Preamble: the disciplined versus the performing body

In this article, I want to treat the Egyptian 25 January revolution as a struggle over the right to produce signs within an Egyptian cultural landscape long plagued by the state's attempted monopoly over meaning. If one accepts this premise, then what happened in Tahrir Square in early 2011, those most memorable eighteen days that led to the eventual toppling of Hosni Mubarak, should call for an inevitable revisiting of Foucault's notion of the ‘disciplined body’. Power, according to this view, pays great attention to the organization of space, and this organization, in turn, unveils social hierarchies not only through the places where bodies are either allowed or banned, but also through the disciplinary domains designed for modelling and stereotyping humans and training their bodies for preset conditions and functions.Footnote 2 Power thus constructs the body through its discourse, subjects it to constant surveillance, and controls its action through mechanisms of discipline and training that guarantee its docility and social management.Footnote 3

In contrast to all this, the Egyptian revolution has, so to speak, lifted the curtain on an explosive, performing body that has slipped away from the grip of power and sought to challenge its sociocultural and linguistic constraints. Like an actor onstage who acquires a new sense of agency through performance, the individual citizen in revolt performs an existential act aiming to reclaim the uninhibited, free body from the regime and its cognitive hold. The revolution's signature slogan, ‘the people want to topple the regime’, might very well have meant the people's desire to topple the oppressive ‘spectacle’ long imposed by that regime.

This ultimately means that the revolution can be discussed as a creative text in its own right, a text that lends itself to analysis via the tools of the trade of theatre and performance studies. Indeed, inasmuch as it is a social art dependent on presence in the ‘here and now’, theatre can offer unique insights into the operations of the revolutionary/performing body. This theatrical mode of knowledge, I propose, can be achieved in at least two strategic ways. First, by regarding the revolution as a battle between two distinct powers, each deploying its own discursive and cognitive weaponry. In other words, the revolution, qua conflict of wills, can be analysed as an event with discernible dramatic dimensions. Second, by viewing the revolution which took place at a specific time and place as a theatrical event capable of transforming mundane bodies into creative ones, while also reconfiguring place into a theatrical space and thereby subverting oppressive state power.Footnote 4 Precisely how all the above liberationist/theatrical energies apply to the Egyptian revolution is the core of the argument that I wish to make in this article.

The memory of place: Tahrir Square as text

Place is the principal text in which power establishes its presence by means of restructuring place's memory and manipulating its historical and cultural associations to serve its own interests. In order to identify this presence of power in Tahrir, we must first unpack the square's contents. A product of historic urban planning, the architecture of Tahrir can indeed help us understand the story of the city and its cultural practices, and, in the process, reveal the invisible power relations permeating every corner of it.Footnote 5

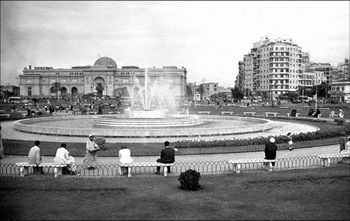

Shaped as a circle of two kilometres in diameter, the square now known as Tahrir (‘Liberation’) came into existence in the nineteenth century as part of Khedive Ismail's project to remake Cairo in the image of Paris. It was, therefore, initially known as Ismailia Square after the ruler who first conceptualized it. But while its architecture remained decidedly Western, intended to be reminiscent of the Champs-Elysées in the French capital, the overall design of the square in relation to the adjacent streets remained more reminiscent of souk, or the marketplace which functions as the centre in traditional Arab cities. The fourteen streets which branch out of Tahrir Square into the city and lead back to it thus establish it as a central spot, not unlike an octopus in shape. As such, Tahrir Square reflects in its design a more conservative ‘centripetal’ view of the world, suggesting as it does a fountainhead to which everything must inevitably lead back. This design has made the square an important spot that derives much of its traction from a number of symbolic centralities. These can be briefly highlighted as follows.

Geographical centrality

With many streets leading into and out of it, Tahrir Square represents the centre of the Egyptian capital. Octagonal in shape, it is bounded on one side by Abdul-Munim Riad Square, named after the Egyptian chief of staff who in March 1969 became one of the highest-profile ‘martyrs’ in the war of attrition against Israel (which, in turn, offered an outlet of sorts for national pride after the Zionist state's humiliating capture of Sinai in the Six-Day War of 1967). It was in that square that the historic funeral of President Gamal Abdel-Nasser took place in 1970. Four streets lead into Abdul-Munim Riad on the eastern side, including Champollion Street, named after Jean-François Champollion, the father of Egyptology who deciphered hieroglyphics through the Rosetta Stone, and Tal'at Harb Street, named after the father of the modern Egyptian economy. On its southern side lies Omar Makram Mosque, named after one of the leaders of the resistance against the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt in the nineteenth century. Beyond the mosque we find both the US and the British embassies, with their heavy security detail and inevitable trappings of neocolonial hegemony. Next to the mosque and the embassies stands Tahrir Complex (Mugamma Al-Tahrir), a centralized all-in-one administrative building that represents one of the fortresses of political power and is a centre of its proverbial bureaucracy.Footnote 6

Political centrality

In addition to Tahrir Complex, the square is also surrounded by the Cabinet headquarters and the two houses of the People's Assembly, or the Egyptian parliament. Before the 1952 revolution, the main barracks of the British troops were situated where the Nile Hilton Hotel now stands. The square was also the scene of major political events, including the Cairo Fire in 1952, the celebrations of the October War victory, and the 1977 ‘bread riots’, which erupted in protest against the austerity measures imposed by President Sadat and the subsequent rise in food prices.

Historical centrality

It should be evident from the above that Tahrir Square serves as a historical fair in more ways than one. In evidence at the square are practically all the historical ingredients and influences shaping Egyptian civilization: the Egyptian Museum represents the pharaonic civilization; the League of Arab States building represents Arabic civilization; the Omar Makram Mosque stands for Islamic civilization; Mugamma Al-Tahrir embodies the concept of the modern state and its bureaucratic apparatus; while the old campus of the American University in Cairo serves as a reminder, for good or worse, of the historic cultural influences of the West.

Such diverse centralities reflected in the architectural composition of Tahrir Square render the place a register of the many cultures that shaped and continue to shape Egyptian cultural identity. They also show, in their very diversity, that Egyptians exist in a context of cultural multiplicity and within a multiple time scheme where, again for good or ill, different ages and cultural undercurrents appear to coexist side by side.

Cultural centrality

As a fair of sorts, then, Tahrir Square represents both a cultural crucible and beacon. Over the years, the square has become the site of many an important ‘dramatic’ event with deeper implications for the life of the nation.Footnote 7 All these cultural dimensions of the square appeared to be lost on the post-monarchic state, which failed to imagine a cultural policy that would invest the square with contemporary meaning keeping pace with the changing zeitgeist. The state appeared content to dominate this space merely in political terms (as I will explain in a moment). Consequently, the square has remained ever since geographically divided amongst several cultures that all hark back to one form of the past or another, and which the 25 January revolution has had, perforce, to negotiate.

Fig. 1 A picture of Tahrir Square dated c.1940, also showing the Egyptian Museum. Source: Wikimedia.

Linguistic centrism versus the free presence of the body

The scene in Tahrir Square during the 25 January revolution soon assumed the character of a celebration, or rather a carnival that refuted the dominant cognitive hierarchies. This is partly thanks to this scene being a furja, the Arabic word for ‘spectacle’ which is derived in turn from the root faraj, meaning ‘the dispelling of sorrow or grief’.Footnote 8 The revolution can thus be said to partake of the Arabic root word for ‘spectacle’, inasmuch as it aimed to offer relief from the distress and affliction imposed by a long-existing ‘logocentric’ regime. This point calls for some further historical perspective.

Since the early years of the republican era, marked by the abolition of the monarchy as a consequence of the 23 July 1952 ‘revolution’ and the ultimate end of the British occupation following the 1956 Suez War, the nascent Egyptian state has attempted to establish its hegemony through a centralized linguistic presence predicated on ideals of national independence and pan-Arab socialism, much in accordance with the liberationist energies reshaping the world scene at the time. The result was a new set of power relations created at the level of official language but without much actual correspondence to existing social realities. It was, in short, a state that existed, as it were, as an entity projected from on high upon the structure of society.

In fact, for all the requisite veneer of modernity in line with the spirit of the times, traditional culture and its view of reality remained practically intact. This is because, curiously, the discursive practices of the 1960s state refrained from intervening in the private lives of individual subjects. These lives, in turn, remained predominantly governed by religion and other legacy aspects of the socio-moral order. Such a state of affairs ultimately resulted in a tacit coexistence, even alliance, between the national and the theological. Just as theology claims to descend from Heaven to offer answers to almost everything, the post-1952 state sought to establish itself as a superstructure intent on redrawing all social relations in its own image. It reproduced itself as a transcendental linguistic/cognitive centre, thus marginalizing or excluding all those aiming to pronounce on the truth differently. Respecting this status quo soon became a precondition for any ‘free’ expression to happen, inasmuch as one needed to rehearse its built-in language and protocols, which forbade the discussion of political or cultural issues in any alternative terms.Footnote 9

It did not help that from the 1970s onwards, as a result of profound social changes and the influx of alien, conservative values and ways of living from oil-rich Arab Gulf states, the body, already banished from the arena of social action by a totalitarian political system, was further denied visibility on newfangled moral grounds. As the locus of this new morality, the body was constrained and veiled, becoming one ‘enshrouded’ in ideology, a spectral being. Thus morality supported the day's political order in exacerbating the withdrawal of the individual within his/her body, and his/her exclusion from social action. The theologically sacred joined forces with the worldly sanctified to negate the efficacy of the aberrant body – the former, through accusations of heresy, accompanied by expulsion from the moral order, and the latter, through political repression, typically accompanied by physical torture.

Even worse, from that point in time and up until the 25 January revolution in 2011, the Egyptian state continued to lose whatever was left of its authority as a cognitive/linguistic centre. This soon resulted in a linguistic vacuum, a lack of grand nationalist causes or discourses capable of sustaining the ‘nation’ and bringing together all its disparate elements. Further, the state abandoned its former socialism of Nasserist times for an unapologetic free-market economy that characterized the two subsequent presidencies of Anwar Sadat (1970–81) and Hosni Mubarak (1981–2011). Throughout these eras, the state sought to cover the widening linguistic/discursive gap by further occasional resort to force, to its repressive apparatus as opposed its now ineffectual ideological apparatus.

It is important to recall here that each successive era of the post-1952 order had a distinct way of exercising its monopoly over meaning; all, however, remained intent on muzzling opposition in one way or another. As indicated earlier, the Egyptian state under Nasser sought to recruit all its subjects to the grand cause of its economic and social project, often silencing or imprisoning all those who opted to remain outside the official consensus. In a seeming departure from this non-pluralistic political setup, President Anwar Sadat allowed the forming of political parties, but such parties were practically denied the mobility to establish any real presence on the street in order to interact with the various rungs of society. This gradually resulted in a fake political pluralism, where one ruling party dominated all fields while the other parties merely served a cosmetic function. As for Mubarak's Egypt, the state tolerated criticism of the status quo only inasmuch it was confined to words and never translated into action. Political groups of all stripes became constrained, unable to effect any change, while language became the people's only means of venting their frustrations and suppressed desires.

All the while, thanks to the aggressive shift to capitalism, power further inscribed itself on the body thanks to the new fetish for consumption: the body became a consumer/object.Footnote 10 By the time Mubarak came to power, the absence of a unifying linguistic centre described above had transformed the individual into an isolated ‘I’, and the dominant language in society became that of self-absorbed bodies, a language of a random mass of socially ineffectual individuals. Such bodies possessed neither a sense of belonging to their place nor a self-assertive language that could allow them to engage meaningfully with other languages and cultures.

In short, during the post-1952 republic, the political and moral orders applied various means to deprive the body of its freedom of action and to curtail its presence in the social sphere. Reality for the individual became that of his/her mere body, not that of society. This eventually went hand in hand with the demise of language and of the creative, existential act. The living, potentially rebelling body appeared to be no more.

The real versus the unreal

In The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord has argued that media-dominated modern societies live on a collection of images, which are replaced by others every instant, so that the world becomes a mere image and our experience neither conforms to its reality nor is identical with it.Footnote 11 On the basis of this idea one can propose that revolutions erupt when the people realize that their existence is conditioned, controlled and defined by a collection of images manufactured and produced by a cognitive discourse that dominates through power relations. In this light, we can perceive what happened in Egypt on 25 January as a life-spectacle performed by a people to exchange one image of their world with a different one, or as a revolt against the spectacle conceded by the state's ideological apparatus.

It is now common knowledge that much of the initial impetus for the Egyptian revolution originated in the virtual world. Wael Ghoneim, a Google executive who became one of the Egyptian revolution's most internationally known poster boys, is reported to have said on several occasions that all he needed to do to advocate the revolution was to sit in front of his keyboard. This granted, how can we account for the success of the virtual in producing something as ‘real’ as the Egyptian groundswell revolution? The answer lies in the fact that the events of 25 January revealed a conflict between two cognitive systems: one claimed to be real while its age-old practices rendered it unreal in a number of ways (as argued throughout this article); the other, though virtual, advocated values and an alternative spectacle that individuals had long been craving in their reality. In other words, when the system excluded the body from reality, electronic social media provided the individual with an alternative cultural space in which to live and create a new language derived from this new technology, thereby making up for what had long been out of joint.

While the revolution in technology gave Egyptian dissidents the power to reject the past and its outdated values, global cyberspace also allowed them to keep abreast of what was happening in the world around them and to form alternative political ideas about liberty, social justice and different ways of living. The result was a deep crack that soon fractured the reality of the regime, revealing it to be a form of ‘hyper-reality’,Footnote 12 to apply Baudrillard's term, and giving the lie to its pseudo-metaphysical/patriarchal claims to safeguard and foster stability.

For its part, in its desperate effort to break the will of the revolution, the state sought to make its presence felt by deploying its security forces, its ultimate frame of reference. In thus parading its might, the regime was seeking to convince its subjects of the reality of its social system, one that had long relied for its existence both on the security dimension and, more patriarchally still, on the centrality of the economic system on which people's lives depended. A crisis discourse was deployed to frighten the people with the dire consequences of the collapse of the patriarchal system. Any disruption of the stability of the established system would endanger the economy and the security of the people, the state's propaganda machine barked day and night.

As a way of countering this discourse, the revolutionaries resorted to playing with signs, treating Tahrir Square as a symbolic resistance text capable of dismantling the logocentric practices of the regime. What follows are some non-exhaustive examples of this resistance.

Deconstructing the centrality of language

Mubarak's speeches during the revolution were overlong and tedious. They mainly relied on old rhetorical devices that invoked paternalistic values, while reminding the Tahrir angry children of the old Patriarch's glorious services as a veteran of the 1973 October War.Footnote 13 By contrast, the slogans adopted by the revolutionaries were brief and to the point, as if exposing the outdatedness and inadequacy of the regime's rigid governmentalities. Traditional frames of reference, with religion at the forefront (as I will elaborate in a moment), were all eschewed for the moment. Instead, the revolutionaries responded to the turns of the unfolding conflict instant by instant, devising and chanting slogans that consisted of short phrases akin to mobile text messages. In addition to the now iconic slogan ‘The people want to topple the regime’, other examples included ‘We shan't go, he will go’, ‘Depart means Buzz off! Got it?’ and many others that carried an equally sharp and irreverent humour, but which may lose much in translation.Footnote 14

Deconstructing the centrality of place

The regime dealt with Tahrir Square as simply one plot of land that had to be ‘liberated’ from aggressors/rebels. This view of Tahrir Square as an occupied territory to be liberated from insurrectionists within is curiously reminiscent of Foucault's panopticon metaphor, which allowed him to explore the relationship between systems of social control and people in a disciplinary situation in his Discipline and Punish. During the revolution, Tahrir Square, surrounded by official buildings representing power centres the members of which take turns guarding it, looked like a prison, and the revolutionaries became like the regime's prisoners. Naked, brute and irrational force was used to achieve the regime's aim of taking back control of the square, with the notorious ‘Battle of the Camel’ becoming a clear example of all such dynamics.

On Wednesday, 2 February 2011, at 2.00 p.m., agents of the embattled regime, in complicity with Egyptian security forces, tried to dissipate the protesters, with a little help from hordes of registered criminals. In what would become ever after a symbolic image indicating the difference between two mentalities, the assailants entered Tahrir Square on the backs of camels, holding swords and firing guns. Some of them climbed the buildings and started throwing Molotov cocktails on the protesters, causing many deaths and injuries.Footnote 15

Unlike this retrograde ‘camel-riding mentality’, the square, from the beginning of events until the toppling of the regime, was populated by bodies divested of the traditional theological and political standards and freely displaying more universal values, such as peace and equality. More precisely, the revolutionaries were guided in dealing with the place by the slogan demanding ‘Freedom, bread, and social justice’ for all. In so doing, the revolutionaries transformed Tahrir Square into a new sociocultural space where the traditional sign system inscribed on the city by the regime lent itself to deconstruction. Suddenly, Tahrir became a space where freedom and resistance to oppression could be practised without any of the received baggage.

Mass-mediated images of the camping protestors all confirmed a certain emerging utopianism. The square appeared as though it were free of any ideology, as if transformed (momentarily?) into an ideal society that had discarded all hierarchies and forms of discrimination based on class and religion – the very ills that had long been plaguing the Egyptian sociocultural sphere, which the square, in turn, had historically come to epitomize. It was as if a new reality had suddenly been ‘superimposed’ on an old one. Some of the mass-mediated photos showed Christians forming a circle around praying Muslim colleagues, thereby protecting them against any possible attacks by thugs or forces of the former regime. Other photos depicted Muslims joining their Christian fellows in prayer, or a Christian girl pouring water for a Muslim to do the ritual ablution before prayer. More intriguing still, some other images showed heavy bearded Salafis, the proponents of an ultra-zealous form of Islam, sitting peacefully and amicably with a group of singing ‘secular-looking’ fellow revolutionaries, a scene made all the more eyebrow-raising if one remembers the notorious Salafi prohibition against music and other forms of ‘wanton’ diversion. Images of the sort confirmed pluralism in the Tahrir community, where everybody had accepted the other's difference – or so at least it seemed at the time.

People in Tahrir Square came from all existing different backgrounds, but all shared the same target of toppling the regime. This may allow us to understand why the revolution has had neither an identifiable leader nor a central command dominating the operations of the square and strictly defining its demands. The ‘success’ of the revolution was the result of the disruption of all centrality of power and the subversion of many of the signs that marked the outdated sitting regime.Footnote 16

It would not be long before that this much-praised lack of centre would begin to reveal some self-defeating loopholes.

Fig. 2 A picture that went viral on the Internet and discussion groups, featuring prominent secularist activist George Ishak, a Coptic Christian who became one of the founding figures of the Kefaya opposition movement, standing guard on Qasr El-Nil Bridge to protect Muslim colleagues in the course of their Friday prayers. Significantly, the picture was taken in January 2012, during the anti-regime mass demonstrations that marked the first anniversary of the revolution.

Conclusion

The success of the 25 January revolution was built upon the urge to dismantle geographical, cultural, historical and political centralization. This dynamic highlighted the dramatic role of Tahrir Square, which soon became an exemplary stage where a number of global human values were played out.

But after toppling Mubarak and his regime in February 2011, the revolution appeared for a while to have rested on its laurels and to lose track of its original mission, thereby failing to reach out with its message to the wider context beyond its iconic Tahrir Square.

Tracing the causes and history of this failure, if that is the word, is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that the referendum on much-debated (Islamist-slanted?) constitutional changes held in Egypt on 19 March 2011 marked the beginning of the ever-widening division between Egyptians along various ideological and religious lines.Footnote 17 A heavily centralized political process, whether militaristic or Islamized or both, appeared to be ascending with a vengeance. Meanwhile, once the symbol of unity, Tahrir Square became a coveted war zone, both symbolic and actual. Each rival group sought to claim it as its own, along with the whole revolution for which it stood. Even worse, deadly violence erupted in the square and adjacent areas. Gone forever, perhaps, is the aspect of peacefulness that long kept the world in awe.

In the terms used throughout this essay, then, the revolutionary spectacle of the square has to date never been carried out in the rest of the city. The zeal to challenge any centralization gave way to the creation of new centralities in other parts of the city (such as Al-Ithadiyya Presidential Palace, Cairo University Square and Rabaa Al-Adawya Square). Each of these places was inhabited by one of the competing groups, claiming it as a launching pad for its message. The bodies in these competing squares are standard bodies which negate the space for any other, different bodies. The city space became marked by pockets of competing values and ideologies, most of them just as autocratic as those of the former regime.

This state of affairs, still far from conclusive at the time of this writing, leaves many to ask whether what happened in Tahrir Square was the birth of a new reality or an exceptional moment that can be neither sustained nor re-created. A new culture still needs to be fully imagined and practised beyond the authoritarian language and discourse that have long haunted the Egyptian public space. This, I believe, is the only way for the revolution to continue on its most meaningful path.