in Scanlonian contractualism and asks decision makers to consider if any affected party to a workplace practice would reject the practice for intersubjectively valid reasons (i.e., reasons that are grounded in normative standards and could be understood by all). I believe that the IR process is helpful for assessing CSIs and initiatives of the SBE because it draws attention away from simple, subjective reasons for rejecting a practice and requires consideration of perspectives of all other affected parties, not just those who have traditionally been privileged with decision-making capacities. It forces us to imagine the perspectives of others and what would give them a reasonable reason to reject a particular practice using a normative standard. If we connect the IR process back to the adoption of CSIs, we would consider the intersubjectively valid reasons for rejecting the CSI from the vantage point of those who could refer to the initiative as woke washing as well as those who might claim that the initiative is woke. Using the IR process would help decision makers distinguish when woke washing is a normatively significant criticism from when it reflects the critic’s subjective biases. Similarly, if the allegedly woke group cannot provide an intersubjectively valid reason to reject the initiative (i.e., one that is based on a normative standard and can be understood by the other parties), then the firm may proceed with the CSI. Likewise, if our teaching of cases without a full grasp of inconsistencies between a firm’s purpose, values, and current practices cannot be rejected by any of the affected parties for intersubjectively valid reasons, then we, too, can proceed with teaching our cases.

Firm Motivation

While the woke and woke washing critics may infer corporate intent regarding a particular CSI, in practice, it is quite difficult to detect. As noted earlier, firms can use CSIs to stave off stigma (Grougiou et al., Reference Grougiou, Dedoulis and Leventis2016). Others may adopt well-meaning initiatives that fail, such as Starbucks’ “Race Together” initiative (Sabadoz & Singer, Reference Sabadoz and Singer2017). Recently, Sigel (Reference Sigel2021) considered the possibility of shareholder lawsuits in response to CSR statements and goals such that directors could be sued for failing to follow through on bad faith CSR efforts. She, however, notes the difficulty in clearly defining good faith and bad faith. More generally, it is difficult to detect an individual’s true intent when engaging in charitable activities, whether it be altruistic or self-interested, so we should not expect to be able to detect a corporation’s intent behind every CSI. If we demand this level of knowledge regarding every CSI, we will have no CSIs.

Furthermore, I believe that those firms that adopt a CSI for self-serving reasons (to stay in line with competitors, to gain new customers, or to attract new shareholders) can still have a positive impact on the organization itself or on society. For example, imagine an organization adopts a program to appear interested in women’s rights and avoid criticisms from social activists (e.g., extended maternity leave). In doing so, it may inadvertently create a more equitable organization because a higher number of women return to work rather than quitting when they have a child. In this sense, the program can cause real change in the composition of the organization, regardless of the firm’s motivations.

Similarly, the use of the rainbow flag as a label for certain products may initially be motivated by a desire to attract customers, but even shallow signs of support provide legitimacy to gay rights and can shift public perceptions of acceptability. Furthermore, the use of symbols, even if superficial, exposes a firm to criticism, such as hypocrisy, that can stimulate real change as seen by the shareholder activists who demanded more DEI reporting. Conversely, firms may choose to take the opposite position. They may restrict benefits to same-sex partners or donate to charities with anti-LGBTQ positions—and they also may face strong market reactions (Del Valle, Reference Del Valle2019). These various firms’ practices, while conflicting, are useful signals for understanding the marketplace of morality (Dunfee, Reference Dunfee1998), and as the auditors, we could help discern the normative validity underlying the criticisms of both sides.

Limitations

My analysis possesses several shortcomings, which I address in this section. More specifically, I note my assumptions related to economic systems, politics, and inaction.

Capitalism

One limitation of my analysis is that it does not consider the structure of the economic system—it takes the current economic system for granted. Some may argue that the capitalist system is broken or ill suited to addressing social issues and gives rise to these CSIs. If we were to address issues with the economic system, we would not need firms voluntarily to address social issues. Just as I am calling for the consideration of systematic problems in business and teaching, perhaps I should be calling for the consideration of systemic problems within economic systems.

Politics

Others may say that firms simply must refrain from engaging in CSIs that have political overtones and that social labeling of CSIs only occurs when firms overreach their bounds as economic organizations. Yet, even with the COVID-19 CSIs, firms experienced criticisms for misalignment between their CSI actions and firm practices, and political perspectives were not easily tied to the issues. Furthermore, a growing body of research argues that businesses are political organizations and that it is impossible to separate political and social issues (see Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007). In recent years, we have seen court rulings that promote corporate expenditures related to political action committees, which expand corporate influence in political activities (Skaife & Werner, Reference Skaife and Werner2020). If a society is accepting of corporations that directly fund political action committees, then it seems that ties to political influence alone should not be a reason to reject CSIs. Perhaps a broader consideration of corporate involvement in politics is needed.

Inaction

In the sample of the Top 50 of the Fortune 500 firms, Berkshire Hathaway was notably missing CSIs for BLM and COVID-19. Though the firm received pressure for its resistance to diversity reporting (Gibson, Reference Gibson2021), I did not find other criticisms for its lack of CSIs, but further investigation is warranted. As Coinbase and Basecamp have demonstrated, some firms intentionally avoid CSIs with the hope of avoiding criticism yet may receive backlash too.

CONCLUSION

In this presidential address, I examined CSIs, which are voluntary corporate acts supporting social issues, that can be regarded as inconsistent with a firm’s espoused purpose, values, or practices and lead to labels of “woke” or “woke washing.” I argued that this labeling is stigmatizing and may cause boycotts, divestment, and loss of employees. I warned that a parallel process could play out in our academic field and noted several areas of inconsistency between the practices of our field and our espoused purpose and values. Just like corporations, if we do not find the correct balance, we will be deemed too committed to a social issue (i.e., woke) or not committed enough (i.e., woke washing). I then considered the morality of inconsistencies and ended with a discussion of how our field could be more vocal in wading through the criticisms aimed at CSIs and, potentially, academia. My hope is that we do not become Basecamp or Coinbase and deem controversial issues outside the realm of acceptable discourse for an organization like ours.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on my presidential address delivered online to the Society for Business Ethics in July 2021. I expanded the content to address questions and comments posed during the presentation and provided by society members after the presentation. I appreciate the research assistance of Robin Hu and Jaclyn Didonato and guidance from the BEQ editors-in-chief. I am also grateful for the helpful guidance provided by Miguel Alzola, Oyku Arkan, Michael Barnett, Beth Bechky, Norm Bowie, Joanne Ciulla, Wayne Eastman, David Hess, Nien-he Hsieh, Lisa Lewin, Stefanie Remmer, Tobey Scharding, and Jason Stansbury, as well as the SBE members who made excellent points in the Zoom chat during my presidential address. All errors, of course, are my own.

Danielle E. Warren ([email protected]) is professor of management and global business at Rutgers Business School – Newark & New Brunswick. Her main contributions to scholarship lie in advancing our understanding of why deviance arises in business settings, how to evaluate it, and how to deter destructive deviance while promoting constructive deviance. She is a senior fellow of the Zicklin Center for Business Ethics Research at the Wharton School, a research fellow of the Rutgers Institute for Ethical Leadership, and a faculty fellow of the Rutgers Institute for Corporate Social Initiative. She received her MA and PhD from the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, and BS from Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey.