Migration, and its cultural and economic impact on societies and labour markets, is currently one of the most hotly debated topics in social and economic history, but theorizing its impact on both leaving and receiving societies still has far to go. Notwithstanding the huge literature on the negative and positive aspects of human movements, from assimilation to diaspora studies, most approaches are limited to specific historical or contemporary cases. Scholars who venture beyond description and whose aims are more ambitious have developed very interesting ideas, but the reach of their theories is also limited, as most are restricted to the modern period and the Western world. This holds as much for models that focus on the migration process itselfFootnote 2 as for studies primarily engaged in the ensuing settlement process.Footnote 3 The lack of theory at a more general level is understandable because migration and mobility depend largely on the specific historical and institutional context.Footnote 4

However, insights at a more abstract and general level are useful if we want to understand human developments over time, and more specifically the role of migrants as workers, both forced and free. Patrick Manning’s typology of migrations in the past 60,000 years and his hypothesis on the impact of cross-community migrations is a case in point. Our cross-cultural migration rate (CCMR) approach is indebted to Manning’s ideas and is meant to develop these further. For practical reasons, such as the availability of sources, we chose to apply them to a much more limited historical and geographical scope, starting with Eurasia since 1500. This operationalization is possible only if we have a clear qualitative and quantitative definition that enables researchers to measure the same phenomenon through time and space and thus make systematic comparisons possible.

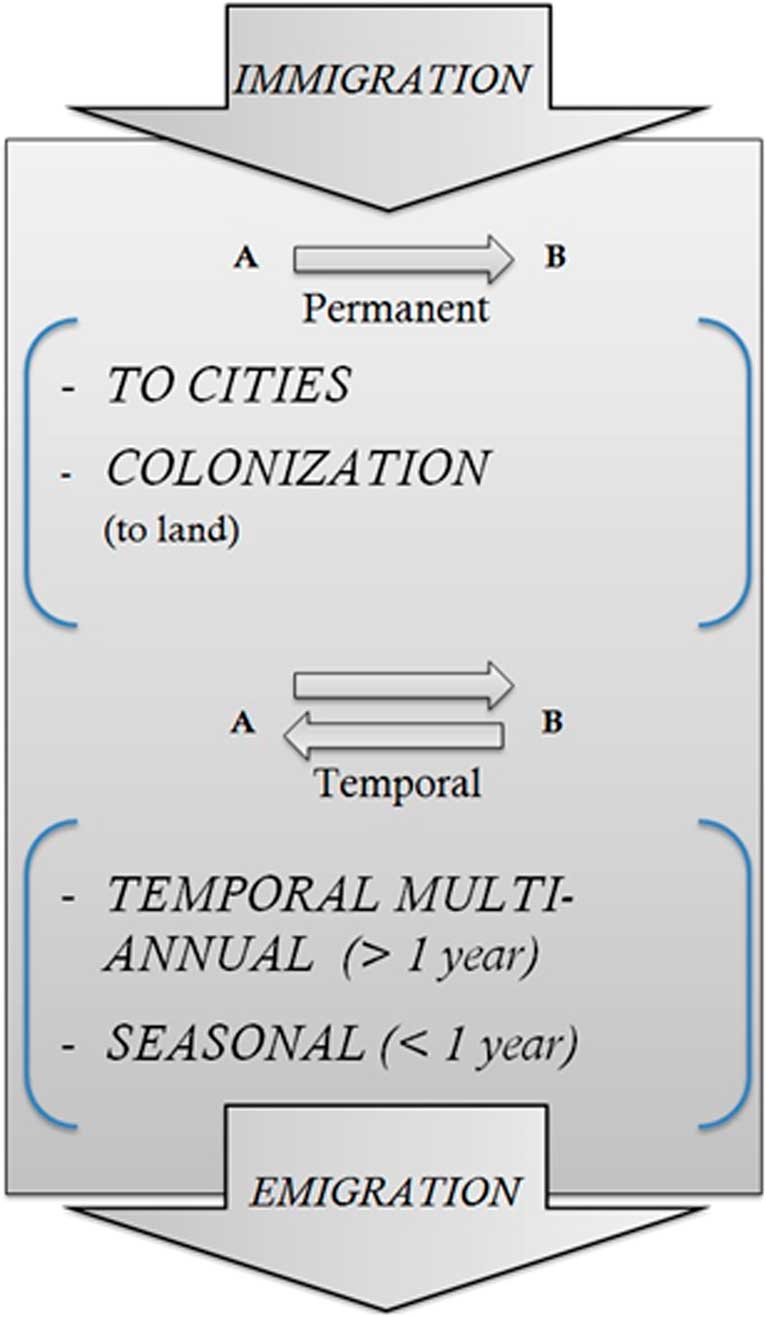

This does not mean that the CCMR approach is the best or the only one. It is simply the first attempt to come up with a unified method in a field characterized by the lack of a clear definition. As far as scholars share a more or less common definition (i.e. migration defined as international moves aimed at long-term settlement), this does not lend itself to an understanding of the impact of migration in a period that predates the nation state and ignores huge migrations within states and empires, as well as temporary and circular moves. The CCMR typology (Figure 1) combines both permanent and temporary migrations and, moreover, is a good starting point to link the four key types to different forms of labour relations.

Figure 1 The cross-cultural migration typology.

Like Manning’s, our formal definition encompasses people who cross a cultural boundary, linguistic or otherwise, and stay long enough for interactions with those they join to develop and hence possibly lead to social changes, negative or positive. From this, we assume that variations in cross-cultural migration rates can help explain differences in human development, and more specifically economic growth. This should not be read as a Whiggish, upbeat evolutionary position however. Invading migrants, such as Europeans in the New World, forged dramatic innovations (and economic growth), yet at the expense of those who inhabited these areas. Conversely, immigrants may be allocated a subservient position, characterized by structural discrimination, with African slaves in the Americas as the most telling example. Power asymmetries and people’s subjective perceptions therefore are always part of the larger picture. Nevertheless, migrations that resulted from coercion and ended in domination also changed people and societies, and it is these social and cultural changes that the CCMR approach tries to capture in order to enable explanations by way of systematic comparison.

Our main assumption is that the interactions between people with different cultural backgrounds, which, in general, are more reciprocal and peaceful than the extreme examples mentioned above, often lead to new ideas and qualitative modifications of human capital. This, in turn, changes not only the migrants, but also the people they have joined and those left behind and to whom they might return and with whom they might remain in contact. Migrants can spread new ideas and habits; by doing so, in interaction with others, innovation and social change are more likely than in areas with low CCMRs. The nature and extent of change depend, of course, on the characteristics of the migrants and the scope (institutional or otherwise) for interaction with the people they encounter. This means that these variables have to be factored in when we want to develop the CCMR approach further.Footnote 5 Our volume Globalising Migration History, published in 2014, and the subject of the present discussion dossier, is a first attempt to apply the CCMR approach to Europe and large tracts of Asia, especially the large empires, including Russia, China, and Japan, for the past four to five centuries.

DEFINITION

The most critical remarks on our CCMR approach come from Leo Douw, a specialist on the history of China. He argues that we are interested primarily in processes of assimilation in the sense of productive interaction as the long-term result of migrations, but that we fail to include “settlement” as one of our core categories. We certainly are interested in the longue durée, and, as we explained at the beginning of this rejoinder, what fascinates us most is the relationship between cross-cultural migration, both temporary and permanent, and sociocultural change. To assess such changes, settlement is, clearly, a key process and therefore part of our typology and embodied in both people moving to cities (urbanization) and in people moving to land (colonization), although some of them – especially those heading for cities – stayed only temporarily, as Lynn Lees rightly notes. Douw also asserts that we do not care about culture, because we fail to acknowledge the crucial difference between soldiers (as the most important representatives of our Temporary Multi-Annual – TMA – category) and settlers. We must stress, however, that the CCMR method states that cultural change depends both on temporary migrations and on long-term settlement, whether or not resulting in assimilation or minority formation or even extinction. Moreover, many recent studies amply show how soldiers who are sent to foreign lands can have a significant impact on the people they fight against or protect, but also change themselves in the process. A telling example are African-American soldiers stationed at German military bases during the Cold War and who were exposed to a less racialized and non-segregated society, which politicized many of them upon their return.Footnote 6

The interesting role of skilled migrants, many of whom are subsumed within the TMA category, is brought up in a different context by Manning, who stresses the importance of diasporic migrations on social change. This is an interesting point, as diasporic networks have multidirectional influences, both on the place where they settle and on the communities they have left but remain in contact with. The fact that we did not make “diaspora migration” a separate category does not mean we are blind to its cross-cultural impact. Many studies, such as Enseng Ho’s excellent The Graves of Tarim (2006), on Hadrami Yemeni who live across the Indian Ocean, show the power of such a diasporic transcultural approach.Footnote 7 To capture the concrete social changes brought about by cross-cultural migrations we therefore need a research agenda that furthers studies on encounters and interactions in concrete historical situations, to start with in cities. Urban historians, working within a CCMR framework, are well equipped to take the lead and thus refine – or even refute – our initial hypotheses.

This is not to say that the way we defined cultural boundaries is beyond discussion. We fully realize that our approach is rough, capturing only some broad boundaries. Furthermore, we are aware that, over time, the significance of the cultural difference may shift and diminish, as rightly remarked by Lynn Lees with respect to the transition from rural to urban environments, especially in the twentieth century. In the conclusion to our volume, we explicitly discuss this and make alternative calculations without including city-ward migration within regions or states that became culturally rather homogenous due to the nation state formation. Moreover, the CCMR approach offers researchers the choice of whether or not to include certain migrations, depending on the historical context. This leaves open the possibility to choose other cultural boundaries for migrants to cross, but, so far, we have not encountered alternatives that capture what CCM seeks or that lend themselves to systematic quantification.

Finally, the CCMR method says nothing about the direction and nature of cultural change. Depending on the prevailing power relations migrants, especially of the colonizing (land-to-land) type, might impose their culture on those already present, as in the case of the Sinification of frontier areas discussed in the chapter by Yuki Umeno on Manchuria.Footnote 8

THE FORMULA REVISITED

Our most important methodological claim is that explicitly defining cross-cultural migration rates enables explanations by way of systematic comparisons. This is not to say that our definitions and their combination in a formula are adequate, let alone the best possible. All participants in this debate have contributed, but Patrick Manning has made the most extensive attempt not only to demonstrate the flaws in our approach, but also to come up with improvements. Here, we will try to discuss them and to suggest practical applications. No less than seven possible improvements have been proposed:

1. Differentiating our categories “emigration” and “immigration” from and into the specific geographical unit of analysis chosen (a “territory”) according to the same subcategories we use inside this unit. Thinking through the concepts and definitions opted for, we would like to emphasize that the terms immigration and emigration should be explained in terms of culture. For a clear and mathematically strict definition, immigrants are then defined as “persons from a different cultural area that migrated into the chosen area at least once”. Possible remigration, etc., is interesting for several reasons, but not for the defined likelihood of a person migrating. The same goes for emigrants, who are defined as “persons from the chosen cultural area that migrated out”, again irrespective of their possible remigrations. Note that this definition excludes the possibility in our formula that an immigrant can be an emigrant at the same time, simply because of their different (by definition) cultural background. This prevents overcounting.

2. An extension of the units of analysis, in our case migrants, i.e. individuals, experiencing at least one cross-cultural migration in their life (p. 14), to migrations, i.e. the number of times that such migrations have taken place. Manning argues that “one might wish to give recognition to the experience of those who migrated multiple times in their life”. This, of course, makes perfect sense, but we have refrained, so far, from extending our formula to incorporate this frequency factor for two reasons. The first is that, most likely, the first migration experience (frequency 1) has the highest impact on the migrant and their way of thinking. However, we realize that this does not apply to those they meet in the new environment, which applies equally to different people encountered by the migrant during their first and further encounters, and ceteris paribus to those left behind who receive information from those among them who have emigrated but at the same time stayed in contact. The second reason is practical and has to do with the difficulty of finding enough historical evidence. That said, where such information is available in two or more cases to be compared, such an extension of our definition may yield important results.

3. As a unit of analysis, Manning remarks, we might also choose the number of years spent by an individual as a migrant. Here, the same remarks apply as those formulated under 2.

4. The measurement of emigration out of the geographical unit of analysis and immigration into that same unit is a related issue. Because our starting point is the first migration experience of individuals, we must avoid double counting in the case of persons who both emigrate and return to that unit; in other words, of emigrants who, at a later stage within the time unit of analysis, become immigrants by “remigration”, or vice versa. For all kinds of questions, it may be important not to avoid such double countings, and, in such cases, the frequency has to be included (as discussed under 2), or differentiating the categories “emigration” and “immigration” (as discussed under 1) might provide an adequate solution.

5. Differentiating the individuals studied into women and men. This would be a valuable improvement and will be discussed below in a separate section. Mathematically, this can easily be handled using the existing formula: only the migrants of a certain gender are counted. The average population is now just the average population of the specific gender. Lastly, the average lifetime is the average lifetime of persons of that gender. The outcome is the probability that a person of this gender migrates during his/her lifetime. Note that the average for men and women is not necessarily the same as the overall likelihood of migration, since the number of men and women are not necessarily equal.

6. The time unit chosen, both its length and its starting point, is not determined by our definition. The formula already allows for shorter or longer periods. Ignoring the second term of the formula in our original examples might have complicated our explanation of the formula. We would very much applaud research that uses different time units, but we realize that this requires much more detailed historical data than we have provided so far.

Note that the formula does not even require periods to be equal in length. For long-term comparisons, the initial period used might even comprise 1,000 years, whereas in more recent times this can be reduced to decades. Or, from a more practical perspective, one can simply consider just the periods for which data is available.

7. The definition of the denominator in the CCMR can be improved, as Manning convincingly argues. He claims it would be much more precise to “try to count the number of migrants [in a particular geographical unit] in the period as a percentage of the number of persons who ever lived in that period” instead of the population at the midpoint of the period chosen.

Taking this literally, older persons at the beginning of the period are counted fully, as well as young children at the end of the period. This introduces a mathematical inconsequence in relation to the numerator. However, the idea of developing a more sophisticated measure is clearly useful. We believe that the correct quantity to take into account here is simply the average population living in a certain area during a certain period. Note that for shorter periods the population at the midpoint of the period is still, in most cases, a very good approximation.

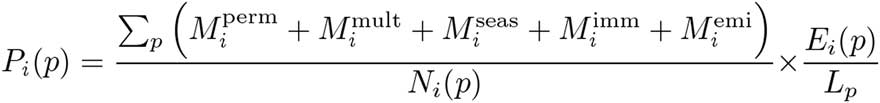

The various improvements imply the following reformulation of the terms in our original formula:

Figure 2 Note: P i (p) denotes the probability of a person living in period p and geographical unit i migrating in a lifetime. M i perm, M i mult, and M i seas denote permanent (to cities and to rural areas), multi-annual (labour migration) and seasonal cross-cultural, often long-distance, movements inside unit i, respectively. M i imm is the number of immigrants Footnote 29 to unit i from outside and M i emi the number of emigrants* from unit i to elsewhere. The notation Σ p indicates that these migration numbers are summed over period p. N i (p) is the average population in geographical unit i in period p. To compensate for overcounting in the migration numbers, the expression needs to be corrected by the second factor, in which E i (p) denotes the average life expectancy in period p and L p is the length of the period.

We certainly do not wish to give the impression that these reformulated definitions mark the end of the discussion. Any future suggestions are more than welcome. However, we do believe that the above definitions are already clearer and more intuitive than before, and that the formula is robust.

METHOD

The outcomes of the CCMR approach depend on the scale of analysis and the available sources. Lynn Lees is right to point out that there is some irony in the fact that while we want to steer away from the nation state, at the same time our approach to a large extent privileges states and empires as units of analysis, not in the least because these types of polities have produced a lot of migration data, even before the rise of the nation state in the nineteenth century. Although the method can as such equally target regional or – at the other end of the continuum – continental levels,Footnote 9 Lees is right in observing that in most chapters the level of analysis is rather macro, which leads to the dominance of state regimes to the detriment of individuals, households, and their repertoires. Although micro and meso levels are central in the chapters on Indian weavers (Ramaswamy), Han Chinese settlers (Umeno), and Lisu migration (Mazard), due to the focus on states and empires our volume targets principally the macro and in particular national levels.Footnote 10 But, again, this was a deliberate choice at this point of our long-term project, as we were eager to first outline the big picture; it was certainly not the inevitable result of the CCMR approach as such.

Another problem is the critique formulated by Lynn Lees, as well as Leslie Page Moch, on the negligence of marginal migrants, at least from the perspective of the state. As James Scott has argued in his two most recent monographs,Footnote 11 states to a large extent decide what parts of the population are made “legible” and are quite myopic when it comes to marginal groups that try to escape its gaze, such as the semi-nomadic Lisu, described in Mireille Mazard’s chapter in our volume, as well as the sea-born communities analysed in Atsushi Ota’s contribution.Footnote 12 But that critique might also extend to those internal migrants, such as tramping artisans and domestics, who often do not show up on the state’s radar. We share the concerns of Lees and Moch, and have factored the most numerous groups into our calculations, albeit on the basis of guestimates, due to the lack of systematic sources.Footnote 13

In the same vein, Lynn Lees and Leslie Page Moch discuss the disproportionally important role of relatively small numbers of merchants, specialists, or religious networks in forging social change and innovation; these are invisible at the macro level and insignificant in quantitative terms. Although most chapters in Globalising Migration History adopt the aggregated macro level and thus ignore the impact of relatively small “organizational” migrants,Footnote 14 like the “Twenty-Five Thousanders” in the Soviet Union analysed by Lewis Siegelbaum and Leslie Page Moch,Footnote 15 this disregard is not the consequence of the CCMR approach as such, but follows from the level of analysis. It does, though, raise the issue of the differential impact of the four core modes of migration that we have distinguished in our model, to which we will return in the section on the Great Divergence.

GENDER

Several commentators have pointed to the neglect of gender in our volume, and rightly so. Again, this is more the consequence of opting for the macro level than a fundamental flaw of the CCMR approach. Nevertheless, in the source materials on which the volume is based gender is often distinguished, and we aim to make this differentiation systematic in the near future. As soon as we descend to the meso or micro level, gender immediately becomes visible and highly relevant. Firstly, because within households gender patterns determine whether and what female members are expected to leave, temporarily or more definitively (for example through marriage). As we have argued elsewhere, family systems are key in this respect, because they embody the prevailing gender norms and rules, which vary hugely from region to region.Footnote 16 It is, therefore, important to study more in depth the different roles of male and female migrants, and their interaction in the societies they join. Lynn Lees adds that cultural boundaries exist within rural areas, too, and that women crossed those boundaries through exogamous marriage. This is undoubtedly true, and widely studied in the field of historical demography. It would be interesting to develop ideas as to where such boundaries run and to assess their salience.

THE GREAT DIVERGENCE DEBATE

In the conclusion to our volume, we tried to link the results of our CCMR approach to the Great Divergence debate, sparked by Ken Pomeranz’s seminal eponymous book. We argued that the fact that CCMRs developed differently in Europe and East Asia is consistent with the diverging and, more recently, converging economic developments in these two parts of the world, with China and Japan following distinct paths. This brings us to the point that Leo Douw implicitly raises in his contribution to this dossier, which is whether we should attach weights to the four different core types of cross-cultural migration. We argued that there are good reasons to assume that rural-urban migrations are more transformative than rural-rural (colonization) migrations. The reasons being, principally, that cities have different (public) institutional settings than the countryside and provide a space of denser and culturally diverse interactions. Although they differ over time and between world regions, urban institutions generally offer more scope to develop individual skills and interact and bond or compete with people from different cultural backgrounds, thus providing a social network different from that of kin and family.

In other words, cross-cultural interactions following from migration to cities are more numerous, more intense, more varied, and more open than colonizing migrations, where migrants often move in family groups and interact in a much more limited way. Of course, these generalizations do not apply equally to each situation, and how open and horizontal migrants and natives can mix depends very much on the urban membership regime.Footnote 17 Bangladeshi labour migrants in Qatar, many of whom would be in the rural-to-urban category, have barely any chance to interact with natives, as they are highly segregated and excluded from urban, let alone national, citizenship, whereas, notwithstanding discrimination and stigmatization, legal – and partly even illegal – low-skilled immigrants in liberal democracies in time become full citizens. We fully realize though that this “full citizenship model”, which, in theory, offers open access to all legal migrants, can also lead to “black holes” that, in practice, severely limit the level playing field for immigrants and their descendants, who experience downward social mobility and minoritization, with the American hyperghettos and French banlieues as the best known examples of what Loïc Wacquant calls “advanced marginality”.Footnote 18

Moreover, in cities characterized by limited forms of “open access”, migrants may organize more along ethnic lines, as was the case in many Chinese cities well into the twentieth century, and especially so with merchants, who were organized in hometown associations (Huiguan) and thus institutionalized ethnic bonds,Footnote 19 which reduced the openness and intensity of the contact with other city dwellers. However, the fact that context matters does not alter the likelihood that, in general, migration to cities has a stronger transformative effect and thus weighs much more heavily than colonization. And, it is precisely rural-to-urban migrations that predominate in north-western Europe in the period 1500–1900, whereas in China colonization was much more important, with some twelve million people moving to frontiers between 1680 and 1850. The greatest divergence in migrations to cities occurred in the period 1750–1850, when European cities almost quadrupled in size and the urban graveyard effect disappeared. It seems no coincidence that it was only when the massive migration to Chinese cities from the late 1970s onwards (and in Japan a century earlier) took off that economic growth followed suit.

The importance of cities as high-pressure cookers links the CCMR approach to an even broader debate on the role of labour as a production factor in understanding economic growth. We believe our volume shows that there are good reasons to take migrant labour much more seriously. Instead of just assuming that labour is undifferentiated and will be available where and when needed, the field of human capital studies not only shows the importance of skills, but also their transportable and shareable nature.Footnote 20 And this is where migration comes in. By voting with their feet, workers transport their skills to another place and subsequently share their knowledge and experience with people from different cultural backgrounds. But migrants also improve their skills by moving to new places and institutions, such as cities, ships, armies, outposts, which they then might transport back to where they came from, or further, in the case of circular and return migrations. Depending on the context, such encounters often have positive economic outcomes, as has been shown extensively by economists for one of our key types of cross-cultural migration, people moving from the countryside to cities.Footnote 21 Recent work by Gareth Austin and Kaoru Sugihara on the East Asian labour-intensive industrialization added a new layer to this body of knowledge.Footnote 22 Inspired by Kuznets’ work from the 1950s and that of Akira Hayami a decade later, they stress the importance of the transferability of rural skills (planning, organizing, and time keeping, for example) – acquired through intensive rice cultivation or proto-industrial activities. And these skills explain the success of – small-scale – industrial enterprises in East Asia, as well as in some Western European regions. This reminds us that the countryside was highly differentiated, and this should also be taken into account when theorizing the CCMR approach further.

Finally, we take the opportunity to discuss an issue raised by Lynn Lees on the role of colonies in the head start of north-western Europe. Patterns of cross-cultural migration in this part of the world can be understood only in the larger context of empire, plantation economies, and colonies. As Adam McKeown in our volume rightly remarks, the comparison of an empire (China) with a continent (Europe) as unit of analysis makes the importance of the overseas expansion of European empires, especially in the Americas, invisible, reducing it largely to the category of “emigration” in our model.Footnote 23 Like the frontiers in the north and the west of the (land-)expanding Chinese empire, the Atlantic plantation complex could also be considered an integral part of the European economy and migration circuits. By including these, the share of colonization migration would rise somewhat, but, as Table 1 shows, apart from the first half of the seventeenth century, when almost a million Spanish and Portuguese migrants left for South America, the pre-1800 dominance of migrations to cities (in Western Europe) and to land (in China) remains.

Table 1 Number of colonizing migrants (000s) and (adjusted) colonization rates for Europe and China (1601–1800).

Sources: Jan Lucassen and Leo Lucassen, “The Mobility Transition in Europe Revisited, 1500–1900. Sources and Methods”, IISH Research Paper 46 (Amsterdam, 2010), and McKeown, “A Different Transition: Human Mobility in China, 1600–1900”, in Lucassen and Lucassen, Globalising Migration History.

As with determining the “weights”, discussed above, which depends on the specific historical context, this unpacking of the category “emigration” in the case of Europe in the early modern period and the resulting recalculations show the flexibility of the CCMR approach, as it offers scholars the possibility to choose their own levels of analysis, depending on their specific research questions.

MIGRATION AND GLOBAL LABOUR HISTORY

As argued elsewhere, labour history and migration history have many things in common, and by joining forces they mutually reinforce each other.Footnote 24 Workers are often migrants, and their geographical mobility matters if we want to understand individual patterns of social mobility, social movements, skill formation, and collective identities. Men and women who move to other places take their skills, norms, primary identities, and social repertoires with them. At the point of destination, this might lead to conflicts, discrimination, and exclusion, but also to the dissemination of new ideas and the forging of new solidarities.

A good example are the virulent anti-Italian protests and discourse of French workers and unions at the end of the nineteenth century, which led to an outright chasses à l’Italien costing the lives of dozens of migrant workers. Within decades, however, this extreme nativism had decreased considerably, as Italians joined French unions while adding their own flavour of syndicalism. Italian socialist union leaders, like Luigi Campolonghi, was even sent to France to organize his compatriots.Footnote 25 Such cross-cultural effects of migration are also well illustrated by the recent blossoming historiography on the transnational links of anarchists in Europe and the Americas.Footnote 26 Our CCM typology includes such encounters but casts the net much wider while at the same time offering new ideas on the relationship between the four key forms of cross-cultural migration and the mobility of labour and labour relations.

Whereas people who moved to cities hoped to earn money as wage workers in urban industries and services, or as self-employed artisans, those involved in colonization migration set up farms or became agricultural workers. The majority, however, were forced to work as slaves or indentured labourers on large-scale plantations both in the Americas and Asia. Seasonal migrants predominantly combined self-employment as peasants with temporary wage labour in commercialized agricultural regions or in cities, as domestics or construction workers. Labour migrants who stayed away longer than a year (TMA) with the intention of returning often joined institutions such as the army or navy, whereas a minority of higher-skilled workers ended up as bureaucrats or specialists working for the state, the church (missionaries), or for large, transnational, industrial and trading companies. Although there is overlap in the types of labour relation between the four main types of migration, there are also distinct combinations that help us understand better the development and shifts in labour relations forged by distinct cross-cultural migrations. Temporary work by Russian peasants and serfs in cities, for example, introduced them to the urban environment in which wages and commerce dominated. By functioning as a bridge between more or less autarkic and commercialized regions, these temporary migrants, in the long run, loosened the ties with the countryside and paved the way for large-scale industrial wage labour.Footnote 27

Although we do not claim that the CCMR perspective is the only or best way to further develop global migration and labour history in the future, we do believe that for systematic comparisons of migrations in different time periods and different world regions an agreed definition and typology is crucial, not only because it furthers our understanding of migration as a social process, but also because it enables migration and social historians to think more explicitly about the role of migration as an independent variable in all kinds of more general processes and long-term developments, be they cultural, political, social, or economic.Footnote 28