1. Introduction

Population ageing and the rise in multimorbidity are shifting the focus of health systems from responding to peoples' acute care needs to promoting prevention and efficient management of long term and chronic conditions (WHO, 2015). However, re-orientating health systems to meet the increasing complexity of population needs for care in combination with increasing financial and workforce pressures is a tremendous policy, managerial, and operational challenge. In response, health systems are targeting their efforts to deliver coordinated and integrated care, as it is expected to improve population health and patient experience while flattening healthcare spending (Gröne et al., Reference Gröne and Garcia-Barbero2001; Rocks et al., Reference Rocks, Berntson, Gil-Salmeron, Kadu, Ehrenberg, Stein and Tsiachristas2020). Integrated care can be defined as structured efforts to provide coordinated, pro-active, person-centred, multidisciplinary care by two or more well-communicating and collaborating care providers either within or across sectors (Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Struckmann, van Ginneken, Czypionka, Kraus, Reiss, Tsiachristas, Boland, de Bont, Bal, Busse and Rutten-van Molken2018). Countries have taken different approaches in implementing integrated care depending, among others, on their type of healthcare system (Leichsenring, Reference Leichsenring2004; Mur-Veeman et al., Reference Mur-Veeman, van Raak and Paulus2008). This is because financing and delivery models may predispose health systems to fragmentation to a greater or lesser extent and a customised approach of policies may be needed based on the specificities of each type of healthcare system. For example, delivering integrated care may be thought to be more challenging in a Bismarckian-like system with multiple payers and providers than in Beveridge-like system with a single-payer and provider. Still, even within a Beveridge-like system, the policies, delivery, and organisational model may vary in important characteristics that define different trajectories for health system fragmentation and elements of competition between service providers (Mur-Veeman et al., Reference Mur-Veeman, van Raak and Paulus2008). Therefore, experiences of countries with similar type of healthcare system that have made considerable progress in developing integrated care models, could potentially be followed by countries with the same type of healthcare system that are lagging behind in that regard. It is also important to trace back countries' progress in integrating care as setting the building blocks of integrated care is a long process (WHO, 2002).

Focusing on Beveridge-like health systems, we aimed to trace and compare the policies and reforms that have been implemented in England and Denmark in order to achieve higher levels of care integration. With this analysis we aimed to identify the domains of health care polices the two countries have focused on so far, with an objective to identify missed opportunities and lessons for future policy design in other countries facing the same challenges.

Both England and Denmark are Beveridge-like health systems where health care is financed through taxation and largely free at the point of use. Health care spending as a share of GDP has followed similar trends in the two countries and converged over time, with the UK going from around spending 7% of GDP in 2000 to 9.9 in 2019 while Denmark went from spending 8% in 2000 to 10.1 in 2020. In addition, the demographic challenge of an aging population is similar in both countries. In 2017/18, 31% of the Danish population and 38% of the UK population reported living with at least one chronic condition (OECD, 2022). Both countries are ranked on Toth's health integration index as highly integrated systems among OECD countries, in terms of: (1) integration of insurer and provider, (2) integration of primary and secondary care, (3) presence of gatekeeping mechanisms, (4) patient's freedom of choice, and (5) solo or group practice of general practitioners (Toth, Reference Toth2020). The policy efforts in these countries have similarities (e.g. the emphasis in both countries on introducing choice and competition at the beginning of the 2000s) but also differences (e.g. in the organisational setup), which provide a range of policies and reforms to inspire other countries with similar healthcare systems. The main focus of our analysis is care integration within the health care system (i.e. hospitals, primary and long term care) but this is closely related to other welfare services including social care and elder care, particularly for elderly with multimorbidity or people with disabilities and chronic care needs. Therefore, we also comment on integration policies across the social and elder care sectors where appropriate.

2. Methods

2.1 Data

Our analysis is based on desk research and analysis of policy documents describing new policies and reform with implications for integrated care in England and Denmark. The documents were identified based on the authors' knowledge of these policies and keyword searches in websites of relevant health authorities.

2.2 Comparative framework

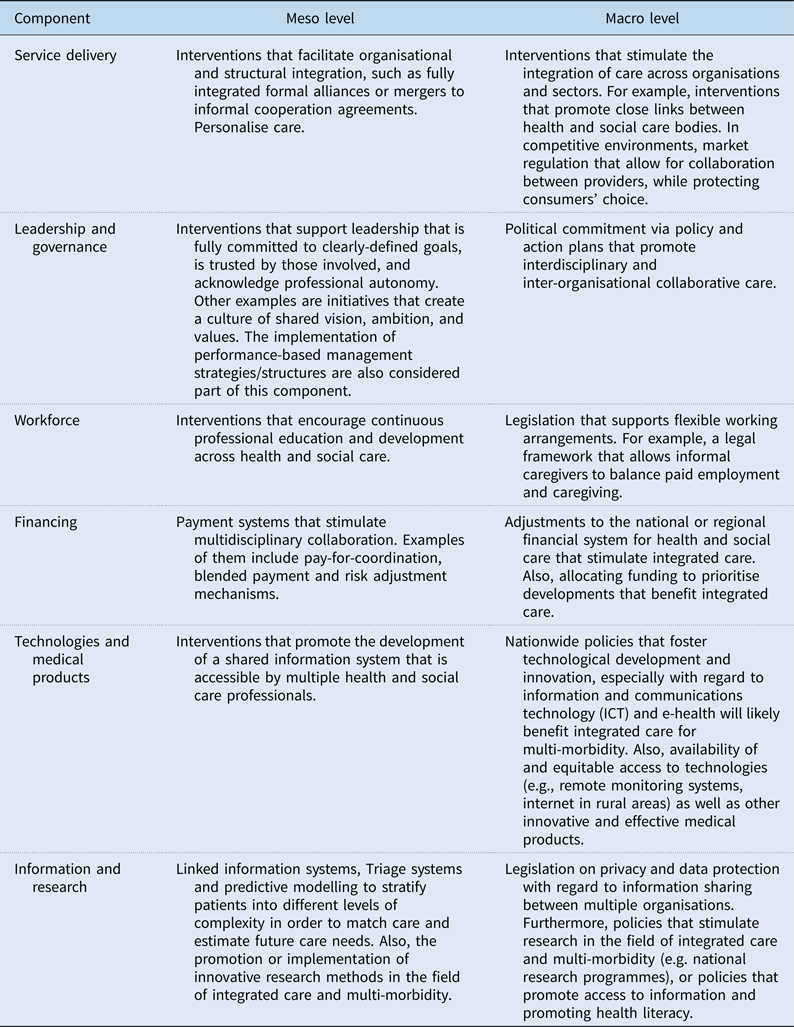

We used the SELFIEFootnote 1 framework to analyse and compare the factors facilitating and restraining integrated care in England and Denmark (Table 1). The SELFIE framework builds on WHO components of health systems, and provides insights for the development, organisation, and evaluation of integrated care for multi-morbidity (Leijten et al., Reference Leijten, Struckmann, van Ginneken, Czypionka, Kraus, Reiss, Tsiachristas, Boland, de Bont, Bal, Busse and Rutten-van Molken2018). This conceptual framework places the person at the core, and around it, structures relevant concepts in integrated care grouped into six components/domains: service delivery, leadership and governance, workforce, financing, technologies and medical products, and information and research. It was chosen for this analysis due to its comprehensiveness which facilitates a detailed analysis of the implications of new policies for integration at the macro, meso, and micro level (examples policies that affect integration at meso and macro level are presented in Appendix 1). While the policies of interest in this paper are predominantly at the macro level, most of them have implications at the meso level as well. Therefore, we have included these implications in our analysis, when relevant. We do not consider micro-level implications in this paper.

Table 1. Components of the SELFIE framework

Source: Adapted from Leijten et al. (Reference Leijten, Struckmann, van Ginneken, Czypionka, Kraus, Reiss, Tsiachristas, Boland, de Bont, Bal, Busse and Rutten-van Molken2018).

3. Results

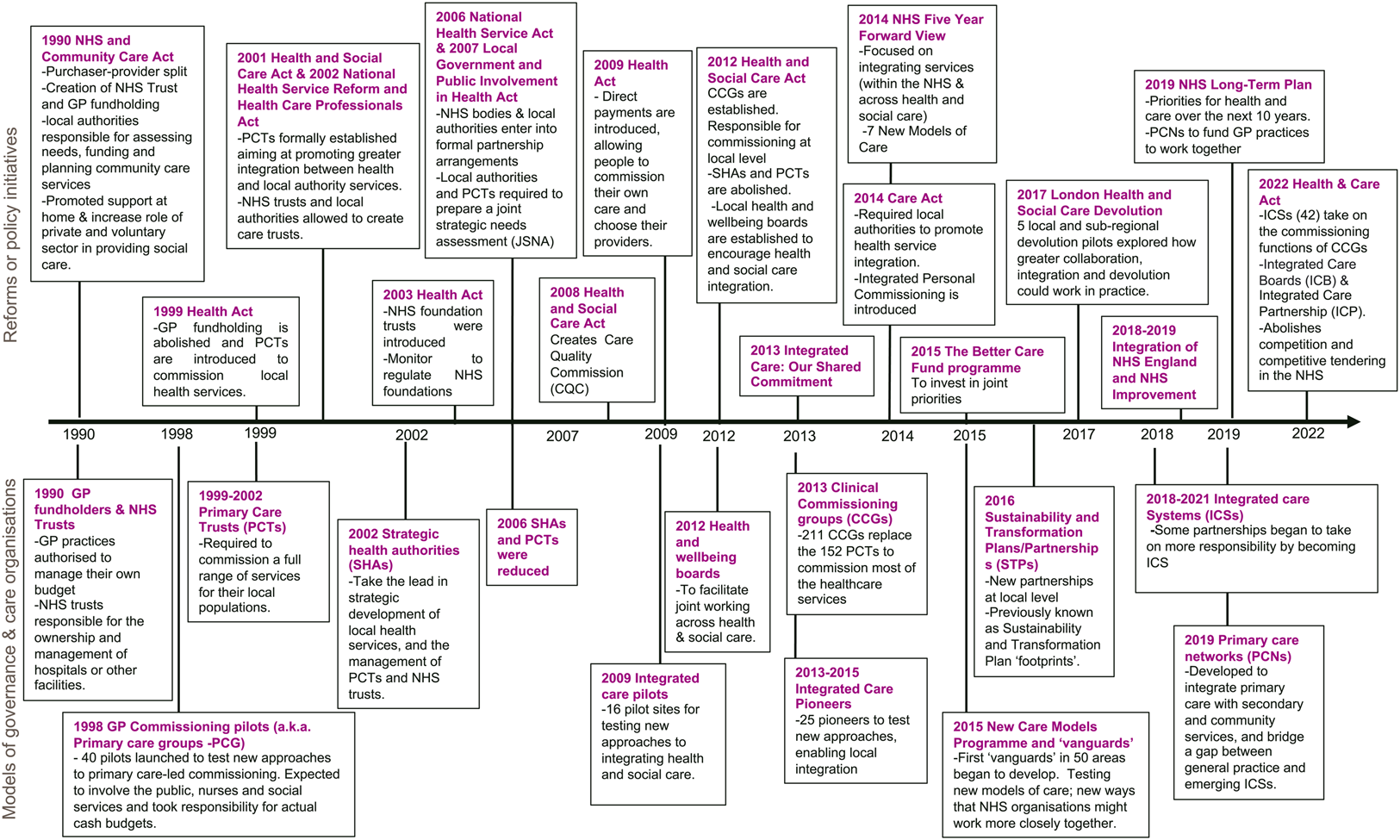

3.1 The English experience

The timeline of policy reforms that were related directly or indirectly to integrated care in England is presented in Figure 1. The top half of the figure shows the acts and policy initiatives while, the bottom half displays the evolution of governance and care organisation. Each of these policy reforms and emerged models of care and their relation to integrated care are described in the subsequent sections.

Figure 1. Timeline of English policies and models of governance and care related to integration of care.

3.1.1 1990–2000

During this decade, integration was encouraged and the foundations of creating organisations accountable to organise and deliver care to a population were set. However, it seems that the concurrently implemented policies towards a market-based healthcare system in the same period were counterproductive in stimulating integration of services (Greener et al., Reference Greener, Harrington, Hunter, Mannion and Powell2014; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Glasby and Dickinson2021).

The 1990 NHS and Community Care Act introduced a range of changes in the governance and delivery of health services in England (bold refers to components from the SELFIE framework. Underlined text refers to specific legislation) (UK Government, 1990; Nuffield Trust, 2020). In terms of organisational and structural changes, this act formally lay the foundations of the internal market within the NHS with the introduction of the purchaser-provider split (Glasby et al., Reference Glasby, Dickinson and Miller2011). The commissioners or purchasers (i.e. health authorities mainly) were handed budgets to purchase services from health and social care providers (UK Government, 1990; Nuffield Trust, 2020). This was coupled with the creation of NHS Trusts, responsible for the ownership and management of hospitals or other facilities, which were previously managed by regional, district or special health authorities. These ‘self-governing’ bodies were allowed to borrow money and make revenue directly from the provision of services (The Health Foundation, 2020).

To advance on the idea of a primary care-led NHS, outlined in 1990 NHS and Community Care Act, in 1997 the government announced plans to pilot new approaches to the commissioning of health services (The Health Foundation, 2020). These were possibly the first pilots exploring new forms of integration in the NHS. Forty GPs commissioning pilots, labelled as primary care groups (PCG), were launched in 1998. Each pilot group was responsible for an actual cash-limited prescribing budget, and were encouraged to involve the public, nurses, and social care workers. In addition to commission primary care services, these PCGs were also responsible for commissioning actual hospital and community health services budgets, and elements of general medical services budgets (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Regen, Shapiro and Baines2000).

From the service delivery, leadership and governance perspective, the 1999 Health Act established primary care trusts (PCTs) to take on the local commissioning functions undertaken by health authorities and GP fundholders (UK Government, 1999). The existing PCGs pilots evolved into PCTs as well. These new structures, with population coverage of 165,000, were also allowed to directly provide some services to their local populations and were accountable to the local health authority, although subject to directions from the Secretary of State (The Health Foundation, 2020).

To encourage coordination between health and social care, the 1999 Act allowed the NHS and local authorities to integrate health and social service staff into a single organisation and delegate commissioning to a single lead organisation (Glendinning et al., Reference Glendinning, Hudson, Hardy, Young, Glasby and Peck2002). In terms of financing, it was possible for PCTs and local authorities to pool budgets, and the Secretary of State was allowed to increase initial allocations if PCTs met certain objectives. The latter aimed at rewarding PCTs that made the most progress in implementing plans for improving healthcare (The Health Foundation, 2020).

3.1.2 2000–2010

Between 2000 and 2010, the government introduced multiple reforms that put in place a performance management system with more central control and incentivised ‘local dynamic’ mechanisms (Greener et al., Reference Greener, Harrington, Hunter, Mannion and Powell2014). The latter, aiming at promoting integration within the NHS and between health and social care (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Pitchforth, Edwards, Alderwick, McGuire and Mossialos2022).

In terms of service delivery, the Health and Social Care Act 2001 allowed NHS trusts and local authorities to create Care Trusts responsible for planning and delivering integrated services, covering health and community care (UK Government, 2001; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Glasby and Dickinson2021). Care Trusts became the first model close to a full merger of health and social care in the country (Glasby et al., Reference Glasby, Dickinson and Miller2011). To support this financially, the 2001 Act enabled the Secretary of State to increase financial allocations to Health Authorities or PCTs that achieved certain objectives and performed well against performance criteria (UK Government, 2001; The Health Foundation, 2020). This was coupled with substantial increases in health and social care funding between 2000 and 2007 (Glasby et al., Reference Glasby, Dickinson and Miller2011). In terms of leadership and governance, additional ‘command-and-control elements’ were introduced, by providing the Secretary of State with the power to intervene in an NHS body that was not performing adequately. On the same year, the National Care Standards Commission (NCSC) was established to regulate health and social care services, and promote the improvement of quality of services (The Health Foundation, 2020).

The National Health Service Reform and Health Care Professions Act 2002, abolished health authorities and created strategic health authorities (SHAs) (UK Government, 2002). The SHAs were larger authorities, covering 1.2–2.7 million people, responsible for managing performance, enacting directives and implementing health policies in their corresponding area. It included ensuring the delivery of improvements in health and health services locally by PCTs and NHS Trusts (Nuffield Trust, 2020). With the SHAs, a level of local discretion was allowed in regards of the different organisations would collaborate with each other (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Glasby and Dickinson2021).

A year after, a new act established NHS foundation trusts and a new regulatory body known as Monitor (UK Government, 2003). NHS Foundation trusts were introduced as a new form of NHS organisation with greater freedoms, including retention of surpluses, investing in the delivery of new services, and rewarding their staff flexibly (The Health Foundation, 2020). These elements stimulated innovation and efficiency through integrating services within NHS Foundation Trusts.

In 2006 and 2007, two new Acts consolidated most of the existing legislation related to the health service. Under this National Health Service Act 2006, NHS bodies (e.g. PCTs, Strategic Health Authorities) and local authorities were required to enter into formal partnership arrangements and to pool funds when necessary. In addition, the Secretary of State for Health was granted powers to designate PCT or NHS Trusts as Care Trusts, if he or she considered that such an arrangement would promote collaboration more effectively (UK Government, 2006). Aligned with this, the local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007 required the PCTs and local authorities to co-operate with one another and elaborate periodically a joint strategic needs assessment (JSNA) (UK Government, 2007) to identify relevant health and social care needs of their populations (The Health Foundation).

In 2009, new integrated care pilots were set up to test different approaches, including variations of case management, multidisciplinary team working, and the development of new organisational structures to promote integration of care (Ling et al., Reference Ling, Brereton, Conklin, Newbould and Roland2012; The Health Foundation, 2020). The focus was mainly on horizontal integration such as integration between general practices, community nursing services and social services (RAND Europe and Ernst&Young LLP 2012). Sixteen sites were appointed across the country, and were run for two years, targeting mainly elderly people with multiple co-morbidities. Despite the positive perceptions from the staff, the evaluation programme afterwards found no improvements in terms of patient experience or hospital utilisation in the short term (RAND Europe and Ernst&Young LLP 2012).

3.1.3 2010–2022

Although Integrated care was not originally a major part of the Coalition Government's plans for NHS reform, the Health and Social Care Act 2012 put in place an extensive governance and service delivery reorganisation, aimed at closer integration both within the NHS and across health and social care (Department of Health & Social Care, 2012; UK Government, 2012). Under this new regulation, PCTs and SHAs were abolished, and 211 Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) were established as groups of GPs that come together in each area to commission services for their patients and population. In terms of the financial arrangements, the 2012 Act made CCGs responsible to control the majority of the overall NHS budget (i.e. £60 billion and £80 billion), oversee local markets, and secure that health services were provided in an integrated way (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Pitchforth, Edwards, Alderwick, McGuire and Mossialos2022). In parallel, local leadership and governance were supported by the establishment of local Health and Wellbeing Boards, responsible for facilitating joint commissioning across health and social care organisations (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Glasby and Dickinson2021).

Between 2013 and 2014 a range of action plans and policy innovations were introduced to support integrated care (Briggs et al., Reference Briggs, Göpfert, Thorlby, Allwood, Alderwick, Adam and Briggs2020). A shared national vision of integrated care was embodied in the ‘Integrated care and support: our shared commitment’ framework document (National Collaboration for Integrated Care and Support, 2013; The Health Foundation, 2020). Local areas were invited to express interest in becoming health and social care integration pioneers, which were expected to work across health, social care and public health, as well as with local authorities and local voluntary organisations, sharing learning with the entire sector (Nuffield Trust, 2020). During this period, 25 pioneers were set up to test new approaches, enabling local integration. In 2014, a New Care act (UK Government, 2014) promoted integrated personal commissioning, legislating for the right to personal budgets. New standards on social care were set, carers were offered the right to receive support on a par with those they cared for, and local authorities were required to promote the integration of care with health services and ensure continuity of care where a provider ceases to provide a service (The Health Foundation, 2020). In line with this, local authorities were required to provide comprehensive information and advice about social care services in their local area (Department of Health and Social Care, 2016). In the same year, the NHS Five Year Forward view (2014 FYF) was published, setting up the challenges facing the NHS and how the delivery of health service needed to change, including a range of so-called ‘new models of care’ (NHS England, 2014). These new models of care advocate for the dissolution of the traditional boundaries across levels of care (i.e. primary care, community services, and hospitals) and call for a more personalised and coordinated provision of care to patients. With this policy document the notion of competition starts to debilitate, while the integration agenda is strongly emphasised.

To materialise the integration agenda defined by the 2014 FYF, 50 ‘vanguard’ sites were selected to implement the proposed ‘new models of care’ and a new fund was announced to benefit integration between health and social care (The Health Foundation, 2020). In 2015, ‘integrated primary and acute care systems’, ‘enhanced health in care homes’, ‘multi-specialty community providers’ were the first new models tested in 29 vanguards, followed by 8 additional vanguards, to improve coordination in relation to urgent and emergency care. Not much after, more radical approaches for the organisation of hospital care were implemented in 13 new vanguard (NHS England, 2016). These vanguards were one of the milestones for the development of new care models in England and the structural arrangements introduced by the government shortly afterwards (The Health Foundation, 2020). In terms of financing, the Better Care Fund (BCF) programme was launched, aiming to support local health and social care providers to work together and invest in joint priorities. In order to access the BCF money (£3.8 billion), CCGs, local authorities and health and wellbeing boards were required to work together to agree on a joint area plan (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Glasby and Dickinson2021).

To continue implementing the 2014 FYF, in December 2015 local authorities, CCGs and providers were asked to jointly create place-based Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs). These 5-years plans should outline the changes to be introduced to accelerate the implementation of the FYF (NHS England, 2015). A year after, 44 STP ‘footprints’ were submitted, reflecting the delivery plans of the different local health and care systems (The Health Foundation, 2020). Based on these ‘footprints’, England was divided into 44 areas for the NHS and local authorities to form Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs) to consider local health and care priorities and to plan services together. Although the STPs lacked legal standing, during these years multiple mergers between local hospitals, community health and mental health providers arose (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Glasby and Dickinson2021). Some of these STPs voluntarily evolved into Integrated Care Systems (ICSs), where commissioners and providers, often in partnership with local authorities, took collective responsibility for the health of their population and the required health (and in some cases social) care resources (The King's 2017; Wenzel and Robertson, Reference Wenzel and Robertson2019).

Following the review of the progress made since the launch of the 2014 FYF (NHS England, 2017), the NHS published its long-term plan in 2019, setting out the priorities for health and care over the following 10 years (NHS England, 2019). To move forward with the delivery of this plan, the government introduced significant reforms in 2022 via the 2022 Health and Care Act (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Gheera, Foster, Balogun and Conway2021; UK Government, 2022). Under this new regulation, CCGs were abolished and replaced by 42 statutory ICSs, formalising the way under which local partners within STPs or ICSs collaborate with each other (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021b). Within each ICS, Integrated Care Boards, health and social care providers, and the local authorities, who are responsible for commissioning social care services, are expected to work under a new statutory partnership to promote integration and deliver the best health and social care to their local populations (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021a). As was the case with the CCGs, Integrated Care Boards are able to commission jointly with local authorities (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021a). More pooled budgets and joint appointments across the two organisations are likely to emerge as a result of this transition (Gongora-Salazar et al., Reference Gongora-Salazar, Glogowska, Fitzpatrick, Perera and Tsiachristas2022). Along this, ‘provider collaboratives’ are emerging as partnership arrangements involving two or more NHS Trusts (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021c). The new Act also abolishes competition and competitive tendering within the NHS, reducing transaction costs and giving commissioners greater flexibility (The King's Fund, 2021). Integration between health and social care is also supported with a new standalone legal basis for the BCF, with the government committing with a minimum of £7.2 billion to the BCF in 2022 (Department of Health & Social Care, 2022a). In terms of the workforce, the act requires each ICB to promote education and training on learning disabilities and autism for health and social care provider staff. Concerning information, the act also allows the Secretary of State to require data from all adult social and health care providers including private providers (Department of Health and Social Care, 2022b).

3.2 The Danish experience

The Danish health system is based on three levels of democratic governance entities. The municipalities are responsible for a wide range of welfare state services Including social, elderly and home care services, local level prevention and rehabilitation. The middle layer is the regions, which are responsible for hospital care and for managing and paying for services delivered by private GPs and private specialist clinics. The national level includes the ministerial system and central agencies. In the following we present policy initiatives that have affected the ability to deliver integrated care, either indirectly (e.g. choice and digital infrastructure investments), or directly as an explicit aim of the policy. An overview of relevant policies and care models to integrated care in Denmark is presented in Figure 2 and described in the subsequent sections.

Figure 2. Timeline of Danish policies and models of governance and care related to integration of care.

3.2.1 1990–2000

Based on inspiration from reforms in Great Britain there was considerable debate about the potentials of market-based reforms in the late 1980s and early 1990s. – In the end, the Danish politicians opted for less radical market reforms that incorporated some elements of competition and economic incentives without radically changing the modus operandi. – This was based on a more consensual and pragmatic political style based on the Danish election system and parliamentary tradition with multiple political parties and frequent coalition governments, and a reluctance to experiment with solutions that could endanger the critical aim of maintaining expenditure control. Efficiency, cost containment, quality and waiting times were at the forefront of health policy debates during the decade, while integration gradually became a topic of concern as part of the quality debate. Other important development trends related to the creation of a digital infrastructure to facilitate communication and sharing of information across care levels.

Specific policy developments affecting service delivery and governance during the decade included the introduction of free choice of hospitals in 1993, which provided choice of public hospitals with the same level of specialisation upon referral. During the policy debates about this initiative concerns were raised that choice could negatively affect the linkages and communication channels between GPs (as family doctors) and hospitals if a substantial number of patients opted for treatment in other geographical areas. Therefore, restrictions in access to highly specialised departments were included in the law, and the economic incentives for receiving hospitals were limited. – Experience from subsequent years showed that relatively few patients exercised their right to travel to other hospitals, so the practical impact on integration was not substantial (Christiansen, Reference Christiansen2002; Vrangbæk et al., Reference Vrangbæk, Østergren, Birk and Winblad2007). Initially, payments for choice patients were based on fixed daily rates. This changed with the introduction of a Danish Diagnosis-related group (DRG) scheme in 1996. This scheme has subsequently been used for a number of financing and governance purposes including the calculation of block grants and various regional and national activity-based incentive schemes. Danish DRGs are based on ‘bundles’ of activities within organisations such as hospitals, but do not include activities across different care levels. The system therefore does not incentivise the integration of care across other organisational levels (Højgaard et al., Reference Højgaard, Kjellberg and Bech2018; Gjødsbøl et al., Reference Gjødsbøl, Langstrup, Høyer, Kayser and Vrangbæk2021).

Several policies were introduced to develop a digital infrastructure for communication and management during the 1990s. MedCom was established in 1994 as a non-profit organisation jointly owned by the Ministry of Health and the umbrella organisations for the regions (Danish Regions) and municipalities (Local Government Denmark). The role of MedCom is to facilitate and develop digital solutions across the Danish health care sector. It has been particularly important for developing standards for communication and thus serves as a basic infrastructure for integration of care.

An Action Plan for Electronic Health Records was presented by the Ministry of Health in 1996. Several counties acquired electronic health records in the following years. In 1999 this was followed by the publication of a national strategy for IT in the hospital system 2000–2002 by The Danish Health and Medicines Authority. This became the basic structure for electronic health records and set standards for formatting and compatibility (Gjødsbøl et al., Reference Gjødsbøl, Langstrup, Høyer, Kayser and Vrangbæk2021).

3.2.2 2000–2010

This decade saw several major new initiatives aimed to improve efficiency, quality, and integration in health care. The most important is a set of changes known as the ‘Structural Reform’. The political agreement about this reform was entered in 2005, and it was implemented in 2007. It implied changes in the governance structure, financing and distribution of responsibilities among the three political/administrative levels. All of these changes had implications for care integration. – At the structural level there was an amalgamation of municipalities into 98 new entities with an average of 30 K inhabitants. The aim was to strengthen the economic and professional capacity to provide integrated welfare services and to increase the role of municipalities in health care. The municipalities were given more responsibility for rehabilitation and health promotion, and there was an emphasis on developing synergy effects between social, elderly and health care at the municipal level. – The reform also meant that five new regions should replace the 13 counties as the responsible authority for managing and delivering specialised health care. The five regions were to develop integrated ‘hospital systems’ based on specialty planning and guidelines from the national level. Responsibility for managing and paying the private GPs and specialist clinics was also placed with the regions, based on the assumption that this governance and leadership structure could facilitate integration in service delivery (Christiansen and Vrangbæk, Reference Christiansen and Vrangbæk2018).

Two other major financing and governance changes were introduced with the ‘Structural Reform’ to strengthen integration of care across sector levels. The first was the municipal co-payment for hospital admissions and penalties for delayed discharge if municipalities were unable to provide follow up. The idea was to encourage municipalities to become better at providing services to prevent unnecessary hospital (re-)admissions and more generally to encourage both regions and municipalities to improve coordination specifically related to admission and discharge of patients.

The second was the establishment of ‘Health Coordination Committees’ where the regional councils, in cooperation with the municipal councils in the region, establish committees at political and administrative levels to coordinate regional and municipal health activities, to strengthen integration and avoid duplication of efforts. The political coordination committees were given the responsibility for entering formal (but not legally binding) agreements which were subject to approval by the national level authorities. The agreements specified workflows and communication requirements related to different patient groups and are thus a prime example of institutionalised policies to strengthen integration of care from a top–down institutional perspective. GPs were represented in the committees but due to their status as private enterprises they were not formal partners in the agreements (Rudkjøbing et al., Reference Rudkjøbing, Strandberg-Larsen, Vrangbaek, Andersen and Krasnik2014).

In the area of information systems a comprehensive IT strategy plan was launched in 2003 by The Ministry of Health. The aim was to integrate the many different digitalisation projects and to create a standardised approach to sharing EPR across different platforms (Indenrigs- og Sundhedsministeriet, 2003). One of the outcomes of the strategy was the development of ‘Sundhed.dk’, which is a portal for sharing patient information and communication between health professionals and patients. The portal has since been updated and the functionality has been extended several times, and it is now a comprehensive portal for sharing information, accessing guidelines and communicating about health related issues (Gjødsbøl et al., Reference Gjødsbøl, Langstrup, Høyer, Kayser and Vrangbæk2021).

Another important technology and information initiative was an agreement between the state and the Association of general practitioners from 2004 mandating that all GPs must use computer and digital record keeping systems in order to share clinical notes, etc (Gjødsbøl et al., Reference Gjødsbøl, Langstrup, Høyer, Kayser and Vrangbæk2021).

The efforts to implement the digital strategy were renewed with a joint regional agreement in 2010 to intensify the coordination of regional digitalisation efforts. The agreement involved 50 joint projects aimed at strengthening the regions' common direction, as well as strategy and efforts in relation to digitalisation, data, technology and innovation in the field of health.

Another important landmark in regard to technology and information was the implementation of a ‘Shared Medicine Card’ (Fælles Medicinkort) in 2010. This digital platform must be used by all parts of the health system, and it provides access for health professionals and citizens to information about the individual history of medicines and vaccinations (Gjødsbøl et al., Reference Gjødsbøl, Langstrup, Høyer, Kayser and Vrangbæk2021). It is therefore an important enabler of practical integration of care across institutional levels.

The policy ambitions of strengthening integration of service delivery and governance are also expressed in the introduction of Disease Management Programmes (Forløbsprogrammer). The Danish Health and Medicines Authority recommended the use of Disease Management Programmes for chronic diseases from 2005 in parallel to the implementation of the structural reform and its focus on strengthening integration of services, particularly for patients with chronic diseases. The ambitions to use Disease Management Programs as vehicles for better integration of care were further underlined in 2008, where the Danish Health and Medicines Authority created a generic model for such programmes. These were taken up by the five regions, which have since implemented Disease Management Programmes for various chronic diseases such as COPD, diabetes, and dementia. The Disease Management Programmes specify stratification criteria and recommended level of treatment along with guidelines for treatment practices (Vrangbæk, Reference Vrangbæk2023).

The emphasis on a stronger and more structured role of the municipalities for integrated service delivery was also expressed in the ‘Guidance for home health nurses’ from 2006. This policy document focuses on the role of municipal home health nurses in providing continuity, quality, and coherence in patient care, cf. VEJ no. 102

Despite these many efforts, there were persistent indications that truly integrated care remained an elusive target particularly for elderly patients and patients with multiple chronic and complex care needs. This was for example expressed in a report from the ‘The national audit office’ from 2009 showing that coherent patient pathways across the three sectors: general practice, hospital, and municipality should be improved (Folketinget Rigsrevisionen, 2009).

3.2.3 2010–2022

Following up on continued discussions about deficiencies in integration of care the ‘Economic Agreement’ for 2013 between the Government, the regions and the municipalities initiated analysis projects on the coherence between sectors. Topics included ‘an evaluation of the structural reform’, ‘analyzing structures and incentives in the health service’, and ‘the committee on potentials for improved municipal prevention’. The intention was to create a basis for initiatives to strengthen coherent patient care.

One of the outcomes was a recommendation to adjust the regional-municipal health agreements in order to make them less bureaucratic and more operational for health care organisations and professionals. The change in governance was implemented in 2015 and implied that the number of mandatory topics were reduced and that the number of health agreements decreased from one in each municipality to one in each region. The purpose was to strengthen health agreements and improve cross sector collaboration for coherent patient pathways. The agreement also allocated more funding for development of ‘patient centred health services’ (Regeringen og Danske Regioner, 2013).

A new ‘Danish Health Data Authority’ was created in 2015 to strengthen the coordination of digitalisation across sectors. This governance change signifies a perceived need for more central steering of digital developments in health care.

Another innovation in 2015 was the introduction of a ‘designated medical contact person’ for patients. The ambition was to ensure, that patients have a medical doctor to provide information and help navigate the system. The system was supposed to be fully implemented by 2019.

Several measures were taken in this decade to strengthen digitalisation at the municipal level. The introduction of ‘Common Language III’ in 2016–2020 aimed to provide joint standards for documentation and data generation in municipal health and elderly care. This was supposed to contribute to better coherence and better data in the municipalities' IT-based care records through the implementation of uniform concepts, classification and customised workflows (Gjødsbøl et al., Reference Gjødsbøl, Langstrup, Høyer, Kayser and Vrangbæk2021).

The national quality programme was re-designed in 2016 as a result of an agreement between the government, ‘Local Government Denmark’ and ‘Danish Regions’. The new programme consisted of three main elements (1) Eight national health care goals with associated indicators; (2) learning and quality teams in selected areas; and (3), a national programme for the development of leadership capacity. Goal 1 in this framework focused on integrated patient care and aimed to facilitate cooperation across different provider levels (hospitals, municipalities and general practice). The ambition was to provide a clear and common direction towards higher quality, and to make it easier to see where improvements were needed. Learning and quality teams were established across the regions and municipalities. The teams consisted of a network of relevant departments/units and an expert group with leading clinicians, experts in change management, data, etc (Indenrigs- og Sundhedsministeriet, 2023).

Another quality-oriented initiative for service delivery was the creation of ‘Quality clusters’ for GPs. The idea was to facilitate data driven quality discussions within groups of GPs including discussions about the integration of services with other care providers. The implementation of the quality model began on 1 January 2018, and over 50% of GPs are now in a cluster (Regionernes Lønnings- og takstnævn, 2017).

A ‘Cohesion Reform’ for the public sector was introduced in 2018. For health care this meant a change in the national financing of regions. A portion of the financing had previously been allocated according to activity-based criteria. This was now changed to ‘proximity health funding’, based on criteria that were seen as closely related to integration of care. The new criteria included: reduction in the number of hospital admissions overall, less in-hospital treatment for chronic care patients, fewer unnecessary readmissions within 30 days (based on the premise that stronger municipal care capabilities and better integration of municipal, GP and hospital care could reduce the need for hospital admissions), increased use of telemedicine and better integration of IT across sectors (Regeringen, 2018).

A new strategy for digital health 2018–2022 was published in 2018. It maintained the focus on the ability to share patient related information through standardisation and guidelines. The strategy included the reorganisation of the digital ‘Health Data Platform’ (Sundhed.DK) into a comprehensive portal for data sharing and communication. Work on this began in 2002 but it was subsequently expanded with new functions and reorganised to become the main digital entry point for health care professionals and patients. The system was also augmented by the ‘MyHealth’ app in 2019, which among others provided access to medical record data, laboratory results and an overview of health services in the vicinity. This app was instrumental during the COVID-19 pandemic as the entry point to test results, corona passports etc (Gjødsbøl et al., Reference Gjødsbøl, Langstrup, Høyer, Kayser and Vrangbæk2021).

A new governance initiative in 2021 was the introduction of 21 health clusters around each of the 21 major hospitals in Denmark. The purpose was to supplement the regional-municipal health agreements with a more practice driven and bottom-up approach to strengthen the integration services across hospitals, GPs, and municipalities in order to facilitate coherent patient journeys. This initiative was followed by a Health Reform Package in 2022. This reform package aimed to strengthen the quality of treatment by establishing new ‘health houses’ as locations for integration of care through co-location of health and care professionals from different institutional levels, strengthening the municipal capacity to deal with temporary and urgent health problems, and developing of municipal performance measures. It also contained a plan for securing better medical coverage in areas with a shortage of doctors, for example through the introduction of compulsory practice, etc. The latter illustrates how workforce shortages have increasingly become an issue of concern and an impediment to quality and care integration (Regeringen, 2022).

It should be noted that the previous presentation has focused on major national level initiatives, although often to be implemented at the regional and municipal levels. A number of bottom-up regional, municipal and local projects to facilitate integration of care have been introduced in parallel to the national initiatives throughout the period. – Either in response to national policies or as local/regional pilots that have subsequently influenced national decision making. In spite of these many national, regional and local initiatives the issue of integration remains salient in health policy debates in Denmark. This was most recently illustrated when the incoming coalition government established a high-level committee to prepare the introduction of a new and potentially comprehensive structural reform in 2024. Integration of care is a key issue in the guidelines for the work of the committee.

4. Discussion and lessons from looking across

In general, we found many similarities in the policies towards integrated care implemented in England and Denmark in the past thirty years. However, the use and dosage of different policy elements have differed from the outset, which in turn has put these two countries on somewhat different policy pathways. Interestingly, these policy elements are converging between the two countries in the latest sets of reforms in both countries. Figure 3 provides a summary of hard and soft policy initiatives towards integrated care in both countries by domain of the SEFLIE framework. As this figure shows, England appears to have had numerically more steps of policy reforms towards integrated care and the largest proportion was introduced in the last decade while in Denmark initiatives seem to have been more equally distributed in time. Furthermore, both countries have introduced reforms across all domains of the SELFIE model but it seems that most of these initiatives were targeting service delivery and leadership and governance while fewer policy initiatives specifically targeted technologies (in England) and information (both countries). The latter observation may be a reflection of the fact that data and digital technologies are considered integral prerequisites for governance and service delivery policies, at least in Denmark.

Figure 3. Domains of integrated care targeted by hard and soft policy initiatives in England and Denmark.

In the first half of the period under study, both countries introduced elements of market-based service delivery that enhanced patient choice of provider and strengthened competition between service providers. However, the implementation of these policies were more radical in England (e.g. with the purchaser-provider split). The Danish choice and competition reforms were more modest, partially due to a concern with the lack of coherence which could potentially result from patients seeking care outside their home geographical areas and partially due to a keen focus on maintaining budget control.

There has been a movement in policy approaches from competition to integration. This is partly due to ideological changes, but mainly due to the policy lessons these countries learned from the experimentation with competition in healthcare. In both countries, it was realised that competition had possibly hindered integration (competition failures).

While both countries saw large structural reforms in the mid-2000s that changed both the service delivery and governance landscape, the way the countries went about stimulating integration differed. England, which even after structural reforms is the more centralised of the two countries, opted for a pilot approach, where local areas could pursue new models of care in various formats, but on their own (local) initiative within a national framework. These new models primarily had the function of setting local areas free to form new organisational or governance structures and in that sense introduced decentral deviations from an otherwise centralised system.

Denmark, on the other hand, retained a decentralised service delivery and governance structure based on larger regions and municipalities after the Structural reform in 2007, but at the same time introduced national policies to stimulate integration through financial incentives, for example, the municipal co-financing of hospital care, and much later the ‘proximity health funding’, i.e. centralising elements in a decentralised system. Although the size and effectiveness of the incentives have been subject to debate, it is noteworthy that Denmark, in this area, chose to combine structural delivery and governance policies (larger units and mandatory health agreements between regions and municipalities) with financial incentives to a greater extent than England, because that deviates from the approach to for example stimulating the provision of high quality of care, where England has been relying more on financial incentives for quality in both primary and secondary, while pay for performance has been largely absent in the Danish health care sector. In doing so, each country has, in its own way, tried to reshape the incentives created by activity-based payment schemes such as DRG and fee for service, which do not stimulate coherent care across sectors.

There is an increasing frequency of policy initiatives and a tendency to formalise integration initiatives over time in both countries. Integration was always an issue. But as the volume and pace was lower, much could be managed informally through mutual adjustments and customised local solutions. In the past two decades, there have been a stronger tendency to enter formal agreements and negotiate standard patient pathways while adhering to national guidelines and disease management programs. Formal agreements are often supported by increasing demands for transparency/accountability in regard to performance.

After some deviation in the policy pathways, England and Denmark converge at the end of the period. There are clear parallels between the governance structure of the English Integrated Care Systems and the new health clusters introduced in Denmark in 2022. In England the ICSs are the result of a great deal of piloting and experimentation for about a decade, while in Denmark, the health clusters extend and formalise leadership and governance structures already in place since the structural reform in the form of Health agreements.

One notable difference between the two countries is the English tradition of setting clear national targets when announcing new policies. For example, with the establishment of the BCF, all local areas were required to set out clear ambitions for acute admissions, the effectiveness of reablement and delayed transfers of care days. For example, for 2020, the combined ambition was to have 106,000 fewer acute admissions, and 293,000 fewer delayed discharges. On the contrary, the Danish policy initiatives are rarely accompanied by clear statements of expected results. There may be references to the eight overall goals for the health care system, but the policy documents are often vague in terms of specific goals, with more emphasis on justifying the need for action. This is likely related to the more decentralised approach to governance the health care sector in Denmark, where new initiatives in the health system are most often the result of agreements between the regional/municipal actors and the government and there is an emphasis on regional/local involvement in the definition of goals.

While the clear goals set in the UK in theory would make collective action more focused, it is rare that these goals have actually been achieved – at least in the short run – and it is therefore not clear whether a more decentralised approach to policy making is more successful in generating change – of course the lack of clearly stated goals often seen in Denmark at the same time makes it harder to evaluate whether a certain initiative was successful or not.

The lack of convincing effects of previous initiatives also raises the question of whether the latest policy interventions are likely to be effective, in particular whether greater integration can and will generate the desired effects. In both countries, the emphasis on integrated care comes on a backdrop of pressure on the health system driven by an ageing population and increasing financing and workforce pressures. To be successful, reforms should therefore alleviate this pressure, either by reducing the demand for care, or shifting care to less resource intensive settings.

Information systems and in digitalisation is important as a tool for improved communication and sharing of information. However, it has not solved all coordination issues, and it takes more than just digital tools to provide true integration of care. Digitalisation also creates new workflows and tasks.

Organisational and professional cultures matter as they provide guidance in situations of uncertainty. It is important to create cultures that support the investment of time and resources in aligning efforts across organisational boundaries. Organisational incentives should support this, but so far there are few examples of value/performance payment based on integrated care.

Taken together, reforms in both countries have focused on service delivery, leadership and governance, and financial incentives. The role of information, technologies and medical products is only beginning to be explored and it is likely that we will see more innovation in the use of new technologies such as artificial intelligence and home monitoring to weave the health system together in the future. Such technological developments would surely be welcome in both countries as the challenges of maintaining a sufficient workforce is beginning to emerge.

5. Conclusions

The experience of England and Denmark in reforming their healthcare systems to achieve integration of care suggest that (a) collaboration is a more fostering environment for integrated care than competition, (b) service organisation should be decentralised to local ‘ecosystems’ that are large enough to create innovation, synergies, and economies of scale while reducing bureaucracy, (c) financial incentives should be in place to facilitate collaboration and co-production of high quality care, (d) flexible workforce with multidisciplinary culture is essential, (e) bold steps in modernising health informatics and boosting digitalisation should be taken early on rather than at the end of the reform journey. These could become lessons for other countries with Beveridge-like health systems to transform toward integrated care without having to ‘re-invent the circle’. How the evolution of integrated care takes place in Bismarck type health systems and how that differs from our findings is yet to be investigated.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133123000166

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of the participants of the European Health Policy Group that took place on 27th and 28th June 2022 in London, United Kingdom.