Summations

-

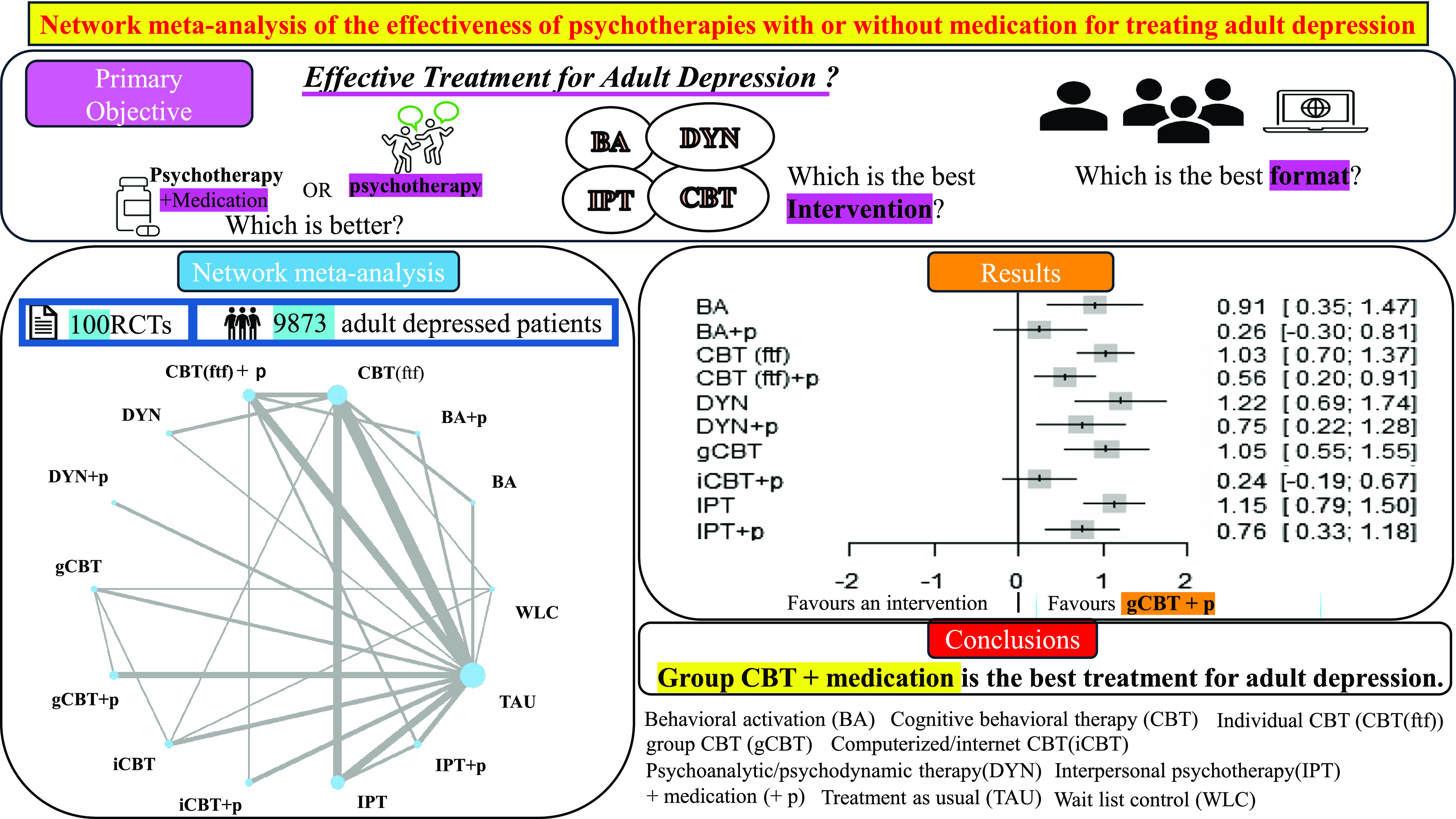

In patients with depression, a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy demonstrated superior efficacy compared to psychotherapy alone.

-

The magnitude of improvement varied depending on the baseline severity of the depressive symptoms.

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy in a group setting, when supplemented with pharmacological treatment, appears to be the most effective intervention for adult depression.

Considerations

-

Among the participants assigned to the psychotherapy-alone group, there was a probability that less than 50% utilised pharmacotherapy.

-

The proportion of participants with mild depression at baseline was relatively smaller than that of those with moderate or severe depression.

-

In our study, we compared only individual face-to-face formats of psychotherapy other than cognitive behavioural therapy.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO 2023), depression is one of the most common conditions, affecting 3.8% of the global population. It presents a severe challenge, and individuals who experience depressive episodes may encounter difficulties in their daily lives, leading to significant economic and social costs (Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Fournier, Sisitsky, Simes, Berman, Koenigsberg and Kessler2021). Moreover, the severe consequences of untreated or inadequately treated depression can increase the risk of suicide, emphasising the need for accessible and effective interventions.

Treatments for depression can be broadly categorised into pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. In daily clinical practice, many individuals with depression are treated with psychotherapy combined with medication, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines (APA 2019; NICE, 2022). A combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy has been reported to be more effective than psychotherapy alone(Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Warmerdam and Andersson2009; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Andersson, Beekman and Reynolds2014; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Noma, Karyotaki, Vinkers, Cipriani and Furukawa2020). Linde (Linde et al., Reference Linde, Rucker, Sigterman, Jamil, Meissner, Schneider and Kriston2015) attempted to distinguish between different types of psychotherapy and compare psychotherapy alone with the combination of psychotherapy and medication in their network meta-analysis. However, their results were limited because they included only three combination therapies from a single trial and could not assess the comparative effectiveness of psychological treatments.

Therefore, to address these shortcomings, we conducted a network meta-analysis to compare the effectiveness of common psychotherapies among adult patients with depression and determine which combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy is the most effective.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We conducted a network meta-analysis of only published RCTs. Participants were adults (≥ 18 years) with depression diagnosed using any of the following internationally recognised diagnostic criteria: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III: (American Psychiatric Association 1980), DSM-IV: (American Psychiatric Association 1994), DSM-5: (American Psychiatric Association 2013)) or the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Endicott and Robins1978).

The exclusion criteria were adolescents aged<18 years and studies involving older people. Patients with subclinical depression; those with ante-/peri-/postnatal depression, a mood disorder, adjustment disorder, affective disorder, or stimulant-dependent depression; those with comorbidities, such as bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, schizophrenia, organic brain syndrome, or cognitive impairment; and those with active suicidal ideation were excluded. We also excluded studies in which the participants had a specified background. Therefore, studies on immigrants, prisoners, caregivers, veterans, war victims, and individuals with marital discord were excluded. Studies targeting only patients in remission from depression, inpatients and those living in nursing homes, and studies in which all participants had the same psychiatric issues (e.g. alcoholism, drug abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], borderline disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or eating disorder) or medical conditions (e.g. coronary artery disease, cancer, pain, inflammatory bowel disease, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], or multiple sclerosis) were excluded.

We selected RCTs comparing psychotherapy (i.e. cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), behavioural activation (BA), psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy (DYN), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT)) for depression with intercomparison and with wait list control (WLC) or treatment-as-usual (TAU), including medication. The definitions of each included intervention are as follows:

Behavioural Activation: It is a therapeutic approach that theorises depression usually stems from withdrawal from enjoyable and meaningful activities. BA aims to counteract depression by systematically scheduling and monitoring activities that promote pleasure and achievement (Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Dobson, Truax, Addis, Koerner, Gollan, Gortner and Prince1996)

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy: It is a form of psychotherapy first developed by Beck (Beck, Reference Beck1964). The therapy is based on the premise that psychological factors, such as problematic behaviours, emotions, and thought patterns, interact with each other. Therapists collaborate with clients to identify negative thoughts, replacing them with more balanced and realistic ones through a process known as cognitive restructuring. Additionally, therapists encourage clients to engage in more positive and rewarding activities, a technique termed BA, to improve mood and reduce avoidance behaviours. CBT also involves assigning homework and gradual exposure to feared situations or difficulties that clients have been avoiding, with the aim of changing unhelpful thought patterns and behaviours contributing to emotional distress or problematic behaviours.

Psychoanalytic/psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Psychodynamics is the study of the underlying psychological forces influencing human behaviour, emotions, and mental processes, with a focus on unconscious motives and conflicts. It originated from the psychoanalytic theory by Sigmund Freud (Freud, Reference Freud1900). Psychoanalysis is the traditional intervention based on psychodynamics. Psychoanalytic psychotherapy typically requires long-term treatment conducted several times per week, with the patient lying on a couch and the therapist interpreting unconscious material to facilitate insight and emotional healing. Psychotherapies that follow a psychoanalytic tradition are referred to as psychodynamic psychotherapy and supportive-expressive (SE) psychotherapy. Psychodynamic psychotherapy usually takes place once or two times a week, with the patient sitting up. SE psychotherapy is a current form of dynamic treatment that incorporates clinical research methods. The goals of psychotherapies based on psychodynamics are client self-awareness and understanding of the influence of the past on present behaviour (Corsini et al., Reference Corsini and Wedding2011).

Interpersonal Psychotherapy: It is a time-limited and symptom-focused therapy developed in the 1970s by Gerald Klerman and Myrna Weissman primarily (Weissman et al., Reference Weissman and Klerman2015) to treat nonpsychotic depression in adults. The core principle of IPT is that depression usually arises within the context of interpersonal relationships. IPT targets four specific problem areas – grief, interpersonal disputes, role transitions, and interpersonal deficits – that are regarded as triggers for depressive episodes. The therapist helps patients understand the relationship between their depressive symptoms and these interpersonal issues and focuses on developing interpersonal skills to effectively manage or resolve them, thereby facilitating recovery from the current depressive episode (Corsini et al., Reference Corsini and Wedding2011).

Rational emotive behavioural therapy (REBT) (Ellis, Reference Ellis1957) was excluded because of the different theoretical approaches and therapeutic techniques. CBT and REBT share the common goal of symptom reduction through cognitive restructuring, based on the theory that thoughts and behaviours influence emotions. However, they differ in the following points. REBT focuses on directly challenging irrational beliefs and thoughts, aiming to transform them through logical arguments and counterarguments. In contrast, CBT focuses on identifying unhealthy cognitive patterns (cognitive distortions) and guiding individuals toward more realistic and balanced thinking using objective evidence and empirical information. Third-wave, transdiagnostic, culturally adapted, and depression-preventive psychotherapies were excluded. Exercise therapy was excluded because it is not classified as a form of psychotherapy.

CBT is the most extensively studied and frequently reported psychotherapy for depression (Barth et al., Reference Barth, Munder, Gerger, Nuesch, Trelle, Znoj, Juni and Cuijpers2013; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Quero, Noma, Ciharova, Miguel, Karyotaki, Cipriani, Cristea and Furukawa2021). Therefore, regarding CBT, we categorised groups by format as follows: face-to-face individual therapy (CBT (ftf)), group therapy (gCBT), and internet-based or computerised therapy (iCBT), and compared them. We included guided self-help iCBT when the research staff contacted patients individually and directly, including by telephone or email. We excluded iCBT when it was completely self-help, even if patients received technical support or a guide via automatic message because iCBT without individual support is inferior to supported iCBT (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson and Cuijpers2009; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Noma, Karyotaki, Cipriani and Furukawa2019; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Owen, Richards, Eells, Richardson, Brown, Barrett, Rasku, Polser and Thase2019). Bibliotherapy was excluded because it has a lower attrition rate than other psychological therapies (Handbook of Non Drug Intervention (HANDI) Project Team 2013). In contrast, iCBT is reported to have equivalent adherence to CBT (ftf) (van Ballegooijen et al., Reference van Ballegooijen, Cuijpers, van Straten, Karyotaki, Andersson, Smit and Riper2014; Treanor et al., Reference Treanor, Kouvonen, Lallukka and Donnelly2021) and were included in this comparison. Therefore, we included iCBT as interventions but excluded bibliotherapy from the intervention. Individual face-to-face BA, IPT, and DYN were included in the study. Groups and computerised (web-based) BA, IPT, and DYN were excluded for the following two reasons. First, our primary interest lies in the differences in CBT formats. Second, BA, DYN, and IPT have not been as extensively researched as CBT, making it difficult to compare interventions across various formats. Additionally, these three interventions conducted over the internet or in a group setting are less common than individual interventions for depression. For example, a meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of internet psychodynamic therapy (Lindegaard et al., Reference Lindegaard, Berg and Andersson2020) identified only one RCT targeting major depression. In a meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of internet BA (Alber et al., Reference Alber, Kramer, Rosar and Mueller-Weinitschke2023) only two RCTs met our criteria apart from the intervention. We identified one RCT on internet-delivered IPT (Donker et al., Reference Donker, Bennett, Bennett, Mackinnon, van Straten, Cuijpers, Christensen and Griffiths2013), but the participants were not diagnosed with depression. Furthermore, in a previous network meta-analysis (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Quero, Noma, Ciharova, Miguel, Karyotaki, Cipriani, Cristea and Furukawa2021) comparing various psychotherapies for depression, four studies on group-format BA were identified, none of which included participants diagnosed with depression. Additionally, the meta-analysis included three studies on group-format IPT, but these involved participants with perinatal depression or without a depression diagnosis. None of these studies met our inclusion criteria regarding participants’ characteristics. Moreover, no studies on group-format DYN were reported in the network meta-analysis. Therefore, comparing various formats of BA, DYN, and IPT individually is challenging. We also avoided grouping different formats within the same intervention group to prevent bias.

Information sources and search strategy

This study is registered in the PROSPERO database (PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021074566). We collected systematic reviews, network meta-analyses, and meta-analyses regarding the effects of psychotherapies for depression by searching MEDLINE using PubMed and the Cochrane Library. We searched them from the first date available to December 9, 2021. The searches were combined for depression, psychotherapy, and meta-analyses. The search strings for PubMed (MEDLINE) and the Cochrane Library were as follows: (“CBT” OR “cognitive behavioral therapy” OR “cognitive therapy” OR “CT” OR “behavioral therapy”) OR (“IPT” OR “interpersonal psychotherapy”) OR (“BA” OR “behavioral activation”) OR (“psychoanalysis” OR “psychoanalytic therapy” OR “psychodynamics” OR “psychodynamic therapy”) AND (“metanalysis” OR “meta-analysis” OR “systematic review”) AND (“depression” OR “MDD” OR “depressive”).

The studies identified through the databases were listed alphabetically by title; subsequently, we manually searched for duplicates in an Excel file and selected only the eligible studies. Systematic reviews (network/meta-analyses) on psychotherapies, including CBT, IPT, BA, or DYN, for depression among adults were included.

Next, we reviewed all RCTs included in the selected systematic reviews. Since these RCTs also encompassed studies found in PsycInfo, PsycArticles, and other databases, we believe that our search was comprehensive. We searched for systematic reviews, network meta-analyses, and meta-analyses up to December 2021; however, even the most recent meta-analyses included RCTs only up to the year 2020. Therefore, we conducted an additional search for RCTs not covered by these systematic reviews (network/meta-analyses) directly through MEDLINE and the Cochrane Library from January 1, 2020, to the date of the search, January 12, 2022. In the searches, we combined terms for depression and psychotherapy. The search strings for PubMed (MEDLINE) and the Cochrane Library were as follows: (“cognitive therapy” OR “cognitive behavioral therapy” OR “cognitive behavior therapy” OR “CBT” OR “interpersonal psychotherapy” OR “IPT” OR “behavioral activation” OR “behavior activation” OR “psychoanalysis” OR “psychodynamics”) AND depress*.

Finally, the RCTs obtained through the identified systematic reviews and databases were listed alphabetically by title. Subsequently, we manually searched for duplicates in an Excel file and selected only eligible studies.

Study selection

First, we reviewed the titles of all retrieved reports and selected the eligible ones. Next, we read the abstracts of the reports with eligible titles and selected the articles with eligible abstracts. Finally, we read the full texts of the reports with eligible abstracts and selected articles with eligible full texts. The lists of included and excluded reports are shown in the Supplementary Materials. The same process was followed when searching for RCTs and systematic reviews. Two reviewers, including the first author, independently selected the reports according to the eligibility criteria. One screened the reports, and the other checked the decisions. Disagreements were resolved through discussion between the reviewers.

Data collection

We included studies in which the treatment/observation period was between 6 and 24 weeks/sessions because depression can be efficaciously treated with 6 sessions of psychotherapy (Nieuwsma et al., Reference Nieuwsma, Trivedi, McDuffie, Kronish, Benjamin and Williams2012), and clinical guidelines generally recommend taking antidepressants for at least 6 months (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis and Smith2002; Lu et al., Reference Lu and Roughead2012; Malhi et al., Reference Malhi, Bell, Boyce, Mulder, Bassett, Hamilton, Morris, Bryant, Hazell, Hopwood, Lyndon, Porter, Singh and Murray2022). If the duration/sessions were longer than 24 weeks (6 months)/24 sessions, we used the last data between 6 weeks/6 sessions and 24 weeks/24 sessions as post-treatment data.

The TAU group included medication, clinical management, and other unstructured psychotherapies, such as supportive counselling, non-directive supportive psychotherapy, psychoeducation, relaxation, group self-help meetings, and group discussions. The forms of these treatments included face-to-face therapy and online sessions. Participants were categorised as having WLC if they had neither psychotherapy nor medication. However, if they had either psychotherapy or medication, they were categorised as having TAU. In this study, we focused on the treatment effects observed in actual clinical practice and aimed to investigate which psychotherapies were effective. Therefore, we excluded placebo, which is not used as a treatment in actual clinical practice, from the control group. We also examined the effects of a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. The psychotherapy group was categorised as a combination arm of psychotherapy and medication if more than 50% of the participants were using medication, regardless of the type of antidepressant used.

Depression severity was measured using common depression scales at baseline and end of the acute-phase treatment. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (6-, 17-, 21-, or 24-item HRSD) (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1960), Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and its self-report version (MADRS-S) (Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery and Asberg1979), Beck Depression Index (BDI) (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer, Ball and Ranieri1996), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001), Quick-/Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS or IDS) (Rush et al., Reference Rush, Trivedi, Ibrahim, Carmody, Arnow, Klein, Markowitz, Ninan, Kornstein, Manber, Thase, Kocsis and Keller2003), and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD) (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977) were accepted in our study. When multiple scales were used, the objective indicators (i.e. HRSD and MADRS) were used as the primary outcome measures, and when self-rating was used, the BDI, PHQ-9, MADRS-S, QIDS, or IDS- self-report (SR) and CESD were used in order of priority. If a significant difference was found between the arms in the baseline data of the primary outcome measure, the secondary outcome measure data were used if available.

The baseline severity of the participants was classified as mild, moderate, or severe according to the primary outcome at baseline. On the 17-item HRSD, scores of 8–13, 14–18, and ≥19 were classified as mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively. Regarding the 21-item HRSD, scores of 8–17 were classified as mild depression, 18–24 as moderate depression, and ≥25 as severe depression. On the 24-item HRSD, scores between 8 and 20 were classified as mild depression, 21 and 35 as moderate depression, and ≥36 as severe depression. Scores of 7–19, 20–34, and ≥35 were classified as mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively, on the MADRS. BDI scores of 14–20 were classified as mild depression, 21–30 as moderate depression, and ≥31 as severe depression. PHQ-9 scores of 5–9, 10–19, and ≥20 were classified as mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively. QIDS scores of 6–10 were classified as mild depression, 11–15 as moderate depression, and ≥16 as severe depression. On the IDS-SR30, scores of 14–25, 26–38, and≥39 were classified as mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively. CESD scores of 10–15 were classified as mild depression, 16–24 as moderate depression, and ≥25 as severe depression.

We collected (1) the author and publication year, (2) study design (i.e. intention-to-treat or per-protocol analysis), (3) intervention and comparator, (4) number of participants, (5) number of treatment sessions, (6) treatment duration, (7) combined use or non-use of medication, and (8) outcomes. The outcomes included the mean and standard deviation at baseline and post-treatment from the published article or supplementary material. If only the mean data were available on a graph, we measured the counts on the graph using a ruler and used it as the mean data. If there were any missing data, the corresponding author was asked to share the unpublished data directly via email. The collected data were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet. One reviewer extracted the necessary data, and the other checked the data.

Risk of bias

The Cochrane risk of bias (RoB) 2.0 tool was adopted to assess the risk of bias (ROB) in the following five domains: (1) bias arising from the randomisation process, (2) bias due to deviations from intended interventions, (3) bias due to missing outcome data, (4) bias in the measurement of the outcome, and (5) bias in the selection of the reported result. Subsequently, the overall bias was estimated. The five domains and overall bias were categorised as low, some, or high concern for each RCT and all RCTs, respectively. The estimate of all RCTs is presented in Supplementary Figure S1. In the figure green indicates low concern, yellow indicates some concern, and red indicates high concern.

Strategy for data synthesis

We used a random-effects model for data synthesis with the R package netmeta (R version 4. 2. 1). Since we accepted six different depression scales as outcome measures, the post-treatment outcomes were synthesised as the standardised mean difference (SMD), which is a common method in meta-analyses of treatment effects for depression (Murad et al., Reference Murad, Wang, Chu and Lin2019). To avoid correlation bias, the SMD was calculated as the mean and standard deviation of the post-treatment results, assuming that no difference was found in baseline results between the intervention and control groups in a quality-assured RCT.

We constructed a forest plot for each direct pairwise comparison and calculated the I2 statistics. If the I2 statistics range from 75% to 100%, heterogeneity may be observed in the comparison (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; chapter 10). Subsequently, we analysed the network meta-analysis for all comparisons, which are shown in the comparison matrix and forest plots. We evaluated the inconsistency using Separating Indirect from Direct Evidence, which measures the inconsistency between direct and indirect estimates for each comparison. If the p-value was <0.05, the presence of inconsistencies was determined (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; chapter 11).

To explore the heterogeneity, we conducted subgroup analyses according to the baseline severity of depression, depression scales, and low ROB. The subgroup analyses were conducted through network meta-analyses using pairwise comparisons, which are shown in the comparison matrix and forest plots.

Reporting bias assessment

Reporting bias was assessed using Egger’s test in a funnel plot. If p < 0.05, we considered the presence of publication bias (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; chapter 13).

Certainty

To evaluate the quality of the synthesised outcomes, we assessed the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) using Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis (CINeMA) to rate each pairwise comparison in the following six domains: (1) within-study bias, (2) reporting bias, (3) indirectness, (4) imprecision, (5) heterogeneity, and (6) incoherence. The confidence of the evidence is then classified as ‘high,’ ‘moderate,’ ‘low,’ and ‘very low.’ One reviewer evaluated the certainty, while another verified it. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion. The GRADE assessment for each pairwise comparison is detailed in Supplementary Figures S2 and S3, encompassing six domains and confidence ratings. The six domains are coded as follows: green for no concern, yellow for some concerns, and red for major concerns. The confidence ratings are coded as follows: green for high, blue for moderate, orange for low, and red for very low.

Results

Study selection

We identified 3,367 records through systematic review searches in the database and found 86 duplicates. We excluded 3,084 records based on the title, abstract, and an additional unretrievable report. Subsequently, we assessed 206 full texts, including 10 records identified from the references of eligible studies. We further retrieved 159 reports and excluded 47. Data from six reports were duplicates; therefore, we finally included 153 systematic reviews. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the search of systematic reviews is shown in Figure 1. The included and excluded reports with reasons for exclusion are listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram for the search of systematic reviews. PRISMA = preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

We identified 10,038 reports as follows: 5,072 reports from 153 systematic reviews and 4,966 reports from database searches. A total of 3,941 duplicates were identified. From the remaining 6,097 reports, we excluded 5,825 reports based on the title and abstract and an additional unretrievable report. We assessed the eligibility of 272 reports, including one identified from the references of an eligible study. A total of 116 reports were included, and 156 were excluded. Data from 27 of the 116 reports were duplicates; therefore, we included the remaining 89 unique studies. Among these studies, some conducted multiple RCTs, resulting in a total of 100 RCTs. Therefore, the reports comprised 116 publications, of which 89 were unique studies that included 100 RCTs. Figure 2 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the search of RCTs. The included and excluded reports with reasons for exclusion are listed in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4, respectively. The selected 100 RCTs included 9,873 participants.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram for the search of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). PRISMA = preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Characteristics of the studies

The characteristics of the included RCTs are described in Table 1. All participants were diagnosed with depressive disorders according to the DSM III/IV/5 or RDC. The baseline mean severity of depression among the participants was mild, moderate, and severe in 16, 48, and 36 RCTs, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of included trials

BA = behavioural activation, BDI = Beck Depression Index, CBT (ftf) = individual face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy, CESD = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, DYN = psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy, gCBT = group cognitive behavioural therapy, iCBT = computerised or Internet cognitive behavioural therapy, IPT = interpersonal psychotherapy, MADRS = Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, MADRS-S = a self-report version of MADRS, PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9, (Q)IDS / - SR = (Quick) Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology / Self-Report, RCTs = randomised controlled trials, ROB = the risk of bias, TAU = treatment-as-usual, WLC = wait list control, + p = + pharmacotherapy.

The most compared intervention arm was CBT (ftf) (65 treatment groups), of which 18 were CBT (ftf) plus pharmacotherapy (+ p). There were 14 gCBT treatment groups, of which gCBT + p comprised nine groups. There were 14 iCBT groups, of which seven were iCBT + p. There were 30 IPT groups, of which seven were IPT + p. There were seven DYN groups, of which three were DYN + p. The least compared group was BA (six treatment groups), of which BA + p comprised three groups.

To assess the efficacy of the treatments, the HRSD was the most used objective depression scale (n = 58), and the BDI was the most used self-rating scale (n = 67). Twenty-three RCTs had<10 sessions, 70 had ≥10 to ≤ 20 sessions, and 5 had>20 sessions. One included RCT did not report the number of sessions, but its treatment duration was 10 weeks; therefore, the number of sessions was approximately 10. The characteristics of each RCT are detailed in Supplementary Table S5.

Risk of bias in the included studies

More than half of the RCTs were judged to be at low risk in the following four ROB domains: arising from the randomisation process (87 RCTs), selection of the reported result (80 RCTs), missing outcome data (68 RCTs), and measurement of the outcome (56 RCTs). Most studies (94 RCTs) were judged to have some ROB due to deviations from the intended interventions, and six RCTs were at a high ROB in the domain. This was because of the nature of psychotherapy, in which both therapists and participants knew their assigned treatment groups. Therefore, we decided that this bias domain was not important for our study, which examined the efficacy of psychotherapy. The overall ROB was low for the RCTs, of which bias due to deviations from intended interventions was rated as ’some concerns,’ and all the other bias domains were rated as ‘low concerns’ (Supplementary Figure S1). Overall, 31 RCTs had a low ROB, five had some concern, and 64 had a high ROB. Among these high-risk RCTs, 19 RCTs had a high ROB because of a self-rating depression scale. The result of ROB for each RCT, including the mean and standard deviation at the post-treatment outcome, is shown in Supplementary Table S6.

Network plot

We conducted analyses using two groups. In group 1 (Grp1), we did not distinguish between psychotherapy alone and psychotherapy combined with medication, and the treatment arms were sorted into the psychotherapy groups, TAU, and WLC. In group 2 (Grp2), psychotherapy arms were sorted into psychotherapy alone and psychotherapy combined with medication separately. Therefore, we included 99 RCTs (9,849 participants) in Grp1. This was because, from Grp1, we further excluded one RCT (Stravynsk 1994), in which a comparison was made between two groups (gCBT and gCBT + p), whereas this RCT was included in Grp2.

Network plots for Grp1 and Grp2 are shown in Figure 3a and b, respectively. The nodes and edges were weighted according to the number of direct comparisons. In Grp1, the treatment arms were well compared. All treatment arms were compared with TAU. CBT (ftf) was compared with all other psychotherapies except for gCBT. In Grp2, the treatment arms were well inter-compared, except for DYN + p, which was directly compared only with TAU. All treatment arms were compared with TAU. Psychotherapy alone was frequently compared with other psychotherapy-alone groups, while psychotherapy combined with medication was often compared with other combination therapy groups. The CBT (ftf) alone group and the CBT (ftf) + p group were compared more frequently than other treatment groups. CBT (ftf) alone was directly compared to DYN, iCBT, IPT, and BA, whereas CBT (ftf) + p was directly compared to iCBT + p, IPT + p, and BA + p. Direct comparisons were also conducted between psychotherapy alone and the same psychotherapy combined with medication (i.e. CBT (ftf) vs. CBT (ftf) + p, gCBT vs. gCBT + p, and IPT vs. IPT + p).

Figure 3. Network plot. Grp1 and Grp2 are shown in (a) and (b), respectively. The nodes represent the number of groups, while the edges represent direct comparisons, with the thickness of the edges proportional to the number of comparisons. Grp1 = Group 1: psychotherapy arms were not distinguished between psychotherapy alone and psychotherapy combined with medication. Grp2 = Group 2: psychotherapy arms were sorted into psychotherapy alone and psychotherapy combined with medication. BA = behavioural activation, CBT (ftf) = individual face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy, DYN = psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy, gCBT = group cognitive behavioural therapy, iCBT = computerised or Internet cognitive behavioural therapy, IPT = interpersonal psychotherapy, TAU = treatment-as-usual, WLC = wait list control, + p = + pharmacotherapy.

Pairwise meta-analyses and inconsistency

All direct comparisons with I2 statistics and the difference between direct and indirect treatment estimates for Grp1 and Grp2 are respectively presented in Supplementary Tables S7 and S8. In Grp1, considerable heterogeneity may exist in ‘BA versus TAU (I2 = 76.3%),’ ‘gCBT versus TAU (I2 = 90.5%),’ and ‘iCBT versus TAU (I2 = 87.3%).’ However, as indicated by the forest plots of these comparisons, the treatment effects in the RCTs were consistent and unidirectional in each comparison (Supplementary Figure S4a–c). Similarly, considerable heterogeneity may exist in ‘gCBT + p versus TAU (I2 = 92.1%)’ and ‘iCBT versus TAU (I2 = 93.4%)’ in Grp2. However, the forest plots of these comparisons reveal consistent and unidirectional treatment effects in each of the RCTs (Supplementary Figure S5a and b). In ‘CBT (ftf) versus CBT (ftf)+p (I2 = 78.3%),’ the forest plot showed that one study exhibited an outlier; however, as its confidence interval (CI) overlapped with those of other studies, we deemed it appropriate to conduct a network meta-analysis and subsequently performed subgroup analyses (Supplementary Figure S5c).

In Grp1, inconsistencies were observed in the comparisons between CBT (ftf) and iCBT (p = 0.0192), CBT (ftf) and TAU (p = 0.0091), and gCBT and WLC (p = 0.0310). However, the above-mentioned comparisons did not exhibit inconsistency in Grp2. Therefore, the inconsistency in the above-mentioned comparisons in Grp1 may be attributed to a wide-ranging participant pool, which included participants receiving and not receiving pharmacotherapy. In Grp2, inconsistencies were noted in BA + p versus CBT (ftf) + p (p = 0.0461) and BA + p versus TAU (p = 0.0303). These comparisons had data from only two RCTs for direct comparison, potentially introducing bias in data collection. Therefore, we downgraded the GRADE evaluation for these two comparisons.

Network meta-analysis

We conducted a network meta-analysis, presented as comparison matrices in Tables 2 and 3, for Grp1 and Grp2, respectively. Significant results are highlighted in bold in these tables. In Grp1, the SMDs of BA, CBT (ftf), gCBT, and iCBT compared to TAU were as follows: BA: (SMD = −0.4238, 95% CI = [–0.7649; –0.0826]), CBT (ftf): (–0.1719 [–0.2931; –0.0507]), gCBT: (–0.7294 [–1.0021; –0.4567]), and iCBT: (–0.7075 [–0.9283; –0.4868]). These results indicate that BA, CBT (ftf), gCBT, and iCBT were significantly more effective than TAU, as shown in the forest plot against TAU (Figure 4a). The other treatment groups (DYN and IPT) were not inferior to TAU. gCBT was significantly more effective than CBT (ftf): (0.5575 [0.2605; 0.8545]), DYN: (0.6284 [0.2108; 1.0459]), and IPT: (0.6979 [0.3723; 1.0235]). Similarly, iCBT was significantly more effective than CBT (ftf) (0.5356 [0.2938; 0.7774]), DYN: (0.6064 [0.2227; 0.9901]), and IPT: (0.6760 [0.3963; 0.9557]) (Table 2).

Figure 4. Forest plot of comparisons against TAU. Grp1 is shown in (a), and Grp2 is shown in (b). A horizontal line represents a 95% confidence interval (95% CI), and a point on the line represents the standardised mean difference (SMD) in a pairwise comparison between a treatment and TAU in network meta-analysis. The bottom scale represents SMD. SMD <0 means that a treatment can be more effective than TAU. If the 95% CI does not cover 0, the estimate is statistically significant.Grp1 = Group 1: psychotherapy arms were not distinguished between psychotherapy alone and psychotherapy combined with medication. Grp2 = Group 2: psychotherapy arms were sorted into psychotherapy alone and psychotherapy combined with medication. BA = behavioural activation, CBT (ftf) = individual face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy, DYN = psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy, gCBT = group cognitive behavioural therapy, iCBT = computerised or Internet cognitive behavioural therapy, IPT = interpersonal psychotherapy, TAU = treatment-as-usual, WLC = wait list control, + p = + pharmacotherapy.

Table 2. Comparison matrix for main results in Grp1

*= standardised mean difference (SMD), ** = 95% confidence interval (95%CI), Left-bottom values are network results, and right-upper values are direct estimates. In the network results, SMD >0 indicates that the row-defining intervention is more efficacious than the column-defining intervention. If the confidence interval does not cover 0, the estimate is statistically significant. Statistically significant differences are indicated in bold. BA = behavioural activation, CBT (ftf) = individual face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy, DYN = psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy, gCBT = group cognitive behavioural therapy, iCBT = computerised or Internet cognitive behavioural therapy, IPT = interpersonal psychotherapy, TAU = treatment-as-usual, WLC = wait list control, Grp1: a group 1, in which we did not distinguish between psychotherapy alone and combination with medication, and treatment arms were sorted into psychotherapy groups, TAU, and WLC.

Table 3. Comparison matrix for main results in Grp2

*= standardised mean difference (SMD), ** = 95% confidence interval (95%CI), Left-bottom values are network results, and right-upper values are direct estimates. In the network results, SMD >0 indicates that the row-defining intervention is more efficacious than the column-defining intervention. If the confidence interval does not cover 0, the estimate is statistically significant. Statistically significant differences are indicated in bold. BA = behavioural activation, CBT (ftf) = individual face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy, DYN = psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy, gCBT = group cognitive behavioural therapy, iCBT = computerised or Internet cognitive behavioural therapy, IPT = interpersonal psychotherapy, TAU = treatment-as-usual, WLC = wait list control, + p = + pharmacotherapy, Grp2: a group 2, in which psychotherapy arms were sorted into a psychotherapy alone and a psychotherapy combined with medication separately.

In Grp2, as indicated by the forest plot against TAU (Figure 4b), BA + p: (–0.7779 [–1.2356; –0.3203]), CBT (ftf) + p: (–0.4770 [–0.6652; –0.2888]), gCBT + p: (–1.0330 [–1.3387; –0.7273]), iCBT: (–0.5147 [–0.8129; –0.2164]), and iCBT + p: (−0.7893 [−1.0916; −0.4870]) were significantly more effective than TAU. The other treatment groups were not inferior to TAU.

Most psychotherapies combined with medication were significantly more effective than the same psychotherapy alone; that is, BA + p was more effective than BA: (0.6540 [0.0023; 1.3057]), CBT (ftf) + p was more effective than CBT (ftf): (0.4761 [0.2589; 0.6934]), gCBT + p was more effective than gCBT: (1.0463 [0.5452; 1.5474]), and IPT + p was more effective than IPT: (0.3860 [0.0666; 0.7055]). Many psychotherapies combined with medication showed more significant treatment effects than some other types of psychotherapy alone; for example, BA + p was more effective than CBT (ftf): (0.7771 [0.3043; 1.2499]), DYN: (0.9627 [0.3390; 1.5864]), gCBT: (0.7913 [0.1596; 1.4229]), and IPT: (0.8904 [0.3994; 1.3815]). Notably, gCBT + p and iCBT + p were more effective than any other psychotherapy alone (Table 3).

Moreover, gCBT + p was significantly more effective than other combined therapies, such as CBT (ftf) + p (0.5560 [0.1971; 0.9150]), DYN + p (0.7497 [0.2233; 1.2761]), or IPT + p (0.7595 [0.3343; 1.1846]). Surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA) indicates the estimated ranking for each treatment (Supplementary Figures S6 and S7). Consequently, the results indicated that gCBT had the highest therapeutic effect in Grp1, whereas in Grp2, gCBT + p was found to be the most effective treatment.

The main results suggested that (1) no treatment group was inferior to TAU, (2) psychotherapy combined with medication was more effective than psychotherapy alone, and (3) gCBT + p was the best combination of psychotherapy and medication.

Subgroup analyses

To minimise heterogeneity, we implemented restrictive inclusion criteria. However, heterogeneity cannot be completely avoided. To explore the heterogeneity, we conducted subgroup analyses based on the baseline severity of depression, depression scales, and ROB, which may partly contribute to the factors of heterogeneity and inconsistency. The comparison matrices for subgroup analyses are shown in Supplementary Tables S9–14 for Grp1 and S15–20 for Grp2. Significant results are highlighted in bold in the table.

In Grp1, as indicated by the forest plot against TAU (Supplementary Figure S8a-c) among patients with any severity of depression at baseline, gCBT was superior to TAU. The SMD and 95% CI for each subgroup were –0.6960 [–1.2129; –0.1791]; –0.3407 [–0.6371; –0.0443]; and –3.5669 [–4.3115; –2.8223] among patients with mild, moderate, and severe depression at baseline, respectively. Other treatment groups were occasionally superior to, but never inferior to, the TAU group.

Similar results were obtained in subgroup analyses of RCTs using observer-rated depression scales (i.e. HRSD), self-rated depression scales (i.e. BDI), and trials with low ROB (Supplementary Figure S9a-c).

In Grp2, as demonstrated in the forest plot comparing to TAU (Supplementary Figure S10a-c), regardless of baseline depression severity, gCBT + p was more effective than TAU. The SMD and 95% CI for the comparison between gCBT + p and TAU for each severity level are as follows.: mild depression (–0.6961 [–1.2472; –0.1451]), moderate depression: (–0.5607 [–0.9584; –0.1630]), and severe depression: (–3.5449 [–4.2342; –2.8557]). Among patients with mild depression, the treatment effect of the other therapies was non-inferior to TAU. In contrast, among patients with moderate-to-severe depression, some psychotherapies combined with medication were more effective than TAU. Additionally, as shown in the forest plots against gCBT + p (Supplementary Figure 11a and b), for patients with moderate-to-severe depression, gCBT + p was more effective than many other groups. This implies that it was more effective than CBT (ftf): (0.5500 [0.1134; 0.9866]) and IPT: (0.7396 [0.2593; 1.2199])among patients with moderate depression (Supplementary Figure S11a), and more effective than BA (3.3453, [2.4015; 4.2890]), BA + p (2.4866, [1.6546; 3.3187]), CBT (ftf) (3.6550 [2.9491; 4.3608]), CBT (ftf) + p (2.9676 [2.2505; 3.6847]), DYN (3.7417 [2.9751; 4.5082]), DYN + p (3.2491 [2.5033; 3.9949]), iCBT (3.6046 [2.7625; 4.4467]), iCBT + p (3.1938 [2.2639; 4.1237]), IPT (3.6259 [2.9031; 4.3488]), and IPT + p (3.3417 [2.5546; 4.1288]) among those with severe depression (Supplementary Figure S11b). No significant difference was found in the treatment efficacy between psychotherapy combined with medication and psychotherapy alone among patients with mild depression (Supplementary Table S15). However, for patients with moderate-to-severe depression, many psychotherapies combined with medication were more effective than psychotherapy alone (Supplementary Tables S16 and S17). When compared to CBT (ftf) as indicated by the forest plot against it, for instance, gCBT + p (-0.5500 [−0.9866; –0.1134]), iCBT (–0.6388 [–1.0339; –0.2437]), and iCBT + p (–1.0723 [–1.4773; –0.6672]) were superior for treating moderate depression (Supplementary Figure S12a). For severe depression, BA + p (–1.1683 [–1.6561; –0.6806]), CBT (ftf) + p (–0.6874 [–0.9226; –0.4521]), DYN + p (–0.4059 [–0.7289; –0.0829]), gCBT (–3.0536 [–4.1843; –1.9229]), and gCBT + p (–3.6550 [–4.3608; –2.9491]) were more effective than CBT (ftf) (Supplementary Figure S12b).

The subgroup analyses using HRSD or BDI as depression scales yielded comparable results to those of the subgroup analyses conducted among patients with moderate-to-severe depression. As illustrated in each corresponding forest plot, gCBT + p demonstrated superior efficacy compared to TAU and surpassed the efficacy of all psychotherapies alone (Supplementary Figure S13a and b). Many psychotherapies combined with medication were more effective than both TAU (as shown in Supplementary Figure S14a and b), and psychotherapies alone, as shown in the comparison with CBT (ftf) (Supplementary Figure S15a and b).

In the subgroup analysis for RCTs with a low ROB, gCBT + p yielded higher efficacy than TAU, all psychotherapies alone, and psychotherapies combined with medication other than iCBT + p (Supplementary Figure S16).

The results of the subgroup analyses implied that (1) gCBT + p was the best combination of psychotherapy and medication; (2) no treatment group was inferior to TAU, which included pharmacotherapy; (3) many psychotherapies combined with medication were significantly more effective than TAU; (4) among patients with mild depression, no significant difference was found in treatment efficacy between any psychotherapy combined with medication and psychotherapy alone; and (5) among patients with moderate-to-severe depression, most psychotherapies combined with medications were more effective than psychotherapy alone.

Grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluations

As shown in the funnel plot with Egger’s test for each comparison in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Figures S17 and S18), publication biases were found in the direct pairwise comparisons of ‘CBT (ftf) versus IPT’ (Egger’s test: p = 0.016) and ‘iCBT versus TAU’ (p = 0.004) in Grp1, and ‘CBT (ftf) versus IPT’ (p = 0.009), ‘iCBT + p versus TAU’ (p = 0.016) and ‘IPT + p versus TAU’ (p = 0.005) in Grp2. Notably, no publication bias was found in the comparison of ‘gCBT versus TAU’ in Grp1 and ‘gCBT + p versus TAU’ in Grp2.

For other direct pairwise comparisons (Egger’s test: p ≥ 0.05) and indirect comparisons, we were not concerned about the reporting bias domain because we performed an exhaustive search of eligible RCTs and used unpublished data, requesting that the corresponding authors share it. No indirectness in population, intervention, or outcome was found because all included RCTs had similar participants (patients with depressive disorder diagnosed according to the diagnostic criteria), intervention (limited duration/sessions), and outcome measures (five depression rating scales at baseline and post-treatment).

The GRADE results are shown in Supplementary Figures S2 and S3 in Grp1 and Grp2 respectively. In Grp 1, no comparisons had high confidence, 22 had moderate confidence, and six, including gCBT vs. TAU, had low confidence. In Grp2, ‘gCBT + p versus TAU,’ ‘gCBT + p versus BA,’ ‘gCBT + p versus CBT (ftf),’ ‘gCBT + p versus DYN,’ ‘gCBT + p versus IPT,’ ‘BA + p versus DYN,’ ‘BA + p versus IPT,’ ‘CBT (ftf) + p versus WLC,’ ‘iCBT + p versus CBT (ftf),’ ‘iCBT + p versus DYN,’ and ‘iCBT + p v versus IPT’ had high confidence. ‘BA + p versus CBT (ftf) + p,’ BA + p versus TAU,’ ‘CBT (ftf) versus IPT,’ ‘CBT (ftf) versus TAU,’ and ‘IPT + p versus TAU’ had low confidence. Other comparisons, including gCBT and TAU, showed a moderate level of confidence. No comparisons had very low confidence in the GRADE for either Grp1 or 2. From the GRADE results, we confidently concluded that gCBT + p was the most effective treatment for adults with depression within the inclusion criteria.

Discussion

In this network meta-analysis, we evaluated the relative effectiveness of common psychological therapies, encompassing various delivery formats of CBT and their combined use with medication in patients diagnosed with depressive disorder. Our results suggest that psychotherapies, when combined with medications, generally outperform psychotherapy alone or standard TAU, including pharmacotherapy alone. Notably, the combination of gCBT and medication emerged as a particularly effective strategy for treating adult depression.

Corroborating our findings, previous studies and established guidelines suggest that a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy provides enhanced benefits compared to each treatment alone. Its effectiveness can be attributed to improved medication adherence (Gaspar et al., Reference Gaspar, Zaidel and Dewa2019; González de León et al., Reference González de León, del Pino-Sedeño, Serrano-Pérez, Rodríguez Álvarez, Bejarano-Quisoboni and Trujillo-Martín2022; Forma et al., Reference Forma, Liberman, Rui and Ruetsch2023) and the distinct mechanisms of action of each treatment (Sankar et al., Reference Sankar and Fu2015; Lemmens et al., Reference Lemmens, Müller, Arntz and Huibers2016; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Zamparelli, Nettis and Pariante2021).

A previous study further suggested that group psychotherapy usually yields better outcomes than an individual format (Neimeyer et al., Reference Neimeyer, Robinson, Berman and Haykal1989). Group psychotherapy has multiple benefits as follows: it allows participants to gain insights from peers with similar struggles, provides mutual support, fosters behavioural changes through the recovery process of other members, and treats a greater number of people at a time than individual therapy, thereby reducing the waiting period (Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn and Clarke1999; Yalom et al., Reference Yalom and Leszcz2005; Whitfield, Reference Whitfield2018). Moreover, group interventions are more cost-effective than individual sessions in treating depression (Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, Sank, Shaffer and Donovan1982; Tucker et al., Reference Tucker and Oei2007).

Nevertheless, some previous reports comparing individual and group CBT concluded that no significant differences were found between the formats (Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, Sank, Shaffer and Donovan1982; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt and Miller1983; Ross et al., Reference Ross and Scott1985; Teri et al., Reference Teri and Lewinsohn1986; Scott et al., Reference Scott and Stradling1990; Zettle et al., Reference Zettle, Haflich and Reynolds1992), contrasting with our findings. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that these studies did not exclusively focus on patients diagnosed with depression (Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, Sank, Shaffer and Donovan1982; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt and Miller1983; Ross et al., Reference Ross and Scott1985; Teri et al., Reference Teri and Lewinsohn1986) and were not RCTs (Scott et al., Reference Scott and Stradling1990; Zettle et al., Reference Zettle, Haflich and Reynolds1992). Therefore, we did not include these studies that do not meet the inclusion criteria in our research.

Furthermore, a previous study reported that individual psychotherapy was slightly more effective than group one during the acute phase of depression treatment (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, van Straten and Warmerdam2008). However, as the above-mentioned research stated, only a limited number of studies were included, and the overall quality of these studies was suboptimal. Additionally, the analysis did not differentiate between the types of interventions, such as CBT, BA, IPT, and DYN, but rather focused solely on individual versus group formats. Moreover, the participants in the above-mentioned study trials encompassed a broader range, including patients with depression in prisons, those with subthreshold depression, and those with postpartum depression, which differed from the participants in our study. These disparities in intervention categorisation and participant criteria likely contributed to discrepancies with our findings.

Another study suggested that individuals with a sociable disposition might derive greater benefits from group therapy, whereas those who are more self-regulating may find individual therapy more advantageous (Zettle et al., Reference Zettle, Haflich and Reynolds1992). Considering these factors, it is evident that the most suitable format, individual or group, might be influenced by both the personal characteristics of the patients and the specific type of therapy.

We also conducted subgroup analyses that categorised patients based on baseline depression severity and yielded results that differed from those of the overall study population. For patients with milder severity, no significant differences were found in effectiveness between psychotherapy combined with pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy alone, between all psychotherapies, and between each psychotherapy and TAU, except for gCBT + p showing higher treatment efficacy than TAU. In contrast, for patients with moderate-to-severe depression, most psychotherapies combined with pharmacotherapy were superior to psychotherapy alone or TAU.

The NICE and APA guidelines recommend treatment for depression according to its severity. For example, the NICE guidelines recommend only psychotherapy rather than regular administration of antidepressants for mild depression (NICE, 2022). Furthermore, for moderate-to-severe depression, both guidelines recommend psychotherapy combined with pharmacotherapy (APA 2019; NICE, 2022).While a previous study has shown that the therapeutic effects of antidepressants were not significantly different from those of a placebo in patients with mild depression (Kirsch et al., Reference Kirsch, Deacon, Huedo-Medina, Scoboria, Moore and Johnson2008), another report has demonstrated the effectiveness of second-generation antidepressants compared to placebo in this patient cohort (Furukawa et al., Reference Furukawa, Maruo, Noma, Tanaka, Imai, Shinohara, Ikeda, Yamawaki, Levine, Goldberg, Leucht and Cipriani2018). The APA guidelines also recommends selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors as first-line treatments for mild depression (APA 2019). Regarding quality of life, psychotherapy is reportedly more effective than pharmacotherapy (Kamenov et al., Reference Kamenov, Twomey, Cabello, Prina and Ayuso-Mateos2017). Furthermore, patients with depression tend to prefer psychological therapy to pharmacotherapy (McHugh et al., Reference McHugh, Whitton, Peckham, Welge and Otto2013). Therefore, discussing treatment options with patients and tailoring them according to their clinical needs and preferences is crucial.

A recent study has reported that psychotherapies were significantly superior to TAU in patients with depression (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Quero, Noma, Ciharova, Miguel, Karyotaki, Cipriani, Cristea and Furukawa2021). However, their analyses included studies of participants with other psychiatric comorbidities or medical conditions (e.g. coronary diseases, cancers, and brain injury) or specified backgrounds (e.g. caregivers, migrants, veterans, war victims, and perinatal women). In these participants, the treatment of comorbidities and the management of patients’ surrounding settings are expected to concurrently lead to the improvement of depressive symptoms rather than focusing solely on the treatment of depression. Therefore, we decided to center our comparison on adult patients formally diagnosed with depression, excluding those with specific comorbidities and backgrounds. As a result, in patients formally diagnosed with depression, the treatment efficacy between psychotherapy alone and TAU was not significantly different.

In a subgroup analysis of low-risk-biased RCTs, no significant difference was found in the efficacy between psychotherapy alone and combined therapy other than gCBT +p. The sample size for the subgroup was relatively small (31 RCTs, N = 3,484), which appeared to result in a different result from that of the main study.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, we categorised an intervention as psychotherapy alone, even if less than 50% of the allocated participants also used medication. The number of participants with mild baseline depression was lower than that of those with moderate or severe depression. The sample size was large in the CBT (ftf)-alone and TAU arms but small in the BA and DYN arms. Additionally, some subgroup analyses did not include certain types of interventions. These variations in the baseline characteristics may have affected the results. Second, because of the nature of psychotherapy, in which both therapists and participants knew the treatment group, ‘bias due to deviation from the intended intervention’ was deemed unimportant in this study of psychotherapy effectiveness. Therefore, in terms of the overall ROB, we ignored the bias due to deviation from the intended intervention when the bias domain was ’some concerns.’ Third, we could not avoid variations in the number of sessions, duration of intervention, and technique of the therapists, even if we limited the range of the number of sessions and duration as well as the types of intervention. Normally, DYN requires more than 1-year treatment duration (Khademi et al., Reference Khademi, Hajiahmadi and Faramarzi2019), and long-term effects may be different. Fourth, the effects of TAU may vary, as we categorised many treatments in the TAU group, such as counselling, discussion, psychoeducation, supportive therapy, relaxation therapy, and pharmacotherapy. Fifth, we compared only individual face-to-face BA, IPT, DYN, and several formats for CBT.

Therefore, conducting a future study is necessary to compare the treatment efficacy of several types of psychotherapy in several forms. In the respective analyses, participants with similar features, for example, depression severity, age, comorbidity, and background, should be collected. Furthermore, the efficacy of treatment should be observed both in the short- and long-term.

Conclusion

Among adults with formally diagnosed depression, the efficacies of psychotherapy alone and TAU, which includes pharmacotherapy, were not significantly different. For mild depression, the efficacies of psychotherapy combined with medication and psychotherapy alone were not significantly different. However, for moderate-to-severe depression, psychotherapy combined with medication was more effective than psychotherapy alone. Among these therapies, group CBT combined with medication demonstrated particularly good efficacy. Future research should focus on comparing different types of psychotherapy in various forms. Standardising participant characteristics and evaluating both short- and long-term treatment effects will be crucial for advancing our understanding of effective depression treatments.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2024.45.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

MF, T. Kudo, and T. Kikuchi conceived and designed the study. MF and T. Kikuchi collected the data. YZ and SH developed the statistical analysis plan, and YZ conducted the statistical analysis. MF and T. Kikuchi interpreted the data. MF drafted the original manuscript. T. Kudo and T. Kikuchi supervised the study. All authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (grant number JPMJCR19A5) through the CREST programme.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Non-applicable.