Marx discovered and history has confirmed that the capitalist and the worker are the principal opposed personages of our time, and the mercenary and the internationalist fighter embody the same irreconcilable opposition.

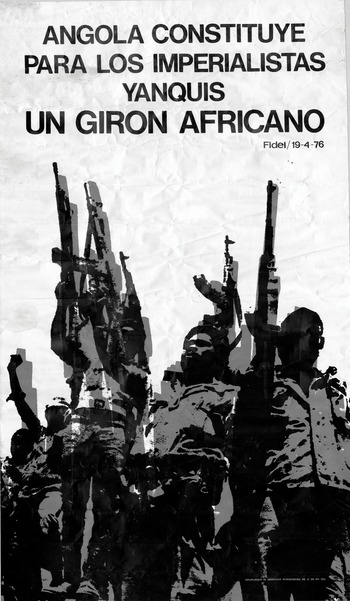

In some ways, the year 1976 represented the peak of Tricontinental solidarity. Cuban soldiers operating halfway around the world in the former Portuguese colony of Angola helped consolidate power for the leftist Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola, or MPLA) in the face of concerted opposition. They repelled a coalition of local nationalist parties, South African soldiers, and covert Western assistance that sought to deny the MPLA its claim to authority in the months after independence. By the time Fidel Castro visited Guinea in June 1976, much of the world recognized the MPLA as the legitimate government of Angola, and the trial of thirteen mercenaries in Luanda revealed the extent of intervention. In Conakry, Castro hailed the victory as a blow to global imperialism with a distinct regional importance (Figure 11.1). “In Angola,” he claimed, “the white mercenaries were destroyed along with their myth and so was the myth of the invincibility of the South African racists.”Footnote 2

Figure 11.1 “Angola is for the US imperialists an African Giron,” asserts this poster. Both Cuba and Angola viewed the MPLA’s victory over US-backed forces as a black eye for Washington, and many in the United States agreed. Southern Africa was the major arena for Cuban foreign policy for the next decade, and Southern African revolutionaries praised Cuban efforts opposing apartheid. Departamento de Orientación Revolucionaria, 1976.

During the prior decade, mercenaries emerged as one of the most persistent challenges to socialist revolution in Africa. In the Congo, white soldiers of fortune hailing from South Africa, Rhodesia, and former metropoles subdued rebellions and led the armies of Western-aligned governments. A myth of invincibility grew up around these forces as they won major victories with small numbers. When Cuba first began to envision a global revolutionary solidarity, it consciously sought to combat this mercenary challenge, which Castro described in his speech closing the 1966 Havana Conference as “one of the most subtle and perfidious stratagems of Yankee imperialism.”Footnote 3 Yet the reference was not merely to soldiers of fortune or mercenary companies like the one Mike Hoare assembled in the Congo. Rather, Castro targeted a range of figures working on behalf of Euro-American interests, including the forces of South Vietnam in 1966 and the failed exile invasion of Cuba at Playa Girón in 1961.

For Cuba, mercenarism represented the violent edge of neocolonialism: the coalition of Western advisors, local allies, covertly funded exiles, and soldiers-for-hire that limited the expansion of revolution through force. As the Cuban official Raul Valdez Vivo explained, “as long as there is imperialism, there will be mercenaries.”Footnote 4 This expansive definition never became widely adopted, but it reflected an inescapable reality. The wealthy United States and its powerful allies had a spectrum of options to respond to revolution. They used different forces in order to balance strategic necessity, material cost, and the effects on US prestige. Soldiers-for-hire offered Western governments ways to augment local forces while maintaining “plausible deniability,” but so did the use of covert forces and to some extent the arming of client states.Footnote 5

The Cuban concept of mercenarism sought to capture the calculations behind these options and was central to the militant Tricontinental worldview. Opposite mercenaries were revolutionary internationalist fighters, embodied in the figure of Che Guevara. Both these opposing forces consisted of foreign militants fighting alongside rebels or for governments, but they had different motivations and relationships to allied movements or states. Cuban leaders believed there was a distinctly unequal power relationship between mercenaries and their employers. Wealthy Western governments – or sometimes companies – retained anti-revolutionary agents to protect their interests either by direct payments (traditional mercenaries) or indirect benefits provided to local clients or client states, which included assurances of power, weapons, or other forms of aid. These local clients were motivated by self-aggrandizement, individual gain, or class promotion. By contrast, revolutionary solidarity drove the internationalist fighter, who sought to support the global struggle against empire and capitalism. Internationalist fighters operated not independently but rather as representatives of formerly colonized states or liberation movements (considered postcolonial governments in waiting). As Cuba’s internationalist fighters confronted mercenaries in Africa, the nation’s leaders emphasized identarian politics to further reinforce the distinction between Global North and South. Thus, by the 1970s, the internationalist fighter became a politicized symbol of cross-racial solidarity in the struggle against the necessarily interlinked “white mercenary,” imperialism, and neocolonialism.

Scholars have paid little attention to the ideologies that animate opposition to mercenaries and mercenarism. Yet thinking about the Castro government’s conceptualization of these phenomena and Cuba’s actions in Africa (see Map 9.1) reveal important elements about how a key branch of Tricontinentalism understood neocolonialism, internationalism, and the distinct power dynamics that damned the former while legitimating the latter. This chapter will consider this concept through four lenses: the Cuban response to the Playa Girón invasion, the extended challenge of mercenaries in the Congo, the Cuban intervention in Angola, and finally efforts to establish a body of law to control the use of mercenary force.Footnote 6 Taken together, these events reveal that, despite setbacks, Cuba’s internationalist fighters scored significant victories against mercenaries, particularly in Angola. But Cuba’s articulation of this spectrum of neocolonial violence, in which mercenarism was a key strategic part, struggled to gain support beyond Castro’s immediate allies. As events in the Congo and Angola raised global concern about freelance soldiers, states responded by drafting international laws that ignored Cuba’s expansive view and ultimately failed to resolve the challenge of mercenary force. Nevertheless, this Cuban conceptualization of mercenarism provides a window into Tricontinentalism: its global vision, concrete solidarity, and ultimate inability to change the structure of the international system.

Mercenaries and Tricontinental Solidarity

The shifting role of mercenaries in the modern world has been well documented by scholars.Footnote 7 The once common practice of hiring soldiers from elsewhere became controversial amidst the nationalist revolutions of the nineteenth century. Yet soldiers-for-hire did not wholly disappear, and mercenaries thrived as instruments of neocolonialism in Latin America.Footnote 8 They served as security for US companies – effectively extralegal armies – protecting and promoting national interests in between regular invasions and occupations by marines. In effect, Latin America anticipated the reality many postcolonial nations in Asia and Africa confronted during the Cold War. The Cuban concept of mercenarism evolved from this context, linking Cold War interventions to this longer history of foreign adventurism, filibustering, and economic domination.

The US-supported invasion at Playa Girón, known in English as the Bay of Pigs, led the Castro government to begin articulating its Tricontinental definition of mercenarism. On April 17, 1961, about 1,500 CIA-trained, anti-Castro exiles – the military wing of the Frente Revolucionario Democrático (FRD), self-styled as Brigade 2506 – landed at Bahía de Cochinos. When internal uprisings failed to materialize and President John Kennedy declined to provide US naval and air support, the Castro government overpowered the invasion force and captured about 1,200 members of Brigade 2506. Cuba subsequently tried and convicted the exiles for treason. Though many returned to the United States in exchange for prisoners and medicine in late 1962, a handful were executed.Footnote 9 The members of Brigade 2506 viewed themselves as representatives of a legitimate anti-Castro political movement – “freedom loving, Cuban patriots from all walks of life” – but Cuba labeled them mercenaries.Footnote 10 Though mercenaries remained undefined in international law, the Castro government used the term to delegitimize political opposition by linking it to outside meddling.

At the center of the issue was the question whether the members of Brigade 2506 acted on their own or on behalf of the United States. The Castro government believed the latter, laying out its logic in a collection of documents published in Havana as Historia De Una Agresión: El Juicio a Los Mercenarios De Playa Girón. The March 1962 indictment stated that the “mercenary brigade” was “trained, armed, directed, and paid by the imperialist Government of the United States of America.”Footnote 11 In fact, the CIA spent a year and $4.4 million molding disparate exile groups into a cohesive opposition.Footnote 12 Historia De Una Agresión took pride in uncovering the agency’s central role, detailing secret meetings from Havana to New York and a string of Caribbean training camps from Puerto Rico through Louisiana to Guatemala.Footnote 13 Collaboration with the imperial power immediately called into question the legitimacy and authenticity of the nationalism claimed by Brigade 2506, with the Cuban government arguing its members represented foreign interests. It noted that many members of the brigade planned to recover nationalized property. For Cubans, these counterrevolutionary goals meant that the invaders’ motives were “purely economic, purely at the service of a foreign country.”Footnote 14 For Castro, who warned of “mercenary armies” as early as 1960, these actions confirmed that opponents of the revolution had become paid agents of the United States determined to undermine Cuban sovereignty.Footnote 15

Cuba argued that the mercenary was a vital component of the neocolonial variety of imperialism practiced by the United States. The use of mercenary force allowed the United States and allied capitalist states to intervene against revolution with limited responsibility or liability.Footnote 16 Long familiar to Latin America, this practice became common across the 1960s Third World as decolonization ended European political control without dissolving the strong economic ties of empire. The first flashpoint in this new reality was the former Belgian Congo. When the country gained independence in June 1960 under the leadership of the outspoken Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, the powerful Anglo-Belgian mining company Union Minière du Haut-Katanga encouraged the secession of the mineral-rich southeastern province of Katanga under the businessman Moïse Tshombe. Tshombe accused Lumumba of communist sympathies and built a local gendarme under the leadership of Belgian officers, many of whom remained as mercenaries when colonial troops withdrew after independence. Worried Lumumba might lean toward the Soviet Union, Belgium and the United States quietly supported the assassination of the independent-minded nationalist by Katangan authorities in January 1961. Lumumba’s death caused international outrage, and fellow African leaders criticized Tshombe for seceding with the aid of white mercenaries, implying a betrayal of carefully intertwined racial and anti-imperial solidarities that helped bind together postcolonial states. On February 21, 1961, less than two months before the invasion of Cuba, the UN Security Council sought to calm tensions by urging foreign forces, including “mercenaries,” to withdraw from the Congo.Footnote 17

Cubans understood the regime’s victory at Playa Girón in this broader context. As the United States and its Western allies turned to mercenary force to police imperial boundaries where they had no direct control, the small Caribbean island fought back and won. Though isolated within its own hemisphere, where the Organization of American States (OAS) suspended the country because its “Marxist–Leninist government” was “incompatible with the principles and objectives of the inter-American system,” Cuba found new allies.Footnote 18 First among these was the Soviet Union, which aided the island and adopted some of its ideological language in order to needle the United States. In a March 1962 Security Council meeting, the Soviet ambassador claimed that the United States was “preparing within its own armed forces units of mercenaries to engage in a new intervention against Cuba.”Footnote 19 So too did Africans, Asians, and even North Americans see in small, embattled Cuba an example of resistance to Euro-American empire.Footnote 20 After Playa Girón, the Cuban regime posited that the nation had become “a symbol, an emblem of the anti-imperialist struggle.”Footnote 21

Isolated as it was, Cuba looked to this new international status to safeguard its revolution. The Soviet Union’s decision to deploy nuclear missiles on the island was, according to Che Guevara, linked to the insecurity created by “the mercenary attack at Playa Girón.”Footnote 22 Yet while the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis included a modicum of protection from US invasion, the revolutionary government envisioned a global movement of small states that could take the offensive against the United States in a way the Soviets were not willing to undertake. Detailed in other chapters within this volume, notably those by Hernandez and Hosek, Byrne, and Friedman, this struggle took Cuba into the orbit of the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization (AAPSO) and eventually led to the Tricontinental meeting in Havana of 1966. Key postcolonial leaders viewed European attempts to preserve economic and political power in their former colonies as analogous to the Latin American context, so they looked to Cuba as a model for reinforcing independence. The Moroccan leftist Mehdi Ben Barka predicted it would require either “Castroism” (revolution) or progressive political alliance to assure Africa would not become a neocolonial outpost for the Western powers.Footnote 23 In many ways, Cuba anticipated the problems its African allies would face. As a result, many states gradually adopted Castro’s conception of neocolonial force as Africa became the center of mercenarism.

The Mercenary and the Internationalist Fighter in the Congo

For Cuba, mercenary force was part of a larger problem: wealthy Western countries feared socialist revolutions in the Third World and could choose from a range of options to undermine them. In terms of military responses, mercenaries involved minimal commitment but transgressed international norms, which inspired Cuba’s liberal use of the term to denigrate US actions. Their sudden appearance in the Congo spoke directly to the Western decision to intervene in the Third World to protect economic and strategic interests. Postcolonial nations, long subsumed within Euro-American empires and lacking the resources to protect state sovereignty, struggled to respond to mercenary force. “Only the protégés of Yankee millionaires, representatives of slavery and wealth, representatives of fortune and privilege,” Castro said, “can obtain the support of a navy or an army.”Footnote 24 Even Soviet support failed to address this power imbalance, especially after the Cuban Missile Crisis illustrated the limits of Moscow’s commitment to confronting the United States. Cuban leaders therefore concluded that Third World states had to unite to confront this capitalist imperial challenge. They would organize within the Non-Aligned Movement and United Nations to draft new legal frameworks for the international system, but there was a need for active defense in the short-term. The result was what became known as the internationalist fighter.

Two main characteristics distinguished the internationalist fighter from the mercenary, as these terms were understood in radical Third World circles. First, the internationalist fighter was a socialist.Footnote 25 Mercenaries were motivated by greed and personal gain. Cubans believed anti-communism was generally either ideological window dressing for or intertwined with these base motives. Internationalist fighters, by contrast, were selfless. They fought to defend a global revolution waged by Third World socialists for national self-determination and the transformation of the international system. This “new revolutionary subject,” as Anne Garland Mahler describes it, was a direct refutation of the degradations of empire, including colonialism and neocolonialism.Footnote 26 “If the Yankee imperialist[s] feel free to bomb anywhere they please and send their mercenary troops to put down the revolutionary movement anywhere in the world,” Castro explained at the Havana Conference, “then the revolutionary peoples feel they have the right, even with their physical presence, to help the peoples who are fighting the Yankee imperialists.” He went on to pledge “our revolutionary militants, our fighters, are prepared to fight the imperialists in any part of the world.”Footnote 27

Second, as the quote above shows, the internationalist fighter operated in solidarity with the world’s oppressed people, not as a tool of domination. Governments employed mercenaries when they lacked legitimacy and sufficient support from local peoples to field a national force. Therefore, mercenaries fought against the best interests of the people (as revolutionaries saw it) on behalf of the Western powers, who either controlled client governments or undermined the independence of revolutionary states. In either case, mercenaries became agents of foreign domination. By contrast, the internationalist fighter fought alongside nationalist movements and governments in a bid to protect their rights to political and economic self-determination. At least in the ideal, this was a relationship of equals. Solidarity sought to bolster the nascent power of postcolonial governments.

The Congo became the first test of the worldview pitting the internationalist fighter against the neocolonial mercenary. Following the formation of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1964, the former head of secessionist Katanga, Moïse Tshombe, became prime minister. Faced with a rebellion by leftist supporters of the assassinated Lumumba, Tshombe turned to the West, specifically the United States, for aid. Fearing a “Commie field day in the Congo” but hesitant to intervene directly, Washington acted covertly.Footnote 28 It cajoled Belgium and employed mercenaries, repackaged as “military technicians” and volunteers, to prop up the weak government and defeat the Simba rebellion.Footnote 29 Recruited heavily from South Africa and Rhodesia (modern Zimbabwe) despite US preference for more Belgians and other Europeans, the mercenaries served as officers for the poorly trained Congolese army. They also formed the “cutting edge” of the government’s military response as part of the all-white 5th Commando unit under Colonel “Mad” Mike Hoare, an Indian-born Irish veteran of the British army who settled in South Africa and worked for Tshombe during the Katanga secession.Footnote 30 Though meant to operate quietly, the mercenaries gained notoriety in 1965 working alongside Belgian paratroopers to retake Stanleyville (Kisangani), where rebels held hundreds of European nationals hostage. The United States was essential in these efforts, providing funds, planning operations, and supplying transport for mercenaries and Belgian troops.Footnote 31 The CIA also arranged for air support and maritime interdiction of rebel aid, hiring Cuban exiles as contractors in order to limit US personnel to mostly advisory and technical roles.Footnote 32

Castro’s government believed the Congo confirmed its critique of US policy, including the mercenary nature of Cuban exiles, and provided an opportunity for the internationalist fighter. African governments were concerned about events in sub-Saharan Africa’s largest country, and aid from radical states like Algeria increased after white mercenaries became involved. The Tshombe government appeared weak. “Northeast Congo,” one US official noted in early 1965, “is really being held by only 110 mercenaries, supported by a peanut airforce.”Footnote 33 Washington officials worried a small band of “well-trained ‘enemy’ mercenaries could conceivably take it all back again.”Footnote 34 That such a small band was able to secure the large territory owed more to the exaggerated reputation the mercenaries acquired fighting poorly trained rebels over the past months than their actual military might. Believing the African continent ripe for revolution, Castro sent Che Guevara to organize a more effective rebellion.

Guevara found mostly frustration. With Cubans in the Congo at the joint request of the rebels and neighboring Tanzania, notes historian Piero Gleijeses, Guevara was constrained by respect for his hosts and the Congolese fear that public knowledge of the revolutionary icon’s presence might draw a forceful Western response. And Guevara found that Cuba had overestimated the potential of the rebellion. He complained of poorly organized troops, questionable leadership, and little fighting spirit. Finally, African countries proved willing to accept the Western-backed government in the Congo. When President Joseph Kasa-Vubu dismissed the controversial Tshombe and pledged to send all the “white mercenaries” home, the Organization of African Unity (OAU) withdrew aid from the Simba rebels. Tanzania, which served as Cuba’s forward operating base, made peace with Congo in order to focus its support for the anti-colonial revolution in southern neighbor Mozambique. It requested Cuba end its operations in the Congo, and Havana agreed.Footnote 35

Guevara’s Congo venture did not go as planned, but there are two points worth noting. First, it illustrated a distinct contrast between Cuba’s militant internationalism and Western intervention. Cuba’s internationalist fighters were there as allies in solidarity with the leftist rebellion opposing the Tshombe regime, which many Africans viewed with suspicion due to its political and economic ties to Europe. While Che’s reputation and Havana’s assistance provided Cuba with influence, it generally deferred to the desires of its African allies even when these desires clashed with Cuban priorities. This approach contrasted with US involvement, wherein Washington knew the “kind of leverage we have” over the Congolese government and was not above threatening to “cut aid or pull out some planes.”Footnote 36 While the United States did not always get its way, it achieved most of its goals in the Congo, in part by cajoling a reluctant Belgium to deploy troops and using powerful diplomatic tools to keep critical African governments at bay.

Second, Cuba did find partners in Africa, particularly among Lusophone revolutionaries. The strongest relationship developed with Amílcar Cabral and his successful Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC). Castro provided the party with important military and technical aid over the next decade, which likely encouraged Cabral to adopt Castro’s concept of mercenaries. By 1970, he identified “mercenaries of various nationalities” as responsible for training counterrevolutionary forces in the Republic of Guinea and criticized the “African mercenaries” who supported the Portuguese attack on the PAIGC’s exile home in Conakry.Footnote 37 Yet Cabral, though grateful for Cuban support, rejected Castro’s offers for larger numbers of troops even as Portugal turned to mercenaries. His emphasis on the role revolution played in the construction of the new nation precluded the involvement of foreign soldiers, as R. Joseph Parrott notes in Chapter 9. Castro accepted this logic, adapting the idea of the internationalist fighter to the needs of the ally in question. Thus, the many doctors and technicians sent to train PAIGC operatives would be the most important contribution Cuban internationalists would make to an African revolution before the 1970s.Footnote 38

A 1974 military coup that ended Portuguese colonialism created a new opportunity for Cuba. Castro had ties to the PAIGC’s ally, the MPLA, the most avowedly socialist but least successful of the major leftist parties fighting Portuguese rule.Footnote 39 Over the next year, the MPLA vied militarily for control of Angola with two opposing parties linked to the West. The Cuban government agreed to provide aid to the Forças Armadas Populares de Libertação de Angola (FAPLA), the party’s armed wing, when competition turned increasingly toward military confrontation. As the November transfer of power neared, it became clear that the MPLA’s enemies were slowly uniting into a coalition supported by the Congo, South African troops, US weapons, and hired soldiers. Militant Tricontinentalism and the internationalist fighter finally had the chance to confront a Western intervention.

Angola and the Defeat of the “White Mercenary”

The sudden end of Portugal’s empire presented a number of geopolitical challenges. Scholars often explain US involvement, which aided the Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola (FNLA) and the União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (UNITA), as a response to the arrival of Cuban forces in the country. But as Piero Gleijeses’s exhaustive research shows, the CIA and South Africans were active in Angola before Cuba deployed its internationalist brigades in November 1975. President Ford authorized a covert war against the MPLA on July 18, 1975, beginning with a CIA investment worth $24.7 million.Footnote 40 Wary of deploying troops following the Vietnam War, US strategy again looked to allies and proxies, including mercenaries recruited to fight in northern Angola. Once it became clear that the United States and South Africa were in the process of intervening in Angolan affairs, MPLA head Agostinho Neto requested Castro’s assistance. Cuba responded with what historian Jonathan Brown describes as “religious fervor.”Footnote 41

Cuban aid proved invaluable in helping the MPLA establish control of Angola. The few dozen advisors present in August 1975 grew to 500 officers and instructors by October. They brought with them rifles, trucks, and pilots to fly the MPLA’s small air force. Supported by this Cuban assistance, the MPLA won some early victories, but the South African intervention aiding UNITA in the south and FNLA forces backed by the CIA and Portuguese mercenaries in the north pressed toward Luanda. In response, Cuba sent two planeloads of troops to fight alongside the MPLA.Footnote 42 With Soviet aid, Cuban troops helped the MPLA hold the capital of Luanda until independence on November 11. They pushed back two more offensives over the following months as the number of Cuban troops swelled past 15,000. Increased military success, combined with a strong global reaction to South African intervention, turned the tide in favor of the MPLA, which gained widespread recognition as Angola’s ruling party by February 1976.

Cuban solidarity played a vital role in reinforcing MPLA sovereignty in the face of foreign intervention. The presence of internationalist fighters was no secret; news reports and sympathetic Westerners remarked on their presence, the latter differentiating them from mercenaries by referring to “Cuban volunteers.”Footnote 43 The key difference was their identification with the MPLA and its cause. Neto argued they were “comrades who have felt the problems of our revolution, of our struggle, the problems of our people.”Footnote 44 American officials also noted the foreign fighters’ impact. CIA Director William Colby remarked cynically that Cuban soldiers had become the “mercenaries of the Communist world.” Yet even Washington officials recognized that the motivation, organization, and public avowal of the Cuban deployment set them apart. “These are not mercenaries,” the CIA’s Africa chief reminded Colby, “they are regular Cuban troops.” All admitted they had a powerful impact on events in Angola.Footnote 45

By contrast, the American-backed intervention proved a disaster. The covert aid provided by the United States became a global spectacle after South Africa intervened. The alliance between Angolans and the apartheid state elicited immediate regional condemnation. The sudden appearance (and capture) of white mercenaries, whom one MPLA official noted were “frequently” encountered in battle, caused additional consternation.Footnote 46 A US Congress still smarting from the Vietnam War moved to constrain a policy that lacked legitimacy, passing the Clark Amendment that barred covert activities in Angola without prior legislative approval. South Africa soon withdrew its troops, though it continued to support UNITA’s guerrilla war for over a decade. The MPLA held a trial in Luanda for thirteen captured mercenaries, including three Americans, that heightened Western embarrassment by publishing details of the failed intervention.

Cuba embraced events in Angola as not just a blow to US empire but also as a defeat of mercenary force, dramatized by the Luanda Trial. Cuba’s global vision of mercenarism and the internationalist response found its clearest explanation in the publication Angola: Fin Del Mito de Los Mercenarios (1976), a sustained analysis of the Western intervention written by Raul Valdes Vivo, the head of the General Department of Foreign Relations of the Cuban Central Committee of the Communist Party.Footnote 47 Taking an expansive view, Vivo identified a spectrum of US agents: Israel, “traitorous Arab rulers,” South Vietnam, and UNITA’s Joseph Savimbi. But he argued that Angola represented a new stage in US policy after its inglorious defeat in Vietnam. Washington resorted to mercenaries, asserted Vivo, “so as to avoid the need for a full frontal attack by imperialism.”Footnote 48

While Vivo simplified the Angolan situation, he was accurate in many respects. White mercenaries were just one component meant to strengthen the resolve and ability of the FNLA and UNITA alongside assistance from the CIA, Zaire (formerly Congo), and South Africa. US policymakers were more reluctant to use soldiers-for-hire than they had been a decade prior, but the shadow of Vietnam pushed them in that direction. When one military official recommended increasing CIA operatives to help reinforce anti-MPLA forces, he was quieted with the rhetorical “General, did you ever hear of Laos?” Strategy immediately shifted to mercenaries. Much like earlier in the Congo, the United States sought to shape events with minimal involvement, including reaching out to former Portuguese colonials who “have a heart for Angola and want to help out.”Footnote 49 Portugal proved reluctant to assist these efforts, and Brazil flatly refused, leaving the United States to depend on local proxies and South Africa. The United States funded some mercenaries alongside France, though both operated more subtly than they had in the Congo.Footnote 50

As a result, the mercenary network that cohered in Angola was more diffuse and less professional than a decade prior. Klaas Voß argues that Angola was the beginning of a shift in American recruitment strategies, from the organized method that partially reproduced colonial relationships to a “laissez-faire approach” that depended on “recruitment agencies and mercenary networks.”Footnote 51 One (in)famous node in this network was Soldier of Fortune. Founded in 1975 after former army officer Robert K. Brown visited Rhodesia, the magazine became a clearinghouse for information about mercenaries in Southern Africa, including recruitment notices.Footnote 52 Vivo interviewed the captured US mercenary Gary Acker, who found his way to Angola through his own ad in the magazine. A Vietnam veteran with anti-communist views, he gravitated to the mercenary life after failing to find a peacetime job. While such economic motivations were real, historian Gerald Horne contends that many veterans like Acker also saw Angola as an opportunity to flip the script from Vietnam. They welcomed the chance to fight against real communists after Cuban participation became public.Footnote 53 This anti-communist connection led Vivo to suspect CIA connections to Soldier of Fortune and the recruiting offices that appeared in Western nations.Footnote 54 While the United States certainly funded mercenaries in Angola, the government apparently did opt for the “laissez-faire” approach. Records show less of the recruitment, coordination, and transportation that typified the Bay of Pigs invasion or the Congo episode.Footnote 55

While reinforcing some Cuban arguments about mercenarism, the Angola conflict also promoted a subtle change in the Cuban approach to the topic. Castro’s claim that Angola had witnessed the destructions of “the white mercenaries … along with their myth” implied a new emphasis on race in Cuban ideas of Tricontinental solidarity.Footnote 56 This shift in Cuban rhetoric directly reflected an increased involvement in Africa. Events in the Congo during the previous decade created an aura of invulnerability around the white soldiers drawn heavily from minority-ruled Southern African states. It began with the Katanga secession but transformed into myth when the mercenaries, rarely numbering more than 1,000, defeated the Simba rebellion.Footnote 57 African concern with white mercenaries served two conflicting purposes. On the one hand, it linked small bands of unaffiliated soldiers with institutional power associated with the colonial system, subconsciously attaching the mercenary to a long history of martial success. Simultaneously, this rhetoric united a diverse set of majority-black African states behind an anti-imperial cause. It also enabled them to argue that mercenaries exacerbated racial strife, which Westerners feared would harm their standing on the continent.Footnote 58 The myth provided white mercenaries with exaggerated power in the 1960s, but their defeat in Angola provided a rallying cry for anti-imperial solidarity.

Cuba’s rhetorical shift is important because the Castro government had previously resisted making race central to Tricontinentalism or its concept of mercenarism. Not only were light-skinned Cuban leaders, including Argentinian Che Guevara, sensitive about race, but this formulation excluded local collaborators like Tshombe and the FNLA. In the Congo, Guevara criticized the rebels for blaming their losses on white mercenaries rather than fellow Africans. Mercenaries from Belgium and Southern Africa trained and led the army, but much of the fighting was undertaken by formidable Congolese soldiers in the employ of a black-led government.Footnote 59 When the Cubans finally withdrew, Che worried less about the challenge posed by the handful of whites than the fact that the rebels would have to confront “mercenary” Africans acting as agents of imperialism and neocolonialism.Footnote 60

Still, Cuba knew race had the power to promote solidarity, especially at the interpersonal level. Victor Dreke, Guevara’s Afro-Cuban second-in-command in the Congo tasked with recruiting Cuban volunteers, recalls being told “the compañeros were to be black – ‘very black’.”Footnote 61 As Dreke’s comment implies, the increased emphasis on the racial elements of solidarity emerged as Cuban collaboration with Africans increased. Allies like Cabral sought to balance race and ideology in conceptualizing revolution, and his statement that Cubans were “a people that we consider African” likely encouraged the shift.Footnote 62 Moreover, African opposition to minority rule provided a ready source of solidarity partially defined along racial lines. It had been the public revelations about the South African intervention, after all, that undermined UNITA and the FNLA while forcing African states to overwhelmingly condemn the intervention.

Invoking this racialized specter aligned Cuba with African allies and further differentiated its soldiers from mercenaries. Vivo’s Fin Del Mito de Los Mercenarios emphasized this new racial frame. He dismissed Soldier of Fortune as bigoted, one node in the network connecting Washington and its “mercenary thugs” to the hated minority states of the continent.Footnote 63 The magazine adopted a rhetoric of nominal racial equality, but its fawning coverage of Rhodesian and South African soldiers reinforced the mythic power of armed whites, which Vivo compared to depictions of Tarzan in “US racist literature.”Footnote 64 Destroying this threat struck a blow against empire and white dominance. “The 30 year-long myth of the white mercenaries, arriving by the legion or emerging suddenly from nowhere as vast armies,” Vivo declared, “was destroyed in a matter of three weeks, and neocolonialism lost one of its sharp fangs.”Footnote 65 Castro declared Angola no less than the Playa Girón of Africa; there was now proof that “white mercenaries” were subject to defeat and that the mighty South African government was vulnerable.Footnote 66

Wedding aspects of black self-determination to the socialist revolution served one final purpose. Race had long been a mark of status in Cuba, but officials downplayed domestic divisions by promoting a “Marxist exceptionalism” that claimed racism to be impossible in the socialist state.Footnote 67 This rhetoric did not erase inequalities. Nor did it fit comfortably with the mindset of African and Asian leaders, whose non-white identities became increasingly central to their national oppositions to empire. Aligning itself with African states against white invaders encouraged the Castro government to embrace an Afro-Cuban identity. Vivo captured the idea in striking prose:

In Angolan soil, the soil of many of their ancestors, remain the bodies of the internationalist fighters killed in combat, followers of Che Guevara, eternal heroes of two homelands, giving new life to the Latin-African roots of which Fidel spoke.Footnote 68

As Mark Sawyer observes, “involvement in Angola opened the issue of race.”Footnote 69 The embrace of this Afro-Cuban identity further tied the nation to the global anti-imperial movement while realizing – abroad if not always at home – the power of a multi-ethnic state.Footnote 70 Whereas mercenaries were outsiders intent on prolonging foreign domination, Cuba claimed a diasporic solidarity opposed to alien white empires and racism writ large. This formulation of mercenarism addressed foreign and domestic priorities of the Cuban state but ultimately limited its ability to shape wider global norms.

Mercenary Force and International Law

If Angola in 1976 was a prime example of Tricontinental solidarity and the evolution of the Cuban concept of mercenarism, its aftermath demonstrated the limitations of the philosophy, namely its inability to win sufficient support to transform the international system. Cuba and the MPLA sought to use the Luanda Trial to legitimize its power and set legal precedent against foreign intervention and the use of mercenaries. With support from African governments, the MPLA’s Ministry of Justice invited approximately fifty-one individuals from thirty-seven countries to make up the International Commission of Enquiry on Mercenaries. Headed by André Mouélé of the Congo-Brazzaville, the commission included among its members three Cubans including Vivo, two Soviets, and three Americans from the National Conference of Black Lawyers. The MPLA charged the commission with drafting a statement on the legal status of mercenaries and monitoring the trial, which most analysts deemed politicized but procedurally fair. More troubling, perhaps, these observers concluded that “being a mercenary” was not a legally recognizable crime. They agreed that the international community should intervene to solve this problem.Footnote 71

International law had indeed been slow to tackle the problem of mercenaries. Though they fell out of favor during the 1800s when nationalism became the preferred tool for recruiting armies, mercenaries remained valuable contributors to small, distant wars and found new state imprimaturs under guises like the French Foreign Legion. Few legal documents mentioned mercenaries. The 1907 Hague and 1949 Geneva Conventions assumed such soldiers – without using the term precisely – to be lawful combatants and privy to the same humane treatment as other prisoners of war.Footnote 72

After Playa Girón in 1961, Cuba intermittently sought to institutionalize the vague distaste for mercenaries into international law, ultimately hoping to declare foreign intervention by mercenaries illegal. Attorney General Jose Santiago Cuba Fernández cited elements of the 1928 Havana convention, the 1936 Inter-American Peace Conference, and the charters of the UN and OAS to claim the United States violated international law. These documents discouraged indirect intervention in the affairs of sovereign states. Fernández’s choice of the emotionally powerful term mercenaries dramatized the extent to which the United States had funded and guided the exile invasion.Footnote 73 Cuba ultimately convicted the exiles of treason, but they structured the colorful hearings around mercenarism in an attempt to try the United States in “the Court of the Peoples of the world.”Footnote 74

Castro argued in 1962 that the lack of international law regulating mercenarism allowed the use of mercenaries to continue.Footnote 75 Thus, Cuban rhetoric and the multilingual publication of documents like Historia De Una Agresión and Vivo’s Fin Del Mito de Los Mercenarios sought not just to win propaganda victories but also to influence international law. In this respect, these publications and gatherings like the Havana Conference were part of the larger anti-imperial project that sought to forge solidarity in order to integrate concerns of the Global South into an international system built on European and North American priorities and precedents. As Vijay Prashad notes, the Tricontinental “rehearsed the major arguments – so that they could take them in a concerted way to the main stage, the United Nations.”Footnote 76 Cuba wanted to put neocolonial intervention on the docket in New York. Yet by defining mercenaries as products of specific ideological and (later) racial contexts, Cuba delimited the legal value of the concept it sought to universalize.

Rather, it was African states that led the push to revise international law to discourage the use of mercenaries. Events in the Congo unnerved many of these young nations, especially after the munity of white mercenaries in 1966 threatened regional stability. The next year at Kinshasa, the OAU passed a resolution demanding the withdrawal of mercenaries from the Congo.Footnote 77 Events such as the Biafran secession from Nigeria, which led to a civil war in which mercenaries played a small role, reinforced the need for change as governments on both the left and right felt threatened. As a result, the OAU, meeting in Addis Ababa in 1971, drafted a convention against mercenaries that was finalized six years later.Footnote 78 It declared that mercenarism was a crime that could be “committed by the individual, group or association, representative of a State and the State itself who with the aim of opposing by armed violence a process of self-determination stability or the territorial integrity of another State” engage in a number of different actions.Footnote 79 The convention did not use the politicized language of intervention favored by Cuba, but the OAU went beyond merely defining the mercenary as an individual and articulated a definition of a crime for which states might be guilty. It further demanded that states prohibit within their territories “any activities by persons or organisations who use mercenaries against … the people of Africa in their struggle for liberation.”Footnote 80 This formulation directly responded to the implicitly racialized use of mercenaries by and from the white minority regimes that aimed to frustrate self-determination of postcolonial states. These OAU efforts were a catalyst for international action before the Luanda Trial.

The UN responded to OAU efforts by formulating the first truly intercontinental definition of a mercenary. Begun in 1974 and adopted in 1977, Article 47 of the Additional Protocols to the 1949 Geneva Convention stripped these figures of the legal protections extended to legal combatants and prisoners of war.Footnote 81 But it lacked much of the language of the OAU convention, specifically the attempt to hold states accountable for employing mercenaries. These more radical elements present in the OAU text fell victim to UN deliberations, where the need for majority approval empowered moderate states and allowed powerful Western countries to promote acceptably banal language. Blessing Akporode Clark, Nigeria’s Permanent Representative to the UN, described Article 47 as a “compromise text” that owed much to the US delegation, “who had conducted the negotiations leading to the adoption of the new article.”Footnote 82 International law finally ruled on mercenaries, but it did so in a way that failed to address the inequalities of power that led to their use. Cuba was deeply disappointed. As Minister of Foreign Affairs Juana Silvera explained, his country favored “an exact definition and prohibition that would clearly reflect the truth of mercenary activities, the aims of which are to hamper and thwart the struggle of peoples to free themselves. These aims,” Silvera continued, “reflect political interests of the imperialist countries and their lackeys, which have … ignored this truth, thus helping to build up the mercenary system.”Footnote 83 Such an overtly political definition of mercenary activity was unlikely to gain traction, but the reality was the OAU conventions fared only marginally better because they targeted practices used by both the Western powers and their Third World allies.

Agitation against mercenary force became an ongoing theme at the UN as the practice grew increasingly common. Ten years after passage of the UN convention, the Red Cross lamented, “there has scarcely been any conflict involving military operations in which the presence of mercenaries has not played a part in one way or another.”Footnote 84 As a result, efforts increased to address the recruitment, use, and financing of mercenaries. African states again took the lead. In December 1979, Nigeria pushed successfully for a new convention against the recruitment, use, financing, and training of mercenaries. Likely referencing the Western obsession with the violent international struggle of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, Clark explained that “efforts by the international community to reduce the problem of international terrorism cannot be said to be complete without focusing attention on the menace these soldiers of fortune bring to many nations in Africa.”Footnote 85 A month later, at the start of its new session, the General Assembly formed a committee to draft the new convention, with nine of the thirty-five members coming from African nations. Cuba was not initially selected as a member of the committee by the Latin American group of nations. But just a few days after the committee was announced, Panama, under the control of the socialist-leaning Democratic Revolutionary Party, withdrew in favor of Cuba.Footnote 86

Cuba seemed to have finally gained the international standing to promote its theory. The successful defense of the MPLA in Angola affirmed Cuba’s claim to be a revolutionary state with global aspirations. Its troops remained in Angola while doctors and technicians streamed in to help build the infrastructure of the state. In late 1977, Cuban troops again deployed to the African continent, this time to protect the communist Derg in Ethiopia from a Somali invasion.Footnote 87 As Paul Thomas Chamberlin shows in Chapter 3, this was the apex of Tricontinental solidarity. Cuba parlayed its standing among leftist Third World governments to finally take the chairmanship of the Non-Aligned Movement beginning in 1979 with hopes of moving the loosely organized conference in more radical directions. With nominal leadership of the UN’s largest voting bloc, Cuba seemed poised to shape the conversation on mercenarism. Yet Cuba was ultimately frustrated. This history illustrates the extent to which Cuba’s expansive view of mercenarism – and Tricontinentalism itself – struggled to gain and maintain widespread support.

Cuba had lost its position as head of the NAM by the time the two working groups of the drafting committee consolidated their efforts in 1984. Cuba struggled to steer the loose conference, stymied on various occasions by conservative oil states in the Gulf region, moderates like Nigeria, and even by allies like Vietnam whose zeal for revolution took a backseat to its interest in managing regional and global politics. Cuba’s UN vote against censuring the Soviet Union for its invasion of Afghanistan further eroded its standing. Yet the country remained committed to Tricontinentalism, and the Cuban delegation contributed a proposed draft convention to the committee that situated the problem of mercenary force squarely within this context. The preamble identified mercenaries as antagonists of liberation and decolonization, citing earlier efforts by the OAU and NAM to promote “progressive development of international law towards regarding mercenarism as international crime.” Cuba’s expansive definition of mercenarism provided an alternative to the individual-focused UN Additional Protocols of 1977, declaring that states, along with their representatives and agents, were culpable for the crime of mercenarism if they organized, financed, supplied, equipped, trained, promoted, or employed forces that oppose national liberation, independence, or self-determination movements.Footnote 88 This language drew on and expanded the 1977 OAU convention, but Cuba’s draft garnered sparse support. As deliberations stretched on, the financial crisis of the 1980s led to the decline of G-77 power and forced many UN-member states to court donations from Washington and the international financial institutions it controlled. There was little appetite for a radical challenge to international norms, even when the subject was mercenaries.

The committee’s final draft neglected most of the Cuban language. The focus was on mercenaries as individuals and the goal of maintaining “friendly relations” between states, rather than protecting liberation movements. The Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries adopted in 1989 did update the Additional Protocols of 1977 by adding a second definition of mercenaries that recognized them as a threat to the constitutional order and territorial integrity of a state. Still, the UN maintained a narrow vision of who constituted a mercenary: an outsider “neither a national or resident of the State” in which they were operating, who acted outside official state forces.Footnote 89 The Cuban definition of both exile invasions and foreign-backed proxy governments as examples of a broader, neocolonial concept of mercenarism had no support from international law. The convention discouraged states from recruiting, using, financing, or training mercenaries, but all the offences specified in the convention were acts committed by persons.

Ironically, even this watered-down convention failed to win much support. After nearly three decades, only thirty-six states had ratified it by 2021. The United States, France, and Britain – major purveyors of mercenary force from the Cold War to the present – are not among them. Neither is Angola, which signed the convention in 1990 but never ratified it. Three years later, the country became a launching point for a generation of soldiers-for-hire. Still involved with its prolonged civil war with UNITA, the MPLA government – without Cuban troops thanks to the end of the Cold War – employed the private, South Africa-based military company Executive Outcomes (EO) to help it defend major assets, including oil infrastructure operated by multinationals like Gulf Oil.Footnote 90 Cuba’s Tricontinental vision of international fighters opposing capitalist mercenaries was lost. In the following decades, employment of these corporate security contractors became common as states like Angola chose to defend elite political and economic interests rather than continue down the path of Tricontinental revolution.

The private contractors employed by EO and similar companies, which some observers see as modern mercenaries, fit well with the competitive neoliberalism of the 1990s.Footnote 91 The delimited, much ignored anti-mercenary laws formulated after the Luanda Trial did little to slow the growth of these companies, and prosecutions of all but their worst excesses remain rare.Footnote 92 In the twenty-first century, the United States used dozens of private firms such as Blackwater to provide security, training, and operations support during its extended wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.Footnote 93 Though the underlying logic had changed from anti-communism to anti-terrorism, essential calculations about cost and culpability remained constant in producing these new coalitions between Western forces, local allies, and soldiers-for-hire. So too did this coalition both respond to and encourage networks of opposing transnational fighters, though the identarian fundamentalism of groupings like the Islamic State contrasted sharply with the Tricontinentalism of the Cold War era.

Conclusion

As a radical, revolutionary nation, Cuba conceptualized mercenarism – understood to be an explicit form of imperialism – to help organize and assist Third World peoples to challenge colonial and neocolonial domination. As a consequence of what Mahler calls “the totalizing perspective,” anyone acting against Cuba or its Tricontinental partners was a mercenary.Footnote 94 Dreke summed up this global contest in 2017: it was as simple as capitalists versus socialists.Footnote 95 Emergent formulations of international law viewed mercenaries more simply, as individual legal violations rather than components of a larger system aimed at policing the edges of North-South power disparities. Cuba’s broad formulation of mercenarism and inherently ideological motivations proved controversial even at the time. This contention prevented the adoption of these ideas even as a majority of African states sought to rein in this destructive and unpredictable practice. Tricontinental thought was too radical to achieve a consensus among Third World states, let alone to reshape the rules of international law. With no sufficient legal apparatus limiting the use of mercenaries or intervention in the Global South, Tricontinental advocates – and subsequent generations of anti-imperialists – responded to force with force.

This does not mean that Cuban soldiers became mercenaries for the left. Christine Hatzky, among others, argues that the Cuban government profited from its deployment of military and civil forces in Angola, making them mercenary in nature.Footnote 96 Hatzky is correct that Angola paid for decades of Cuban assistance, and internationalist deployments became a point of national pride for Castro’s government, almost mythic in nature. However, these payments were considered parts of Tricontinental solidarity, in which marginalized states pooled their limited resources to fight a common revolution. Cuba lent military and civil assistance to Angola, but it required payments to subsidize these deployments. Two points argue against understanding this as a mercenary relationship. First, Hatzky herself admits that most Cubans were motivated by solidarity and commitment to the revolution, not by the possibility of individual gain.Footnote 97 Exchanges occurred between governments as part of international diplomacy. Second, understanding Cuban concepts of mercenarism reveals that the limited inequalities of power between the parties prevented the creation of such a dynamic. Cuba and Angola negotiated their relationship in ways that allowed each country to benefit.Footnote 98 Cuba could not bankroll its foreign mission, but neither could it dictate terms. This arrangement contrasts with both traditional mercenary relationships wherein money buys loyalty and the expansive definition that Cuba applied to the United States, whose wealth allowed it to provide generous aid but wielded this power to control clients such as Congo and South Vietnam.

This is not to say that Tricontinental solidarity was wholly superior to mercenary force. Internationalist fighters thrived in the postcolonial era because of their role within the militant ideological conflict of the Cold War. When the conflict ended, the internationalist fighter became untenable even as US empire remained. Cuba began reducing its Angolan deployment after the MPLA claimed victory over South African troops at Cuito Cuanavale, but it is no coincidence that the final withdrawal occurred between 1989 and 1991. Moreover, the departure of Cuban and other foreign troops did not resolve the factors that led to internal unrest and the use of mercenaries; indeed, decades of Cold War conflict exacerbated it. Especially in Africa, leaders such as Angola’s José Eduardo Dos Santos grew dependent on foreign soldiers – be they politically inclined or paid – to prop up governments whose legitimacy was limited by political, regional, and historical divisions. Like mercenaries, internationalist fighters provided weak governments with an effective fighting force whose allegiance was only tangentially related to domestic competence and whose foreign makeup militated against the creation of competing domestic power blocs. It is this reality that helps explain Angola’s shift toward corporate mercenaries after the Cold War ended. As a result, Che and his fellow internationalist fighters have become largely symbolic, while mercenaries soldier on.