Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of invited contributors and not necessarily those of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries. The Institute and Faculty of Actuaries do not endorse any of the views stated, nor any claims or representations made in this publication and accept no responsibility or liability to any person for loss or damage suffered as a consequence of their placing reliance upon any view, claim or representation made in this publication. The information and expressions of opinion contained in this publication are not intended to be a comprehensive study, nor to provide actuarial advice or advice of any nature and should not be treated as a substitute for specific advice concerning individual situations. Not all the material in this paper necessarily reflects the views of all of the authors. Unpaid volunteers have produced this publication to promote discussion in the public interest. You are free to redistribute it or quote from it (with acknowledgement) without further permission or payment but you should quote from the work accurately and in context.

Introduction

This report, and the working party that has produced it, arose from a specific concern that, by quoting “1 in 200” numbers for capital requirements under Solvency II, actuaries were, perhaps unwittingly, being party to giving false confidence about the financial strength of insurers.

This issue naturally led on to broader reflections on uncertainty, looking beyond the actuarial profession and even beyond the insurance industry.

There is a tendency, amongst advisors/experts, and also most decision makers, to want to impose certainty on very uncertain situations. Actuaries, for example, may be called on to quantify, or assume away, problems by setting (fixed) assumptions about how the future could evolve. This can be at the expense of rigorous consideration of factors that are not readily quantifiable or, indeed, in any way knowable.

The failure to face up to issues surrounding uncertainty is a threat to good decision making, with issues arising in a number of areas:

-

The scope and nature of analysis undertaken by experts (such as actuaries); are important questions ignored because they are “too uncertain”?

-

The positioning and communication of such analysis and advice; is the fact that some difficult questions are out of scope highlighted? If uncertainties were highlighted, that might lead to the issues being thought about more.

-

The understanding of experts and their work by decision makers; “we paid for the advice, so let’s use it without worrying further”.

-

The intelligent recognition of uncertainty when decisions are made.

So how can uncertainty be managed to make better decisions?

This report is aimed at both decision makers and their advisors. While the context for much of the thinking of members of the working party is insurance, the ideas discussed are relevant to decision making across industries and government. Consideration is given to both technical and social aspects with an emphasis on being practical and constructive. A collection of anecdotes regaling past uncertainty calamities may be interesting but would not, in itself, offer support to decision makers often facing difficult circumstances and unenviable challenges.

The report is in two parts. The first part introduces six high level Uncertainty Principles for use in supporting, making and critiquing decisions:

-

Face up to uncertainty

-

Deconstruct the problem

-

Don’t be fooled (un/intentional biases)

-

Models can be helpful, but also dangerous

-

Think about adaptability and resilience

-

Bring people with you

The intention is for these to be both catchy and memorable, while being immediately meaningful and useful. They are offered as an overarching framework for further research and guidance. A summary explanation is provided for each principle followed by more in depth discussion including illustration through a number of uncertainty “vignettes”.

The second part explores three insurance-related case studies, highlighting situations where there is a high level of “unknowability”. The intention is to show how uncertainty is often handled, to illustrate some challenges to professionalism and the realities of improving decision making through applying the principles:

-

Managing uncertainty after being catastrophically wrong. An insurer facing key decisions following the 2017 catastrophe losses

-

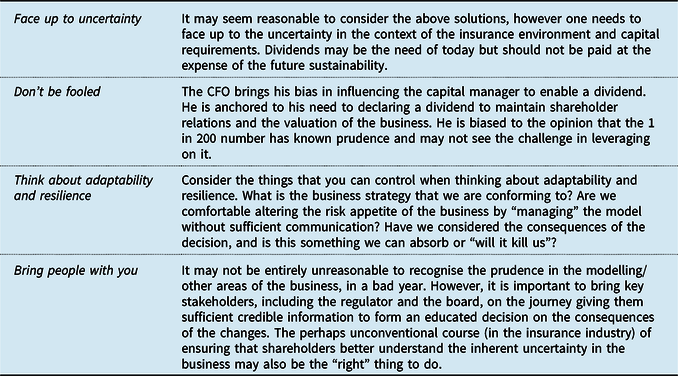

The dividend question. An insurer exploring options to reduce solvency capital requirements in order to free up capital to meet shareholders’ steady dividend expectations

-

I disagree! Exploring strategies an advisor might consider when responding to a valuation request, with various professionalism challenges to navigate

Part 1: Uncertainty Principles

1) Face up to Uncertainty

When making decisions, we are often confronted by uncertainty: the inherent unpredictability in future outcomes; a lack of information about the dynamics of the problem at hand; often compounded by the unknown, or unknowable.

Yet people crave certainty in what is a highly uncertain world. In practice, there is a tendency for people to downplay or ignore uncertainty when deciding on a course of action. Or, more dangerously, there is a tendency to impose certainty on a situation where there is little or none.

So, why focus on uncertainty when it is only the combination of luck and time that will tell if a particular course of action is the “better” one? We believe a “better” decision is one that is made with everyone’s eyes open – so that there is a more realistic and informed view of the degree of uncertainty in any situation, the potential impacts (where known) of these uncertainties crystallising and any mitigating actions (taken or not taken) to manage uncertainty within acceptable levels.

Facing up to uncertainty leads to more informed and better decision making. To help do this, we offer guidance through five further principles:

-

Deconstruct the problem

-

Don’t be fooled (un/intentional biases)

-

Models can be helpful, but also dangerous

-

Think about adaptability and resilience

-

Bring people with you

There is no single neat answer, but these principles offer practical and constructive ideas to help decision making in the face of uncertainty. Where uncertainty cannot be mitigated, the use of the principles will help ensure decisions are made with your eyes wide open and the eyes of others.

Facing up to uncertainty is at the heart of this paper. The aim of this principle is to encourage us all to “tune in” to uncertainty, with all its messiness and unpredictability, and in spite of our deeper instincts to turn away.

In order to be able to face up to uncertainty, you need to be confident that you have a strategy to deal with it. For this reason, in this section focusing on the first of our six principles, we introduce the other five before going on to discuss each of them. We would regard the first and the last of our principles: “face up to uncertainty” and “take people with you” as the most important of the six.

A degree of uncertainty is present in any decision. As is detailed in the Deconstruct the problem section, uncertainty can take a number of forms: inherent randomness, lack of knowledge, modelling limitations, ambiguity, errors, people factors and broader social and ethical factors. It is important to appreciate that where there is uncertainty there may be opportunity, just as much as there are risks.

Recent history shows us that uncertainty is a game with high stakes, and that the costs on society of failing to “face up to” and better manage uncertainty are high.

Examples include:

-

The global financial crisis of 2007–2008: in the 10 years up to 2006 US banks had delivered average returns of over 13% RoE; and yet, despite ever more sophisticated approaches to managing financial risks (including use of experts and financial models), the complexity within the system had obscured underlying exposures to loan defaults. See inset (Katzenstein, Reference Katzenstein2014)

-

Climate change: where global efforts to slow increasing temperatures and reduce the build up of greenhouse gases have not yet been successful – and uncertainty over the causes and effects of global warming has created a vacuum in which the risks and potential effects can be downplayed or denied

-

Nokia and Kodak: companies which, in the face of rapidly evolving technology, went from market leaders to potential insolvency in a short period of time

-

Deepwater Horizon in 2010: a disaster involving the loss of 11 lives and large complex pollution claims, with decision making (before and during) challenged by the inherent uncertainty of deep water drilling

-

The near collapse of Lloyd’s of London in the late 1980s/early 1990s: unmanageable exposure complexity (exacerbated by the “Excess of Loss Spiral”) combined with under anticipated losses (catastrophic events such as Piper Alpha and longer term asbestos and pollution claims)

Case study: Financial Crisis of 2007–2008: The near collapse of the American financial system in 2008 wiped out more than $11 trillion in household wealth. The peak-to-trough decline in real GDP was 4¼% and the decline in payroll employment even larger at 6.3%. The global financial crisis is considered by many economists to have been the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression and reshaped the world of finance and investment banking. In hindsight, it is clear the crisis had multiple causes but that at its root was a systematic failure to “face up to” the uncertainties inherent within the financial system and failure to build resilience into the system to protect against these.

The years before the crisis saw a flood of lending to “subprime” borrowers with poor credit histories, who subsequently defaulted on their loans, creating unprecedented defaults across the wider US and global economy. Financial institutions had become highly leveraged, reducing their resilience to losses of this scale. Much of the leverage was achieved using complex financial instruments such as off-balance sheet securitisation and derivatives, particularly credit default obligations (CDOs), which acted to repackage loans and pass risk on to third parties. Additional complexity had made it difficult to monitor and reduce financial risk at an institution and industry wide level.

“Elegant” (sic) financial models used to price CDOs were found to have been based on historic data from periods of low credit risk, as well as highly material and sensitive assumptions about the relationships between different credit risks. In the financial industry and academia, whilst a few had realised that the assumptions underlying these models were unrealistic, they were unsuccessful in highlighting the risks to those who could act. Warning signs were in general disregarded by industry practitioners who were enjoying profitable returns, and who wanted to retain market access. Regulators and rating agencies bore some responsibility too, for failing to keep economic imbalances in check and for failing to exercise proper oversight of financial institutions.

Focusing on human behaviours around uncertainty helps us understand how intelligent people, in an environment of copious information and complex analysis, adhered to social conventions that led them to believe that they were making decisions in a world of risk, when, in reality, those very conventions led them to the cliff’s edge.

Sources:

-

[1] https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d6a2/26e54cff14f38df986f09773b063629602a5.pdf

-

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Financial_crisis_of_2007%E2%80%932008

-

[3] https://media.economist.com/sites/default/files/pdfs/store/Managing_Uncertainty.pdf

-

[4] http://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/~scn407/documents/NelsonandKatzensteinIOApril2014.pdf

-

[5] https://www.princeton.edu/ceps/workingpapers/243blinder.pdf

-

[6] https://mitsloan.mit.edu/LearningEdge/CaseDocs/09-093%20The%20Financial%20Crisis%20of%202008.Rev.pdf

There are many examples where uncertainty is managed well, albeit such cases naturally attract less attention. These underpin the thinking behind the proposed principles, which are highlighted throughout the paper.

It is worth noting that uncertainty is present as much on a personal, as a corporate or national level. You may have grappled with the decisions involved with buying a house and experienced how hard it is to do so without a full understanding of your current and future requirements, the motivations of the seller or having all of the facts to hand. The potential for financial (and emotional) gain can be significant and so is the potential for loss. Whilst additional research (e.g. a surveyor, talking with neighbours, preparing an analysis) might reduce some of the uncertainty, it will not remove it completely, nor will it always bring uncertainty within an acceptable level.

1.1 Why is it so difficult to “face up to” uncertainty?

The following elements combine to make overlooking uncertainty such a common failing:

-

1. We (and the people around us) are biologically programmed to seek certainty with our brains constantly trying to apply memories or experience to predict what will happen next.

These elements are driven by the notion that our brains are “pattern-recognition machines”. To solve problems our natural instinct is to try to apply memories or experience to predict what happens next:

“The brain is a pattern-recognition machine that is constantly trying to predict the near future. To pick up a cup of coffee, the sensory system, sensing the position of the fingers at each moment, interacts dynamically with the motor cortex to determine where to move your fingers next. …. If it feels different, perhaps slippery, you immediately pay attention.

Even a small amount of uncertainty generates an “error” response in the orbital frontal cortex (OFC). This takes attention away from one’s goals, forcing attention to the error. This is like having a flashing printer icon on your desktop when paper is jammed – the flashing cannot be ignored, and until it is resolved it is difficult to focus on other things. Larger uncertainties, like not knowing your boss’s expectations or if your job is secure, can be highly debilitating.” (Rock, Reference Rock2008)

-

2. There may often be some urgency to make a decision; so patience to entertain issues which are not readily resolvable will be limited. It is also possible that the more serious consequences of overlooking uncertainty may have a relatively low likelihood of occurring. A decision maker down playing uncertainty will often be lucky. Short-term reward or personal risk are not necessarily aligned to effective uncertainty management.

Thinking about uncertainty and taking any sort of practical action is inviting additional workload and hassle, and can also delay matters – it is not the easy route. This is often exacerbated by little support from others or quite possibly active resistance.

-

3. Uncertainty is messy and difficult; we do not know what to do about it.

1.2 Uncertainty and decision making

In financial textbooks and applications, there is often the implicit or explicit assumption that risks are known and can be modelled. Those risks that are unknown or unquantifiable often do not receive the proper attention of the decision maker, who may be relying on the model to inform the decision and who may well ignore any caveats or limitations presented on the analysis.

There is the further challenge that there can be a tendency to analyse or model a situation without being fully clear on the purpose. In particular, what is the scope of the problem and what decisions are under consideration?

The following thought process illustrates the challenge.

Is the problem well defined?

Firstly, consider the clarity of the question or problem that you are trying to solve (see Figure 1). It is essential to understand this as clearly as possible upfront otherwise this will lead to additional uncertainty later.

How much of the problem can be quantified?

The next step is to assess how much of the problem can be looked at using modelling techniques. It may be that there is a sufficient quantity of data and understanding of the dynamics of the system that the problem may be considered a “modelling challenge”. But for many real-world problems, one should recognise substantial additional uncertainty that cannot be readily captured by a model and instead turn to a different toolkit to analyse the problem. We refer to this as an uncertainty challenge, where the focus should be on adaptability and understanding the constraints of what is known about the problem (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Question clarity.

Figure 2. The scope of quantification.

In practice, most problems exist between these extremes, and a consideration of where they fall is a helpful first step in working through any analysis.

It is also important to check whether the expert analysing the problem and the decision maker agree on this perspective, which will help later on (see Figure 3). Aligning perspectives is something that will be discussed further in the Bring people with you principle.

Figure 3. Perspectives on question clarity and quantifiability.

1.3 Introducing six key principles for “better” decision making

Our work has identified six key principles for managing uncertainty in any decision and supporting tools in each area. These have been developed primarily with experiences of decision making within the insurance industry in mind, but which are in our view sufficiently generic to apply to other situations.

We believe that to successfully drive improvements in decision making, these principles are relevant to all parties involved in the decision: experts as much as non-experts and decision makers as much as advisors.

Having faced up to uncertainty (#1), it is beneficial in our experience to take a broader view – to deconstruct the problem (#2) by considering the way the question itself has been framed, the dynamics and motivations at play, the stakeholders involved and the potential consequences or knock-on impacts of any decision.

In the absence of certainty, or facts and data, biases can become more powerful (#3, Don’t be fooled). Think of the forceful CEO pushing through a “buy” price higher than the analyst’s valuation; it is easier for the analyst to give way when there is a lack of information about the target company, than when he/she has the full facts and figures to play.

We put forward the idea that models can be helpful, but also dangerous (#4). It is true that much of traditional financial economics favours modelling of quantifiable risks over a better understanding of the unknown, unmodellable and human behaviour.

We do not use a complex model to catch a ball (or famously, a frisbee (Haldane, Reference Haldane2012)); our minds automatically interpret the flight and speed against the background and use prior experience to project where it would land. We do, however, fly in aeroplanes designed, developed and piloted using many models (not least, Newton’s equation for universal gravitation).

Experience, judgement, rules of thumb (“heuristics”) and modelling/analytics are all central to decision making under uncertainty. However, it is also important to have thought through the situations where these work well and vitally where they might break down.

As is ensuring that you control potential downsides and consider the value of optionality within any decision strategy – a principle this paper refers to as “Think about adaptability and resilience” (#5). Finally, “Bringing people with you” (#6) is a pre-requisite for bringing about any change.

So, in what type of situations are these principles useful?

Uncertainty in practice

Uncertainty is a fact of life – and it is not just outcomes that are uncertain. So, often there is uncertainty around the question being asked, the context of the issue being touched on and the dynamics of the problem at hand.

When making an offer on a house, it is not only future house prices that are unknown – so is the rationale behind the seller putting the house up for sale, the extent of work/repairs required, what you and your family value in a home, how other people might value the property in future (proximity to schools, parks, new transport links), your ongoing ability to make mortgage payments, as well as future economic conditions. On a personal level, you may have grappled with the decisions involved with buying a house and experienced how hard it is to do so without a full understanding of the process or having all of the facts to hand. Whilst additional research (e.g. a survey, talking with neighbours, preparing a spreadsheet analysis) might reduce some of the uncertainty, it will not remove it completely, nor will it always bring uncertainty within an acceptable level. Indeed, a degree of uncertainty is present in any decision.

Something as apparently simple as booking a holiday can be fraught with uncertainty about the true service standards of a hotel or the reliability of website reviews. There will be information available that can be used, but often a clear recognition and consideration of what is unknown can be just as valuable in making a good decision.

A “better” approach to decision making

So why focus on “uncertainty” when it is only the combination of luck and time that will tell if a particular course of action (in this case, the offer made on the house) is the “better” one? There are two key objectives of our work:

-

1. To promote “better” decision making where there is uncertainty and provide a toolkit for making “better” decisions;

-

2. To drive awareness and management of adverse outcomes, where uncertainties crystallise.

We believe a “better” decision is one that is made with eyes open – to the degree of uncertainty in any situation, the potential impacts (where known) of these uncertainties crystallising and any mitigating actions to manage uncertainty within acceptable levels for that organisation.

2) Deconstruct the Problem

Some decisions involve situations that are clearly complex with wide ranging uncertainties. Others can appear deceptively straightforward and mislead a decision maker into overlooking important perspectives, assumptions and uncertainties. In both situations, more constructive insights can be achieved from deconstructing the problem into more manageable elements.

Simply breaking a problem into parts can be very helpful (so long as this is not at the expense of also considering the whole). However, three particular deconstruction perspectives are worth considering:

-

The decision-making process: the context and framing of the question; the decision support analysis and modelling and the results communication and interpretation

-

The decision stakeholders: the different people involved with, or impacted by, the decision

-

The assumptions (explicit and implicit) and types of uncertainty involved with the problem and the decision analysis. A structured framework is suggested to support this type of analysis

These perspectives are brought together with the Assumption and Uncertainty Onion.

The other uncertainty principles can be used to provide insights and inform strategies for both the problem as a whole and its component parts.

When looking at a specific decision, there are often uncertainties around the issue itself as well as further uncertainties around the process of analysing the problem.

A starting point may be to look at the different elements of a problem. For example, if buying a house you might consider your requirements (neighbourhood, size, utilities, transport, schools, etc.) and the financing (deposit, mortgage, bills, stamp duty, cost of improvements). Or a government considering a new infrastructure project may look separately at the costs, direct benefits, broader economic benefits, technical challenges and political challenges. However, some of the most insightful, but less immediately obvious issues, can be uncovered by looking at the decision-making process; the people involved and the different underlying assumptions and types of uncertainty.

2.1 The decision-making process

Given our focus on decision making, the deconstruction of the decision-making process is helpful:

1. Framing

What is the question and its context and are both understood properly? The other Uncertainty Principles can provide helpful prompts to provide a further deconstruction:

-

Don’t be fooled: What is the motivation for the question being asked? Are there any known or potential biases? What are the information and understanding gaps (questioner versus advisor)?

-

Models can be helpful, but also dangerous: Is the question amenable to analysis? What are the expectations regarding how modelling might be used and are these informed and realistic?

-

Bring people with you: to what extent is there a shared perspective on the framing of the question, including expectations over how a subsequent decision will be influenced?

As part of the framing, it is also important to consider the broader background, both specific to the actual question and wider “big picture” issues.

2. Analysis and modelling

Is the proposed work understood, both in terms of the approach and the key uncertainties or limitations? The Models can be helpful, but also dangerous and Think about resilience principles offer further assistance here, as does the deconstruction of assumptions and uncertainty types discussed later in this section.

3. Results communication and interpretation

What are the results and how should they be interpreted (in light of the question and analysis)? Communication and appropriate understanding highlight the importance of the last principle, Bring people with you.

There is also the risk of misinterpretation of results which is covered in more detail with the Don’t be fooled principle

2.2 The decision stakeholders

It is useful to consider the different individuals, groups and organisations with a connection to the decision:

-

Who will directly influence the decision maker?

-

Who has opinions or expertise that can provide support to the decision maker?

-

Who will be impacted by the decision?

Understanding all these perspectives helps develop a richer understanding of a problem leading to more informed decision making. The Bring people with you and Don’t be fooled principles both offer guidance to help with this.

It is possible to use simple plots to identify and prioritise attention on relevant stakeholders and unknowns. For stakeholders, the relevant dimensions are “power/influence” and “stake” (respectively, how much that party can affect what happens, and how much they are affected by what happens) – see Figure 4.

Figure 4. Stakeholder identification (French, Maule, & Papamichail, Reference French, Maule and Papamichail2009).

2.3 Assumptions and types of uncertainty

One feature of poor decision making is a lack of rigour in distinguishing between fact and assumptions and the tendency to overlook some assumptions entirely. A particular problem arises with implicit assumptions, those which everyone takes for granted as being both valid and shared by all parties. All too often people are not on the same page, despite everyone’s initial instinctive belief that they are. Such assumptions may only come to light later as the analysis and decision-making process progress, causing frustration and ill-informed views on the most appropriate way forward.

A related but different issue is the challenge in understanding where uncertainties exist when considering a particular problem and decision. The University of Chicago economist Frank Knight (1885–1972) distinguished between risk and uncertainty in his Reference Knight1921 work Risk, Uncertainty and Profit (Knightian Uncertainty) (Knight, Reference Knight1921). In essence, he defined risk as where you know the probabilities of different outcomes and uncertainty as where you do not. Some things are fully known, e.g. probabilities of outcomes from throwing an unloaded dice, while others are, to all intents and purposes, unknowable (or at least unknowable in the timeframe of the decision). In practice, there are many variations and levels of uncertainty in between which in turn require different approaches to management.

It is possible and useful to deconstruct the assumptions and types of uncertainty in a problem separately. However, greater value is possible by looking at the two together.

Assumptions

People have a natural tendency to focus on outcomes. This can mean important assumptions regarding the starting position are overlooked. There may also be a lack of rigour in considering whether a given approach will be effective in leading to the desired outcome.

In deconstructing assumptions, it is suggested a problem can be looked at as a journey:

-

1. Where are we now? (starting point)

-

2. Where do we want to get to? (end point)

-

3. How are we going to get there? (effectiveness of the solution to get to the end point)

In all cases, particular attention should be paid to identifying implicit assumptions. What is being assumed to be true that is not being discussed and has the potential to undermine the validity of a decision?

Types of uncertainty

Uncertainty is a broadly defined and applied term; different types require appropriate responses. Merton (1936) considered this aspect as early as Reference Merton1936 and, incorporating a number of other perspectives and influences (French Reference Frenchn.d.)Footnote 1 , we offer the following categorisation of types of uncertainty:

-

Limited knowledge due to the unpredictability of fortuitous outcomes. This is also referred to as stochastic or aleatory variability (or in layman’s terms, randomness)

-

Limited knowledge due to ignorance. This may arise where there is inadequate information or where something is effectively unknowable. This is also referred to as epistemic (or knowledge) uncertainty

-

Modelling limitations, including compromises in capturing the reality of a real-life system (both model design and parameterisation judgements)

-

Ambiguity, where lack of clarity over the problem framing and analysis assumptions may lead to unintended consequences

-

Errors and other operational uncertainty. These can occur at any stage and take many forms, for example, the use of incorrect data, a flaw in a computational process or a typographical mistake

-

People uncertainty, arising from a lack of awareness of possible hidden agenda or unintentional biases. These are discussed in the Don’t be fooled principle section

-

Social and ethical uncertainty. Linked to people uncertainty but taking a broad societal perspective. Examples include self-fulfilling and self-negating prophecies – in which public statements change social views so substantially that the prophecy is no longer valid. Or basic values – in which the realisation of one’s fundamental values is so important as to preclude any consideration of the consequences

Where a model is known to have limitations this might be labelled as “uncertainty” (and is included in the above list) but is in fact deliberate and perhaps may be considered as relating more to “assumptions”. Similarly ambiguity is entirely avoidable. This overlap with assumptions illustrates why there are benefits in looking at assumptions and types of uncertainty together.

The above does not differentiate between degrees of uncertainty and this is also a valid and important potential deconstruction. The benefit of using complex models to help inform optimal strategies is greater in risk (known probability) situations. Conversely the relative simplicity of certain heuristics (rules of thumb, intuitive judgement, etc.) will come to the fore insituations with greater uncertainty and unknowability. This is discussed further with the Models can be helpful, but also dangerous principle.

Combining assumptions and types of uncertainty

The inter-connection between assumptions and types of uncertainty suggests there is value in considering both together. This is illustrated below (Figure 5), where assumptions can be identified and their uncertainty categorised:

Figure 5. Assumptions and types of uncertainty.

For example, we might consider moving house, as discussed in the Face up to uncertainty principle:

-

Unpacking assumptions

-

○ Where are you now? Existing space adequacy, current location suitability, current house value (if applicable), current finances, career prospects

-

○ Where do you want to go? Perceived requirements (space, location criteria, etc.), time constraints, financial position (including career progression), future flexibility?

-

○ How are we going to get there?

-

▪ Property availability (location, size, features, price, etc.)

-

▪ Selling existing property (demand, price, pre-sale improvements?)

-

▪ Raising deposit and mortgage financing

-

▪ Research (reviewing areas, surveyor’s report, improvement costs, bills, etc.)

-

▪ Financial analysis (spreadsheet of costs and future finances)

-

▪ Relationship management: estate agent, buyer(s), seller, parents/family?

-

-

-

Categorising uncertainties

-

○ Limited knowledge due to the unpredictability: future house prices, interest rates

-

○ Limited knowledge due to ignorance: hidden problems (partly mitigated through survey, search, etc.), future space needs, future job changes

-

○ Modelling limitations (financial analysis): sale price, buying price, cost of essential or desirable improvements, future bills, earnings, interest rates

-

○ Ambiguity: how clear are your criteria?

-

○ Errors: overlooking costs, spreadsheet analysis errors

-

○ People: buyer, seller, agent, family

-

○ Social and ethical: crime levels, environmental factors

-

It is of course possible to create significant complexity through such an approach. However, a rigorous deconstruction can identify key assumptions and uncertainties that may otherwise by missed, or at least not be properly understood or managed.

2.4 The assumption and uncertainty onion

To help combine the decision process, stakeholder, assumption and uncertainty type deconstructions, we suggest the use of a vegetable analogy: the Assumption and Uncertainty Onion (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The assumption and uncertainty onion.

Consider a problem as an onion with the outer layers containing information regarding the context and key aspects of the approach to be taken to analyse the problem. The inner layers contain more technical detail which either requires specialist expertise or is simply less important than information in the outer layers. A key point about the onion analogy is that many assumptions are likely to be below ground and hidden from the non-inquiring mind. By deconstructing the problem it becomes easier to identify the implicit assumptions and highlight those that are sufficiently important that they belong in the outer layers.

Engagement with the outer layers is essential for everyone (see the Bring people with you principle). A decision maker not prepared to contribute to the outer layer activities is unreasonably abrogating responsibility to others and cannot expect to make well-informed decisions. Likewise “experts” need to do their part by helping identify the outer layer information for a given problem, and do their part to make it as relevant and comprehensible as possible.

3) Don’t Be Fooled (Un/Intentional Biases)

Things are not always as they seem. Without careful thought it is easy to find decisions (or support for decisions) being corrupted by deliberate agendas or a range of unintentional biases. Understanding where a decision maker or an advisor can be fooled is essential to reducing human-derived uncertainty. The subsequent communication strategy for each party should be adapted accordingly, recognising both perspectives.

Real-life situations often involve the questioner and expert having different knowledge and perspectives. An open declaration of all information and issues may be encouraged from a formal professional perspective, but may not be an optimal nor reasonable approach for one or both parties. In some situations, understanding “the game” is important so as not to be fooled, but also to ensure intelligent practical application of professional standards.

Unintentional biases can also be powerful corrupters of good decision making. The awareness of the manner in which our brains are designed to instinctively take decisions helps us to identify common biases and traps that can undermine the quality of these decisions. We categorise some of these cognitive effects and suggest some of the ways in which we can manage our approach to avoid the dangers presented.

This principle covers two different but important elements: the challenge of managing uncertainty where there are deliberate efforts made to mislead; and the wide ranging ways unconscious bias can corrupt well intentioned decision makers and their advisors. Often (possibly always) these two factors will arise at the same time in any given situation, with the decision maker and advisor deliberately or sub-consciously biasing their judgement in order to align with expectations and agendas. For the purpose of describing and explaining them in this section, we have kept them distinct.

We first consider deliberate agendas and information asymmetries and the role of communication. In particular we highlight the importance of two-way communication and make observations on how to “play the game”.

We then look at the wide range of unintentional cognitive biases, looking at when they can arise and how awareness itself is perhaps the main technique for countering their potential harm.

It is worth noting that while professional ethical codes require an individual to act in a manner that is free from undue influences and bias, the reality is that such codes can only meaningfully be interpreted quite narrowly. The full range of potential sources of influence and bias is diverse and clearly addresses a much wider class of circumstances than envisaged under professional ethical codes.

3.1 Intentional biases and playing the game

The classical way of thinking about communication – perfecting the one-way presentation

Clear communication is often interpreted as a one-way activity, particularly in the context of professional advice. Hence, professional standards are crafted in terms of setting out information in “a clear and comprehensible manner” and examinations assess the ability to present concepts clearly to lay-readers. In the context of uncertain estimates, the need to explain probabilistic concepts in an intelligible fashion is key, particularly where probabilities are small, and underlying model and parameter choices may be significant. Hence professionals develop standardised approaches to expressing ideas, often building on precedents developed over time, and the evolution of certain terms of art.

In this case the advisor imparts information and the clientFootnote 2 absorbs it. The advisor wants the client to benefit from the greatest possible understanding in the most efficient fashion and the client has an objective of obtaining the advisor’s best advice given the information available. Constraints and incentives are aligned with these goals, so can be ignored as they do not distort the position. For example, the exercise is seen as a one-off, with neither sides’ actions taking into account the effect of prior nor subsequent work.

Game-theoretic approach – 2-way communication strategies

Real-life communications involve two or more parties, each with different pieces of information and with their own incentives, objectives and payoffs.

The advisor may:

-

Know the implicit assumptions underlying the work

-

Constrain the amount of time or effort that they wish to put into the work (e.g. because their remuneration is not linked to the amount of work done)

-

Conversely seek to increase the amount of work they do in order to increase their remuneration

-

Wish to defend a previously held view and avoid embarrassment to themselves

-

Wish to break with a previously held view (probably of another) or store up margins for recognition in future

-

Be aware of how far they might be prepared to modify their advice to accommodate or support a desired outcome by their client sponsor

The client may:

-

Know the consequences of different outcomes

-

Know the opinions and estimates of others, including other advisors

-

Want a particular outcome to avoid embarrassment to themselves now

-

Want a particular outcome to provide a cushion against potential embarrassment in future

-

Know what information has not been provided to the advisor

-

Have a view regarding whether a particular advisor tends to be more or less conservative with their advice; has a good or reliable reputation (based on their own experience or that of others); tends to be flexible in response to challenge

These influences may also link in with relationships between advisor and client, either at a corporate or a personal level that may be sustained over a number of years, with mental accounting of favours granted or owed providing a successive link between interactions.

In addition, further complexity may arise as there may be multiple client stakeholders, multiple advisors and potentially agents and layers of sub-ordinates to decision makers who may introduce a form of “friction” to the communications.

As a result, communications need to be seen as a form of negotiation or transaction, often broken down into a series of sub-transactions or negotiations.

Theoretically optimal strategies for 2-way communication

How then does the advisor determine the most appropriate strategy for navigating this scenario, where each party has information that the other lacks, and there may be characteristics of the behaviour of the other that are known or unknown?

While classical theory might suggest that the optimal approach is to be both predictable and transparent with the information possessed, a game-theoretic view suggests that this may not be ideal. Indeed, many experienced advisors will have experienced or observed cases where clients have taken advantage of a naïve advisor, and a few will have war stories to tell. But equally, an inappropriately cautious or aggressive approach from an advisor can prove inefficient and counterproductive.

In practice, we often observe a complex ritual during which each party seeks to use their own information advantages to elicit desired information from the other party. The advisor and client may not initially have the same concept of what is a proper request; so the initial exploratory language adopted by both sides may be deliberately ambiguous or cryptic, augmented by non-verbal signals and other indirect means. These serve to allow retractions to be made and positions altered under the guise of innocent misunderstandings.

Such a process is not unique to advisor–client relationships, but pervasive through human interactions. Psychologists have studied such behaviours in other contexts such as courtship rituals and interactions between citizens and law enforcement agencies.

Here are some observations on the suitable tactics and strategies to adopt in this complex 2-way communication environment:

-

1. Unilateral full transparency can be a weak tactical approach for an advisor as the client can take advantage of the advisor by persistently seeking to influence advice in one direction.

-

2. Full opacity can therefore be equally unhelpful. While it might provide an initial tactical advantage, it can undermine trust and therefore weaken the strategic position over the longer term.

-

3. Some ambiguity can be helpful, particularly during early stages of communications, while each side builds trust with the other. Excess or persistent ambiguity however can undermine trust and frustrate meaningful progress. Too much ambiguity can confuse others to your true position, inhibiting their ability to share information, while persistent ambiguity impedes progress towards decision making and action.

-

4. Consistency of approach over time builds trust and credibility with the counterparty, so yields strategic benefits to the relationship and the communication framework.

In summary, deliberate ambiguity or adoption of a position may have some justification and may be a practical necessity in active communication, but needs care in its application to avoid straying over the line into what might be considered unprofessional or unethical behaviour. The context of the decision, the decision support being sought and the relationship of the questioner and the advisor all need to be considered. Whether justified or not, being alert to potential intentional bias is important for all parties.

3.2 Unintentional biases and traps

There is a rich body of research covering cognitive bias. In the context of decision making and uncertainty it is helpful to categorise the different biases and heuristics (rules of thumb) into three groups (an example of another uncertainty principle “deconstruct the problem”):

-

Latent framing: biases and heuristics that influence the perception of a problem and expectations of the outcome

-

Traps: general biases and heuristics that can deceive the decision maker and advisor

-

Over-interpretation: biases and heuristics relating to reading too much or too little into data

Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011), provides a helpful introduction to this field, setting out the results of many years of behavioural research. In essence, he identifies that the human brain has a fast, instinctive decision-making capability, necessary for survival and to manage the many decisions that we must take each day. In addition, it is also capable of a much slower, deliberative and logical manner of thinking. The former, which he terms “System 1”, is always on, whereas the latter “System 2” requires effort and is often not deployed because our brain is programmed to conserve energy (or is “lazy”).

What is clear is that certain tools and techniques can be effective at countering specific biases, and to achieve this there is an over-arching theme of stimulating “System 2”. The very act of identifying the potential presence of a particular bias stimulates this more structured approach to thinking about a problem and can go some way towards mitigating the impact of these biases on a decision.

Although there are no simple routes to avoid the tricks presented by the manner in which our brains operate, an awareness of the various hazards that exist can help us to be on our guard. In a professional advisor/decision-maker relationship context, we recommend taking steps to turn on our System 2 approach to problems.

Some examples of ways of doing this might be:

-

Independent challenge of work

-

Forcing yourself to document and explain your thinking

-

Avoiding rushing to conclusions

-

Use of checklists

-

Asking the counter-factual questions – what if this was wrong, or what would need to happen for this to be very wrong?

Note that some instinctive biases and heuristics (rules of thumb) can be useful tools insituations involving uncertainty and unknowability, avoiding being fooled by the spurious complexity of approaches which are only valid with greater underlying knowledge. This is discussed further with the Models can be helpful, but also dangerous principle.

We conclude this section with a brief summary of some of the common biases and traps identified in preparing the paper and recommend further reading around this topic for a more in-depth understanding. Two notable sources were Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast and Slow (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011) and the 2012 Lloyd’s paper “Cognition Minding risks: Why the study of behaviour is important for the insurance industry” (Weick et al., Reference Weick, Hopthrow, Abrams and Taylor-Gooby2012). This list is not intended to be exhaustive, but we recommend readers familiarise themselves with them. Reviewing these biases and traps when giving advice or taking decisions may provide a helpful means of avoiding them.

Latent framing

-

Affect heuristic: the tendency for people to use their personal likes and dislikes to form beliefs about the world

-

Anchoring: the process of using a starting point for evaluating or estimating unknown values

-

Confirmation bias: tendency to seek evidence that is compatible with a given view

-

Halo effect: the tendency to like (or dislike) everything about a person, including their opinions

-

Myopic loss aversion: a phenomenon whereby investors are particularly concerned with the potential for a short-term loss, even in the context of long-term investments

-

Trusting intuition: the tendency for people to have a lot of confidence in their intuition

-

Status quo bias: the preference for things to stay the same

-

Sunk cost bias: costs incurred in the past are used as a justification to continue investing in suboptimal projects or strategies in the future

-

Survivor’s Curse: tendency for the lucky to survive and have misplaced optimism

Traps

-

Gambler’s fallacy: the tendency of decision makers to underestimate the probability of a repetition of an event that has just happened

-

Illusion of validity: the use of evidence to make confident predictions even after the predictive value of the evidence has been disproved

-

Law of Least Effort: the tendency for people to seek the easiest way possible to complete a task

-

Mean-reversion bias: when decision makers assume that over time, a trend has to return to the mean

-

Planning myopia: the tendency to consider consequences over a too restricted time horizon.

-

Priming: purposefully triggering thoughts or ideas

-

Temporal discounting: the greater the delay to a future reward, the lower its present, subjective value

-

Winner’s Curse: tendency for winning bidders to overpay where there is incomplete information

Over-interpretation

-

As if bias:Footnote 3 the potential to be optimistic when restating historic behaviour due to exposure revisions or past misfortune

-

Availability heuristic: the tendency for people to respond more strongly to risks when instances of those risks are more available to them (from memory, imagination, media, general social discourse, beliefs about the world)

-

Causal thinking bias: tendency for people to seek patterns and explanations rather than believe in chance

-

Hindsight bias: the false belief that events are more predictable than they actually are

-

Illusion of skill: the tendency for people to mistake good luck for skill

-

Small probabilities: a group of biases that can arise when people reason about rare events. Small probabilities tend to receive too much, or too little weight depending on the decision context

4) Models Can Be Helpful, but Also Dangerous

“All models are wrong, some models are useful” George E. P. Box

Where true uncertainty exists, complex models can be dangerous. Instead the use of simple models or rules of thumb in the hands of an experienced practitioner can be a better approach. Simple rules can offer an understandable and clear approximation to the problem, and the experience of the expert helps to gauge where the model will work well and where the assumptions might fall down and alternatives need to be considered.

Understanding the context of the problem and the influence a model may have on a decision is key. Models can still be useful insituations where there is significant uncertainty, or even unknowability. For example, value may still be obtained from comparing options or through a better understanding of a process or system.

Simplified models or rules of thumb will have inevitable limitations. The uncertainty can be mitigated through our next principle: Think about adaptability and resilience.

The practical challenges of working with complex models are illustrated by looking at the use of Economic Capital Models and catastrophe models.

Imagine trying to direct air traffic into Heathrow airport without the tools used to project the future movements of aircraft. There may be situations that arise where these are inadequate, but there are safety processes in place where manual intervention can take over to avoid a disaster. Or imagine trying to plan for the safe transfer of perishable goods across a large network of supermarkets without a model to predict demand and to optimise the transport routes.

Models can be very useful and allow us to do things that would otherwise not be possible.

A model might be defined as an abstraction of a system that makes appropriate simplifying assumptions for the purpose of understanding the underlying process. The output from a model, or the associated understanding of the system, may directly or indirectly influence decision making.

Taking the broadest perspective, a model can range from a complex statistical tool with a number of dependency assumptions to a simple rule of thumb or heuristic.

Models can be useful in a number of ways, for example:

-

Estimation of values (or patterns), e.g. finding the “best fit” by analysing observed data

-

Prediction of future values, e.g. forecasting the future claims costs for an insurance contract

-

Comparison and calibration: better/worse, bigger/smaller, etc., e.g. has an insurance exposure increased or decreased since last year; how much will the claims costs of an insurance contract increase if additional coverage is included; or is company A more profitable than company B

-

Optimisation: what is the preferred option for a given set of objectives and constraints

-

System understanding, e.g. how changes in exchange rates will affect the financial results of a company; or how might a cyber incident impact an insurance portfolio

Given the broad way in which models can be used, sweeping statements about the usefulness (or danger) of a given model are not possible. It is vital to understand the context of a decision, the quality and appropriateness of the model and the way in which the model might influence the decision.

The use of a poor model, or the inappropriate use of a good model, can give misplaced confidence or insight to a decision maker and be dangerous. These issues are greater where there is uncertainty.

4.1 Risk versus uncertainty and the use of models

With the Deconstruct the problem principle we discussed types of uncertainty and, in particular, Knightian Uncertainty. This makes the distinction between “risk” where you know the underlying probabilities and “uncertainty” where you do not. The insights of Gerd Gigerenzer,Footnote 4 the renowned German psychologist, are helpful in understanding the usefulness of models.

He argues that the concept of “optimising” is only truly possible where you know the underlying probabilities, i.e. in risk situations. However in most real life situations this is not the case. Even where we have a lot of statistics we do not know the true probabilities. The further away you move along the risk-uncertainty spectrum towards complete “unknowability”, the less useful complex models become.

Gigerenzer highlights the value of heuristics in uncertain situations. Wikipedia defines heuristics as “any approach to problem solving, learning, or discovery that employs a practical method not guaranteed to be optimal or perfect, but sufficient for the immediate goal. Heuristics can be mental shortcuts that ease the cognitive load of making a decision, for example using a rule of thumb, an educated guess, an intuitive judgment, guesstimate, stereotyping, profiling, or common sense”.

Heuristics are what most people use in the real world, but this is not to say all are good. There can be bad heuristics (just as there can be bad complex models), and good heuristics used inappropriately given the context of the decision or the lack of experience of the decision maker. In situations involving uncertainty they should not be seen as second best, rather their merits should be considered alongside more complex modelling alternatives.

Gigerenzer was involved with a Bank of England project on the use of simple heuristics which led to Andy Haldane’s The Dog and the Frisbee paper referred to in the Face up to uncertainty principle (Haldane, Reference Haldane2012). This paper highlights the benefits of simplicity and how, for example, a simple heuristic restricting bank leverage ratios would have been at least as effective as the complex (and expensive) model-based rules that are promoted in banking regulation.

Key takeaways are:

-

Simple heuristics may often be as effective as complex models where there is high uncertainty. “The simplest solution tends to be the right one” (Occam’s razorFootnote 5 )

-

If one (or two) heuristics work, then there is huge benefit in simplicity (the marginal value of additional heuristic and complexity may be small so not useful)

-

If the problem is one of “risk”, or in games that are fully defined, then complex modelling is much better, e.g. if playing roulette or black jack at a casino then do your calculations – don’t use heuristics!

It is important to think about modelling and heuristic options as a toolkit. The specific situation and context are key to the choice of tool(s), hence the experience and wisdom of the decision maker (and adviser) is paramount.

4.2 When to use a model

The Face up to uncertainty principle introduced the distinction between problems that are largely quantifiable (“modelling problems”) and those that are largely unquantifiable (“uncertainty problems”). It is important to understand what is unquantifiable and hone your “unknowability radar”:

-

Identify limits to knowledge

-

Spot bad (actuarial) science

-

Spot hard problems

Your unknowability radar can be used to distinguish between smooth and knotty problems – those that are easy to solve and those that require additional care. It will also enable us to identify unknowable problems – those that are ultimately impossible to resolve with any confidence.

Table 1. Examples of distinguishing problem unknowability

As outlined at the beginning of this section, models can be useful in different ways. If a problem is unknowable there may still be valuable insights from comparison exercises and system understanding through modelling, but the potential for inappropriate and dangerous use is obvious.

Do not be afraid to say where modelling cannot contribute to a decision: Face up to uncertainty. More constructively it is important to consider how uncertainty can still be managed through the use of good “rules of thumb”. However your rules of thumb may turn out to be poor so it is also important to Think about adaptability and resilience, our next principle.

An illustration of unknowability

In their paper “Ersatz model tests” (Jarvis et al., Reference Jarvis, Sharpe and Smith2016), the authors consider the following problem. We have ten historic observed losses 26, 29, 40, 48, 59, 60, 69, 98, 278, 293 (listed in ascending order). The mean of these observed losses is 100. What is the value of a 1 in 100 loss (i.e. there is only a 1% chance of the next, 11th, loss being bigger)?

Consider three scenarios:

-

Green scenario. The losses come from an exponential distribution with a mean of 100.

The 1 in 100 (99%ile) of this distribution is 461 (to the nearest whole number).

-

Amber scenario. The losses come from an exponential distribution with an unknown mean.

The observed mean is 100 but the true underlying mean could be higher or lower (we could have been lucky or unlucky). We could estimate a distribution of the mean (formal parameter uncertainty) and calculate (or simulate) the 1 in 100 number. This will be more than 461.

-

Red scenario. We know neither the underlying distribution nor the mean

The observed mean and standard deviation are both exactly 100, consistent with an exponential distribution. But we don’t know either. We could select a distribution, or an ensemble of distributions, and assume the mean has some parameter uncertainty. This could give a range of results but it is likely the 1 in 100 loss will be greater than for the amber scenario.

The extra uncertainty in the red and amber scenarios relates to a lack of knowledge, rather than inherent randomness (referring to our list of uncertainty types in Deconstruct the problem: “Limited knowledge due to ignorance” rather than “Limited knowledge due to the unpredictability of fortuitous outcomes”).

It is rare to find practitioners assuming they are operating in anything other than a green scenario world (even though they might acknowledge this assumption). Distributions are fitted to observed data and results from the tail of these distributions are used with limited challenge. More sophisticated approaches may appear to counter this by incorporating, for example, parameter uncertainty. However, such methods may be argued to be somewhat spurious as decision makers can be misled by the implied accuracy with the unknowability being apparently addressed.

The real world is always red. However, this does not mean model use is always inappropriate or dangerous. But it does require careful consideration of the context and the influence model results will have on a decision. In practice complex models can be used intelligently by experts along with other heuristics to ensure limitations do not detract from good decision making.

4.3 Example: economic capital models

It is increasingly common for (re)insurers around the world to use an Economic Capital Model to help inform business strategy. This is particularly common in Europe where there are potential regulatory benefits from it (such as lower capital requirements). A typical Economic Capital Model will be a probabilistic model that looks to quantify the capital buffer that the company needs to hold to be able to withstand potential losses to a specified tolerance level. The tolerance is usually quite extreme. Under the European Solvency II regulatory regime, for example, the tolerance is set at a 0.5% probability level over a 1 year time horizon. That is, the model is attempting to quantify a 1 in 200 year loss scenario for the company.

The calibration of Economic Capital Models is reliant on experience data. Availability and consistency will vary, but it is unusual to have more than 15 to 20 years of data that can be considered to be relevant for modelling the company as it is today. The models attempt to extrapolate from this experience to what a 200 year level loss could look like. This extrapolation is clearly very uncertain.

Some model components use elegant techniques to try to get around this, using methodologies that can be based on better datasets. Natural catastrophe models are an example, which are typically based on physical models. These can make use of extensive weather datasets, such as for wind speeds and rainfall which have been captured over many years. However, with climate change and other trends, even this is flawed.

Then there are unknown unknowns, things that we have not considered and that have not occurred yet. Some allowance may be made by introducing loadings for Events Not In Data (ENID). However, this is inevitably highly subjective.

Unsurprisingly, the overall 1 in 200 estimate is extremely uncertain and taken literally is an “unknowable” problem as highlighted by our red scenario.

It is worth noting that regulators use a “rule of thumb” to sense check capital model results. It is called the Standard Formula and is a set of leverage factors relative to premium, reserves and assets. This is a useful tool in the hands of an experienced practitioner to make sure that the results of an Economic Capital Model seem sensible relative to peers and market norms.

The unknowability issues are well known and it is well recognised that the 1 in 200 estimate produced by an Economic Capital Model is not very accurate. Despite this, many insurers have invested heavily in developing Economic Capital Models and use them extensively in running their business. This is because the ways in which the models are used are not always reliant on the 1 in 200 being precise. Often it is the movement in this risk measure is what really matters, rather than the absolute number.

Change of business strategy illustration

Your model might indicate that pursuing a certain business strategy might increase your 1 in 200 risk measure from $500 to $600 million. Instead of fixating on the dollar number, it may be better to view this as the risk increasing by about 20%. Though the absolute number, $600 million, might suffer from the accuracy problems described above, the relative movement, 20%, is likely to suffer less and be more accurate.

Now let’s consider an alternative strategy, which is expected to lead to a similar increase in profitability. We see from testing this in our model that it would increase the 1 in 200 from $500 to $700 million. This is a 40% increase. Our model is suggesting that the first strategy is likely to be better from a risk versus return perspective. We cannot guarantee for certain that the first strategy is the best as it is still based on a model, but using the model in this way should be far more resilient than trying to anchor on the precise number.

Investment optimisation illustration

A real-life example was seen with an insurer who was looking to optimise their investment portfolio. They set up a model and it suggested a portfolio that would give the highest return for a specified level of risk. The optimal portfolio was seen to give a significant increase in return for broadly the same level of risk as the current portfolio. On inspection, it could be seen that the existing portfolio was over concentrated in certain sectors and was not as efficient as this new portfolio.

However, the model was seen to be very sensitive. A series of sensitivity tests were carried out where the model was based on alternative economic assumptions. Worryingly, each alternative test resulted in a different optimal portfolio. The alternative assumptions were all plausible, so it was not clear which portfolio would be best. But it was seen that the proposed new portfolio did perform reasonably well under all the alternative scenarios and in all cases looked to be far better than the existing portfolio. So whilst the company could not be certain that their new portfolio was optimal, they could be reasonably confident that it would be a significant improvement on their existing portfolio. Despite its uncertainty, their modelling had guided them to a better portfolio than they would have had without it. Using a model in this way links in closely with the ideas in the “Think about adaptability and resilience” section.

So despite their clear limitations, models can be useful if used right. Using risk models like this can help reinforce a risk culture and drive appropriate behaviours, leading to companies that are better able to manage risk.

4.4 Example: natural catastrophe models

There are well-publicised failures of the catastrophe models that are used by the insurance industry, such as their failure to allow for the possibility of flooding in New Orleans from the levees breaking in Hurricane Katrina or very recently with the rainfall from Hurricane Harvey.

However, it is well accepted that the use of these catastrophe models has given insurers a better understanding of their exposures and accumulations and the number of insurer failures from natural catastrophe losses has declined markedly since their adoption.

Knowledge of engineering and science is continually expanding. For example, the US Geological Survey has recently helped develop a better understanding of earthquakes in the US – which has been incorporated in recent commercial catastrophe models. This and other developments are expected to lead to more accurate modelling, or improved insights, over time.

For rare events, by definition, there is always limited data and this can be interpreted in different ways. For example, the New Madrid earthquakes of 1811 to 1812 could be treated as either three unrelated earthquakes spaced a few months apart or as a series of connected events. The view taken will make a significant impact on your modelled distribution – and understanding these uncertainties is key to making the best use of the historical data.

A similar example is catastrophe modelling that previously considered a point estimate on the likelihood of flood defences failing under particular stressed conditions. These were later developed to be based on a range of likelihood estimates (e.g. “cautious”, “mid-range” and “optimistic”), as assessed by a focused group of experts. This led to a much wider range of uncertainty estimated in the modelling results – allowing decision makers to better understand these inherent uncertainties.

This uncertainty can be problematic if the model is needed to give a point estimate, such as for calculating a price for an insurance contract. In this situation we need to establish protections so that we can be resilient to the possibility of the model being inaccurate, for example, by using prudence margins or purchasing reinsurance. This links to the ideas from the Think about adaptability and resilience principle.

A key positive feature of catastrophe models is that they break the problem down into a series of areas – each of which is focused on a single domain of knowledge. This links in with the ideas in the Deconstruct the problem principle. This structured approach helps with model conceptual understanding and allows individual parts of the model to be developed in isolation as new research is available.

As users of catastrophe models, our role is to assess the overall appropriateness of the output and to clearly communicate the known limitations and uncertainties.

5) Think About Adaptability and Resilience

In the face of uncertainty it is important to adopt resilient thinking and forward looking planning. This builds preparedness and adaptability to deal with the consequences of decisions that may not turn out as hoped. While such surprises can be unwelcome they may also present opportunities.

Thinking about adaptability and resilience is not just about risk mitigation or avoidance, but also the ability to take advantage of new circumstances.

We Deconstruct the problem to suggest an Adaptability and Resilience Toolkit covering the things you can control and those you cannot:

Things you can control

-

Have a clear strategy and approach to uncertainty

-

Think about what can go wrong? “How much we can afford to lose”, “what will hurt/kill me”?

Things you cannot control

-

Build in strength and options. “What makes us stronger?”, “What might make us re-think the strategy, and what options do we have?”

-

Plan for outcomes (not causes). The potential causes may be too complex, uncertain or unknowable to make a complete analysis realistic

5.1 Introducing the adaptability and resilience toolkit

In the face of uncertainty, it is important to be resilient to adverse outcomes (see Figure 7). It is also valuable to be able to adapt and capitalise on opportunities following changing circumstances and expectations.

The traditional ERM framework focuses on risks that can be identified, controlled and quantified. Unfortunately, the world does not divide neatly up into risk and sub-risk categories, and it may be that the residual risks are overlooked, which is where the “adaptability and resilience toolkit” comes in. It helps us identify and capitalise on upside risks, when treading in uncertain waters, as well as protect against downside risks, when navigating uncertain waters.

5.2 Clear strategy and approach to uncertainty

In his book, “Good Strategy/ Bad Strategy” Richard Rumelt (Reference Rumelt2011) explores successes, and failures, in corporate strategy. Quoting John Kay, writing in the FT (Kay, Reference Kay2012):

“For Prof Rumelt, the kernel of a strategy is the diagnoses of a situation, the choice of an overall guiding policy and the design of coherent action. A guiding policy is an element of strategy, but is not a strategy until it is translated into specific actions. One of the silliest remarks in business is “strategy is easy, implementation is difficult”. But strategy that lacks a clear path to implementation is not strategy at all, just wishful thinking”.

The nature of the strategy that should be adopted in the face of the uncertainty will vary according to the decision and its context. In a commercial context, the chosen strategy will depend on the organisation’s commercial (or other) objectives, market opportunity, stakeholder expectations and available resources. It will also depend on the organisation’s risk appetite and attitude to uncertainty. A key point in Rumelt’s thinking is that a strategy alone will not determine success – it is critical to understand the issues at stake, and have a set of actions to support your overarching goal.

When it comes to uncertainty, as time progresses the situation and outcomes will change as new information comes to light. It may or may not be possible to predict such changes, but it is important to build optionality into your game plan – actions you will or won’t take to reflect on the new circumstances and adapt where appropriate.

In a negotiation, for example, it is important to understand the situation (see 2-way communication in the Don’t be fooled section) and decide on a strategy regarding the information you are prepared to reveal and when, the outcomes you consider acceptable, and your overall approach to making and responding to proposals.

Some situations present additional options and challenges.

In Dr Keith Bickel’s book “Mastering Uncertainty: The three Strategies You Need to Know”, (Bickel, Reference Bickel2011) he proposes three alternative strategies:

-

Pioneer strategy: High Risk/ High Reward, Market Shaper

-

Pouncer strategy: Medium Risk/ Reward, Marketing Powerhouse

-

Hedging strategy: Medium-Low Risk, Willing Contrarian

In the 1990s demand for personal handheld phones was uncertain. Nokia (a pioneer) moved early to “make” the market. Ultimately, they were not as successful as Apple or Android (pouncers) who redefined the product, once demand had stabilised and investment costs were lower, creating change in consumer demand that Nokia could not keep pace with. By contrast, hedgers keep options open by investing in one or more areas that run counter to their current strategy, for example, Tesco marketing mobile phones as well as acting as a distribution channel.

When faced with areas of significant uncertainty, for example, Cyber Risk (see below), a fourth strategy is also available to you: “avoid”. However, this strategy can result in an extremely destructive outcome, e.g. Kodak’s avoidance of the digital imaging market which turned out to be the winner.

To put the above strategies into perspective, we consider these with regards to “cyber” risk and how various players in the market have adopted one of the above strategies.

5.3 TO cyBEr or NOT TO cyBEr?

While cyber risks affect all organisations, our focus here is on insurers who have considered and chosen their commercial strategy to take on (or to avoid) cyber risk.

Financial Losses from cyber attacks (an attack from one or more computers, on others) are significant and have been increasing rapidly in recent years ($5 billion estimated damages in 2017, projected to increase to $1 trillion by 2021).

The scale of economic vulnerability to cyber attacks is not only material but also very highly uncertain: for example, Lloyd’s recently estimated that the potential economic impact of a malicious hack on a cloud service provider ranges from $15 to $121 billion (Maynard & Ng, Reference Maynard and Ng2017), highlighting factors such as the nature of the industry sectors exposed and duration of the outage. This is confounded by contagion risk – such that it is not clear where an attack might arise from, or why. For example, experts believe the “NotPetya” attack in 2017 started out as a politically motivated attack on Ukraine, targeting power stations (Chernobyl), banks, ministries and transport systems. However, it was designed to spread quickly and did – with companies such as Cadbury’s, Maersk, DHL, DLA Piper and a British advertising company all finding they were affected.

In a capital rich and highly competitive global insurance and reinsurance market, cyber risk and the extent of the associated uncertainty presented a market opportunity. Some players, such as AIG, Beazley, Hiscox and Swiss Re amongst others, adopted a “pioneer” strategy and moved early. This allowed them to start to develop the expertise, frameworks, tools and partnerships required to manage exposures and the associated uncertainty. Others, such as Berkshire Hathaway, have chosen to avoid or strictly limit exposures: Warren Buffet said that “cyber is uncharted territory” and the risk is going to get “worse, not better”.